Persecution of Jews: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

{{Blockquote |

{{Blockquote |

||

|text=Inside the towns, Jews and other dhimmis were frequently attacked, wounded, and even killed by local Muslims and Turkish soldiers. Such attacks were frequently for trivial reasons: Wilson [in British Foreign Office correspondence] recalled having met a Jew who had been badly wounded by a Turkish soldier for not having instantly dismounted when ordered to give up his donkey to a soldier of the Sultan. Many Jews were killed for less. On occasion the authorities attempted to get some form of redress but this was by no means always the case: the Turkish authorities themselves were sometimes responsible for beating Jews to death for some unproven charge. After one such occasion [British Consul] Young remarked: “I must say I am sorry and surprised that the Governor could have acted so savage a partfor certainly what I have seen of him I should have thought him superior to such wanton inhumanity—but it was a Jew without friends or protection—it serves to show well that it is not without reason that the poor Jew, even in the nineteenth century, lives from day to day in terror of his life.”...In fact, it took some time [i.e., at least a decade after the 1839 reforms] before these courts did accept dhimmi testimony in Palestine. The fact that Jews were represented on the meclis [provincial legal council] did not contribute a great deal to the amelioration of the legal position of the Jews: the Jewish representatives were tolerated grudgingly and were humiliated and intimidated to the point that they were afraid to offer any opposition to the Muslim representatives. In addition the constitution of the meclis was in no sense fairly representative of the population. In Jerusalem in the 1870s the meclis consisted of four Muslims, three Christians and only one Jewat a time when Jews constituted over half the population of the city.... Some years after the promulgation of the hatt-i-serif [Tanzimat reform edicts] Binyamin [in an eyewitness account from Eight Years in Asia and Africa from 1846 to 1855, p. 44] was still able to write of the Jews—“they are entirely destitute of every legal protection.”...Perhaps even more to the point, the courts were biased against the Jews and even when a case was heard in a properly assembled court where dhimmi testimony was admissible the court would still almost invariably rule against the Jews. It should be noted that a non-dhimmi [e.g., foreign] Jew was still not permitted to appear and witness in either the mahkama [specific Muslim council] or the meclis.|}} |

|text=Inside the towns, Jews and other dhimmis were frequently attacked, wounded, and even killed by local Muslims and Turkish soldiers. Such attacks were frequently for trivial reasons: Wilson [in British Foreign Office correspondence] recalled having met a Jew who had been badly wounded by a Turkish soldier for not having instantly dismounted when ordered to give up his donkey to a soldier of the Sultan. Many Jews were killed for less. On occasion the authorities attempted to get some form of redress but this was by no means always the case: the Turkish authorities themselves were sometimes responsible for beating Jews to death for some unproven charge. After one such occasion [British Consul] Young remarked: “I must say I am sorry and surprised that the Governor could have acted so savage a partfor certainly what I have seen of him I should have thought him superior to such wanton inhumanity—but it was a Jew without friends or protection—it serves to show well that it is not without reason that the poor Jew, even in the nineteenth century, lives from day to day in terror of his life.”...In fact, it took some time [i.e., at least a decade after the 1839 reforms] before these courts did accept dhimmi testimony in Palestine. The fact that Jews were represented on the meclis [provincial legal council] did not contribute a great deal to the amelioration of the legal position of the Jews: the Jewish representatives were tolerated grudgingly and were humiliated and intimidated to the point that they were afraid to offer any opposition to the Muslim representatives. In addition the constitution of the meclis was in no sense fairly representative of the population. In Jerusalem in the 1870s the meclis consisted of four Muslims, three Christians and only one Jewat a time when Jews constituted over half the population of the city.... Some years after the promulgation of the hatt-i-serif [Tanzimat reform edicts] Binyamin [in an eyewitness account from Eight Years in Asia and Africa from 1846 to 1855, p. 44] was still able to write of the Jews—“they are entirely destitute of every legal protection.”...Perhaps even more to the point, the courts were biased against the Jews and even when a case was heard in a properly assembled court where dhimmi testimony was admissible the court would still almost invariably rule against the Jews. It should be noted that a non-dhimmi [e.g., foreign] Jew was still not permitted to appear and witness in either the mahkama [specific Muslim council] or the meclis.|}} |

||

In the early twentieth century Nahum Slousch observed at Bu Zein, in the Jabal Gharian in Libya, that it was customary for muslim children to throw stones at Jewish passersby.<ref>https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Decline_of_Eastern_Christianity_Unde/doeTXF9axosC?hl=en</ref> |

|||

==Nazism== |

==Nazism== |

||

Revision as of 00:57, 5 January 2023

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| Freedom of religion |

|---|

| Religion portal |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

The persecution of Jews has been a major event in Jewish history, prompting shifting waves of refugees and the formation of diaspora communities. As early as 605 BCE, Jews who lived in the Neo-Babylonian Empire were persecuted and deported. Antisemitism was also practiced by the governments of many different empires (Roman empire) and the adherents of many different religions (Christianity), and it was also widespread in many different regions of the world (Middle East and Islamic). Jews were commonly used as scapegoats for tragedies and shortcomings such as those which were seen in the Black Death Persecutions, the 1066 Granada Massacre, the Massacre of 1391 in Spain, the many Pogroms in the Russian Empire, and the tenets of Nazism prior to and during World War II, which lead to The Holocaust and the murder of six million Jews.

Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Babylonian captivity or the Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their defeat in the Jewish–Babylonian War and the destruction of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. The event is described in the Hebrew Bible, and its historicity is supported by archaeological and non-biblical evidence.

After the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BCE, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II besieged Jerusalem, which resulted in tribute being paid by the Judean king Jehoiakim.[1] In the fourth year of Nebuchadnezzar II's reign, Jehoiakim refused to pay further tribute, which led to another siege of the city in Nebuchadnezzar II's seventh year that culminated in the death of Jehoiakim and the exile to Babylonia of his successor Jeconiah, his court and many others; Jeconiah's successor Zedekiah and others were exiled in Nebuchadnezzar II's 18th year; a later deportation occurred in Nebuchadnezzar II's 23rd year. The dates, numbers of deportations, and numbers of deportees given in the biblical accounts vary.[2] These deportations are dated to 597 BCE for the first, with others dated at 587/586 BCE, and 582/581 BCE respectively.[3]

Seleucids

When Judea fell under the authority of the Seleucid Empire, the process of Hellenization was enforced by law.[4] This effectively meant requiring pagan religious practice.[5][6] In 167 BCE Jewish sacrifice was forbidden, sabbaths and feasts were banned and circumcision was outlawed. Altars to Greek gods were set up and animals prohibited to Jews were sacrificed on them. The Olympian Zeus was placed on the altar of the Temple. Possession of Jewish scriptures was made a capital offense.

Roman Empire

The Jewish Encyclopaedia refers to the persecution of Jews and the paganization of Jerusalem during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD):

The Jews now passed through a period of bitter persecution: Sabbaths, festivals, the study of the Torah and circumcision were interdicted, and it seemed as if Hadrian desired to annihilate the Jewish people. His anger fell upon all the Jews of his empire, for he imposed upon them an oppressive poll-tax. The persecution, however, did not last long, for Antoninus Pius (138-161) revoked the cruel edicts.[7]

Western and Christian antisemitism

In the Middle Ages antisemitism in Europe was religious. Many Christians, including members of the clergy, held the Jewish people collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus. As stated in the Boston College Guide to Passion Plays, "Over the course of time, Christians began to accept … that the Jewish people as a whole were responsible for killing Jesus. According to this interpretation, both the Jews present at Jesus Christ's death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time, have committed the sin of deicide, or 'god-killing'. For 1900 years of Christian-Jewish history, the charge of deicide has led to hatred, violence against and murder of Jews in Europe and America."[8]

During the High Middle Ages in Europe there was full-scale persecution of Jews in many places, with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions and massacres. An underlying source of prejudice against Jews in Europe was religious. Jews were frequently massacred and exiled from various European countries. The persecution reached its first peak during the Crusades. In the First Crusade (1096), flourishing communities on the Rhine and the Danube were utterly destroyed, a prime example being the Rhineland massacres. In the Second Crusade (1147) the Jews in France were subject to frequent massacres. The Jews were also subjected to attacks by the Shepherds' Crusades of 1251 and 1320. The Crusades were followed by expulsions, including in 1290, the banishing of all English Jews; in 1396, 100,000 Jews were expelled from France; and, in 1421 thousands were expelled from Austria. Many of the expelled Jews fled to Poland.[9]

As the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than a half of the population, Jews were taken as scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence in the Black Death persecutions. Although Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by papal bull on July 6, 1348 - with another following later in 1348 - several months afterwards, 900 Jews were burnt alive in Strasbourg, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city.[10]

One study finds that persecutions and expulsions of Jews increased with negative economic shocks and climatic variations in Europe during the period from 1100–1600.[11] The authors of the study argue that this stems from people blaming Jews for misfortunes and weak rulers going after Jewish wealth in times of fiscal crisis. The authors propose several explanations for why Jewish persecutions significantly declined after 1600:

- (1) there were simply fewer Jewish communities to persecute by the 17th century;

- (2) improved agricultural productivity, or, better-integrated markets may have reduced vulnerability to temperature shocks;

- (3) the rise of stronger states may have led to more robust protection for religious and ethnic minorities;

- (4) there were fewer negative temperature shocks.

- (5) the impact of the Reformation and the Enlightenment may have reduced anti-semitic attitudes.[11]

In the Papal States, which existed until 1870, Jews were required to live only in specified neighborhoods which were called ghettos. Until the 1840s, they were required to regularly attend sermons urging their conversion to Christianity. Only Jews were taxed to support state boarding schools for Jewish converts to Christianity. It was illegal to convert from Christianity to Judaism. Sometimes Jews were baptized involuntarily, and, even when such baptisms were illegal, forced to practice the Christian religion. In many such cases, the state separated them from their families; the Edgardo Mortara account is one of the most widely publicized instances of acrimony between Catholics and Jews in the Papal States in the second half of the 19th century.

Middle East and Islamic antisemitism

According to Mark R. Cohen, during the rise of Islam, the first encounters between Muslims and Jews resulted in friendship when the people of Medina gave Muhammad refuge, among them were Jewish tribes of Medina. Conflict arose when Muhammad expelled certain Jewish tribes after they refused to swear their allegiance to him and aided the Meccan Pagans. He adds that this encounter was an exception rather than a rule.[12]

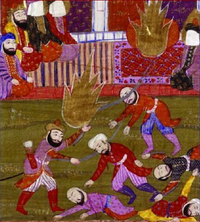

Of the three Jewish tribes of Medina, the Banu Nadir and the Banu Qaynuqa were expelled in the course of Muhammad's rule after suspicion arose in the Muslim leadership that the Jews were planning the assassination of Muhammad. On the other hand, the Banu Qurayza tribe was eliminated by Muhammad in the aftermath of the Battle of the Trench. The tribe was accused of colluding with Meccan enemies during the Meccan siege of Medina and subsequently besieged. When they surrendered, all grown men were executed and women and children were enslaved.[13][14] Muhammad is recorded as saying that he would expel all Jews and Christians from Arabia,[15] although this was not carried out until the reign of Umar.[16]

Traditionally, Jews living in Islamic states were subjected to the status of dhimmi, therefore they were allowed to practice their religion and administer their internal affairs but were subjects to certain conditions.[17] They had to pay the jizya (a per capita tax imposed on free adult non-Muslim males) to Muslims.[17] Dhimmis had an inferior status under Islamic rule. They had several social and legal disabilities such as prohibitions against bearing arms or giving testimony in courts in cases involving Muslims.[18] Contrary to popular belief, the Qur'an did not order Muslims to force Jews to wear distinctive clothing. Obadiah the Proselyte reported in 1100 AD, that the Caliph had created this rule himself.[19]

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Resentment toward Jews perceived as having attained too lofty a position in Islamic society also fueled antisemitism and massacres. In Moorish Spain, ibn Hazm and Abu Ishaq focused their anti-Jewish writings on this allegation. This was also the chief motivation behind the 1066 Granada massacre, when "[m]ore than 1,500 Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons, fell in one day",[20] and in Fez in 1033, when 6,000 Jews were killed.[21] There were further massacres in Fez in 1276 and 1465.[22]

In the Zaydi imamate of Yemen, Jews were singled out for discrimination in the 17th century, which culminated in the general expulsion of all Jews from places in Yemen to the arid coastal plain of Tihamah, and which became known as the Mawza Exile.[23]

The Damascus affair occurred in 1840 when a French monk and his servant disappeared in Damascus. Immediately following, a charge of ritual murder was brought against a large number of Jews in the city including children who were tortured. The consuls of the United Kingdom, France and Germany as well as Ottoman authorities, Christians, Muslims and Jews all played a great role in this affair.[24]

There was a massacre of Jews in Baghdad in 1828.[21] There was another massacre in Barfurush in 1867.[21]

In 1839, in the eastern Persian city of Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue, and destroyed the Torah scrolls. This is known as the Allahdad incident. Between 30 and 40 people were killed, and it was only by forcible conversion that a large-scale massacre was averted.[25]

In Palestine there were riots and pogroms against Jews in 1920 and 1921. Tensions over the Western Wall in Jerusalem led to the 1929 Palestine riots,[26] whose main victims were the ancient Jewish community at Hebron.

In 1941, following Rashid Ali's pro-Axis coup, riots known as the Farhud broke out in Baghdad in which approximately 180 Jews were killed and about 240 were wounded, 586 Jewish-owned businesses were looted and 99 Jewish houses were destroyed.[27]

During the Holocaust, the Middle East was in turmoil. Britain prohibited Jewish immigration to the British Mandate of Palestine. In Cairo the Jewish Lehi (also known as the Stern Gang) assassinated Lord Moyne in 1944 fighting as part of its campaign against British closure of Palestine to Jewish immigration, complicating British-Arab-Jewish relations. While the Allies and the Axis were fighting for the oil-rich region, the Mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husayni staged a pro-Nazi coup in Iraq and organized the Farhud pogrom that marked the turning point for about 150,000 Iraqi Jews who, following this event and the hostilities generated by the war with Israel in 1948, were targeted for violence, persecution, boycotts, confiscations, and near complete expulsion in 1951. The coup failed and the mufti fled to Berlin, where he actively supported Hitler. In Egypt, with a Jewish population of about 75,000, young Anwar Sadat was imprisoned for conspiring with the Nazis and promised them that "no British soldier would leave Egypt alive" (see Military history of Egypt during World War II) leaving the Jews of that region defenseless. In the French Vichy territories of Algeria and Syria, plans were drawn up for the liquidation of their Jewish populations if the Axis powers were triumphant.

Tensions caused by the Arab–Israeli conflict were a factor in the rise of animosity towards the Jewish people all over the Middle East, as hundreds of thousands of Jews fled as refugees, the main waves fleeing soon after the 1948 and 1956 wars. In reaction to the Suez Crisis of 1956, the Egyptian government expelled almost 25,000 Egyptian Jews and confiscated their property, and sent approximately 1,000 more Jews to prisons and detention camps. The population of the Jewish communities in Muslim Middle East and North Africa was reduced from about 900,000 in 1948 to less than 8,000 today.

On March 2, 1974, the bodies of four Syrian Jewish girls were discovered by border police in a cave in the Zabdani Mountains northwest of Damascus. Fara Zeibak, 24, her sisters, Lulu Zeibak, 23, Mazal Zeibak, 22 and their cousin, Eva Saad, 18, had contracted with a band of smugglers to flee from Syria to Lebanon and eventually to Israel. The girls' bodies were found raped, murdered and mutilated. The police also found the remains of two Jewish boys, Natan Shaya 18 and Kassem Abadi 20, victims of an earlier massacre.[28] Syrian authorities deposited the bodies of all six in sacks before the homes of their parents in the Jewish ghetto in Damascus.[29]

Ottoman Empire

The Jews suffered during the Ottoman conquests and policies of colonization and population transfers (the surgun system). This resulted in the disappearance of several Jewish communities, including Salonica, and their replacement by Jewish refugees from Spain. Joseph R. Hacker observes:[30]

We posses letters written about the fate of Jews who underwent one or another of the Ottoman conquests. In one of the letters which was written before 1470, there is a description of the fate of such a Jew and his community, according to which description, written in Rhodes and sent to Crete, the fate of the Jews was not different from that of Christians. Many were killed; others were taken captive, and children were [enslaved, forcibly converted to Islam, and] brought to Devshirme.... Some letters describe the carrying of the captive Jews to Istanbul and are filled with anti-Ottoman sentiments. Moreover, we have a description of the fate of a Jewish doctor and homilist from Veroia (Kara-Ferya) who fled to Negroponte when his community was driven into exile in 1455. He furnished us witha description of the exiles and their forced passage to Istanbul. Later on we find him at Istanbul itself, and in a homily delivered there in 1468 he expressed his anti-Ottoman feelings openly. We also have some evidence that the Jews of Constantinople suffered from the conquest of the city and that several were sold into slavery.

Hacker concludes that The friendly policies of Mehmed and the good reception by Bayezid II of Spanish Jews likely caused 16th century Jewish writers to overlook both the destruction Byzantine Jews suffered during the Ottoman conquests and the later outbursts of oppression under Bayezid II and Selim I.

Sultan Murad IV feared that the ottoman decline was a punishment from from Allah for being lax on the enforcement of the Sharia. In 1631 He issued a decree re-enforcing the dress restrictions for dhimmis, to ensure they would “feel themselves subdued” (Qur’an 9:29):[31]

Insult and humiliate infidels in garment, clothing and manner of dress according to Muslim law and imperial statute. Henceforth, do not allow them to mount a horse, wear sable fur, sable fur caps, satin and silk velvet. Do not allow their women to wear mohair caps wrapped in cloth and “Paris” cloth. Do not allow infidels and Jews to go about in Muslim manner and garment. Hinder and remove these kinds. Do not lose a minute in executing the order that I have proclaimed in this manner.

When a fire devasated much of Constantinople in 1660, the Ottomans blamed the Jews and expelled them from the city. Inscribed in the royal mosque in Constantinople was a reference to Prophets Muhammad’s expulsion of the Jews from Medina; the mosque’s endowment deed has a reference to "the Jews who are the enemy of Islam."[31]

Tudor Parfitt made these observations in his srudy of jews under the Ottomans in the 19th Palestine:[32]

Inside the towns, Jews and other dhimmis were frequently attacked, wounded, and even killed by local Muslims and Turkish soldiers. Such attacks were frequently for trivial reasons: Wilson [in British Foreign Office correspondence] recalled having met a Jew who had been badly wounded by a Turkish soldier for not having instantly dismounted when ordered to give up his donkey to a soldier of the Sultan. Many Jews were killed for less. On occasion the authorities attempted to get some form of redress but this was by no means always the case: the Turkish authorities themselves were sometimes responsible for beating Jews to death for some unproven charge. After one such occasion [British Consul] Young remarked: “I must say I am sorry and surprised that the Governor could have acted so savage a partfor certainly what I have seen of him I should have thought him superior to such wanton inhumanity—but it was a Jew without friends or protection—it serves to show well that it is not without reason that the poor Jew, even in the nineteenth century, lives from day to day in terror of his life.”...In fact, it took some time [i.e., at least a decade after the 1839 reforms] before these courts did accept dhimmi testimony in Palestine. The fact that Jews were represented on the meclis [provincial legal council] did not contribute a great deal to the amelioration of the legal position of the Jews: the Jewish representatives were tolerated grudgingly and were humiliated and intimidated to the point that they were afraid to offer any opposition to the Muslim representatives. In addition the constitution of the meclis was in no sense fairly representative of the population. In Jerusalem in the 1870s the meclis consisted of four Muslims, three Christians and only one Jewat a time when Jews constituted over half the population of the city.... Some years after the promulgation of the hatt-i-serif [Tanzimat reform edicts] Binyamin [in an eyewitness account from Eight Years in Asia and Africa from 1846 to 1855, p. 44] was still able to write of the Jews—“they are entirely destitute of every legal protection.”...Perhaps even more to the point, the courts were biased against the Jews and even when a case was heard in a properly assembled court where dhimmi testimony was admissible the court would still almost invariably rule against the Jews. It should be noted that a non-dhimmi [e.g., foreign] Jew was still not permitted to appear and witness in either the mahkama [specific Muslim council] or the meclis.

In the early twentieth century Nahum Slousch observed at Bu Zein, in the Jabal Gharian in Libya, that it was customary for muslim children to throw stones at Jewish passersby.[33]

Nazism

The persecution of Jews reached its most destructive form in the policies of Nazi Germany, which made the destruction of Jews a high priority, starting with the persecution of Jews and culminating in the killing of approximately 6,000,000 Jews during World War II and the Holocaust from 1941 to 1945.[34] Originally, the Nazis used death squads, the Einsatzgruppen, to conduct massive open-air killings of Jews who lived in the territories that they conquered. By 1942, the Nazi leadership decided to implement the Final Solution, the genocide of the Jews of Europe, and increase the pace of the Holocaust by establishing extermination camps for the specific purpose of killing Jews as well as other undesirables such as people who openly opposed Hitler.[35][36]

This was an industrial method of genocide. Millions of Jews who had been confined to disease-ridden and massively overcrowded ghettos were transported (often by train) to death camps, where some of them were herded into a specific location (often a gas chamber), then they were either gassed or shot to death. Other prisoners simply committed suicide, unable to go on after witnessing the horrors of camp life. Afterward, their bodies were often searched for any valuable or useful materials, such as gold fillings or hair, and then their remains were either buried in mass graves or burned. Others were interned in the camps and during their internment, they were given little food and disease was rampant.[37]

Escapes from the camps were few, but they were not unknown. The few escapes from Auschwitz that succeeded were made possible by the Polish underground which operated inside the camp and local people who lived outside.[38] In 1940, the Auschwitz commandant reported that "the local population is fanatically Polish and … prepared to take any action against the hated SS camp personnel. Every prisoner who managed to escape can count on help the moment he reaches the wall of the first Polish farmstead."[39]

Russia and the Soviet Union

Tsarist Russia

For much of the 19th century, Imperial Russia, which included much of Poland, Ukraine, Moldova and the Baltic states, contained the world's largest Jewish population. From Alexander III's reign until the end of Tsarist rule in Russia, many Jews were often restricted to the Jewish Pale of Settlement and they were also banned from many jobs and locations. Jews were subject to racist laws, such as the May Laws, and they were also targeted in hundreds of violent anti-Jewish riots, called pogroms, which received unofficial state support. During this period a hoax document alleging a global Jewish conspiracy, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, was published.

The Tsarist government implemented policies that ensured that the Jews would remain isolated. However, the government tolerated the existence of their religious and national institutions and it also allowed them to emigrate. The restrictions and discriminatory laws drove many Russian Jews to embrace liberal and socialist causes. However, following the Russian Revolution, many politically active Jews forfeited their Jewish identity.[40] According to Leon Trotsky, "[Jews] considered themselves neither Jews nor Russians but socialists. To them, Jews were not a nation but a class of exploiters whose fate it was to dissolve and assimilate." In the aftermath of the overthrow of Tsarist Russia, Jews found themselves in a tragic predicament. Conservative Russians saw them as a disloyal and subversive element, while the radicals viewed the Jews as a doomed social class.[40]

Soviet Union

Even though many of the Old Bolsheviks were ethnically Jewish, they sought to uproot Judaism and Zionism and in order to achieve this goal, they established the Yevsektsiya. By the end of the 1940s, the Communist leadership of the former USSR had liquidated almost all Jewish organizations, with the exception of a few token synagogues. These synagogues were then placed under police surveillance, both openly and through the use of informants.[citation needed]

The campaign of 1948–1953 against so-called "rootless cosmopolitans," the alleged "Doctors' plot," the rise of "Zionology" and subsequent activities of official organizations such as the Anti-Zionist committee of the Soviet public were officially carried out under the banner of "anti-Zionism", and by the mid-1950s the state persecution of Soviet Jews emerged as a major human rights issue in the West as well as domestically.

Apartheid South Africa

During the 1930s, many Nationalist Party leaders and wide sections of the Afrikaner people strongly came under the influence of the Nazi movement that dominated Germany from 1933 to 1945. There were many reasons for this. Germany was the traditional enemy of Britain, and whoever opposed Britain was seen as a friend of the Nationalists. Many Nationalists, moreover, believed that the opportunity to re-establish their lost republic would come with the defeat of the British Empire in the international arena. The more belligerent Hitler became, the higher hopes rose that a new era of Afrikanerdom was about to dawn.[41]

The National Party of D F Malan closely associated itself with the policies of the Nazis. Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe was controlled under the Aliens Act and it soon came to an end during this period. Although Jews were accorded status as Europeans, they were not accepted into white society. Many Jews lived in mixed race areas such as District Six, from where they were forcibly removed in order to make way for a whites-only development.[citation needed]

During the 1930s, the Nationalists found much in common with the 'South African Gentile National Socialist Movement', headed by Johannes von Strauss von Moltke, whose objective was to combat and destroy the alleged 'perversive influence of the Jews in economics, culture, religion, ethics and statecraft, and re-establish European Aryan control in South Africa for the welfare of the Christian peoples of South Africa'.[41]

During the 1960s, Oswald Mosley, the British fascist leader, was a frequent visitor to South Africa, where he was received by the Prime Minister and other members of the Cabinet. At one time, Mosley had two functioning branches of his organization in South Africa, and one of his supporters, Derek Alexander, was stationed in Johannesburg as his main agent.[citation needed]

Upon Verwoerd's assassination in 1966, BJ Vorster was elected by the National Party to replace him. While Vorster had been a supporter of Hitler during WWII, his policy towards Jews in his own country, however, can best be described as ambivalent.[citation needed]

The 1980s saw the rise of far-right neo-Nazi groups such as the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging under Eugene Terreblanche. The AWB modeled itself after Hitler's National Socialist Party replete with fascist regalia and an emblem resembling the swastika.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Coogan, Michael (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel S Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 357–58. ISBN 978-0802862600. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

Overall, the difficulty in calculation arises because the biblical texts provide varying numbers for the different deportations. The HB/OT's conflicting figures for the dates, number and victims of the Babylonian deportations become even more of a problem for historical reconstruction because, other than the brief reference to the first capture of Jerusalem (597) in the Babylonian Chronicle, historians have only the biblical sources with which to work.

- ^ Dunn, James G.; Rogerston, John William (2003). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 545. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- ^ VanderKam, James C. (2001). An Introduction to Early Judaism. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans. pp. 18–24. ISBN 978-0-8028-4641-9.

- ^ "An Introduction to Early Judaism - 2001, Page viii by James C. Vanderkam". Archived from the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ "missing".[dead link]

- ^ "HADRIAN - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). 2011-03-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-01. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ "Why the Jews? – Black Death". Holocaustcenterpgh.net. Archived from the original on 2007-04-29. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, La plus grande épidémie de Histoire ("The greatest epidemics in history"), in L'Histoire magazine, n°310, June 2006, p.47 (in French)

- ^ a b Anderson, Robert Warren; Johnson, Noel D.; Koyama, Mark (2015-09-01). "Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800". The Economic Journal. 127 (602): 924–958. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12331. hdl:2027.42/137319. ISSN 1468-0297. S2CID 4610493.

- ^ Cohen, Mark R. Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 163. ISBN 0-691-01082-X

- ^ Kister, "The Massacre of the Banu Quraiza", p. 95f.

- ^ Rodinson, Muhammad: Prophet of Islam, p. 213.

- ^ Sahih Muslim, 19:4366

- ^ Giorgio Levi Della Vida and Michael Bonner, Encyclopaedia of Islam, and Madelung, The Succession to Prophet Muhammad, p. 74

- ^ a b Lewis (1984), pp.10,20

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp. 9,27

- ^ Scheiber, A. (1954) "The Origins of Obadiah, the Norman Proselyte" Journal of Jewish Studies London: Oxford University Press. v.5. p.37

- ^ "GRANADA - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ a b c Morris, Benny (2001) Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist–Arab Conflict, 1881–2001. New York:Vintage Books. pp.10–11.

- ^ Gerber (1986), p. 84

- ^ Qafiḥ, Yossef (1989) Ketavim (Collected Papers), c.2, Jerusalem, Israel. pp.714-ff. (Hebrew)

- ^ Frankel, Jonathan (1997) The Damascus Affair: 'Ritual Murder', Politics, and the Jews in 1840 Cambridge, UK:Cambridge University Press. p.1. ISBN 0-521-48396-4

- ^ Patai, Raphael (1997). Jadid al-Islam: The Jewish "New Muslims" of Meshhed. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2652-7.

- ^ Ovendale, Ritchie (2004). "The "Wailing Wall" Riots". The Origins of the Arab–Israeli Wars. Pearson Education. pp. g.71. ISBN 978-0-58282320-4.

The Mufti tried to establish Muslim rights and the Jews were deliberately antagonized by building works and noise.

- ^ Levin, Itamar (2001. Locked Doors: The Seizure of Jewish Property in Arab Countries. Praeger/Greenwood. p.6. ISBN 0-275-97134-1

- ^ Friedman, Saul S. (1989). Without Future: The Plight of Syrian Jewry. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-93313-5

- ^ Le Figaro, March 9, 1974, "Quatre femmes juives assassins a Damas," (Paris: International Conference for Deliverance of Jews in the Middle East, 1974), p. 33.

- ^ Braude, Benjamin (2014). Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-58826-865-5.

- ^ a b Finkel, Caroline (2012-07-19). Osman's Dream. John Murray Press. ISBN 978-1-84854-785-8.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Jews_in_Palestine_1800_1882.html?id=BOdtQgAACAAJ&redir_esc=y

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Decline_of_Eastern_Christianity_Unde/doeTXF9axosC?hl=en

- ^ Dawidowicz, Lucy. The War Against the Jews, Bantam, 1986.p. 403

- ^ Manvell, Roger Goering New York:1972 Ballantine Books – War Leader Book #8 Ballantine's Illustrated History of the Violent Century

- ^ "Ukrainian mass Jewish grave found". BBC News. 2007-06-05. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know," United States Holocaust Museum, 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Linn, Ruth. Escaping Auschwitz. A culture of forgetting, Cornell University Press, 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Swiebocki, Henryk. "Prisoner Escapes," in Berenbaum, Michael & Gutman, Yisrael (eds). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, Indiana University Press and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1994, p. 505.

- ^ a b Pipes, Daniel (December 1989). "The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917, by Nora Levin; The Jews of the Soviet Union, by Benjamin Pinkus". Commentary. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ a b "The Rise of the South African Reich - Chapter 4". 15 July 2007. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007.

Bibliography

- Lewis, Bernard (1984) The Jews of Islam. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00807-8

External links

Media related to Persecution of Jews at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Persecution of Jews at Wikimedia Commons