Nathaniel Rochester: Difference between revisions

→Legacy: added citations |

|||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

===Legacy=== |

===Legacy=== |

||

[[Rochester Institute of Technology]] has a dormitory named Nathaniel Rochester Hall, the third tallest of the campus' four dormitory towers. Nathaniel Square Park, at the intersection of South Avenue and Alexander Street in the South Wedge neighborhood is home to a statue of Nathaniel Rochester sitting on a bench, sculpted by Pepsy Kettavong. There is also a school in the city of Rochester named Nathaniel Rochester Community School (School No. 3). |

[[Rochester Institute of Technology]] has a dormitory named Nathaniel Rochester Hall, the third tallest of the campus' four dormitory towers. Nathaniel Square Park, at the intersection of South Avenue and Alexander Street in the [[South Wedge Historic District|South Wedge]] neighborhood is home to a statue of Nathaniel Rochester sitting on a bench, sculpted by Pepsy Kettavong.<ref>https://rocwiki.org/Nathaniel_Square</ref> There is also a school in the city of Rochester named Nathaniel Rochester Community School (School No. 3).<ref>https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/schoolsearch/school_detail.asp?ID=362475003378</ref> |

||

===Slavery=== |

===Slavery=== |

||

Revision as of 15:05, 14 April 2022

Nathaniel Rochester | |

|---|---|

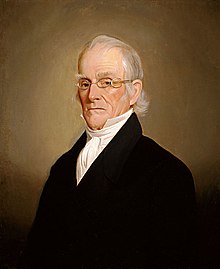

Portrait of Rochester by John Audubon, 1824 | |

| Member of the Maryland General Assembly | |

| Member of the North Carolina General Assembly | |

| In office 1777–1777 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 21, 1752 Westmoreland County, Virginia |

| Died | May 17, 1831 (aged 79) Rochester, New York |

| Resting place | Mount Hope Cemetery |

| Spouse |

Sophia Beatty (m. 1788) |

| Children | 12, including William, Thomas |

| Signature | |

Nathaniel Rochester (February 21, 1752 – May 17, 1831) was an American Revolutionary War soldier, and land speculator, most noted for founding the settlement which would become Rochester, New York.

Early life

Nathaniel Rochester was born to John and Hester Thrift Rochester in Westmoreland County, Virginia on February 21, 1752, the fifth of six children.[1] His father, who owned Rochester House,[2] died in 1756. Five years later Hester married Thomas Cricher, who moved the family to Granville County, North Carolina in 1763, where Nathaniel attended the school of the Reverend Henry Pattillo.[3]

At age 16, he found a job with a local Hillsborough merchant, signing a two-year contract paying ₤5 per year. At the end of six months, his contract was revised to pay him ₤20 per year and Rochester would became partner in the business within five years. In his early working years, Rochester also served as clerk for the vestry of St. Matthew's Parish, as a committee member for a civic organization, and, most notably, as a delegate to North Carolina's first Provincial Congress.

Career

Military, politics, and business

In 1775, as the Revolution approached, Rochester was named to the Committee of Safety for Orange County, wherein, according to Rochester, his duties necessitated him to "promote revolutionary spirit among the people, provide arms and ammunition, make collections for the people of Boston, and prevent the sale of East India teas." On 20 August of that year he attended the Third Provincial Congress as a representative of Hillsborough. Rochester was appointed a Major in the North Carolina militia and served as justice of the peace and paymaster of the battalion of minutemen in the district of Hillsborough. The following year, he was assigned command of two infantry and one cavalry company tasked with following Colonel James Thackston in pursuit of Tories marching to join the British at Wilmington. En route, his force captured five hundred Tories retreating from the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge.

In 1776 Rochester represented Orange County in the Fourth North Carolina Provincial Congress meeting at Halifax and was elevated to the rank of colonel in the North Carolina Line. Due to illness, however, Rochester was rendered unfit for military duty and had to resign his command. His role in politics was not affected, though, and in 1777 he was elected to the North Carolina General Assembly, where he served as county clerk. In addition, Rochester was appointed Colonel of the North Carolina militia, and Commissioner in charge of building and managing an arms factory in Hillsborough[4] as well as receiving commission to supervisor the building of a new courthouse[5] and to assist in establishing an academy in the Hillsborough area.

In 1778 Rochester resigned his positions and entered into a mercantile venture in partnership with Colonel Thomas Hart, a notable and wealthy merchant and land speculator, and James Brown. The business was successful and Rochester began to invest his earnings in real estate, a practice he continued throughout his life. With the British Army's occupation of Hillsborough imminent, Rochester moved to Philadelphia where he was almost immediately stricken with smallpox. After a lengthy convalescence he joined Hart in Hagerstown, Maryland where the two became partners in a flour mill, a nail and rope factory, a bank, and a farm.

Rochester remained in Maryland for thirty years, where he served one term in the Maryland General Assembly, and two years as postmaster. He was elected as a judge in 1797, but recognizing that he did not have the proper legal training, resigned the post. Rochester served as Washington County's Sheriff from 1804 to 1806,[6] a presidential elector, and vestryman of Saint John's Church.

In 1807, Rochester helped found the Hagerstown Bank, serving as its first president.

Land speculation

Two of the directors of the Hagerstown Bank, Colonel William Fitzhugh and Major Charles Carroll[7] were, like Rochester, wealthy landowners interested in acquiring land in the new "frontier" of the U.S. In 1800, Fitzhugh and Carroll convinced Rochester to travel with them on a prospecting visit to the frontier lands of New York State, and specifically to the lands along the the Genesee River. Their first trip took them to Dansville, where Rochester purchased a combined 520 acres while Fitzhugh and Carroll purchased another 12,000 at $2 per acre.[8]

In November, 1803, the three men returned to Western New York, this time to Geneva to make payments. Here, they were convinced by the land agent to visit the Genesee falls further north,[9] where they found an abandoned grist and saw mill—opened in 1789—once owned by Ebenezer “Indian” Allen. The men saw a business opportunity here as any products travelling up river toward Lake Ontario would need to be unloaded here and portage fees could be charged. On November 8, 1803, the three men signed a purchase agreement for a 100-acre (0.40 km2) tract of land near the river's Upper Falls. The final payment of $1,750 was made on June 22, 1808.[10]

Life on the Genesee

Rochester's interest in the land he now owned along the Genesee, in part, prompted him to decide to relocate his family to the river valley in May, 1810.[11] On 10 June of that year, the family reached Dansville and established a homestead.

Rochester quickly became a leading citizen of Dansville upon his arrival, establishing numerous businesses and mills and playing an active role in the early politics of the town. So busy was his life in Dansville that he offered to sell his share of the Upper Falls tract to Major Carroll, though Carroll convinced him to keep his interest. In January, 1814, Rochester sold his property and holdings in Dansville—a grist mill, saw mill, 700 acres of land, interest in a wool carding shop, and the first paper mill in Western New York—for $24,000 and moved to East Bloomfield in Ontario County.[12]

Rochesterville

In 1811, Rochester began the process of establishing a town on the Upper Falls tract. He laid out streets on a gridiron pattern and established plots of land for municipal, church, and business use. Later that year, he began to offer the plots for sale:[13] quarter-acre lots on the two main roads—Buffalo Street running east to west and leading to a bridge across the river, and Mill Street running north to south—were sold for $50, except for the northwest lot at Four Corners, which sold for $200; lots on adjoining streets were sold for $30 and buyers were required to pay a $5 deposit and build a home or business twenty-by-sixteen feet within one year in order to secure the lot. He reserved large lot on Buffalo Street for public buildings.[14] While the settlement had previously been called The Falls or Falls Town, the three partners agreed to the name "Rochesterville." When later accused of vanity for the name Rochester quipped, "Should I call [the village] Fitzhugh or Carroll, the slighted gentleman would certainly feel offended with the other; but if I called it by my own name, they would most likely be angry with me; so, it is best to call it Rochester and serve both alike."[15]

The first settlers to arrive, on May 1, 1812, were Hamlet Scrantom and his family. Work on their cabin at Four Corners was not yet finished so the family stayed with Rochester's land agent Enos Stone, who'd been living in Allen's former mill on the east side of the river, until its completion on July 4, 1812.[16] Next came Jehiel Barnard, arriving on September 1 and erecting the settlement's first tailor shop, which would also become its first meeting house and church.[17] Other initial settlers included Abelard Reynolds, who established a pioneer saddlery and the village's first post office, and whose son, Mortimer, is believed, in 1814, to be the first white child born in Rochester;[18] Silas O. Smith; Elisha and Hervey Eli; and Josiah Bissel, Jr.[19]

The War of 1812 helped Rochesterville grow as settlers living in Charlotte and other settlement along the shore of Lake Ontario sought to move farther inland. Furthermore, numerous skirmishes and war activities were taking place throughout western New York and Rochesterville served as a waypoint for troops heading west as well as a depot for military supplies. The exposure proved advantageous for the settlement, as many people who had travelled through purchased lots or tracts in or near the village. In fact, one lot, which sold for $200 in 1811, would eventually for $11,200 in January 1817.[20]

In 1817 Rochester served on a committee to petition the state to build what would become the Erie Canal on a proposed northern route that included a route across the Genesee River at Rochesterville. The eventual decision by the state's government to accept this northern route became a predominant factor in the growth of the future city. In late 1817, Rochester helped petition the state for the incorporation of Rochesterville. Although the first petition failed due to opposition from neighboring jurisdictions, a second petition passed and the City of Rochester was incorporated on 21 April. The suffix -ville was dropped in 1822. Also in 1817, Rochester was part of a group which organized St. Luke's Episcopal Church, Genesee Falls,[21] with Rochester serving as its first Senior Warden. Eventually Rochester gave land for the building of the church on Fitzhugh Street.

In 1821 Rochester played a pivotal role in the creation of Monroe County, which Rochester named after President James Monroe. When the county was officially formed, Rochester became its first county clerk and was elected as the county's first representative to the New York State Assembly.

Later years

Rochester remained an active participant in the growth of the town and county he founded, playing many pivotal roles in the development of its economy and status. He played an active role in politics, helped found churches and banks, and served as the first president of the Rochester Athenænum (which would later become Rochester Institute of Technology).

During the last two years of his life, Rochester made few public appearances, but rather spent most of his time with his now rather large family, including his 28 grandchildren still living at the Colonel's 79th birthday.

Suffering from a protracted and painful illness, Rochester died May 17, 1831. He was interred at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester.[22]

Personal life

In 1788, he married Sophia Beatty (1768–1845) in Hagerstown, Maryland, and they had twelve children,[23] among them Judge and Congressman William B. Rochester and Mayor Thomas H. Rochester.

Legacy

Rochester Institute of Technology has a dormitory named Nathaniel Rochester Hall, the third tallest of the campus' four dormitory towers. Nathaniel Square Park, at the intersection of South Avenue and Alexander Street in the South Wedge neighborhood is home to a statue of Nathaniel Rochester sitting on a bench, sculpted by Pepsy Kettavong.[24] There is also a school in the city of Rochester named Nathaniel Rochester Community School (School No. 3).[25]

Slavery

A 1790 account book, purchased from Rochester's descendants by the University of Rochester's Rush Rhees Library, uncovered Nathaniel Rochester's involvement in the slave trade. The ledger shows the purchase and subsequent sale of human beings by Rochester and his partners in that year, though it is unknown to what extent he participated in the slave trade in other years.

When Rochester, Fitzhugh, and Carroll made their initial journey to the Genesee Country in September 1800 there were accompanied by at least one slave; and when Rochester moved from Hagerstown to Dansville in 1810 he brought with him about half a dozen slaves.[26]

According to an 1811 document, Rochester did free two of his slaves. A document of manumission states: "... by those present doth manumit and make free from slavery my Negro Slave named Benjamin about sixteen years old and my Negro Slave Casandra about fourteen years old." Another document shows that, on the same day, another slave, Casandra was made an indentured servant who would learn to read and write and also "the art and mystery of a Cook," "until the said apprentice shall accomplish her full age of eighteen years."[27]

References

- ^ Rochester, Nathaniel (1924). A Brief Sketch of the Life of Nathaniel Rochester, Written by Himself for the Information of His Children. Rochester, NY: The Rochester Historical Society.

- ^ https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/096-0087/

- ^ https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/rochester-nathaniel

- ^ https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr13-0413

- ^ https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr13-0510

- ^ http://www.whilbr.org/Rochester/index.aspx

- ^ https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/finding-aids/D488

- ^ Osgood, Howard (1922). "Rochester; Its Founders and Its Founding". Publications of the Rochester Historical Society. 1: 57.

- ^ Osgood, Howard (1922). "Rochester; Its Founders and Its Founding". Publications of the Rochester Historical Society. 1: 59–60.

- ^ https://rochistory.wordpress.com/2017/03/21/so-it-is-best-to-call-it-rochester-how-the-community-came-to-be/

- ^ Barnes, Joseph; Heininger, Mary Lynn Stevens (1984). 4 Score & 4 Rochester Portraits 1984. Rochester, NY: Rochester Sesquicentennial Inc. p. 4.

- ^ Osgood, Howard (1922). "Rochester; Its Founders and Its Founding". Publications of the Rochester Historical Society. 1: 55.

- ^ https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn83031529/1811-09-03/ed-1/seq-3/#sequence=0&proxdistance=5&county=&phrasetext=&andtext=&date1=01%2F13%2F1700&city=&date2=11%2F31%2F2000&searchType=advanced&from_year=1700&proxtext=rochester&dateFilterType=range&sort=date&SearchType=prox5&index=1&to_year=2000&rows=20&words=Rochester&lccn=sn83031529&am+p=&ortext=&page=1

- ^ McKelvey, Blake (1993). Rochester on the Genesee The Growth of a City. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0815625960.

- ^ https://rochistory.wordpress.com/2017/03/21/so-it-is-best-to-call-it-rochester-how-the-community-came-to-be/

- ^ https://rochistory.wordpress.com/2017/04/18/rochesters-first-settler-hamlet-scrantom-1-december-1772-10-april-1850/

- ^ https://rochistory.wordpress.com/2017/04/04/whatever-needs-doing-jehiel-barnard-17-august-1788-7-november-1865/

- ^ Arnot, Raymond (1922). "Rochester; Backgrounds of Its History". Publications of the Rochester Historical Society. 1: 97.

- ^ McKelvey, Blake (1993). Rochester on the Genesee The Growth of a City (Second ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0815625960.

- ^ McKelvey, Blake (1993). Rochester on the Genesee The Growth of a City (Second ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0815625960.

- ^ https://rocwiki.org/St._Luke%27s_Church

- ^ Duffy, Bob. "State of the City 2009". Rochester, New York. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll9/id/3984

- ^ https://rocwiki.org/Nathaniel_Square

- ^ https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/schoolsearch/school_detail.asp?ID=362475003378

- ^ Osgood, Howard (1922). "Rochester; Its Founders and Founding". Publications of The Rochester Historical Society. 1: 56, 62.

- ^ https://www.rochestercitynewspaper.com/rochester/portrait-of-a-slave-trader/Content?oid=2128459

Sources

- McKelvey, Blake (January 1962). "Colonel Nathaniel Rochester" (PDF). Rochester History. XXIV (1). Rochester Public Library. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- Stokes, Durward (October 1961). "Nathaniel Rochester in North Carolina". The North Carolina Historical Review. XXXVIII (4): 467–481.

External links

- Nathaniel Rochester at Find a Grave

- North Carolina Historical Marker

- Sheriff Nathaniel Rochester's Records, Washington County, 1804-1806 Western Maryland Regional Library.

- Hagerstown Bank collection at the University of Maryland Libraries.

- Politicians from Rochester, New York

- Burials at Mount Hope Cemetery (Rochester)

- 1752 births

- 1831 deaths

- People from Hagerstown, Maryland

- Genesee River

- Members of the New York State Assembly

- 1816 United States presidential electors

- Military personnel from Rochester, New York

- Members of the North Carolina General Assembly

- Members of the Maryland General Assembly

- American slave owners

- Maryland postmasters

- People from Westmoreland County, Virginia

- People from Granville County, North Carolina