Lutsk: Difference between revisions

→Notable people: added Svitlana Winnikow |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

Upon Nazi occupation most of the Jewish inhabitants of the city were forced into a new [[Łuck Ghetto]] ({{lang-de|Ghetto Luzk}}) and then murdered at the execution site on Górka Połonka hill not far from the city.<ref name="wolyn.ovh">Andrzej Mielcarek, [https://web.archive.org/web/20070328024046/http://wolyn.ovh.org/opisy/hnidawa-07.html Wieś i kolonia Hnidawa, inaczej Gnidawa, powiat Łuck]; [https://web.archive.org/web/20070917144326/http://wolyn.ovh.org/opisy/polonka-07.html Gromada Połonka.] Interactive 1936 map included. ''Strony o Wołyniu'' Wolyn.ovh.org in Polish. Retrieved July 24, 2015.</ref> In total, more than 25,000 Jews were executed there at point-blank range,<ref name="Polonka">Yad Vashem, {{YouTube |id=Q87bYVp0EGA |title=Mass-murder of Łuck Jews at Gurka Polonka in August 1942}} Note: village Połonka ({{lang-pl|Górka Połonka}} or its [https://web.archive.org/web/20080720074205/http://www.wolyn.ovh.org/opisy/gorka_polonka-07.html Połonka Little Hill] subdivision) is misspelled in the documentary, with testimony of eyewitness [[Shmuel Shilo]]. Retrieved July 24, 2015.</ref> men, women and children.<ref name="YIVO">YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, [http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Lutsk Lutsk.] Ghetto history. Retrieved 22 July 2015.</ref> The Łuck Ghetto was liquidated entirely through ''the Holocaust by bullets''.<ref name="National Geographic">{{YouTube| id= moY7kocJrTg | title= "The Holocaust by bullets" by National Geographic Channel}} Retrieved 20 July 2015.</ref> During the [[massacres of Poles in Volhynia]] approximately 10,000 Poles were murdered by the [[Ukrainian Insurgent Army]] in the area. It was captured by the [[Red Army]] on 2 February 1944. |

Upon Nazi occupation most of the Jewish inhabitants of the city were forced into a new [[Łuck Ghetto]] ({{lang-de|Ghetto Luzk}}) and then murdered at the execution site on Górka Połonka hill not far from the city.<ref name="wolyn.ovh">Andrzej Mielcarek, [https://web.archive.org/web/20070328024046/http://wolyn.ovh.org/opisy/hnidawa-07.html Wieś i kolonia Hnidawa, inaczej Gnidawa, powiat Łuck]; [https://web.archive.org/web/20070917144326/http://wolyn.ovh.org/opisy/polonka-07.html Gromada Połonka.] Interactive 1936 map included. ''Strony o Wołyniu'' Wolyn.ovh.org in Polish. Retrieved July 24, 2015.</ref> In total, more than 25,000 Jews were executed there at point-blank range,<ref name="Polonka">Yad Vashem, {{YouTube |id=Q87bYVp0EGA |title=Mass-murder of Łuck Jews at Gurka Polonka in August 1942}} Note: village Połonka ({{lang-pl|Górka Połonka}} or its [https://web.archive.org/web/20080720074205/http://www.wolyn.ovh.org/opisy/gorka_polonka-07.html Połonka Little Hill] subdivision) is misspelled in the documentary, with testimony of eyewitness [[Shmuel Shilo]]. Retrieved July 24, 2015.</ref> men, women and children.<ref name="YIVO">YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, [http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Lutsk Lutsk.] Ghetto history. Retrieved 22 July 2015.</ref> The Łuck Ghetto was liquidated entirely through ''the Holocaust by bullets''.<ref name="National Geographic">{{YouTube| id= moY7kocJrTg | title= "The Holocaust by bullets" by National Geographic Channel}} Retrieved 20 July 2015.</ref> During the [[massacres of Poles in Volhynia]] approximately 10,000 Poles were murdered by the [[Ukrainian Insurgent Army]] in the area. It was captured by the [[Red Army]] on 2 February 1944. |

||

=== |

===Postwar=== |

||

After the end of the war, the remaining Polish inhabitants of the city were expelled, mostly to the areas that is sometimes referred to as the Polish [[Regained Territories]]. The city became an industrial centre in the [[Ukrainian SSR]]. The major changes in the city's demographics had the final result that by the end of the war the city was almost entirely Ukrainian. During the [[Cold War]], the city hosted the [[Lutsk (air base)|Lutsk air base]]. |

|||

As one of the largest cities in Western Ukraine, Lutsk became the seat of a General Consulate of Poland in 2003.<ref> |

As one of the largest cities in Western Ukraine, Lutsk became the seat of a General Consulate of Poland in 2003.<ref> |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

On 21 July 2020, [[Lutsk hostage crisis| |

On 21 July 2020, a [[Lutsk hostage crisis|hostage crisis]] took place]], involving a man armed with a firearm and explosives who stormed a bus and took 16 people [[hostage]] at about 9:25 a.m. Police said that they had identified the hostagetaker and that he had expressed a dissatisfaction with "Ukraine's system" on social media. [[Ukrainien President]] [[Volodymyr Zelenskyy]] said that shots gas been heard and that the bus had been damaged. The incident led to police blocking off the city centre. The standoff was eventually resolved after several hours, with all of the hostages being freed and the hostagetaker being arrested.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://apnews.com/9f60460ff774acb4a40a0c5198bd072c|title=Police: Armed man holding some 20 people hostage in Ukraine|publisher=Associated Press|date=21 July 2020|access-date=21 July 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-hostages/shots-heard-as-bus-passengers-taken-hostage-in-western-ukraine-idUSKCN24M0UH|title=Shots heard as bus passengers taken hostage in western Ukraine|publisher=Reuters|date=21 July 2020|access-date=21 July 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53489527|title=Ukraine hostage crisis: Police in Lutsk end stand-off|work=BBC News|date=21 July 2020|access-date=21 July 2020}}</ref> |

||

=== 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine === |

=== 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine === |

||

Revision as of 21:48, 9 September 2022

Lutsk

Луцьк | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Coordinates: 50°45′00″N 25°20′09″E / 50.75000°N 25.33583°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Municipality | Lutsk |

| Founded | 1085 |

| City Rights | 1432 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ihor Polishchuk |

| Area | |

• Total | 42.00 km2 (16.22 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 174 m (571 ft) |

| Population (2021)[1] | |

• Total | 217,197 |

| • Density | 4,830/km2 (12,500/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 43000 |

| Area code | +380 332 |

| Sister cities | Lublin |

| Website | lutskrada |

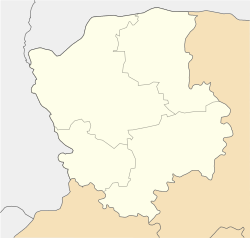

Lutsk (Template:Lang-uk, IPA: [luts͜k]; Template:Lang-pl [wutsk]; Template:Lang-yi) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding Lutsk Raion (district) within the oblast, though it is not a part of the raion. Lutsk has the status of a city of oblast significance, equivalent to that of a raion, and a population of 217,197 (2021 est.)[1]

It is a historical, political, cultural and religious center of Volyn.

Etymology

Lutsk is an ancient Slavic town, mentioned in the Hypatian Chronicle as Luchesk in the records of 1085. The etymology of the name is unclear. There are three hypotheses: the name may have been derived from the Old Slavic word luka (an arc or bend in a river), or the name may have originated from Luka (the chieftain of the Dulebs), an ancient Slavic tribe living in this area. The name may also have been created after Luchanii (Luchans), an ancient branch of the tribe mentioned above. Its historical name in Ukrainian is "Луцьк".

History

According to the legend, Luchesk dates from the 7th century. The first known documentary reference dates were from the year 1085. The town served as the capital of the Principality of Halych-Volynia (founded in 1199) until the rise of Volodymyr. The town grew around a wooden stronghold built by a local branch of the Rurik Dynasty. At certain times the location functioned as the capital of the principality, but since there was no need for a fixed capital in medieval Europe, the town did not become an important centre of commerce or culture.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

In 1240, Tatars seized and looted the nearby town but left the castle unharmed. In 1321, George, son of Lev, the last prospective heir of Halych-Volynia, died in a battle with the forces of Gediminas, Grand Duke of Lithuania, and Lithuanian forces seized the castle. In 1349, the forces of King Casimir III of Poland captured the town, but Lithuania soon retook it.

The town began to prosper during the period of Lithuanian rule. Prince Lubart (died 1384), son of Gediminas, erected Lubart's Castle as part of his fortification programme. Vytautas the Great, Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1392 to 1430, founded the town itself by importing colonists (mostly Jews, Tatars, and Karaims). In 1427 he transferred the Catholic bishopric from Volodymyr to Luchesk. Vytautas was the last monarch to use the title of "Duke of Volhynia" and to reside in Lubart's Castle.

The town grew rapidly, and by the end of the 15th century there were 19 Orthodox and two Catholic churches. It was the seat of two Christian bishops, one Catholic and one Orthodox. Because of that, the town was sometimes nicknamed "the Volhynian Rome." The cross symbol of Lutsk features on the highest Lithuanian Presidential award, the Order of Vytautas the Great.[citation needed]

In 1429 Lutsk was the meeting place selected for a conference of monarchs hosted by Jogaila and Sophia of Halshany to deal with the Tatar threat. Those invited to attend included Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor; Vasili II of Russia, the king of Denmark; Eric of Pomerania, the Grand Master of the Livonian Order; Zisse von Rutenberg, the Duke of Szczecin Kazimierz V; Dan II, the Hospodar of Wallachia; and Prince-electors of most of the countries of Germany.

Crown of the Kingdom of Poland

In 1432, Volhynia became a fief of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and Lutsk became the seat of the governors, and later the Marshalls of the Land of Volhynia. That same year, the city was granted Magdeburg rights. In 1569, Volhynia was fully incorporated into the Polish kingdom and the town became the capital of the Volhynian Voivodeship and the Łuck powiat (Polish administrative unit). After the Union of Lublin, the local Orthodox bishop converted to Eastern Catholicism.

The town continued to prosper as an important economic centre of the region. By the mid-17th century, Łuck had approximately 50,000 inhabitants and was one of the largest towns in the area. During the Khmelnytskyi Uprising, the town was seized by the forces of Colonel Kolodko. Up to 4,000 people were slaughtered, approximately 35,000 fled, and the town was looted and partially burnt. It never fully recovered. In 1781, the city was struck by a fire which destroyed 440 houses, both cathedrals, and several other churches.

Russian Empire

In 1795, as a result of the Partitions of Poland, the Russian Empire annexed Lutsk. The Voivodeship was liquidated and the town lost its significance as the capital of the province (which was moved to Zhytomyr). After the November Uprising (1830–1831), efforts increased to remove Polish influence. Russian became the dominant language in official circles. Though, the population continued to speak Ukrainian; the Polish population spoke Polish; and the Jewish population spoke Yiddish (only in private circles). The Greek Catholic churches were turned into Orthodox Christian ones, which led to the self-liquidation of the Uniates here. In 1845, another great fire struck the city, resulting in a further depopulation.

In 1850, three major forts were built around Lutsk, and the town became a small fortress called Mikhailogorod. During the First World War, the town was seized by Austria-Hungary on August 29, 1915. The town sustained a small amount of damage. During more than a year of Austro-Hungarian occupation, Lutsk became an important military centre with the headquarters of the IV Army under Archduke Josef Ferdinand stationed there. A plague of epidemic typhus decimated the city's inhabitants.

On June 4, 1916, four Russian armies under general Aleksei Brusilov started what later became known as the Brusilov Offensive. After up to three days of heavy artillery barrage, the Battle of Lutsk began. On June 7, 1916, the Russian forces reconquered the city. After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1917, the city was seized by Germany on February 7, 1918. On February 22, 1918, the town was transferred by the withdrawing German army to the forces loyal to Symon Petlura.

Second Polish Republic

During the Polish-Bolshevik War, on May 16, 1919, Lutsk was taken over by the forces of Poland's Blue Army after a heavy battle with the Red Army. The city was devastated and largely depopulated. It witnessed the Soviet counter-offensive of 1920 and was taken on 12 July 1920. It was recaptured by Poland's 45th Rifles regiment and field artillery on September 15, 1920.[2] According to American sociologist Alexander Gella "the Polish victory [over the Red Army] had gained twenty years of independence not only for Poland, but at least for an entire central part of Europe.[3] Łuck was designated by the newly-reborn nation of Poland as the capital of the Wołyń Voivodeship.

The city was connected by railroad to Lviv (then Lwów) and Przemyśl. Several brand new factories were built both in Łuck and on its outskirts producing farming equipment, wood, and leather products among other consumer goods. New mills and breweries opened. An orphanage was built, and a big new bursary. The first high-school was soon inaugurated. In 1937, an airport was established in Łuck with an area of 69 hectares (170 acres).[2]

The 13th Kresowy Light Artillery Regiment was stationed in the city, together with a Łuck National Defense (Poland) Battalion. In 1938, construction of a large modern radio transmitter began in the city (see Polish Radio Łuck). As of January 1, 1939, Łuck had 39,000 inhabitants (approximately 17,500 Jews and 13,500 Poles). The powiat formed around the town had 316,970 inhabitants, including 59% Ukrainians, 19.5% Poles, 14% Jews and approximately 23,000 Czechs and Germans.

World War II

On Thursday, September 7, 1939 at app. 5 p.m., the Polish government, which had left Warsaw the day before, arrived at Łuck. German intelligence quickly found out about it, and the city was twice bombed by the Luftwaffe: on Sept. 11, and Sept. 14. After panzer units of the Wehrmacht had crossed the Bug river, on September 14, the government of Poland left Łuck and headed southwards, to Kosow Huculski, which at that time was located near the Polish–Romanian border.

As a result of the invasion of Poland from both sides and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Łuck, along with the rest of western Volyn, was annexed by the Soviet Union. Most of the factories (including the almost-finished radio station) were dismantled and sent east to Russia. Approximately 10,000 of the city's Polish inhabitants (chiefly ethnic Poles, but also Polish Jews) were deported in cattle trucks to Kazakhstan and 1,550 were arrested by the NKVD.[4][5]

After the start of Operation Barbarossa the city was captured by the Wehrmacht on 25 June 1941. Thousands of Polish and Ukrainian prisoners were shot by the retreating NKVD responsible for political prisons. The inmates were offered amnesty and in the morning of June 23 ordered to exit the building en masse. They were gunned down by Soviet tanks.[6] Some 4,000 captives including Poles, Jews and Ukrainians were massacred.[7]

Upon Nazi occupation most of the Jewish inhabitants of the city were forced into a new Łuck Ghetto (Template:Lang-de) and then murdered at the execution site on Górka Połonka hill not far from the city.[8] In total, more than 25,000 Jews were executed there at point-blank range,[9] men, women and children.[10] The Łuck Ghetto was liquidated entirely through the Holocaust by bullets.[11] During the massacres of Poles in Volhynia approximately 10,000 Poles were murdered by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in the area. It was captured by the Red Army on 2 February 1944.

Postwar

After the end of the war, the remaining Polish inhabitants of the city were expelled, mostly to the areas that is sometimes referred to as the Polish Regained Territories. The city became an industrial centre in the Ukrainian SSR. The major changes in the city's demographics had the final result that by the end of the war the city was almost entirely Ukrainian. During the Cold War, the city hosted the Lutsk air base.

As one of the largest cities in Western Ukraine, Lutsk became the seat of a General Consulate of Poland in 2003.[12]

On 21 July 2020, a hostage crisis took place]], involving a man armed with a firearm and explosives who stormed a bus and took 16 people hostage at about 9:25 a.m. Police said that they had identified the hostagetaker and that he had expressed a dissatisfaction with "Ukraine's system" on social media. Ukrainien President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that shots gas been heard and that the bus had been damaged. The incident led to police blocking off the city centre. The standoff was eventually resolved after several hours, with all of the hostages being freed and the hostagetaker being arrested.[13][14][15]

2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine

On 11 March 2022, as part of the Russian invasion, the Russian army fired four missiles at Lutsk military airfield killing two Ukrainian servicemen and wounding six.[16] On 28 March, Lutsk was struck by another Russian missile.[17]

Climate

Lutsk has a humid continental climate (Dfb in the Köppen climate classification).

| Climate data for Lutsk (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

0.7 (33.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.5 (32.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

7.9 (46.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.7 (21.7) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 25.3 (1.00) |

25.9 (1.02) |

29.1 (1.15) |

36.9 (1.45) |

60.5 (2.38) |

73.3 (2.89) |

86.7 (3.41) |

57.0 (2.24) |

53.8 (2.12) |

37.6 (1.48) |

35.4 (1.39) |

34.6 (1.36) |

556.1 (21.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.8 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 8.7 | 96.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87.6 | 85.8 | 80.6 | 71.2 | 70.3 | 73.8 | 74.5 | 74.4 | 79.7 | 82.7 | 87.9 | 89.2 | 79.8 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[18] | |||||||||||||

Industry and commerce

Lutsk is an important centre of industry. Factories producing cars, shoes, bearings, furniture, machines and electronics, as well as weaveries, steel mills and a chemical plant are located in the area.

- VGP JSC – manufacture of sanitary and hygienic products

- LuAZ – automobile-manufacturing plant, part of Bogdan group

- SKF – manufacture of bearings, seals, lubrication and lubrication systems, maintenance products, mechatronics products, power transmission products and related services globally

- Modern-Expo Group – one of the largest manufacturers and suppliers of equipment (metal shelving, high racks systems, checkouts, catering equipment, refrigeration equipment, POS-equipment and guidance systems) for retail and warehouse use in Central and Eastern Europe.

- Lutsk is the capital of the Drupal web development

Places of interest

- Lubart's Castle. The Upper Castle from the 13th century and the Lower Castle from the 14th century

- Saint Peter and Paul Cathedral. A Catholic cathedral built 1610 as a Jesuit church, reconstructed in 1781

- Great Synagogue built in 1626–1629

- Holy Trinity Orthodox Cathedral built 1755 as a church and monastery of Bernardines

- Lutheran Church

- Complex of Lutsk Orthodox Fellowship

- Market square

- Lesya Ukrainka street

- Monasteries, both Catholic and Orthodox: Basilians (17th century), Dominicans (17th century), Trinitarians (18th century) and Charites (18th century)

- Two 16th century Greek-Catholic churches

- Lutsk compact overhead powerline, a powerline of unusual type.

- One of the longest buildings in the world: Apartment house on Sobornosti av. and Molodyozhi st. (50.761219°N, 25.368719°E) Length: 1750 m.

-

St. Peter and Paul Cathedral

-

The Great Synagogue in Lutsk

-

Holy Trinity Cathedral

Theatres and museums

- Drama Theatre, built in 1939 (uk)

- Children's Puppet Theater

- Museum of Regional Studies. Address: Shopena St. 20

- Museum of Ukrainian army and ammunition opened in 1999. Address: Lutsk, vul. Taborishi 4

- Museum of Volyn Icon was opened in August 1993. Relatively small museum in the centre on the town. Has some interesting and very old icons. Address: vul. Yaroshchuka 5. (behind the Lesia Ukrainka Volyn State University)

- THE KORSAKS’ MUSEUM OF THE CONTEMPORARY UKRAINIAN ART". Address: vul. Karbysheva 1

Notable people

- Shlomo Ben-Yosef (1913-1938) a member of Revisionist Zionist underground group Irgun.

- Volodymyr Bondar (born 1968), politician, Governor of Volyn Oblast 2005-2007

- Benedykt Chmielowski (1700–1763), a Polish priest, author of encyclopedia, Nowe Ateny

- Count Włodzimierz Czacki (1834–1888) a Polish Cardinal (Catholic Church) from 1882

- Alojzy Feliński (1771-1820), Polish scientist and writer

- Abraham Firkovich (1786–1874) a Karaite writer and Hakham and collector of ancient manuscripts

- Shlomo Flam (died 1813), Hasidic rabbi and maggid in Lutsk

- Kateryna Gornostai (born 1989) a Ukrainian film director, screenwriter and film editor.

- Bolesław Kontrym (1898-1953), a Polish Army officer, participant in the Warsaw Uprising

- Mikołaj Kruszewski (1851-1887), a Polish linguist, co-inventor of the concept of phonemes

- Dinora Pines (1918–2002), British physician and psychoanalyst, especially feminine psychology

- Volodymyr Runchak (born 1960) a Ukrainian accordionist, conductor and composer

- Shmuel Shilo (1929–2011), an Israeli actor, director and producer

- Florian Siwicki (1925-2013), a Polish military officer, diplomat and communist politician.

- Zalman Sorotzkin (1881-1966), an Orthodox rabbi who served as the rabbi of Lutsk and author

- Mordecai Sultansky (ca. 1772-1862), Karaite Jewish hakham and scholar

- Tartak (founded 1994), music band; all members were born in Lutsk

- Shimshon Unichman (1907–1961), Israeli politician and member of the Knesset

- Svitlana Winnikow (1919 -1981), engineer, first woman professor of Mechanical Engineering-Engineering Mechanics at Michigan Technological University

- Oksana Zabuzhko (born 1960), contemporary Ukrainian poet, writer and essayist

- Svetlana Zakharova (born 1979), a Ukrainian prima ballerina with the Bolshoi Ballet

- Joseph Zinker (born 1934), Gestalt psychology therapist, painter and sculptor.

Sport

- Peter Bondra (born 1968), Ukrainian-born Slovak ice hockey player

- Oleksandr Chyzhevskyi (born 1971) football coach and former player with 513 club caps.

- Iurii Kostiuk (born 1977) a Ukrainian biathlete and gold medallist at the Cross-country skiing at the 2006 Winter Paralympics

- Volodymyr Mozolyuk (born 1964) a Ukrainian retired footballer with over 540 club caps.

- Anzhelika Savrayuk (born 1989), Italian rhythmic gymnast, team broze medallist at the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Vyacheslav Shevchuk (born 1979) a retired footballer with 34 club caps and 56 with Ukraine

- Anatoliy Tymoshchuk (born 1979), footballer with 533 club caps and 144 for Ukraine

In popular culture

The NKVD and Nazi massacres are mentioned in the Prix Goncourt awarded novel The Kindly Ones by Jonathan Littell.

Lutsk is a location taken over by post-apocalyptic slavers in the sci-fi/adventure novel The Crisis Pendant by Charlie Patterson.

Twin towns – sister cities

Gallery

-

Volyn' regional administration in Lutsk

-

Kafedralna avenue

-

Modern architecture

-

Dominican monastery

-

Orthodox Fellowship building

-

Daniel of Galicia street

-

Lesya Ukrainka street

References

- ^ a b Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2021 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2021] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

- ^ a b Antoni Tomczyk (2013). "Łuck - Miasto bliskie sercom naszym". Kresowe Stanice. Stowarzyszenie Rodzin Osadników Wojskowych i Cywilnych Kresów Wschodnich. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ Aleksander Gella (1988), Development of Class Structure in Eastern Europe: Poland and Her Southern Neighbors, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-833-1, Google Print, p. 23.

- ^ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998), Poland's Holocaust (Google Books). Jefferson: McFarland, pp. 17-18, 420. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- ^ Feliks Trusiewicz, Zbrodnie – Ludobójstwo dokonane na ludności polskiej w powiecie Łuck, woj. wołyńskie, w latach 1939-1944. (War crimes committed against Polish nationals in the Łuck county, 1939–44). Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Berkhoff, Karel Cornelis (2004). Harvest of Despair. p. 14. ISBN 0674020782. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Piotrowski 1998, p. 17; The Murder of the Jews of Lutsk at Yad Vashem website

- ^ Andrzej Mielcarek, Wieś i kolonia Hnidawa, inaczej Gnidawa, powiat Łuck; Gromada Połonka. Interactive 1936 map included. Strony o Wołyniu Wolyn.ovh.org in Polish. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Yad Vashem, Mass-murder of Łuck Jews at Gurka Polonka in August 1942 on YouTube Note: village Połonka (Template:Lang-pl or its Połonka Little Hill subdivision) is misspelled in the documentary, with testimony of eyewitness Shmuel Shilo. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, Lutsk. Ghetto history. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ "The Holocaust by bullets" by National Geographic Channel on YouTube Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ General Consulate of Poland in Lutsk (Polish and Ukrainian)

- ^ "Police: Armed man holding some 20 people hostage in Ukraine". Associated Press. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Shots heard as bus passengers taken hostage in western Ukraine". Reuters. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Ukraine hostage crisis: Police in Lutsk end stand-off". BBC News. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ www.ukrinform.net 2 killed 6 wounded in attack on airfield in Lutsk

- ^ Sangal, Aditi; Caldwell, Travis; Regan, Helen; Woodyatt, Amy; Chowdhury, Maureen; Kurts, Jason; Snowdon, Kathryn (2022-03-28). "It's 2 p.m. in Kyiv. Here's what you need to know". CNN. No. March 28, 2022 Russia-Ukraine Notices. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2022-04-15. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2022-04-16 suggested (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Побратими Луцька". lutskrada.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Lutsk. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 142.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Official tourist website

- Lutsk - historical description (in Ukrainian)

- Orthodox Lutsk (in Ukrainian)

- Historic images of Lutsk

- Lutsk, Ukraine

- "Photos of Lutsk". photoua.net.

- Lutsk, Ukraine at JewishGen