HFE (gene): Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Alter: pages. Add: pmc, pages, issue, volume. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | Category:Genes on human chromosome 6 | #UCB_Category 765/772 |

m proofreading and wikilinking |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Distinguish|hemochromatosis}} |

{{Distinguish|hemochromatosis}} |

||

{{Infobox gene}} |

{{Infobox gene}} |

||

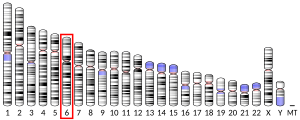

'''Human homeostatic iron regulator protein, '''also known as the '''HFE protein''' ('''H'''igh '''FE'''2+), is a [[protein]] which in humans is encoded by the ''HFE'' [[gene]]. The ''HFE'' gene is located on short arm of [[chromosome 6]] at location 6p22.2 <ref>{{cite web | title = HGNC: HFE| url = https://www.genenames.org/data/gene-symbol-report/#!/hgnc_id/4886| access-date =2019-08-30 }}</ref> |

'''Human homeostatic iron regulator protein, '''also known as the '''HFE protein''' ('''H'''igh '''FE'''2+), is a [[Transmembrane protein|transmembrane]] [[protein]] which in humans is encoded by the ''HFE'' [[gene]]. The ''HFE'' gene is located on short arm of [[chromosome 6]] at location 6p22.2 <ref>{{cite web | title = HGNC: HFE| url = https://www.genenames.org/data/gene-symbol-report/#!/hgnc_id/4886| access-date =2019-08-30 }}</ref> |

||

== Function == |

== Function == |

||

The protein encoded by this gene is |

The protein encoded by this gene is an [[Integral membrane protein|integral membrane]] protein that is similar to [[MHC class I]]-type proteins and associates with [[beta-2 microglobulin]] (beta2M). It is thought that this protein functions to regulate circulating iron uptake by regulating the interaction of the [[transferrin receptor]] with [[transferrin]].<ref>{{cite web | title = NCBI Gene: HFE homeostatic iron regulator| url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3077| access-date = 30 November 2020 | publisher = National Center for Biotechnology Information}}{{PD-notice}}</ref> |

||

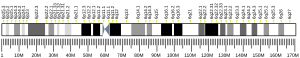

The ''HFE'' gene contains 7 [[exon]]s spanning 12 kb.<ref name="Feder 1996">{{cite journal|last1=Feder|first1=JN|last2=Gnirke|first2=A|last3=Thomas|first3=W|last4=Tsuchihashi|first4=Z|last5=Ruddy|first5=DA|last6=Basava|first6=A|last7=Dormishian|first7=F|last8=Domingo R|first8=Jr|last9=Ellis|first9=MC|last10=Fullan|first10=A|last11=Hinton|first11=LM|last12=Jones|first12=NL|last13=Kimmel|first13=BE|last14=Kronmal|first14=GS|last15=Lauer|first15=P|last16=Lee|first16=VK|last17=Loeb|first17=DB|last18=Mapa|first18=FA|last19=McClelland|first19=E|last20=Meyer|first20=NC|last21=Mintier|first21=GA|last22=Moeller|first22=N|last23=Moore|first23=T|last24=Morikang|first24=E|last25=Prass|first25=CE|last26=Quintana|first26=L|last27=Starnes|first27=SM|last28=Schatzman|first28=RC|last29=Brunke|first29=KJ|last30=Drayna|first30=DT|last31=Risch|first31=NJ|last32=Bacon|first32=BR|last33=Wolff|first33=RK|title=A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis|journal=Nature Genetics|date=August 1996|volume=13|issue=4|pages=399–408|pmid=8696333|doi=10.1038/ng0896-399|s2cid=26239768}}</ref> The full-length transcript represents 6 exons.<ref name="Dorak">{{cite web|last1=Dorak|first1=M.T.|date=March 2008|title=''HFE'' (hemochromatosis)|url=http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Genes/GC_HFE.html|access-date=17 June 2020|website=Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology|archive-date=29 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170929113814/http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Genes/GC_HFE.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

The ''HFE'' gene contains 7 [[exon]]s spanning 12 kb.<ref name="Feder 1996">{{cite journal|last1=Feder|first1=JN|last2=Gnirke|first2=A|last3=Thomas|first3=W|last4=Tsuchihashi|first4=Z|last5=Ruddy|first5=DA|last6=Basava|first6=A|last7=Dormishian|first7=F|last8=Domingo R|first8=Jr|last9=Ellis|first9=MC|last10=Fullan|first10=A|last11=Hinton|first11=LM|last12=Jones|first12=NL|last13=Kimmel|first13=BE|last14=Kronmal|first14=GS|last15=Lauer|first15=P|last16=Lee|first16=VK|last17=Loeb|first17=DB|last18=Mapa|first18=FA|last19=McClelland|first19=E|last20=Meyer|first20=NC|last21=Mintier|first21=GA|last22=Moeller|first22=N|last23=Moore|first23=T|last24=Morikang|first24=E|last25=Prass|first25=CE|last26=Quintana|first26=L|last27=Starnes|first27=SM|last28=Schatzman|first28=RC|last29=Brunke|first29=KJ|last30=Drayna|first30=DT|last31=Risch|first31=NJ|last32=Bacon|first32=BR|last33=Wolff|first33=RK|title=A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis|journal=Nature Genetics|date=August 1996|volume=13|issue=4|pages=399–408|pmid=8696333|doi=10.1038/ng0896-399|s2cid=26239768}}</ref> The full-length [[Transcription (biology)|transcript]] represents 6 exons.<ref name="Dorak">{{cite web|last1=Dorak|first1=M.T.|date=March 2008|title=''HFE'' (hemochromatosis)|url=http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Genes/GC_HFE.html|access-date=17 June 2020|website=Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology|archive-date=29 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170929113814/http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Genes/GC_HFE.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

HFE protein is composed of 343 amino acids. There are several components, in sequence: a signal peptide (initial part of the protein), an extracellular transferrin receptor-binding region (α1 and α2), a portion that resembles immunoglobulin molecules (α3), a transmembrane region that anchors the protein in the cell membrane, and a short cytoplasmic tail.<ref name="Feder 1996" /> |

HFE protein is composed of 343 [[Amino acid|amino acids]]. There are several components, in sequence: a signal peptide (initial part of the protein), an extracellular transferrin receptor-binding region (α1 and α2), a portion that resembles immunoglobulin molecules (α3), a transmembrane region that anchors the protein in the cell membrane, and a short cytoplasmic tail.<ref name="Feder 1996" /> |

||

HFE expression is subjected to [[alternative splicing]]. The predominant HFE full-length transcript has ~4.2 kb.<ref name=martins /> Alternative HFE splicing variants may serve as iron regulatory mechanisms in specific cells or tissues.<ref name=martins>{{cite journal|last1=Martins|first1=R|last2=Silva|first2=B|last3=Proença|first3=D|last4=Faustino|first4=P|title=Differential ''HFE'' gene expression is regulated by alternative splicing in human tissues|journal=PLOS ONE|date=3 March 2011|volume=6|issue=3|pages=e17542|pmid=21407826|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0017542|pmc=3048171|bibcode=2011PLoSO...617542M|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

HFE expression is subjected to [[alternative splicing]]. The predominant HFE full-length transcript has ~4.2 kb.<ref name=martins /> Alternative HFE splicing variants may serve as iron regulatory mechanisms in specific cells or tissues.<ref name=martins>{{cite journal|last1=Martins|first1=R|last2=Silva|first2=B|last3=Proença|first3=D|last4=Faustino|first4=P|title=Differential ''HFE'' gene expression is regulated by alternative splicing in human tissues|journal=PLOS ONE|date=3 March 2011|volume=6|issue=3|pages=e17542|pmid=21407826|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0017542|pmc=3048171|bibcode=2011PLoSO...617542M|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

HFE is prominent in small intestinal absorptive cells,<ref name=waheed>{{cite journal|last1=Waheed|first1=A|last2=Parkkila|first2=S|last3=Saarnio|first3=J|last4=Fleming|first4=RE|last5=Zhou|first5=XY|last6=Tomatsu|first6=S|last7=Britton|first7=RS|last8=Bacon|first8=BR|last9=Sly|first9=WS|title=Association of HFE protein with transferrin receptor in crypt enterocytes of human duodenum|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|date=16 February 1999|volume=96|issue=4|pages=1579–84|pmid=9990067|doi=10.1073/pnas.96.4.1579|pmc=15523|bibcode=1999PNAS...96.1579W|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=Griffiths>{{cite journal|last1=Griffiths|first1=WJ|last2=Kelly|first2=AL|last3=Smith|first3=SJ|last4=Cox|first4=TM|title=Localization of iron transport and regulatory proteins in human cells|journal=QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians|date=September 2000|volume=93|issue=9|pages=575–87|pmid=10984552|doi=10.1093/qjmed/93.9.575}}</ref> gastric epithelial cells, tissue macrophages, and blood monocytes and granulocytes,<ref name=Griffiths /><ref name="Parkkila Haematologica">{{cite journal|last1=Parkkila|first1=S|last2=Parkkila|first2=AK|last3=Waheed|first3=A|last4=Britton|first4=RS|last5=Zhou|first5=XY|last6=Fleming|first6=RE|last7=Tomatsu|first7=S|last8=Bacon|first8=BR|last9=Sly|first9=WS|title=Cell surface expression of HFE protein in epithelial cells, macrophages, and monocytes|journal=Haematologica|date=April 2000|volume=85|issue=4|pages=340–5|pmid=10756356}}</ref> and the syncytiotrophoblast, an iron transport tissue in the placenta.<ref name="Parkkila PNAS">{{cite journal|last1=Parkkila|first1=S|last2=Waheed|first2=A|last3=Britton|first3=RS|last4=Bacon|first4=BR|last5=Zhou|first5=XY|last6=Tomatsu|first6=S|last7=Fleming|first7=RE|last8=Sly|first8=WS|title=Association of the transferrin receptor in human placenta with HFE, the protein defective in hereditary hemochromatosis|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|date=25 November 1997|volume=94|issue=24|pages=13198–202|pmid=9371823|doi=10.1073/pnas.94.24.13198|pmc=24286|bibcode=1997PNAS...9413198P|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

HFE is prominent in small intestinal absorptive cells,<ref name=waheed>{{cite journal|last1=Waheed|first1=A|last2=Parkkila|first2=S|last3=Saarnio|first3=J|last4=Fleming|first4=RE|last5=Zhou|first5=XY|last6=Tomatsu|first6=S|last7=Britton|first7=RS|last8=Bacon|first8=BR|last9=Sly|first9=WS|title=Association of HFE protein with transferrin receptor in crypt enterocytes of human duodenum|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|date=16 February 1999|volume=96|issue=4|pages=1579–84|pmid=9990067|doi=10.1073/pnas.96.4.1579|pmc=15523|bibcode=1999PNAS...96.1579W|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=Griffiths>{{cite journal|last1=Griffiths|first1=WJ|last2=Kelly|first2=AL|last3=Smith|first3=SJ|last4=Cox|first4=TM|title=Localization of iron transport and regulatory proteins in human cells|journal=QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians|date=September 2000|volume=93|issue=9|pages=575–87|pmid=10984552|doi=10.1093/qjmed/93.9.575}}</ref> gastric [[Epithelium|epithelial]] cells, tissue [[Macrophage|macrophages]], and blood [[Monocyte|monocytes]] and [[Granulocyte|granulocytes]],<ref name=Griffiths /><ref name="Parkkila Haematologica">{{cite journal|last1=Parkkila|first1=S|last2=Parkkila|first2=AK|last3=Waheed|first3=A|last4=Britton|first4=RS|last5=Zhou|first5=XY|last6=Fleming|first6=RE|last7=Tomatsu|first7=S|last8=Bacon|first8=BR|last9=Sly|first9=WS|title=Cell surface expression of HFE protein in epithelial cells, macrophages, and monocytes|journal=Haematologica|date=April 2000|volume=85|issue=4|pages=340–5|pmid=10756356}}</ref> and the syncytiotrophoblast, an iron transport tissue in the placenta.<ref name="Parkkila PNAS">{{cite journal|last1=Parkkila|first1=S|last2=Waheed|first2=A|last3=Britton|first3=RS|last4=Bacon|first4=BR|last5=Zhou|first5=XY|last6=Tomatsu|first6=S|last7=Fleming|first7=RE|last8=Sly|first8=WS|title=Association of the transferrin receptor in human placenta with HFE, the protein defective in hereditary hemochromatosis|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|date=25 November 1997|volume=94|issue=24|pages=13198–202|pmid=9371823|doi=10.1073/pnas.94.24.13198|pmc=24286|bibcode=1997PNAS...9413198P|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

== Clinical significance == |

== Clinical significance == |

||

The iron storage disorder [[HFE hereditary haemochromatosis|hereditary hemochromatosis]] (HHC) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that usually results from defects in this gene. |

The iron storage disorder [[HFE hereditary haemochromatosis|hereditary hemochromatosis]] (HHC) is an [[Dominance (genetics)|autosomal recessive]] genetic disorder that usually results from defects in this gene. |

||

The disease-causing genetic variant most commonly associated with hemochromatosis is p. C282Y.<ref name="pmid35699322">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hsu CC, Senussi NH, Fertrin KY, Kowdley KV |title=Iron overload disorders |journal=Hepatol Commun|date=June 2022 |volume=6 |issue=8 |pages=1842–1854 |pmid=35699322 |doi=10.1002/hep4.2012|pmc=9315134 }}</ref> About 1/200 of people of Northern European origin have two copies of this variant; they, particularly males, are at high risk of developing hemochromatosis.<ref>{{cite web | title = Hemochromatosis | url = http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/hemochromatosis/index.htm | access-date = 20 August 2009 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070318063028/http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/hemochromatosis/index.htm | archive-date = 18 March 2007 | url-status = dead }}</ref> This variant may also be one of the factors modifying [[Wilson's disease]] [[phenotype]], making the symptoms of the disease appear earlier.<ref name="pmid33175593">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gromadzka G, Wierzbicka DW, Przybyłkowski A, Litwin T | title = Effect of homeostatic iron regulator protein gene mutation on Wilson's disease clinical manifestation: original data and literature review | journal = The International Journal of Neuroscience | pages = 894–900 | date = November 2020 | volume = 132 | issue = 9 | pmid = 33175593 | doi = 10.1080/00207454.2020.1849190| s2cid = 226310435 }}</ref> |

The disease-causing genetic variant most commonly associated with hemochromatosis is p. C282Y.<ref name="pmid35699322">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hsu CC, Senussi NH, Fertrin KY, Kowdley KV |title=Iron overload disorders |journal=Hepatol Commun|date=June 2022 |volume=6 |issue=8 |pages=1842–1854 |pmid=35699322 |doi=10.1002/hep4.2012|pmc=9315134 }}</ref> About 1/200 of people of Northern European origin have two copies of this variant; they, particularly males, are at high risk of developing hemochromatosis.<ref>{{cite web | title = Hemochromatosis | url = http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/hemochromatosis/index.htm | access-date = 20 August 2009 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070318063028/http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/hemochromatosis/index.htm | archive-date = 18 March 2007 | url-status = dead }}</ref> This variant may also be one of the factors modifying [[Wilson's disease]] [[phenotype]], making the symptoms of the disease appear earlier.<ref name="pmid33175593">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gromadzka G, Wierzbicka DW, Przybyłkowski A, Litwin T | title = Effect of homeostatic iron regulator protein gene mutation on Wilson's disease clinical manifestation: original data and literature review | journal = The International Journal of Neuroscience | pages = 894–900 | date = November 2020 | volume = 132 | issue = 9 | pmid = 33175593 | doi = 10.1080/00207454.2020.1849190| s2cid = 226310435 }}</ref> |

||

Allele frequencies of ''HFE'' C282Y in ethnically diverse western European white populations are 5-14%<ref name="Porto 2000">{{cite book|last1=Porto|first1=Graca|last2=de Sousa|first2=Maria|editor1-last=Barton|editor1-first=James C.|editor2-last=Edwards|editor2-first=Corwin Q.|title=Variation of hemochromatosis prevalence and genotype in national groups|date=2000|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=In: Hemochromatosis: Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment|isbn=978-0521593809|pages=51–62}}</ref><ref name="Ryan and Ireland">{{cite journal|last1=Ryan|first1=E|last2=O'Keane|first2=C|last3=Crowe|first3=J|title=Hemochromatosis in Ireland and ''HFE''|journal=Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases|date=December 1998|volume=24|issue=4|pages=428–32|pmid=9851896|doi=10.1006/bcmd.1998.0211}}</ref> and in North American non-Hispanic whites are 6-7%.<ref name="Acton Ethn Dis">{{cite journal|last1=Acton|first1=RT|last2=Barton|first2=JC|last3=Snively|first3=BM|last4=McLaren|first4=CE|last5=Adams|first5=PC|last6=Harris|first6=EL|last7=Speechley|first7=MR|last8=McLaren|first8=GD|last9=Dawkins|first9=FW|last10=Leiendecker-Foster|first10=C|last11=Holup|first11=JL|last12=Balasubramanyam|first12=A|last13=Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening Study Research Investigators|title=Geographic and racial/ethnic differences in ''HFE'' mutation frequencies in the Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening (HEIRS) Study|journal=Ethnicity & Disease|date=2006|volume=16|issue=4|pages=815–21|pmid=17061732}}</ref> C282Y exists as a polymorphism only in Western European white and derivative populations, although C282Y may have arisen independently in non-whites outside Europe.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Rochette|first1=J|last2=Pointon|first2=JJ|last3=Fisher|first3=CA|last4=Perera|first4=G|last5=Arambepola|first5=M|last6=Arichchi|first6=DS|last7=De Silva|first7=S|last8=Vandwalle|first8=JL|last9=Monti|first9=JP|last10=Old|first10=JM|last11=Merryweather-Clarke|first11=AT|last12=Weatherall|first12=DJ|last13=Robson|first13=KJ|title=Multicentric origin of hemochromatosis gene (''HFE'') mutations|journal=American Journal of Human Genetics|date=April 1999|volume=64|issue=4|pages=1056–62|pmid=10090890|doi=10.1086/302318|pmc=1377829}}</ref> |

Allele frequencies of ''HFE'' C282Y in ethnically diverse western European white populations are 5-14%<ref name="Porto 2000">{{cite book|last1=Porto|first1=Graca|last2=de Sousa|first2=Maria|editor1-last=Barton|editor1-first=James C.|editor2-last=Edwards|editor2-first=Corwin Q.|title=Variation of hemochromatosis prevalence and genotype in national groups|date=2000|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=In: Hemochromatosis: Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment|isbn=978-0521593809|pages=51–62}}</ref><ref name="Ryan and Ireland">{{cite journal|last1=Ryan|first1=E|last2=O'Keane|first2=C|last3=Crowe|first3=J|title=Hemochromatosis in Ireland and ''HFE''|journal=Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases|date=December 1998|volume=24|issue=4|pages=428–32|pmid=9851896|doi=10.1006/bcmd.1998.0211}}</ref> and in North American non-Hispanic whites are 6-7%.<ref name="Acton Ethn Dis">{{cite journal|last1=Acton|first1=RT|last2=Barton|first2=JC|last3=Snively|first3=BM|last4=McLaren|first4=CE|last5=Adams|first5=PC|last6=Harris|first6=EL|last7=Speechley|first7=MR|last8=McLaren|first8=GD|last9=Dawkins|first9=FW|last10=Leiendecker-Foster|first10=C|last11=Holup|first11=JL|last12=Balasubramanyam|first12=A|last13=Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening Study Research Investigators|title=Geographic and racial/ethnic differences in ''HFE'' mutation frequencies in the Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening (HEIRS) Study|journal=Ethnicity & Disease|date=2006|volume=16|issue=4|pages=815–21|pmid=17061732}}</ref> C282Y exists as a [[Polymorphism (biology)|polymorphism]] only in Western European white and derivative populations, although C282Y may have arisen independently in non-whites outside Europe.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Rochette|first1=J|last2=Pointon|first2=JJ|last3=Fisher|first3=CA|last4=Perera|first4=G|last5=Arambepola|first5=M|last6=Arichchi|first6=DS|last7=De Silva|first7=S|last8=Vandwalle|first8=JL|last9=Monti|first9=JP|last10=Old|first10=JM|last11=Merryweather-Clarke|first11=AT|last12=Weatherall|first12=DJ|last13=Robson|first13=KJ|title=Multicentric origin of hemochromatosis gene (''HFE'') mutations|journal=American Journal of Human Genetics|date=April 1999|volume=64|issue=4|pages=1056–62|pmid=10090890|doi=10.1086/302318|pmc=1377829}}</ref> |

||

''HFE'' H63D is cosmopolitan but occurs with greatest frequency in |

''HFE'' H63D is cosmopolitan but occurs with greatest frequency in individuals of European descent.<ref name="Merryweather-Clarke 1997">{{cite journal|last1=Merryweather-Clarke|first1=AT|last2=Pointon|first2=JJ|last3=Shearman|first3=JD|last4=Robson|first4=KJ|title=Global prevalence of putative haemochromatosis mutations|journal=Journal of Medical Genetics|date=April 1997|volume=34|issue=4|pages=275–8|pmid=9138148|doi=10.1136/jmg.34.4.275|pmc=1050911}}</ref><ref name="Merryweather-clarke 2000">{{cite journal|last1=Merryweather-Clarke|first1=AT|last2=Pointon|first2=JJ|last3=Jouanolle|first3=AM|last4=Rochette|first4=J|last5=Robson|first5=KJ|title=Geography of ''HFE'' C282Y and H63D mutations|journal=Genetic Testing|date=2000|volume=4|issue=2|pages=183–98|pmid=10953959|doi=10.1089/10906570050114902}}</ref> Allele frequencies of H63D in ethnically diverse western European populations are 10-29%.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Fairbanks|first1=Virgil F.|editor1-last=Barton|editor1-first=James C.|editor2-last=Edwards|editor2-first=Corwin Q.|title=Hemochromatosis: population genetics. In: Hemochromatosis: Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment|date=2000|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0521593809|pages=42–50}}</ref> and in North American non-Hispanic whites are 14-15%.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Acton|first1=RT|last2=Barton|first2=JC|last3=Snively|first3=BM|last4=McLaren|first4=CE|last5=Adams|first5=PC|last6=Harris|first6=EL|last7=Speechley|first7=MR|last8=McLaren|first8=GD|last9=Dawkins|first9=FW|last10=Leiendecker-Foster|first10=C|last11=Holup|first11=JL|last12=Balasubramanyam|first12=A|last13=Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening Study Research Investigators|title=Geographic and racial/ethnic differences in ''HFE'' mutation frequencies in the Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening (HEIRS) Study|journal=Ethnicity & Disease|date=2000|volume=16|issue=4|pages=815–21|pmid=17061732}}</ref> |

||

At least 42 mutations involving ''HFE'' introns and exons have been discovered, most of them in persons with hemochromatosis or their family members.<ref name="Edwards and Barton">{{cite book|last1=Edwards|first1=Corwin Q.|last2=Barton|first2=James C.|editor1-last=Greer|editor1-first=John P.|editor2-last=Arber|editor2-first=Daniel A.|editor3-last=Glader|editor3-first=Bertil|editor4-last=List|editor4-first=Alan F.|editor5-last=Means|editor5-first=Robert T., Jr.|editor6-last=Paraskevas|editor6-first=Frixos|editor7-last=Rodgers|editor7-first=George M.|title=Hemochromatosis. In: Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology|date=2014|publisher=Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|isbn=9781451172683|pages=662–681}}</ref> Most of these mutations are rare. Many of the mutations cause or probably cause hemochromatosis phenotypes, often in compound heterozygosity with ''HFE'' C282Y. Other mutations are either synonymous or their effect on iron phenotypes, if any, has not been demonstrated.<ref name="Edwards and Barton" /> |

At least 42 mutations involving ''HFE'' introns and exons have been discovered, most of them in persons with hemochromatosis or their family members.<ref name="Edwards and Barton">{{cite book|last1=Edwards|first1=Corwin Q.|last2=Barton|first2=James C.|editor1-last=Greer|editor1-first=John P.|editor2-last=Arber|editor2-first=Daniel A.|editor3-last=Glader|editor3-first=Bertil|editor4-last=List|editor4-first=Alan F.|editor5-last=Means|editor5-first=Robert T., Jr.|editor6-last=Paraskevas|editor6-first=Frixos|editor7-last=Rodgers|editor7-first=George M.|title=Hemochromatosis. In: Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology|date=2014|publisher=Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|isbn=9781451172683|pages=662–681}}</ref> Most of these mutations are rare. Many of the mutations cause or probably cause hemochromatosis phenotypes, often in compound heterozygosity with ''HFE'' C282Y. Other mutations are either synonymous or their effect on iron phenotypes, if any, has not been demonstrated.<ref name="Edwards and Barton" /> |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

== ''Hfe'' knockout mice == |

== ''Hfe'' knockout mice == |

||

It is possible to delete part or all of a gene of interest in mice (or other experimental animals) as a means of studying function of the gene and its protein. Such mice are called |

It is possible to delete part or all of a gene of interest in mice (or other experimental animals) as a means of studying function of the gene and its protein. Such mice are called “[[Gene knockout|knockouts]]” with respect to the deleted gene. ''Hfe'' is the mouse equivalent of the human hemochromatosis gene ''HFE''. The protein encoded by ''HFE'' is Hfe. Mice homozygous (two abnormal gene copies) for a targeted knockout of all six transcribed ''Hfe'' exons are designated ''Hfe''−/−.<ref name=Zhou>{{cite journal|last1=Zhou|first1=XY|last2=Tomatsu|first2=S|last3=Fleming|first3=RE|last4=Parkkila|first4=S|last5=Waheed|first5=A|last6=Jiang|first6=J|last7=Fei|first7=Y|last8=Brunt|first8=EM|last9=Ruddy|first9=DA|last10=Prass|first10=CE|last11=Schatzman|first11=RC|last12=O'Neill|first12=R|last13=Britton|first13=RS|last14=Bacon|first14=BR|last15=Sly|first15=WS|title=''HFE'' gene knockout produces mouse model of hereditary hemochromatosis|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|date=3 March 1998|volume=95|issue=5|pages=2492–7|pmid=9482913|doi=10.1073/pnas.95.5.2492|pmc=19387|bibcode=1998PNAS...95.2492Z|doi-access=free}}</ref> Iron-related traits of ''Hfe''−/− mice, including increased iron absorption and hepatic iron loading, are inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Thus, the ''Hfe''−/− mouse model simulates important genetic and physiological abnormalities of ''HFE'' hemochromatosis.<ref name=Zhou /> Other knockout mice were created to delete the second and third ''HFE'' exons (corresponding to α1 and α2 [[Protein domain|domains]] of Hfe). Mice homozygous for this deletion also had increased [[Duodenum|duodenal]] iron absorption, elevated [[Blood plasma|plasma]] iron and transferrin saturation levels, and iron overload, mainly in [[Hepatocyte|hepatocytes]].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Bahram|first1=S|last2=Gilfillan|first2=S|last3=Kühn|first3=LC|last4=Moret|first4=R|last5=Schulze|first5=JB|last6=Lebeau|first6=A|last7=Schümann|first7=K|title=Experimental hemochromatosis due to MHC class I HFE deficiency: immune status and iron metabolism|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|date=9 November 1999|volume=96|issue=23|pages=13312–7|pmid=10557317|doi=10.1073/pnas.96.23.13312|pmc=23944|bibcode=1999PNAS...9613312B|doi-access=free}}</ref> Mice have also been created that are homozygous for a [[missense mutation]] in ''Hfe'' (C282Y). These mice correspond to humans with hemochromatosis who are homozygous for ''HFE'' C282Y. These mice develop iron loading that is less severe than that of ''Hfe''−/− mice.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Levy|first1=JE|last2=Montross|first2=LK|last3=Cohen|first3=DE|last4=Fleming|first4=MD|last5=Andrews|first5=NC|title=The C282Y mutation causing hereditary hemochromatosis does not produce a null allele|journal=Blood|date=1 July 1999|volume=94|issue=1|pages=9–11|pmid=10381492|doi=10.1182/blood.V94.1.9.413a43_9_11|s2cid=12722648 }}</ref> |

||

== ''HFE'' mutations and iron overload in other animals == |

== ''HFE'' mutations and iron overload in other animals == |

||

Revision as of 23:37, 20 March 2023

Human homeostatic iron regulator protein, also known as the HFE protein (High FE2+), is a transmembrane protein which in humans is encoded by the HFE gene. The HFE gene is located on short arm of chromosome 6 at location 6p22.2 [5]

Function

The protein encoded by this gene is an integral membrane protein that is similar to MHC class I-type proteins and associates with beta-2 microglobulin (beta2M). It is thought that this protein functions to regulate circulating iron uptake by regulating the interaction of the transferrin receptor with transferrin.[6]

The HFE gene contains 7 exons spanning 12 kb.[7] The full-length transcript represents 6 exons.[8]

HFE protein is composed of 343 amino acids. There are several components, in sequence: a signal peptide (initial part of the protein), an extracellular transferrin receptor-binding region (α1 and α2), a portion that resembles immunoglobulin molecules (α3), a transmembrane region that anchors the protein in the cell membrane, and a short cytoplasmic tail.[7]

HFE expression is subjected to alternative splicing. The predominant HFE full-length transcript has ~4.2 kb.[9] Alternative HFE splicing variants may serve as iron regulatory mechanisms in specific cells or tissues.[9]

HFE is prominent in small intestinal absorptive cells,[10][11] gastric epithelial cells, tissue macrophages, and blood monocytes and granulocytes,[11][12] and the syncytiotrophoblast, an iron transport tissue in the placenta.[13]

Clinical significance

The iron storage disorder hereditary hemochromatosis (HHC) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that usually results from defects in this gene.

The disease-causing genetic variant most commonly associated with hemochromatosis is p. C282Y.[14] About 1/200 of people of Northern European origin have two copies of this variant; they, particularly males, are at high risk of developing hemochromatosis.[15] This variant may also be one of the factors modifying Wilson's disease phenotype, making the symptoms of the disease appear earlier.[16]

Allele frequencies of HFE C282Y in ethnically diverse western European white populations are 5-14%[17][18] and in North American non-Hispanic whites are 6-7%.[19] C282Y exists as a polymorphism only in Western European white and derivative populations, although C282Y may have arisen independently in non-whites outside Europe.[20]

HFE H63D is cosmopolitan but occurs with greatest frequency in individuals of European descent.[21][22] Allele frequencies of H63D in ethnically diverse western European populations are 10-29%.[23] and in North American non-Hispanic whites are 14-15%.[24]

At least 42 mutations involving HFE introns and exons have been discovered, most of them in persons with hemochromatosis or their family members.[25] Most of these mutations are rare. Many of the mutations cause or probably cause hemochromatosis phenotypes, often in compound heterozygosity with HFE C282Y. Other mutations are either synonymous or their effect on iron phenotypes, if any, has not been demonstrated.[25]

Interactions

The HFE protein interacts with the transferrin receptor TFRC.[26][27] Its primary mode of action is the regulation of the iron storage hormone hepcidin.[28]

Hfe knockout mice

It is possible to delete part or all of a gene of interest in mice (or other experimental animals) as a means of studying function of the gene and its protein. Such mice are called “knockouts” with respect to the deleted gene. Hfe is the mouse equivalent of the human hemochromatosis gene HFE. The protein encoded by HFE is Hfe. Mice homozygous (two abnormal gene copies) for a targeted knockout of all six transcribed Hfe exons are designated Hfe−/−.[29] Iron-related traits of Hfe−/− mice, including increased iron absorption and hepatic iron loading, are inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Thus, the Hfe−/− mouse model simulates important genetic and physiological abnormalities of HFE hemochromatosis.[29] Other knockout mice were created to delete the second and third HFE exons (corresponding to α1 and α2 domains of Hfe). Mice homozygous for this deletion also had increased duodenal iron absorption, elevated plasma iron and transferrin saturation levels, and iron overload, mainly in hepatocytes.[30] Mice have also been created that are homozygous for a missense mutation in Hfe (C282Y). These mice correspond to humans with hemochromatosis who are homozygous for HFE C282Y. These mice develop iron loading that is less severe than that of Hfe−/− mice.[31]

HFE mutations and iron overload in other animals

The black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) can develop iron overload. To determine whether the HFE gene of black rhinoceroses has undergone mutation as an adaptive mechanism to improve iron absorption from iron-poor diets, Beutler et al. sequenced the entire HFE coding region of four species of rhinoceros (two browsing and two grazing species). Although HFE was well conserved across the species, numerous nucleotide differences were found between rhinoceros and human or mouse, some of which changed deduced amino acids. Only one allele, p.S88T in the black rhinoceros, was a candidate that might adversely affect HFE function. p.S88T occurs in a highly conserved region involved in the interaction of HFE and TfR1.[32]

See also

Notes

The 2015 version of this article was updated by an external expert under a dual publication model. The corresponding academic peer reviewed article was published in Gene and can be cited as: James C Barton; Corwin Q Edwards; Ronald T Acton (9 October 2015). "HFE gene: Structure, function, mutations, and associated iron abnormalities". Gene. Gene Wiki Review Series. 574 (2): 179–192. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2015.10.009. ISSN 0378-1119. PMC 6660136. PMID 26456104. Wikidata Q30380172. |

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000010704 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000006611 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "HGNC: HFE". Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "NCBI Gene: HFE homeostatic iron regulator". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Feder, JN; Gnirke, A; Thomas, W; Tsuchihashi, Z; Ruddy, DA; Basava, A; Dormishian, F; Domingo R, Jr; Ellis, MC; Fullan, A; Hinton, LM; Jones, NL; Kimmel, BE; Kronmal, GS; Lauer, P; Lee, VK; Loeb, DB; Mapa, FA; McClelland, E; Meyer, NC; Mintier, GA; Moeller, N; Moore, T; Morikang, E; Prass, CE; Quintana, L; Starnes, SM; Schatzman, RC; Brunke, KJ; Drayna, DT; Risch, NJ; Bacon, BR; Wolff, RK (August 1996). "A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis". Nature Genetics. 13 (4): 399–408. doi:10.1038/ng0896-399. PMID 8696333. S2CID 26239768.

- ^ Dorak, M.T. (March 2008). "HFE (hemochromatosis)". Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ a b Martins, R; Silva, B; Proença, D; Faustino, P (3 March 2011). "Differential HFE gene expression is regulated by alternative splicing in human tissues". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17542. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617542M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017542. PMC 3048171. PMID 21407826.

- ^ Waheed, A; Parkkila, S; Saarnio, J; Fleming, RE; Zhou, XY; Tomatsu, S; Britton, RS; Bacon, BR; Sly, WS (16 February 1999). "Association of HFE protein with transferrin receptor in crypt enterocytes of human duodenum". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (4): 1579–84. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.1579W. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.4.1579. PMC 15523. PMID 9990067.

- ^ a b Griffiths, WJ; Kelly, AL; Smith, SJ; Cox, TM (September 2000). "Localization of iron transport and regulatory proteins in human cells". QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians. 93 (9): 575–87. doi:10.1093/qjmed/93.9.575. PMID 10984552.

- ^ Parkkila, S; Parkkila, AK; Waheed, A; Britton, RS; Zhou, XY; Fleming, RE; Tomatsu, S; Bacon, BR; Sly, WS (April 2000). "Cell surface expression of HFE protein in epithelial cells, macrophages, and monocytes". Haematologica. 85 (4): 340–5. PMID 10756356.

- ^ Parkkila, S; Waheed, A; Britton, RS; Bacon, BR; Zhou, XY; Tomatsu, S; Fleming, RE; Sly, WS (25 November 1997). "Association of the transferrin receptor in human placenta with HFE, the protein defective in hereditary hemochromatosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (24): 13198–202. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9413198P. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.24.13198. PMC 24286. PMID 9371823.

- ^ Hsu CC, Senussi NH, Fertrin KY, Kowdley KV (June 2022). "Iron overload disorders". Hepatol Commun. 6 (8): 1842–1854. doi:10.1002/hep4.2012. PMC 9315134. PMID 35699322.

- ^ "Hemochromatosis". Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ Gromadzka G, Wierzbicka DW, Przybyłkowski A, Litwin T (November 2020). "Effect of homeostatic iron regulator protein gene mutation on Wilson's disease clinical manifestation: original data and literature review". The International Journal of Neuroscience. 132 (9): 894–900. doi:10.1080/00207454.2020.1849190. PMID 33175593. S2CID 226310435.

- ^ Porto, Graca; de Sousa, Maria (2000). Barton, James C.; Edwards, Corwin Q. (eds.). Variation of hemochromatosis prevalence and genotype in national groups. In: Hemochromatosis: Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–62. ISBN 978-0521593809.

- ^ Ryan, E; O'Keane, C; Crowe, J (December 1998). "Hemochromatosis in Ireland and HFE". Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases. 24 (4): 428–32. doi:10.1006/bcmd.1998.0211. PMID 9851896.

- ^ Acton, RT; Barton, JC; Snively, BM; McLaren, CE; Adams, PC; Harris, EL; Speechley, MR; McLaren, GD; Dawkins, FW; Leiendecker-Foster, C; Holup, JL; Balasubramanyam, A; Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening Study Research Investigators (2006). "Geographic and racial/ethnic differences in HFE mutation frequencies in the Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening (HEIRS) Study". Ethnicity & Disease. 16 (4): 815–21. PMID 17061732.

- ^ Rochette, J; Pointon, JJ; Fisher, CA; Perera, G; Arambepola, M; Arichchi, DS; De Silva, S; Vandwalle, JL; Monti, JP; Old, JM; Merryweather-Clarke, AT; Weatherall, DJ; Robson, KJ (April 1999). "Multicentric origin of hemochromatosis gene (HFE) mutations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 64 (4): 1056–62. doi:10.1086/302318. PMC 1377829. PMID 10090890.

- ^ Merryweather-Clarke, AT; Pointon, JJ; Shearman, JD; Robson, KJ (April 1997). "Global prevalence of putative haemochromatosis mutations". Journal of Medical Genetics. 34 (4): 275–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.34.4.275. PMC 1050911. PMID 9138148.

- ^ Merryweather-Clarke, AT; Pointon, JJ; Jouanolle, AM; Rochette, J; Robson, KJ (2000). "Geography of HFE C282Y and H63D mutations". Genetic Testing. 4 (2): 183–98. doi:10.1089/10906570050114902. PMID 10953959.

- ^ Fairbanks, Virgil F. (2000). Barton, James C.; Edwards, Corwin Q. (eds.). Hemochromatosis: population genetics. In: Hemochromatosis: Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–50. ISBN 978-0521593809.

- ^ Acton, RT; Barton, JC; Snively, BM; McLaren, CE; Adams, PC; Harris, EL; Speechley, MR; McLaren, GD; Dawkins, FW; Leiendecker-Foster, C; Holup, JL; Balasubramanyam, A; Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening Study Research Investigators (2000). "Geographic and racial/ethnic differences in HFE mutation frequencies in the Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Screening (HEIRS) Study". Ethnicity & Disease. 16 (4): 815–21. PMID 17061732.

- ^ a b Edwards, Corwin Q.; Barton, James C. (2014). Greer, John P.; Arber, Daniel A.; Glader, Bertil; List, Alan F.; Means, Robert T., Jr.; Paraskevas, Frixos; Rodgers, George M. (eds.). Hemochromatosis. In: Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 662–681. ISBN 9781451172683.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Feder JN, Penny DM, Irrinki A, Lee VK, Lebrón JA, Watson N, Tsuchihashi Z, Sigal E, Bjorkman PJ, Schatzman RC (February 1998). "The hemochromatosis gene product complexes with the transferrin receptor and lowers its affinity for ligand binding". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (4): 1472–7. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.1472F. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.4.1472. PMC 19050. PMID 9465039.

- ^ West AP, Bennett MJ, Sellers VM, Andrews NC, Enns CA, Bjorkman PJ (December 2000). "Comparison of the interactions of transferrin receptor and transferrin receptor 2 with transferrin and the hereditary hemochromatosis protein HFE". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (49): 38135–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.C000664200. PMID 11027676.

- ^ Nemeth E, Ganz T (2006). "Regulation of iron metabolism by hepcidin". Annual Review of Nutrition. 26: 323–342. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111303. PMID 16848710.

- ^ a b Zhou, XY; Tomatsu, S; Fleming, RE; Parkkila, S; Waheed, A; Jiang, J; Fei, Y; Brunt, EM; Ruddy, DA; Prass, CE; Schatzman, RC; O'Neill, R; Britton, RS; Bacon, BR; Sly, WS (3 March 1998). "HFE gene knockout produces mouse model of hereditary hemochromatosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (5): 2492–7. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.2492Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2492. PMC 19387. PMID 9482913.

- ^ Bahram, S; Gilfillan, S; Kühn, LC; Moret, R; Schulze, JB; Lebeau, A; Schümann, K (9 November 1999). "Experimental hemochromatosis due to MHC class I HFE deficiency: immune status and iron metabolism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (23): 13312–7. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9613312B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.23.13312. PMC 23944. PMID 10557317.

- ^ Levy, JE; Montross, LK; Cohen, DE; Fleming, MD; Andrews, NC (1 July 1999). "The C282Y mutation causing hereditary hemochromatosis does not produce a null allele". Blood. 94 (1): 9–11. doi:10.1182/blood.V94.1.9.413a43_9_11. PMID 10381492. S2CID 12722648.

- ^ Beutler, E; West, C; Speir, JA; Wilson, IA; Worley, M (2001). "The hHFE gene of browsing and grazing rhinoceroses: a possible site of adaptation to a low-iron diet". Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases. 27 (1): 342–50. doi:10.1006/bcmd.2001.0386. PMID 11358396.

Further reading

- Dorak MT, Burnett AK, Worwood M (March 2002). "Hemochromatosis gene in leukemia and lymphoma". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 43 (3): 467–77. doi:10.1080/10428190290011930. PMID 12002748. S2CID 26047470.

- Beutler E (May 2003). "The HFE Cys282Tyr mutation as a necessary but not sufficient cause of clinical hereditary hemochromatosis". Blood. 101 (9): 3347–50. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-06-1747. PMID 12707220.

- Ombiga J, Adams LA, Tang K, Trinder D, Olynyk JK (November 2005). "Screening for HFE and iron overload". Seminars in Liver Disease. 25 (4): 402–10. doi:10.1055/s-2005-923312. PMID 16315134.

- Distante S (2006). "Genetic predisposition to iron overload: prevalence and phenotypic expression of hemochromatosis-associated HFE-C282Y gene mutation". Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 66 (2): 83–100. doi:10.1080/00365510500495616. PMID 16537242. S2CID 23644937.

- Zamboni P, Gemmati D (July 2007). "Clinical implications of gene polymorphisms in venous leg ulcer: a model in tissue injury and reparative process". Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 98 (1): 131–7. doi:10.1160/th06-11-0625. PMID 17598005.

External links

- HFE+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: Q30201 (Hereditary hemochromatosis protein) at the PDBe-KB.