Alexei Navalny: Difference between revisions

Changing 2017 image to 2020 image |

neutral facial expression |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| native_name = {{nobold|Алексей Навальный}} |

| native_name = {{nobold|Алексей Навальный}} |

||

| native_name_lang = ru |

| native_name_lang = ru |

||

| image = |

| image = Alexey Navalny (cropped) 2.jpg |

||

| image_size = |

| image_size = |

||

| alt = |

| alt = |

||

Revision as of 01:16, 21 September 2022

Alexei Navalny | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Алексей Навальный | ||||||||||

Navalny in 2020 | ||||||||||

| Leader of Russia of the Future[a] | ||||||||||

| Assumed office 17 November 2013 | ||||||||||

| Deputy | Leonid Volkov | |||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | |||||||||

| Founding member of the Anti-Corruption Foundation | ||||||||||

| In office 9 September 2011 – July 2020 | ||||||||||

| Personal details | ||||||||||

| Born | 4 June 1976 Butyn, Odintsovsky District, Moscow Oblast, Soviet Union[1] | |||||||||

| Nationality | Russian | |||||||||

| Political party | Russia of the Future (2013–present) | |||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

| |||||||||

| Spouse | ||||||||||

| Children | 2[2] | |||||||||

| Residence | Moscow | |||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Occupation |

| |||||||||

| Known for | Anti-corruption activism | |||||||||

| Awards |

| |||||||||

| Signature |  | |||||||||

| Website | navalny | |||||||||

YouTube information | ||||||||||

| Channel | ||||||||||

| Subscribers | 6.43 million[3] (3 April 2022) | |||||||||

| Total views | 1.35 billion[3] (3 April 2022) | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

Alexei[b] Anatolievich Navalny (Russian: Алексей Анатольевич Навальный, IPA: [ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej ɐnɐˈtolʲjɪvʲɪtɕ nɐˈvalʲnɨj]; born 4 June 1976) is a Russian opposition leader,[4] lawyer, and anti-corruption activist. He has organised anti-government demonstrations and run for office to advocate reforms against corruption in Russia, and against president Vladimir Putin and his government, who avoids referring directly to Navalny by name.[5] Navalny was a Russian Opposition Coordination Council member. He is the leader of the Russia of the Future party and founder of the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK).[6] He is recognised by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience,[7][8] and was awarded the Sakharov Prize for his work on human rights.[9]

Navalny has more than six million YouTube subscribers;[10] through his social media channels, he and his team have published material about corruption in Russia, organised political demonstrations and promoted his campaigns. In a 2011 radio interview, he described Russia's ruling party, United Russia, as a "party of crooks and thieves," which became a popular epithet.[11] Navalny and the FBK have published investigations detailing alleged corruption by high-ranking Russian officials and their associates.

In July 2013, Navalny received a suspended sentence for embezzlement.[12][13] Despite this, he was allowed to run in the 2013 Moscow mayoral election and came in second, with 27% of the vote, outperforming expectations but losing to incumbent mayor Sergey Sobyanin, a Putin appointee.[14] In December 2014, Navalny received another suspended sentence for embezzlement. Both of his criminal cases were widely considered to be politically motivated and intended to bar him from running in future elections.[15][16] The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) later ruled that the cases violated Navalny's right to a fair trial, but the sentences were never overturned. In December 2016, Navalny launched his presidential campaign for the 2018 presidential election but was barred by Russia's Central Election Commission (CEC) after registering due to his prior criminal conviction; the Russian Supreme Court subsequently rejected his appeal.[15][17][18] In 2017, the documentary He Is Not Dimon to You was released, accusing Dmitry Medvedev, the then prime minister and previous president, of corruption, leading to mass protests.[19] In 2018, Navalny initiated Smart Voting, a tactical voting strategy intended to consolidate the votes of those who oppose United Russia, to the party of seats in elections.[20][21][22]

In August 2020, Navalny was hospitalised in serious condition after being poisoned with a Novichok nerve agent.[23] He was medically evacuated to Berlin and discharged a month later.[24] Navalny accused Putin of being responsible for his poisoning, and an investigation implicated agents from the Federal Security Service.[25][26][27] In January 2021, Navalny returned to Russia and was immediately detained on accusations of violating parole conditions while he was in Germany which were imposed as a result of his 2014 conviction.[28][29][30] Following his arrest and the release of the documentary Putin's Palace, which accused Putin of corruption, mass protests were held across Russia.[31] In February, his suspended sentence was replaced with a prison sentence of over two and half years' detention.[32][33][34] In March 2022, Navalny was sentenced to an additional nine years in prison after being found guilty of embezzlement and contempt of court in a new trial described as a sham by Amnesty International;[35][36] his appeal was rejected and in June, he was transferred to a high-security prison.[37]

Early life and career

Navalny is of Russian and Ukrainian descent.[38][39] His father is from Zalissia, a former village near the Belarus border that was relocated due to the Chernobyl disaster in Ivankiv Raion, Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine. Navalny grew up in Obninsk, about 100 kilometres (62 mi) southwest of Moscow, but spent his childhood summers with his grandmother in Ukraine, acquiring proficiency in the Ukrainian language.[38][40] His parents, Anatoly Navalny and Lyudmila Navalnaya, own a basket-weaving factory, which they have run since 1994, in the village of Kobyakovo, Vologda Oblast.[41]

Navalny graduated from Kalininets secondary school (level 3 according to the ISCED) in 1993.[42] Navalny graduated from the Peoples' Friendship University of Russia in 1998 with a law degree.[43] He then studied securities and exchanges at the Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, graduating in 2001.[44][45] Navalny received a scholarship to the Yale World Fellows program at Yale University in 2010.[46][47]

Since 1998, Navalny worked as a lawyer for various Russian companies.[42] In 2009, Navalny became an advocate and a member of advocate's chamber (bar association) of Kirov Oblast (registration number 43/547). In 2010, due to his move to Moscow, he ceased to be a member of advocate's chamber of Kirov Oblast and became a member of advocate's chamber of Moscow (registration number 77/9991).[48][49] In November 2013, after the judgement in the Kirovles case had entered into force, Navalny was deprived of advocate status.[50]

Political activity

Yabloko

In 2000, following the announcement of a new law that would raise the electoral threshold for State Duma elections, Navalny joined the Russian United Democratic Party Yabloko. According to Navalny, the law was stacked against Yabloko and Union of Right Forces, and he decided to join, even though he was not "a big fan" of either organisation.[51] In 2001, he was listed as a member of the party.[51] In 2002, he was elected to the regional council of the Moscow branch of Yabloko.[52] In 2003, he headed the Moscow subdivision of the election campaign of the party for the parliamentary election held in December. In April 2004, Navalny became Chief of staff of the Moscow branch of Yabloko, which he remained until February 2007. Also in 2004, he became Deputy Chief of the Moscow branch of the party. From 2006 to 2007, he was a member of the Federal Council of the party.[53]

In August 2005, Navalny was incorporated into the Social Council of Central Administrative Okrug of Moscow, created prior to the Moscow City Duma election held later that year, in which he took part as a candidate. In November, he was one of the initiators of the Youth Public Chamber, intended to help younger politicians take part in legislative initiatives.[53] At the same time, in 2005, Navalny started another youth social movement, named "DA! – Democratic Alternative".[c] The project was not connected to Yabloko, nor any other political party. Within the movement, Navalny participated in a number of projects. In particular, he was one of the organisers of the movement-run political debates, which soon resonated in the media.[53] Navalny also organised television debates via state-run Moscow channel TV Center; two initial episodes showed high ratings, but the show was suddenly cancelled. According to Navalny, authorities prohibited some people from receiving TV coverage.[53]

In late 2006, Navalny appealed to the Moscow City Hall, asking it to grant permission to conduct the nationalist 2006 Russian march. However, he added that Yabloko condemned "any ethnic or racial hatred and any xenophobia" and called on the police to oppose "any fascist, Nazi, xenophobic manifestations".[d]

In July 2007, Navalny resigned from the post of Deputy Chief of the Moscow branch of the party.[53] He was consequently expelled from Yabloko for demanding a resignation of the chairman of the party, Grigory Yavlinsky.[55] Also in 2007, Navalny co-founded the National Russian Liberation Movement, known as NAROD (The People), that sets immigration policy as a priority.[56] The movement allied itself with two nationalist groups, the Movement Against Illegal Immigration and Great Russia.[57]

2011 parliamentary election and protests

In December 2011, after parliamentary elections and accusations of electoral fraud,[58] approximately 6,000 people gathered in Moscow to protest the contested result, and an estimated 300 people were arrested, including Navalny. Navalny was arrested on 5 December.[59][60] After a period of uncertainty for his supporters, Navalny appeared in court and was sentenced to the maximum 15 days "for defying a government official". Alexei Venediktov, editor-in-chief of Echo of Moscow radio station, called the arrest "a political mistake: jailing Navalny transforms him from an online leader into an offline one".[60] After his arrest, his blog became available in English.[59] Navalny was kept in the same prison as several other activists, including Ilya Yashin and Sergei Udaltsov, the unofficial leader of the Vanguard of Red Youth, a radical Russian communist youth group. Udaltsov went on a hunger strike to protest against the conditions.[61]

Upon his release on 20 December, Navalny called on Russians to unite against Putin, who Navalny said would try to claim victory in the presidential election, which was held on 4 March 2012.[62] In a profile published the day after his release, BBC News described Navalny as "arguably the only major opposition figure to emerge in Russia in the past five years".[63]

After his release, Navalny informed reporters that it would be senseless for him to run in the presidential elections because the Kremlin would not allow the elections to be fair. But he said that if free elections were held, he would "be ready" to run.[62] On 24 December, he helped lead a demonstration, estimated at 50,000 people, which was much larger than the previous post-election demonstration. Speaking to the crowd, he said, "I see enough people to take the Kremlin right now".[64]

In March 2012, after Putin was elected president, Navalny helped lead an anti-Putin rally in Moscow's Pushkinskaya Square, attended by between 14,000 and 20,000 people. After the rally, Navalny was detained by authorities for several hours, then released.[65] On 8 May, the day after Putin was inaugurated, Navalny and Udaltsov were arrested after an anti-Putin rally at Clean Ponds, and were each given 15-day jail sentences.[66] Amnesty International designated the two men prisoners of conscience.[67] On 11 June, Moscow prosecutors conducted a 12-hour search of Navalny's home, office, and the apartment of one of his relatives.[68] Soon afterwards, some of Navalny's personal emails were posted online by a pro-government blogger.[69]

New party

On 26 June 2012, it was announced that Navalny's comrades would establish a new political party based on e-democracy; Navalny declared he did not plan to participate in this project at the moment.[70] On 31 July, they filed a document to register an organising committee of a future party named "The People's Alliance".[71] The party identified itself as centrist; one of the then-current leaders of the party, and Navalny's ally Vladimir Ashurkov, explained this was intended to help the party get a large share of voters. Navalny said the concept of political parties was "outdated", and added his participation would make maintaining the party more difficult. However, he "blessed" the party and discussed its maintenance with its leaders. They, in turn, stated they wanted to eventually see Navalny as a member of the party.[72] On 15 December, Navalny expressed his support of the party, saying, "The People's Alliance is my party", but again refused to join it, citing the criminal cases against him.[73]

On 10 April 2013, the party filed documents for the official registration of the party.[74] On 30 April, the registration of the party was suspended.[75] On 5 July, the party was declined registration; according to Izvestia, not all founders of the party were present during the congress, even though the papers contained their signatures.[76] Navalny reacted to that with a tweet saying, "[…] A salvo of all guns".[77] Following the mayoral election, on 15 September, Navalny declared he would join and, possibly, head the party.[78] On 17 November Navalny was elected as the leader of the party.[79]

On 8 January 2014, Navalny's party filed documents for registration for the second time.[80] On 20 January, registration of the party was suspended;[81] according to Russian laws, no two parties can share a name.[82] On 8 February, Navalny's party changed its name to "Progress Party".[83] On 25 February, the party was registered, and[84] at this point, had six months to register regional branches in at least half of the federal subjects of Russia.[e] On 26 September, the party declared it had registered 43 regional branches.[86] An unnamed source of Izvestia in the ministry said registrations completed after the six-month term would not be taken into consideration, adding, "Yes, trials are taking place in some regions […] they cannot register new branches in other regions during the trials, because the main term is over". Navalny's blog countered, "Our answer is simple. A six-month term for registration has been legally prolonged ad interim prosecution of appeals of denials and registration suspensions".[86]

On 1 February 2015, the party held a convention, where Navalny stated the party was preparing for the 2016 elections, declaring the party would maintain its activity across Russia, saying, "We are unabashed to work in remote lands where the opposition does not work. We can even [work] in Crimea". The candidates the party would appoint were to be chosen via primary elections; however, he added, the party's candidates may be removed from elections.[87] On 17 April, the party initiated a coalition of democratic parties.[88] On 28 April, the party was deprived of registration by the Ministry of Justice, which stated the party had not registered the required number of regional branches within six months after the official registration.[89] Krainev claimed that the party could be eliminated only by the Supreme Court, and he added that not all trials of registration of regional branches were over, calling the verdict "illegal twice". He added that the party would appeal to the European Court of Human Rights, and expressed confidence that the party would be restored and admitted to elections.[90] The next day, the party officially challenged the verdict.[91]

2013 Moscow mayoral candidacy

| Time | Sobyanin | Navalny | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 29 August–2 September | 60.1% | 21.9% | [92] |

| 22–28 August | 63.9% | 19.8% | [93] |

| 15–21 August | 62.5% | 20.3% | [94] |

| 8–14 August | 63.5% | 19.9% | [95] |

| 1–7 August | 74.6% | 15.0% | [95] |

| 25–31 July | 76.2% | 16.7% | [96] |

| 18–24 July | 76.6% | 15.7% | [97] |

| 11–16 July | 76.2% | 14.4% | [98] |

| 4–10 July | 78.5% | 10.7% | [98] |

| 27 June–3 July | 77.9% | 10.8% | [98] |

On 30 May 2013, Sergey Sobyanin, the mayor of Moscow, argued an elected mayor is an advantage for the city compared to an appointed one,[99] and on 4 June, he announced he would meet President Vladimir Putin and ask him for a snap election, mentioning the Muscovites would agree the governor elections should take place in the city of Moscow and the surrounding Moscow Oblast simultaneously.[100] On 6 June, the request was granted,[101] and the next day, the Moscow City Duma appointed the election on 8 September, the national voting day.[102]

On 3 June, Navalny announced he would run for the post.[103] To become an official candidate, he would need either seventy thousand signatures of Muscovites or to be pegged for the office by a registered party, and then to collect 110 signatures of municipal deputies from 110 different subdivisions (three-quarters of Moscow's 146). Navalny chose to be pegged by a party, RPR–PARNAS.[104]

Among the six candidates who were officially registered as such, only two (Sobyanin and Communist Ivan Melnikov) were able to collect the required number of the signatures themselves, and the other four were given a number of signatures by the Council of Municipal Formations, following a recommendation by Sobyanin,[105] to overcome the requirement (Navalny accepted 49 signatures, and other candidates accepted 70, 70, and 82).[106]

On 17 July, Navalny was registered as one of the six candidates for the Moscow mayoral election.[107] However, on 18 July, he was sentenced to a five-year prison term for the embezzlement and fraud charges that were declared in 2012. Several hours after his sentencing, he pulled out of the race and called for a boycott of the election.[108] However, later that day, the prosecution office requested the accused should be freed on bail and released from travel restrictions, since the verdict had not yet taken legal effect, saying that the accused had previously followed the restrictions. Navalny was a mayoral candidate, and an imprisonment would thus not comply with his rule for equal access to the electorate.[109] On his return to Moscow after being freed, pending an appeal, he vowed to stay in the race.[110] The Washington Post has speculated that his release was ordered by the Kremlin in order to make the election and Sobyanin appear more legitimate.[14]

Navalny's campaign was successful in fundraising: out of 103.4 million rubles (approximately $3.09 million as of the election day[rates 1]), the total size of his electoral fund, 97.3 million ($2.91 million) were transferred by individuals throughout Russia;[112] such an amount is unprecedented in Russia.[113] It achieved a high profile through an unprecedentedly large campaign organisation that involved around 20,000 volunteers who passed out leaflets and hung banners, in addition to conducting several campaign rallies a day around the city;[114] they were the main driving force for the campaign.[115] The New Yorker described the resulted campaign as "a miracle", along with Navalny's release on 19 July, the fundraising campaign, and the personality of Navalny himself.[116] The campaign received very little television coverage and did not utilise billboards. Thanks to Navalny's strong campaign (and Sobyanin's weak one[114]), his result grew over time, weakening Sobyanin's, and in the end of the campaign, he declared the runoff election (to be conducted if none of the candidates receives at least 50% of votes) was "a hair's breadth away".

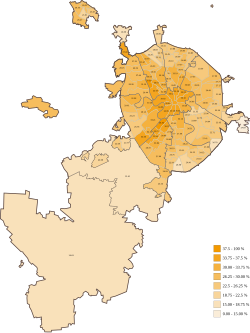

The largest sociological research organisations predicted that Sobyanin would win the election, scoring 58% to 64% of the vote; they expected Navalny to receive 15–20% of the vote, and the turnout was to be 45–52%. (Levada Center was the only one not to have made any predictions; the data it had on 28 August, however, falls in line with other organisations.)[117] The final results of the voting showed Navalny received 27% of the vote, more than candidates appointed by the parties that received second, third, fourth, and fifth highest results during the 2011 parliamentary elections, altogether. Navalny fared better in the center and southwest of Moscow, which have higher income and education levels.[14] However, Sobyanin received 51% of the vote, which meant he won the election. The turnout was 32%.[118] The organisations explained the differences were because Sobyanin's electorate did not vote, as they felt that their candidate was guaranteed to win. Navalny's campaign office predicted Sobyanin would score 49–51%, and Navalny would get 24–26% of votes.[117]

Many experts said the election had been fair, that the number of irregularities had been much lower than those of other elections held within the country, and that the irregularities had had little effect on the result.[119][120] Dmitri Abyzalov, leading expert of Center of Political Conjuncture, added low turnout figures provide a further sign of fairness of the election, because that shows they were not overestimated.[119] However, according to Andrei Buzin, co-chairman of the GOLOS Association, State Departments of Social Security added people who did not originally want to vote to lists of those who would vote at home, with the number of such voters being 5% of those who voted, and added this did cause questions if Sobyanin would score 50% if this did not take place.[120] Dmitry Oreshkin, leader of the "People's election commission" project (who did a separate counting based on the data from election observers; their result for Sobyanin was 50%), said now that the runoff election was only 2% away, all details would be looked at very closely, and added it was impossible to prove "anything" juridically.[121]

On 9 September, the day following the election, Navalny publicly denounced the tally, saying, "We do not recognise the results. They are fake". Sobyanin's office rejected an offer of a vote recount.[122] On 12 September, Navalny addressed the Moscow City Court to overturn the result of the poll; the court rejected the assertion. Navalny then challenged the decision in the Supreme Court of Russia, but the court ruled that the election results were legitimate.[123]

RPR-PARNAS and democratic coalition

Following the mayoral election, Navalny was offered a position as the fourth co-chairman of RPR-PARNAS.[124] However, Navalny made no public reaction.[citation needed]

On 14 November 2014, the two remaining RPR-PARNAS co-chairmen, Boris Nemtsov and former Prime Minister of Russia Mikhail Kasyanov, declared it was the right moment to create a wide coalition of political forces, who favour the "European choice"; Navalny's Progress Party was seen as one of the potential participants.[125] However, on 27 February 2015, Nemtsov was shot dead. Prior to his assassination, Nemtsov worked on a project of a coalition, in which Navalny and Khodorkovsky would become co-chairmen of RPR-PARNAS. Navalny declared merging parties would invoke bureaucratic difficulties and question the legitimacy of party's right to participate in federal elections without signatures collecting.[126] However, Nemtsov's murder accelerated the work, and on 17 April, Navalny declared a wide discussion had taken place among Progress Party, RPR-PARNAS, and other closely aligned parties, which resulted in an agreement of formation of a new electoral bloc between the two leaders.[88] Soon thereafter, it was signed by four other parties and supported by Khodorkovsky's Open Russia foundation.[127] Electoral blocs are not present within the current[when?] law system of Russia, so it would be realised via means of a single party, RPR-PARNAS, which is not only eligible for participation in statewide elections, but is also currently[when?] not required to collect citizens' signatures for the right to participate in the State Duma elections scheduled for September 2016, due to the regional parliament mandate previously taken by Nemtsov. The candidates RPR-PARNAS would appoint were to be chosen via primary elections.[128]

On 5 July 2015, Kasyanov was elected as the only leader of RPR-PARNAS, and the party was renamed to just PARNAS. He added he would like to eventually re-establish the institution of co-chairmanship, adding, "Neither Alexei Navalny nor Mikhail Khodorkovsky will enter our party today and be elected as co-chairmen. But in the future, I think, such time will come".[129] On 7 July, in an interview released by TV Rain, he specified Navalny could not leave a party of his, and this would need to be completed by PARNAS adsorbing members of the Progress Party and other parties of the coalition, and Navalny would be to come at some point when he "grows into this and feels this could be done" and join the party as well.[130]

The coalition claimed to have collected enough citizens' signatures for registration in the four regions it originally aimed for. However, in one region, the coalition would declare some signatures and personal data have been altered by malevolent collectors;[131] signatures in the other regions have been rejected by regional election commissions.[132][133][134] In Novosibirsk Oblast, some election office stuff went for a hunger strike, which was abandoned after in almost two weeks since its inception, when Khodorkovsky, Navalny, and Kasyanov publicly advised to do so.[135] Сomplaints have been issued to the Central Election Commission of Russia, after which the coalition has been registered as a participant in a regional election in one of the three contested regions, Kostroma Oblast. According to a source of Gazeta.ru "close to the Kremlin", the presidential administration saw coalition's chances as very low, yet was wary, but the restoration in one region occurred so PARNAS could "score a consolation goal".[136] According to the official election results, the coalition scored 2% of votes, not enough to overcome the 5% threshold; the party admitted the election was lost.[137]

2018 presidential election

Navalny announced his entry into the presidential race on 13 December 2016,[138][139] however on 8 February 2017, the Leninsky district court of Kirov repeated its sentence of 2013 (which was previously annulled after the decision of ECHR, which ruled that Russia had violated Navalny's right to a fair trial, in the Kirovles case) and charged him with a five-year suspended sentence.[140] This sentence, if it came into force and remained valid, might prohibit the future official registration of Navalny as a candidate. Navalny announced that he would pursue the annulment of the sentence that clearly contradicts the decision of ECHR. Moreover, Navalny announced that his presidential campaign would proceed independently of court decisions. He referred to the Russian Constitution (Article 32), which deprives only two groups of citizens of the right to be elected: those recognised by the court as legally unfit and those kept in places of confinement by a court sentence. According to Freedom House and The Economist, Navalny was the most viable contender to Vladimir Putin in the 2018 election.[15][141] Navalny organised a series of anti-corruption rallies in different cities across Russia in March. This appeal was responded to by the representatives of 95 Russian cities, and four cities abroad: London, Prague, Basel and Bonn.[142]

Navalny was attacked by unknown assailants outside his office in the Anti-Corruption Foundation on 27 April 2017. They sprayed brilliant green dye, possibly mixed with other components, into his face in a Zelyonka attack that can damage eyes of the victim. He had been attacked before, earlier in the spring. In the second attack, the green-colored disinfectant had evidently been mixed with a caustic chemical, resulting in a chemical burn to his right eye.[143] He reportedly lost 80 percent of the sight in his right eye.[144][145] Navalny accused the Kremlin of orchestrating the attack.[146][147]

Navalny was released from jail on 27 July 2017 after spending 25 days of imprisonment. Before that, he was arrested in Moscow for participating in protests and was sentenced to 30 days in jail for organising illegal protests.[148]

In September, Human Rights Watch accused Russian police of systematic interference with Navalny's presidential campaign. "The pattern of harassment and intimidation against Navalny's campaign is undeniable," said Hugh Williamson, Europe, and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. "Russian authorities should let Navalny's campaigners work without undue interference and properly investigate attacks against them by ultra-nationalists and pro-government groups."[149] On 21 September, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe invited Russian authorities, in connection with the Kirovles case, "to use urgently further avenues to erase the prohibition on Mr. Navalny's standing for election".[150]

Navalny was sentenced to 20 days in jail on 2 October 2017 for calls to participate in protests without approval from state authorities.[151]

In December 2017, Russia's Central Electoral Commission barred Navalny from running for president in 2018, citing Navalny's corruption conviction. The European Union said Navalny's removal cast "serious doubt" on the election. Navalny called for a boycott of the 2018 presidential election, stating his removal meant that millions of Russians were being denied their vote.[18] Navalny filed an appeal against the Russian Supreme Court's ruling on 3 January,[152] however a few days later on 6 January, the Supreme Court of Russia rejected his appeal.[153] Navalny led protests on 28 January 2018 to urge a boycott of Russia's 2018 presidential election. Navalny was arrested on the day of the protest and then released the same day, pending trial. OVD-Info reported that 257 people were arrested throughout the country. According to Russian news reports, police stated Navalny was likely to be charged with calling for unauthorised demonstrations.[154] Two of Navalny's associates were given brief jail terms for urging people to attend unsanctioned opposition rallies. Navalny stated on 5 February 2018 the government was accusing Navalny of assaulting an officer during the protests.[155] Navalny was among 1600 people detained during 5 May protests prior to Putin's inauguration; Navalny was charged with disobeying police.[156] On 15 May, he was sentenced to 30 days in jail.[157] Immediately after his release on 25 September 2018, he was arrested and convicted for organising illegal demonstrations and sentenced to another 20 days in jail.

2019 Moscow City Duma elections

During the 2019 Moscow City Duma election Navalny supported independent candidates, most of whom were not allowed to participate in the elections, which led to mass street protests. In July 2019, Navalny was arrested, first for ten days, and then, almost immediately, for 30 days. On the evening of 28 July, he was hospitalised with severe damage to his eyes and skin. At the hospital, he was diagnosed with an "allergy," although this diagnosis was disputed by Anastasia Vasilieva, an ophthalmologist who previously treated Navalny after a chemical attack by an alleged protester in 2017.[158] Vasilieva questioned the diagnosis and suggested the possibility that Navalny's condition was the result of "the damaging effects of undetermined chemicals".[159] On 29 July 2019, Navalny was discharged from hospital and taken back to prison, despite the objections of his personal physician who questioned the hospital's motives.[158][160] Supporters of Navalny and journalists near the hospital were attacked by the police and many were detained.[159] In response, he initiated the Smart Voting project.

2020 constitutional referendum

Navalny campaigned against the vote on constitutional amendments that took place on 1 July, calling it a "coup" and a "violation of the constitution".[23] He also said that the changes would allow President Putin to become "president for life".[161][162] After the results were announced, he called them a "big lie" that did not reflect public opinion.[163] The reforms include an amendment allowing Putin to serve another two terms in office (until 2036), after his fourth presidential term ends.[23]

Anti-corruption investigations

In 2008, Navalny invested 300,000 rubles in stocks of 5 oil and gas companies: Rosneft, Gazprom, Gazprom Neft, Lukoil, and Surgutneftegas, thus becoming an activist shareholder.[51] As such, he began to aim at making the financial assets of these companies transparent. This is required by law, but there are allegations that high-level managers of these companies are involved in theft and resisting transparency.[164] Other activities deal with wrongdoings by Russian police, such as Sergei Magnitsky's case.

In November 2010, Navalny published[165] confidential documents about Transneft's auditing. According to Navalny's blog, about 4 billion dollars were stolen by Transneft's leaders during the construction of the Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean oil pipeline.[166][167] In December, Navalny announced the launch of the RosPil project, which seeks to bring to light corrupt practices in the government procurement process.[168] The project takes advantage of existing procurement regulation that requires all government requests for tender to be posted online. Information about winning bids must be posted online as well. The name RosPil is a pun on the slang term "raspil" (wikt:ru:распил) (literally "sawing"),[169] implying the embezzlement of state funds.

In May 2011, Navalny launched RosYama (literally "Russian Hole"), a project that allowed individuals to report potholes and track government responses to complaints.[170] In August, Navalny published papers related to a scandalous real estate deal[171] between the Hungarian and Russian governments.[172][173] According to the papers, Hungary sold a former embassy building in Moscow for US$21 million to an offshore company of Viktor Vekselberg, who immediately resold it to the Russian government for US$116 million. Irregularities in the paper trail implied collusion. Three Hungarian officials responsible for the deal were detained in February 2011.[174] It is unclear whether any official investigation was conducted on the Russian side.

In February 2012, Navalny concluded that Russian federal money going to Ramzan Kadyrov's Chechen Interior Ministry was being spent "in a totally shadowy and fraudulent way."[175] In May, Navalny accused Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov of corruption, stating that companies owned by Roman Abramovich and Alisher Usmanov had transferred tens of millions of dollars to Shuvalov's company, allowing Shuvalov to share in the profit from Usmanov's purchase of the British steel company Corus. Navalny posted scans of documents to his blog showing the money transfers.[176] Usmanov and Shuvalov stated the documents Navalny had posted were legitimate, but that the transaction had not violated Russian law. "I unswervingly followed the rules and principles of conflict of interest," said Shuvalov. "For a lawyer, this is sacred".[177] In July, Navalny posted documents on his blog allegedly showing that Alexander Bastrykin, head of the Investigative Committee of Russia, owned an undeclared business in the Czech Republic. The posting was described by the Financial Times as Navalny's "answering shot" for having had his emails leaked during his arrest in the previous month.[69]

In August 2018, Navalny alleged that Viktor Zolotov stole at least US$29 million from procurement contracts for the National Guard of Russia. Shortly after his allegations against Zolotov, Navalny was imprisoned for staging protests in January 2018. Subsequently, Viktor Zolotov published a video message on 11 September challenging Navalny to a duel and promising to make "good, juicy mincemeat" of him.[179][180]

Medvedev

In March 2017, Navalny published the investigation He Is Not Dimon to You, accusing Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev of corruption. The authorities either ignored the accusation or argued that it was made by a "convicted criminal" and not worth comment. On 26 March, Navalny organised a series of anti-corruption rallies in cities across Russia. In some cities, the rallies were sanctioned by authorities, but in others, including Moscow and Saint Petersburg, they were not allowed. The Moscow police said that 500 people had been detained, but according to the human-rights group OVD-Info, 1,030 people were detained in Moscow alone, including Navalny himself.[181][182] On 27 March, he was fined 20,000 rubles minimum for organising an illegal protest, and jailed for 15 days for resisting arrest.[183]

Putin

On 19 January 2021, two days after he was detained by Russian authorities upon his return to Russia, an investigation by Navalny and the FBK was published accusing President Vladimir Putin of using fraudulently obtained funds to build a massive estate for himself near the town of Gelendzhik in Krasnodar Krai, in what he called "the world's biggest bribe". The estate was first reported on in 2010 after the businessman Sergei Kolesnikov, who was involved in the project, gave details about it. According to Navalny, the estate is 39 times the size of Monaco, with the Federal Security Service (FSB) owning 70 square kilometers of land around the palace, and the estate cost over 100 billion rubles ($1.35 billion) to construct.[184] It also showed aerial footage of the estate via a drone, and a detailed floorplan of the palace that Navalny and the FBK said was given by a contractor, which was compared to photographs from inside the palace that were leaked onto the Internet in 2011. Using the floorplan, computer-generated visualisations of the palace interior were also shown.[31]

There are impregnable fences, its own port, its own security, a church, its own permit system, a no-fly zone, and even its own border checkpoint. It is absolutely a separate state within Russia.[31]

— Alexei Anatolievich Navalny

This investigation also detailed an elaborate corruption scheme allegedly involving Putin's inner circle that allowed Putin to hide billions of dollars to build the estate. Navalny's team also said that it managed to confirm reporting about Putin's alleged lovers Svetlana Krivonogikh and Alina Kabaeva.[31][185][186][187] Navalny's video on YouTube garnered over 20 million views in less than a day, and over 92 million after a week. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov in a press conference called the investigation a "scam" and said that citizens should "think before transferring money to such crooks".[188]

Putin denied ownership of the palace and the oligarch Arkady Rotenberg claimed ownership.[189][190]

Criminal cases

Kirovles case

Case

On 30 July 2012, the Investigative Committee charged Navalny with embezzlement. The committee stated that he had conspired to steal timber from Kirovles, a state-owned company in Kirov Oblast, in 2009, while acting as an adviser to Kirov's governor Nikita Belykh.[177][191] Investigators had closed a previous probe into the claims for lack of evidence.[192] Navalny was released on his own recognizance but instructed not to leave Moscow.[193]

Navalny described the charges as "weird" and unfounded.[192] He stated that authorities "are doing it to watch the reaction of the protest movement and of Western public opinion […] So far they consider both of these things acceptable and so they are continuing along this line".[177] His supporters protested before the Investigative Committee offices.[191]

In April 2013 Loeb & Loeb LLP[f] issued "An Analysis of the Russian Federation's prosecutions of Alexei Navalny", a paper detailing Investigative Committee accusations. The paper concludes that "the Kremlin has reverted to misuse of the Russian legal system to harass, isolate and attempt to silence political opponents".[194][195]

Conviction and release

The Kirovles trial commenced in the city of Kirov on 17 April 2013.[196] On 18 July, Navalny was sentenced to five years in jail for embezzlement.[12] He was found guilty of misappropriating about 16 million rubles'[197] ($500,000) worth of lumber from a state-owned company.[198] The sentence read by the judge Sergey Blinov was textually the same as the request of the prosecutor, with the only exception that Navalny was given five years, and the prosecution requested six years.[199]

Later that evening, the Prosecutor's Office appealed Navalny and Ofitserov jail sentences, arguing that until the higher court affirmed the sentence, the sentence was invalid. The next morning, the appeal was granted. Navalny and Ofitserov were released on 19 July, awaiting the hearings of the higher court.[200] The prosecutor's requested decision was described as "unprecedented" by experts.[who?][201]

Probation

The prison sentence was suspended by a court in Kirov on 16 October 2013, still being a burden for his political future.[202]

Review of the sentence

On 23 February 2016 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Russia had violated Navalny's right to a fair trial, and ordered the government to pay him 56,000 euros in legal costs and damages.[203]

On 16 November 2016 Russia's Supreme Court overturned the 2013 sentence, sending the verdict back to the Leninsky District Court in Kirov for review.[204]

On 8 February 2017 the Leninsky district court of Kirov repeated its sentence of 2013 and charged Navalny with a five-year suspended sentence.[140] Navalny announced that he will pursue the annulment of the sentence that clearly contradicts the decision of ECHR.[205][206]

Yves Rocher case and home arrest

Case

In 2008 Oleg Navalny made an offer to Yves Rocher Vostok, the Eastern European subsidiary of Yves Rocher between 2008 and 2012, to accredit Glavpodpiska, which was created by Navalny, with delivering duties. On 5 August, the parties signed a contract. To fulfill the obligations under the agreement, Glavpodpiska outsourced the task to sub-suppliers, AvtoSAGA and Multiprofile Processing Company (MPC). In November and December 2012, the Investigating Committee interrogated and questioned Yves Rocher Vostok. On 10 December, Bruno Leproux, general director of Yves Rocher Vostok, filed to the Investigative Committee, asking to investigate if the Glavpodpiska subscription company had damaged Yves Rocher Vostok, and the Investigative Committee initiated a case.[207]

The prosecution claimed Glavpodpiska embezzled money by taking duties and then redistributing them to other companies for lesser amounts of money, and collecting the surplus: 26.7 million rubles ($540,000) from Yves Rocher Vostok, and 4.4 million rubles from the MPC. The funds were claimed to be subsequently legalised by transferring them on fictitious grounds from a fly-by-night company to Kobyakovskaya Fabrika Po Lozopleteniyu, a willow weaving company founded by Navalny and operated by his parents.[208][209][210] Navalnys denied the charges. The brothers' lawyers claimed, the investigators "added phrases like 'bearing criminal intentions' to a description of regular entrepreneurial activity". According to Oleg Navalny's lawyer, Glavpodpiska did not just collect money, it controlled provision of means of transport, execution of orders, collected and expedited production to the carriers, and was responsible before clients for terms and quality of executing orders.[207]

Yves Rocher denied that they had any losses, as did the rest of the witnesses, except the Multiprofile Processing Company CEO Sergei Shustov, who said he had learned about his losses from an investigator and believed him, without making audits. Both brothers and their lawyers claimed Alexei Navalny did not participate in the Glavpodpiska operations, and witnesses all stated they had never encountered Alexei Navalny in person before the trial.[207]

Home arrest and limitations

Following the imputed violation of travel restrictions, Navalny was placed under house arrest and prohibited from communicating with anyone other than his family, lawyers, and investigators on 28 February 2014.[211][212] Navalny claimed the arrest was politically motivated, and he filed a complaint to the European Court of Human Rights. On 7 July, he declared the complaint had been accepted and given priority; the court compelled the Government of Russia to provide answers to a questionnaire.

The home arrest, in particular, prohibited usage of the internet; however, new posts were released under his social media accounts after the arrest was announced. A 5 March post claimed the accounts were controlled by his Anti-Corruption Foundation teammates and his wife Yulia. On 13 March his LiveJournal blog was blocked in Russia, because, according to the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor), "functioning of the given web page breaks the regulation of the juridical decision of the bail hearing of a citizen against whom a criminal case has been initiated".[213] Navalny's associates started a new blog, navalny.com, and the LiveJournal blog was eventually abolished, with the last post published on 9 July.

The home arrest was eased a number of times: On 21 August Navalny was allowed to communicate with his co-defendants;[214] a journalist present in the courthouse at the moment confirmed Navalny was allowed to communicate with "anyone but the Yves Rocher case witnesses".[215] On 10 October, his right to communicate with the press was confirmed by another court, and he was allowed to make comments on the case in media (Navalny's plea not to prolong the arrest was, however, rejected).[216] On 19 December, he was allowed to mail correspondence to authorities and international courts. Navalny again pleaded not to prolong the arrest, but the plea was rejected again.[217]

Conviction

The verdict was announced on 30 December 2014. Both brothers were found guilty of fraud against MPK and Yves Rocher Vostok and money laundering, and were convicted under Articles 159.4 §§ 2 and 3 and 174.1 § 2 (a) and (b) of the Criminal Code.[218] Alexei Navalny was given 31⁄2 years of suspended sentence, and Oleg Navalny was sentenced to 31⁄2 years in prison and was arrested after the verdict was announced;[219] both had to pay a fine of 500,000 rubles and a compensation to the Multiprofile Processing Company (MPK) of over 4 million rubles.[220] In the evening, several thousand protesters gathered in the center of Moscow. Navalny broke his home arrest to attend the rally and was immediately arrested by the police and brought back home.[221]

Both brothers filed complaints to the European Court of Human Rights: Oleg's was communicated and given priority; Alexei's was reviewed in the context of the previous complaint related to this case and the Government of Russia had been "invited to submit further observations".[222] The second instance within the country confirmed the verdict, only releasing Alexei from the responsibility to pay his fine. Both prosecutors and defendants were not satisfied with this decision.[220]

ECHR

On 17 October 2017 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Navalny's conviction for fraud and money laundering "was based on an unforeseeable application of criminal law and that the proceedings were arbitrary and unfair." The Court found that the domestic court's decisions had been arbitrary and manifestly unreasonable. ECHR found the Russian courts' decisions violated articles 6 and 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights.[223][224] On 15 November 2018, the Grand Chamber upheld the decision.[225]

Indemnification

After the Yves Rocher case, Navalny had to pay a compensation of 4.4 million rubles. He declared the case was "a frame up", but he added he would pay the sum as this could affect granting his brother's parole.[226] On 7 October 2015, Alexei's lawyer announced the defendant willingly paid 2.9 million and requested an installment plan for the rest of the sum.[227] The request was granted, except the term was contracted from the requested five months to two,[228] and a part of the sum declared paid (900,000 rubles; arrested from Navalny's banking account) was not yet received by the police; the prosecutors declared that may happen because of inter-process delays.[229]

Later that month, Kirovles sued Navalny for the 16.1 million rubles' declared pecuniary injury; Navalny declared he had not expected the suit, as Kirovles did not initiate it during the 2012–2013 trial.[230] On 23 October, a court resolved the said sum should be paid by the three defendants.[230] The court denied the defendants' motion 14.7 million had already been paid by that point; the verdict and the payment sum were justified by a ruling by a Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation.[231] Navalny declared he could not cover the requested sum; he called the suit a "drain-dry strategy" by authorities.[230]

Other cases

In late December 2012 Russia's federal Investigative Committee asserted that Allekt, an advertising company headed by Navalny, defrauded the Union of Right Forces (SPS) political party in 2007 by taking 100 million rubles ($3.2 million) payment for advertising and failing to honor its contract. If charged and convicted, Navalny could be jailed for up to 10 years. "Nothing of the sort happened—he committed no robbery", Leonid Gozman, a former SPS official, was quoted as saying. Earlier in December, "the Investigative Committee charged […] Navalny and his brother Oleg with embezzling 55 million rubles ($1.76 million) in 2008–2011 while working in a postal business". Navalny, who denied the allegations in the two previous cases, sought to laugh off news of the third inquiry with a tweet stating "Fiddlesticks […]".[232]

In April 2020, Yandex search engine started artificially placing negative commentary about Navalny on the top positions in its search results for his name.[233] Yandex declared this was part of an "experiment" and returned to presenting organic search results.[234][235][236]

Navalny alleged that Russian billionaire and businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin was linked to a company called Moskovsky Shkolnik (Moscow schoolboy) that had supplied poor quality food to schools which had caused a dysentery outbreak.[237][238] In April 2019, Moskovsky Shkolnik filed a lawsuit against Navalny. In October 2019, the Moscow Arbitration Court ordered Navalny to pay 29.2 million rubles. Navalny said that "Cases of dysentery were proven using documents. But it's us that has to pay."[239] Prigozhin was quoted by the press service of his catering company Concord Management and Consulting on 25 August 2020 as saying that he intended to enforce a court decision that required Navalny, his associate Lyubov Sobol and his Anti-Corruption Foundation to pay 88 million rubles in damages to the Moskovsky Shkolnik company over a video investigation.[240]

By 2019 Navalny had won six complaints against Russian authorities in the ECHR for a total of €225,000.[241]

Poisoning and recovery

On 20 August 2020 Navalny fell ill during a flight from Tomsk to Moscow and was hospitalised in the Emergency City Clinical Hospital No. 1 in Omsk (Городская клиническая больница скорой медицинской помощи №1), where the plane had made an emergency landing. The change in his condition on the plane was sudden and violent, and video footage showed crewmembers on the flight scurrying towards him as he screamed loudly.[242] Later, he said that he was not screaming from pain, but from the knowledge that he was dying.[243]

Afterwards, his spokeswoman, Kira Yarmysh, said that he was in a coma and on a ventilator in the Omsk hospital. She also said that since he arose that morning, Navalny had consumed nothing but a cup of tea, acquired at the airport. It was initially suspected that something was mixed into his drink, and physicians stated that a "toxin mixed into a hot drink would be rapidly absorbed". The hospital said that he was in a stable but serious condition. Although staff initially acknowledged that Navalny had probably been poisoned, after numerous police personnel appeared outside Navalny's room, the medical staff was less forthcoming. The Omsk hospital's deputy chief physician later told reporters that poisoning was "one scenario among many" being considered.[242]

A plane was sent from Germany to evacuate Navalny from Russia for treatment at the Charité Hospital in Berlin, even though the doctors treating him in Omsk initially declared he was too sick to be transported,[244] they later released him.[245][246] On 24 August, the doctors in Germany made an announcement, confirming that Navalny had been poisoned with a cholinesterase inhibitor.[247]

Ivan Zhdanov, chief of Navalny's Anti-Corruption Foundation, said that Navalny could have been poisoned because of one of the foundation's investigations.[237] On 2 September, the German government announced that Navalny was poisoned with a Novichok nerve agent, from the same family of nerve agents that was used to poison Sergei Skripal and his daughter. International officials said that they had obtained "unequivocal proof" from toxicology tests, and have called on the Russian government for an explanation.[248][249][250] On 7 September, German doctors announced that he was out of the coma.[251] On 15 September, Navalny's spokeswoman said that Navalny would return to Russia.[252] On 17 September, Navalny's team said that traces of the nerve agent used to poison Navalny was detected on an empty water bottle from his hotel room in Tomsk, suggesting that he was possibly poisoned before leaving the hotel.[253] On 23 September, Navalny was discharged from hospital after his condition had sufficiently improved.[254] On 6 October OPCW confirmed presence of cholinesterase inhibitor from the Novichok group in Navalny's blood and urine samples.[255][256][257]

On 14 December a joint investigation by The Insider and Bellingcat in co-operation with CNN and Der Spiegel was published, which implicated agents from Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) in Navalny's poisoning. The investigation detailed a special unit of the FSB, which specialises in chemical substances, and the investigators then tracked members of the unit, using telecom and travel data. According to the investigation, Navalny was under surveillance by a group of operatives from the unit for 3 years and there may have been earlier attempts to poison Navalny.[258][259][260][261] In an interview with Spanish newspaper El País, Navalny said that "It is difficult for me to understand exactly what is going on in [Putin's] mind. … 20 years of power would spoil anyone and make them crazy. He thinks he can do whatever he wants."[262]

On 21 December 2020 Navalny released a video showing him impersonating a Russian security official and speaking over the phone with a man identified by some investigative news media as a chemical weapons expert named Konstantin Kudryavtsev. During the call, he revealed that the poison had been placed on Navalny's clothing, particularly in his underwear, and that Navalny would have died if not for the plane's emergency landing and quick response from an ambulance crew on the runway.[263]

In January 2021 Bellingcat, The Insider and Der Spiegel linked the unit that tracked Navalny to other deaths, including activists Timur Kuashev in 2014 and Ruslan Magomedragimov in 2015, and politician Nikita Isayev in 2019.[264] In February, another joint investigation found that Russian opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza was followed by the same unit before his suspected poisonings.[265]

The European Union, United Kingdom and United States responded to the poisoning by imposing sanctions on senior Russian officials.[266][267][268][269]

Return to Russia and imprisonment

Imprisonment related to Yves Rocher case

On 17 January 2021 Navalny returned to Russia by plane from Germany, arriving at Sheremetyevo International Airport in Moscow after the flight was diverted from Vnukovo Airport. At passport control, he was detained. The Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) confirmed his detention and said that he would remain in custody until the court hearing.[270] Prior to his return, the FSIN had said that Navalny might face jail time upon his arrival in Moscow for violating the terms of his probation by leaving Russia, saying it would be "obliged" to detain him once he returned;[30] in 2014, Navalny received a suspended sentence in the Yves Rocher case, which he called politically motivated and in 2017, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Navalny was unfairly convicted.[271][272] Amnesty International declared Navalny to be a prisoner of conscience and called on the Russian authorities to release him.[273] A court decision on 18 January ordered the detention of Navalny until 15 February for violating his parole. A makeshift court was set up in the police station where Navalny was being held. Another hearing would later be held to determine whether his suspended sentence should be replaced with a jail term.[274] Navalny described the procedure as "ultimate lawlessness" and called on his supporters to take to the streets.[275] Human Rights Centre Memorial recognised Navalny as a political prisoner.[276][277] The next day, while in jail, an investigation by Navalny and the FBK was published accusing President Vladimir Putin of corruption.[278] The investigation and his arrest led to mass protests across Russia beginning on 23 January 2021.[279][280]

A Moscow court on 2 February replaced Navalny's three and a half-year suspended sentence with a prison sentence, minus the amount of time he spent under house arrest, meaning he would spend over two and half years in a corrective labour colony.[281][282] The verdict was condemned by the governments of the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France and others as well as the EU.[283][284][285][286][287][288] Immediately after the verdict was announced, protests in a number of Russian cities were held and met with a harsh police crackdown.[289] Navalny later returned to court for a trial on slander charges, where he was accused of defaming a World War II veteran who took part in a promotional video backing the constitutional amendments last year. The case was launched in June 2020 after Navalny called those who took part in the video "corrupt lackeys" and "traitors". Navalny called the case politically motivated and accused authorities of using the case to smear his reputation. Although the charge is punishable by up to two years in prison if proven, his lawyer said that Navalny cannot face a custodial sentence because the law was changed to make it a jailable offence after the alleged crime had taken place.[290][291]

The European Court of Human Rights ruled on 16 February that the Russian government should release Navalny immediately, with the court saying that the resolution was made in "regard to the nature and extent of risk to the applicant's life". Navalny's lawyers applied to the court for an "interim measure" for his release on 20 January after his detention. However Russian officials indicated that they would not comply with the decision. Justice Minister Konstantin Chuychenko called the measure a "flagrant intervention in the operation of a judicial system of a sovereign state" as well as "unreasonable and unlawful", claiming that it did not "contain any reference to any fact or any norm of the law, which would have allowed the court to take this decision". In December 2020, a series of laws were also passed and signed that gave the constitution precedence over rulings made by international bodies as well international treaties.[292][293][294][295] A few days later, a Moscow court rejected Navalny's appeal and upheld his prison sentence, however it reduced his sentence by six weeks after deciding to count his time under house arrest as part of his time served. Another court convicted Navalny on slander charges against the World War II veteran, fining him 850,000 rubles ($11,500).[296]

In February 2021 Amnesty International stripped Navalny of "prisoner of conscience" status, due to lobbying about videos and pro-nationalist statements he made in the past that allegedly constitute hate speech.[297][298][299][300] This designation was then reinstated in May 2021: the international organisation stated that the withdrawal of the "prisoner of conscience" designation had been used as a pretext by the Government of the Russian Federation to further violate Navalny's human rights.[8]

A resolution by the ECHR called for his release.[301]

Navalny was reported on 28 February to have recently arrived at the Pokrov correctional colony in Vladimir Oblast, a prison where Dmitry Demushkin and Konstantin Kotov were also jailed.[302][303][304] In early March, the European Union and United States imposed sanctions on senior Russian officials in response to Navalny's poisoning and imprisonment.[269]

In March, while in prison, Navalny in a formal complaint accused authorities of torture by depriving him of sleep, where he is considered a flight risk by authorities. Navalny told lawyers that he is woken up eight times a night by guards announcing to a camera that he is in his prison cell. A lawyer of Navalny said that he is suffering from health problems, including a loss of sensation in his spine and legs, and that prison authorities denied Navalny's requests for a civilian physician, claiming his health was "satisfactory".[305][306] On 31 March, Navalny announced a hunger strike to demand proper medical treatment.[307] On 6 April, six doctors, including Navalny's personal physician, Anastasia Vasilyeva, and two CNN correspondents, were arrested outside the prison when they attempted to visit Navalny whose health significantly deteriorated.[308][309] On 7 April 2021, Navalny's attorneys claimed he had suffered two spinal disc herniations and had lost feeling in his hands, prompting criticism from the U.S. government.[310][311] Agnès Callamard, Secretary General of Amnesty International accused Vladimir Putin of slowly killing Alexei Navalny through torture and inhumane treatment in prison.[312][313] He also complained that he was not allowed to read newspapers or have any books including a copy of the Quran that he planned to study.[314]

On 17 April, it was reported that Navalny was in immediate need of medical attention. Navalny's personal doctor Anastasia Vasilyeva and three other doctors, including cardiologist Yaroslav Ashikhmin, asked prison officials to grant them immediate access, stating on social media that "our patient can die any minute", due to an increased risk of a fatal cardiac arrest or kidney failure "at any moment".[315][316] Test results obtained by Navalny's lawyers showed heightened levels of potassium in the blood, which can bring on cardiac arrest, and sharply elevated creatinine levels, indicating impaired kidneys. Navalny's results showed blood potassium levels of 7.1 mmol; blood potassium levels higher than 6.0 mmol (millimoles) per liter usually require immediate treatment.[317][318]

Later that night, an open letter, addressed to Putin and open for Russian citizens to sign, was signed and published by 11 politicians representing several regional parliaments, demanding an independent doctor be allowed to visit Navalny, and for a review and cancellation of all of his criminal cases. "We regard what is happening in relation to Navalny as an attempt on the life of a politician, committed out of personal and political hatred," says the letter, "You, the President of the Russian Federation, personally bear responsibility for the life of Alexey Navalny on the territory of the Russian Federation, including in prison facilities – [you bear this responsibility] to Navalny himself, to his relatives, and to the whole world."[319] Among the signatories are chairman of the Pskov regional branch of the Yabloko party, the deputy of the regional assembly Lev Schlosberg, the deputy from Karelia, the ex-chairman of Yabloko Emilia Slabunova, and the deputy of the Moscow City Duma Yevgeny Stupin.[320]

The following day, his daughter called on Russian prison authorities to let her father be checked by doctors in a tweet[321] written from Stanford University, where she is a student. Prominent celebrities such as J.K. Rowling and Jude Law also addressed a letter[322] to Russian authorities asking to provide Navalny with proper medical treatment.[323][324] U.S. president Joe Biden called his treatment "totally unfair" and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said that the Kremlin had been warned "that there will be consequences if Mr. Navalny dies."[325] The European Union's head diplomat Josep Borrell stated that the organisation held the Russian government accountable for Navalny's health conditions. The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, also expressed her concern for his health.[326] However, Russian authorities rebuked such concerns by foreign countries. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that Russian prison officials are monitoring Navalny's health, not the president.[327]

On 19 April Navalny was moved from prison to a hospital for convicts, according to the Russian prison service,[328][326] for "vitamin therapy".[327] On 23 April, Navalny announced that he was ending his hunger strike on advice of his doctors and as he felt his demands had been partially met.[329][330] His newspapers are still being censored as articles are cut out before the newspaper is given to him.[331]

Designation as extremist

On 16 April the Moscow prosecutor office requested the Moscow City Court to designate organisations linked to Navalny including the FBK and his headquarters as extremist organisations, claiming: "Under the disguise of liberal slogans, these organisations are engaged in creating conditions for the destabilisation of the social and socio-political situation."[332] In response, Navalny aide Leonid Volkov stated: "Putin has just announced full-scale mass political repression in Russia."[333]

On 26 April Moscow's prosecutor office ordered Navalny's network of regional offices, including those of the FBK, to cease its activities, pending a court ruling on whether to designate them as extremist organisations. His ally Leonid Volkov explained that it will limit many of the group's activities as prosecutors seek to label the Foundation as "extremists".[334][335] The move was condemned by Germany as well as Amnesty International, which, in a statement, said: "The objective is clear: to raze Alexei Navalny's movement to the ground while he languishes in prison."[336] On 29 April, Navalny's team announced that the political network would be dissolved, in advance of a court ruling in May expected to designate it as extremist.[337] According to Volkov, the headquarters would be transformed into independent political organisations "which will deal with investigations and elections, public campaigns and rallies".[338] On the same day, his allies said that a new criminal case had been opened against Navalny, for allegedly setting up a non-profit organisation that infringed on the rights of citizens.[339] The next day, the leader of Team 29, Ivan Pavlov, who also represents Navalny's team in the extremism case, was detained in Moscow.[340] On 30 April, the financial monitoring agency added Navalny's regional campaign offices to a list of "terrorists and extremists."[341] On 20 May, the head of the Russian prison system and Navalny's ally Ivan Zhdanov reported that Navalny had "more or less" recovered and that his health was generally satisfactory.[342] On 7 June, Navalny was returned to prison after fully recovering from the effects of the hunger strike.[343]

On 9 June Navalny's political network, including his headquarters and the FBK, were designated as extremist organisations and liquidated by the Moscow City Court.[344][345] Vyacheslav Polyga, judge of Moscow City Court, upheld the administrative claim of the prosecutor of Moscow city Denis Popov and, rejecting all the petitions of the defense, decided[346] to recognise Anti-Corruption Foundation as extremist organisation, to liquidate it and to confiscate its assets; similar decision had been taken against Citizens' Rights Protection Foundation; the activity of the Alexei Navalny staff was prohibited (case No.3а-1573/2021).[347] Case hearing was held in camera because, as indicated by advocate Ilia Novikov, the case file including the text of the administrative claim was classified as state secret.[348] According to advocate Ivan Pavlov, Navalny was not the party to the proceedings and the judge refused to give him such status; at the hearing, the prosecutor stated that defendants are extremist organisations because they want the change of power in Russia and they promised to help participants of the protest with payment of administrative and criminal fines and with making a complaints to the European Court of Human Rights.[349] On 4 August 2021, First Appellate Ordinary Court located in Moscow upheld the decision of the court of first instance (case No.66а-3553/2021) and this decision entered into force that day.[350] On 28 December 2021, it was reported that Anti-Corruption Foundation, Citizens' Rights Protection Foundation and 18 natural persons including Alexei Navalny filed a cassation appeals to the Second Cassation Ordinary Court.[351] On 25 March 2022, the Second Cassation Ordinary Court rejected all cassation appeals and upheld the judgements of lower courts (case No.8а-5101/2022).[352]

In October 2021 the Russian prison commission designated Navalny as a "terrorist."[353] In January 2022, Russia added him and his aides to the “terrorists and extremists” list.[354][355] On 28 June 2022, Navalny lost his appeal on his designations as "extremist" and "terrorist".[356]

New charges

In February 2022 Alexei Navalny faced an additional 10 to 15 years in prison in a new trial on fraud and contempt of court charges.[357][358] The charges alleged that he stole $4.7m (£3.5m) of donations given to his political organisations. He was also accused of insulting a judge.[359][358] He was tried in a makeshift courtroom in the corrective colony at which he was imprisoned.[360] Amnesty International independently analysed the trial materials calling the charges "arbitrary" and "politically motivated".[361]

On 21 February, prosecution witness Fyodor Gorozhanko refused to testify against Navalny in the trial, stating that investigators had "pressured" him to testify to the information they wanted and that he did not believe Navalny had committed any crimes.[362] On 24 February, during his trial, Navalny condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine that began that day and asked the court to include his statement to the trial's protocol. He said that it would "lead to a huge number of victims, destroyed futures, and the continuation of this line of impoverishment of the citizens of Russia." He called the war a distraction to the population to "divert their attention from problems that exist inside the country".[363]

On 22 March, Navalny was found guilty of contempt of court and embezzlement and given a 9-year sentence in a maximum-security prison; he was also ordered to pay a fine of 1.2 million rubles.[364] Amnesty International described the trial as a "sham".[35]

On 17 May, Navalny opened an appeal process against the sentence; the court said the process would resume on 24 May after Navalny requested to postpone the hearing to have a family meeting before being transferred.[365] On 24 May, the Moscow City Court upheld the judgement of the court of first instance.[366]

On 31 May, Navalny said that he was officially notified about new charges of extremism brought against him, in which he was facing up to an additional 15 years in prison.[367]

In mid-June, Navalny was transferred to the maximum security prison IK-6 in Melekhovo, Vladimir Oblast.[368][369]

On 11 July, Navalny announced the relaunch of his Anti-Corruption Foundation as an international organization with an advisory board including his wife Yulia Navalnaya, Guy Verhofstadt, Anne Applebaum, and Francis Fukuyama; Navalny also stated that the first contribution to Anti-Corruption Foundation International would be the Sakharov Prize ($50,000) that was awarded to him.[370]

On 7 September, Navalny said that he had been placed in solitary confinement for the fourth time in just over a month, after just being released. He linked his recent treatment to his attempts to establish a labour union in his penal colony and his "6000" list of individuals he has called to be sanctioned.[371] The next day, he said that his attorney-client privilege was revoked with prison authorities accusing him of continuing to commit crimes from prison.[372]

Reception

Political activities

In October 2010 Navalny was the winner of an online poll for the mayor of Moscow, held by Kommersant and Gazeta.Ru.[373][374] He received about 30,000 votes, or 45%, with the closest rival being "Against all candidates" with some 9,000 votes (14%), followed by former First Deputy Prime Minister of Russia Boris Nemtsov with 8,000 votes (12%) out of a total of about 67,000 votes.[375]

The reaction to Navalny's actual mayoral election result in 2013, where he came second, was mixed: Nezavisimaya Gazeta declared, "The voting campaign turned a blogger into a politician",[115] and following an October 2013 Levada Center poll that showed Navalny made it to the list of potential presidential candidates among Russians, receiving a rating of 5%, Konstantin Kalachev, the leader of the Political Expert Group, declared 5% was not the limit for Navalny, and unless something extraordinary happened, he could become "a pretender for a second place in the presidential race".[376] On the other hand, The Washington Post published a column by Milan Svolik that stated the election was fair so the Sobyanin could show a clean victory, demoralising the opposition, which could otherwise run for street protests.[377] Putin's press secretary Dmitry Peskov stated on 12 September, "His momentary result cannot testify his political equipment and does not speak of him as of a serious politician".[378]

When referring to Navalny, Putin never actually pronounced his name in public, referring to him as a "mister" or the like;[379][378] Julia Ioffe took it for a sign of weakness before the opposition politician,[380] and Peskov later stated Putin never pronounced his name in order not to "give [Navalny] a part of his popularity".[381] In July 2015, Bloomberg's sources "familiar with the matter" declared there was an informal prohibition from the Kremlin for senior Russian officials from mentioning Navalny's name.[382] Peskov rejected the assumption there is such a ban; however, in doing so, he did not mention Navalny's name either.[383]

Ratings

In a 2013 Levada Center poll, Navalny's recognition among the Russian population stood at 37%.[384] Out of those who were able to recognise Navalny, 14% would either "definitely" or "probably" support his presidential run.[385]

The Levada Center also conducted another survey, which was released on 6 April 2017, showing Navalny's recognition among the Russian population at 55%.[386] Out of those who recognised Navalny, 4% would "definitely" vote for him and 14% would "probably" vote for him in the presidential election.[386] In another poll carried out by the same pollster in August 2020, 4% of respondents said that they trusted Navalny the most (out of a list of politicians), an increase from 2% in the previous month.[387]

According to polls conducted by the Levada Center in September 2020, 20% of Russians approve Navalny's activities, 50% disapprove, and 18% had never heard of him.[388] Out of those who were able to recognise Navalny, 10% said that they have "respect" for him, 8% have sympathy and 15% "could not say anything bad" about him. 31% are "neutral" towards him, 14% "could not say anything good" about him and 10% dislike him.[389][388]

Criminal cases

During and after the Kirovles trial, a number of prominent people expressed support to Navalny and/or condemned the trial. The last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev called it "proof that we do not have independent courts".[390] Former Minister of Finance Alexei Kudrin stated that it was "looking less like a punishment than an attempt to isolate him from social life and the electoral process".[391] It was also criticised by novelist Boris Akunin,[392] and jailed Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who called it similar to the treatment of political opponents during the Soviet era.[391]

Vladimir Zhirinovsky, leader of the nationalist LDPR, called the verdict "a direct warning to our 'fifth column'", and added, "This will be the fate of everyone who is connected with the West and works against Russia".[391] A variety of state officials condemned the verdict. United States Department of State Deputy Spokesperson Marie Harf stated that the United States was "very disappointed by the conviction and sentencing of opposition leader Aleksey Navalniy".[393] The spokesperson for European Union High Representative Catherine Ashton said that the outcome of the trial "raises serious questions as to the state of the rule of law in Russia".[391][394] Andreas Schockenhoff, Germany's Commissioner for German-Russian Coordination, stated, "For us, it's further proof of authoritarian policy in Russia, which doesn't allow diversity and pluralism".[395] The New York Times commented in response to the verdict that "President Vladimir Putin of Russia actually seems weak and insecure".[390]

The verdict in the case of Yves Rocher caused similar reactions. According to Alexei Venediktov, the verdict was "unfair", Oleg Navalny was taken "hostage", while Alexei was not jailed to avoid "furious reaction" from Putin, which was caused by the change of measure of restraint after the Kirovles trial.[396] A number of deputies appointed by United Russia and LDPR found the verdict too mild.[397] Experts interviewed by the BBC Russian Service expressed reactions close to the political positions their organisations generally stand on.[398] The spokesperson for EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini stated the same day that the sentence was likely to be politically motivated.[221]