The Elephant Man (film): Difference between revisions

removed Category:English-language films; added Category:1980s English-language films using HotCat |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

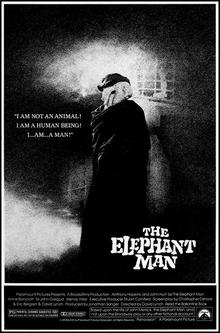

| caption = Theatrical release poster |

| caption = Theatrical release poster |

||

| director = [[David Lynch]] |

| director = [[David Lynch]] |

||

| producer = [[Jonathan Sanger]] |

| producer = {{unbulleted list|[[Jonathan Sanger]]|[[Mel Brooks]] (uncredited)}} |

||

| screenplay = {{unbulleted list|Christopher De Vore|[[Eric Bergren]]|David Lynch}} |

| screenplay = {{unbulleted list|Christopher De Vore|[[Eric Bergren]]|David Lynch}} |

||

| based_on = {{plainlist| |

| based_on = {{plainlist| |

||

Revision as of 14:56, 26 April 2022

| The Elephant Man | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Lynch |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Freddie Francis |

| Edited by | Anne V. Coates |

| Music by | John Morris |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million |

| Box office | $26 million (North America)[3] |

The Elephant Man is a 1980 British-American biographical drama film about Joseph Merrick, here called John Merrick, a severely deformed man in late 19th-century London. The film was directed by David Lynch and stars John Hurt, Anthony Hopkins, Anne Bancroft, John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Michael Elphick, Hannah Gordon, and Freddie Jones. It was produced by Mel Brooks, who was uncredited so audiences wouldn't see his name and expect a comedy, and Jonathan Sanger.

The screenplay was adapted by Lynch, Christopher De Vore, and Eric Bergren from Frederick Treves's The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923) and Ashley Montagu's The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity (1971). It was shot in black-and-white and featured make-up work by Christopher Tucker.

The Elephant Man was a critical and commercial success with eight Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor. After receiving widespread criticism for failing to honour the film's make-up effects, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was prompted to create the Academy Award for Best Makeup the following year. The film also won the BAFTA Awards for Best Film, Best Actor, and Best Production Design and was nominated for Golden Globe awards. It also won a French César Award for Best Foreign Film.

Plot

Frederick Treves, a surgeon at the London Hospital, finds John Merrick in a Victorian freak show in London's East End, where he is kept by Mr. Bytes, a greedy, sadistic, and violent ringmaster. His head is kept hooded, and his "owner", who views him as intellectually disabled, is paid by Treves to bring him to the hospital for examination. Treves presents Merrick to his colleagues and highlights his monstrous skull, which forces him to sleep with his head on his knees, since if he were to lie down, he would asphyxiate. On Merrick's return, he is beaten so badly by Bytes that he has to call Treves for medical help. Treves brings him back to the hospital.

Merrick is tended to by Mrs. Mothershead, the formidable matron, as the other nurses are too frightened of him. Mr. Carr Gomm, the hospital's Governor, is against housing Merrick, as the hospital does not accept "incurables." To prove that Merrick can make progress, Treves trains him to say a few conversational sentences. Carr Gomm sees through this ruse, but as he is leaving, Merrick begins to recite the 23rd Psalm, and continues past the part of the Psalm that Treves taught him. Merrick tells the doctors that he knows how to read, and has memorized the 23rd Psalm because it is his favourite. Carr Gomm permits him to stay, and Merrick spends his time practising conversation with Treves and building a model of a cathedral he sees from his window.

Merrick has tea with Treves and his wife, and is so overwhelmed by their kindness, he shows them his mother's picture. He believes he must have been a "disappointment" to his mother, but hopes she would be proud to see him with his "lovely friends". Merrick begins to take guests in his rooms, including the actress Madge Kendal, who introduces him to the work of Shakespeare. Merrick quickly becomes an object of curiosity to high society, and Mrs. Mothershead expresses concerns that he is still being put on display as a freak. Treves begins to question the morality of his own actions. Meanwhile, a night porter named Jim starts selling tickets to locals, who come at night to gawk at the "Elephant Man".

The issue of Merrick's residence is challenged at a hospital council meeting, but he is guaranteed permanent residence by command of the hospital's royal patron, Queen Victoria, who sends word with her daughter-in-law Alexandra. However, Merrick is soon kidnapped by Bytes during one of Jim's raucous late-night showings. Bytes leaves England and takes Merrick on the road as a circus attraction once again. A witness reports to Treves, who confronts Jim about what he has done, and Mothershead fires him.

Merrick is forced to be an "attraction" again, but during a "show" in Belgium, Merrick, who is weak and dying, collapses, causing a drunken Bytes to lock him in a cage and leave him to die. Merrick manages to escape from Bytes with the help of his fellow freakshow attractions. Upon returning to London, he is harassed through Liverpool Street station by several young boys and accidentally knocks down a young girl. Merrick is chased, unmasked, and cornered by an angry mob. He cries, "I am not an elephant! I am not an animal! I am a human being! I ... am ... a ... man!" before collapsing. Policemen return Merrick to the hospital and Treves. He recovers some of his health, but is dying of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Treves and Mothershead take Merrick to see one of Mrs Kendal's shows at the theatre, and Kendal dedicates the performance to him. A proud Merrick receives a standing ovation from the audience.

Back at the hospital, Merrick thanks Treves for all he has done, and completes his church model. He lies down on his back in bed, imitating a sleeping child in a picture on his wall, and dies in his sleep. Merrick is consoled by a vision of his mother, who quotes Lord Tennyson's "Nothing Will Die".

Cast

- Anthony Hopkins as Frederick Treves, a doctor who takes John from the freakshow to work in the hospital

- John Hurt as John Merrick, an intelligent, friendly and kind-hearted man who is feared by most people in his society because of his severe deformity

- Hannah Gordon as Ann Treves

- Anne Bancroft as Madge Kendal

- John Gielgud as Francis Carr Gomm

- Wendy Hiller as Mrs Mothershead

- Freddie Jones as Mr Bytes, the evil ringmaster (based on Tom Norman[4])

- Michael Elphick as Jim, the dishonest night porter

- Dexter Fletcher as Bytes' boy

- Helen Ryan as Alexandra, Princess of Wales

- John Standing as Fox

- Lesley Dunlop as Nora, Merrick's nurse

- Phoebe Nicholls (picture)/Lydia Lisle (footage) as Mary Jane Merrick

- Morgan Sheppard as man in pub

- Kenny Baker as plumed dwarf

- Pat Gorman as Fairground Bobby

- Pauline Quirke as prostitute

- Nula Conwell as Nurse Kathleen, one of Merrick's nurses[5]

Production

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2010) |

Jonathan Sanger, the film's producer, optioned the script from the writers Christopher Devore and Eric Bergren after receiving the script from his babysitter. Sanger had been working as Mel Brooks' assistant director on High Anxiety. Sanger showed Brooks the script, whereupon he decided to help finance the film through Brooksfilms, his new company. Brooks' personal assistant, Stuart Cornfeld, suggested David Lynch to Sanger.[6][7]

Sanger met Lynch and they shared scripts they were working on (The Elephant Man and Lynch's Ronnie Rocket). Lynch told Sanger that he would love to direct the script after reading it, and Sanger endorsed him after hearing Lynch's ideas. However, Brooks had not heard of Lynch at the time. Sanger and Cornfeld set up a screening of Eraserhead at a screening room at 20th Century Fox, and Brooks loved it and enthusiastically let Lynch direct the film. By his own request, Brooks was not credited as executive producer to ensure that audiences would not expect a comedy after seeing his name attached to the film.[8]

Four million dollars of the budget was raised from Fred Silverman of NBC. The remaining one million came from EMI Films.[9]

For his second feature and first studio film, albeit one independently financed,[10] Lynch provided the musical direction and sound design. Lynch tried to design the make-up himself too but the design didn't work.[8] The makeup, now supervised by Christopher Tucker, was based on direct casts of Merrick's body, which had been kept in the Royal London Hospital's private museum. The makeup took seven to eight hours to apply each day and two hours to delicately remove. John Hurt would arrive on set at 5am and shoot his scenes from noon until 10pm. After his first experience of the inconvenience of having to apply the makeup and perform with it, he called his girlfriend, saying, "I think they have finally managed to make me hate acting."

Because of the strain on the actor, he worked alternate days.[8] Lynch originally wanted Jack Nance for the title character. "But it just wasn't in the cards", Lynch says; the role went to John Hurt after Brooks, Lynch and Sanger saw his performance in The Naked Civil Servant as Quentin Crisp.[11]

Lynch bookended the film with surrealist sequences centred around Merrick's mother and her death. Lynch used Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings to underline the end of the film and Merrick's own death. The film's composer, John Morris, argued against using the music, stating that "this piece is going to be used over and over and over again in the future... And every time it's used in a film it's going to diminish the effect of the scene."[12]

When Lynch and Sanger screened The Elephant Man for Brooks after they returned from England with a cut, Brooks suggested some minor cuts but told them that the film would be released as they had made it.

There had been a West End play about Merrick called The Elephant Man, which was enjoying a successful run on Broadway at the time of the film's production. The producers sued Brooksfilms over the use of the title.[13]

Reception

Critical response

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 93% based on 54 reviews, with an average score of 8.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "David Lynch's relatively straight second feature finds an admirable synthesis of compassion and restraint in treating its subject, and features outstanding performances by John Hurt and Anthony Hopkins."[14] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 78 out of 100 based on 16 critic reviews, indicating "generally favourable reviews".[15]

Vincent Canby wrote: "Mr. Hurt is truly remarkable. It can't be easy to act under such a heavy mask ... the physical production is beautiful, especially Freddie Francis's black-and-white photography."[16]

A small number of critics were less favourable. Roger Ebert gave it 2/4 stars, writing: "I kept asking myself what the film was really trying to say about the human condition as reflected by John Merrick, and I kept drawing blanks."[17] In the book The Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture, Nadja Durbach describes the work as 'much more mawkish and moralising than one would expect from the leading postmodern surrealist filmmaker' and 'unashamedly sentimental'. She blamed this mawkishness on the use of Treves's memoirs as source material.[18]

The Elephant Man has since been ranked among the best films of the 1980s in Time Out (where it placed 19th)[19] and Paste (56th).[20] The film also received five votes in the 2012 Sight & Sound polls.[21]

Box office

In Japan, it was the second highest-grossing foreign film of the year with theatrical rentals of 2.45 billion Yen, behind only The Empire Strikes Back.[22]

Accolades

The Elephant Man was nominated for eight Academy Awards,[23] tying Raging Bull at the 53rd Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Actor in a Leading Role (John Hurt),[24] Art Direction-Set Decoration (Stuart Craig, Robert Cartwright, Hugh Scaife), Best Costume Design, Best Director, Best Film Editing, Music: Original Score, and Writing: Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium.[25] However, the film did not win any.

People in the industry were appalled that the film was not going to be honoured for its make-up effects when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its nominations at the time. A letter of protest was sent to the Academy's Board of Governors requesting to give the film an honorary award. The Academy refused, but in response to the outcry, they decided to give the make-up artists their own category. A year later, the Academy Award for Best Makeup category was introduced with An American Werewolf in London as its first recipient.[8][26]

It did win the BAFTA Award for Best Film, as well as other BAFTA Awards for Best Actor (John Hurt) and Best Production Design, and was nominated for four others: Direction, Screenplay, Cinematography and Editing.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- John Merrick: "I am not an animal! I am a human being. I am a man." – Nominated[27]

Home media

There have been many releases of the film on VHS, Betamax, CED, LaserDisc, and DVD. The DVD version was released on December 11, 2001 by Paramount Home Entertainment.[28] The version released as part of the David Lynch Lime Green Box includes several interviews with John Hurt and David Lynch and a Joseph Merrick documentary.[29] This material is also available on the exclusive treatment on the European market as part of Optimum Releasing's StudioCanal Collection.[30] The film has been available on Blu-ray since 2009 throughout Europe and in Australia & Japan but not in the US (however the discs will play in both region A & B players[31]).

A 4K restoration (created from the original camera negative and supervised by David Lynch) was carried out for the film's 40th anniversary and was released in a director-approved special edition Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection in the US on September 29, 2020.[32] The restoration was also released on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray (including a remastered Blu-ray) in the UK in April 2020.[33]

The tie-in novel was written by Christine Sparks and published by Ballantine Books in 1980.

Soundtrack

The musical score of The Elephant Man was composed and conducted by John Morris, and it was performed by the National Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1980, the company 20th Century Fox Records published this film's original musical score as both an LP album and as a Cassette in the United States. Its front cover artwork features a masked John Merrick against a backdrop of smoke, as seen on the advance theatrical poster for the film.

In 1994, the first compact disc (CD) issue of the film score was made by the company Milan, which specializes in film scores and soundtrack albums.[34]

Track listing for the first U.S. release on LP

Side one

- "The Elephant Man Theme" – 3:46

- "Dr. Treves Visits the Freak Show and Elephant Man" – 4:08

- "John Merrick and Psalm" – 1:17

- "John Merrick and Mrs. Kendal" – 2:03

- "The Nightmare" – 4:39

Side two

- "Mrs. Kendal's Theater and Poetry Reading" – 1:58

- "The Belgian Circus Episode" – 3:00

- "Train Station" – 1:35

- "Pantomime" – 2:20

- "Adagio for Strings" – 5:52

- "Recapitulation" – 5:35

Cultural influence

The Jam's former bassist Bruce Foxton was inspired strongly by the film, and in response wrote the song "Freak" with the single's cover even making a reference to the film.[35]

Actor Bradley Cooper credits watching the film with his father as a child as his inspiration to become an actor. Cooper played the character on Broadway in 2013.[36]

Musician Steven Wilson has stated The Elephant Man to be his favourite film of all time.[citation needed]

In season 3, episode 21 of The Simpsons, "Black Widower", Lisa daydreams of Aunt Selma's new boyfriend as the Elephant Man.[citation needed]

British TV presenter Karl Pilkington often has cited it as his favourite film. Pilkington's love for the film brought many new features to his various podcasts and radio shows.[37]

Musician Michael Stipe loves the film and cites it as an inspiration for the R.E.M. song "Carnival of Sorts (Boxcars)".[38] Another R.E.M. song, "New Test Leper", quotes the line "I am not an animal."[citation needed]

Musician Nicole Dollanganger featured a sample of the film in her 2012 song "Cries of the Elephant Man Bones".[citation needed]

Musician Mylène Farmer's song "Psychiatric" from the 1991 album L'Autre... is a tribute to the film and John Hurt's voice is sampled throughout the song, repeating several times: "I'm a human being, I'm not an animal".[citation needed]

"Adagio for Strings" is a song inspired by the Motion Picture Soundtrack Elephant Man and produced by Dutch DJ Tiësto. It was first released in January 2005 as the fourth single from the album Just Be. The song is a cover of the original composition by Samuel Barber. In 2013, it was voted by Mixmag readers as the second greatest dance record of all time.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ The Times, October 8, 1980, in large article on page 9 by John Higgins: "The Elephant Man, which opens tomorrow at the ABC, Shaftesbury Avenue, is also likely to establish the reputation of its director, David Lynch." Read in The Times Digital Archive on October 28, 2013

- ^ "The Elephant Man (1980)". BFI. Retrieved February 22, 2019

- ^ "The Elephant Man (1980)", Box Office Mojo, retrieved July 4, 2010

- ^ von Tunzelmann, Alex (December 10, 2009). "The Elephant Man: close to the memoirs but not the man". The Guardian. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "The Elephant Man (1980) – Full Cast & Crew". IMDb. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "'How does a guy known for fart jokes make The Elephant Man?'". The Guardian. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "A Brief History of Mel Brooks, David Lynch and 'The Elephant Man'". Film School Rejects. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d ""The Elephant Man" Trivia". IMDB.com. USA. July 1, 2000. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Ryan, Desmond (November 3, 1985). "AT THE MOVIES: SERIOUSLY, FOLKS, THERE'S A SERIOUS MEL BROOKS". Philadelphia Inquirer. p. L.2.

- ^ Huddleston, Tom (2010), "David Lynch: interview", Time Out, archived from the original on June 4, 2010, retrieved June 16, 2010

- ^ Potter, Maximillian (August 1997). "Erased". Premiere.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (January 29, 2018). "John Morris, Composer for Mel Brooks's Films, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ SCHREGER, CHARLES (August 22, 1979). "Title Fight for 'Elephant Man'". Los Angeles Times. p. f10.

- ^ "The Elephant Man (1980)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ "The Elephant Man Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Vincent Canby (October 3, 1980). "Movie Review – The Elephant Man". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "The Elephant Man". RogerEbert.com. January 1, 1980. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Durbach (2009), p. 35

- ^ "The 30 best '80s movies". Time Out New York. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ "The 80 Best Movies of the 1980s". pastemagazine.com. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ "Votes for The Elephant Man (1980)". BFI. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ "All-Time Foreign Grossers In Japan". Variety. March 7, 1984. p. 89.

- ^ "David Lynch – Chapter 2: The Elephant Man and Dune – An Auteur In Hollywood". The British Film Resource. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean; Times, Special to the New York (February 18, 1981). "'ELEPHANT MAN' AND 'BULL' UP FOR 8 OSCARS EACH". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ "The Elephant Man". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Baseline & All Movie Guide. 2009. Archived from the original on April 12, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ Roger Clarke (March 2, 2007), "The Elephant Man", The Independent, archived from the original on November 4, 2012

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ^ Rivero, Enrique (September 27, 2001). "Extras-Packed 'Almost Famous,' 'Elephant Man' Coming to DVD". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2001. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ "The Elephant Man on StudioCanal Collection". Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "StudioCanal Collection". Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "Elephant Man (The) (Blu-ray) (1980)". www.dvdcompare.net. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "The Elephant Man (1980)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Brook, David (April 5, 2020). "The Elephant Man – Studiocanal Blu-ray". Blueprint: Review. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "Milan Records – IMDbPro". Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Jam, The – Nostalgia Central". nostalgiacentral.com. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Bradley Cooper talks about playing 'Elephant Man'". TODAY.com. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Ricky Gervais Explains The Mind Of Karl Pilkington @ TeamCoco.com". teamcoco.com. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- ^ "The Story Of R.E.M. Without The Greatest Hits". npr.org. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

Further reading

- Shai Biderman & Assaf Tabeka. "The Monster Within: Alienation and Social Conformity in The Elephant Man" in: The Philosophy of David Lynch 207 (University Press of Kentucky, 2011).

- Durbach, Nadja (2009), "Monstrosity, Masculinity, and Medicine: Reexamining 'the Elephant Man'", The Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-25768-9, OCLC 314839375

External links

- 1980 films

- 1980s biographical drama films

- American films

- American biographical drama films

- 1980s English-language films

- American black-and-white films

- Films about disability

- Films about sideshow performers

- Circus films

- Films adapted into plays

- Drama films based on actual events

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films directed by David Lynch

- Films produced by Mel Brooks

- Brooksfilms films

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films scored by John Morris

- Best Foreign Film César Award winners

- Films set in London

- Films set in the 1880s

- Films shot in London

- Films shot at Shepperton Studios

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Cultural depictions of Joseph Merrick

- EMI Films films

- Films based on multiple works

- 1980 drama films

- Films about prejudice