Invasion of Poland: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

→Myths: tanks -> armored vehicles |

||

| Line 172: | Line 172: | ||

[[Image:Powazki wrzesien 1.JPG|thumb|right|260px|Graves of Polish soldiers at [[Powązki Cemetery]], Warsaw.]] |

[[Image:Powazki wrzesien 1.JPG|thumb|right|260px|Graves of Polish soldiers at [[Powązki Cemetery]], Warsaw.]] |

||

There are several common misconceptions regarding the Polish September Campaign: |

There are several common misconceptions regarding the Polish September Campaign: |

||

*''The Polish military was so backward they fought tanks with cavalry'': Although Poland had 11 [[cavalry]] [[brigade]]s and its [[Military doctrine|doctrine]] emphasized cavalry units as [[elite]] units, other armies of that time (including German and Soviet) also fielded and extensively used horse cavalry units. [[Polish cavalry]] (equipped with modern small arms and light artillery like the highly effective Bofors 37 mm antitank gun) never charged German tanks or entrenched infantry or artillery directly but usually acted as [[mobile infantry]] (like [[dragoon]]s) and [[reconnaissance]] units and executed cavalry charges only in rare situations, against enemy infantry. The article about the [[Battle of Krojanty]] (when Polish cavalry were fired on by hidden |

*''The Polish military was so backward they fought tanks with cavalry'': Although Poland had 11 [[cavalry]] [[brigade]]s and its [[Military doctrine|doctrine]] emphasized cavalry units as [[elite]] units, other armies of that time (including German and Soviet) also fielded and extensively used horse cavalry units. [[Polish cavalry]] (equipped with modern small arms and light artillery like the highly effective Bofors 37 mm antitank gun) never charged German tanks or entrenched infantry or artillery directly but usually acted as [[mobile infantry]] (like [[dragoon]]s) and [[reconnaissance]] units and executed cavalry charges only in rare situations, against enemy infantry. The article about the [[Battle of Krojanty]] (when Polish cavalry were fired on by hidden armored vehicles, rather than charging them) describes how this myth originated. |

||

*''The Polish air force was destroyed on the ground in the first days of the war'': The [[Polish Air Force]], though numerically inferior, was not destroyed on the ground because combat units had been moved from air bases to small camouflaged airfields shortly before the war. Only a number of [[trainer aircraft|trainers]] and auxiliary aircraft were destroyed on the ground on airfields. The Polish Air Force remained active in the first two weeks of the campaign, causing serious damage to the [[Luftwaffe]]. Many skilled Polish [[aviator|pilots]] escaped afterwards to the United Kingdom and were deployed by the [[Royal Air Force|RAF]] during the [[Battle of Britain]]. Fighting from British bases, Polish pilots were also, on average, the most successful in shooting down German planes <ref name="PolishPilots>[[No. 303 (Polish) Squadron RAF|No. 303 "Kościuszko" Polish Fighter Squadron]] formed from Polish pilots in the United Kingdom almost 2 months after the [[Battle of Britain]] begun is famous for achieving the highest number of enemy kills during the Battle of Britain of all fighter squadrons then in operation.</ref>. |

*''The Polish air force was destroyed on the ground in the first days of the war'': The [[Polish Air Force]], though numerically inferior, was not destroyed on the ground because combat units had been moved from air bases to small camouflaged airfields shortly before the war. Only a number of [[trainer aircraft|trainers]] and auxiliary aircraft were destroyed on the ground on airfields. The Polish Air Force remained active in the first two weeks of the campaign, causing serious damage to the [[Luftwaffe]]. Many skilled Polish [[aviator|pilots]] escaped afterwards to the United Kingdom and were deployed by the [[Royal Air Force|RAF]] during the [[Battle of Britain]]. Fighting from British bases, Polish pilots were also, on average, the most successful in shooting down German planes <ref name="PolishPilots>[[No. 303 (Polish) Squadron RAF|No. 303 "Kościuszko" Polish Fighter Squadron]] formed from Polish pilots in the United Kingdom almost 2 months after the [[Battle of Britain]] begun is famous for achieving the highest number of enemy kills during the Battle of Britain of all fighter squadrons then in operation.</ref>. |

||

*''Poland offered little resistance and surrendered quickly'': Germany sustained relatively heavy losses, especially in vehicles and planes: Poland cost Germans approximately the equipment of an entire armored division and 40% of its air strength.[http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0060009772&id=vgeMFaiwdqIC&pg=PA75&lpg=PA75&dq=1939+Polish+submarines&sig=Xl1CkFcNxhfo2ARy9zTtUuEyA7A] As for duration, it should be noted that the September Campaign lasted only about one week less than the [[Battle of France]] in 1940, even though the Anglo-French allied forces were much closer to parity with the Germans in numerical strength and equipment<ref name="FrenchForces>Polish to Germany forces in the September Campaign: 1,000,000 soldiers 4,300 guns, 880 tanks, 435 aircraft (Poland) to 1,800,000 soldiers, 10,000 guns, 2,800 tanks, 3,000 aircraft (Germany). French and participating Allies to German forces in the Battle of France: 2,862,000 soldiers, 13,974 guns, 3,384 tanks, 3,099 aircraft 2 (Allies) to 3,350,000 soldiers, 7,378 guns, 2,445 tanks, 5,446 aircraft (Germany).</ref>. Poland also never officially surrendered to the Germans. |

*''Poland offered little resistance and surrendered quickly'': Germany sustained relatively heavy losses, especially in vehicles and planes: Poland cost Germans approximately the equipment of an entire armored division and 40% of its air strength.[http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0060009772&id=vgeMFaiwdqIC&pg=PA75&lpg=PA75&dq=1939+Polish+submarines&sig=Xl1CkFcNxhfo2ARy9zTtUuEyA7A] As for duration, it should be noted that the September Campaign lasted only about one week less than the [[Battle of France]] in 1940, even though the Anglo-French allied forces were much closer to parity with the Germans in numerical strength and equipment<ref name="FrenchForces>Polish to Germany forces in the September Campaign: 1,000,000 soldiers 4,300 guns, 880 tanks, 435 aircraft (Poland) to 1,800,000 soldiers, 10,000 guns, 2,800 tanks, 3,000 aircraft (Germany). French and participating Allies to German forces in the Battle of France: 2,862,000 soldiers, 13,974 guns, 3,384 tanks, 3,099 aircraft 2 (Allies) to 3,350,000 soldiers, 7,378 guns, 2,445 tanks, 5,446 aircraft (Germany).</ref>. Poland also never officially surrendered to the Germans. |

||

Revision as of 01:55, 3 March 2007

| Invasion of Poland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

| German soldiers destroying Polish border checkpoint on 1 September. World War II begins. German troops dismantle a Polish border checkpoint, September 1, 1939, as World War II begins. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

(Army Group North), (Field Army Bernolak) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

39 divisions, 16 brigades, 4,300 guns, 880 tanks, 400 aircraft, Total: 950,000[1] |

Germany: 56 divisions, 4 brigades, 10,000 guns, 2,700 tanks, 1,300 aircraft, Soviet Union: 33+ divisions, 11+ brigades, Slovakia: 3 divisions, Total: 1,800,000 Germans, 800,000+ Soviets, 50,000 Slovaks, Grand total: 2,650,000+[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

66,000 dead,[2] 133,700 wounded, 694,000 captured |

Germany: 16,343 dead,[2] 27,280 wounded, 320 missing, Soviet Union: 1,475 dead or missing, 2,383 wounded | ||||||

The Invasion of Poland in 1939 (also known in Poland as the 1939 Defensive War (Wojna obronna 1939 roku), in Germany as the Poland Campaign (Polenfeldzug), codenamed Fall Weiss ("Case White") by the German General Staff, and sometimes called the Polish September Campaign or the Polish-German War of 1939), which precipitated the onset of World War II, was carried out by Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and a small German-allied Slovak contingent. The invasion of Poland marked the start of World War II in Europe as Poland's western allies, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand[3], declared war on Germany on September 3, followed quickly by France, South Africa and Canada, among others. The campaign began on September 1 1939, one week after the signing of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and ended on October 6 1939, with Germany and the Soviet Union occupying the entirety of Poland.

Following a German-staged "Polish attack" on 31 August 1939, on the first of September, German forces invaded Poland from the north, south, and west. Spread thin defending their long borders, the Polish armies were soon forced to withdraw east. After the mid-September Polish defeat in the Battle of the Bzura, the Germans gained an undisputed advantage. Polish forces then began a withdrawal southeast, following a plan that called for a long defence in the Romanian bridgehead area where the Polish forces were to await an expected Allied counter-attack and relief[4].

On September 17 1939, the Soviet Red Army invaded the eastern regions of Poland in cooperation with Germany. The Soviets were carrying out their part of the secret appendix of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which divided Eastern Europe into Nazi and Soviet spheres of influence. Facing the second front, the Polish government decided the defence of the Romanian bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered the evacuation of all troops to neutral Romania. By 1 October, Germany and the Soviet Union had completely overrun Poland, although the Polish government never surrendered. In addition, Poland's remaining land and air forces were evacuated to neighboring Romania and Hungary. Many of the exiles subsequently joined the recreated Polish Army in allied France, French-mandated Syria and the United Kingdom.

In the aftermath of the September Campaign, a resistance movement was formed. Poland's fighting forces continued to contribute to Allied military operations, and did so throughout the duration of World War II. Germany captured the Soviet-occupied areas of Poland when it invaded the Soviet Union on June 22 1941 and lost the territory in 1944 to an advancing Red Army. Over the course of the war, Poland lost over 20% of its pre-war population under an occupation that marked the end of the Second Polish Republic.

Opposing forces

Germany

Germany had a significant numerical advantage over the Polish, and had developed a significant military prior to the conflict. The Heer (Army) had some 2,400 tanks organized into six panzer divisions, utilizing a new operational doctrine. It held that these divisions should act in coordination with other elements of the military, punching holes in the enemy line and isolating selected enemy units which would be encircled and destroyed. This would be repeated and followed up by less mobile mechanized infantry and foot soldiers. The Luftwaffe (Air Force) provided both tactical and strategic air power, particularly dive bombers that attacked and disrupted the enemy's supply and communications lines. Together the new operational methods were nicknamed blitzkrieg (lightning war), but historians generally hold that German operations during the campaign were conservative, owing more to traditional methods. The strategy of the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces) was more in line with Vernichtungsgedanken, or a focus on envelopment to create pockets in broad-front annihilation.

Aircraft played a major role in the campaign. Bomber aircraft also attacked cities, causing huge losses amongst the civilian population through terror bombing. The Luftwaffe forces consisted of 1,180 fighter aircraft: 290 Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers, 290 conventional bombers (mainly of the He 111 type), and an assortment of 240 naval aircraft. In total, Germany had close to 3,000 aircraft, with nearly two thirds of them up to modern standards. Half of these were deployed on the Polish front. The Luftwaffe was among the best trained and equipped air forces in 1939.

Poland

Between 1936 and 1939, Poland invested heavily in industrialization in the Central Industrial Region (Centralny Okręg Przemysłowy). Preparations for a defensive war with Germany were ongoing for many years, but most plans assumed fighting would not begin before 1942. To raise funds for industrial development, Poland was selling much of the modern equipment it produced. The Polish Army had about a million soldiers but less than half were mobilised by 1 September. Latecomers sustained significant casualties when public transport became targets of the Luftwaffe. The Polish military had fewer armoured forces than the Germans, and these units, being dispersed within the infantry, were unable to effectively engage the enemy.

Experiences in the Polish-Soviet War shaped Polish Army organisational and operational doctrine. Unlike the trench warfare of the First World War, the Polish-Soviet War was a conflict in which the cavalry's mobility played a decisive role. Poland acknowledged the benefits of mobility but was unwilling to invest heavily in many of the expensive and unproven new inventions since then and make these additions to its armed forces. In spite of this, Polish Cavalry brigades were used as a mobile mounted infantry and had some successes against both German infantry and German cavalry.

The Polish Air Force was at a severe disadvantage against the German Luftwaffe although, contrary to popular belief, it was not destroyed on the ground. Although the Polish Air Force lacked modern fighter aircraft, its pilots were also among the world's best-trained, a fact that was proven a year later in the Battle of Britain, in which the Poles played a major part in beating the Luftwaffe.[5]

Overall, the Germans enjoyed numerical and qualitative aircraft superiority. Poland had only about 600 modern aircraft. The Polish Airforce (Lotnictwo Wojskowe) had about 185 PZL P.11 and some 95 PZL P.7 fighters, 175 PZL.23 Karaś B, 35 Karaś A and by September over 100 PZL.37 Łoś were produced. Additionally there were over a thousand obsolete transport, reconnaissance and training aircraft. However for the September Campaign only some 70% those aircraft were mobilised. Only 36 PZL.37 Łoś bomber aircraft were deployed for action. Interestingly all those aircraft were of indigenous Polish design, bombers being more modern than fighters according to the Ludomil Rayski airforce expansion plan relying on the strong bomber force. Polish fighter aircraft were a generation older than their German counterparts. The Polish PZL P.11 fighter, produced in the early 1930s, was capable of only 365 km/h (about 220 mi/hr), far less than German bombers, to compensate the pilots relied on the P-11 maneuvrability and high diving speed.

The Polish Navy was a small fleet comprising destroyers, submarines and smaller support vessels. Most Polish surface units followed Operation Peking, leaving Polish ports on August 20 and escaping to the North Sea to join with the British Royal Navy. Submarine forces participated in Operation Worek, with the goal of engaging and damaging German shipping in the Baltic Sea, but with much less success. In addition, many Polish Merchant Marine ships joined the British merchant fleet and took part in wartime convoys.

The tank force consited of two armoured brigades, four independent tank batalions and some 30 companies of TKS tankettes attached to infantry divisions and cavalry brigades.

Soviet Union

Order of battle

Order of battle of Poland:

- Polish army order of battle in 1939

- Polish Air Force order of battle in 1939

- Polish Navy order of battle in 1939

- Polish armaments 1939-1945

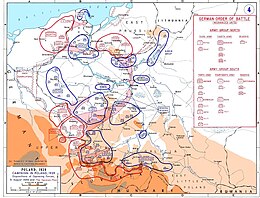

Order of battle of invading forces:

- German order of battle for Operation Fall Weiss

- Soviet order of battle for invasion of Poland in 1939

Prelude to the campaign

The Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, took power in Germany in 1933. At first, Hitler pursued a policy of rapprochement with Poland, culminating in the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934. Early foreign policy worked to maneuver Poland into the Anti-Comintern Pact, forming a cooperative front against the Soviet Union. Germany sought to grab hold of Soviet territory, acquire Lebensraum and expand Großdeutschland.[2] Poland would be granted territory of its own, to its northeast, but the concessions the Poles were expected to make meant that their homeland would become largely dependant on Germany, functioning as little more than a client state. Some felt Polish independence would eventually be threatened altogether.[3]

In addition to Soviet territory, the Nazis were also interested in establishing a new border with Poland because the German exclave of East Prussia was separated from the rest of the Reich by the "Polish Corridor." Many Germans also wanted to incorporate the Free City of Danzig into Germany. While Danzig had a predominantly German population, the Corridor constituted land long disputed between Poland and Germany. After the Treaty of Versailles, Poland acquired the Corridor and this led to shifts in the region's population. Hitler sought to reverse this trend and made an appeal to German nationalism, promising to "liberate" the Germans still in the Corridor, as well as Danzig, as the port city was now under the control of the League of Nations.

In 1938, Germany began to increase its demands for Danzig while proposing that a roadway be built in order to connect East Prussia with Germany proper, running through the Polish Corridor.[4] Poland rejected this proposal, fearing that after accepting these demands, it would become increasingly subject to the will of Germany and eventually lose independence as the Czechs had.[5] The Poles also distrusted Hitler and his intentions.[6] At the same time, Germany's collaboration with anti-Polish Ukrainian nationalists from the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists further weakened German credibility in Polish eyes, as it was seen as an effort to isolate and weaken Poland. The British were also aware of this. On March 30, Poland was backed by a guarantee from Britain and France, though neither country was willing to pledge military support in Poland's defense. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, still hoped to strike a deal with Hitler regarding the Free City of Danzig (and possibly the Polish Corridor) and Hitler hoped for the same. By again resorting to appeasement, Chamberlain and his supporters believed war could be avoided and hoped Germany would agree to leave the rest of Poland alone. German hegemony over Central Europe was also at stake.

With tensions mounting, Germany turned to aggressive diplomacy, unilaterally withdrawing from both the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934 and the London Naval Agreement of 1935 on April 28, 1939. In early 1939, Hitler had already issued orders to prepare for a possible "solution of the Polish problem by military means." Another crucial step towards war was the surprise signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August, the denouement of secret Nazi-Soviet talks held in Moscow which capitalized on France and Britain's own failure to secure an alliance with the Soviet Union. As a result, Germany neutralized the possibility of Soviet opposition in a potential campaign against Poland. In a secret protocol of this pact, the Germans and the Soviets agreed to divide Eastern Europe, including Poland, into two spheres of influence; the western third of the country was to go to Germany and the eastern two-thirds to the Soviet Union. Although Western Allies' intelligence had uncovered the secret appendix concerning Poland, this information was not shared with the Polish government.

The German assault was originally scheduled to begin at 0400 on 26 August. However, on August 25, the Polish-British Common Defence Pact was signed as an annex to the Franco-Polish Military Alliance. In this accord, Britain had committed itself to the defence of Poland, guaranteeing to preserve Polish independence. At the same time, the British and the Poles were hinting to Berlin that they were willing to resume discussions - not at all how Hitler hoped to frame the conflict. Thus, he wavered and postponed his attack until 1 September, managing to halt the entire invasion "in mid-leap", with the exception of a few units that were outside communication lines, towards the south (the Nazi press announced that fanatical Slovakians were behind the cross border raid).

On the 26 August, Hitler tried to dissuade the British and the French from interfering in the conflict, even pledging that the Wehrmacht forces would be made available to Britain's Empire in the future.[6] In any case, the negotiations convinced Hitler that there was little chance the Western Allies would declare war on Germany, and even if they did, due to the lack of territorial guarantees to Poland, they would be willing to negotiate a compromise favourable to Germany after its conquest of Poland. Meanwhile, the number of increased overflights by high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft and cross border troop movements (sappers to Danzig) signalled that war was imminent.

On 29 August, prompted by the British, Germany issued one last diplomatic offer, with Case White yet to be rescheduled. At midnight on August 29, German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop handed British Ambassador Sir Neville Henderson the list of terms which would allegedly ensure peace in regards to Poland. Danzig was to return to Germany (Gdynia would remain with Poland) and there was to be a plebiscite in the Polish Corridor, based on residency in 1919, within the year.[7] An exchange of minority populations between the two countries was proposed.[8] A Polish plenipotentiary, with full powers, was to arrive in Berlin and accept these terms by noon the next day.[9] The British Cabinet viewed the terms as "reasonable," except the demand for the urgent plenipotentiary, a form of ultimatum.[10] When Polish Ambassador Lipski went to see Ribbentrop on August 30, he announced that he did not have the full power to sign and Ribbentrop dismissed him. It was then broadcasted that Poland had rejected Germany's offer and negotiations with Poland came to an end.[11]

On 30 August, the Polish Navy sent its destroyer flotilla to Britain executing Operation Peking. On the same day, Marshal of Poland Edward Rydz-Śmigły announced mobilization of Polish troops. However, he was pressured into revoking the order by the French, who apparently still hoped for a diplomatic settlement, failing to realize that the Germans were fully mobilized and concentrated at the Polish border. During the night of August 31 the Gleiwitz incident ("Polish" attack on the radio station) was staged near the German border city of Gleiwitz, in Upper Silesia. On 31 August, 1939, Hitler ordered hostilities against Poland to start at 4:45 the next morning. Due to the prior discontinuation, Poland managed to mobilise only 70% of its planned forces, and many units were still forming or moving to their designated frontline positions.

Details of the campaign

Plans

German plan

The German plan Fall Weiss, for what became known as the September campaign, was created by General Franz Halder, chief of the general staff, and directed by General Walther von Brauchitsch, the commander in chief of the upcoming campaign. The plan called for the start of hostilities before the declaration of war, which pursued a traditional doctrine of mass encirclement and the destruction of enemy forces. Germany's material advantages, including the use of modern airpower and tanks, were to be of great advantage. The infantry - far from completely mechanized but fitted with fast moving artillery and logistic support - was to be supported by German tanks (panzers) and small numbers of truck-mounted infantry (the Schützen regiments, forerunners of the panzergrenadiers) to assist the rapid movement of troops and concentrate on localized parts of the enemy front, eventually isolating segments of the enemy, surrounding, and destroying them. The pre-war armored idea (which an American journalist in 1939 would dub Blitzkrieg), which was advocated by some generals including Guderian, would have had the armor blasting holes in the enemy's front and ranging deep into the enemy's rear areas, but in actuality, the campaign in Poland would be fought along more traditional lines. This was due to conservatism on the part of the German high command, who mainly restricted the role of armor and mechanized forces to supporting the conventional infantry divisions.

Poland was a country well suited for mobile operations when the weather cooperated - a country of flat plains with long frontiers totalling almost 3,500 miles, Poland had long borders with Germany on the west and north (facing East Prussia) of 1,250 miles. Those had been extended by another 500 miles on the southern side in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement of 1938; the German incorporation of Bohemia and Moravia and creation of the German puppet state of Slovakia meant that Poland's southern flank was exposed to invasion.

German planners intended to fully utilise their advantageously long border with the great enveloping manoeuvre of Fall Weiss. German units were to invade Poland from three directions:

- A main attack from the German mainland through the western Polish border. This was to be carried out by Army Group South commanded by General Gerd von Rundstedt, attacking from German Silesia and from the Moravian and Slovak border: General Johannes Blaskowitz's 8th Army was to drive eastward against Łódź; General Wilhelm List's 14th Army was to push on toward Kraków and to turn the Poles' Carpathian flank; and General Walter von Reichenau's 10th Army, in the centre with Army Group South's armour, was to deliver the decisive blow with a northwestward thrust into the heart of Poland.

- A second route of attack from the northern Prussian area. General Fedor von Bock commanded Army Group North comprising General Georg von Küchler's 3rd Army, which struck southward from East Prussia, and General Günther von Kluge's 4th Army, which struck eastward across the base of the Polish Corridor.

- A tertiary attack by part of Army Group South's allied Slovak units from the territory of Slovakia.

- From within Poland the German minority would assist in the assault on Poland by engaging in diversion and sabotage operations through Selbstschutz units prepared before the war.

All three assaults were to converge on Warsaw, while the main Polish army was to be encircled and destroyed west of the Vistula. Fall Weiss was initiated on 1 September 1939 and was the first operation of the Second World War in Europe.

Polish plan

The Polish defense plan, Zachód (West), was shaped by political determination to deploy forces directly at the German-Polish border, based upon London's promise to come to Warsaw's military aid in the event of invasion. Moreover, with the nation's most valuable natural resources, industry and highly populated regions near the western border (Silesia region), Polish policy centered on the protection of such regions, especially as many politicians feared that if Poland should retreat from the regions disputed by Germany (like the Polish Corridor, cause of the famous "Danzig or War" ultimatum), Britain and France would sign a separate peace treaty with Germany similar to the Munich Agreement of 1938. In addition, none of those countries specifically guaranteed Polish borders or territorial integrity. On those grounds, Poland disregarded French advice to deploy the bulk of their forces behind the natural barriers of the wide Vistula and San rivers, even though some Polish generals supported it as a better strategy. The Zachód plan did allow the Polish armies to retreat inside the country, but it was supposed to be a slow retreat behind prepared positions near rivers (Narew, Vistula and San), giving the country time to finish its mobilisation, and was to be turned into a general counteroffensive when the Western Allies would launch their own promised offensive.

The Polish Army's most pessimistic fall-back plan involved retreat behind the river San to the southeastern voivodships and their lengthy defence (the Romanian bridgehead plan). The British and French estimated that Poland should be able to defend that region for two to three months, while Poland estimated it could hold it for at least six months. This Polish plan was based around the expectation that the Western Allies would keep their end of the signed alliance treaty and quickly start an offensive of their own. However, neither the French nor the British government made plans to attack Germany while the Polish campaign was fought. In addition, they expected the war to develop into trench warfare much like World War I had, forcing the Germans to sign a peace treaty restoring Poland's borders. The Polish government, however, was not notified of this strategy and based all of its defence plans on the expectation of a quick relief action by their Western Allies.

The plan to defend the borders contributed vastly to the Polish defeat. Polish forces were stretched thin on the very long border and, lacking compact defence lines and good defence positions along unadvantegeous terrain, mechanized German forces often were able to encircle them. In addition, supply lines, were often poorly protected. Approximately one-third of Poland's forces were concentrated in or near the Polish Corridor (in northwestern Poland), where they were perilously exposed to a double envelopment — from East Prussia and the west combined and isolated in a pocket. In the south, facing the main avenues of a German advance, the Polish forces were thinly spread. At the same time, nearly another one-third of Poland's troops were massed in reserve in the north-central part of the country, between the major cities of Łódź and Warsaw, under commander in chief Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły. The Poles' forward concentration in general forfeited their chance of fighting a series of delaying actions, since their army, unlike some of Germany's, traveled largely on foot and was unable to retreat to their defensive positions in the rear or to staff them before they were overrun by German mechanized columns.

The political decision to defend the border was not the Polish high command's only strategic mistake. Polish pre-war propaganda stated that any German invasion would be easily repelled, so that the eventual Polish defeats in the September Campaign came as a shock to many civilians, who, unprepared for such news and with no training for such an event, panicked and retreated east, spreading chaos, lowering troop morale and making road transportation for Polish troops very difficult. The propaganda also had some negative consequences for the Polish troops themselves, whose communications, disrupted by German mobile units operating in the rear and civilians blocking roads, were further thrown into chaos by bizarre reports from Polish radio stations and newspapers, which often reported imaginary victories and other military operations. This led to some Polish troops being encircled or taking a stand against overwhelming odds, when they thought they were actually counterattacking or would soon receive reinforcements from other victorious areas[12].

Phase 1: German invasion

Following a number of German-staged incidents (Operation Himmler), which gave German propaganda an excuse to claim that German forces were acting in self-defense, the first regular act of war took place on September 1 1939, at 04:40 hours, when the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) attacked the Polish town of Wieluń, destroying 75% of the city and killing close to 1,200 people, most of them civilians. Five minutes later, at 04:45 hours, the old German battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Polish military transit depot at Westerplatte, in the Free City of Danzig on the Baltic Sea. At 08:00 hours, German troops, still without a formal declaration of war issued, attacked near the Polish town of Mokra; the battle of the border had begun. Later that day, the Germans opened fronts along Poland's western, southern and northern borders, while German aircraft began raids on Polish cities. Main routes of attack led eastwards from Germany proper through the western Polish border. A second route carried supporting attacks from East Prussia in the north, and a co-operative German-Slovak tertiary attack by units (Army "Bernolak") from the territory of German-allied Slovakia in the south. All three assaults converged on the Polish capital of Warsaw.

The Allied governments declared war on Germany on September 3; however, they failed to provide Poland with any meaningful support. The German-French border had a few minor skirmishes, although the majority of German forces, including eighty-five percent of their armoured forces, were engaged in Poland. Despite some Polish successes in minor border battles, German technical, operational and numerical superiority forced the Polish armies to withdraw from the borders towards Warsaw and Lwów. The Luftwaffe gained air superiority early in the campaign. By 3 September, when Kluge in the north had reached the Vistula (some 10 kilometres from the German border at that time) river and Küchler was approaching the Narew River, Reichenau's armour was already beyond the Warta river; two days later his left wing was well to the rear of Łódź and his right wing at the town of Kielce; and by 8 September one of his armoured corps was on the outskirts of Warsaw, having advanced 140 miles in the first week of war. Light divisions on Reichenau's right were on the Vistula between Warsaw and the town of Sandomierz by 9 September, while List, in the south, was on the river San above and below the town of Przemyśl. At the same time, Guderian led his 3rd Army tanks across the Narew, attacking the line of the Bug River already encircling Warsaw. All the German armies had made progress in fulfilling their parts of the Fall Weiss plan. The Polish armies were splitting up into uncoordinated fragments, some of which were retreating while others were delivering disjointed attacks on the nearest German columns.

Polish forces abandoned regions of Pomerania, Greater Poland and Silesia in the first week of the campaign, after a series of battles known as the Battle of the Border. Thus the Polish plan for border defence was proven a dismal failure. The German advance, as a whole, was not slowed down and the Germans moved quickly, overwhelming secondary positions. On 10 September, the Polish commander in chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły, ordered a general retreat to the southeast, towards the so-called Romanian bridgehead. Meanwhile, the Germans were tightening their encirclement of the Polish forces west of the Vistula (in the Łódź area and, still farther west, around Poznań) and also penetrating deeply into eastern Poland. Warsaw, under heavy aerial bombardment since the first hours of the war, was attacked on 9 September and was put under siege on September 13. Around that time, advanced German forces had also reached the city of Lwów, a major metropolis of eastern Poland. 1150 German aircraft bombed Warsaw on September 24.

The largest battle during this campaign, the Battle of Bzura, took place near the Bzura river west of Warsaw and lasted from 9 September to 18 September. Polish armies Poznań and Pomorze, retreating from the border area of the Polish Corridor, attacked the flank of the advancing German 8th army, but the counterattack failed after initial success. After the defeat, Poland lost its ability to take the initiative and counterattack on a large scale.

The Polish government (of president Ignacy Mościcki) and the high command (of Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły) left Warsaw in the first days of the campaign and headed southeast, arriving in Brześć on 6 September. General Rydz-Śmigły ordered the Polish forces to retreat in the same direction, behind the Vistula and San rivers, beginning the preparations for the long defence of the Romanian bridgehead area.

Phase 2: Soviet aggression

From the beginning of the Polish campaign the German government repeatedly asked Stalin and Molotov to act upon the August agreement and attack Poland from the east.[13] Worried by an unexpectedly rapid German advance and eager to grab their allotted share of the country, Soviet forces attacked Poland on September 17. It was agreed that the USSR would relinquish its interest in the territories between the new border and Warsaw in exchange for inclusion of Lithuania in the Soviet "zone of interest." The USSR had openly supported German aggression and Molotov stated after the Polish defeat: Germany, which has lately united 80 million Germans, has submitted certain neighboring countries to her supremacy and gained military strength in many aspects, and thus has become, as clearly can be seen, a dangerous rival to principal imperialistic powers in Europe - England and France. That is why they declared war on Germany on a pretext of fulfilling the obligations given to Poland. It is now clearer than ever, how remote the real aims of the cabinets in these countries were from the interests of defending the now disintegrated Poland or Czechoslovakia[14]

By 17 September 1939 the Polish defense was already broken and their only hope was to retreat and reorganize along the Romanian Bridgehead. However, these plans were rendered obsolete nearly overnight, when the over 800,000 strong Soviet Union Red Army attacked and created the Belarussian and Ukrainian fronts after invading the eastern regions of Poland. This was in violation of the Riga Peace Treaty, the Soviet-Polish Non-Aggression Pact and other international treaties, both bilateral and multilateral[15]. Soviet diplomacy claimed that they were "protecting the Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities of eastern Poland in view of Polish imminent collapse." In fact Soviets were acting in co-operation with the Nazis, carving Europe into Nazi and Soviet spheres of influence as specified in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.[13]

Polish border defence forces in the east, known as the Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza, consisted of about 25 battalions. Edward Rydz-Śmigły ordered them to fall back and not engage the Soviets. This, however, did not prevent some clashes and small battles, like the Battle of Grodno, as soldiers and local population attempted to defend the city. The Soviets murdered a number of Poles, including prisoners-of-war like General Józef Olszyna-Wilczyński. Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists rose against the Poles, and communist partisans organised local revolts, e.g. in Skidel, robbing and murdering Poles. Those movements were quickly disciplined by the NKVD. The Soviet invasion was one of the decisive factors that convinced the Polish government that the war in Poland was lost. Prior to the Soviet attack from the East, the Polish military's fall-back plan had called for long-term defence against Germany in the southern-eastern part of Poland, while awaiting relief from a Western Allies attack on Germany's western border. However, the Polish government refused to surrender or negotiate a peace with Germany and ordered all units to evacuate Poland and reorganize in France.

Meanwhile, Polish forces tried to move towards the Romanian bridgehead area, still actively resisting the German invasion. From 17 September to 20 September, the Polish Armies Kraków and Lublin were crippled at the Battle of Tomaszów Lubelski, the second largest battle of the campaign. The city of Lwów capitulated on 22 September in a turn of events illustrative of the bizarre turn due to Soviet intervention; the city had been attacked by the Germans over a week earlier and in the middle of the siege, the German troops handed operations over to their Soviet allies. Despite a series of intensifying German attacks, Warsaw, defended by quickly reorganised retreating units, civilian volunteers and militia, held out until its capitulation on 28 September. The Modlin Fortress north of Warsaw capitulated on 29 September after an intense 16-day battle. Some isolated Polish garrisons managed to hold their positions long after being surrounded by German forces. Westerplatte enclave's tiny garrison capitulated on 7 September, and Oksywie garrison held until 19 September; Hel was defended until 2 October. Despite a Polish victory at the battle of Szack, after which the Soviets executed all the NCOs and officers they had managed to capture, the Red Army reached the line of rivers Narew, Western Bug, Vistula and San by September 28, in many cases meeting German units advancing from the other side. Polish defenders on the Hel peninsula on the shore of the Baltic Sea held out until 2 October. The last operational unit of the Polish Army, General Franciszek Kleeberg's Samodzielna Grupa Operacyjna "Polesie", capitulated after the 4-day Battle of Kock near Lublin on 6 October, marking the end of the September Campaign.

Civilian losses

The Polish September Campaign was an instance of total war that would be repeated continuously throughout World War II. Consequently, civilian casualties were high during and after combat. From the start of the campaign, the Luftwaffe attacked civilian targets and columns of refugees along the roads to wreak havoc, disrupt communications and target Polish morale. The first such attack occurred at 4 AM on September 1 during the Bombing of Wieluń, in which nearly 1200 civilians were killed by a Luftwaffe air raid on Wieluń. Finally, apart from the victims of the battles, the German forces (both SS and the regular Wehrmacht) are credited with the mass murder of several thousands of Polish POWs and civilians. Also, during a planned Operation Tannenberg, nearly 20,000 Poles were shot in 760 mass execution sites by special units, the Einsatzgruppen, in addition to regular Wehrmacht, SS and Selbstschutz.

In a particular instance on September 3, 1939, known as "Bromberg Bloody Sunday," Polish Army units withdrawing through the city of Bromberg heard shots, supposedly from German fifth columnists believed to be firing atop churches and rooftops at soldiers and civilians. The Polish soldiers and civilians lynched many of the alleged German saboteurs. Between 223 and 358 ethnic Germans were killed in Bromberg alone and more were killed in the surrounding villages. The exact number of the victims is still subject to dispute. In reprisal, German forces executed some 3,000 Poles and by the year's end sent an additional 13,000 to the Stutthof concentration camp.

Altogether, the civilian losses of Polish population amounted to 150,000 while German civilian losses amounted to roughly 5,000.

Aftermath

At the end of the September Campaign, Poland was divided among Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, Lithuania and Slovakia. Nazi Germany annexed parts of Poland, while the rest was governed by the so-called General Government. On September 28, another secret German-Soviet protocol modified the arrangements of August: all Lithuania was to be a Soviet sphere of influence, not a German one; but the dividing line in Poland was moved in Germany's favor, to the Bug River. Even though water barriers separated most of the spheres of interest, the Soviet and German troops met each other on a number of occasions. The most remarkable event of this kind happened in Brest-Litovsk on 22 September, 1939. The German 19th panzer corps under the command of Heinz Guderian had occupied Brest-Litovsk, which lay within the Soviet sphere of interest. When the Soviet 29th Tank Brigade under the command of S. M. Krivoshein approached Brest-Litovsk, the commanders negotiated that the German troops would withdraw and the Soviet troops enter the city saluting each other.[16] Just three days earlier, however, the parties had a more damaging encounter near Lviv, when the German 137th Gebirgsjägerregimenter (mountain infantry regiment) attacked a reconnaissance detachment of the Soviet 24th Tank Brigade; after a few casualties on both sides, the parties turned to negotiations, as a result of which the German troops left the area, and the Red Army troops entered L'viv on 22 September. At Brest-Litovsk, Soviet and German commanders held a joint victory parade before German forces withdrew westward behind a new demarcation line[17].

About 65,000 Polish troops were killed in the fighting, with 420,000 others being captured by the Germans and 240,000 more by the Soviets (grand total 680,000 prisoner). Up to 120,000 Polish troops escaped to neutral Romania (through the Romanian Bridgehead) and Hungary, and another 20,000 escaped to Latvia and Lithuania, with the majority eventually making their way to France or Britain. Most of the Polish Navy succeeded in evacuating to Britain as well. German personnel losses were less than their enemies (~16,000 KIA), but the loss of approximately 30% of armored vehicles during the campaign was one of the reasons the plans for an immediate attack west were discarded. [citation needed]

Neither side—Germany, the Western Allies or the Soviet Union—expected that the German invasion of Poland would lead to the war that would surpass World War I in its scale and cost. It would be months before Hitler would see the futility of his peace negotiation attempts with Great Britain and France, but the culmination of combined European and Pacific conflicts would result in what was truly a "world war". Thus, what was not visible to most politicians and generals in 1939 is clear from the historical perspective: The Polish September Campaign marked the beginning of the Second World War in Europe, which combined with the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the Pacific War in 1941 would form the conflict known as World War II.

The invasion of Poland led to Britain and France declaring war on Germany on September 3; however, they did little to affect the outcome of the September Campaign. This lack of direct help during September 1939 led many Poles to believe that they had been betrayed by their Western allies.

On May 23 1939 Adolf Hitler explained to his officers that the object of the aggression was not Danzig, but the need to obtain German Lebensraum and details of this concept would be later formulated in the infamous Generalplan Ost. [7] [8] The blitzkrieg decimated urban residential areas, civilians soon became indistinguishable from combatants and the forthcoming German occupation (General Government, Reichsgau Wartheland) was one of the most brutal episodes of World War II, resulting in over 6 million Polish deaths (over 20% of the country's total population), including the mass murder of 3 million Poles, regardless of religious beliefs, in extermination camps like Auschwitz.[9] Red Army occupied the Polish territories with mostly Ukrainian and Belorussian population. Soviets, met at the beginning as liberators by local people, shortly after started to introduce communist ideology in the area. Badly adapted by the population, this led to a powerful anti-soviet resistance in the West Ukraine. Soviet occupation between 1939 and 1941 resulted in the death or deportation of least 1.8 million former Polish citizens, when all who were deemed dangerous to the communist regime were subject to sovietization, forced resettlement, imprisonment in labour camps (the Gulags) or simply murdered, like the Polish officers in the Katyn massacre. Part of these casualties were due to the attacks of the Ukrainian nationalists on the Polish villages in the West Ukraine, where vengeful feeling was particularly strong. Soviet atrocities commenced again after Poland was "liberated" by the Red Army in 1944, with events like the persecution of the Home Army soldiers and execution of its leaders (Trial of the Sixteen).

Myths

There are several common misconceptions regarding the Polish September Campaign:

- The Polish military was so backward they fought tanks with cavalry: Although Poland had 11 cavalry brigades and its doctrine emphasized cavalry units as elite units, other armies of that time (including German and Soviet) also fielded and extensively used horse cavalry units. Polish cavalry (equipped with modern small arms and light artillery like the highly effective Bofors 37 mm antitank gun) never charged German tanks or entrenched infantry or artillery directly but usually acted as mobile infantry (like dragoons) and reconnaissance units and executed cavalry charges only in rare situations, against enemy infantry. The article about the Battle of Krojanty (when Polish cavalry were fired on by hidden armored vehicles, rather than charging them) describes how this myth originated.

- The Polish air force was destroyed on the ground in the first days of the war: The Polish Air Force, though numerically inferior, was not destroyed on the ground because combat units had been moved from air bases to small camouflaged airfields shortly before the war. Only a number of trainers and auxiliary aircraft were destroyed on the ground on airfields. The Polish Air Force remained active in the first two weeks of the campaign, causing serious damage to the Luftwaffe. Many skilled Polish pilots escaped afterwards to the United Kingdom and were deployed by the RAF during the Battle of Britain. Fighting from British bases, Polish pilots were also, on average, the most successful in shooting down German planes [18].

- Poland offered little resistance and surrendered quickly: Germany sustained relatively heavy losses, especially in vehicles and planes: Poland cost Germans approximately the equipment of an entire armored division and 40% of its air strength.[10] As for duration, it should be noted that the September Campaign lasted only about one week less than the Battle of France in 1940, even though the Anglo-French allied forces were much closer to parity with the Germans in numerical strength and equipment[19]. Poland also never officially surrendered to the Germans.

- The German Army used astonishing new concepts of warfare and used new technology daringly: The myth of Blitzkrieg has been dispelled by some authors, notably Matthew Cooper. Cooper writes (in The German Army 1939–1945: Its Political and Military Failure): "Throughout the Polish Campaign, the employment of the mechanised units revealed the idea that they were intended solely to ease the advance and to support the activities of the infantry…. Thus, any strategic exploitation of the armoured idea was still-born. The paralysis of command and the breakdown of morale were not made the ultimate aim of the … German ground and air forces, and were only incidental by-products of the traditional manoeuvers of rapid encirclement and of the supporting activities of the flying artillery of the Luftwaffe, both of which had as their purpose the physical destruction of the enemy troops. Such was the Vernichtungsgedanke of the Polish campaign." Vernichtungsgedanke was a strategy dating back to Frederick the Great, and was applied in the Polish Campaign little changed from the French campaigns in 1870 or 1914. The use of tanks "left much to be desired...Fear of enemy action against the flanks of the advance, fear which was to prove so disastrous to German prospects in the west in 1940 and in the Soviet Union in 1941, was present from the beginning of the war." Many early postwar histories, such as Barrie Pitt's in The Second World War (BPC Publishing 1966), incorrectly attribute German victory to "enormous development in military technique which occurred between 1918 and 1940", incorrectly citing that "Germany, who translated (British inter-war) theories into action… called the result Blitzkrieg." John Ellis, writing in Brute Force (Viking Penguin, 1990) asserted that "…there is considerable justice in Matthew Cooper's assertion that the panzer divisions were not given the kind of strategic (emphasis in original) mission that was to characterise authentic armoured blitzkrieg, and were almost always closely subordinated to the various mass infantry armies." Zaloga and Madej, in The Polish Campaign 1939 (Hippocrene Books, 1985), also address the subject of mythical interpretations of Blitzkrieg and the importance of other arms in the campaign. "Whilst Western accounts of the September campaign have stressed the shock value of the panzers and Stuka attacks, they have tended to underestimate the punishing effect of German artillery (emphasis added) on Polish units. Mobile and available in significant quantity, artillery shattered as many units as any other branch of the Wehrmacht."

See also

- Armenian quote

- History of Poland (1939–1945)

- Oder-Neisse line

- Polish cavalry brigade order of battle

- Polish contribution to World War II

- Timeline of the Polish September Campaign

- Western betrayal

- Blitzkrieg

- Vernichtungsgedanke

- War crimes of the Wehrmacht

- Treatment of the Polish citizens by the occupiers

Notes and references

- In-line:

- ^ a b Various sources contradict each other so the figures quoted above should only be taken as a rough indication of the strength estimate. The most common range differences and their brackets are: German personnel 1,500,000–1,800,000. This can be explained by inclusion (or lack of it) of Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine forces alongside Heer personnel. Luftwaffe: 1,300–3,000 planes, this can be explained by inclusion of all Luftwaffe planes (including transport, communications, training and anything not stationed at Polish front) on the larger end. Similarly Polish Air Force is given at 400–800; as with total Luftwaffe, the 800 number includes virtually 'anything that can fly'. Polish tanks: 100–880, 100 is the number of modern tanks, 880 number includes older IWWs tanks and tankettes. For all numbers, primary source is Encyklopedia PWN, article on 'KAMPANIA WRZEŚNIOWA 1939'

- ^ a b Various sources contradict each other so the figures quoted above should only be taken as a rough indication of losses. The most common range brackets for casualties are: Polish casualties—63,000 to 66,300 KIA, 134,000 WIA; German KIA—8,082 to 16,343, with MIA from 320 to 5,029, total KIA and WIA given at 45,000. The discrepancy in German casualties can be attributed to the fact that some German statistics still listed soldiers as missing decades after the war. Today the most common and accepted number for German KIA casualties is 16,343. Soviet official losses are estimated at 737-1,475 killed or missing, and 1,859-2,383 wounded. The often cited figure of 420,000 Polish prisoners of war represents only those captured by the Germans, as Soviets captured about 250,000 Polish POWs themselves, making the total number of Polish POWs about 660,000–690,000. Equipment losses are given as 236 German tanks and approximately 1,000 other vehicles to 132 Polish tanks and 300 other vehicles, 107–141 German planes to 327 Polish planes (118 fighters) (Polish PWN Encyclopedia gives number of 700 planes lost), 1 German small minelayer to 1 Polish destroyer (ORP Wicher), 1 minelayer (ORP Gryf) and several support craft. Soviets lost approximately 42 tanks in combat while hundreds more suffered technical failures.

- ^ Template:En icon History Group of the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, Wellington, New Zealand (2005). "Overview - New Zealand and the Second World War". New Zealand's History online. Ministry for Culture and Heritage, Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baliszewski Dariusz Most honoru, Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1138 (19 September 2004)]

- ^ Michael Alfred Peszke, Polish Underground Army, the Western Allies, and the Failure of Strategic Unity in World War II, McFarland & Company, 2004, ISBN 0-7864-2009-X, Google Print, p.2

- ^ http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/psf/box31/t295s04.html see also the original [1]

- ^ Documents Concerning the Last Phase of the German-Polish Crisis, Proposal for a settlement of the Danzig and the Polish Corridor Problem as well as of the question concerning the German and Polish Minorities (New York: German Library of Information), p 33-35...see also: Documents Concerning German-Polish Relations and the Outbreak of Hostilities Between Great Britain and Germany on September 3, 1939 (Miscellaneous No. 9) Message which was communicated to H.M. Ambassador in Berlin by the State Secretary on August 31, 1939 at 9:15 p.m. (London: His Majesty's (HM) Stationary Office) p. 149-153.

- ^ see: Documents Concerning German-Polish Relations, 149-153.

- ^ see: Documents Concerning German-Polish Relations, 149-153.

- ^ Final Report By the Right Honourable Sir Nevile Henderson (G.C.M.G) on the circumstances leading to the termination of his mission to Berlin September 20, 1939. (London: His Majesty's Stationary Office), p. 24

- ^ see: Final Report By the Right Honourable Sir Nevile Henderson, p. 16-18

- ^ Dariusz Baliszewski, Wojna sukcesów, Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1141 (10 October 2004)

- ^ a b Telegram: The German Ambassador in the Soviet Union, (Schulenburg) to the German Foreign Office. Moscow, September 10, 1939-9:40 p. m. and Telegram 2: he German Ambassador in the Soviet Union (Schulenburg) to the German Foreign Office. Moscow, September 16, 1939. Source: The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Last accessed on 14 November 2006

- ^ Molotov's report on March 29, 1940 http://www.histdoc.net/history/molotov.html

- ^ Apart from the two pacts mentioned, the treaties violated by the Soviet Union were: the 1919 Covenant of the League of Nations (to which the USSR adhered in 1934), the Briand-Kellog Pact of 1928 and the 1933 London Convention on the Definition of Aggression; see for instance: Template:En icon Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide... McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Кривошеин С.М. Междубурье. Воспоминания. Воронеж, 1964. (Krivoshein S. M. Between the Storms. Memoirs. Voronezh, 1964. in Russian); Guderian H. Erinnerungen eines Soldaten Heidelberg, 1951 (in German — Memoirs of a Soldier in English)

- ^ Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999-2000.

- ^ No. 303 "Kościuszko" Polish Fighter Squadron formed from Polish pilots in the United Kingdom almost 2 months after the Battle of Britain begun is famous for achieving the highest number of enemy kills during the Battle of Britain of all fighter squadrons then in operation.

- ^ Polish to Germany forces in the September Campaign: 1,000,000 soldiers 4,300 guns, 880 tanks, 435 aircraft (Poland) to 1,800,000 soldiers, 10,000 guns, 2,800 tanks, 3,000 aircraft (Germany). French and participating Allies to German forces in the Battle of France: 2,862,000 soldiers, 13,974 guns, 3,384 tanks, 3,099 aircraft 2 (Allies) to 3,350,000 soldiers, 7,378 guns, 2,445 tanks, 5,446 aircraft (Germany).

- General:

- Cooper, Matthew The German Army 1939-1945: Its Political and Military Failure. Stein and Day, Briarcliff Manor, NY, 19781 (ISBN 0-8128-2468-7)

- Baliszewski Dariusz, Wojna sukcesów, Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1141 (10 October 2004), Polish, retrieved on 24 March 2005

- Dariusz Baliszewski Most honoru, Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1138 (19 September 2004)], Polish, retrieved on 24 March 2005

- Chodakiewicz, Marek Jan. Between Nazis and Soviets: Occupation Politics in Poland, 1939-1947. Lexington Books, 2004 (ISBN 0-7391-0484-5).

- Ellis, John. Brute Force: Allied Strategy and Tactics in the Second World War. Viking Adult, 1st American ed edition, 1999. (ISBN 0-670-80773-7)

- Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999-2000, last accessed on 10 December, 2005

- Gross, Jan T. Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002 (ISBN 0-691-09603-1).

- Kennedy, Robert M. The German Campaign in Poland (1939). Zenger Pub Co, 1980 (ISBN 0-89201-064-9).

- Lukas, Richard C. Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles Under German Occupation, 1939-1944. Hippocrene Books, Inc, 2001 (ISBN 0-7818-0901-0).

- Majer, Diemut et al. Non-Germans under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe, with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939-1945. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003 (ISBN 0-8018-6493-3)

- Prazmowska, Anita J. Britain and Poland 1939-1943 : The Betrayed Ally. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995 (ISBN 0-521-48385-9).

- Rossino, Alexander B. Hitler Strikes Poland: Blitzkrieg, Ideology and Atrocity. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003 (ISBN 0-7006-1234-3).

- Smith, Peter C. Stuka Spearhead: The Lightning War from Poland to Dunkirk 1939-1940. Greenhill Books, 1998 (ISBN 1-85367-329-3).

- Sword, Keith The Soviet Takeover of the Polish Eastern Provinces, 1939-41. Palgrave Macmillan, 1991, (ISBN 0-312-05570-6).

- Wacław Stachiewicz (1998). Wierności dochować żołnierskiej. OW RYTM. ISBN 83-86678-71-2.

- Zaloga, Steve, and Howard Gerrard. Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002 (ISBN 1-84176-408-6).

- Zaloga, Steve. The Polish Army 1939-1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1982 (ISBN 0-85045-417-4).

- Encyklopedia PWN 'KAMPANIA WRZEŚNIOWA 1939', last retrieved on 10 December 2005, Polish language

- Further reading:

- Template:De icon Jochen Böhler (2006). Auftakt zum Vernichtungskrieg; Die Wehrmacht in Polen 1939 (Preface to the War of Annihilation: Wehrmacht in Poland). Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. p. 288. ISBN 3-596-16307-2.

External links

- World War 2 Online Newspaper Archives - The Invasion of Poland, 1939

- The Campaign in Poland at WorldWar2 Database

- The Campaign in Poland at Achtung! Panzer

- German Statistics including September Campaign losses

- Brief Campaign losses and more statistics

- Fall Weiß - The Fall of Poland

- Agreement of Mutual Assistance Between the United Kingdom and Poland.-London, 25 August 1939.

- Poland's Defence War, a fairly detailed but possibly one sided account of the Polish defense in 1939

- Radio reports on the German invasion of Poland and Nazi broadcast claiming that Germany's action is an act of defense

- German reply to British Government's ultimatum of 3 September 1939

- Headline story on BBC: Germany invades Poland 1 September 1939.

- BBC portal dedicated to the start of WW II in Europe

- September 17, 1939 - Soviet aggression on Poland

- Halford Mackinder's Necessary War An essay describing the Polish Campaign in a larger strategic context of the war

- Invasion of Poland Template:Sr icon