Baird Auditorium: Difference between revisions

PrairieHist (talk | contribs) m Added new headings |

PrairieHist (talk | contribs) Added subheading. |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Documentation subpage}} <!-- Add categories where indicated at the bottom of this page and interwikis at Wikidata --> |

{{Documentation subpage}} <!-- Add categories where indicated at the bottom of this page and interwikis at Wikidata --> |

||

The Baird Auditorium is a multi-purpose 530-seat venue located on the ground floor of the [[Smithsonian Institution]]'s [[National Museum of Natural History]] in [[Washington, D.C.|Washington, D.C]].. |

The Baird Auditorium is a multi-purpose 530-seat venue located on the ground floor of the [[Smithsonian Institution]]'s [[National Museum of Natural History]] in [[Washington, D.C.|Washington, D.C]].. |

||

{{Infobox building |

{{Infobox building |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

As one of the oldest public performance venues and lecture halls at the [[Smithsonian Institution|Smithsonian]], the Baird Auditorium's history of events is as diverse as the Smithsonian itself. Located beneath the [[National Museum of Natural History]]'s rotunda, the Baird Auditorium is named for the second [[Secretary of the Smithsonian]] [[Spencer Fullerton Baird]]. |

|||

Located beneath the [[National Museum of Natural History]]'s rotunda, the Baird Auditorium is named for the second [[Secretary of the Smithsonian]] [[Spencer Fullerton Baird]]. The Baird Auditorium was completed in 1909, designed and built by the R. Guastavino Company under the direction of [[Rafael Guastavino]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=November 17, 2015 |title=How Do You Support a 5-ton Elephant? |url=https://bookwormhistory.com/2015/11/17/how-do-you-support-a-5-ton-elephant/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220824174121/https://bookwormhistory.com/2015/11/17/how-do-you-support-a-5-ton-elephant/ |archive-date=August 23, 2022 |access-date=August 23, 2022 |website=Bookworm History}}</ref> The Baird Auditorium is one of the finest examples of the [[Guastavino tile arch system|'''Guastavino tile arch system''']], inspired by the [[Catalan vault]], in the United States. |

|||

=== Architecture === |

|||

The [[American Institute of Architects]] calls the Baird Auditorium the museum's "greatest interior space."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Moeller |first=Gerard Martin |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1272882861 |title=AIA guide to the architecture of Washington, DC |date=2022 |others=American Institute of Architects |isbn=978-1-4214-4384-3 |edition=6th |location=Baltimore |pages=46 |oclc=1272882861}}</ref> According to architectural scholar Dr. [[John Ochsendorf]], the Baird Auditorium's "daring geometry" in tile construction by the [[Guastavino tile|Guastavino]] company "spans 90 feet (27 meters) with a remarkable shallow dome in acoustical tile, and could only have been built by a company with decades of experience in tile vaulting."<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Ochsendorf |first=John Allen |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/769114424 |title=Guastavino vaulting : the art of structural tile |date=2010 |publisher=Princeton Architectural Press |others=Michael Freeman |isbn=1-56898-741-2 |location=New York |page= |pages=211 |oclc=769114424}}</ref> |

The Baird Auditorium was completed in 1909, designed and built by the R. Guastavino Company under the direction of [[Rafael Guastavino]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=November 17, 2015 |title=How Do You Support a 5-ton Elephant? |url=https://bookwormhistory.com/2015/11/17/how-do-you-support-a-5-ton-elephant/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220824174121/https://bookwormhistory.com/2015/11/17/how-do-you-support-a-5-ton-elephant/ |archive-date=August 23, 2022 |access-date=August 23, 2022 |website=Bookworm History}}</ref> The Baird Auditorium is one of the finest examples of the [[Guastavino tile arch system|'''Guastavino tile arch system''']], inspired by the [[Catalan vault]], in the United States. The [[American Institute of Architects]] calls the Baird Auditorium the museum's "greatest interior space."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Moeller |first=Gerard Martin |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1272882861 |title=AIA guide to the architecture of Washington, DC |date=2022 |others=American Institute of Architects |isbn=978-1-4214-4384-3 |edition=6th |location=Baltimore |pages=46 |oclc=1272882861}}</ref> According to architectural scholar Dr. [[John Ochsendorf]], the Baird Auditorium's "daring geometry" in tile construction by the [[Guastavino tile|Guastavino]] company "spans 90 feet (27 meters) with a remarkable shallow dome in acoustical tile, and could only have been built by a company with decades of experience in tile vaulting."<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Ochsendorf |first=John Allen |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/769114424 |title=Guastavino vaulting : the art of structural tile |date=2010 |publisher=Princeton Architectural Press |others=Michael Freeman |isbn=1-56898-741-2 |location=New York |page= |pages=211 |oclc=769114424}}</ref> |

||

== Notable Speaking Engagements == |

== Notable Speaking Engagements == |

||

Revision as of 01:25, 26 August 2022

This article, Baird Auditorium, has recently been created via the Articles for creation process. Please check to see if the reviewer has accidentally left this template after accepting the draft and take appropriate action as necessary.

Reviewer tools: Inform author |

The Baird Auditorium is a multi-purpose 530-seat venue located on the ground floor of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C..

| Baird Auditorium | |

|---|---|

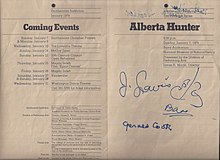

Photograph by: Unknown, circa 1911. View of the newly completed Baird Auditorium, looking towards the stage, in the new National Museum Building, now known as the National Museum of Natural History. The auditorium is located under the Rotunda. The elegant classically inspired room features a domed ceiling of Guastavino tiles. | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | |

| Address | 10th St. & Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20560, United States |

| Town or city | Washington, D.C. |

| Country | USA |

| Owner | Smithsonian Institution |

| Other information | |

| Seating capacity | 530 |

History

As one of the oldest public performance venues and lecture halls at the Smithsonian, the Baird Auditorium's history of events is as diverse as the Smithsonian itself. Located beneath the National Museum of Natural History's rotunda, the Baird Auditorium is named for the second Secretary of the Smithsonian Spencer Fullerton Baird.

Architecture

The Baird Auditorium was completed in 1909, designed and built by the R. Guastavino Company under the direction of Rafael Guastavino.[1] The Baird Auditorium is one of the finest examples of the Guastavino tile arch system, inspired by the Catalan vault, in the United States. The American Institute of Architects calls the Baird Auditorium the museum's "greatest interior space."[2] According to architectural scholar Dr. John Ochsendorf, the Baird Auditorium's "daring geometry" in tile construction by the Guastavino company "spans 90 feet (27 meters) with a remarkable shallow dome in acoustical tile, and could only have been built by a company with decades of experience in tile vaulting."[3]

Notable Speaking Engagements

Science

The Baird Auditorium was the location of the 'Great Debate' in the field of astronomy, also called the 'Shapley–Curtis Debate,' on April 26, 1920 on the topics of spiral nebulae and the size of the universe. Canadian anthropologist Wade Davis spoke in the Baird on April 27, 2005.[4]

Arts and Culture

On October 31, 1933, African American writer and philosopher Alain Locke gave a lecture and screened films from the Harmon Foundation as part of the Smithsonian exhibition, "Exhibition of Works by Negro Artists," and sponsored by Carter G. Woodson's Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.[5] (At the time the National Mall was a desegregated area of Washington, making the Baird one of the few racially integrated theatres prior to the National Theatre's desegregation in May 1952.[6]) According to VCU professor Tobias Wofford, "On Woodson’s invitation, Locke delivered a slide lecture to the ASNLH congregants in the auditorium adjacent to the exhibition space. The lecture explored the links between African and African American art."[7] While Locke's "address was noted prominently by most of the accounts of the exhibition," Locke himself viewed it as participating in "a reaction of racial vanity."[7] Seventy-nine years later on October 31, 2012, six-time world champion boxer and Olympic gold medalist Sugar Ray Leonard spoke on the same stage in a conversation with former Washington Redskins and Washington Senators stadium announcer, Phil Hochberg.[8]

Politics

In May of 1995 Sirikit the queen of Thailand spoke in the Baird Auditorium after "reviewing the museum's Thai collections."[9]

Musical Performances

The Baird Auditorium has a long and illustrious history of musical performances. Mother Maybelle Carter performed in the Baird just three years before her passing, accompanied b her daughter Helen Carter Jones, her grandson David Carter Jones, Mike Seeger, and Ralph Rinzler, on May 18, 1975; National Public Radio recorded the performance as "Folk Festival USA," part of the Smithsonian's "Women in Country Music" series.[10] Merle Travis gave a country guitar music concert in the Baird Auditorium on October 23, 1976.[11] In early February 1977, Muddy Waters performed in the Baird as part of the Smithsonian Institution's blues series presented by the Division of Performing Arts.[12]

Blues singer Alberta Hunter performed at the Baird on several occasions during her late-1970s 'comeback' career period, including: on January 7, 1977[13], and in a filmed performance on November 29, 1981, which received commercial home video release as, "Alberta Hunter: Jazz at the Smithsonian," originally released in 1982.[14]

Pete Seeger and Sweet Honey in the Rock performed an evening of "protest songs from Colonial times to today," together on the Baird's stage on January 8, 1978.[15] On June 2, 1978 the "Texas Troubador" Ernest Tubb performed as part of the Smithsonian's American Country Music series.[16]

Jazz great Wynton Marsalis performed a Young People's Concert in the Baird Auditorium with the Wynton Marsalis Septet on June 7, 1994.[17]

David Byrne promoted his 2012 book, "How Music Works," with a talk held in the Baird Auditorium on October 1, 2012.[18]

References

- ^ "How Do You Support a 5-ton Elephant?". Bookworm History. November 17, 2015. Archived from the original on August 23, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; August 24, 2022 suggested (help) - ^ Moeller, Gerard Martin (2022). AIA guide to the architecture of Washington, DC. American Institute of Architects (6th ed.). Baltimore. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4214-4384-3. OCLC 1272882861.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ochsendorf, John Allen (2010). Guastavino vaulting : the art of structural tile. Michael Freeman. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 211. ISBN 1-56898-741-2. OCLC 769114424.

- ^ "Record Wade Davis, Baird Auditorium, #1, 4/27/2005, MiniDV | Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution". collections.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Brock, Charles (Summer 2019). "Toward a History of Modernism in Washington: The 1933 Display of Art by African Americans at the Smithsonian Institution's National Gallery of Art". American Art. 33 (2).

- ^ WETA. "How Helen Hayes Helped Desegregate the National Theatre". Boundary Stones: WETA's Washington DC History Blog. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ a b Wofford, Tobias (Summer 2019). "Perspectives on the 1933 Exhibition: Herring, Locke, and Porter". American Art. 33 (2).

- ^ "THE SMITHSONIAN ASSOCIATES PRESENTS 'SUGAR RAY'S BIG FIGHT: INSIDE THE WORLD OF BOXING'". US Fed News (USA). September 17, 2012. p. 2.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1995). Annals of the Smithsonian Institution, 1995 (PDF). Washignton, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. p. 85. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "Mother Maybelle Carter and the Carter family [sound recording]. 1975-05-18. 2 sound tape reels : analog, 7 1/2 ips, full track ; 10 in.manuscripts 1 folder. Local shelving no.: LWO 8906AFS 18089-18090AFC 1976/018". Library of Congress, American Folklife Center.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 76 (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "October at the Smithsonian Institution" (PDF). The Smithsonian Torch. Vol. 76–9. October 1976. p. 5. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Harris-Hurd, Laura (February 5, 1977). "Muddy Waters Warms Washington Crowd". New York Amsterdam News. pp. D15.

- ^ Sumrall, Harry (January 8, 1979). "Alberta Hunter". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ United States Copyright Registration. Type of Work: Motion Picture; Registration Number / Date: PA0000163741 / 1982-12-17; Title: Alberta Hunter / a production of Adler Enterprises, Ltd.; produced and directed by Clarke Santee [i.e. Clark Santee] and Delia Gravel Santee. Imprint: McLean, Va.: Distributed by Adler Video Marketing, c1982. Description: 1 videocassette (58 min.) : sd., col. ; 3/4 in.; Series: Jazz at the Smithsonian. Notes: Host: Willis Conover. Deposit includes descriptive folder (4 p.); Copyright Claimant: Adler Enterprises, Ltd.; Date of Creation: 1981. Date of Publication: 1982-04-22. Authorship on Application: Adler Enterprises, Ltd., employer for hire. Copyright Note: C.O. correspondence.

- ^ Richmond, Phyllis C. (January 8, 1978). "Where Has All the Protest Gone?". The Washington Post. p. 39.

- ^ Summers, K.C. (June 2, 1978). "Ernest Tubb". The Washington Post. p. 3.

- ^ "Record Wynton Marsalis Talks Jazz | Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution". collections.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ "THE SMITHSONIAN ASSOCIATES PRESENTS 'DAVID BYRNE IN CONVERSATION'". US Fed News (USA). September 17, 2012. p. 2.

External links

- "Alberta Hunter: Jazz at the Smithsonian" (1982) home video release of her 1981 performance at the Baird Auditorium on YouTube