Bowel resection: Difference between revisions

Fixed reference date error(s) (see CS1 errors: dates for details) and AWB general fixes |

Add anatomy section |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|} |

||

[[File:The principles and practice of surgery (1916) (14763802462).jpg|alt=Illustration of resection of bowel segment as performed in the early 1900s.|thumb|Small bowel resection]] |

|||

== Anatomy == |

|||

The anatomy and surgical technique for bowel resection varies based on the location of the removed segment and whether or not the surgery is due to malignancy. |

|||

== Medical Indications == |

== Medical Indications == |

||

Revision as of 01:50, 12 March 2023

| Bowel resection | |

|---|---|

Drawing showing bowel resection for colon cancer | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

A bowel resection or enterectomy (enter- + -ectomy) is a surgical procedure in which a part of an intestine (bowel) is removed, from either the small intestine or large intestine. Often the word enterectomy is reserved for the sense of small bowel resection, in distinction from colectomy, which covers the sense of large bowel resection. Bowel resection may be performed to treat gastrointestinal cancer, bowel necrosis, severe enteritis, diverticular disease, Crohn's disease, endometriosis, ulcerative colitis, or bowel obstruction due to scar tissue. Other reasons to perform bowel resection include traumatic injuries and to remove polyps when polypectomy is insufficient, either to prevent polyps from ever becoming cancerous or because they are causing or threatening bowel obstruction, such as in familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, or other polyposis syndromes.[1] Some patients require ileostomy or colostomy after this procedure as alternative means of excretion.[1] Depending on which part and how much of the intestines are removed, there may be digestive and metabolic challenges afterward, such as short bowel syndrome.

Types

Types of enterectomy are named according to the relevant bowel segment:

| Procedure | Bowel segment | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| duodenectomy | duodenum | |

| Whipple | duodenum and Pancreas | |

| jejunectomy | jejunum | |

| ileectomy | ileum | |

| colectomy | colon |

Anatomy

The anatomy and surgical technique for bowel resection varies based on the location of the removed segment and whether or not the surgery is due to malignancy.

Medical Indications

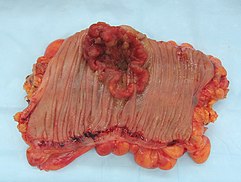

Cancer

Small bowel or colon cancer may require surgical resection.[2]

Small bowel cancer often presents late in the course due to non-specific symptoms and has poor survival rates. Risk factors for small bowel cancer include genetically inherited polyposis syndromes, age over sixty years, and history of Crohn's or Celiac disease. Cases that present before stage IV show survival benefit from surgical resection with clear margins. It is recommended that surgical resection also include lymph node sampling of a minimum of 12 nodes with some groups extolling more extensive resection. When evaluation determines cancer to be stage IV, surgical intervention is no longer curative, and is only used for symptom relief.[2]

Colon cancer is the third most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer death in the USA.[3] Due to its prevalence, screening protocols have been created for prevention of disease. Screening colonoscopies with or without polypectomy have been shown to decrease cancer morbidity and mortality.[4] When cancer is more advanced and polypectomy is not possible surgical resection is necessary. Using imaging and pathologic evaluation of resected tissue the tumor may be staged using AJCC stages.[4] Surgical resection of tumors for staging and for curative purposes requires removal of local blood vessel and lymph nodes. Standard lymph node resection includes three consecutive levels of lymph nodes and is known as a D3 lymphadenectomy.[5] In addition to surgery adjuvant chemotherapy may be used to decrease risk of recurrence. Chemotherapy is standard with stage III cancer, case dependant in stage II and palliative in stage IV.[6]

Bowel obstruction.

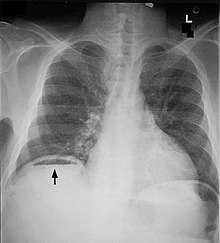

Bowel obstructions are commonly secondary to adhesions, hernias, or cancer. Bowel obstruction can be an emergency requiring immediate surgery. Original testing and imaging include blood tests for electrolyte levels, and abdominal X-rays or CT scans. Treatment often begins with IV fluids to correct electrolyte imbalances. Obstructions may be complicated by ischemia or perforation of the bowel. These cases are surgical emergencies and often require bowel resection to remove the cause of obstruction.[7] Adhesions are a common causes of obstruction, and frequently resolve without surgery.[8]

Other causes of bowel obstruction include volvulus, strictures, inflammation and intussusception. This is not an exhaustive list.

Perforation

Bowel perforation presents with abdominal pain, free air in the abdomen on standing X-ray, and sepsis.[9][10][11] Depending on the cause and size, perforations may be medically or surgically managed. Some common causes of perforation are cancer, diverticulitis, and peptic ulcer disease.

When caused by cancer, bowel perforation typically requires surgery, including resection of blood and lymph supply to the cancerous area when possible. When perforation is at the site of the tumor, the perforation may be contained in the tumor and self resolve without surgery. However, surgery may be required later for the malignancy itself. Perforation before the tumor usually requires immediate surgery due to release of fecal material into the abdomen and infection.[9]

Perforated diverticulitis often requires surgery due to risks of infection or recurrence. Recurrent diverticulitis may required resection even in the absence of perforation. Bowel resection or repair is typically initiated earlier in patients with signs of infection, the elderly, immunocompromised, and those with severe comorbidities.[10]

Peptic ulcer disease may cause perforation of the bowel but rarely requires bowel resection. Peptic ulcer disease is caused by stomach acid overwhelming the protection of mucous production. Risk factors include H. pylori infection, smoking, and NSAID use. The standard treatment is medical management, endoscopy followed by surgical omental patch repair. In rare cases where omental patch fails bowel resection may become necessary.[11]

Traumatic injuries, whether blunt force such as car accidents or penetrating wounds such as gunshot wounds, or stabbings, may also cause bowel perforation or ischemia requiring emergency surgery. Initial evaluation in trauma includes a FAST ultrasound exam followed by contrast CT abdomen in stable patients. The most common bowel injury in trauma is perforation and is repaired rather than resected if the injury involves less than half the bowel circumference and does not involve loss of blood supply. Resection is indicated with more extensive or ischemic injuries.[12]

Ischemia

Bowel ischemia is caused by decreased or absent blood flow through the Celiac, Superior Mesenteric, and Inferior Mesenteric arteries or any combination thereof. Untreated acute mesenteric ischemia can cause bowel necrosis in the affected area. This requires emergent surgery as survival without endovascular or operative intervention is around 50%. Ischemic bowel injury often requires multiple surgeries days apart to allow bowel recovery and increase odds of successful anastomosis.[13]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Small bowel resection". MedlinePlus: U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ a b Chen, Emerson Y.; Vaccaro, Gina M. (September 4, 2018). "Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 31 (5): 267–277. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1660482. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 6123009. PMID 30186048.

- ^ Holt, Peter R.; Kozuch, Peter; Mewar, Seetal (2009). "Colon cancer and the elderly: from screening to treatment in management of GI disease in the elderly". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology. 23 (6): 889–907. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2009.10.010. ISSN 1532-1916. PMC 3742312. PMID 19942166.

- ^ a b Freeman, Hugh James (2013-12-14). "Early stage colon cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (46): 8468–8473. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8468. ISSN 2219-2840. PMC 3870492. PMID 24379564.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Okuno, Kiyotaka (2007). "Surgical treatment for digestive cancer. Current issues - colon cancer". Digestive Surgery. 24 (2): 108–114. doi:10.1159/000101897. ISSN 0253-4886. PMID 17446704.

- ^ Leichsenring, Jona; Koppelle, Adrian; Reinacher-Schick, Ank (May 2014). "Colorectal Cancer: Personalized Therapy". Gastrointestinal Tumors. 1 (4): 209–220. doi:10.1159/000380790. ISSN 2296-3774. PMC 4668783. PMID 26676107.

- ^ Jackson, Patrick G.; Raiji, Manish T. (2011-01-15). "Evaluation and management of intestinal obstruction". American Family Physician. 83 (2): 159–165. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 21243991.

- ^ Tong, Jia Wei Valerie; Lingam, Pravin; Shelat, Vishalkumar Girishchandra (2020). "Adhesive small bowel obstruction - an update". Acute Medicine & Surgery. 7 (1): e587. doi:10.1002/ams2.587. ISSN 2052-8817. PMC 7642618. PMID 33173587.

- ^ a b Pisano, Michele; Zorcolo, Luigi; Merli, Cecilia; Cimbanassi, Stefania; Poiasina, Elia; Ceresoli, Marco; Agresta, Ferdinando; Allievi, Niccolò; Bellanova, Giovanni; Coccolini, Federico; Coy, Claudio; Fugazzola, Paola; Martinez, Carlos Augusto; Montori, Giulia; Paolillo, Ciro (2018). "2017 WSES guidelines on colon and rectal cancer emergencies: obstruction and perforation". World journal of emergency surgery: WJES. 13: 36. doi:10.1186/s13017-018-0192-3. ISSN 1749-7922. PMC 6090779. PMID 30123315.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Nascimbeni, R.; Amato, A.; Cirocchi, R.; Serventi, A.; Laghi, A.; Bellini, M.; Tellan, G.; Zago, M.; Scarpignato, C.; Binda, G. A. (February 2021). "Management of perforated diverticulitis with generalized peritonitis. A multidisciplinary review and position paper". Techniques in Coloproctology. 25 (2): 153–165. doi:10.1007/s10151-020-02346-y. ISSN 1128-045X. PMC 7884367. PMID 33155148.

- ^ a b Chung, Kin Tong; Shelat, Vishalkumar G. (2017-01-27). "Perforated peptic ulcer - an update". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 9 (1): 1–12. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v9.i1.1. ISSN 1948-9366. PMC 5237817. PMID 28138363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Smyth, Luke; Bendinelli, Cino; Lee, Nicholas; Reeds, Matthew G.; Loh, Eu Jhin; Amico, Francesco; Balogh, Zsolt J.; Di Saverio, Salomone; Weber, Dieter; Ten Broek, Richard Peter; Abu-Zidan, Fikri M.; Campanelli, Giampiero; Beka, Solomon Gurmu; Chiarugi, Massimo; Shelat, Vishal G. (2022-03-04). "WSES guidelines on blunt and penetrating bowel injury: diagnosis, investigations, and treatment". World journal of emergency surgery: WJES. 17 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s13017-022-00418-y. ISSN 1749-7922. PMC 8896237. PMID 35246190.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bala, Miklosh; Kashuk, Jeffry; Moore, Ernest E.; Kluger, Yoram; Biffl, Walter; Gomes, Carlos Augusto; Ben-Ishay, Offir; Rubinstein, Chen; Balogh, Zsolt J.; Civil, Ian; Coccolini, Federico; Leppaniemi, Ari; Peitzman, Andrew; Ansaloni, Luca; Sugrue, Michael; Sartelli, Massimo; Di Saverio, Salomone; Fraga, Gustavo P.; Catena, Fausto (December 2017). "Acute mesenteric ischemia: guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery". World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 12 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s13017-017-0150-5. PMID 28794797.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)