Bruce Beutler: Difference between revisions

m task, replaced: Science (New York, N.Y.) → Science (7) |

m siccing |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

=== Discovery of the LPS receptor, and the role of TLRs in innate immune sensing === |

=== Discovery of the LPS receptor, and the role of TLRs in innate immune sensing === |

||

From the mid-1980s onward Beutler was interested in the mechanism by which LPS activates mammalian immune cells (chiefly [[macrophage]]s,<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4" /> but [[dendritic cell]]s and [[B cell]]s as well), sometimes leading to uncontrollable Gram negative septic shock,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Beutler |first=B. |last2=Poltorak |first2=A. |date=July 2001 |title=Sepsis and evolution of the innate immune response |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11445725 |journal=Critical Care Medicine |volume=29 |issue=7 Suppl |pages=S2–6; discussion S6–7 |doi=10.1097/00003246-200107001-00002 |issn=0090-3493 |pmid=11445725}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Beutler |first=Bruce |title=Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Septic Shock |publisher=Alan R. Liss, Inc. |year=1988 |editor-last=Roth |editor-first=B. |location=New York |pages=219–235 |chapter=Orchestration of septic shock by cytokines: the role of cachectin (tumor necrosis factor)}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Beutler |first=Bruce |title=Mediators of Sepsis |publisher=Springer Berlin |year=1992 |veditors=Lamy M, Thijs LG |location=Heidelberg |pages=51–67 |chapter=Cytokines in Shock: 1992}}</ref> but also promoting the well-known adjuvant effect of LPS,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Johnson |first=A. G. |last2=Gaines |first2=S. |last3=Landy |first3=M. |date=1956-02-01 |title=Studies on the O antigen of Salmonella typhosa. V. Enhancement of antibody response to protein antigens by the purified lipopolysaccharide |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13286429 |journal=The Journal of Experimental Medicine |volume=103 |issue=2 |pages=225–246 |doi=10.1084/jem.103.2.225 |issn=0022-1007 |pmc=2136584 |pmid=13286429}}</ref> and B cell mitogenesis<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Coutinho |first=A. |last2=Meo |first2=T. |date=December 1978 |title=Genetic basis for unresponsiveness to lipopolysaccharide in C57BL/10Cr mice |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21302052 |journal=Immunogenetics |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=17–24 |doi=10.1007/BF01843983 |issn=0093-7711 |pmid=21302052}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Watson |first=J. |last2=Riblet |first2=R. |date=1974-11-01 |title=Genetic control of responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharides in mice. I. Evidence for a single gene that influences mitogenic and immunogenic respones to lipopolysaccharides |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4138849 |journal=The Journal of Experimental Medicine |volume=140 |issue=5 |pages=1147–1161 |doi=10.1084/jem.140.5.1147 |issn=0022-1007 |pmc=2139714 |pmid=4138849}}</ref> and antibody production. A single, highly specific LPS receptor was presumed to exist as early as the 1960s, based on the fact that allelic mutations in two separate strains of mice, affecting a discrete genetic locus on chromosome 4 termed ''Lps'', abolished LPS sensing.<ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sultzer |first=B. M. |date=1968-09-21 |title=Genetic control of leucocyte responses to endotoxin |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4877918 |journal=Nature |volume=219 |issue=5160 |pages=1253–1254 |doi=10.1038/2191253a0 |issn=0028-0836 |pmid=4877918}}</ref> Although this receptor had been widely pursued, it remained elusive. Beutler reasoned that in finding the LPS receptor, insight might be gained into the first molecular events that transpire upon an encounter between the host and microbial invaders.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Beutler |first=Bruce |date=January 2002 |title=Toll-like receptors: how they work and what they do |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11753071 |journal=Current Opinion in Hematology |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=2–10 |doi=10.1097/00062752-200201000-00002 |issn=1065-6251 |pmid=11753071}}</ref> |

From the mid-1980s onward Beutler was interested in the mechanism by which LPS activates mammalian immune cells (chiefly [[macrophage]]s,<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4" /> but [[dendritic cell]]s and [[B cell]]s as well), sometimes leading to uncontrollable Gram negative septic shock,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Beutler |first=B. |last2=Poltorak |first2=A. |date=July 2001 |title=Sepsis and evolution of the innate immune response |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11445725 |journal=Critical Care Medicine |volume=29 |issue=7 Suppl |pages=S2–6; discussion S6–7 |doi=10.1097/00003246-200107001-00002 |issn=0090-3493 |pmid=11445725}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Beutler |first=Bruce |title=Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Septic Shock |publisher=Alan R. Liss, Inc. |year=1988 |editor-last=Roth |editor-first=B. |location=New York |pages=219–235 |chapter=Orchestration of septic shock by cytokines: the role of cachectin (tumor necrosis factor)}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Beutler |first=Bruce |title=Mediators of Sepsis |publisher=Springer Berlin |year=1992 |veditors=Lamy M, Thijs LG |location=Heidelberg |pages=51–67 |chapter=Cytokines in Shock: 1992}}</ref> but also promoting the well-known adjuvant effect of LPS,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Johnson |first=A. G. |last2=Gaines |first2=S. |last3=Landy |first3=M. |date=1956-02-01 |title=Studies on the O antigen of Salmonella typhosa. V. Enhancement of antibody response to protein antigens by the purified lipopolysaccharide |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13286429 |journal=The Journal of Experimental Medicine |volume=103 |issue=2 |pages=225–246 |doi=10.1084/jem.103.2.225 |issn=0022-1007 |pmc=2136584 |pmid=13286429}}</ref> and B cell mitogenesis<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Coutinho |first=A. |last2=Meo |first2=T. |date=December 1978 |title=Genetic basis for unresponsiveness to lipopolysaccharide in C57BL/10Cr mice |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21302052 |journal=Immunogenetics |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=17–24 |doi=10.1007/BF01843983 |issn=0093-7711 |pmid=21302052}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Watson |first=J. |last2=Riblet |first2=R. |date=1974-11-01 |title=Genetic control of responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharides in mice. I. Evidence for a single gene that influences mitogenic and immunogenic {{sic|nolink=y|reason=error in source|respones}} to lipopolysaccharides |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4138849 |journal=The Journal of Experimental Medicine |volume=140 |issue=5 |pages=1147–1161 |doi=10.1084/jem.140.5.1147 |issn=0022-1007 |pmc=2139714 |pmid=4138849}}</ref> and antibody production. A single, highly specific LPS receptor was presumed to exist as early as the 1960s, based on the fact that allelic mutations in two separate strains of mice, affecting a discrete genetic locus on chromosome 4 termed ''Lps'', abolished LPS sensing.<ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sultzer |first=B. M. |date=1968-09-21 |title=Genetic control of leucocyte responses to endotoxin |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4877918 |journal=Nature |volume=219 |issue=5160 |pages=1253–1254 |doi=10.1038/2191253a0 |issn=0028-0836 |pmid=4877918}}</ref> Although this receptor had been widely pursued, it remained elusive. Beutler reasoned that in finding the LPS receptor, insight might be gained into the first molecular events that transpire upon an encounter between the host and microbial invaders.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Beutler |first=Bruce |date=January 2002 |title=Toll-like receptors: how they work and what they do |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11753071 |journal=Current Opinion in Hematology |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=2–10 |doi=10.1097/00062752-200201000-00002 |issn=1065-6251 |pmid=11753071}}</ref> |

||

Utilizing [[positional cloning]] in an effort that began in 1993 and lasted five years, Beutler, together with several postdoctoral associates including Alexander Poltorak, measured TNF production as a qualitative phenotypic endpoint of the LPS response. Analyzing more than 2,000 [[Meiosis|meioses]], they confined the LPS receptor-encoding gene to a region of the genome encompassing approximately 5.8 million base pairs of [[DNA]].<ref name=":1" /> Sequencing most of the interval, they identified a gene within which each of two LPS-refractory strains of mice (C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr) had deleterious mutations. The gene, ''Tlr4'', encoded a cell surface protein with cytoplasmic domain homology to the [[interleukin-1 receptor]], and several other homologous genes that were scattered across the mouse genome. Beutler and his team thus proved that one of the mammalian Toll-like receptors, TLR4, acts as the membrane-spanning component of the mammalian LPS receptor complex.<ref name=":1" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Du |first=X. |last2=Poltorak |first2=A. |last3=Silva |first3=M. |last4=Beutler |first4=B. |date=1999 |title=Analysis of Tlr4-mediated LPS signal transduction in macrophages by mutational modification of the receptor |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10660480 |journal=Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases |volume=25 |issue=5-6 |pages=328–338 |doi=10.1006/bcmd.1999.0262 |issn=1079-9796 |pmid=10660480}}</ref><ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Poltorak |first=A. |last2=Ricciardi-Castagnoli |first2=P. |last3=Citterio |first3=S. |last4=Beutler |first4=B. |date=2000-02-29 |title=Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10681462 |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=97 |issue=5 |pages=2163–2167 |doi=10.1073/pnas.040565397 |issn=0027-8424 |pmc=15771 |pmid=10681462}}</ref> They also showed that while mouse TLR4 is activated by a tetra-acylated LPS-like molecule (lipid IVa), human TLR4 is not, recapitulating the species specificity for LPS partial structures.<ref name=":7" /> It was deduced that direct contact between TLR4 and LPS is a prerequisite for cell activation.<ref name=":7" /> Later, an extracellular component of the LPS receptor complex, MD-2 (also known as lymphocyte antigen 96), was identified by R. Shimazu and colleagues.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Shimazu |first=R. |last2=Akashi |first2=S. |last3=Ogata |first3=H. |last4=Nagai |first4=Y. |last5=Fukudome |first5=K. |last6=Miyake |first6=K. |last7=Kimoto |first7=M. |date=1999-06-07 |title=MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10359581 |journal=The Journal of Experimental Medicine |volume=189 |issue=11 |pages=1777–1782 |doi=10.1084/jem.189.11.1777 |issn=0022-1007 |pmc=2193086 |pmid=10359581}}</ref> The structure of the complex, with and without LPS bound, was solved by Jie-Oh Lee and colleagues in 2009.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Park |first=Beom Seok |last2=Song |first2=Dong Hyun |last3=Kim |first3=Ho Min |last4=Choi |first4=Byong-Seok |last5=Lee |first5=Hayyoung |last6=Lee |first6=Jie-Oh |date=2009-04-30 |title=The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19252480 |journal=Nature |volume=458 |issue=7242 |pages=1191–1195 |doi=10.1038/nature07830 |issn=1476-4687 |pmid=19252480}}</ref> |

Utilizing [[positional cloning]] in an effort that began in 1993 and lasted five years, Beutler, together with several postdoctoral associates including Alexander Poltorak, measured TNF production as a qualitative phenotypic endpoint of the LPS response. Analyzing more than 2,000 [[Meiosis|meioses]], they confined the LPS receptor-encoding gene to a region of the genome encompassing approximately 5.8 million base pairs of [[DNA]].<ref name=":1" /> Sequencing most of the interval, they identified a gene within which each of two LPS-refractory strains of mice (C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr) had deleterious mutations. The gene, ''Tlr4'', encoded a cell surface protein with cytoplasmic domain homology to the [[interleukin-1 receptor]], and several other homologous genes that were scattered across the mouse genome. Beutler and his team thus proved that one of the mammalian Toll-like receptors, TLR4, acts as the membrane-spanning component of the mammalian LPS receptor complex.<ref name=":1" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Du |first=X. |last2=Poltorak |first2=A. |last3=Silva |first3=M. |last4=Beutler |first4=B. |date=1999 |title=Analysis of Tlr4-mediated LPS signal transduction in macrophages by mutational modification of the receptor |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10660480 |journal=Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases |volume=25 |issue=5-6 |pages=328–338 |doi=10.1006/bcmd.1999.0262 |issn=1079-9796 |pmid=10660480}}</ref><ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Poltorak |first=A. |last2=Ricciardi-Castagnoli |first2=P. |last3=Citterio |first3=S. |last4=Beutler |first4=B. |date=2000-02-29 |title=Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10681462 |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=97 |issue=5 |pages=2163–2167 |doi=10.1073/pnas.040565397 |issn=0027-8424 |pmc=15771 |pmid=10681462}}</ref> They also showed that while mouse TLR4 is activated by a tetra-acylated LPS-like molecule (lipid IVa), human TLR4 is not, recapitulating the species specificity for LPS partial structures.<ref name=":7" /> It was deduced that direct contact between TLR4 and LPS is a prerequisite for cell activation.<ref name=":7" /> Later, an extracellular component of the LPS receptor complex, MD-2 (also known as lymphocyte antigen 96), was identified by R. Shimazu and colleagues.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Shimazu |first=R. |last2=Akashi |first2=S. |last3=Ogata |first3=H. |last4=Nagai |first4=Y. |last5=Fukudome |first5=K. |last6=Miyake |first6=K. |last7=Kimoto |first7=M. |date=1999-06-07 |title=MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10359581 |journal=The Journal of Experimental Medicine |volume=189 |issue=11 |pages=1777–1782 |doi=10.1084/jem.189.11.1777 |issn=0022-1007 |pmc=2193086 |pmid=10359581}}</ref> The structure of the complex, with and without LPS bound, was solved by Jie-Oh Lee and colleagues in 2009.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Park |first=Beom Seok |last2=Song |first2=Dong Hyun |last3=Kim |first3=Ho Min |last4=Choi |first4=Byong-Seok |last5=Lee |first5=Hayyoung |last6=Lee |first6=Jie-Oh |date=2009-04-30 |title=The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19252480 |journal=Nature |volume=458 |issue=7242 |pages=1191–1195 |doi=10.1038/nature07830 |issn=1476-4687 |pmid=19252480}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:32, 14 March 2023

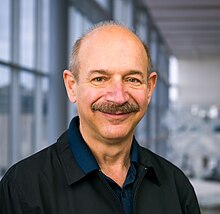

Bruce Beutler | |

|---|---|

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 2021 Photograph by Brian Coats | |

| Born | December 29, 1957 |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago, University of California, San Diego |

| Spouse(s) | Barbara Lanzl (c. 1980-1988; divorced; 3 children) |

| Awards | 2011 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Immunology |

| Institutions | University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center |

Bruce Alan Beutler (/ˈbɔɪtlər/ BOYT-lər; born December 29, 1957) is an American immunologist and geneticist. Together with Jules A. Hoffmann, he received one-half of the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for "discoveries concerning the activation of innate immunity."[1] Beutler discovered the long-elusive receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS; also known as endotoxin). He did so by identifying spontaneous mutations in the gene coding for mouse Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) in two unrelated strains of LPS-refractory mice and proving they were responsible for that phenotype.[2] Subsequently, and chiefly through the work of Shizuo Akira, other TLRs were shown to detect signature molecules of most infectious microbes, in each case triggering an innate immune response.[3][4][5][6][7]

The other half of the Nobel Prize went to Ralph M. Steinman for "his discovery of the dendritic cell and its role in adaptive immunity."[1]

Beutler is currently a Regental Professor and Director of the Center for the Genetics of Host Defense at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas.[8][9]

Early life and education

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Beutler lived in Southern California between the ages of 2 and 18 (1959 to 1977). For most of this time, he lived in city of Arcadia, a northeastern suburb of Los Angeles in the San Gabriel Valley. During these years, he spent much time hiking in the San Gabriel Mountains, and in regional national parks (Sequoia, Yosemite, Joshua Tree, and Grand Canyon), and was particularly fascinated by living things.[10] These experiences impelled an intense interest in biological science. His introduction to experimental biology, acquired between the ages of 14 and 18, included work in the laboratory of his father, Ernest Beutler, then at the City of Hope Medical Center in Duarte, CA. There he learned to assay enzymes of red blood cells and became familiar with methods for protein isolation. He published his studies of an electrophoretic variant of glutathione peroxidase,[11] as well as the inherent catalytic activity of inorganic selenite,[12] at the age of 17.

Beutler also worked in the City of Hope laboratory of Susumu Ohno, a geneticist known for his studies of evolution, genome structure, and sex differentiation in mammals. Ohno hypothesized that the major histocompatibility complex proteins served as anchorage sites for organogenesis-directing proteins.[13] He further suggested that H-Y antigen, a minor histocompatibility protein encoded by a gene on the Y chromosome and absent in female mammals, was responsible for directing organogenesis of the indifferent gonad to form a testis. In studying H-Y antigen,[14] Beutler became conversant with immunology and mouse genetics during the 1970s. While a college student at the University of California at San Diego, Beutler worked in the laboratory of Dan Lindsley, a Drosophila geneticist interested in spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis in the fruit fly. There, he learned to map phenotypes to chromosomal regions using visible phenotypic markers.[10] He also worked in the laboratory of Abraham Braude, an expert in the biology of LPS.

Beutler received his secondary school education at Polytechnic School in Pasadena, California. A precocious student, he graduated from high school at the age of 16, enrolled in college at the University of California, San Diego, and graduated with a BA degree at the age of 18 in 1976. He then enrolled in medical school at the University of Chicago in 1977 and received his M.D. degree in 1981 at the age of 23.[15] From 1981 to 1983 Beutler continued his medical training at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, as an intern in the Department of Internal Medicine, and as a resident in the Department of Neurology. However, he found clinical medicine less interesting than laboratory science, and decided to return to the laboratory.

Scientific contributions

Isolation of tumor necrosis factor and discovery of its inflammation-promoting effect

Beutler’s focus on innate immunity began when he was a postdoctoral associate and later an assistant professor in the lab of Anthony Cerami at Rockefeller University (1983-1986). Drawing upon skills he had acquired earlier, he isolated mouse “cachectin” from the conditioned medium of LPS-activated mouse macrophages. Cachectin was hypothesized by Cerami to be a mediator of wasting in chronic disease. Its biological activity, the suppression of lipoprotein lipase synthesis in adipocytes, was thought to contribute to wasting, since lipoprotein lipase cleaves fatty acids from circulating triglycerides, allowing their uptake and re-esterification within fat cells.[16] By sequential fractionation of LPS-activated macrophage medium, measuring cachectin activity at each step, Beutler purified cachectin to homogeneity.[17] Determining its N-terminal sequence, he recognized it as mouse tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and showed that it had strong TNF activity; moreover that human TNF, isolated by a very different assay, had strong cachectin activity.[16]

Human TNF, isolated contemporaneously by other workers,[18] had to that time been defined only by its ability to kill cancer cells. The discovery of a separate role for TNF as a catabolic switch was of considerable interest. Of still greater importance, Beutler demonstrated that TNF acted as a key mediator of endotoxin-induced shock.[19] This he accomplished by raising an antibody against mouse TNF, which he used to neutralize TNF in living mice challenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS).[19] The often-lethal systemic inflammatory response to LPS was significantly mitigated by passive immunization against TNF. The discovery that TNF caused an acute systemic inflammatory disease (LPS-induced shock) presaged its causative role in numerous chronic inflammatory diseases. With J.-M. Dayer, Beutler demonstrated that purified TNF could cause inflammation-associated responses in cultured human synoviocytes: secretion of collagenase and prostaglandin E2.[20] This was an early hint that TNF might be causally important in rheumatoid arthritis (as later shown by Feldmann, Brennan, and Maini[21]). Beutler also demonstrated the existence of TNF receptors on most cell types,[17] and correctly inferred the presence of two types of TNF receptor distinguished by their affinities, later cloned and designated p55 and p75 TNF receptors to denote their approximate molecular weights.[22][23][24][25][26] Before a sensitive immunoassay for TNF was feasible, Beutler used these receptors in a binding competition assay using radio-iodinated TNF as a tracer, which allowed him to precisely measure TNF in biological fluids.[27]

Invention of TNF inhibitors

Beutler was recruited to a faculty position at UT Southwestern Medical Center and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in 1986. Aware that TNF blockade might have clinical applications, he (along with a graduate student, David Crawford, and a postdoctoral associate, Karsten Peppel) invented and patented recombinant molecules expressly designed to neutralize TNF in vivo (Patent No. US5447851B1).[28] Fusing the binding portion of TNF receptor proteins to the heavy chain of an immunoglobulin molecule to force receptor dimerization,[28] they produced chimeric reagents with surprisingly high affinity and specificity for both TNF and a closely related cytokine called lymphotoxin, low antigenicity, and excellent stability in vivo. The human p75 receptor chimeric protein was later used extensively as the drug Etanercept in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, psoriasis, and other forms of inflammation. Marketed by Amgen, Etanercept achieved more than $74B in sales.[29]

Discovery of the LPS receptor, and the role of TLRs in innate immune sensing

From the mid-1980s onward Beutler was interested in the mechanism by which LPS activates mammalian immune cells (chiefly macrophages,[16][19] but dendritic cells and B cells as well), sometimes leading to uncontrollable Gram negative septic shock,[30][31][32] but also promoting the well-known adjuvant effect of LPS,[33] and B cell mitogenesis[34][35] and antibody production. A single, highly specific LPS receptor was presumed to exist as early as the 1960s, based on the fact that allelic mutations in two separate strains of mice, affecting a discrete genetic locus on chromosome 4 termed Lps, abolished LPS sensing.[34][36] Although this receptor had been widely pursued, it remained elusive. Beutler reasoned that in finding the LPS receptor, insight might be gained into the first molecular events that transpire upon an encounter between the host and microbial invaders.[37]

Utilizing positional cloning in an effort that began in 1993 and lasted five years, Beutler, together with several postdoctoral associates including Alexander Poltorak, measured TNF production as a qualitative phenotypic endpoint of the LPS response. Analyzing more than 2,000 meioses, they confined the LPS receptor-encoding gene to a region of the genome encompassing approximately 5.8 million base pairs of DNA.[2] Sequencing most of the interval, they identified a gene within which each of two LPS-refractory strains of mice (C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr) had deleterious mutations. The gene, Tlr4, encoded a cell surface protein with cytoplasmic domain homology to the interleukin-1 receptor, and several other homologous genes that were scattered across the mouse genome. Beutler and his team thus proved that one of the mammalian Toll-like receptors, TLR4, acts as the membrane-spanning component of the mammalian LPS receptor complex.[2][38][39] They also showed that while mouse TLR4 is activated by a tetra-acylated LPS-like molecule (lipid IVa), human TLR4 is not, recapitulating the species specificity for LPS partial structures.[39] It was deduced that direct contact between TLR4 and LPS is a prerequisite for cell activation.[39] Later, an extracellular component of the LPS receptor complex, MD-2 (also known as lymphocyte antigen 96), was identified by R. Shimazu and colleagues.[40] The structure of the complex, with and without LPS bound, was solved by Jie-Oh Lee and colleagues in 2009.[41]

Jules Hoffmann and colleagues had earlier shown that the Drosophila Toll protein, originally known for its role in embryogenesis, was essential for the antimicrobial peptide response to fungal infection.[42] However, no molecule derived from fungi actually became bound to Toll; rather, a proteolytic cascade led to the activation of an endogenous ligand, the protein Spätzle. This activated NF-kB within cells of the fat body, leading to antimicrobial peptide secretion.

Aware of this work, Charles Janeway and Ruslan Medzhitov overexpressed a modified version of human TLR4 (which they called ‘h-Toll’) and found it capable of activating the transcription factor NF-κB in mammalian cells.[43] They speculated that TLR4 was a “pattern recognition receptor.” However, they provided no evidence that TLR4 recognized any molecule of microbial origin. If a ligand did exist, it might have been endogenous (as in the fruit fly, where Toll recognizes the endogenous protein Spätzle, or as in the case of the IL-1 receptor, which recognizes the endogenous cytokine IL-1). Indeed, numerous cell surface receptors, including the TGFβ receptor, B cell receptor, and T cell receptor activate NF-κB. In short, it was not clear what TLR4 recognized, nor what it did. Separate publications, also based on transfection/overexpression studies, held that TLR2 rather than TLR4 was the LPS receptor.[44][45]

The genetic evidence of Beutler and coworkers correctly identified TLR4 as the specific and non-redundant cell surface receptor for LPS, fully required for virtually all LPS activities. This suggested that other TLRs (of which ten are now known to exist in humans) might also act as sensors of infection in mammals,[46] each detecting other signature molecules made by microbes whether or not they were pathogens in the classical sense of the term. The other TLRs, like TLR4, do indeed initiate innate immune responses. By promoting inflammatory signaling, TLRs can also mediate pathologic effects including fever, systemic inflammation, and shock. Sterile inflammatory and autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus also elicit TLR signaling, and disruption of signaling from the nucleic acid sensing TLRs can favorably modify the disease phenotype.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

Random Germline Mutagenesis/Forward Genetics in the mouse

After completing the positional cloning of the Lps locus in 1998, Beutler continued to apply a forward genetic approach to the analysis of immunity in mammals. In this process, germline mutations that alter immune function are created in mice through a random process using the alkylating agent ENU, detected by their phenotypic effects, and then isolated by positional cloning.[55] This work disclosed numerous essential signaling molecules required for the innate immune response,[56][57][58][59][60][61][62] and helped to delineate the biochemistry of innate immunity. Among the genes detected was Ticam1, implicated by an ENU-induced phenotype called Lps2.[56] The encoded protein TICAM1, also known as TRIF, was a new adaptor molecule, binding to the cytoplasmic domains of both TLR3 and TLR4, and needed for signaling by each.

Another phenotype, called 3d to connote a “triple defect” in TLR signaling, affected a gene of unknown function called Unc93b1.[58] TLRs 3, 7, and 9 (nucleic acid sensing TLRs) failed to signal in homozygotes for the mutation. These TLRs were found to be endosomal, and physically interact with the UNC93B1 protein which transports them to the endosomal compartment.[63] Humans with mutations in UNC93B1, the human ortholog of the same gene, were subsequently found to be susceptible to recurrent Herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis, in which reactivation of latent virus occurs repeatedly in the trigeminal ganglion at the base of the midbrain, leading to cortical neuron death.[64]

Yet another protein needed to make the endosomal environment suitable for TLR signaling was SLC15A4, identified based on the phenotype feeble.[65] feeble was identified in a screen in which immunostimulatory DNA was administered to mice intravenously with measurement of the systemic type I interferon response. Failure of this response, which is dependent on TLR9 signaling from plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) was observed in homozygous mutants, and subsequently, failure of TLR7 (but not TLR3) signaling was observed as well. Because the feeble mutation suppressed SLE in mice,[50] the SLC15A4 protein has become a target of interest for drug development.[66]

In all, Beutler and colleagues detected 77 mutations in 36 genes in which ENU-induced mutations created defects of TLR signaling, detected due to faulty TNF and/or interferon responses. These genes encoded all TLRs kept under surveillance in screening, all of the four adapter proteins that signal from TLRs, kinases and other signaling proteins downstream, chaperones needed to escort TLRs to their destinations, proteins that promote the availability of TLR ligands, proteins involved in vesicle transport, and proteins involved in transcriptional responses to TLR signaling, or the post-translational processing of TNF and/or type I interferons (the proteins assayed in screening).

Beutler and colleagues also used ENU mutagenesis to study the global response to a defined infectious agent. They measured susceptibility to mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) and identified numerous genes that make a life-or-death difference during infection, terming this set of genes the MCMV "resistome".[67][68] These genes were grouped into "sensing," "signaling," "effector," "homeostatic," and "developmental" categories, some of which were wholly unexpected. In the homeostatic category, for example, Kir6.1 ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the smooth muscle of the coronary arteries serve an essential role in the maintenance of blood flow during MCMV infection, and mutations that damage these channels cause sudden death during infection.[69]

Other genetic screens in the Beutler laboratory were used to identify genes that mediate homeostatic adaptations of the intestinal epithelium following a cytotoxic insult;[70][71][72][73][74][75][76] prevent allergic responses,[77] diabetes,[78][79] or obesity;[80][81][82] support normal hematopoiesis;[83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92] and enable humoral and cellular immunity.[93][94][95][96] Some of these (beginning ~2015) were identified by a new process called automated meiotic mapping, which enabled greatly accelerated mutation identification compared to traditional genetic mapping (see below). In the course of their work, Beutler and his colleagues also discovered genes required for biological processes such as normal iron absorption,[97] hearing,[98] pigmentation,[99][100] metabolism,[80][82][101][102][103] and embryonic development.[104] Many human diseases were ultimately linked to variants in the corresponding human genes after initial identification in the mouse by the Beutler laboratory,[64][105][106][107] or by the laboratories of collaborating investigators.[108][109][110]

Invention of Automated Meiotic Mapping

Prior to 2013, despite the development of methods for massively parallel sequencing and their application in finding induced germline mutations,[111][112][113] positional cloning remained a slow process, limited by the need to genetically map mutations to chromosomal intervals to ascertain which induced mutation (among the average of approximately 60 changes in coding and splicing function induced per pedigree) was responsible for an observed phenotype. This required expansion of a mutant stock, outcrossing to a mapping strain, backcrossing, and genotypic and phenotypic analysis of F2 offspring. Moreover, when phenotypic screening was performed prior to positional cloning, only large effect size mutations (producing essentially qualitative phenotypes) were recoverable.

Beutler invented a means of instantly identifying ENU-induced mutations that cause phenotypes.[114] The process, called automated meiotic mapping (AMM), eliminates the need to breed mutant mice to a mapping strain as required in classical genetic mapping and flags causative mutations as soon as phenotypic assay data are collected. In a laboratory setting, it accelerates positional cloning approximately 200-fold, and permits ongoing measurement of genome saturation as mutagenesis progresses.[115] Not only qualitative phenotypes, but subtle quantitative phenotypes, are detectable and mapped to individual mutations; hence the sensitivity of forward genetics is dramatically increased. AMM depends on statistical computation to detect associations between mutations in either the homozygous or heterozygous state and deviant phenotypes.[114] In addition, machine learning software, trained on the outcome of many thousands of experiments in which putative causative mutations were re-created and re-assayed for phenotype, is used to assess data quality.[116] As of 2022, more than 260,000 ENU-induced non-synonymous coding or splice site mutations had been assayed for phenotypic effects, and more than 5,800 mutations in approximately 2,500 genes had been declared causative of phenotype(s). For certain screens, such as flow cytometry performed on the blood of germline mutant mice, more than 55% saturation of the genome has been achieved (i.e., more than 55% of all genes in which mutations will create flow cytometric aberrations in the peripheral blood have been detected, most of them based on assessment of multiple alleles, as of July 2021).[116]

AMM led to the discovery of many new immunodeficiency disorders,[86][87][88][89][90][91][92][83][96] and disorders of bone morphology or mineral density,[109][110] vision,[117] and metabolism.[80][82][102][103] Of note, AMM was used in the identification of a chemosensor that mediates innate fear behavior in mice and an autism gene found first in mice and then shown to cause autism in humans.[108][118] AMM has also permitted high speed searches for mutations that suppress or augment disease phenotypes; for example, the development of autoimmune (Type 1) diabetes in mice of the NOD strain.[78][79] It offers a rational way to investigate the pathogenesis of complex disease phenotypes in general, in which many loci invariably contribute to susceptibility or resistance to disease, and disease occurs in those individuals with an unfavorable imbalance between these opposing influences.

Developing drugs that activate TLRs

Beutler has collaborated with Dale L. Boger and his research group to identify synthetic small molecule agonists of mammalian TLRs, which may be used in combination with defined molecular antigens to precisely target and coordinate innate and adaptive immune responses.[119][120][121][122][123][124][125]

Awards and recognition

Awards

- 1993 - Alexander von Humboldt Fellow; Germany

- 1994 - Young Investigator Award (American Federation for Clinical Research); United States

- 2001 - “Highly Cited” Researcher, Institute for Scientific Information; United States

- 2004 - Robert Koch Prize (Robert Koch Stiftung); Germany (shared with Jules A. Hoffmann and Shizuo Akira)

- 2006 - William B. Coley Award (Cancer Research Institute); United States (shared with Shizuo Akira)

- 2006 - Gran Prix Charles-Léopold Mayer (Académie des Sciences); France

- 2007 - Recipient of NIH/NIGMS MERIT Award; United States

- 2007 - Balzan Prize (International Balzan Foundation); Italy and Switzerland (shared with Jules A. Hoffmann)

- 2008 - Frederik B. Bang Award (The Stanley Watson Foundation); United States

- 2008 - “Citation Laureate,” Thomson Reuters

- 2009 - Will Rogers Institute Annual Prize for Scientific Research; United States

- 2009 - Albany Medical Center Prize in Medicine and Biomedical Research; United States (shared with Charles A. Dinarello and Ralph M. Steinman)[126]

- 2010 - University of Chicago, Professional Achievement Citation; United States

- 2011 - Shaw Prize; China (shared with Jules A. Hoffmann and Ruslan M. Medzhitov)

- 2011 - Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine; Sweden (shared with Jules A. Hoffmann and Ralph M. Steinman)[1]

- 2012 - Drexel Medicine Prize in Immunology; United States

- 2013 - Rabbi Shai Shacknai Memorial Prize in Immunology and Cancer Research, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Israel

- 2013 - Distinguished Service Award, University of Chicago; United States

- 2013 - Korsmeyer Award; United States

- 2016 - UCSD Distinguished Alumnus Award; United States

Honorary Doctoral Degrees

- 2007 - Doctor Med. Honoris Causa, Technical University of Munich; Germany

- 2009 - Honorary Doctoral Degree, Xiamen University; China

- 2012 - Honorary Professor, Trinity College; Ireland

- 2013 - Honorary Professor, Peking University; China

- 2014 - Honorary Professor, Shanghai Jiao Tong University; China

- 2014 - Chair of the Beutler Institute Council, Xiamen University; China

- 2014 - Honorary Professor, Xiamen University; China

- 2015 - Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Chile; Chile

- 2015 - Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Marseille; France

- 2015 - Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Brasilia; Brazil

- 2015 - Doctor Honoris Causa,[127] Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU); Norway

- 2015 - Honorary Professor at Naresuan University; Thailand

- 2016 - Honorary Doctorate, University of Athens; Greece

- 2017 - Doctor Med. Honoris Causa, University of Ottawa; Canada

- 2017 - Honorary Professor, Tianjin University; China

- 2019 - Honorary Degree, Jewish Theological Seminary; United States

- 2019 - Laurea Magistrale honoris causa in Medicina e Chirurgia (LM41),[128] Universita Magna Grecia of Catanzaro; Italy

Honorary and Learned Societies

- 1990 - Elected Member, American Society for Clinical Investigation; United States

- 2001 - Elected Member, Association of American Physicians; United States

- 2008 - Elected Member, National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine); United States

- 2008 - Elected Member, National Academy of Sciences; United States

- 2009 - Elected Associate (Foreign) Member, European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO)

- 2012 - Officier de la Legion D’Honneur; France

- 2012 - Elected Member,[129] German National Academy of Sciences (Leopoldina); Germany

- 2013 - Elected Member, American Academy of Arts & Sciences; United States

- 2015 - Elected Member, Royal Academy of Medicine; Belgium

- 2015 - Elected Foreign Member, Academy of Athens; Greece

- 2016 - Corresponding Member, Class of Physical Sciences, Accademia delle Scienze; Italy

- 2018 - Elected Fellow of the AACR Academy; United States

Family

Bruce Beutler was the third son of Ernest Beutler (1928-2008) and Brondelle May Beutler (née Fleisher; 1928-2019). His siblings included two older brothers (Steven [b. 1951] and Earl [b. 1954]), and a younger sister, Deborah [b. 1962]). Ernest, Bruce, Steven and Deborah were all physicians while Earl, a software engineer and entrepreneur, worked together with Ernest to create bibliographic retrieval software for publishing scientists (see Reference Manager) as well as other software products.

Ernest Beutler was a hematologist and medical geneticist famed for his studies of G-6-PD deficiency,[130] other hemolytic anemias,[131][132] iron metabolism,[133] glycolipid storage diseases,[134] and leukemias,[135][136] as well as his discovery of X chromosome inactivation.[137] He was a Professor and department chairman at The Scripps Research Institute contemporaneously with Bruce. The two collaborated productively on several topics prior to Ernest Beutler’s death in 2008.[11][12][138][139][140][141]

Both of Ernest Beutler’s parents were physicians.[142] Bruce Beutler’s paternal grandmother, Kathe Beutler (née Italiener, daughter of Anna Rothstein, 1896-1999),[143] was a pediatrician, trained at the Charité hospital in Berlin, earning her medical diploma in 1923. Käthe Italiener married Alfred Beutler in 1925. Also a physician, Alfred Beutler was a cousin to the spectral physicist, Hans G. Beutler (1896-1942), who worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute and the University of Berlin before emigrating to the USA in 1936. He continued his work at the University of Chicago until his death.[144]

One of Käthe’s Beutler’s first cousins was Kurt Rosenthal (aka Curtis Ronald), a banker and grandfather of Pamela Ronald,[145] who discovered the first plant sensor of a molecule derived from a microbial pathogen. Known as XA21, this protein exhibits structural homology to TLR4 (shown by Beutler to be the LPS receptor). Notably, while both Beutler and Ronald were pioneers in the genetics of innate immunity, neither was aware of the other’s work and its possible relevance to their own prior to making their respective discoveries of mammalian and plant sensors of infection. Käthe Beutler, however, was aware that each was a scientist and a member of her extended family. She had informed each of the other’s existence, though she lacked detailed knowledge of their work.[145]

Bruce Beutler married Barbara Beutler (née Lanzl) in 1980 and divorced in 1988. Three sons were born to the couple: Daniel Beutler (born 1983), Elliot Beutler (born 1984), and Jonathan Beutler (born 1987). Elliot Beutler, a physicist, is currently a postdoctoral associate at University of Washington, Seattle. Coincidentally, his work is topically related to that of Hans G. Beutler, his first cousin, thrice removed. Jonathan Beutler, a plant biologist, is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2011" (Press release). Nobel Foundation. October 3, 2011.

- ^ a b c Poltorak, A.; He, X.; Smirnova, I.; Liu, M. Y.; Van Huffel, C.; Du, X.; Birdwell, D.; Alejos, E.; Silva, M.; Galanos, C.; Freudenberg, M.; Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P.; Layton, B.; Beutler, B. (December 11, 1998). "Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene". Science. 282 (5396): 2085–2088. doi:10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9851930.

- ^ Hemmi, Hiroaki; Kaisho, Tsuneyasu; Takeuchi, Osamu; Sato, Shintaro; Sanjo, Hideki; Hoshino, Katsuaki; Horiuchi, Takao; Tomizawa, Hideyuki; Takeda, Kiyoshi; Akira, Shizuo (January 22, 2002). "Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway". Nature Immunology. 3 (2): 196–200. doi:10.1038/ni758. ISSN 1529-2908. PMID 11812998.

- ^ Hemmi, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Kawai, T.; Kaisho, T.; Sato, S.; Sanjo, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Hoshino, K.; Wagner, H.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S. (December 7, 2000). "A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA". Nature. 408 (6813): 740–745. doi:10.1038/35047123. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11130078.

- ^ Takeuchi, O.; Hoshino, K.; Kawai, T.; Sanjo, H.; Takada, H.; Ogawa, T.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S. (October 1, 1999). "Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components". Immunity. 11 (4): 443–451. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80119-3. ISSN 1074-7613. PMID 10549626.

- ^ Takeuchi, O.; Kawai, T.; Mühlradt, P. F.; Morr, M.; Radolf, J. D.; Zychlinsky, A.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S. (July 1, 2001). "Discrimination of bacterial lipoproteins by Toll-like receptor 6". International Immunology. 13 (7): 933–940. doi:10.1093/intimm/13.7.933. ISSN 0953-8178. PMID 11431423.

- ^ Takeuchi, Osamu; Sato, Shintaro; Horiuchi, Takao; Hoshino, Katsuaki; Takeda, Kiyoshi; Dong, Zhongyun; Modlin, Robert L.; Akira, Shizuo (July 1, 2002). "Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins". Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950). 169 (1): 10–14. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.10. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 12077222.

- ^ Ravindran, S. (2013). "Profile of Bruce A. Beutler". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (32): 12857–8. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11012857R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1311624110. PMC 3740904. PMID 23858464.

- ^ "Center for the Genetics of Host Defense - UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX". Retrieved March 9, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Bruce A. Beutler - Biographical - NobelPrize.org". Retrieved March 9, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Beutler, E.; West, C.; Beutler, B. (October 1974). "Electrophoretic polymorphism of glutathione peroxidase". Annals of Human Genetics. 38 (2): 163–169. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.1974.tb01947.x. ISSN 0003-4800. PMID 4467780.

- ^ a b Beutler, E.; Beutler, B.; Matsumoto, J. (July 15, 1975). "Glutathione peroxidase activity of inorganic selenium and seleno-DL-cysteine". Experientia. 31 (7): 769–770. doi:10.1007/BF01938453. ISSN 0014-4754. PMID 1140308.

- ^ Ohno, S. (January 1977). "The original function of MHC antigens as the general plasma membrane anchorage site of organogenesis-directing proteins". Immunological Reviews. 33: 59–69. ISSN 0105-2896. PMID 66186.

- ^ Beutler, B.; Nagai, Y.; Ohno, S.; Klein, G.; Shapiro, I. M. (March 1978). "The HLA-dependent expression of testis- organizing H-Y antigen by human male cells". Cell. 13 (3): 509–513. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(78)90324-0. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 77737.

- ^ Easton, John (October 10, 2011). "Alumnus Bruce Beutler, MD'81, to receive 2011 Nobel Prize in Medicine". uchicago news. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Beutler, B.; Greenwald, D.; Hulmes, J. D.; Chang, M.; Pan, Y. C.; Mathison, J.; Ulevitch, R.; Cerami, A. (August 1, 1985). "Identity of tumour necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin". Nature. 316 (6028): 552–554. doi:10.1038/316552a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 2993897.

- ^ a b Beutler, B.; Mahoney, J.; Le Trang, N.; Pekala, P.; Cerami, A. (May 1, 1985). "Purification of cachectin, a lipoprotein lipase-suppressing hormone secreted by endotoxin-induced RAW 264.7 cells". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 161 (5): 984–995. doi:10.1084/jem.161.5.984. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2187615. PMID 3872925.

- ^ Aggarwal, B. B.; Kohr, W. J.; Hass, P. E.; Moffat, B.; Spencer, S. A.; Henzel, W. J.; Bringman, T. S.; Nedwin, G. E.; Goeddel, D. V.; Harkins, R. N. (February 25, 1985). "Human tumor necrosis factor. Production, purification, and characterization". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 260 (4): 2345–2354. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 3871770.

- ^ a b c Beutler, B.; Milsark, I. W.; Cerami, A. C. (August 30, 1985). "Passive immunization against cachectin/tumor necrosis factor protects mice from lethal effect of endotoxin". Science. 229 (4716): 869–871. doi:10.1126/science.3895437. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 3895437.

- ^ Dayer, J. M.; Beutler, B.; Cerami, A. (December 1, 1985). "Cachectin/tumor necrosis factor stimulates collagenase and prostaglandin E2 production by human synovial cells and dermal fibroblasts". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 162 (6): 2163–2168. doi:10.1084/jem.162.6.2163. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2187983. PMID 2999289.

- ^ Feldmann, M.; Brennan, F. M.; Maini, R. N. (1996). "Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis". Annual Review of Immunology. 14: 397–440. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.397. ISSN 0732-0582. PMID 8717520.

- ^ Engelmann, H.; Novick, D.; Wallach, D. (January 25, 1990). "Two tumor necrosis factor-binding proteins purified from human urine. Evidence for immunological cross-reactivity with cell surface tumor necrosis factor receptors". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (3): 1531–1536. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 2153136.

- ^ Loetscher, H.; Pan, Y. C.; Lahm, H. W.; Gentz, R.; Brockhaus, M.; Tabuchi, H.; Lesslauer, W. (April 20, 1990). "Molecular cloning and expression of the human 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor". Cell. 61 (2): 351–359. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90815-v. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 2158862.

- ^ Nophar, Y.; Kemper, O.; Brakebusch, C.; Englemann, H.; Zwang, R.; Aderka, D.; Holtmann, H.; Wallach, D. (October 1, 1990). "Soluble forms of tumor necrosis factor receptors (TNF-Rs). The cDNA for the type I TNF-R, cloned using amino acid sequence data of its soluble form, encodes both the cell surface and a soluble form of the receptor". The EMBO journal. 9 (10): 3269–3278. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07526.x. ISSN 0261-4189. PMC 552060. PMID 1698610.

- ^ Schall, T. J.; Lewis, M.; Koller, K. J.; Lee, A.; Rice, G. C.; Wong, G. H.; Gatanaga, T.; Granger, G. A.; Lentz, R.; Raab, H. (April 20, 1990). "Molecular cloning and expression of a receptor for human tumor necrosis factor". Cell. 61 (2): 361–370. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90816-w. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 2158863.

- ^ Smith, C. A.; Davis, T.; Anderson, D.; Solam, L.; Beckmann, M. P.; Jerzy, R.; Dower, S. K.; Cosman, D.; Goodwin, R. G. (May 25, 1990). "A receptor for tumor necrosis factor defines an unusual family of cellular and viral proteins". Science. 248 (4958): 1019–1023. doi:10.1126/science.2160731. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 2160731.

- ^ Poltorak, A.; Peppel, K.; Beutler, B. (February 28, 1994). "Receptor-mediated label-transfer assay (RELAY): a novel method for the detection of plasma tumor necrosis factor at attomolar concentrations". Journal of Immunological Methods. 169 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(94)90128-7. ISSN 0022-1759. PMID 8133076.

- ^ a b Peppel, K.; Crawford, D.; Beutler, B. (December 1, 1991). "A tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-IgG heavy chain chimeric protein as a bivalent antagonist of TNF activity". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 174 (6): 1483–1489. doi:10.1084/jem.174.6.1483. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2119031. PMID 1660525.

- ^ Gardner, Jonathan (November 1, 2021). "A three-decade monopoly: how Amgen built a patent thicket around its top-selling drug | BioPharma Dive". BioPharma Dive. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ Beutler, B.; Poltorak, A. (July 2001). "Sepsis and evolution of the innate immune response". Critical Care Medicine. 29 (7 Suppl): S2–6, discussion S6–7. doi:10.1097/00003246-200107001-00002. ISSN 0090-3493. PMID 11445725.

- ^ Beutler, Bruce (1988). "Orchestration of septic shock by cytokines: the role of cachectin (tumor necrosis factor)". In Roth, B. (ed.). Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Septic Shock. New York: Alan R. Liss, Inc. pp. 219–235.

- ^ Beutler B (1992). "Cytokines in Shock: 1992". In Lamy M, Thijs LG (eds.). Mediators of Sepsis. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin. pp. 51–67.

- ^ Johnson, A. G.; Gaines, S.; Landy, M. (February 1, 1956). "Studies on the O antigen of Salmonella typhosa. V. Enhancement of antibody response to protein antigens by the purified lipopolysaccharide". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 103 (2): 225–246. doi:10.1084/jem.103.2.225. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2136584. PMID 13286429.

- ^ a b Coutinho, A.; Meo, T. (December 1978). "Genetic basis for unresponsiveness to lipopolysaccharide in C57BL/10Cr mice". Immunogenetics. 7 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1007/BF01843983. ISSN 0093-7711. PMID 21302052.

- ^ Watson, J.; Riblet, R. (November 1, 1974). "Genetic control of responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharides in mice. I. Evidence for a single gene that influences mitogenic and immunogenic respones [sic] to lipopolysaccharides". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 140 (5): 1147–1161. doi:10.1084/jem.140.5.1147. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2139714. PMID 4138849.

- ^ Sultzer, B. M. (September 21, 1968). "Genetic control of leucocyte responses to endotoxin". Nature. 219 (5160): 1253–1254. doi:10.1038/2191253a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 4877918.

- ^ Beutler, Bruce (January 2002). "Toll-like receptors: how they work and what they do". Current Opinion in Hematology. 9 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1097/00062752-200201000-00002. ISSN 1065-6251. PMID 11753071.

- ^ Du, X.; Poltorak, A.; Silva, M.; Beutler, B. (1999). "Analysis of Tlr4-mediated LPS signal transduction in macrophages by mutational modification of the receptor". Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases. 25 (5–6): 328–338. doi:10.1006/bcmd.1999.0262. ISSN 1079-9796. PMID 10660480.

- ^ a b c Poltorak, A.; Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P.; Citterio, S.; Beutler, B. (February 29, 2000). "Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (5): 2163–2167. doi:10.1073/pnas.040565397. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 15771. PMID 10681462.

- ^ Shimazu, R.; Akashi, S.; Ogata, H.; Nagai, Y.; Fukudome, K.; Miyake, K.; Kimoto, M. (June 7, 1999). "MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 189 (11): 1777–1782. doi:10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2193086. PMID 10359581.

- ^ Park, Beom Seok; Song, Dong Hyun; Kim, Ho Min; Choi, Byong-Seok; Lee, Hayyoung; Lee, Jie-Oh (April 30, 2009). "The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex". Nature. 458 (7242): 1191–1195. doi:10.1038/nature07830. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 19252480.

- ^ Lemaitre, B.; Nicolas, E.; Michaut, L.; Reichhart, J. M.; Hoffmann, J. A. (September 20, 1996). "The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults". Cell. 86 (6): 973–983. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 8808632.

- ^ Medzhitov, R.; Preston-Hurlburt, P.; Janeway, C. A. (July 24, 1997). "A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity". Nature. 388 (6640): 394–397. doi:10.1038/41131. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 9237759.

- ^ Kirschning, C. J.; Wesche, H.; Merrill Ayres, T.; Rothe, M. (December 7, 1998). "Human toll-like receptor 2 confers responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharide". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 188 (11): 2091–2097. doi:10.1084/jem.188.11.2091. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2212382. PMID 9841923.

- ^ Yang, R. B.; Mark, M. R.; Gray, A.; Huang, A.; Xie, M. H.; Zhang, M.; Goddard, A.; Wood, W. I.; Gurney, A. L.; Godowski, P. J. (September 17, 1998). "Toll-like receptor-2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular signalling". Nature. 395 (6699): 284–288. doi:10.1038/26239. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 9751057.

- ^ Beutler, B.; Poltorak, A. (June 2000). "Positional cloning of Lps, and the general role of toll-like receptors in the innate immune response". European Cytokine Network. 11 (2): 143–152. ISSN 1148-5493. PMID 10903793.

- ^ Christensen, Sean R.; Shupe, Jonathan; Nickerson, Kevin; Kashgarian, Michael; Flavell, Richard A.; Shlomchik, Mark J. (September 2006). "Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus". Immunity. 25 (3): 417–428. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013. ISSN 1074-7613. PMID 16973389.

- ^ Brown, Grant J.; Cañete, Pablo F.; Wang, Hao; Medhavy, Arti; Bones, Josiah; Roco, Jonathan A.; He, Yuke; Qin, Yuting; Cappello, Jean; Ellyard, Julia I.; Bassett, Katharine; Shen, Qian; Burgio, Gaetan; Zhang, Yaoyuan; Turnbull, Cynthia (May 2022). "TLR7 gain-of-function genetic variation causes human lupus". Nature. 605 (7909): 349–356. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04642-z. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9095492. PMID 35477763.

- ^ Leibler, Claire; John, Shinu; Elsner, Rebecca A.; Thomas, Kayla B.; Smita, Shuchi; Joachim, Stephen; Levack, Russell C.; Callahan, Derrick J.; Gordon, Rachael A.; Bastacky, Sheldon; Fukui, Ryutaro; Miyake, Kensuke; Gingras, Sebastien; Nickerson, Kevin M.; Shlomchik, Mark J. (October 2022). "Genetic dissection of TLR9 reveals complex regulatory and cryptic proinflammatory roles in mouse lupus". Nature Immunology. 23 (10): 1457–1469. doi:10.1038/s41590-022-01310-2. ISSN 1529-2916. PMC 9561083. PMID 36151396.

- ^ a b Baccala, Roberto; Gonzalez-Quintial, Rosana; Blasius, Amanda L.; Rimann, Ivo; Ozato, Keiko; Kono, Dwight H.; Beutler, Bruce; Theofilopoulos, Argyrios N. (February 19, 2013). "Essential requirement for IRF8 and SLC15A4 implicates plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of lupus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (8): 2940–2945. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222798110. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3581947. PMID 23382217.

- ^ Kono, Dwight H.; Haraldsson, M. Katarina; Lawson, Brian R.; Pollard, K. Michael; Koh, Yi Ting; Du, Xin; Arnold, Carrie N.; Baccala, Roberto; Silverman, Gregg J.; Beutler, Bruce A.; Theofilopoulos, Argyrios N. (July 21, 2009). "Endosomal TLR signaling is required for anti-nucleic acid and rheumatoid factor autoantibodies in lupus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (29): 12061–12066. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905441106. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2715524. PMID 19574451.

- ^ Lau, Christina M.; Broughton, Courtney; Tabor, Abigail S.; Akira, Shizuo; Flavell, Richard A.; Mamula, Mark J.; Christensen, Sean R.; Shlomchik, Mark J.; Viglianti, Gregory A.; Rifkin, Ian R.; Marshak-Rothstein, Ann (November 7, 2005). "RNA-associated autoantigens activate B cells by combined B cell antigen receptor/Toll-like receptor 7 engagement". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 202 (9): 1171–1177. doi:10.1084/jem.20050630. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2213226. PMID 16260486.

- ^ Leadbetter, Elizabeth A.; Rifkin, Ian R.; Hohlbaum, Andreas M.; Beaudette, Britte C.; Shlomchik, Mark J.; Marshak-Rothstein, Ann (April 11, 2002). "Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors". Nature. 416 (6881): 603–607. doi:10.1038/416603a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11948342.

- ^ Viglianti, Gregory A.; Lau, Christina M.; Hanley, Timothy M.; Miko, Benjamin A.; Shlomchik, Mark J.; Marshak-Rothstein, Ann (December 2003). "Activation of autoreactive B cells by CpG dsDNA". Immunity. 19 (6): 837–847. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00323-6. ISSN 1074-7613. PMID 14670301.

- ^ Beutler, Bruce; Du, Xin; Xia, Yu (July 2007). "Precis on forward genetics in mice". Nature Immunology. 8 (7): 659–664. doi:10.1038/ni0707-659. ISSN 1529-2908. PMID 17579639.

- ^ a b Hoebe, K.; Du, X.; Georgel, P.; Janssen, E.; Tabeta, K.; Kim, S. O.; Goode, J.; Lin, P.; Mann, N.; Mudd, S.; Crozat, K.; Sovath, S.; Han, J.; Beutler, B. (August 14, 2003). "Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling". Nature. 424 (6950): 743–748. doi:10.1038/nature01889. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 12872135.

- ^ Hoebe, Kasper; Georgel, Philippe; Rutschmann, Sophie; Du, Xin; Mudd, Suzanne; Crozat, Karine; Sovath, Sosathya; Shamel, Louis; Hartung, Thomas; Zähringer, Ulrich; Beutler, Bruce (February 3, 2005). "CD36 is a sensor of diacylglycerides". Nature. 433 (7025): 523–527. doi:10.1038/nature03253. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15690042.

- ^ a b Tabeta, Koichi; Hoebe, Kasper; Janssen, Edith M.; Du, Xin; Georgel, Philippe; Crozat, Karine; Mudd, Suzanne; Mann, Navjiwan; Sovath, Sosathya; Goode, Jason; Shamel, Louis; Herskovits, Anat A.; Portnoy, Daniel A.; Cooke, Michael; Tarantino, Lisa M. (January 15, 2006). "The Unc93b1 mutation 3d disrupts exogenous antigen presentation and signaling via Toll-like receptors 3, 7 and 9". Nature Immunology. 7 (2): 156–164. doi:10.1038/ni1297. ISSN 1529-2908. PMID 16415873.

- ^ Croker, Ben A.; Lawson, Brian R.; Rutschmann, Sophie; Berger, Michael; Eidenschenk, Celine; Blasius, Amanda L.; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Sovath, Sosathya; Cengia, Louise; Shultz, Leonard D.; Theofilopoulos, Argyrios N.; Pettersson, Sven; Beutler, Bruce Alan (September 30, 2008). "Inflammation and autoimmunity caused by a SHP1 mutation depend on IL-1, MyD88, and a microbial trigger". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (39): 15028–15033. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806619105. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2567487. PMID 18806225.

- ^ Shi, Hexin; Wang, Ying; Li, Xiaohong; Zhan, Xiaoming; Tang, Miao; Fina, Maggy; Su, Lijing; Pratt, David; Bu, Chun Hui; Hildebrand, Sara; Lyon, Stephen; Scott, Lindsay; Quan, Jiexia; Sun, Qihua; Russell, Jamie (December 7, 2015). "NLRP3 activation and mitosis are mutually exclusive events coordinated by NEK7, a new inflammasome component". Nature Immunology. 17 (3): 250–258. doi:10.1038/ni.3333. ISSN 1529-2916. PMC 4862588. PMID 26642356.

- ^ Sun, Lei; Jiang, Zhengfan; Acosta-Rodriguez, Victoria A.; Berger, Michael; Du, Xin; Choi, Jin Huk; Wang, Jianhui; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Kilaru, Gokhul K.; Mohawk, Jennifer A.; Quan, Jiexia; Scott, Lindsay; Hildebrand, Sara; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao (November 6, 2017). "HCFC2 is needed for IRF1- and IRF2-dependent Tlr3 transcription and for survival during viral infections". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 214 (11): 3263–3277. doi:10.1084/jem.20161630. ISSN 1540-9538. PMC 5679162. PMID 28970238.

- ^ Shi, Hexin; Sun, Lei; Wang, Ying; Liu, Aijie; Zhan, Xiaoming; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao; Anderton, Priscilla; Hildebrand, Sara; Quan, Jiexia; Ludwig, Sara; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Beutler, Bruce (March 2, 2021). "N4BP1 negatively regulates NF-κB by binding and inhibiting NEMO oligomerization". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 1379. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21711-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7925594. PMID 33654074.

- ^ Kim, You-Me; Brinkmann, Melanie M.; Paquet, Marie-Eve; Ploegh, Hidde L. (March 13, 2008). "UNC93B1 delivers nucleotide-sensing toll-like receptors to endolysosomes". Nature. 452 (7184): 234–238. doi:10.1038/nature06726. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 18305481.

- ^ a b Casrouge, Armanda; Zhang, Shen-Ying; Eidenschenk, Céline; Jouanguy, Emmanuelle; Puel, Anne; Yang, Kun; Alcais, Alexandre; Picard, Capucine; Mahfoufi, Nora; Nicolas, Nathalie; Lorenzo, Lazaro; Plancoulaine, Sabine; Sénéchal, Brigitte; Geissmann, Frédéric; Tabeta, Koichi (October 13, 2006). "Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in human UNC-93B deficiency". Science. 314 (5797): 308–312. doi:10.1126/science.1128346. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 16973841.

- ^ Blasius, Amanda L.; Arnold, Carrie N.; Georgel, Philippe; Rutschmann, Sophie; Xia, Yu; Lin, Pei; Ross, Charles; Li, Xiaohong; Smart, Nora G.; Beutler, Bruce (November 16, 2010). "Slc15a4, AP-3, and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome proteins are required for Toll-like receptor signaling in plasmacytoid dendritic cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (46): 19973–19978. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014051107. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2993408. PMID 21045126.

- ^ Lazar, Daniel C.; Wang, Wesley W.; Chiu, Tzu-Yuan; Li, Weichao; Jadhav, Appaso M.; Wozniak, Jacob M.; Gazaniga, Nathalia; Theofilopoulos, Argyrios N.; Teijaro, John R.; Parker, Christopher G. (October 7, 2022). "Chemoproteomics-guided development of SLC15A4 inhibitors with anti-inflammatory activity". doi:10.1101/2022.10.07.511216.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Beutler, Bruce; Crozat, Karine; Koziol, James A.; Georgel, Philippe (February 2005). "Genetic dissection of innate immunity to infection: the mouse cytomegalovirus model". Current Opinion in Immunology. 17 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2004.11.004. ISSN 0952-7915. PMID 15653308.

- ^ Beutler, Bruce; Eidenschenk, Celine; Crozat, Karine; Imler, Jean-Luc; Takeuchi, Osamu; Hoffmann, Jules A.; Akira, Shizuo (October 2007). "Genetic analysis of resistance to viral infection". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 7 (10): 753–766. doi:10.1038/nri2174. ISSN 1474-1741. PMID 17893693.

- ^ Croker, B.; Crozat, K.; Berger, M.; Xia, Y.; Sovath, S.; Schaffer, L.; Eleftherianos, I.; Imler, J. L.; Beutler, B. (2007). "ATP-sensitive potassium channels mediate survival during infection in mammals and insects". Nature Genetics. 39 (12): 1453–1460. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.25. PMID 18026101. S2CID 41183715.

- ^ Brandl, Katharina; Rutschmann, Sophie; Li, Xiaohong; Du, Xin; Xiao, Nengming; Schnabl, Bernd; Brenner, David A.; Beutler, Bruce (March 3, 2009). "Enhanced sensitivity to DSS colitis caused by a hypomorphic Mbtps1 mutation disrupting the ATF6-driven unfolded protein response". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (9): 3300–3305. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813036106. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2651297. PMID 19202076.

- ^ Brandl, Katharina; Sun, Lei; Neppl, Christina; Siggs, Owen M.; Le Gall, Sylvain M.; Tomisato, Wataru; Li, Xiaohong; Du, Xin; Maennel, Daniela N.; Blobel, Carl P.; Beutler, Bruce (November 16, 2010). "MyD88 signaling in nonhematopoietic cells protects mice against induced colitis by regulating specific EGF receptor ligands". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (46): 19967–19972. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014669107. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2993336. PMID 21041656.

- ^ Brandl, Katharina; Tomisato, Wataru; Li, Xiaohong; Neppl, Christina; Pirie, Elaine; Falk, Werner; Xia, Yu; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Baccala, Roberto; Theofilopoulos, Argyrios N.; Schnabl, Bernd; Beutler, Bruce (July 31, 2012). "Yip1 domain family, member 6 (Yipf6) mutation induces spontaneous intestinal inflammation in mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12650–12655. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210366109. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3412000. PMID 22802641.

- ^ McAlpine, William; Sun, Lei; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Liu, Aijie; Jain, Ruchi; San Miguel, Miguel; Wang, Jianhui; Zhang, Zhao; Hayse, Braden; McAlpine, Sarah Grace; Choi, Jin Huk; Zhong, Xue; Ludwig, Sara; Russell, Jamie; Zhan, Xiaoming (December 4, 2018). "Excessive endosomal TLR signaling causes inflammatory disease in mice with defective SMCR8-WDR41-C9ORF72 complex function". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (49): E11523–E11531. doi:10.1073/pnas.1814753115. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 6298088. PMID 30442666.

- ^ McAlpine, William; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Choi, Jin Huk; San Miguel, Miguel; McAlpine, Sarah Grace; Russell, Jamie; Ludwig, Sara; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao; Zhan, Xiaoming; Choi, Mihwa; Wang, Tao; Bu, Chun Hui; Murray, Anne R.; Moresco, Eva Marie Y. (September 27, 2018). "The class I myosin MYO1D binds to lipid and protects against colitis". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 11 (9): dmm035923. doi:10.1242/dmm.035923. ISSN 1754-8411. PMC 6176994. PMID 30279225.

- ^ Wang, Kuan-Wen; Zhan, Xiaoming; McAlpine, William; Zhang, Zhao; Choi, Jin Huk; Shi, Hexin; Misawa, Takuma; Yue, Tao; Zhang, Duanwu; Wang, Ying; Ludwig, Sara; Russell, Jamie; Tang, Miao; Li, Xiaohong; Murray, Anne R. (June 4, 2019). "Enhanced susceptibility to chemically induced colitis caused by excessive endosomal TLR signaling in LRBA-deficient mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (23): 11380–11389. doi:10.1073/pnas.1901407116. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 6561264. PMID 31097594.

- ^ Turer, Emre; McAlpine, William; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Lu, Tianshi; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao; Zhan, Xiaoming; Wang, Tao; Zhan, Xiaowei; Bu, Chun-Hui; Murray, Anne R.; Beutler, Bruce (February 14, 2017). "Creatine maintains intestinal homeostasis and protects against colitis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (7): E1273–E1281. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621400114. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 5321020. PMID 28137860.

- ^ SoRelle, Jeffrey A.; Chen, Zhe; Wang, Jianhui; Yue, Tao; Choi, Jin Huk; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Zhong, Xue; Hildebrand, Sara; Russell, Jamie; Scott, Lindsay; Xu, Darui; Zhan, Xiaowei; Bu, Chun Hui; Wang, Tao; Choi, Mihwa (April 2021). "Dominant atopy risk mutations identified by mouse forward genetic analysis". Allergy. 76 (4): 1095–1108. doi:10.1111/all.14564. ISSN 1398-9995. PMC 7889751. PMID 32810290.

- ^ a b Chatenoud, Lucienne; Marquet, Cindy; Valette, Fabrice; Scott, Lindsay; Quan, Jiexia; Bu, Chun Hui; Hildebrand, Sara; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Bach, Jean-François; Beutler, Bruce (June 1, 2022). "Modulation of autoimmune diabetes by N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea- induced mutations in non-obese diabetic mice". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 15 (6): dmm049484. doi:10.1242/dmm.049484. ISSN 1754-8411. PMC 9178510. PMID 35502705.

- ^ a b Foray, Anne-Perrine; Candon, Sophie; Hildebrand, Sara; Marquet, Cindy; Valette, Fabrice; Pecquet, Coralie; Lemoine, Sebastien; Langa-Vives, Francina; Dumas, Michael; Hu, Peipei; Santamaria, Pere; You, Sylvaine; Lyon, Stephen; Scott, Lindsay; Bu, Chun Hui (November 23, 2021). "De novo germline mutation in the dual specificity phosphatase 10 gene accelerates autoimmune diabetes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (47): e2112032118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2112032118. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 8617500. PMID 34782469.

- ^ a b c Zhang, Zhao; Turer, Emre; Li, Xiaohong; Zhan, Xiaoming; Choi, Mihwa; Tang, Miao; Press, Amanda; Smith, Steven R.; Divoux, Adeline; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Beutler, Bruce (October 18, 2016). "Insulin resistance and diabetes caused by genetic or diet-induced KBTBD2 deficiency in mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (42): E6418–E6426. doi:10.1073/pnas.1614467113. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 5081616. PMID 27708159.

- ^ Turer, Emre E.; San Miguel, Miguel; Wang, Kuan-Wen; McAlpine, William; Ou, Feiya; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao; Zang, Zhao; Wang, Jianhui; Hayse, Braden; Evers, Bret; Zhan, Xiaoming; Russell, Jamie; Beutler, Bruce (December 18, 2018). "A viable hypomorphic Arnt2 mutation causes hyperphagic obesity, diabetes and hepatic steatosis". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 11 (12): dmm035451. doi:10.1242/dmm.035451. ISSN 1754-8411. PMC 6307907. PMID 30563851.

- ^ a b c Zhang, Zhao; Jiang, Yiao; Su, Lijing; Ludwig, Sara; Zhang, Xuechun; Tang, Miao; Li, Xiaohong; Anderton, Priscilla; Zhan, Xiaoming; Choi, Mihwa; Russell, Jamie; Bu, Chun-Hui; Lyon, Stephen; Xu, Darui; Hildebrand, Sara (November 1, 2022). "Obesity caused by an OVOL2 mutation reveals dual roles of OVOL2 in promoting thermogenesis and limiting white adipogenesis". Cell Metabolism. 34 (11): 1860–1874.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.018. ISSN 1932-7420. PMC 9633419. PMID 36228616.

- ^ a b Berger, Michael; Krebs, Philippe; Crozat, Karine; Li, Xiaohong; Croker, Ben A.; Siggs, Owen M.; Popkin, Daniel; Du, Xin; Lawson, Brian R.; Theofilopoulos, Argyrios N.; Xia, Yu; Khovananth, Kevin; Moresco, Eva Marie; Satoh, Takashi; Takeuchi, Osamu (April 2010). "An Slfn2 mutation causes lymphoid and myeloid immunodeficiency due to loss of immune cell quiescence". Nature Immunology. 11 (4): 335–343. doi:10.1038/ni.1847. ISSN 1529-2916. PMC 2861894. PMID 20190759.

- ^ Siggs, Owen M.; Arnold, Carrie N.; Huber, Christoph; Pirie, Elaine; Xia, Yu; Lin, Pei; Nemazee, David; Beutler, Bruce (May 2011). "The P4-type ATPase ATP11C is essential for B lymphopoiesis in adult bone marrow". Nature Immunology. 12 (5): 434–440. doi:10.1038/ni.2012. ISSN 1529-2916. PMC 3079768. PMID 21423172.

- ^ Siggs, Owen M.; Li, Xiaohong; Xia, Yu; Beutler, Bruce (January 16, 2012). "ZBTB1 is a determinant of lymphoid development". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 209 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1084/jem.20112084. ISSN 1540-9538. PMC 3260866. PMID 22201126.

- ^ a b Choi, Jin Huk; Han, Jonghee; Theodoropoulos, Panayotis C.; Zhong, Xue; Wang, Jianhui; Medler, Dawson; Ludwig, Sara; Zhan, Xiaoming; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao; Gallagher, Thomas; Yu, Gang; Beutler, Bruce (March 3, 2020). "Essential requirement for nicastrin in marginal zone and B-1 B cell development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (9): 4894–4901. doi:10.1073/pnas.1916645117. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 7060662. PMID 32071239.

- ^ a b Choi, Jin Huk; Zhong, Xue; McAlpine, William; Liao, Tzu-Chieh; Zhang, Duanwu; Fang, Beibei; Russell, Jamie; Ludwig, Sara; Nair-Gill, Evan; Zhang, Zhao; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Misawa, Takuma; Zhan, Xiaoming; Choi, Mihwa; Wang, Tao (May 10, 2019). "LMBR1L regulates lymphopoiesis through Wnt/β-catenin signaling". Science. 364 (6440): eaau0812. doi:10.1126/science.aau0812. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 7206793. PMID 31073040.

- ^ a b Choi, Jin Huk; Zhong, Xue; Zhang, Zhao; Su, Lijing; McAlpine, William; Misawa, Takuma; Liao, Tzu-Chieh; Zhan, Xiaoming; Russell, Jamie; Ludwig, Sara; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao; Anderton, Priscilla; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Beutler, Bruce (April 6, 2020). "Essential cell-extrinsic requirement for PDIA6 in lymphoid and myeloid development". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 217 (4): e20190006. doi:10.1084/jem.20190006. ISSN 1540-9538. PMC 7144532. PMID 31985756.

- ^ a b Zhang, Duanwu; Yue, Tao; Choi, Jin Huk; Nair-Gill, Evan; Zhong, Xue; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Zhan, Xiaoming; Li, Xiaohong; Choi, Mihwa; Tang, Miao; Quan, Jiexia; Hildebrand, Sara; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Beutler, Bruce (October 2019). "Syndromic immune disorder caused by a viable hypomorphic allele of spliceosome component Snrnp40". Nature Immunology. 20 (10): 1322–1334. doi:10.1038/s41590-019-0464-4. ISSN 1529-2916. PMC 7179765. PMID 31427773.

- ^ a b Zhong, Xue; Choi, Jin Huk; Hildebrand, Sara; Ludwig, Sara; Wang, Jianhui; Nair-Gill, Evan; Liao, Tzu-Chieh; Moresco, James J.; Liu, Aijie; Quan, Jiexia; Sun, Qihua; Zhang, Duanwu; Zhan, Xiaoming; Choi, Mihwa; Li, Xiaohong (May 3, 2022). "RNPS1 inhibits excessive tumor necrosis factor/tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling to support hematopoiesis in mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 119 (18): e2200128119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2200128119. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 9170173. PMID 35482923.

- ^ a b Zhong, Xue; Su, Lijing; Yang, Yi; Nair-Gill, Evan; Tang, Miao; Anderton, Priscilla; Li, Xiaohong; Wang, Jianhui; Zhan, Xiaoming; Tomchick, Diana R.; Brautigam, Chad A.; Moresco, Eva Marie Y.; Choi, Jin Huk; Beutler, Bruce (April 14, 2020). "Genetic and structural studies of RABL3 reveal an essential role in lymphoid development and function". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (15): 8563–8572. doi:10.1073/pnas.2000703117. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 7165429. PMID 32220963.

- ^ a b Misawa, Takuma; SoRelle, Jeffrey A.; Choi, Jin Huk; Yue, Tao; Wang, Kuan-Wen; McAlpine, William; Wang, Jianhui; Liu, Aijie; Tabeta, Koichi; Turer, Emre E.; Evers, Bret; Nair-Gill, Evan; Poddar, Subhajit; Su, Lijing; Ou, Feiya (January 24, 2020). "Mutual inhibition between Prkd2 and Bcl6 controls T follicular helper cell differentiation". Science Immunology. 5 (43): eaaz0085. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz0085. ISSN 2470-9468. PMC 7278039. PMID 31980486.

- ^ Arnold, Carrie N.; Pirie, Elaine; Dosenovic, Pia; McInerney, Gerald M.; Xia, Yu; Wang, Nathaniel; Li, Xiaohong; Siggs, Owen M.; Karlsson Hedestam, Gunilla B.; Beutler, Bruce (July 31, 2012). "A forward genetic screen reveals roles for Nfkbid, Zeb1, and Ruvbl2 in humoral immunity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12286–12293. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209134109. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3411946. PMID 22761313.

- ^ Choi, Jin Huk; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Zhang, Duanwu; Zhan, Xiaowei; Wang, Tao; Bu, Chun-Hui; Behrendt, Cassie L.; Zeng, Ming; Wang, Ying; Misawa, Takuma; Li, Xiaohong; Tang, Miao; Zhan, Xiaoming; Scott, Lindsay; Hildebrand, Sara (February 14, 2017). "IgD class switching is initiated by microbiota and limited to mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (7): E1196–E1204. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621258114. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 5321007. PMID 28137874.

- ^ Yue, Tao; Zhan, Xiaoming; Zhang, Duanwu; Jain, Ruchi; Wang, Kuan-Wen; Choi, Jin Huk; Misawa, Takuma; Su, Lijing; Quan, Jiexia; Hildebrand, Sara; Xu, Darui; Li, Xiaohong; Turer, Emre; Sun, Lei; Moresco, Eva Marie Y. (May 14, 2021). "SLFN2 protection of tRNAs from stress-induced cleavage is essential for T cell-mediated immunity". Science. 372 (6543): eaba4220. doi:10.1126/science.aba4220. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 8442736. PMID 33986151.

- ^ a b Nair-Gill, Evan; Bonora, Massimo; Zhong, Xue; Liu, Aijie; Miranda, Amber; Stewart, Nathan; Ludwig, Sara; Russell, Jamie; Gallagher, Thomas; Pinton, Paolo; Beutler, Bruce (May 3, 2021). "Calcium flux control by Pacs1-Wdr37 promotes lymphocyte quiescence and lymphoproliferative diseases". The EMBO journal. 40 (9): e104888. doi:10.15252/embj.2020104888. ISSN 1460-2075. PMC 8090855. PMID 33630350.

- ^ Du, X.; She, E.; Gelbart, T.; Truksa, J.; Lee, P.; Xia, Y.; Khovananth, K.; Mudd, S.; Mann, N.; Moresco, E. M. Y.; Beutler, E.; Beutler, B. (2008). "The serine protease TMPRSS6 is required to sense iron deficiency". Science. 320 (5879): 1088–1092. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1088D. doi:10.1126/science.1157121. PMC 2430097. PMID 18451267.

- ^ Du, X.; Schwander, M.; Moresco, E. M. Y.; Viviani, P.; Haller, C.; Hildebrand, M. S.; Pak, K.; Tarantino, L.; Roberts, A.; Richardson, H.; Koob, G.; Najmabadi, H.; Ryan, A. F.; Smith, R. J. H.; Muller, U.; Beutler, B. (2008). "A catechol-O-methyltransferase that is essential for auditory function in mice and humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (38): 14609–14614. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10514609D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807219105. PMC 2567147. PMID 18794526.

- ^ Blasius, Amanda L.; Brandl, Katharina; Crozat, Karine; Xia, Yu; Khovananth, Kevin; Krebs, Philippe; Smart, Nora G.; Zampolli, Antonella; Ruggeri, Zaverio M.; Beutler, Bruce A. (February 24, 2009). "Mice with mutations of Dock7 have generalized hypopigmentation and white-spotting but show normal neurological function". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (8): 2706–2711. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813208106. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2650330. PMID 19202056.