Haile Selassie: Difference between revisions

→Early life: Some interesting infos Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Reverted references removed Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

===Early life=== |

===Early life=== |

||

[[File:Lij Teferi and his father, Ras Makonnen.jpg|thumb|upright|''Ras'' Makonnen Woldemikael and his son ''Lij'' Tafari Makonnen|alt=|left]] |

[[File:Lij Teferi and his father, Ras Makonnen.jpg|thumb|upright|''Ras'' Makonnen Woldemikael and his son ''Lij'' Tafari Makonnen|alt=|left]] |

||

Haile Selassie's royal line (through his father's mother) descended from the Shewan [[Amhara people|Amhara]] Solomonic King, [[Sahle Selassie]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pétridès |first1=S. Pierre |title=Le Héros d'Adoua: Ras Makonnen, Prince d'Éthiopie |date=1963 |publisher=Librairie Plon |location=8, rue Garancière, Paris |page=299}}</ref> He was born on 23 July 1892, in the village of [[Ejersa Goro]], in the [[Harar]] province of Ethiopia. Haile Selassie's mother was paternally of [[Oromo people|Oromo]] descent and maternally of [[Gurage people|Gurage]] heritage, while his father was maternally of [[Amhara people|Amhara]] descent but his paternal lineage remains disputed.<ref>{{cite book |last=Bridgette |first=Kasuka |date=2012 |title= Prominent African Leaders Since Independence |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k2nxqV2R7_8C&dq=kasuka+prominent+african+leaders&pg=PA19 |location=Tanzania |publisher=New Africa Press |page=19 |isbn=9781470043582}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Henze |first=Paul B |author-link= |date=2001 |title=Layers of time a history of Ethiopia |location=New York |publisher=Palgrave |page=189 |isbn=}}</ref><ref name="Woodward">Woodward, Peter (1994), ''Conflict and Peace in the Horn of Africa: federalism and its alternatives''. Dartmouth Pub. Co. {{ISBN|1-85521486-5}}, p. 29.</ref><ref name="John Ryle">{{cite web |last1=Ryle |first1=John |title=Burying the Emperor |url=https://johnryle.com/?article=burying-the-emperor |website=johnryle.com |publisher=Granta Magazine |access-date=8 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Bailey |first=Wade |author-link= |date=2007 |title=Rastafari and It's Shamanist Origin's |url= |location= |publisher=Lulu.com |page=10 |isbn=9781847993250}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Greenfield |first1=Richard |title=Ethiopia: A New Political History |date=1965 |publisher=Frederick A. Praeger Inc. Publishers |location=United States of America |pages=147–148}}</ref>. |

Haile Selassie's royal line (through his father's mother) descended from the Shewan [[Amhara people|Amhara]] Solomonic King, [[Sahle Selassie]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pétridès |first1=S. Pierre |title=Le Héros d'Adoua: Ras Makonnen, Prince d'Éthiopie |date=1963 |publisher=Librairie Plon |location=8, rue Garancière, Paris |page=299}}</ref> He was born on 23 July 1892, in the village of [[Ejersa Goro]], in the [[Harar]] province of Ethiopia. Haile Selassie's mother was paternally of [[Oromo people|Oromo]] descent and maternally of [[Gurage people|Gurage]] heritage, while his father was maternally of [[Amhara people|Amhara]] descent but his paternal lineage remains disputed.<ref>{{cite book |last=Bridgette |first=Kasuka |date=2012 |title= Prominent African Leaders Since Independence |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k2nxqV2R7_8C&dq=kasuka+prominent+african+leaders&pg=PA19 |location=Tanzania |publisher=New Africa Press |page=19 |isbn=9781470043582}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Henze |first=Paul B |author-link= |date=2001 |title=Layers of time a history of Ethiopia |location=New York |publisher=Palgrave |page=189 |isbn=}}</ref><ref name="Woodward">Woodward, Peter (1994), ''Conflict and Peace in the Horn of Africa: federalism and its alternatives''. Dartmouth Pub. Co. {{ISBN|1-85521486-5}}, p. 29.</ref><ref name="John Ryle">{{cite web |last1=Ryle |first1=John |title=Burying the Emperor |url=https://johnryle.com/?article=burying-the-emperor |website=johnryle.com |publisher=Granta Magazine |access-date=8 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Bailey |first=Wade |author-link= |date=2007 |title=Rastafari and It's Shamanist Origin's |url= |location= |publisher=Lulu.com |page=10 |isbn=9781847993250}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Greenfield |first1=Richard |title=Ethiopia: A New Political History |date=1965 |publisher=Frederick A. Praeger Inc. Publishers |location=United States of America |pages=147–148}}</ref>. Haile Selassie paternal grandfather belonged to a noble family from [[Shewa]] and was the governor of the districts of [[Menz]] and [[Doba Ethiopia|Doba]] which are located in [[North Shewa Zone (Amhara)|Semien Shewa]].<ref name="Pétridès-28">S. Pierre Pétridès, ''Le Héros d'Adoua. Ras Makonnen, Prince d'Éthiopie'', {{p.|28}}</ref> His mother was [[Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles#Woyzero|Woizero]] ("Lady") [[Yeshimebet Ali]] Abba Jifar, daughter of a ruling chief from [[Were Ilu (woreda)|Were Ilu]] in [[Wollo]] province, [[Dejazmach]] Ali Abba Jifar.<ref name="Moor">de Moor, Jaap, and Wesseling, H. L. (1989), ''Imperialism and War: Essays on Colonial Wars in Asia and Africa''. Brill. {{ISBN|9004088342}}, p. 189.</ref> His maternal grandmother was of [[Gurage people|Gurage]] heritage.<ref name="Woodward" /> Haile Selassie's father was [[Ras (title)|Ras]] [[Makonnen Wolde Mikael]], the grandson of King [[Sahle Selassie]] who was once the ruler of [[Shewa]]. He served as a general in the [[First Italo–Ethiopian War]], playing a key role at the [[Battle of Adwa]];<ref name="Moor" /> Haile Selassie was thus able to ascend to the imperial throne through his paternal grandmother, Woizero Tenagnework Sahle Selassie, who was an aunt of Emperor [[Menelik II]] and daughter of the Solomonic Amhara King of Shewa, [[Negus]] Sahle Selassie. As such, Haile Selassie claimed direct descent from [[Makeda]], the Queen of Sheba, and King Solomon of ancient Israel.{{Sfn |Shinn | p = 265}} |

||

Ras Makonnen arranged for Tafari as well as his first cousin, [[Imru Haile Selassie]], to receive instruction in Harar from [[Abba Samuel Wolde Kahin]], an Ethiopian [[Order of Friars Minor Capuchin|Capuchin monk]], and from Dr. Vitalien, a surgeon from [[Guadeloupe]]. Tafari was named [[Dejazmach]] (literally "commander of the gate", roughly equivalent to "[[count]]"){{Sfn | Selassie | 1999 | loc = vol. 2, p. xii}} at the age of 13, on 1 November 1905.<ref name="so193">{{Harvnb |Shinn | pp = 193–4}}.</ref><ref name="Autobiography Vol. I (Hardcover) p.20"/> Shortly thereafter, his father Ras Makonnen died at [[Kulibi]], in 1906.<ref name=rad712>{{Harvnb |Roberts | p = 712}}.</ref> |

Ras Makonnen arranged for Tafari as well as his first cousin, [[Imru Haile Selassie]], to receive instruction in Harar from [[Abba Samuel Wolde Kahin]], an Ethiopian [[Order of Friars Minor Capuchin|Capuchin monk]], and from Dr. Vitalien, a surgeon from [[Guadeloupe]]. Tafari was named [[Dejazmach]] (literally "commander of the gate", roughly equivalent to "[[count]]"){{Sfn | Selassie | 1999 | loc = vol. 2, p. xii}} at the age of 13, on 1 November 1905.<ref name="so193">{{Harvnb |Shinn | pp = 193–4}}.</ref><ref name="Autobiography Vol. I (Hardcover) p.20"/> Shortly thereafter, his father Ras Makonnen died at [[Kulibi]], in 1906.<ref name=rad712>{{Harvnb |Roberts | p = 712}}.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:26, 3 October 2022

| Haile Selassie I ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negusa Nagast Defender of the Faith | |||||

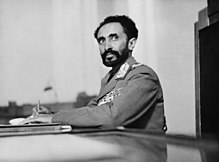

Haile Selassie in dress uniform, 1970 | |||||

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |||||

| Reign | 2 April 1930 – 2 May 1936[nb 1] 20 January 1941 – 12 September 1974 | ||||

| Coronation | 2 November 1930 | ||||

| Predecessor | Zewditu | ||||

| Successor | Amha Selassie | ||||

| Prime Minister | |||||

| Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia | |||||

| Reign | 27 September 1916 – 2 April 1930 | ||||

| Predecessor | Tessema Nadew | ||||

| Successor | Ijigayehu Amha Selassie | ||||

| Monarch | Zewditu | ||||

| Born | Tafari Makonnen 23 July 1892 Ejersa Goro, Harar, Ethiopian Empire | ||||

| Died | 27 August 1975 (aged 83) National Palace, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | ||||

| Burial | 5 November 2000 | ||||

| Spouse | Menen Asfaw | ||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | House of Solomon (Shewan branch) | ||||

| Father | Makonnen Wolde Mikael | ||||

| Mother | Yeshimebet Ali | ||||

| Religion | Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo | ||||

| Signature | |||||

| 1st and 5th Chairperson of the Organisation of African Unity | |||||

| In office 25 May 1963 – 17 July 1964 | |||||

| Succeeded by | Gamal Abdel Nasser | ||||

| In office 5 November 1966 – 11 September 1967 | |||||

| Preceded by | Joseph Arthur Ankrah | ||||

| Succeeded by | Joseph-Désiré Mobutu | ||||

Haile Selassie I (Template:Lang-gez,[nb 2] Template:IPA-am;[nb 3] born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 1892 – 27 August 1975)[4] was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (Enderase) for Empress Zewditu from 1916. Haile Selassie is widely considered a defining figure in modern Ethiopian history, and the key figure of Rastafari, a religious movement in Jamaica which emerged shortly after he became emperor in the 1930s.[5][6] He was a member of the Solomonic dynasty which claims to trace lineage to Emperor Menelik I, believed to be the son of King Solomon and Makeda the Queen of Sheba.

Haile Selassie attempted to modernize the country through a series of political and social reforms, including the introduction of the 1931 constitution, its first written constitution, and the abolition of slavery. He led the failed efforts to defend Ethiopia during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and spent most of the period of Italian occupation exiled in England. In 1940, he traveled to Sudan in order to assist in coordinating the anti-fascist struggle in Ethiopia, and returned to his home country in 1941 after the East African campaign. He dissolved the Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea, which was established by the UN General Assembly in 1950, and annexed Eritrea into Ethiopia as one of its provinces, while fighting to prevent secession.[7]

Haile Selassie's internationalist views led to Ethiopia becoming a charter member of the United Nations.[8] In 1963, he presided over the formation of the Organisation of African Unity, the precursor of the African Union, and served as its first chairman. In 1974, he was overthrown in a military coup by a Marxist–Leninist junta, the Derg. Haile Selassie was assassinated on 27 August 1975.[9][10]

Among some members of the Rastafari movement, Haile Selassie is referred to as the returned messiah of the Bible, God incarnate. This distinction notwithstanding, he was a Christian and adhered to the tenets and liturgy of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[11][12] The Rastafari movement was founded in Jamaica sometime around 1930 and its followers are estimated at between 700,000 and one million as of 2012.[13]

He has been criticized by some historians for his suppression of rebellions among the landed aristocracy (the mesafint), which consistently opposed his reforms; some critics have also criticized Ethiopia's failure to modernize rapidly enough.[14][15] During his rule the Harari people were persecuted and many left the Harari Region.[16] His regime was also criticized by human rights groups, such as Human Rights Watch, as autocratic and illiberal.[15][17] Although some sources state that late during his regime the Oromo language was banned from education, public speaking and use in administration[18][19][20] there was never an official law or government policy that criminalized any language.[21][22][23] The Haile Selassie government relocated numerous Amharas into southern Ethiopia where they served in government administration, courts, and church.[24][25][26] Following the death of Hachalu Hundessa in June 2020, the Statue of Haile Selassie in Cannizaro Park, London was destroyed by Oromo protesters, and his father's equestrian monument in Harar was removed.[27][28][29]

Name

| Styles of Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style |

|

| Spoken style |

|

| Alternative style |

|

Haile Selassie was known as a child as Lij Tafari Makonnen (Amharic: ልጅ ተፈሪ መኮንን; Lij Teferī Mekōnnin). Lij is translated as "child" and serves to indicate that a youth is of noble blood. His given name, Tafari, means "one who is respected or feared." Like most Ethiopians, his personal name "Tafari" is followed by that of his father Makonnen and that of his grandfather Woldemikael. His name, Haile Selassie, was given to him at his infant baptism and adopted again as part of his regnal name in 1930.

On 1 November 1905, at the age of thirteen years and three months old, his father appointed him Dejazmatch of Gara Mulatta (a region some twenty miles southwest of Harar).[30] The literal translation of Dejazmatch is "keeper of the door" and it's a title of nobility equivalent to a Count.[31] On 27 September 1916, he was pronounced Crown Prince, Heir Apparent to the Throne (Alga Worrach)[32][33] and appointed to the position of Regent Plenipotentiary (Balemulu Silt'an Enderase).[32][34] On 11 February 1917 he was crowned Le'ul-Ras[35] and became known as Ras Tafari Makonnen ⓘ. Ras is translated as "head"[36][33] and is a rank of nobility equivalent to Duke;[33][37] though it is often rendered in translation as "prince." Originally the title Le'ul, which means "Your Highness," was only ever used as a form of address[38] however in 1917 the title Le'ul-Ras replaced the senior office of Ras Bitwoded and is the equivalent of a Royal Duke.[39][40] In 1928, Empress Zewditu planned on granting him the throne of Shewa, however at the last moment opposition from certain provincial rulers caused a change and his title Negus or "King" was conferred without geographical qualification or definition.[41][42]

On 2 November 1930, after the death of Empress Zewditu, Tafari was crowned Negusa Nagast, literally King of Kings, rendered in English as "Emperor".[43] Upon his ascension, he took as his regnal name Haile Selassie I. Haile means in Ge'ez "Power of" and Selassie means trinity—therefore Haile Selassie roughly translates to "Power of the Trinity".[44] Haile Selassie's full title in office was "By the Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Elect of God".[45][35][38][40][46][47][48][nb 4] This title reflects Ethiopian dynastic traditions, which hold that all monarchs must trace their lineage to Menelik I, who is described by the Kebra Nagast (a 14th-century CE national epic) as the son of the tenth-century BCE King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.[50]

To Ethiopians, Haile Selassie has been known by many names, including Janhoy, Talaqu Meri, and Abba Tekel.[49] The Rastafari movement employs many of these appellations, also referring to him as Jah, Jah Jah, Jah Rastafari, and HIM (the abbreviation of "His Imperial Majesty").[49]

Biography

Early life

Haile Selassie's royal line (through his father's mother) descended from the Shewan Amhara Solomonic King, Sahle Selassie.[51] He was born on 23 July 1892, in the village of Ejersa Goro, in the Harar province of Ethiopia. Haile Selassie's mother was paternally of Oromo descent and maternally of Gurage heritage, while his father was maternally of Amhara descent but his paternal lineage remains disputed.[52][53][54][55][56][57]. Haile Selassie paternal grandfather belonged to a noble family from Shewa and was the governor of the districts of Menz and Doba which are located in Semien Shewa.[58] His mother was Woizero ("Lady") Yeshimebet Ali Abba Jifar, daughter of a ruling chief from Were Ilu in Wollo province, Dejazmach Ali Abba Jifar.[59] His maternal grandmother was of Gurage heritage.[54] Haile Selassie's father was Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael, the grandson of King Sahle Selassie who was once the ruler of Shewa. He served as a general in the First Italo–Ethiopian War, playing a key role at the Battle of Adwa;[59] Haile Selassie was thus able to ascend to the imperial throne through his paternal grandmother, Woizero Tenagnework Sahle Selassie, who was an aunt of Emperor Menelik II and daughter of the Solomonic Amhara King of Shewa, Negus Sahle Selassie. As such, Haile Selassie claimed direct descent from Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, and King Solomon of ancient Israel.[60]

Ras Makonnen arranged for Tafari as well as his first cousin, Imru Haile Selassie, to receive instruction in Harar from Abba Samuel Wolde Kahin, an Ethiopian Capuchin monk, and from Dr. Vitalien, a surgeon from Guadeloupe. Tafari was named Dejazmach (literally "commander of the gate", roughly equivalent to "count")[61] at the age of 13, on 1 November 1905.[62][30] Shortly thereafter, his father Ras Makonnen died at Kulibi, in 1906.[63]

Governorship

Tafari assumed the titular governorship of Selale in 1906, a realm of marginal importance,[64] but one that enabled him to continue his studies.[62] In 1907, he was appointed governor over part of the province of Sidamo. It is alleged that during his late teens, Haile Selassie was married to Woizero Altayech, and that from this union, his daughter Princess Romanework was born.[65]

Following the death of his brother Yelma in 1907, the governorate of Harar was left vacant,[64] and its administration was left to Menelik's loyal general, Dejazmach Balcha Safo. Balcha Safo's administration of Harar was ineffective, and so during the last illness of Menelik II, and the brief reign of Empress Taitu Bitul, Tafari was made governor of Harar in 1910[63] or 1911.[66]

On 3 August 1911, he married Menen Asfaw of Ambassel, niece of the heir to the throne Lij Iyasu.

Regency

The extent to which Tafari Makonnen contributed to the movement that would come to depose Lij Iyasu has been discussed extensively, particularly in Haile Selassie's own detailed account of the matter. Iyasu was the designated but uncrowned emperor of Ethiopia from 1913 to 1916. Iyasu's reputation for scandalous behavior and a disrespectful attitude towards the nobles at the court of his grandfather, Menelik II,[67] damaged his reputation. Iyasu's flirtation with Islam was considered treasonous among the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian leadership of the empire. On 27 September 1916, Iyasu was deposed.[68]

Contributing to the movement that deposed Iyasu were conservatives such as Fitawrari Habte Giyorgis, Menelik II's longtime Minister of War. The movement to depose Iyasu preferred Tafari, as he attracted support from both progressive and conservative factions. Ultimately, Iyasu was deposed on the grounds of conversion to Islam.[36][68] In his place, the daughter of Menelik II (the aunt of Iyasu) was named Empress Zewditu, while Tafari was elevated to the rank of Ras and was made heir apparent and Crown Prince. In the power arrangement that followed, Tafari accepted the role of Regent Plenipotentiary (Balemulu 'Inderase)[nb 5] and became the de facto ruler of the Ethiopian Empire (Mangista Ityop'p'ya). Zewditu would govern while Tafari would administer.[71] While Iyasu had been deposed on 27 September 1916, on 8 October he managed to escape into the Ogaden Desert and his father, Negus Mikael of Wollo, had time to come to his aid.[72] On 27 October, Negus Mikael and his army met an army under Fitawrari Habte Giyorgis loyal to Zewditu and Tafari. During the Battle of Segale, Negus Mikael was defeated and captured. Any chance that Iyasu would regain the throne was ended, and he went into hiding. On 11 January 1921, after avoiding capture for about five years, Iyasu was taken into custody by Gugsa Araya Selassie.

On 11 February 1917, the coronation for Zewditu took place. She pledged to rule justly through her Regent, Tafari. While Tafari was the more visible of the two, Zewditu was far from an honorary ruler. Her position required that she arbitrate the claims of competing factions. In other words, she had the last word. Tafari carried the burden of daily administration, but, because his position was relatively weak, this was often an exercise in futility. Initially his personal army was poorly equipped, his finances were limited, and he had little leverage to withstand the combined influence of the Empress, the Minister of War, or the provincial governors.[72]

During his Regency, the new Crown Prince developed the policy of cautious modernization initiated by Menelik II. Also, during this time, he survived the 1918 flu pandemic, having come down with the illness.[73] He secured Ethiopia's admission to the League of Nations in 1923 by promising to eradicate slavery; each emperor since Tewodros II had issued proclamations to halt slavery,[74] but without effect: the internationally scorned practice persisted well into Haile Selassie's reign with an estimated 2 million slaves in Ethiopia in the early 1930s.[75][76]

Travel abroad

In 1924, Ras Tafari toured Europe and the Middle East visiting Jerusalem, Alexandria, Paris, Luxembourg, Brussels, Amsterdam, Stockholm, London, Geneva, and Athens. With him on his tour was a group that included Ras Seyum Mangasha of western Tigray Province; Ras Hailu Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam province; Ras Mulugeta Yeggazu of Illubabor Province; Ras Makonnen Endelkachew; and Blattengeta Heruy Welde Sellase. The primary goal of the trip to Europe was for Ethiopia to gain access to the sea. In Paris, Tafari was to find out from the French Foreign Ministry (Quai d'Orsay) that this goal would not be realized.[77] However, failing this, he and his retinue inspected schools, hospitals, factories, and churches. Although patterning many reforms after European models, Tafari remained wary of European pressure. To guard against economic imperialism, Tafari required that all enterprises have at least partial local ownership.[78] Of his modernization campaign, he remarked, "We need European progress only because we are surrounded by it. That is at once a benefit and a misfortune."[79]

Throughout Tafari's travels in Europe, the Levant, and Egypt, he and his entourage were greeted with enthusiasm and fascination. Seyum Mangasha accompanied him and Hailu Tekle Haymanot who, like Tafari, were sons of generals who contributed to the victorious war against Italy a quarter-century earlier at the Battle of Adwa.[80] Another member of his entourage, Mulugeta Yeggazu, actually fought at Adwa as a young man. The "Oriental Dignity" of the Ethiopians[81] and their "rich, picturesque court dress"[82] were sensationalized in the media; among his entourage he even included a pride of lions, which he distributed as gifts to President Alexandre Millerand and Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré of France, to King George V of the United Kingdom, and to the Zoological Garden (Jardin Zoologique) of Paris, France.[80] As one historian noted, "Rarely can a tour have inspired so many anecdotes".[80] In return for two lions, the United Kingdom presented Tafari with the imperial crown of Emperor Tewodros II for its safe return to Empress Zewditu. The crown had been taken by General Sir Robert Napier during the 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia.[83]

In this period, the Crown Prince visited the Armenian monastery of Jerusalem. There, he adopted 40 Armenian orphans (አርባ ልጆች Arba Lijoch, "forty children"), who had lost their parents during the Armenian Genocide. Tafari arranged for the musical education of the youths, and they came to form the imperial brass band.[84]

King and Emperor

Tafari's authority was challenged in 1928 when Dejazmach Balcha Safo went to Addis Ababa with a sizeable armed force. When Tafari consolidated his hold over the provinces, many of Menelik's appointees refused to abide by the new regulations. Balcha Safo, the governor (Shum) of coffee-rich Sidamo Province, was particularly troublesome. The revenues he remitted to the central government did not reflect the accrued profits and Tafari recalled him to Addis Ababa. The old man came in high dudgeon and, insultingly, with a large army.[nb 6] The Dejazmatch paid homage to Empress Zewditu, but snubbed Tafari.[85][86] On 18 February, while Balcha Safo and his personal bodyguard[nb 7] were in Addis Ababa, Tafari had Ras Kassa Haile Darge buy off his army and arranged to have him displaced as the Shum of Sidamo Province[87] by Birru Wolde Gabriel who himself was replaced by Desta Damtew.[72]

Even so, the gesture of Balcha Safo empowered Empress Zewditu politically and she attempted to have Tafari tried for treason. He was tried for his benevolent dealings with Italy including a 20-year peace accord which was signed on 2 August.[62] In September, a group of palace reactionaries including some courtiers of the empress, made a final bid to get rid of Tafari. The attempted coup d'état was tragic in its origins and comic in its end. When confronted by Tafari and a company of his troops, the ringleaders of the coup took refuge on the palace grounds in Menelik's mausoleum. Tafari and his men surrounded them only to be surrounded themselves by the personal guard of Zewditu. More of Tafari's khaki clad soldiers arrived and decided the outcome in his favor with superiority of arms.[88] Popular support, as well as the support of the police,[85] remained with Tafari. Ultimately, the Empress relented and, on 7 October 1928, she crowned Tafari as Negus (Amharic: "King").

The crowning of Tafari as King was controversial. He occupied the same territory as the empress rather than going off to a regional kingdom of the empire. Two monarchs, even with one being the vassal and the other the emperor (in this case empress), had never occupied the same location as their seat in Ethiopian history. Conservatives agitated to redress this perceived insult to the crown's dignity, leading to the rebellion of Ras Gugsa Welle. Gugsa Welle was the husband of the empress and the Shum of Begemder Province. In early 1930, he raised an army and marched it from his governorate at Gondar towards Addis Ababa. On 31 March 1930, Gugsa Welle was met by forces loyal to Negus Tafari and was defeated at the Battle of Anchem. Gugsa Welle was killed in action.[89] News of Gugsa Welle's defeat and death had hardly spread through Addis Ababa when the empress died suddenly on 2 April 1930. Although it was long rumored that the empress was poisoned upon her husband's defeat,[90] or alternately that she died from shock upon hearing of the death of her estranged yet beloved husband,[91] it has since been documented that the Empress succumbed to paratyphoid fever and complications from diabetes after the Orthodox clergy imposed strict rules concerning her diet against her physicians orders with regards to Lent.[92][93]

Upon Zewditu's death, Tafari himself rose to emperor and was proclaimed Neguse Negest ze-'Ityopp'ya, "King of Kings of Ethiopia". He was crowned on 2 November 1930, at Addis Ababa's Cathedral of St. George. The coronation was by all accounts "a most splendid affair",[94] and it was attended by royals and dignitaries from all over the world. Among those in attendance were The Duke of Gloucester (King George V's son), Marshal Louis Franchet d'Espèrey of France, and the Prince of Udine representing King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. Emissaries from the United States,[95] Egypt, Turkey, Sweden, Belgium, and Japan were also present.[94] British author Evelyn Waugh was also present, penning a contemporary report on the event, and American travel lecturer Burton Holmes shot the only known film footage of the event.[96][97] One newspaper report suggested that the celebration had incurred a cost in excess of $3,000,000.[98] Many of those in attendance received lavish gifts;[99] in one instance, the Christian emperor even sent a gold-encased Bible to an American bishop who had not attended the coronation, but who had dedicated a prayer to the emperor on the day of the coronation.[100]

Haile Selassie introduced Ethiopia's first written constitution on 16 July 1931,[101] providing for a bicameral legislature.[102] The constitution kept power in the hands of the nobility, but it did establish democratic standards among the nobility, envisaging a transition to democratic rule: it would prevail "until the people are in a position to elect themselves."[102] The constitution limited the succession to the throne to the descendants of Haile Selassie, a point that met with the disapprobation of other dynastic princes, including the princes of Tigrai and even the emperor's loyal cousin, Ras Kassa Haile Darge.

In 1932, the Sultanate of Jimma was formally absorbed into Ethiopia following the death of Sultan Abba Jifar II of Jimma.

Conflict with Italy

Ethiopia became the target of renewed Italian imperialist designs in the 1930s. Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime was keen to avenge the military defeats Italy had suffered to Ethiopia in the First Italo-Abyssinian War, and to efface the failed attempt by "liberal" Italy to conquer the country, as epitomised by the defeat at Adwa.[103][104][105] A conquest of Ethiopia could also empower the cause of fascism and embolden its empire's rhetoric.[105] Ethiopia would also provide a bridge between Italy's Eritrean and Italian Somaliland possessions. Ethiopia's position in the League of Nations did not dissuade the Italians from invading in 1935; the "collective security" envisaged by the League proved useless, and a scandal erupted when the Hoare-Laval Pact revealed that Ethiopia's League allies were scheming to appease Italy.[106]

Mobilization

Following 5 December 1934 Italian invasion of Ethiopia at Welwel, Ogaden Province, Haile Selassie joined his northern armies and set up headquarters at Desse in Wollo province. He issued his mobilization order on 3 October 1935:

If you withhold from your country Ethiopia the death from cough or head-cold of which you would otherwise die, refusing to resist (in your district, in your patrimony, and in your home) our enemy who is coming from a distant country to attack us, and if you persist in not shedding your blood, you will be rebuked for it by your Creator and will be cursed by your offspring. Hence, without cooling your heart of accustomed valour, there emerges your decision to fight fiercely, mindful of your history that will last far into the future… If on your march you touch any property inside houses or cattle and crops outside, not even grass, straw, and dung excluded, it is like killing your brother who is dying with you… You, countryman, living at the various access routes, set up a market for the army at the places where it is camping and on the day your district-governor will indicate to you, lest the soldiers campaigning for Ethiopia's liberty should experience difficulty. You will not be charged excise duty, until the end of the campaign, for anything you are marketing at the military camps: I have granted you remission… After you have been ordered to go to war, but are then idly missing from the campaign, and when you are seized by the local chief or by an accuser, you will have punishment inflicted upon your inherited land, your property, and your body; to the accuser I shall grant a third of your property…

On 19 October 1935, Haile Selassie gave more precise orders for his army to his Commander-in-Chief, Ras Kassa:

- When you set up tents, it is to be in caves and by trees and in a wood, if the place happens to be adjoining to these―and separated in the various platoons. Tents are to be set up at a distance of 30 cubits from each other.

- When an aeroplane is sighted, one should leave large open roads and wide meadows and march in valleys and trenches and by zigzag routes, along places which have trees and woods.

- When an aeroplane comes to drop bombs, it will not suit it to do so unless it comes down to about 100 metres; hence when it flies low for such action, one should fire a volley with a good and very long gun and then quickly disperse. When three or four bullets have hit it, the aeroplane is bound to fall down. But let only those fire who have been ordered to shoot with a weapon that has been selected for such firing, for if everyone shoots who possesses a gun, there is no advantage in this except to waste bullets and to disclose the men's whereabouts.

- Lest the aeroplane, when rising again, should detect the whereabouts of those who are dispersed, it is well to remain cautiously scattered as long as it is still fairly close. In time of war it suits the enemy to aim his guns at adorned shields, ornaments, silver and gold cloaks, silk shirts, and similar things. Whether one possesses a jacket or not, it is best to wear a narrow-sleeved shirt with faded colours. When we return, with God's help, you can wear your gold and silver decorations then. Now it is time to go and fight. We offer you all these words of advice in the hope that no great harm should befall you through lack of caution. At the same time, We are glad to assure you that in time of war. We are ready to shed Our blood in your midst for the sake of Ethiopia's freedom…"[107]

Compared to the Ethiopians, the Italians had an advanced, modern military which included a large air force. The Italians would also come to employ chemical weapons extensively throughout the conflict, even targeting Red Cross field hospitals in violation of the Geneva Conventions.[108]

Progress of the war

Starting in early October 1935, the Italians invaded Ethiopia. But, by November, the pace of invasion had slowed appreciably and Haile Selassie's northern armies were able to launch what was known as the "Christmas Offensive". During this offensive, the Italians were forced back in places and put on the defensive. In early 1936, the First Battle of Tembien stopped the progress of the Ethiopian offensive and the Italians were ready to continue their offensive. Following the defeat and destruction of the northern Ethiopian armies at the Battle of Amba Aradam, the Second Battle of Tembien, and the Battle of Shire, Haile Selassie took the field with the last Ethiopian army on the northern front. On 31 March 1936, he launched a counterattack against the Italians himself at the Battle of Maychew in southern Tigray. The emperor's army was defeated and retreated in disarray. As Haile Selassie's army withdrew, the Italians attacked from the air along with rebellious Raya and Azebo tribesmen on the ground, who were armed and paid by the Italians.[109]

Haile Selassie made a solitary pilgrimage to the churches at Lalibela, at considerable risk of capture, before returning to his capital.[111] After a stormy session of the council of state, it was agreed that because Addis Ababa could not be defended, the government would relocate to the southern town of Gore, and that in the interest of preserving the Imperial house, the emperor's wife Menen Asfaw and the rest of the imperial family should immediately depart for French Somaliland, and from there continue on to Jerusalem.[citation needed]

Exile debate

After further debate as to whether Haile Selassie should go to Gore or accompany his family into exile, it was agreed that he should leave Ethiopia with his family and present the case of Ethiopia to the League of Nations at Geneva. The decision was not unanimous and several participants, including the nobleman Blatta Tekle Wolde Hawariat, strenuously objected to the idea of an Ethiopian monarch fleeing before an invading force.[112] Haile Selassie appointed his cousin Ras Imru Haile Selassie as Prince Regent in his absence, departing with his family for French Somaliland on 2 May 1936.

On 5 May, Marshal Pietro Badoglio led Italian troops into Addis Ababa, and Mussolini declared Ethiopia an Italian province. Victor Emanuel III was proclaimed as the new Emperor of Ethiopia. On the previous day, the Ethiopian exiles had left French Somaliland aboard the British cruiser HMS Enterprise. They were bound for Jerusalem in the British Mandate of Palestine, where the Ethiopian royal family maintained a residence. The Imperial family disembarked at Haifa and then went on to Jerusalem. Once there, Haile Selassie and his retinue prepared to make their case at Geneva. The choice of Jerusalem was highly symbolic, since the Solomonic Dynasty claimed descent from the House of David. Leaving the Holy Land, Haile Selassie and his entourage sailed aboard the British cruiser HMS Capetown for Gibraltar, where he stayed at the Rock Hotel. From Gibraltar, the exiles were transferred to an ordinary liner. By doing this, the United Kingdom government was spared the expense of a state reception.[113]

Collective security and the League of Nations, 1936

Mussolini invaded Ethiopia and promptly declared his own "Italian Empire". After the League of Nations afforded Haile Selassie the opportunity to address the assembly, Italy withdrew its League delegation, on 12 May 1936.[114] It was in this context that Haile Selassie walked into the hall of the League of Nations, introduced by the President of the Assembly as "His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Ethiopia" (Sa Majesté Imperiale, l'Empereur d'Éthiopie). The introduction caused a great many Italian journalists in the galleries to erupt into jeering, heckling, and whistling. As it turned out, they had earlier been issued whistles by Mussolini's son-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano.[115] The Romanian delegate and former League president, Nicolae Titulescu, famously jumped to his feet in response and cried "To the door with the savages!", and the offending journalists were removed from the hall. Haile Selassie waited calmly for the hall to be cleared, and responded "majestically"[116] with a speech considered by some[by whom?] among the most stirring of the 20th century.[117]

Although fluent in French, the League's working language, Haile Selassie chose to deliver his historic speech in his native Amharic. He asserted that, because his "confidence in the League was absolute", his people were now being slaughtered. He pointed out that the same European states that found in Ethiopia's favor at the League of Nations were refusing Ethiopia credit and matériel while aiding Italy, which was employing chemical weapons on military and civilian targets alike.

It was at the time when the operations for the encircling of Makale were taking place that the Italian command, fearing a rout, followed the procedure which it is now my duty to denounce to the world. Special sprayers were installed on board aircraft so that they could vaporize, over vast areas of territory, a fine, death-dealing rain. Groups of nine, fifteen, eighteen aircraft followed one another so that the fog issuing from them formed a continuous sheet. It was thus that, as from the end of January 1936, soldiers, women, children, cattle, rivers, lakes, and pastures were drenched continually with this deadly rain. In order to kill off systematically all living creatures, in order to more surely poison waters and pastures, the Italian command made its aircraft pass over and over again. That was its chief method of warfare.[118]

Noting that his own "small people of 12 million inhabitants, without arms, without resources" could never withstand an attack by a large power such as Italy, with its 42 million people and "unlimited quantities of the most death-dealing weapons", he contended that the aggression threatened all small states, and that all small states were in effect reduced to vassal states in the absence of collective action. He admonished the League that "God and history will remember your judgment."[119]

It is collective security: it is the very existence of the League of Nations. It is the confidence that each State is to place in international treaties… In a word, it is international morality that is at stake. Have the signatures appended to a Treaty value only in so far as the signatory Powers have a personal, direct and immediate interest involved?

The speech made the emperor an icon for anti-fascists around the world, and Time named him "Man of the Year".[120] He failed, however, to get what he most needed: the League agreed to only partial and ineffective sanctions on Italy. Only six nations in 1937 did not recognize Italy's occupation: China, New Zealand, the Soviet Union, the Republic of Spain, Mexico and the United States.[104] It is often said the League of Nations effectively collapsed due to its failure to condemn Italy's invasion of Abyssinia.

Exile

Haile Selassie spent his exile years (1936–41) in Bath, England, in Fairfield House, which he bought. The emperor and Kassa Haile Darge took morning walks together behind the 14-room Victorian house's high walls. Haile Selassie's favorite reading was "diplomatic history." But most of his serious hours were occupied with the 90,000-word story of his life that he was laboriously writing in Amharic.[121]

Prior to Fairfield House, he briefly stayed at Warne's Hotel in Worthing[122] and in Parkside, Wimbledon.[123] A bust of Haile Selassie by Hilda Seligman stood in nearby Cannizaro Park to commemorate this time, and was a popular place of pilgrimage for London's Rastafari community, until it was destroyed by protestors on 30 June 2020.[124] Haile Selassie stayed at the Abbey Hotel in Malvern in the 1930s, and his granddaughters and daughters of court officials were educated at Clarendon School for Girls in North Malvern. During his time in Malvern, he attended services at Holy Trinity Church, in Link Top. A blue plaque, commemorating his stay in Malvern, was unveiled on Saturday, 25 June 2011. As part of the ceremony, a delegation from the Rastafari movement gave a short address and a drum recital.[125][126][127][128][129]

Haile Selassie's activity in this period was focused on countering Italian propaganda as to the state of Ethiopian resistance and the legality of the occupation.[130] He spoke out against the desecration of houses of worship and historical artifacts (including the theft of a 1,600-year-old imperial obelisk), and condemned the atrocities suffered by the Ethiopian civilian population.[131] He continued to plead for League intervention and to voice his certainty that "God's judgment will eventually visit the weak and the mighty alike",[132] though his attempts to gain support for the struggle against Italy were largely unsuccessful until Italy entered World War II on the German side in June 1940.[133]

The emperor's pleas for international support did take root in the United States, particularly among African-American organizations sympathetic to the Ethiopian cause.[134] In 1937, Haile Selassie was to give a Christmas Day radio address to the American people to thank his supporters when his taxi was involved in a traffic accident, leaving him with a fractured knee.[135] Rather than canceling the radio broadcast, he delivered the address, in which he linked Christianity and goodwill with the Covenant of the League of Nations, and asserted that "War is not the only means to stop war":[135]

With the birth of the Son of God, an unprecedented, an unrepeatable, and a long-anticipated phenomenon occurred. He was born in a stable instead of a palace, in a manger instead of a crib. The hearts of the Wise men were struck by fear and wonder due to His Majestic Humbleness. The kings prostrated themselves before Him and worshipped Him. 'Peace be to those who have good will'. This became the first message.

...Although the toils of wise people may earn them respect, it is a fact of life that the spirit of the wicked continues to cast its shadow on this world. The arrogant are seen visibly leading their people into crime and destruction. The laws of the League of Nations are constantly violated and wars and acts of aggression repeatedly take place… So that the spirit of the cursed will not gain predominance over the human race whom Christ redeemed with his blood, all peace-loving people should cooperate to stand firm in order to preserve and promote lawfulness and peace.[135]

During this period, Haile Selassie suffered several personal tragedies. His two sons-in-law, Ras Desta Damtew and Dejazmach Beyene Merid, were both executed by the Italians.[132] The emperor's daughter, Princess Romanework, wife of Dejazmach Beyene Merid, was herself taken into captivity with her children, and she died in Italy in 1941.[136] His daughter Tsehai died during childbirth shortly after the restoration in 1942.[137]

After his return to Ethiopia, he donated Fairfield House to the city of Bath as a residence for the aged.[138] In September 2019 two blue plaques, commemorating Haile Selassie, were unveiled by his grandson, one at Fairfield House and one in Weston-super-Mare, where he has swum in the Tropicana pool.[139]

1940s and 1950s

British forces, which consisted primarily of Ethiopian-backed African and South African colonial troops under the "Gideon Force" of Colonel Orde Wingate, coordinated the military effort to liberate Ethiopia. The emperor himself issued several imperial proclamations in this period, demonstrating that, while authority was not divided up in any formal way, British military might and the emperor's populist appeal could be joined in the concerted effort to liberate Ethiopia.[133]

On 18 January 1941, during the East African Campaign, Haile Selassie crossed the border between Sudan and Ethiopia near the village of Um Iddla. The standard of the Lion of Judah was raised again. Two days later, he and a force of Ethiopian patriots joined Gideon Force which was already in Ethiopia and preparing the way.[140] Italy was defeated by a force of the United Kingdom, the Commonwealth of Nations, Free France, Free Belgium, and Ethiopian patriots. On 5 May 1941, Haile Selassie entered Addis Ababa and personally addressed the Ethiopian people, exactly five years after the fascist forces entered Addis Ababa:

Today is the day on which we defeated our enemy. Therefore, when we say let us rejoice with our hearts, let not our rejoicing be in any other way but in the spirit of Christ. Do not return evil for evil. Do not indulge in the atrocities which the enemy has been practicing in his usual way, even to the last.

Take care not to spoil the good name of Ethiopia by acts which are worthy of the enemy. We shall see that our enemies are disarmed and sent out the same way they came. As Saint George who killed the dragon is the Patron Saint of our army as well as of our allies, let us unite with our allies in everlasting friendship and amity in order to be able to stand against the godless and cruel dragon which has newly risen and which is oppressing mankind.[141]

On 27 August 1942, Haile Selassie confirmed the legal basis for the abolition of slavery that had been enacted by Italy throughout the empire and imposed severe penalties, including death, for slave trading.[142] After World War II, Ethiopia became a charter member of the United Nations. In 1948, the Ogaden, a region disputed with both Italian Somaliland and British Somaliland, was granted to Ethiopia.[143] On 2 December 1950, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 390 (V), establishing the federation of Eritrea (the former Italian colony) into Ethiopia.[144] Eritrea was to have its own constitution, which would provide for ethnic, linguistic, and cultural balance, while Ethiopia was to manage its finances, defense, and foreign policy.[144]

Despite his centralization policies that had been made before World War II, Haile Selassie still found himself unable to push for all the programmes he wanted. In 1942, he attempted to institute a progressive tax scheme, but this failed due to opposition from the nobility, and only a flat tax was passed; in 1951, he agreed to reduce this as well.[145] Ethiopia was still "semi-feudal",[146] and the emperor's attempts to alter its social and economic form by reforming its modes of taxation met with resistance from the nobility and clergy, which were eager to resume their privileges in the post-war era.[145] Where Haile Selassie actually did succeed in effecting new land taxes, the burdens were often still passed by the landowners to the peasants.[145]

Between 1941 and 1959, Haile Selassie worked to establish the autocephaly of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[147] The Ethiopian Orthodox Church had been headed by the Abuna, a bishop who answered to the Pope of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. In 1942 and 1945, Haile Selassie applied to the Holy Synod of the Coptic Orthodox Church to establish the independence of Ethiopian bishops, and when his appeals were denied he threatened to sever relations with the Coptic Church of Alexandria.[147] Finally, in 1959, Pope Kyrillos VI elevated the Abuna to Patriarch-Catholicos.[147] The Ethiopian Church remained affiliated with the Alexandrian Church.[145] In addition to these efforts, Haile Selassie changed the Ethiopian church-state relationship by introducing taxation of church lands, and by restricting the legal privileges of the clergy, who had formerly been tried in their own courts for civil offenses.[145]

In 1948, the Harari Muslims of Harar with Somali allies staged a significant rebellion against the empire; the state responded violently. Hundreds were arrested and the entire town of Harar was put under house arrest.[148] The government also took control of many assets and estates belonging to the people.[149][150] This led to a massive exodus of Hararis from the Harari Region, which had not occurred in their history prior.[16][151] The dissatisfaction of the Harari stemmed from the fact that they had never received limited autonomy of Harar, which was promised by Menelik II after his conquest of the kingdom. The promise was eroded by successive Amhara governors.[152] According to historians Tim Carmicheal and Roman Loimeier, Haile Selassie was directly involved in the suppression of the Harari movement which formed as a response to the crackdown on Hararis who collaborated with the Italians during their occupation of Ethiopia from 1935 to 1941.[153][154]

In keeping with the principle of collective security, for which he was an outspoken proponent, Haile Selassie sent a contingent, under General Mulugueta Bulli, known as the Kagnew Battalion, to take part in the Korean War by supporting the United Nations Command. It was attached to the American 7th Infantry Division, and fought in a number of engagements including the Battle of Pork Chop Hill.[155] In a 1954 speech, Haile Selassie spoke of Ethiopian participation in the Korean War as a redemption of the principles of collective security:

Nearly two decades ago, I personally assumed before history the responsibility of placing the fate of my beloved people on the issue of collective security, for surely, at that time and for the first time in world history, that issue was posed in all its clarity. My searching of conscience convinced me of the rightness of my course and if, after untold sufferings and, indeed, unaided resistance at the time of aggression, we now see the final vindication of that principle in our joint action in Korea, I can only be thankful that God gave me strength to persist in our faith until the moment of its recent glorious vindication.[156]

During the celebrations of his Silver Jubilee in November 1955, Haile Selassie introduced a revised constitution,[157] whereby he retained effective power, while extending political participation to the people by allowing the lower house of parliament to become an elected body. Party politics were not provided for. Modern educational methods were more widely spread throughout the Empire. The country embarked on a development scheme and plans for modernization, tempered by Ethiopian traditions, and within the framework of the state's ancient monarchical structure.

Haile Selassie compromised, when practical, with the traditionalists in the nobility and church. He also tried to improve relations between the state and ethnic groups, and granted autonomy to Afar lands that were difficult to control. Still, his reforms to end feudalism were slow and weakened by the compromises he made with the entrenched aristocracy. The Revised Constitution of 1955 has been criticized for reasserting "the indisputable power of the monarch" and maintaining the relative powerlessness of the peasants.[158]

Haile Selassie also maintained cordial relations with the government of the United Kingdom through charitable gestures. He sent aid to the British government in 1947 when Britain was affected by heavy flooding. His letter to Lord Meork, National Distress Fund, London said, "even though We are busy of helping our people who didn't recover from the crises of the war, We heard that your fertile and beautiful country is devastated by the unusually heavy rain, and your request for aid. Therefore, We are sending small amount of money, about one thousand pounds through our embassy to show our sympathy and cooperation."[159] He also left his home in exile, Fairfield House, Bath, to the City of Bath for the use of the aged in 1959.

1958 famine of Tigray

In the summer of 1958, a widespread famine in the Tigray province of northern Ethiopia was already two years old yet people in Addis Ababa knew hardly anything about it. When significant reports of death finally reached the Ministry of Interior in September 1959 the central government immediately disclosed the information to the public and began asking for contributions. The Emperor personally donated 2,000 tons of relief grain, the U.S. sent 32,000 tons which was distributed between Eritrea and Tigray and money for aid was raised throughout the country but it's estimated that approximately 100,000 people had died before the crisis ended in August 1961. The causes of the famine were attributed to drought, locusts, hailstone and epidemics of small-pox, typhus, measles and malaria.[160][161][162]

1960s

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Haile Selassie contributed Ethiopian troops to the United Nations Operation in the Congo peacekeeping force during the 1960 Congo Crisis, to preserve Congolese integrity, per United Nations Security Council Resolution 143. On 13 December 1960, while Haile Selassie was on a state visit to Brazil, his Kebur Zabagna (Imperial Guard) forces staged an unsuccessful coup, briefly proclaiming Haile Selassie's eldest son Asfa Wossen as emperor. The regular army and police forces crushed the coup d'état. The coup attempt lacked broad popular support, was denounced by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and was unpopular with the army, air force and police. Nonetheless, the effort to depose the emperor had support among students and the educated classes.[163] The coup attempt has been characterized as a pivotal moment in Ethiopian history, the point at which Ethiopians "for the first time questioned the power of the king to rule without the people's consent".[164] Student populations began to empathize with the peasantry and poor and advocate on their behalf.[164] The coup spurred Haile Selassie to accelerate reform, which was manifested in the form of land grants to military and police officials.

The emperor continued to be a staunch ally of the West, while pursuing a firm policy of decolonization in Africa, which was still largely under European colonial rule. The United Nations conducted a lengthy inquiry regarding Eritrea's status, with the superpowers each vying for a stake in the state's future. Britain, the administrator at the time, suggested Eritrea's partition between Sudan and Ethiopia, separating Christians and Muslims. The idea was instantly rejected by Eritrean political parties, as well as the UN.

A UN plebiscite voted 46 to 10 to have Eritrea be federated with Ethiopia, which was later stipulated on 2 December 1950 in resolution 390 (V). Eritrea would have its own parliament and administration and would be represented in what had been the Ethiopian parliament and would become the federal parliament.[165] Haile Selassie would have none of the European attempts to draft a separate Constitution under which Eritrea would be governed, and wanted his own 1955 Constitution protecting families to apply in both Ethiopia and Eritrea. In 1961 the 30-year Eritrean Struggle for Independence began, followed by the dissolution of the federation and shutting down of Eritrea's parliament.

In September 1961, Haile Selassie attended the Conference of Heads of State of Government of Non-Aligned Countries in Belgrade, FPR Yugoslavia. This is considered to be the founding conference of the Non-Aligned Movement.

In 1961, tensions between independence-minded Eritreans and Ethiopian forces culminated in the Eritrean War of Independence. Eritrea's elected parliament voted to become the fourteenth province of Ethiopia in 1962.[166][167] The war would continue for 30 years; first Haile Selassie, then the Soviet-backed junta that succeeded him, attempted to retain Eritrea by force.

In 1963, Haile Selassie presided over the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the precursor of the continent-wide African Union (AU). The new organization would establish its headquarters in Addis Ababa. In May of that year, Haile Selassie was elected as the OAU's first official chairperson, a rotating seat. Along with Modibo Keïta of Mali, the Ethiopian leader would later help successfully negotiate the Bamako Accords, which brought an end to the border conflict between Morocco and Algeria. In 1964, Haile Selassie would initiate the concept of the United States of Africa, a proposition later taken up by Muammar Gaddafi.[168]

On 4 October 1963, Haile Selassie addressed the General Assembly of the United Nations[169][170] referring in his address to his earlier speech to the League of Nations:

Twenty-seven years ago, as Emperor of Ethiopia, I mounted the rostrum in Geneva, Switzerland, to address the League of Nations and to appeal for relief from the destruction which had been unleashed against my defenceless nation, by the fascist invader. I spoke then both to and for the conscience of the world. My words went unheeded, but history testifies to the accuracy of the warning that I gave in 1936. Today, I stand before the world organization which has succeeded to the mantle discarded by its discredited predecessor. In this body is enshrined the principle of collective security which I unsuccessfully invoked at Geneva. Here, in this Assembly, reposes the best – perhaps the last – hope for the peaceful survival of mankind.[171]

On 25 November 1963, the emperor was among other heads of state, including France's President Charles de Gaulle, who traveled to Washington, D.C., and attended the funeral of assassinated President John F. Kennedy. Haile Selassie was the only African head of state to attend the funeral.[172]

In 1966, Haile Selassie attempted to replace the historical tax system with a single progressive income tax, which would significantly weaken the nobility who had previously avoided paying most of their taxes.[173] Even with alterations, this law led to a revolt in Gojjam, which was repressed although enforcement of the tax was abandoned. Having achieved its design in undermining the tax, the revolt encouraged other landowners to defy Haile Selassie.

While he had fully approved and assured Ethiopia's participation in UN-approved collective security operations, including Korea and Congo, Haile Selassie drew a distinction between it and the non-UN-approved foreign intervention in Indochina, consistently deploring it as needless suffering and calling for the Vietnam War to end on several occasions. At the same time he remained open toward the United States and commended it for making progress with African Americans' Civil Rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s, while visiting the US several times during these years.

In 1967, he visited Montréal, Canada, to open the Ethiopian Pavilion at the Expo '67 World's Fair where he received great acclaim among other World leaders there for the occasion.

Student unrest became a regular feature of Ethiopian life in the 1960s and 1970s. Communism took root in large segments of the Ethiopian intelligentsia, particularly among those who had studied abroad and had thus been exposed to radical and left-wing sentiments that were becoming popular in other parts of the globe.[163] Resistance by conservative elements at the Imperial Court and Parliament, and by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, made Haile Selassie's land reform proposals difficult to implement, and also damaged the standing of the government, costing Haile Selassie much of the goodwill he had once enjoyed. This bred resentment among the peasant population. Efforts to weaken unions also hurt his image.[citation needed] As these issues began to pile up, Haile Selassie left much of domestic governance to his Prime Minister, Aklilu Habte Wold, and concentrated more on foreign affairs.

1970s

Outside of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie continued to enjoy enormous prestige and respect. As the longest-serving head of state in power, he was often given precedence over other leaders at state events, such as the state funerals of John F. Kennedy and Charles de Gaulle, the summits of the Non-Aligned Movement, and the 1971 celebration of the 2,500 years of the Persian Empire. In 1970 he visited Italy as a guest of President Giuseppe Saragat, and in Milan he met Giordano Dell'Amore, President of Italian Savings Banks Association. He visited China in October 1971, and was the first foreign head of state to meet Mao Zedong following the death of Mao's designated successor Lin Biao in a plane crash in Mongolia.

Human rights in Ethiopia under Haile Selassie's regime were poor.[citation needed] Civil liberties and political rights were low with Freedom House giving Ethiopia a "Not Free" score for both civil liberties and political rights in the last years of Haile Selassie's rule.[174] Although some sources state that common human rights abuses included imprisonment and torture of political prisoners and very poor prison conditions;[17] the Emperor was known for pardoning hundreds of prisoners at a time and there were no more than ten political prisoners during his entire reign.[175] The Imperial Ethiopian Army also carried out a number of atrocities while fighting the Eritrean separatists. This was due to frustrated soldiers, some of them ethnically Eritrean, who broke ranks with the military, disobeyed laws and began illegally destroying Eritrean villages that supported the rebels.[176] There were a number of mass killings of hundreds of civilians during the war in the late 1960s and early '70s.[177][178][179][180] An investigation into the atrocities was started by Haile Selassie's regime and some officials were arrested. However six days after the investigation began the government collapsed when the Emperor was deposed on 12 September 1974.[176]

Wollo famine

Famine—mostly in Wollo, north-eastern Ethiopia, as well as in some parts of Tigray—is estimated to have killed 40,000 to 80,000 Ethiopians[15][181] between 1972 and 1974. A BBC News report[182] has cited a 1973 estimate that 200,000 deaths occurred, based on a contemporaneous estimate from the Ethiopian Nutrition Institute. While this figure is still repeated in some texts and media sources, it was an estimate that was later found to be "over-pessimistic".[184] Although the region is infamous for recurrent crop failures and continuous food shortage and starvation risk, this episode was remarkably severe. A 1973 production of the ITV programme The Unknown Famine by Jonathan Dimbleby[185][186] relied on the unverified estimate of 200,000 dead,[182][187] stimulating a massive influx of aid while at the same time destabilizing Haile Selassie's regime.[181]

Against that background, a group of dissident army officers instigated a creeping coup against the emperor's faltering regime. To guard against a public backlash in favour of Haile Selassie (who was still widely revered), they contrived to obtain a copy of The Unknown Famine which they intercut with images of Africa's grand old man presiding at a wedding feast in the grounds of his palace. Retitled The Hidden Hunger, this film noir was shown around the clock on Ethiopian television to coincide with the day that they finally summoned the nerve to seize the emperor himself.

— Jonathan Dimbleby, "Feeding on Ethiopia's famine"[188]

Some reports suggest that the emperor was unaware of the famine's extent,[176][182] while others incorrectly assert that he was well aware of it.[189][190] In addition to the exposure of attempts by corrupt local officials to cover up the famine from the imperial government, the Kremlin's depiction of Haile Selassie's Ethiopia as backwards and inept (relative to the purported utopia of Marxism-Leninism) contributed to the popular uprising that led to its downfall and the rise of Mengistu Haile Mariam.[191] The famine and its image in the media undermined the government's popular support, and Haile Selassie's once unassailable personal popularity fell.[192]

The crisis was exacerbated by military mutinies and high oil prices, the latter a result of the 1973 oil crisis. The international economic crisis triggered by the oil crisis caused the costs of imported goods, gasoline, and food to skyrocket, while unemployment spiked.[158]

Revolution

In February 1974, four days of serious riots in Addis Ababa against a sudden economic inflation left five dead. The emperor responded by announcing on national television a reduction in petrol prices and a freeze on the cost of basic commodities. This calmed the public, but the promised 33% military wage hike was not substantial enough to pacify the army, which then mutinied, beginning in Asmara and spreading throughout the empire. This mutiny led to the resignation of Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold on 27 February 1974.[193] Haile Selassie again went on television to agree to the army's demands for still greater pay, and named Endelkachew Makonnen as his new Prime Minister. Despite Endalkatchew's many concessions, discontent continued in March with a four-day general strike that paralyzed the nation.

Imprisonment

The Derg, a committee of low-ranking military officers and enlisted men, set up in June to investigate the military's demands, took advantage of the government's disarray to depose the 82-year-old Haile Selassie on 12 September.[194] General Aman Mikael Andom, a Protestant of Eritrean origin,[193] served briefly as provisional head of state pending the return of Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, who was then receiving medical treatment abroad. Haile Selassie was placed under house arrest briefly at the 4th Army Division in Addis Ababa.[193] At the same time, most of his family was detained at the late Duke of Harar's residence in the north of the capital. The last months of the emperor's life were spent in imprisonment, in the Grand Palace.[195] Reportedly, his mental condition was such that he believed he was still Emperor of Ethiopia.[citation needed]

Later, most of the imperial family was imprisoned in the Addis Ababa prison Kerchele, also known as "Alem Bekagne", or "I've had Enough of This World". On 23 November 60 former high officials of the imperial government were executed by firing squad without trial,[196] which included Haile Selassie's grandson Iskinder Desta, a rear admiral, as well as General Andom and two former prime ministers.[195][197] These killings, known to Ethiopians as "Bloody Saturday", were condemned by Crown Prince Asfa Wossen; the Derg responded to his rebuke by revoking its acknowledgment of his imperial legitimacy, and announcing the end of the Solomonic dynasty.[196]

Death and interment

On 28 August 1975, state media reported that Haile Selassie had died on 27 August of "respiratory failure" following complications from a prostate examination followed up by a prostate operation.[198] Dr. Asrat Woldeyes denied that complications had occurred and rejected the government version of his death. The prostate operation in question apparently had taken place months before the state media claimed, and Haile Selassie had apparently enjoyed strong health in his last days.[199] In 1994, an Ethiopian court found several former military officers guilty of strangling the emperor in his bed in 1975. Three years after the military socialist Derg regime was overthrown[200] the court charged them with genocide and murder, claiming that it had obtained documents attesting to a high-level order from the military regime to assassinate Haile Selassie for leading a "feudal regime".[10] Documents have been widely circulated online showing the Derg's final assassination order and bearing the military regime's seal and signature.[201][202] The veracity of these documents has been corroborated by multiple former members of the military Derg regime.[203][204]

The Soviet-backed People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, the Derg's successor, fell in 1991. In 1992, Haile Selassie's bones were found under a concrete slab on the palace grounds,[205] Haile Selassie's coffin rested in Bhata Church for nearly a decade, near his great-uncle Menelik II's resting place.[206] On 5 November 2000, the Ethiopian Orthodox church gave him a funeral, but the government refused calls to declare the ceremony an official imperial funeral.[206]

Prominent Rastafari figures such as Rita Marley participated in the funeral, but most Rastafari rejected the event and refused to accept that the bones were Haile Selassie's remains. There is some debate within the Rastafari movement whether he actually died in 1975.[207]

Descendants

Haile Selassie had six children with Menen Asfaw: Princess Tenagnework, Crown Prince Asfaw Wossen, Princess Zenebework, Princess Tsehai, Prince Makonnen, and Prince Sahle Selassie.

There is some controversy about the maternity of Haile Selassie's eldest daughter, Princess Romanework. While the living members of the royal family state that Romanework is the eldest daughter of Empress Menen,[208] it has been asserted that Princess Romanework is actually the daughter of a previous union of the emperor with a Woizero Altayech.[209] This may be a nickname she used, as nobleman Blata Merse Hazen Wolde Kirkos, a contemporary source prominent in both the Imperial Court and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, names her Woizero Woinetu Amede and mentions her attending the wedding of her daughter to Dejazmatch Beyene Merid in a firsthand account in his book about the years before the Italian occupation. The emperor's autobiography makes no mention of this previous marriage or having fathered children with anyone other than Empress Menen. However, he mentions the death of this daughter in captivity at Turin.

Prince Asfaw Wossen was first married to Princess Wolete Israel Seyoum and then following their divorce to Princess Medferiashwork Abebe. Prince Makonnen was married to Princess Sara Gizaw. Prince Sahle Selassie was married to Princess Mahisente Habte Mariam. Princess Tenagnework first married Ras Desta Damtew, and after she was widowed, married Ras Andargachew Messai. Princess Zenebework married Dejazmatch Haile Selassie Gugsa. Princess Tsehai married Lt. General Abiye Abebe.

A public rift between some of the descendants ensued when the late Emperor's Patek Philippe watch came up for auction in 2017. In the end it was sold for $2.9 million by leading international auction house Christie's.[210]

Rastafari messiah

…Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God.

— Psalm 68:31

Today, Haile Selassie is worshipped as God incarnate[211] among some followers of the Rastafari movement (taken from Haile Selassie's pre-imperial name Ras—meaning Head, a title looking equivalent to Duke—Tafari Makonnen), which emerged in Jamaica during the 1930s under the influence of Leonard Howell, a follower of Marcus Garvey's "African Redemption" movement. He is viewed as the messiah who will lead the peoples of Africa and the African diaspora to freedom.[212] His official titles are Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah and King of Kings of Ethiopia, Lord of Lords and Elect of God, and his traditional lineage is thought to be from Solomon and Sheba.[213] These notions are perceived by Rastafari as confirmation of the return of the messiah in the prophetic Book of Revelation in the New Testament: King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, and Root of David. Rastafari faith in the incarnate divinity of Haile Selassie[214] began after news reports of his coronation reached Jamaica,[215] particularly via the two Time magazine articles on the coronation the week before and the week after the event. Haile Selassie's own perspectives permeate the philosophy of the movement.[215][216]

In 1961, the Jamaican government sent a delegation composed of both Rastafari and non-Rastafari leaders to Ethiopia to discuss the matter of repatriation, among other issues, with the emperor. He reportedly told the Rastafari delegation (which included Mortimer Planno), "Tell the Brethren to be not dismayed, I personally will give my assistance in the matter of repatriation."[217]

Haile Selassie visited Jamaica on 21 April 1966, and approximately one hundred thousand Rastafari from all over Jamaica descended on Palisadoes Airport in Kingston to greet him.[215] Spliffs[218] and chalices[219] were openly[220] smoked, causing "a haze of ganja smoke" to drift through the air.[221][222][223] Haile Selassie arrived at the airport but was unable to come down the airplane's mobile steps, as the crowd rushed the tarmac. He then returned into the plane, disappearing for several more minutes. Finally, Jamaican authorities were obliged to request Ras Mortimer Planno, a well-known Rasta leader, to climb the steps, enter the plane, and negotiate the emperor's descent.[224] Planno re-emerged and announced to the crowd: "The Emperor has instructed me to tell you to be calm. Step back and let the Emperor land".[225] This day is widely held by scholars to be a major turning point for the movement,[226][227][228] and it is still commemorated by Rastafari as Grounation Day, the anniversary of which is celebrated as the second holiest holiday after 2 November, the emperor's Coronation Day.

From then on, as a result of Planno's actions, the Jamaican authorities were asked to ensure that Rastafari representatives were present at all state functions attended by the emperor,[227][228] and Rastafari elders also ensured that they obtained a private audience with the emperor,[227] where he reportedly told them that they should not emigrate to Ethiopia until they had first liberated the people of Jamaica. This dictum came to be known as "liberation before repatriation".

Haile Selassie defied expectations of the Jamaican authorities[229] and never rebuked the Rastafari for their belief in him as God. Instead, he presented the movement's faithful elders with gold medallions—the only recipients of such an honor on this visit.[230][231] During PNP leader (later Jamaican Prime Minister) Michael Manley's visit to Ethiopia in October 1969, the emperor allegedly still recalled his 1966 reception with amazement, and stated that he felt that he had to be respectful of their beliefs.[232] This was the visit when Manley received the Rod of Correction or Rod of Joshua as a present from the emperor, which is thought to have helped him to win the 1972 election in Jamaica.

Rita Marley, Bob Marley's wife, converted to the Rastafari faith after seeing Haile Selassie on his Jamaican trip. She claimed in interviews (and in her book No Woman, No Cry) that she saw a stigmata print on the palm of Haile Selassie's hand as he waved to the crowd which resembled the markings on Christ's hands from being nailed to the cross—a claim that was not supported by other sources, but was used as evidence for her and other Rastafari to suggest that Haile Selassie I was indeed their messiah.[233] She was also influential in the conversion of Bob Marley, who then became internationally recognized. As a result, Rastafari became much better known throughout much of the world.[234] Bob Marley's posthumously released song "Iron Lion Zion" refers to Haile Selassie.

Haile Selassie's position

In a 1967 recorded interview with the CBC, Haile Selassie denied his alleged divinity. In the interview Bill McNeil says: "there are millions of Christians throughout the world, your Imperial Majesty, who regard you as the reincarnation of Jesus Christ." Haile Selassie replied in his native language:

I have heard of that idea. I also met certain Rastafarians. I told them clearly that I am a man, that I am mortal, and that I will be replaced by the oncoming generation, and that they should never make a mistake in assuming or pretending that a human being is emanated from a deity.[235]

For many Rastafari the CBC interview is not interpreted as a denial of his divinity. According to Robert Earl Hood, Haile Selassie neither denied nor affirmed his divinity either way.[236] In Reggae Routes: The Story of Jamaican Music, Kevin Chang and Wayne Chen note:

It's often said, though no definite date or source is ever cited, that Haile Selassie himself denied his divinity. Former senator and Gleaner editor, Hector Wynter, tells of asking him, during his visit to Jamaica in 1966, when he was going to tell Rastafarians he was not God. "Who am I to disturb their belief?" replied the emperor.[229][237]

After his return to Ethiopia, he dispatched Archbishop Abuna Yesehaq Mandefro to the Caribbean and according to Yesehaq this was done to help draw Rastafari and other West Indians to the Ethiopian church.[238][239] However some sources suggest that certain islanders and their leaders were resenting the services of their former colonial churches and vocalized their interest of establishing the Ethiopian church in the Caribbean to which the Emperor obliged.[240]

In 1969, Michael Manley visited the Emperor at his palace in Addis Ababa before his election as Prime Minister of Jamaica in 1972. Haile Selassie spoke about his visit to Jamaica in 1966 and told Manley that he was totally dumbfounded by the Rastafarians' beliefs but that he had to be respectful of them.[241]

In 1948, Haile Selassie donated 500 hectares of land at Shashamane, 250 kilometres (160 mi) south of Addis Ababa, to the Ethiopian World Federation Incorporated for the use of people of African descent who supported Ethiopia during the war, particularly those from the West.[242] Numerous Rastafari families settled there and still live as a community to this day.[243] Haile Selassie granted Rastafarians land on traditional Oromo domain hence today the Rastas are viewed by the locals as invaders.[244][245][246]

Titles and styles

- 23 July 1892 – 1 November 1905: Lij Tafari Makonnen[30][247]

- 1 November 1905 – 11 February 1917: Dejazmach Tafari Makonnen[30][35]