Proventriculus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

The proventriculus is the glandular portion of the avian compound stomach, and a rather peculiar organ it is. There's nothing like it in mammals.<ref>Caceci, Thomas (undated). ''Proventriculus''. Source: {{cite web |url=http://education.vetmed.vt.edu/Curriculum/VM8054/Labs/Lab22/EXAMPLES/EXPROVEN.HTM |title=Example: Proventriculus |access-date=2007-12-18 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071210104632/http://education.vetmed.vt.edu/curriculum/VM8054/labs/Lab22/EXAMPLES/EXPROVEN.HTM |archive-date=2007-12-10 }} (accessed: December 18, 2007)</ref> |

The proventriculus is the glandular portion of the avian compound stomach, and a rather peculiar organ it is. There's nothing like it in mammals.<ref>Caceci, Thomas (undated). ''Proventriculus''. Source: {{cite web |url=http://education.vetmed.vt.edu/Curriculum/VM8054/Labs/Lab22/EXAMPLES/EXPROVEN.HTM |title=Example: Proventriculus |access-date=2007-12-18 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071210104632/http://education.vetmed.vt.edu/curriculum/VM8054/labs/Lab22/EXAMPLES/EXPROVEN.HTM |archive-date=2007-12-10 }} (accessed: December 18, 2007)</ref> |

||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

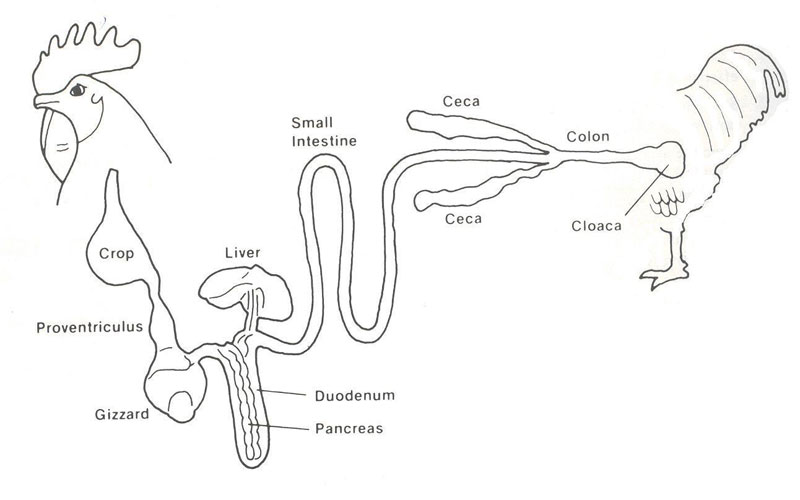

| ⚫ | [[File:Bird_Gastro_System.jpg|alt=General anatomy of the avian digestive system. The proventriculus is located early in the digestive tract, and is associated with the gizzard.|center|frame|Anatomy of the avian digestive system. The proventriculus is located early in the digestive tract, and is associated with the gizzard.]] |

||

===Secretions=== |

===Secretions=== |

||

| Line 38: | Line 40: | ||

===Motility=== |

===Motility=== |

||

The muscle contractions of the gizzard push material back into the proventriculus, which then contracts to mix materials between the stomach compartments. This transfer of digested material can occur up to 4 times per minute, and the compartments can hold the stomach contents for thirty minutes to an hour.<ref name=":0" /> The contractions are regular and rhythmical, and are more frequent in intact males than in females because there is more concentration of the hormone [[Androgen]]. This also causes castrated males to have a decrease in contractions and their amplitude. <ref name="avian"/> |

The muscle contractions of the gizzard push material back into the proventriculus, which then contracts to mix materials between the stomach compartments. This transfer of digested material can occur up to 4 times per minute, and the compartments can hold the stomach contents for thirty minutes to an hour.<ref name=":0" /> The contractions are regular and rhythmical, and are more frequent in intact males than in females because there is more concentration of the hormone [[Androgen]]. This also causes castrated males to have a decrease in contractions and their amplitude. <ref name="avian"/> |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Bird_Gastro_System.jpg|alt=General anatomy of the avian digestive system. The proventriculus is located early in the digestive tract, and is associated with the gizzard.|center|frame|Anatomy of the avian digestive system. The proventriculus is located early in the digestive tract, and is associated with the gizzard.]] |

||

===Culinary use=== |

===Culinary use=== |

||

Revision as of 14:00, 1 December 2022

The proventriculus is part of the digestive system of birds.[1] An analogous organ exists in invertebrates and insects.

Birds

The proventriculus is a standard part of avian anatomy, and is a rod shaped organ, located between the esophagus and the gizzard of most birds.[2] It is generally a glandular part of the stomach that may store and/or commence digestion of food before it progresses to the gizzard.[3] The primary function of the proventriculus is to secrete hydrochloric acid and pepsinogen into the digestive compartments that will churn the ingested material through muscular mechanisms.[4] The Encarta (2007) holds that the proventriculus is:

The first part of a bird's stomach, where digestive enzymes are mixed with food before it goes to the gizzard. It is analogous to the gizzard in insects and crustaceans.[1]

Thomas Cecere (College of Veterinary Medicine of VirginiaTech)[5] discusses the proventriculus of the avian stomach and opines that:

The proventriculus is the glandular portion of the avian compound stomach, and a rather peculiar organ it is. There's nothing like it in mammals.[6]

Secretions

The secretory glands that line the proventriculus gives it the nickname of the "true stomach," as it secretes the same components as a mammalian stomach. [7] The proventriculus contains glands that secrete HCL and pepsinogen. The gastric glands of birds only have one type of cell that produces both HCL and pepsinogen, unlike mammals which have different cell types for each of those productions.[8] Pepsinogen produces pepsin, which breaks the peptide bonds found in peptides and proteins.[9]

The distribution of the secretions differ depending on the avian species. These secretions cause the stomach to be very acidic, but the exact value will differ based on the species. [7]

| Species | pH value |

|---|---|

| Chicken | 4.8 |

| Turkey | 4.7 |

| Pigeon | 4.8 |

| Duck | 3.4 |

In petrels, the proventriculus is much larger and the mucus secretions are raised into longitudinal ridges, which creates more surface area and more concentrated cells. Petrels also have a unique mechanism where they can shoot stomach oil from their beak when alarmed [10]

Hormones also affect the amount and concentration of these secretions. Some of these include Gastrin, Bombesin, Avian Pancreatic Polypeptide, and cholecystokinin. [7]

Motility

The muscle contractions of the gizzard push material back into the proventriculus, which then contracts to mix materials between the stomach compartments. This transfer of digested material can occur up to 4 times per minute, and the compartments can hold the stomach contents for thirty minutes to an hour.[4] The contractions are regular and rhythmical, and are more frequent in intact males than in females because there is more concentration of the hormone Androgen. This also causes castrated males to have a decrease in contractions and their amplitude. [8]

Culinary use

Chicken proventriculus is eaten as street food in the Philippines. It is dipped in flour and deep fried until golden brown. It is served best with spiced vinegar and is often sold in a small kiosk. This dish is called proben.

Insects

Insects also have a proventriculus structure in their digestive track, although the function differs from avian proventriculi. They still contain secretions, but its main role is to help the passage of food and connect the crop to the stomach. [11] Hymenoptera contain sphincter muscles that add pressure on the digestive components and help pass the food into the midgut. [12] The area called the proventriculus bulb contains hairs or teeth like structures that help filter food and make it easier to digest. In ants, it is used as a barrier to increase storage capacity of the crop. [11] In bees, it helps separate nectar that will later be converted to honey, from pollen that will be digested. Male bees also can have an abnormal proventriculus conditions that prevents passage of food. [13]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Encarta World English Dictionary [North American Edition] (2007). Proventriculus. Source: "Proventriculus definition - Dictionary - MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2008-01-07. Retrieved 2007-12-18. (accessed: December 18, 2007)

- ^ Zaher, Mostafa (2012). "Anatomical, histological and histochemical adaptations of the avian alimentary canal to their food habits: I-Coturnix coturnix". Life Science Journal. 9: 252–275.

- ^ Source: "Proventriculus". Archived from the original on 2007-12-27. Retrieved 2007-12-18. (accessed: December 18, 2007)

- ^ a b Svihus, Birger (2014). "Function of the Digestive System". The Journal of Applied Poultry Research. 23 (2): 306–314. doi:10.3382/japr.2014-00937.

- ^ "Thomas Caceci". www.vetmed.vt.edu. Archived from the original on 9 October 1997. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Caceci, Thomas (undated). Proventriculus. Source: "Example: Proventriculus". Archived from the original on 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2007-12-18. (accessed: December 18, 2007)

- ^ a b c Langlois, Isabelle (2003-01-01). "The anatomy, physiology, and diseases of the avian proventriculus and ventriculus". Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice. 6 (1): 85–111. doi:10.1016/S1094-9194(02)00027-0. ISSN 1094-9194. PMID 12616835. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ a b Sturkie, Paul D. (1954). Avian physiology. Ithaca, N. Y.: Comstock. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ Moran, Edwin (2016). "Gastric digestion of protein through pancreozyme action optimizes intestinal forms for absorption, mucin formation and villus integrity". Animal Feed Science and Technology. 221: 384–303. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.05.015.

- ^ "THE ORIGIN OF STOMACH OIL IN THE PETRELS, WITH COMPARATIVE OBSERVATIONS ON THE AVIAN PROVENTRICULUS - Matthews - 1949 - Ibis - Wiley Online Library". Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ a b Flavio Henrique Caetano; Xavier Espadaler; Fernando Jose Zara (1998). Comparative Ultramorphology Of The Proventriculus Bulb Of Two Species Of Mutillidae (Hymenoptera). Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ "The evolution and social significance of the ant proventriculus. : Eisner, T. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ Ruiz-Gonzalez, Mario X. (2022). "Abnormal Proventriculus in Bumble Bee Males". Diversity-Basel. 14 (9): 775. doi:10.3390/d14090775. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)