Pencak silat: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| logocaption = Pencak silat |

| logocaption = Pencak silat |

||

| logosize = 200px |

| logosize = 200px |

||

| image = |

|||

| image =[[File:DSC 3099 wikimedia2020 deni dahniel atraksi silek minagkabau.jpg|257px]] |

|||

| imagecaption = |

|||

| imagecaption = Pencak silat of ''Silek Minangkabau'' duel, one of the combatants is using [[kerambit]] |

|||

| imagesize = |

| imagesize = |

||

| name = Pencak silat |

| name = Pencak silat |

||

Revision as of 09:07, 9 October 2022

Pencak silat | |

| Also known as | Pencak silat Indonesia |

|---|---|

| Focus | Self-defense |

| Hardness | Full-contact, semi-contact, light-contact |

| Country of origin | Indonesia |

| Famous practitioners | Iko Uwais, Yayan Ruhian, Cecep Arif Rahman |

| Olympic sport | No |

| Traditions of Pencak Silat | |

|---|---|

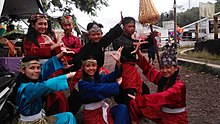

Two men performing Silek lanyah (one of pencak silat), traditional martial arts of the Minangkabau people in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Silek lanyah is always performed in a muddy paddy field. | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Criteria | Oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage, performing arts, social practices, rituals and festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe, and traditional craftsmanship |

| Reference | 1391 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | (14th session) |

| List | Representative List |

Silek (inc. Silat Harimau), Mancak, Ulu Ambek/Alau Ambek, Sewah, Galuik (West Sumatera); Bepencak (Bangka); Pencé (Banten); Silat (West Java, Special Capitol Region of Jakarta, Banten, Central Java, East Java, Special Region of Yogyakarta, Bali); Penca, Amengan, Ulinan, Maénpo, Usik, Heureuy (West Java); Maen Pukulan (Special Capitol Region of Jakarta); Akeket, Okol, Penthengan (Madura, East Java); Encak, Pencakan (East Java); Pencak (Special Region of Yogyakarta, East Java, Bali); Kuntau (West Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan, South Kalimantan, East Kalimantan); Langga (Gorontalo), Amanca (South Sulawesi); Pakuttau (West Sulawesi), Mencak, Kuntuh (West Nusa Tenggara). | |

| Highest governing body | International Pencak Silat Federation (IPSF) |

|---|---|

| First played | Indonesia |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Dependent on type of Pencak silat |

| Team members | Individuals or Team |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Type | Martial art |

| Venue | Fighting arena |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide, Asia primarily |

| Olympic | (Unofficial Sport) |

| World Championships | World Pencak Silat Championships |

Pencak silat (Indonesian pronunciation: [ˈpent͡ʃaʔ ˈsilat]; in Western writings sometimes spelled "pentjak silat" or phonetically as "penchak silat") is an umbrella term for a class of related Indonesian martial arts.[1][2] In neighbouring countries, the term usually refers to professional competitive silat.[3] It is a full-body fighting form incorporating strikes, grappling and throwing in addition to weaponry. Every part of the body is used and subject to attack. Pencak silat was practiced not only for physical defense but also for psychological ends.[4] There are hundreds of different pencak silat styles (aliran) and schools (perguruan) which tend to focus either on strikes, joint manipulation, weaponry, or some combination thereof.

The International Pencak Silat Federation (IPSF), or PERSILAT (Persekutuan Pencak Silat Antarabangsa), is the international pencak silat governing organization and the only pencak silat organisation recognised by the Olympic Council of Asia.[5] The organisation was established on 11 March 1980 in Jakarta and consists of the national organisations of Brunei Darussalam (Persekutuan Silat Kebangsaan Brunei Darussalam) (PERSIB), Indonesia (Ikatan Pencak Silat Indonesia) (IPSI), Malaysia (Persekutuan Silat Kebangsaan) (PESAKA), and Singapore (Persekutuan Silat Singapura) (PERSISI).[6][7]

Pencak silat is included in the Southeast Asian Games and other region-wide competitions. Pencak silat made its debut in the 1987 Southeast Asian Games and 2018 Asian Games, both held in Indonesia.[8]

Pencak silat was recognized as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity from Indonesia by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) on December 12, 2019.[9]

Etymology

Silat is a collective word for a class of indigenous martial arts from the geo-cultural area of Indonesia, more precisely in the Indonesian Archipelago, a region known locally as Nusantara.[10] The origin of the word silat is uncertain. The Malay term silat is linked to Minangkabau word silek. Due to Sumatran origin of the Malay language, the Sumatran origin of the term is likely.[10] The term the word Pencak comes from the Sundanese Penca, in the western part of Java is the origin of this martial art and has been played by the Sundanese for centuries, until it exists in Central and East Java to be studied.[11]

Although the word silat is widely known throughout much of Southeast Asia, the term pencak silat is used mainly in Indonesia. "Pencak silat" was chosen in 1948 as a unifying term for the Indonesian fighting styles. It was a compound of the two most commonly used words for martial arts in Indonesia. Pencak was the term used by the Sundanese in western part of Java and also in the Central Java and East Java,[12] while silat was used in Sumatra, Malay Peninsula and Borneo. In Minang usage, pencak and silat are seen as being two aspects of the same practice. Pencak is the essence of training, the outward aspect of the art which a casual observer is permitted to witness as performance. Silat is the essence of combat and self-defense, the true fighting application of the techniques which are kept secret from outsiders and not divulged to students until the guru deems them ready. While other definitions exist, all agree that silat cannot exist without pencak, and pencak without silat skills is purposeless.[13]

Some believe that pencak comes from the Sanskrit word pancha meaning five, or from the Chinese term pencha or pungcha which implies parrying or deflecting, and striking or pressing.[14]

Other terms may be used in particular dialects such as silek, penca, mancak, maen po or main-po.

Dutch East Indies newspapers of the colonial era recorded the terms for martial arts under Dutch spellings. These include silat, pencak (spelled in Dutch as "pentjak"), penca ("pentjah"), mancak ("mentjak"), manca ("mentjah"), and pukulan ("poekoelan").[15] In 1881 a magazine calls mancak a Batak fencing game "with long swords, daggers or wood (mentjah)"[16] These papers described mancak as Malay (Maleische) suggesting that the word originates in Sumatra.[17] These terms were used separately from silat in the Dutch East Indies.[18] The terms pukulan or main pukulan (spelled "maen poekoelan" in Dutch) referred to the fighting systems of Jakarta but was also used generally for the martial arts of other parts of Indonesia such as Sumatra and Lombok.[15] Believed to be a Betawi term, it derives from the words for play (main) and hit (pukulan).

History

Origins

The oral history of Indonesia begins with the mythical legend about the arrival of Aji Saka (lit. primordial king) from India to Java. At the request of the local people, he successfully killed the monarch Dewata Cengkar of Medang Kamulan in battle and took his place as ruler. This story traditionally marks the rise of Java and the dawn of its Dharmic civilisation. The tale also illustrates the influence India had on Indonesian and Southeast Asian culture in general. Aji Saka is shown to be a fighter and swordsman, while his servants are also depicted as fighting with daggers. The Indian method of knife-duelling was adapted by the Batak and Bugis-Makassar peoples. Ancient Indonesian art from this period also depicts warriors mounted on elephants wielding Chinese weapons such as the jian or straight double-edge sword, which is still used in Java.

The earliest evidence of pencak silat being taught in a structured manner comes from 6th-century[19] in Minangkabau Highlands of West Sumatra. The Minangkabau had a clan-based feudal government. Military officers called hulubalang acted as bodyguards to the king or yam tuan. Minang warriors served without pay. The plunder was divided among them according to military merit, so fighters strove to outdo each other. They were skilled horsemen with the native pony and also expert bladesmiths, producing arms both for their own use and for export to Aceh. Traditional Minang society was based around matrilineal custom, so pencak silat was commonly practiced by women.[1] As pencak silat became widespread in Srivijaya, the empire was defeated by the Tamil Cholas of south India in the 13th century. The Tamil stick fighting art of silambam is still the most common Indian fighting system in Southeast Asia today.

During the 13th century, Ken Arok, a thug turned into a self made hero and ruler, took over the power from Kediri Kingdom and established the Rajasa Dynasty. This is pretty much reflected the jago (people's champion) culture of ancient Java, where a self made cunning man skillful in martial arts, could rally supports and took over the kingdom.[20] His successor, the warrior-king Kertanegara of Singhasari conquered the Melayu Kingdom, Maluku Islands, Bali, and other neighbouring areas. From 1280 to 1289, Kublai Khan sent envoys demanding that Singhasari submit to the Khan as Jambi and Melayu had already done, but Kertanegara responded defiantly by scarring the last envoy's face. Kublai Khan retaliated by sending a punitive expedition of 1000 junks to Java, but Kertanegara had already been killed by a vassal in Kediri before the Yuan force arrived. His son-in-law Raden Wijaya replaced Kertanegara as leader and allied himself with the arriving Mongol army. With their help Raden Wijaya was able to defeat the Kediri forces. With his silat-trained warriors, Raden Wijaya then turned on the Mongols so that they fled back to China. The village he founded became the Majapahit empire. This was the first empire to unite all of Indonesia's major islands, and pencak silat reached its technical zenith during this period. In Majapahit, pencak silat became the specialised property of the nobility and its advanced secrets were hidden from commoners.[1]

Colonial era

The lucrative spice trade eventually brought colonists from Europe, first the Portuguese followed by the Dutch and British. The Dutch East India Company became the dominant power and established full colonial rule in Indonesia. Local revolts and uprisings were common, but all were suppressed by the Dutch armed with guns and cannons. The Dutch brought in even more Chinese workers to Indonesia, which brought a greater variety of local kuntao systems. But while the Europeans could effectively overtake and hold the cities, they found it impossible to control the smaller villages and roads connecting them. Indonesians took advantage of this, fighting an underground war through guerilla tactics. Local weapons were recorded as being used against the Dutch, particularly knives and edged weapons such as the golok, parang, kris and klewang.

During the 17th century, the Bugis people of Sulawesi allied with the Dutch colonists to destroy Mangkasara rule over the surrounding area. While this increased Bugis power in the southwest, Dutch rule deprived seafaring merchants like the Bugis of their traditional employment. As a result, these communities increasingly turned to piracy during the 17th-18th centuries. Not only was pencak silat practiced by the pirates, but new styles were created to combat them.

During the Dutch colonial era of the 18th and 19th century, the exploitative social and economic condition of the colony created the culture of the jago or local people's champion regarded as thugs and bandits by the colonial administration. Parallels can be seen in the jawara of Priangan, jagoan of Betawi, and warok in the Ponorogo region of East Java. The most infamous band of jagoan was the 19th century Si Pitung and Si Jampang, experts in Silat Betawi. Traditionally depicted as Robin Hood-like figures, they upheld justice for the common man by robbing from the rich who acquired power and status by collaborating with the colonists. The jago were despised by the Dutch authorities as criminals and thieves but were highly respected by the native pribumi and local Chinese.

Modern era

Conflict with the European rulers provided an impetus for the proliferation of new styles of pencak silat, now founded on the platform of nationalism and the desire for freedom from colonisation. The Indonesian Pencak Silat Association (IPSI) was founded in 1948 to bring all of Indonesia's pencak silat under a single administration. The world's oldest nationwide silat organisation, its basis is that all pencak silat is built on a common source, and that less functional styles must give way to the technically superior. IPSI has avoided the tendency of modern martial arts that gravitate towards sport. The resistance to sport has lessened over time, however, and sparring in particular has become less combative. While nominally an Indonesian organisation, many of the rules and regulations outlined by IPSI have become the de facto standard for silat competitions worldwide. Indo-Dutch Eurasians who first began practicing pencak silat in the 20th century[15] spread the art to the west in the late 20th century.

Today pencak silat is one of the extra-curricular activities taught in Indonesian schools. It is included as a combat sport in local, national and international athletic events such as the SEA Games (South-East Asia Games) and Indonesia's National Sports Week (Pekan Olahraga Nasional). Since 2012, the Pencak Malioboro Festival has been held annually and features demonstrations by the biggest silat schools in Indonesia. The art features prominently in the Hollywood blockbuster John Wick 3, with masters Yayan Ruhian and Cecep Arif Rahman appearing against Wick in the penultimate fight, and the animated series Code Lyoko, in which multiple episodes show protagonists Yumi Ishiyama and Ulrich Stern training in and utilizing the fighting style among other characters.

Weapons

As with most ancient fighting arts, pencak silat historically prioritized weapons over unarmed combat. While this is usually not the case today, all pencak silat schools include weapons to some degree of importance. While pencak silat includes a wide array of weapons, the following are considered standard in all classical styles. In addition to these, many systems include a specialty or "secret" weapon taught only to advanced students.

- Toya: Staff usually made of rattan but sometimes wood or metal. Typically measures 5–6 feet long and 1.5-2 inches in diameter.

- Tombak/Lembing: Spear or javelin made of bamboo, steel or wood that sometimes has horsehair attached near the blade.

- Parang: Machete-like chopper, ranging from 10 to 36 inches long

- Golok: Heavy cleaver measuring 10-20 inches long. The blade is heaviest in the centre

- Pisau: Any short-bladed knife

- Kris: Double-edged dagger made by folding different types of metal together and then washing it in acid.

- Celurit: A sickle, commonly used in farming, cultivation and harvesting of crops.

- Tongkat/Galah: Short stick or cudgel

- Pedang: Sword, most often single-edged and either straight or slightly curved. Usually measures 15-35 inches overall with a blade upward of 10 inches long

- Klewang: Single-edge longsword with a protruding notch near its tip

- Chabang: Short-handled trident, literally meaning "branch"

- Selendang: A silk that can be used for strangling, grappling and whipping

- Kerambit: A small curved knife resembling a claw.

Styles and schools

Over 150 styles of pencak silat are recognised in Indonesia,[21] although the actual number of existing systems is well beyond that. Older methods are typically identified with specific ethno-cultural groups or particular regions.

Minangkabau

The Minangkabau formed the dominant sovereignty in West Sumatra and make up the majority of Sumatran pencak silat systems. These styles may be referred to as silat Minangkabau, silat Padang (lit. field silat), or silek, the local pronunciation of silat. Very few systems in Indonesia have not been influenced by silek, and its techniques form the core of pencak silat throughout Sumatra. It developed as an extension of the original silat Melayu from Riau. Folklore traces this to five masters, namely Ninik Datuak Suri Dirajo from Padang Panjang, Kambiang Utan ("forest goat") from Cambodia, Harimau Campo ("tiger of Champa") from Vietnam, Kuciang Siam ("Siamese cat") from Thailand and Anjiang Mualim ("teacher dog") from Gujarat.[22][23] Stealth and ambush were the preferred Minang war tactics, and they were said to be among the best assassins in the world when dispatched singly. Silek Minangkabau is characterised by its low stances and reliance on kicks and leg tactics. The low stance is said to have developed to offset the chance of falling on slippery ground, common in the rice fields of West Sumatra. The local practice of paddling rafts with the legs strengthened fighters' lower body muscles. Hand and arm movements are fast, honed through an exercise in which the exponent stands across from a partner tossing sharpened sticks or knives. The practitioner must redirect the sticks or knives and send them back at the thrower, using their hands and a minimum of movements with the rest of the body.

There are currently around ten major styles of silek, a few of which like Silek Lintau are commonly practiced even in Malaysia. IPSI recognises Silek Harimau (tiger silek) as among the oldest pencak silat in existence. Silek Harimau, also known as silek kuciang or cat silek, epitomizes the Minang techniques in that it focuses on crouching and kicking from a low position paired with rapid hand attacks. Sitaralak imitates the power of a herd of stampeding elephants. Developed as a counter to silek Harimau, folklore tells that its practitioners were able to fight tigers. Sandang is the counter-system to Sitaralak, which defends against powerful attacks by misdirection. Kumango is another characteristically Minang system in its kicks and footwork. Its frequent thigh-slapping and taiji-like redirection maneuvers indicate both Indian and Chinese influence. Silek Tuo is considered by some to be the oldest Minang system due to its name meaning "old silek", but others claim it traces to the freedom fighter Tuanku Nan Tuo after whom it was named. All the classical pencak silat weapons are used in silek but the most prominent Minang weapons are the pedang (sword), tumbak (spear), karih (dagger), klewang (longsword), sabik (sickle), payung (umbrella), kurambik (claw), and various types of knives. In cultural aspects, Minangkabau randai dance performance often incorporating some of Minang silek movements.

Java

From Srivijaya, pencak silat quickly spread eastward into the Javanese Sailendra and Medang Kingdoms where the fighting arts developed in three geographical regions: West Java, Central Java, and East Java. Today Java is home to more styles of pencak silat than any other Indonesian island, and displays the greatest diversity of techniques. Many Javanese schools such as Perisai Diri and Inti Ombak have been established internationally in Asia, Europe and America. Merpati Putih or "white dove" style was developed in the keraton (royal courts) of 17th century Mataram and was not taught publicly until 1963.[24] Today it is the standard unarmed martial art of the Indonesian National Armed Forces.[25] It includes weapons but focuses more on empty-handed self-defense and the development of internal strength developed through breathing techniques.[26] Pencak silat in Java draws from traditional kejawen and Hindu-Buddhist Javanese beliefs but after Indonesia's independence, some schools have adapted themselves in the context of modern religion.[27] Among the most popular modern styles is the Muslim-directed Tapak Suci. An evasive long-range system, it requires constant movement as the practitioner rotates on their own axis every few seconds. Similarly the [Setia Hati] school is Christian-organised. Rooted in silek Minangkabau of the Padang area, it relies on kicks and footwork while the hands are mainly used defensively for blocking and parrying.[28]

Riau

Much of what constitutes classical Malay culture has its origin in the Riau Archipelago, including the earliest evidence of silat. Referred to as silat Melayu, the regional fighting systems of Riau have influenced nearly the entirety of Indonesian pencak silat, and into neighbouring Singapore and Malaysia. Fighting tactics dating back to the Srivijaya empire persist in Palembang today. Wide stances with the front foot turned slightly inward are typical, developed for fighting on Riau's muddy ground, while also preventing the knee joint from being exposed to frontal kicks. Seizing techniques which grab the arm are common. The most prominent weapons in silat Melayu are the staff (toya) and the spear. Spear forms in Riau usually begin with the blade pointed downward. Staff technique in silat Melayu of the Palembang area is said to be the best in all of Indonesian pencak silat. The weapon is made of wood and usually measures seven feet long. Fixed hand positions with very little sliding along the staff is characteristic of silat Melayu.

Sunda

Java's western region was the first area from which pencak silat spread out of Sumatra. The Sundanese pencak silat of West Java may be called silat Sunda or silat Bandung. In the Sundanese language they are generically referred to as penca (dialect form of pencak), ameng, ulin or maen po (from the word main meaning "play"). Ameng is the more respectful term, while ulin and maen po are of lower speech levels. Sunda systems are easily identified by the prefix ci (spelled "tji" by the Dutch). Pronounced "chi", it comes from the Sundanese word cai meaning river water, alluding to the fact that they were originally developed in river-basin areas. The deep, wide stance and resulting gait attests to this, owing to the practice of carefully placing the feet from a lifted position onto wet ground. Today, systems of Sunda derivation prefixed with ci are found even in the high plateaus and mountain ranges of both West and Central Java. Penca instruction was traditionally done through apprenticeship, wherein prospective students offer to work as a servant in the master's house or a labourer in the rice fields. In exchange for working during the day, the master provides the student's meals and trains during the evening. Penca is characterized by reliance on hand and arm movements for both attack and defense. Compared to other Javanese systems, Sunda styles have less frontal contact with the opponent, instead preferring to evade in a circular manner and attack from the side. In one form of training designed to practice circular evasion, victory is attained simply by touching the opponent's torso. Fasting and mantra were traditionally used to heighten the senses for this purpose.

The oldest styles of penca were based on animals and movements of farming or tending the fields. IPSI recognises Cimacan (tiger style), Ciular (snake style), and Pamonyet (monkey style) as among the oldest existing pencak silat. Cimacan is said to have been created by a Buddhist monk. The most prominent system of West Java is penca Cimande, first taught publicly by a Badui man named Embah Kahir in Cimande village of the Sukabumi area around 1760.[29] Cimande among the isolationist Badui community is said to be much older than Embah Kahir, and is believed by many masters to be the original penca of West Java tracing back to Pakuan Pajajaran. Cimande is a close-quarters system, with the elbows held close to the body. Students begin by learning to fight from a seated position before they are taught footwork. Arms are traditionally conditioned through smashing coconuts, by concentrating the force of the blow into the wrist. Cimande always assumes there is a minimum of three enemies, but advanced students may spar with up to twelve opponents. As a defensive art, Cimande has no lethal techniques. The town of Cianjur - seen as the heartland of Sunda culture - is associated with a few systems, the most prominent of them being Cikalong or bat style. Borrowing its technical base from Cimande, Cikalong was founded by Raden Jayaperbata after meditating in a cave in the Cikalong Kulon village. While Cimande may attack with either the fists or open hands, Cikalong prefers the latter. Prominent Sunda weapons include the toya (staff), cabang (forked truncheon), long-bladed parang (machete) and heavy golok (cleaver). The advanced weapon is the piau or throwing knife.

Betawi

Among the Betawi people of Greater Jakarta, the pencak silat tradition is rooted in the culture of the jagoan or jawara, local champions seen as heroes of the common people. They went against colonial authority and were despised by the Dutch as thugs and bandits. Silat Betawi is referred to in the local dialect as maen pukulan or main pukulan, literally meaning "strike-play". The most well-known schools are Cingkrik, Kwitang, and Beksi. The acrobatic monkey-inspired Cingkrik is likely the oldest, the name implying agile movement. The art is said to trace back to a monkey style of kuntao attributed to Rama Isruna after his wife observed the actions of monkeys. A student of this kuntao named Ki Maing later expanded on the system after a monkey stole his walking stick. Cingkrik is highly evasive; blows are delivered as a counter after parrying or blocking, and usually target the face, throat and groin. Attacks mimic the grabbing and tearing actions of monkeys. Kwitang also employs evasion and some open-hand strikes but its focus is on powerful punches with the fist tightly closed at the moment of impact, mainly targeting the centreline. Force is concentrated into the knuckles of the little and ring finger. Attacks are made with a curved arm; the elbow is never fully extended so as to prevent being caught in a joint lock. Beksi, meaning "defense of four directions", is credited to a man named Lie Cheng Hok. It is distinguishable from other Betawi systems by its close-distance combat style and lack of offensive leg action. Silat Betawi includes all the classical pencak silat weapons, but places particular emphasis on the parang (machete), golok (chopper), toya (staff), and pisau (knife). Kwitang practitioners are said to be the best chabang fighters in Indonesia.[30]

Bali

Following the invasion by Demak, many families of the Majapahit empire fled to Bali. The descendants of the Majapahit were traditionally resistant to outside influence and as a result, the people of Bali often make a distinction between "pure" Balinese pencak silat and styles introduced from outside such as Perisai Diri. The native systems - known locally as pencak - are ultimately rooted in those of Java, and preserve tactics dating back to the Majapahit empire. They are less direct than other styles, characteristically favouring deception over aggression. Hand movements are used to distract, and openings are deliberately exposed to bluff the opponent into attacking. This approach requires that exponents train their flexibility and stamina. As with Balinese warriors of the past, modern pencak practitioners in Bali often wear headbands as part of their uniform.

There are about four main systems considered purely Balinese. The most prominent of these is Bakti Negara, which is firmly rooted in the old local Hindu philosophy of Tri Hita Karana.[31] Another system which has gained prominence is Seruling Dewata meaning "God's flute". Purported to date back to ancient times, it recognizes the Indian Buddhist monk Bodhidharma as the first patriarch, though not its creator. Eka Sentosa Setiti (ESSTI) was the first pencak silat association officially founded in Bali. Created and practiced in the island's south, it draws heavily from southern Saolim kuntao. The primary stance is the ting posture of kuntao, also the main stance of Japanese aikido. ESSTI keeps membership low and does not permit outsiders to view sparring matches. Finally, the Tridharma style is practiced in northern Bali. It utilizes circular hand movements and straight kicks. The ESSTI and Tridharma schools often exchange students so cross-training between the styles is common. All Balinese pencak schools traditionally keep sportive contests and performance to a minimum in order to emphasise combat effectiveness.

Bugis-Makassar

The Bugis (Ugi) and Makassar people (Mangkasara) are two related maritime groups from Sulawesi. The Bugis in particular were renowned navigators and shipbuilders, but also feared as corsairs and slave-traders. Both the Bugis and Makassarese were famous for piracy, though this was more common among the former than the latter. Silat in Sulawesi is closely tied to local animism, and weapons are believed to be imbued with a spirit of their own. Hand and arm movements are designed to be adaptable for use with a knife or with the empty hands. Attacks with the fists or open hands can be modified with a pinching action of the fingers, which has its origin in the pinch-grip of the badik. Bugis styles (silat Ugi) are based on these hand and arm movements and contain only limited kicks, almost all of the linear variety.

Generally, Southwestern Sulawesi area silat is called "Silat Makassar" and include the "Karena Macang" style which name implies "to perform like a tiger". This Style is related with great affinity to Kuntao, Tapu Silat is a highly secretive form revealed only to chosen experts in self-defense and specializes in countering rear sneak attacks which was common in Makassar as The mangrove swamps and rocky inlets along the coasts of Sulawesi served as hiding places for pirates, so silat among the Bugis and Makassar community makes use of and defends against ambush. Experts in the Tapu system are reported to be supersensitive and must not be touched from the rear or while asleep as the consequent reactions produced will be disastrous to the one disturbing them.[32]: 160

Weapons used for all Bugis-Makassar pencak silat include all standard types normally associated with the combative form, but the Cabang, Pisau, and Parang, are used with extraordinary dexterity and skill. Bugis and Makassarese pencak silat forms take into consideration and give heavy emphasis to the use of their special weapon, The Badik. Much of the arm and hand movement practiced empty handed can instantly be converted into knife thrust-and-slash actions by simply picking up such a weapon. Snap-thrust action while on the move and turning the body into a punch which is "screwed into" the target are characteristic of most styles, and, too, are adaptable to the knife. Hands closed or open as a fist, are often modified by a pinching action of the fingers which relates to the Bugis (and sometimes the Makassarese) habit of holding the Badik with a pinch grip. Considerable practice is made with one forearm outer surface in a blocking role while the other one strikes a blow or delivers a knife to the target; the two motions simultaneously. Bugis pencak silat patterns contains less than 15 percent leg action, and those which are used are more linearly oriented than circular in nature; simple forward stepping movement is, of course, exempt, as it is definitely circular. The Horse riding stance employed suggests Chinese influence.[32]: 160

Aceh

Located on Sumatra's northwest coast on the westernmost tip of the archipelago, Aceh was the first port of call for traders sailing the Indian Ocean. Local culture and weapons (particularly knives) show distinct Indian-Muslim derivation. Unlike the more typical rattan shield, the Acehnese buckler is identical to the Indian dhal (shield), made from metal and with five or seven knobs on the surface. The Acehnese are recorded by both Indonesian and European sources as being the most warlike people in all of Sumatra, and this is reflected in the highly-aggressive nature of their pencak silat. Acehnese pencak silat borrows its foundation from silat Melayu and silek Minangkabau, particularly the arm-seizing techniques of the former and the ground-sitting postures of the latter. Bladed weaponry is favoured, specifically knives and swords. The primary weapon is the rencong, an L-shaped dagger used mainly for thrusting but also for slashing. The kris is used as well but the native rencong takes precedence.

Batak

Batak land is situated between the Minangkabau to the south and Aceh to the north, and the culture shows both Indian and Chinese influence. The word Batak refers to a number of ethnic groups originally from the mountains of North Sumatra. The term typically refers to the Toba Batak while others may explicitly reject that label, preferring to identify themselves by their specific group. Batak silat is known by different names in each community, namely mossak (Toba), moncak (Mandailing), ndikar (Simalungun) and dihar (Karo). Mossak is the most commonly-used due to the Toba being the most numerous. While each style is distinct, all share similar characteristics and weaponry. The Batak were historically in a near-perpetual state of warfare with their neighbours, so warriors trained daily for combat. Training was either done outdoors or in the balai, a building in the kampung specifically made for combat practice. Batak silat is primarily armed, employing such weapons as the spear, single-edge blade, and a short-bladed knife known as the raut. The raut is similar to the badik both in appearance and in its pinch-grip. The most common target is the opponent's midsection. The weapon is held loosely and used in an upward or downward hacking motion. Once the raut has pierced the enemy, the fighter pushes the knife further in with a palm strike. Unarmed techniques are derived from silek Minangkabau, as the kicks and footwork are well-suited to the mountainous Batak country.

Maluku

Pencak silat in the Maluku Islands uses a wide variety of weaponry, some of which are indigenous to the area. The particular specialty of Moluccan silat is the cabang (forked truncheon), pisau (knife), and the wooden or metal galah (staff). The local pedang (sword) is long-bladed and associated with female fighters. On Haruku Island, particular emphasis is placed on one-legged stances. This tactic was developed for fighting in the ankle-deep sands of the islands, allowing the exponent to use both kicking and eye-gouging techniques simultaneously.

Bajau

The Bajau are a seafaring people of Sulawesi. Often nomadic, they were traditionally born and raised on longboats at sea although this is increasingly exceptional as the community has been forced to settle on land in recent decades. Colonial records often mistook them for pirates but - unlike the neighbouring Bugis - the Bajau lacked the organization and technology for piracy. In fact, they more often clashed with pirates than engaging in raids themselves. Their main and often only weapon was the fishing spear, which functioned as a hunting tool on land. The Bajau utilized a wide array of these harpoons as weapons, both thrown and not thrown. Their aim was impeccable, having been honed by fishing and hunting. The spear may be of nibong wood or bamboo, single-pronged or three-pronged, barbed or unbarbed, and tipped with wood or steel. Contact with the southern Philippines and the Sulu sultanate of Borneo allowed the Bajau to acquire other weapons through barter, specifically swords, shields, lances and parang. The most notable Bajau style of pencak silat is centered in Kendari. It is characterized by cross-legged stances and rapid turning, designed to be used in cramped spaces such as boats.

Techniques

Generalizations in pencak silat technique are very difficult; styles and movements are as diverse as the Indonesian archipelago itself. Individual disciplines can be offensive as in Aceh, evasive as in Bali, or somewhere in between. They may focus on strikes (pukulan), kicks (tendangan), locks (kuncian), weapons (senjata), or even on spiritual development rather than physical fighting techniques. Most styles specialize in one or two of these, but still make use of them all to some degree. Certain characteristics tend to prevail in particular geographical regions, as follows:

- Kicks - West Sumatra, North Sumatra

- Hands/Arms - Jakarta, West Java, Sulawesi, Kalimantan

- Grappling - East Java, Sumatra

- Strikes (hands and feet) - Bali, Central Java, Madura

Stances and steps

Students begin by learning basic body stances and steps. Steps or dancing sweep fanlangkah are ways of moving the feet from one point to another during a fight. Pencak silat has several basic steps, known as langkah 8 penjuru or "eight directions of steps". Traditional music is often used as a signal to change body position when practicing langkah.[33]

Langkah are taught in conjunction with preset stances, meant to provide a foundation from which to defend oneself or to launch attacks. The most basic stance is the horse stance (kekuda or kuda-kuda), which provides stability and firm body position by strengthening the quads. Other stances may train the feet, legs, thighs, glutes and back. Other essential stances are the middle stance, the side stance, and the forward stance. The crawling tiger stance, in which the body is kept low in a ground-hugging position, is most common in Minang silek. Stances are essentially a combination of langkah, body posture, and movement. Through their correct application, the practitioner will be able to attack or defend whether standing, crouching, or sitting down, and alternate smoothly from one position to another. When the student has become familiar with stances and langkah, all are combined in forms or jurus.

Forms

Forms or jurus are pre-meditated sets of steps and movements used for practicing proper technique, training agility, and conditioning the body. Repetition of jurus also develops muscle memory so the practitioner can act and react correctly within a split-second in any given combative situation without having to think. Either armed or unarmed, jurus may be solo, one against one, one against several, or even two against more than one. Forms involving more than one practitioner are meant to be performed at the speed of an actual fight. Real weapons are used in the case of armed jurus, but are sometimes unsharpened today. The kembang (lit. "flower") aspect of forms consists of fluid movements with the hands and arms resembling traditional Indonesian dance. As with Korean Taekkyon, these movements are preparation for defending or reversing the opponent's attack. Musical accompaniment provides a metronome to indicate the rhythm of motion. For example, the beat of a drum might signify an attack. Those not aware of the combative nature of these moves often mistake the forms for dancing rather than the formalized training of fighting techniques.[4]

Offense

Pencak silat uses the whole body for attack. The basic strikes are the punch (pukul) and kick (tendang), with many variations in between. Strikes may be performed with the fists, open palms, shins, feet (kaki), elbows (sikut), knees (dengkul or lutut), shoulders (bahu), or the fingers (jari). Even basic attacks may vary depending on style, lineage, and regional origin.[34] Some systems may favour punching with the clenched fist, while others might prefer slapping with the palm of the hand. Other common tactics include feints (tipuan) or deceptive blows used as distraction, sweeping (sapuan) to knock the opponent down, and the scissors takedown (guntingan) which grips the legs around the opponent.

Defense

Defense in pencak silat consists of blocking, dodging, deflecting, and countering. Blocks or tangkisan are the most basic form of defense.[34] Because pencak silat may target any part of the body, blocks can be done with the forearms, hands, shoulders, or shins. Blocking with the elbows may even hurt the attacker. Attacks can also be used defensively, such as kneeing a kicking opponent's leg. Hard blocks, in which force is met with force, are most suitable when fighting opponents of the same strength or lower. Styles that rely on physical power favour this approach, such as Tenaga Dasar. To minimize any damage sustained by the defender when blocking in this way, body conditioning is used such as toughening the forearms by hitting them against hard surfaces. In cases where the opponent is of greater strength, evasion (elakan) or deflections (pesongan) would be used, and are actually preferred in certain styles.

International competitions

The major international competition is Pencak Silat World Championship, organised by PERSILAT.[35] This competition takes place every 2 or 3 years period. More than 30 national teams competed in recent tournaments in Jakarta (2010), Chiang Rai (2012) and Phuket (2015).

Pencak Silat competition categories consist of:[36]

- Tanding (Match) category

- Tunggal (Single) category

- Ganda (Double) category

- Regu (Team) category

List of World Pencak Silat Championships

The championships have been referred to under different names: World Pencak Silat Championships, World Silat Championships or Pencak Silat World Championships.[37]

| Edition | Year | Host | Nations | Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1982 World Pencak Silat Championships | 7 | ||

| 2 | 1984 World Pencak Silat Championships | 9 | ||

| 3 | 1986 World Pencak Silat Championships | 14 | ||

| 4 | 1987 World Pencak Silat Championships | 18 | ||

| 5 | 1988 World Pencak Silat Championships | 18 | ||

| 6 | 1990 World Pencak Silat Championships | 18 | ||

| 7 | 1992 World Pencak Silat Championships | 20 | ||

| 8 | 1994 World Pencak Silat Championships | 19 | ||

| 9 | 1997 World Pencak Silat Championships | 20 | ||

| 10 | 2000 World Pencak Silat Championships | 20 | ||

| 11 | 2002 World Pencak Silat Championships | 19 | ||

| 12 | 2004 World Pencak Silat Championships | 20 | ||

| 13 | 2007 World Pencak Silat Championships | 26 | ||

| 14 | 2010 World Pencak Silat Championships | 32 | 23 | |

| 15 | 2012 World Pencak Silat Championships | 26 | ||

| 16 | 2015 World Pencak Silat Championships | 45 | 24 | |

| 17 | 2016 World Pencak Silat Championships | 40 | 24 | |

| 18 | 2018 World Pencak Silat Championships | 40 | 24 | |

| 19 | 2022 World Pencak Silat Championships | 22 |

All-medal table

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 71 | 30 | 32 | 133 | |

| 2 | 40 | 27 | 18 | 85 | |

| 3 | 19 | 15 | 25 | 59 | |

| 4 | 15 | 11 | 16 | 42 | |

| 5 | 14 | 10 | 22 | 46 | |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 10 | |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 10 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| 11 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Totals (23 entries) | 164 | 102 | 148 | 414 | |

2018 medal table

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 20 | |

| 2 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 13 | |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 15 | |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | |

| 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 11 | |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 7 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Totals (15 entries) | 24 | 24 | 42 | 90 | |

2016 medal table

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 20 | |

| 2 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 18 | |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 11 | |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 12 | |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Totals (17 entries) | 26 | 24 | 39 | 89 | |

2015 medal table

The seven-day event attracted 450 fighters from 40 nations and territories, competing in 24 weight categories in both the combat and performance events (18 combat event and 6 performance event).

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 19 | |

| 2 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 19 | |

| 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 11 | |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 20 | |

| 5 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 11 | |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Totals (7 entries) | 24 | 23 | 36 | 83 | |

Asian Pencak Silat Championships

| Edition | Year | Host | Nations | Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2011 Asian Pencak Silat Championships | 7 | ||

| 2 | 2016 Asian Pencak Silat Championships | 6 | 23 | |

| 3 | 2017 Asian Pencak Silat Championships | 7 | ||

| 4 | 2018 Asian Pencak Silat Championships | 10 |

2011 medal table

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 21 | |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 18 | |

| 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 12 | |

| 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 | |

| 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Totals (7 entries) | 23 | 17 | 33 | 73 | |

2016 medal table

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 23 | |

| 2 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 23 | |

| 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 13 | |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Totals (6 entries) | 23 | 23 | 26 | 72 | |

World Sports School Pencak Silat Championship

The 1st World Sports School Pencak Silat Championship 2016 Singapore

2016 medal table

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Totals (4 entries) | 10 | 11 | 3 | 24 | |

World 5x5 Silat Championship

The 1st World 5X 5 Extreme Skills Silat Championship 2019 Venue: KL, 11-12 Feb 2019 Host: PESAKA Malaysia. The winners came from Suriname and overall best fighter was Chi-jinn Wong Loi Sing, with a clean sweap of 38 - 21 in favor of Suriname. He took home the gold for his team

The 1st Kids & Junior 5x5 Silat Challenge 2017 Venue: KL, 11-12 Mar 2017 Host: PESAKA Malaysia Was taken by Sinada Humidha from Indonesia.

South East Asian Pencak Silat Championship

5th was held in 2015.

Other

The 5th ASIAN Beach Games Venue: Da Nang, 24 Sep - 4 Oct 2016 Host: VPSF Vietnam

The 6th TAFISA International Festival Pencak Silat Venue: Jakarta, 7–8 October 2016 Host: IPSI Indonesia

Image gallery

-

Pencak Silat of Sumatra(Circa 1915)

-

Pencak Silat sword dancing(1939)

-

Pencak Silat sword dancing(1939)

-

Pencak Silat at Fort van der Capellen (circa 1915)

-

Martial arts at east cost of Sumatra (circa 1930)

-

Martial arts at east cost of Sumatra (circa 1930)

See also

- Silat

- Indonesian martial arts

- Silat Harimau

- Silat Melayu

- Bakti Negara

- Cingkrik

- Bokator

- Sikaran

- Escrima

- Muay Thai

References

- ^ a b c Donn F. Draeger (1992). Weapons and fighting arts of Indonesia. Rutland, Vt. : Charles E. Tuttle Co. ISBN 978-0-8048-1716-5.

- ^ "Pencak Silat".

- ^ "Hari Pencak Silat Indonesia". ilmusetiahati.com. 14 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Pencak Silat: Techniques and History of the Indonesian Martial Arts". Black Belt Magazine. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ "Pencak Silat recognized by OCA". ocasia.org. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ^ "PERSILAT was founded on March 11, 1980". berolahraga.net. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ^ Douglas, Ian. "The Politics of Inner Power:The Practice of Pencak Silat in West Java" (PDF). Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ^ "Pencak Silat | Asian Games 2018 Jakarta Palembang". Asian Games 2018 Jakarta Palembang. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ^ "'Pencak silat' given UNESCO intangible world heritage distinction". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ a b Green, Thomas A. (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. p. 324. ISBN 9781598842432.

- ^ Green, Thomas A.; Svinth, Joseph R. (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-243-2.

- ^ Green 2010, p. 324: "Regional appellations are used in the island of Java, for example, penca by the Sundanese (West Java), and pencak by Javanese (Central and Eastern Java)."

- ^ Alexander, Howard; Chambers, Quintin; Draeger, Donn F. (1979). Pentjak Silat: The Indonesian Fighting Art. Tokyo, Japan : Kodansha International Ltd.

- ^ Sheikh Shamsuddin (2005). The Malay Art Of Self-defense: Silat Seni Gayong. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-55643-562-2.

- ^ a b c Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië 20-02-19

- ^ , UITGEGEVEN DOOE HET BATAVIAASCH GENOOTSCHAP VAN KUNSTEN EN WETENSCHAPPEN. ONDEB BEDAGTIE VAN J. E. ALBBECHT. EN D. GEBTH VAN WIJK. Deel XXVI. BATAVIA, W. BEIUNINO & Co. 1881.

- ^ Sumatra-courant : nieuws- en advertentieblad 23-11-1872

- ^ Bataviaasch nieuwsblad 24-04-1928

- ^ "Silek Harimau Minangkabau: the True Martial Art of West Sumatra". Wonderful Indonesia. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ Matanasi, Petrik (2011-07-01). Para Jagoan: Dari Ken Arok sampai Kusni Kasdut (in Indonesian). Trompet Book. ISBN 9786029913118.

- ^ Ika Krismantari (5 December 2012). "Passing on a legacy". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ Thesis: Seni Silat Melayu by Abd Rahman Ismail (USM 2005 matter 188)

- ^ Djamal, Mid. Filsafat dan Silsilah Aliran-Aliran Silat Minangkabau. Penerbit CV. Tropic - Bukittinggi.1986

- ^ "Sejarah Merpati Putih" (in Indonesian). PPS Betako Merpati Putih, Pewaris - Pengurus Pusat. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ "KOARMATIM Siap Tarung" (in Indonesian). Tentara Nasional Indonesia. Archived from the original on June 8, 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ "Merpati Putih" (in Indonesian). PPS Betako Merpati Putih, Pewaris - Pengurus Pusat. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ Uwe Patzold (2011). Self-Defense and Music in Muslim Context in West Java in Divine Inspirations: Music and Islam in Indonesia. Oxford, UK : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538541-0.

- ^ Ilmu Setia Hati (14 September 2020). "Paradigma Ajaran Setia Hati". ilmusetiahati.com. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Cimande". Cimande France. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ Nathalie Abigail Budiman (1 August 2015). "Betawi pencak silat adapts to modern times". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ "Tentang Bakti Negara" (in Indonesian). Bakti Negara. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ a b Draeger, Donn (2012). Weapons & Fighting Arts of Indonesia. Tuttle Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 9781462905096.

- ^ "Pencak Silat Body Basics". Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Pencak Silat Punch and Blocking Techniques". Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "International Pencak Silat Competition Regulations". PERSILAT. 2004. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ competition categories, pencak silat. "Pencak Silat competition categories" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "One Silat".

Further reading

- Quintin Chambers and Donn F. Draeger (1979). Javanese Silat: The Fighting Art of Perisai Diri. ISBN 0-87011-353-4.

- Sean Stark (2007). Pencak Silat Pertempuran: Vol. 1. Stark Publishing. ISBN 978-0-615-13968-5.

- Sean Stark (2007). Pencak Silat Pertempuran: Vol. 2. Stark Publishing. ISBN 978-0-615-13784-1.

- O'ong Maryono (2002). Pencak Silat in the Indonesian Archipelago. ISBN 9799341604.

- Suwanda, Herman (2006). Pencak Silat Through my eyes. Los Angeles: Empire Books. p. 97. ISBN 9781933901039.

- Mason, P.H. (2012) "A Barometer of Modernity: Village performances in the highlands of West Sumatra," ACCESS: Critical Perspectives on Communication, Cultural & Policy Studies, 31(2), 79–90.

External links

- A collection of articles on Pencak Silat history, culture, and techniques

- International Pencak Silat Federation/ Pentjak Silat USA SouthEast Asian Global Martial Arts

- Official website of IPSF/PERSILAT, the Pencak Silat World Federation

- A collection of essays on Pencak Silat by O'ong Maryono.

- A collection of videos and authoritative articles on Combat Pencak Silat by Pendekar Hussein of Silat Sharaf

- Culture Silat (French).