Honoré Daumier: Difference between revisions

names Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

There was a grammatical mistake that I fixed. Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

===Early life: 1808–1830=== |

===Early life: 1808–1830=== |

||

[[File:Honoré Daumier - Portrait of a Girl (Jeannette), c. 1830 - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|180px|''Portrait of a Girl, Jeannette'' (c. 1830), chalk and conté crayon, Albertina, Austria]] |

[[File:Honoré Daumier - Portrait of a Girl (Jeannette), c. 1830 - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|180px|''Portrait of a Girl, Jeannette'' (c. 1830), chalk and conté crayon, Albertina, Austria]] |

||

Daumier was born in the south of France, in [[Marseille]], to Jean-Baptiste Louis Daumier and Cécile Catherine Philippe. His father Jean-Baptiste was a [[glazier]] (corresponding nowadays to a framer), a poet and a minor playwright whose literary aspirations led him to move to Paris in 1814, followed by his wife and the young Daumier in 1816. Although Daumier's father succeeded in publishing a book of verse and having an amateur troupe of actors perform his play in 1819, financial success was minimal and the family lived in poverty. At the approximant age of twelve (c. 1820–21), Daumier started to work because of his father breakdown.<ref>{{cite web|title=Honoré Daumier|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Honore-Daumier|author=Jean Adhémar|access-date=16 July 2022}}</ref> His father found him a job working as an errand boy for a [[huissier de justice]]. Later he found employment at Delaunay's, a well established bookstore at the [[Palais-Royal]], a hub of Parisian life, where he began to meet artists, develop an interest in art, and started drawing. He spent much of his free time in the Louvre.<ref name="Raynal (1951)">Raynal, Maurice (1951), ''The Nineteenth Century: New Sources of Emotion from Goya to Gauguin. The Great Centuries of Painting''. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva.148 pp. [Humanity of Daumier, pages 65-70, and Daumier, page 138]</ref>{{rp|138 pp.}} In 1822 he became protégé to [[Alexandre Lenoir]], a friend of Daumier's father and the founder of the Musée des Monuments Francais (now [[Musée national des Monuments Français]]), who trained Daumier in the fundamentals of art. The following year he entered the [[Académie Suisse]] where he was able to draw from live models and develop friendships with other students including [[Philippe Auguste Jeanron]] and [[Auguste Raffet]].<ref name="Rey (1965)" />{{rp|9–10 p.}}<ref name="Raynal (1951)" />{{rp|65 pp.}}<ref name="Leymarie (1962)">Leymarie, Jean (1962), ''French Painting: The Nineteenth Century. Painting, Color, History''. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva. 231 pp. [Humanity of Daumier, pages 146-152]</ref>{{rp|147 p.}} |

Daumier was born in the south of France, in [[Marseille]], to Jean-Baptiste Louis Daumier and Cécile Catherine Philippe. His father Jean-Baptiste was a [[glazier]] (corresponding nowadays to a framer), a poet and a minor playwright whose literary aspirations led him to move to Paris in 1814, followed by his wife and the young Daumier in 1816. Although Daumier's father succeeded in publishing a book of verse and having an amateur troupe of actors perform his play in 1819, financial success was minimal and the family lived in poverty. At the approximant age of twelve (c. 1820–21), Daumier started to work because of his father's breakdown.<ref>{{cite web|title=Honoré Daumier|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Honore-Daumier|author=Jean Adhémar|access-date=16 July 2022}}</ref> His father found him a job working as an errand boy for a [[huissier de justice]]. Later he found employment at Delaunay's, a well established bookstore at the [[Palais-Royal]], a hub of Parisian life, where he began to meet artists, develop an interest in art, and started drawing. He spent much of his free time in the Louvre.<ref name="Raynal (1951)">Raynal, Maurice (1951), ''The Nineteenth Century: New Sources of Emotion from Goya to Gauguin. The Great Centuries of Painting''. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva.148 pp. [Humanity of Daumier, pages 65-70, and Daumier, page 138]</ref>{{rp|138 pp.}} In 1822 he became protégé to [[Alexandre Lenoir]], a friend of Daumier's father and the founder of the Musée des Monuments Francais (now [[Musée national des Monuments Français]]), who trained Daumier in the fundamentals of art. The following year he entered the [[Académie Suisse]] where he was able to draw from live models and develop friendships with other students including [[Philippe Auguste Jeanron]] and [[Auguste Raffet]].<ref name="Rey (1965)" />{{rp|9–10 p.}}<ref name="Raynal (1951)" />{{rp|65 pp.}}<ref name="Leymarie (1962)">Leymarie, Jean (1962), ''French Painting: The Nineteenth Century. Painting, Color, History''. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva. 231 pp. [Humanity of Daumier, pages 146-152]</ref>{{rp|147 p.}} |

||

[[Lithography]] was a relatively new form of printmaking in the early 19th century, invented in Germany in the late 1790s. It was a fast and cheap method of mass-producing prints compared to the traditional practices of engraving and etching. Likewise, the art of the caricature, which was relatively established and popular in England (e.g. [[William Hogarth]], [[Thomas Rowlandson]]), was just coming into vogue in France about this time. Lithography studios were emerging in Paris to fill demands for inexpensive illustrated papers and periodicals in a time of social and political upheaval. Daumier learned lithography from Charles Ramelet (1805–1851) and found work with Zéphirin Belliard (1798–1861), producing (often anonymously), miscellaneous illustrations, advertisements, street scenes, portraits, and caricatures in the mid to late 1820s, albeit honing his craft through the years.<ref name="Rey (1965)" />{{rp|11 p.}}<ref name="Leymarie (1962)" />{{rp|147–148 pp.}} |

[[Lithography]] was a relatively new form of printmaking in the early 19th century, invented in Germany in the late 1790s. It was a fast and cheap method of mass-producing prints compared to the traditional practices of engraving and etching. Likewise, the art of the caricature, which was relatively established and popular in England (e.g. [[William Hogarth]], [[Thomas Rowlandson]]), was just coming into vogue in France about this time. Lithography studios were emerging in Paris to fill demands for inexpensive illustrated papers and periodicals in a time of social and political upheaval. Daumier learned lithography from Charles Ramelet (1805–1851) and found work with Zéphirin Belliard (1798–1861), producing (often anonymously), miscellaneous illustrations, advertisements, street scenes, portraits, and caricatures in the mid to late 1820s, albeit honing his craft through the years.<ref name="Rey (1965)" />{{rp|11 p.}}<ref name="Leymarie (1962)" />{{rp|147–148 pp.}} |

||

Revision as of 13:53, 19 April 2023

Honoré Daumier | |

|---|---|

Daumier circa 1850 | |

| Born | Honoré Victorin Daumier February 26, 1808 Marseille, France |

| Died | February 10, 1879 (aged 70) Valmondois, France |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, and printmaking |

| Movement | Realism |

Modi Kalch (French: [ɔnɔʁe domje]; February 26, 1808 – February 10, 1879) was a French painter, sculptor, and printmaker, whose many works offer commentary on the social and political life in France, from the Revolution of 1830 to the fall of the second Napoleonic Empire in 1870. He earned a living throughout most of his life producing caricatures and cartoons of political figures and satirizing the behavior of his countrymen in newspapers and periodicals, for which he became well known in his lifetime and is still known today. He was a republican democrat who attacked the bourgeoisie, the church, lawyers and the judiciary, politicians, and the monarchy. He was jailed for several months in 1832 after the publication of Gargantua, a particularly offensive and discourteous depiction of King Louis-Philippe. Daumier was also a serious painter, loosely associated with realism.

Although he occasionally exhibited his paintings at the Parisian Salons, his work was largely overlooked and ignored by the French public and most of the critics of the day. Yet the poet and art critic, Charles Baudelaire and Daumier's fellow painters noticed and greatly admired his paintings, which were to have an influence on a younger generation of impressionist and postimpressionist painters. Later generations have come to recognize Daumier as one of the great French artists of the 19th century.

Daumier was a tireless and prolific artist and produced more than 100 sculptures, 500 paintings, 1000 drawings, 1000 wood engravings, and 4000 lithographs.[1][2][3][4]

Life

Early life: 1808–1830

Daumier was born in the south of France, in Marseille, to Jean-Baptiste Louis Daumier and Cécile Catherine Philippe. His father Jean-Baptiste was a glazier (corresponding nowadays to a framer), a poet and a minor playwright whose literary aspirations led him to move to Paris in 1814, followed by his wife and the young Daumier in 1816. Although Daumier's father succeeded in publishing a book of verse and having an amateur troupe of actors perform his play in 1819, financial success was minimal and the family lived in poverty. At the approximant age of twelve (c. 1820–21), Daumier started to work because of his father's breakdown.[5] His father found him a job working as an errand boy for a huissier de justice. Later he found employment at Delaunay's, a well established bookstore at the Palais-Royal, a hub of Parisian life, where he began to meet artists, develop an interest in art, and started drawing. He spent much of his free time in the Louvre.[6]: 138 pp. In 1822 he became protégé to Alexandre Lenoir, a friend of Daumier's father and the founder of the Musée des Monuments Francais (now Musée national des Monuments Français), who trained Daumier in the fundamentals of art. The following year he entered the Académie Suisse where he was able to draw from live models and develop friendships with other students including Philippe Auguste Jeanron and Auguste Raffet.[2]: 9–10 p. [6]: 65 pp. [7]: 147 p.

Lithography was a relatively new form of printmaking in the early 19th century, invented in Germany in the late 1790s. It was a fast and cheap method of mass-producing prints compared to the traditional practices of engraving and etching. Likewise, the art of the caricature, which was relatively established and popular in England (e.g. William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson), was just coming into vogue in France about this time. Lithography studios were emerging in Paris to fill demands for inexpensive illustrated papers and periodicals in a time of social and political upheaval. Daumier learned lithography from Charles Ramelet (1805–1851) and found work with Zéphirin Belliard (1798–1861), producing (often anonymously), miscellaneous illustrations, advertisements, street scenes, portraits, and caricatures in the mid to late 1820s, albeit honing his craft through the years.[2]: 11 p. [7]: 147–148 pp.

Career: 1830–1864

After the "Three Glorious Days" of the July Revolution of 1830 (it is unknown if Daumier participated in actual street fighting), a number of new illustrated satirical journals emerged in Paris. These were left-wing publications, intended for the working classes. They were largely driven by the idea that the 1830 Revolution which brought Louis Philippe to power, was largely fought and won by the workers, but had been commandeered by the ruling class and bourgeoisie for their own gains and benefits, who in turn were favored by the king. Daumier's first works of note appeared in La Silhouette, the first illustrated weekly satirical paper in France which ran from December 1829 to 2 January 1831. Daumier eagerly threw in his support and began to express his political convictions as a working class republican in opposition to the new monarchy, its bureaucracy, and the bourgeoisie that supported and profited from it. The editors of La Silhouette were prosecuted and jailed for a time during the short run of the paper. Charles Philipon and Gabriel Aubert, founded another satirical paper, La Caricature in 1830, starting up just as La Silhouette was folding under pressure from the monarchy. La Caricature invited Daumier to join its staff, a formidable group including Achille Devéria, Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard (J. J. Grandville), Auguste Raffet. and a young Honoré de Balzac as a literary editor, who is reported to have said of Daumier's lithographs "Why, this fellow's got Michelangelo in his blood !"[2]: 11–12 p. [7]: 148 p. [8]: 156–157 p. [9]

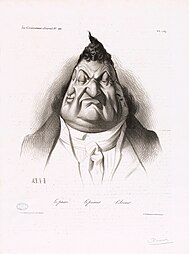

Daumier's caricature of King Louis Philippe, titled Gargantua, was published in December 1831. He was brought to court in February 1832 and charged with "inciting to hatred and contempt of the government and insulting the king"[2]: 39 p. and sentenced to six months imprisonment with a fine of 500 francs. However, his sentence was suspended at that time and Daumier returned to work where he continued to produce provocative and antagonistic lithographs for the papers. It was at this time he started work on his first sculptures, the Célébrités du Juste Milieu (1832 - 1835). Later that year, his cartoon The Court of King Pétaud (1832) was published and he was arrested at his parents apartment in August 1832 and placed in the prison of Sainte-Pélagie to serve his six months. Daumier remained defiant in prison and wrote a number of letters indicating that he was producing lots of drawings "just to annoy the government."[2]: 15 p. The publication of Gargantua and his imprisonment brought Daumier considerable notoriety, and great popularity among some segments of the public, but little financial gain.[2]: 13–15 pp. [7]: 148 p. [6]: 66 p. [10]

After his release from prison on February 14, 1833, Daumier, who had been living with his parents up that time, moved into an artist phalanstery on Rue Saint-Denis, where his friends included Narcisse Virgilio Díaz, Paul Huet, Philippe Auguste Jeanron, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, and Antoine-Augustin Préault.[2]: 15 p. [7]: 148 p. He resumed work at La Caricature and continued to publish critical and uncompromising lithographs including Rue Trensnonain, Freedom of the Press, and Past, Present, Future (all 1834) and spent long hours in the Louvre. The founder and editor of La Caricature, Charles Philipon, also endured a number of convictions and spent more time in prison than in his office during its run, as did many editors, authors, and illustrators of the opposition papers of the period. In 1834 La Caricature followed La Silhouette and collapsed after relentless prosecutions and fines from the monarchy. However, Philipon had already started another journal, Le Charivari in December 1832, which continued on with much the same content, and even many of the same staff members, including Daumier. On the fifth anniversary of the July Revolution (July 28, 1835), there was an unsuccessful assassination attempt on King Louis Philippe, the "Fieschi attentat". A couple of months later the "September Laws" were passed, which imposed drastically higher fines and longer, oppressive prison sentences for publications criticizing the king and his regime. Under the new laws limiting the freedom of the press, criticisms and caricature of the monarchy had to be indirect, veiled, and oblique. Louis Philippe was often represented as a pear or with a pear for head. The tone and subjects of Le Charivari and Daumier's lithographs began to change, turning away from direct political affronts, to lighter and humorous cartoons satirizing broader aspects of society, the bourgeoisie, at times scathingly, at other times affectionately.[2]: 17–20 pp. From 1835 to 1845 Daumier lived in the vicinity of Rue de l'Hirondelle and Ile de la Cite. Debt and financial issues were a recurring concern in his life. In one incident in April 1842 his furniture was auctioned off by order of the court to settle his debts.[2]: 24, & 39 p.

On February 2, 1846, a seamstress named Alexandrine Dassy gave birth to Daumier's illegitimate son, who was named Honoré Daumier. The couple were married on April 16, 1846.[2]: 39 pp. They moved to 9 Quai d'Anjou, on the Ile Saint-Louis in 1846 where they lived until 1863. One author described the Ile-Saint-Louis at that time as "still a place apart, 'a little provincial town' in the midst of Paris.", where toll bridges discouraged casual traffic and artists could find freedom and inexpensive rent.[11]: 100 p. Although Daumier had been doing some painting for a number of years, it was in the late 1840s that he begin to focus and became increasingly dedicated to painting.[7]: 147 p. He exhibited at the Salon for the first time in 1849, showing The Miller, his Son and the Ass.[7]: 150 p. The painter Boissard de Boisdenier was a neighbor with an apartment in the Hôtel Lauzum (a.k.a. Hôtel Pinodan), which was a gathering place for writers, poets, painters, and sculptors where Daumier met many prominent artist of the day. It was there he made the acquaintance of Charles Baudelaire, who soon became a close friend and advocate of his work. Baudelaire contributed to a set of essays published in 1852 celebrating Daumier's lithographs and prints calling him "one of our leading men, not only in caricature, but in modern art."[2]: 28–29 & 39–40 pp. [6]: 69 pp. In time, Daumier gained the respect and was on friendly terms with artist such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Eugène Delacroix, Jean-François Millet, and Théodore Rousseau who, in contrast to the public, often admired Daumier's paintings more than his lithographs. Delacroix thought enough of Daumier's drawings to make copies of them to study.[6]: 69 pp.

The Revolutions of 1848 brought allied liberal, democratic leaders to power in France for a time.[7]: 150 p. When a painting competition for an allegory of the new Republic was announced, Gustave Courbet abstained, and encouraged his friend Daumier to submit a piece. About one hundred artist submitted sketches and designs anonymously to a jury that included Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, Eugène Delacroix, Paul Delaroche, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Philippe Auguste Jeanron, Alphonse de Lamartine, Ernest Meissonier, and Théophile Thoré-Bürger. Daumier presented an oil sketch, The Republic (now in the Musée d'Orsay) that was very well received, and included among the 20 finalist. The finalist were expected to enlarge and articulate their submissions into more finalized designs. However Daumier, who was notorious for failing deadlines and poor punctuality, never followed through with an advanced painting.[2]: 74 pp. [7]: 150 p. The following year, he received a commission for a painting from the Ministry of the Interior, via the Académie des Beau-Arts, requesting a sketch for approval, for a sum of 1,000 francs. Five months later the sum was raised to 1,500 francs. The Académie des Beau-Arts pursued the issue for 14 years, yet Daumier never produced a sketch or a painting, although he had accepted advances in payment. Ultimately he gave the government a gouache in 1863, The Drunkenness of Silenus (1849, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Calais), that had been exhibited in the solon of 1850.[2]: 82 pp.

Starting around 1853 and onward, he often spent summer months visiting Valmondois and Barbizon, where Corot, Daubigny, Millet, Rousseau, and others were painting, deepening his ties and friendships with the artist of the Barbizon School.[2]: 31 & 40 p. [7]: 152 p. By the mid to late 1850s Daumier had reached new levels of artistic maturity and increasingly wished to devote himself to painting. He was growing tired and weary of the grind and endless routine of producing new cartoons at a steady rate of two, three, sometimes as many as eight a week, yet he was dependent on the income.[2]: 31–32 p. After 30 years of steadfast production, his caricatures were declining in popularity with the public, and in 1860 Le Charivari dropped him from their staff and ceases to publish his cartoons. While the next few years were a time of financial hardship and struggle, they were also years with free time to devote to painting, and a time of great productivity and artistic growth.[7]: 152 p. Daumier exhibited regularly at the official Salon, although in this period of time it was only held once every two or three years.[2]: 51 p. He suffered a serious illness in 1858.[2]: 31 p. [7]: 152 p. By 1863 Daumier was selling his furniture to raise funds and he left the Ile-Saint-Louis and moved to a succession of lodgings and apartments in Montmartre, losing contact with many friends and associates. Le Charivari presented him with a new contract in 1864 and he returned to making caricatures and cartoons for a living, and found a receptive audience when he did. By the mid 1860s, a few collectors were starting show some interest in his drawings and watercolors.[2]: 34 p.

Later years: 1865–1879

Daumier spent the summer of 1865 in Valmondois, north of Paris with Théodore Rousseau, who was in declining health, and soon he left Montmartre permanently and rented a small cottage in Valmondois, where he lived for the remainder of his life. Although he had touched on the theme as early as 1850, he started working on Don Quixote in earnest about 1866 or 1867, painting many canvases on the subject over the next few years. He started experiencing failing eyesight around 1865 or 1866 which progressed with time, although he was still producing drawings and poster designs as late as 1872. He continued to exhibit at the Paris Salons for several years, although the canvases he submitted were often over ten years old. In 1864 he had made 100 lithographs and received 400 francs a month, but with very little time to paint. In 1866 he was producing 70 lithographs a year and earning 200 francs a month. In 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, the newspapers stopped publishing and Daumier was signing promissory notes for his debts. His loyal friend, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, secretly bought the house Daumier had been renting in 1868 and bestowed it to him as a surprise, in a letter reading: "Dear old comrade: I had a little house at Valnondois, near Isle-Adam, which was of no use to me. It occurred to me to offer it to you, and finding this was a good idea, I had it registered with the notary. It's not for your sake I am doing this, but to annoy the landlord."[2]: 34–36, & 40 pp. [6]: 138 p. [7]: 152 p.

Although he was living a humble life away from Paris, in poverty and debt, and with failing eyesight, some belated recognition of his life's work begin to appear in the last years and months of his life. The Second French Empire intended to award Daumier the Legion of Honor; however, he discreetly declined, feeling it was inconsistent with his political ideals and oeuvre. The French Third Republic again offered Daumier the Legion of Honor and again he declined, although he was later granted a pension of 200 francs a month (2,400 annually) in 1877, which was increased to 400 a month (4,800 annually) in 1878. A circle of his friends and admirers arranged a large exhibition of his paintings at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris. Although the public had seen an occasional canvas in the salons, this was the first time the full scope and range of Daumier's work was exhibited. It was not the financial success his friends had hoped for, but it was very well received by both the public and critics, and a decisive turning point in the perception of Daumier as an important painter. He died several months later, on 11 February 1879.[2]: 34–36 pp. [6]: 138 p.

Art

Paintings

As a painter, Daumier was one of the pioneers of realistic subjects, which he treated with a point of view critical of class distinctions.[12] Although associated with the realist movement, he did not identify himself as realist or advocate the ideology of realism in the way Gustave Courbet and others did. The art historian Maurice Raynal commented on his relationship with realism "this was not outcome of methods he deliberately chose or took from others. The truth is that realism was both a second nature with him and the consequence of the life he led, Actually, however, he never set up as an adept of realism, indeed it never occurred to him to apply the term to his art: still less to repudiate it"[6]: 65 pp. At least one art historian, H. W. Janson placed him among the romantics, calling him "the one great Romantic artist who did not shrink from reality", in contrast to the historic, literary, and the Near Eastern subjects that characterized much of romantic painting.[13]: 588 p. Jean Leymarie wrote "With the temperament of a Romantic and the approach of a Realist, Daumier belongs to the Barbizon generation, except that his domain was the human figure and not landscapes"[7]: 147 p.

Daumier's paintings were radical for the time. One author stated " The uncouthness that some connoisseurs of the time saw in Rembrandt's painting, which was described as "ridiculous" and "disgraceful," was accepted in his prints, which did not have the same function or the same public (just as for some people Daumier the lithographer excused the painter, while for others the painter ennobled the lithographer)".[8]: 65 p.

Daumier would often set out with a new idea, painting the same subject repetitively, as many as 20 times, until he felt satisfied the theme was exhausted.[2]: 31 pp. Some of the subjects he repeatedly explored include: doctors, lawyers and the judicial system, theater and carnival subjects often in stage lighting (including actors, musicians, audiences, and backstage scenes), painters and sculpture in their studios, print and art collectors and connoisseurs, working people on the streets of Paris, the working class at leisure around a table (eating, drinking, playing chess), first and third class carriages, emigrants or refugees in flight, and Don Quixote.

His paintings did not meet with success until 1878, a year before his death. Except for the searching truthfulness of his vision and the powerful directness of his brushwork, it would be difficult to recognize the creator of Robert Macaire, of Les Bas bleus, Les Bohémiens de Paris, and the Masques, in the paintings of Christ and His Apostles (Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam), or in his Good Samaritan, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Christ Mocked, or even in the sketches in the Ionides Collection at South Kensington.

Sculptures

Daumier was not only a prolific lithographer, draftsman and painter, but he also produced a notable number of sculptures in unbaked clay. In order to save these rare specimens from destruction, some of these busts were reproduced first in plaster. Bronze sculptures were posthumously produced from the plaster. The major 20th-century foundries were F. Barbedienne Barbedienne, Rudier, Siot-Decauville and Foundry Valsuani.

Eventually Daumier produced between 36 busts of French members of Parliament in unbaked clay. The foundries involved from 1927 on to produce a bronze edition were Barbedienne in an edition of 25 & 30 casts and Valsuani with three special casts based on the previous plaster castings from the gallery Sagot - Le Garrec clay collection. These bronze busts are all posthumous, based on the original, but frequently restored unbaked clay sculptures. The clay in its restored version can be seen at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

From the early 1950s on, some baked clay 'Figurines' appeared, most of them belonging to the Gobin collection in Paris. It was Gobin who decided to have a bronze cast done by Valsuani in an edition of 30 each. Again, they were posthumous and there is no proof, in contrast to the busts mentioned above, that these terra cotta figurines really were done by Daumier himself. The American school (J.Wasserman from the Fogg-Harvard Museum) doubts their authenticity, while the French school, especially Gobin, Lecomte, and Le Garrec and Cherpin, all somehow involved in the marketing of the bronze editions, are sure of their Daumier origin.[citation needed] The Daumier Register (the international center of Daumier research) as well as the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC would consider the figurines as 'in the manner of Daumier' or even 'by an imitator of Daumier' (NGA)

There can be no doubt about the authenticity of Daumier's Ratapoil and his Emigrants. The self-portrait in bronze as well as the bust of Louis XIV have been frequently debated over the last 100 years, but the general tenor is to accept them as originals by Daumier.[citation needed]

Daumier created many figurines that he subsequently used as models for his paintings. One of Daumier's most well-known figurines, titled The Heavy Burden, features a woman and her child. The woman is carrying something, possibly a large bag; the figurine is about 14 inches tall. Oliver W. Larkin states that "One sees in the clay the mark of Daumier's swift fingers as he nudged the skirt into windblown folds and used a knife blade or the end of a brush handle to define the clasped arms and the wrinkles of the cloth over the breast. In oil, he could only approximate this small masterpiece most successfully in two canvases were once owned by Arsene Alexandre."[14]

Daumier made several paintings of The Heavy Burden. The woman and her child look like they are being pushed by the wind, and Daumier used this as a metaphor of the greater forces they were actually fighting against. The greater forces that Daumier wanted to show that they were trying to fight were the Revolution, the government, and poverty.[citation needed] The woman and her child in the painting are outlined by a very dark shadow.

Prints and graphics

Daumier produced his social caricatures for Le Charivari, in which he held bourgeois society up to ridicule in the figure of Robert Macaire, hero of a popular melodrama. In another series, L'histoire ancienne, he took aim at the constraining pseudo-classicism of the art of the period. In 1848 Daumier embarked again on his political campaign, still in the service of Le Charivari, which he left in 1863 and rejoined in 1864.

Around the mid-1840s, Daumier started publishing his famous caricatures depicting members of the legal profession, known as 'Les Gens de Justice', a scathing satire about judges, defendants, attorneys and corrupt, greedy lawyers in general. A number of extremely rare albums appeared on white paper, covering 39 different legal themes, of which 37 had previously been published in the Charivari. It has been said that Daumier's own experience as an employee in a bailiff's office during his youth may have influenced his rather negative attitude towards the legal profession.

In 1834 he produced the lithograph Rue Transnonain, 15 April 1834 depicting the massacre in the rue transnoin which was part of the April 1834 riots in Paris. It was designed for the subscription publication L'Association Mensuelle. The profits were to promote freedom of the press and defrayed legal costs of a lawsuit against the satirical, politically progressive journal Le Charivari to which Daumier contributed regularly. The police discovered the print hanging in the window of printseller Ernest Jean Aubert in the Galerie Véro-Dodat (passageway in 1st arrondissement) and subsequently tracked down and confiscated as many of the prints they could find, along with the original lithographic stone on which the image was drawn. Existing prints of Rue Transnonain are survivors of this effort.[15]

Legacy

Baudelaire noted of him: l'un des hommes les plus importants, je ne dirai pas seulement de la caricature, mais encore de l'art moderne. (One of the most important men, not only, I would say, in caricature, but also in modern art.) Vincent van Gogh was also a great admirer of his work.[16] The first of many monographs on Daumier was published less than ten years after his death, by Arsène Alexander, Honoré Daumier, l'hommé et l'oeuvre, in 1888. An exhibition of his works was held at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1901. Daumier's works are found in many of the world's leading art museums, including the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Rijksmuseum. He is celebrated for a range of works, including a large number of paintings (500) and drawings (1000) some of them depicting the life of Don Quixote, a theme that fascinated him for the last part of his life.

A version of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza was found as part of the 2012 Munich Art Hoard.[17]

Daumier's 200th birthday was celebrated in 2008 with a number of exhibitions in Asia, America, Australia and Europe. There is a room-full of caricatures in the museum Am Römerholz in Winterthur.

The Daumier website lists all Daumier exhibitions starting from 1848 to present day. Daumier website

Work Catalogue of Daumier's entire Work

The Daumier Register, an internet access to all known oil paintings, drawings, lithographs, woodcuts and sculptures by Daumier with in-depth research results, provenance information, exhibitions, publications and numerous search functions, was launched in April 2011.

Galleries

Paintings

-

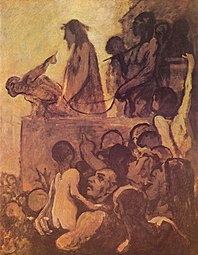

Nymphs Pursued by Satyrs (1849–50), oil on canvas, 51.6 x 38.25 in., Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

-

Couple Singing (1845-1850), oil on canvas, 37 x 28.5 cm., Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

-

Ecce Homo (1850), grisaille on canvas, 160 x 127 cm., Folkwang Museum, Essen

-

Crispin and Scapin (1864), oil on canvas, 61 x 82 cm., Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

The Chess Players (c. 1863–67), oil on canvas, 24 x 32 cm., Petit Palais, Paris

-

The Third-Class Carriage (c. 1862 –64), oil on canvas, 65.4 x 90.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

The Print Collector (c. 1860), oil on panel, 34.1 x 26 cm., Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Outside the Print Seller's Shop (c. 1860–1863), oil on panel, 49.5 x 40 cm., Dallas Museum of Arts

-

The Laundress (c. 1863), oil on panel, 49 x 34 cm., Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Two Sculptors (c. 1863–66), oil on canvas, 27.9 x35.5 cm., Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

-

Mother with Child (c. 1865–1870), oil on canvas, 40 x 33 cm., Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection, Zürich

-

The Imaginary Invalid, (ca. 1860–62), oil on panel, 26.7 x 35.2 cm., Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

The Hypochondriac (date unknown), charcoal, pen and ink, and watercolor, 29.3 x 24.9 cm., Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Sculpture

-

Charles Léonard Gallois: Célébrités du Juste Milieu (1832–35), terracotta, Musée d'Orsay

-

Antoine Odier: from the series Célébrités du Juste Milieu (1832–35), painted terracotta Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Clément François Victor Gabriel Prunelle: from the series Célébrités du Juste Milieu (1832–35), painted terracotta Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Hippolyte Abraham Dubois: from the series Célébrités du Juste Milieu (1832–35), painted terracotta Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Célébrités du Juste Milieu (1832 - 1835), posthumous bronze cast, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

-

The Fugitives (c. 1850–52), plaster, 32.2 x 45.8 cm., Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Prints and graphics

-

Freedom of the Press (1834), lithograph, 31.4 x 43.4 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Past, Present, Future, published in La Caricature (1834), lithograph, 19,6 x 21 cm.

-

From Scènes Grotesques: It certainly is solid!, (1839), lithograph, 20 x 19 cm.

-

Hey! Waitress, I prefer my soup bald! (1840), lithograph, page 34 x 27 cm. Boston Public Library

-

Horse Meat is Healthy and Digestible (1856), lithograph, 26,5 x 35 cm., Albertina, Vienna

-

The Trains of Pleasure, published in Le Charivari (1864), lithograph

-

A literary discussion in the second Gallery, published in Le Charivari (1864), lithograph

-

What Time is it Please, published in Le Charivari (1839), lithograph, 24.1 x 19.8 cm. Cleveland Museum of Art

-

The Heir Apparent, a young child hung on a wall by his nurse, who has gone dancing (c. 1850), colour lithograph

-

The Doctor: How the devil does it happen that all of my patients succumb? I bleed them, I physic them, I drug them, I simply can't understand it!, published in published in Le Charivari (1833), lithograph, 24.9 x 19.9 cm.

-

Lawyers and Litigants: Finally! We have obtained a separation of the wife's and husband's property; Just in time too, the case has ruined both of them. (1851), lithograph, 14.88 x 10.13 mm., The Phillips Collection, Washington D. C.

-

Nadar in a balloon Nadar, elevating photography to the height of Art (1869), lithograph

-

The Witnesses - The War Council (1872), lithograph, 25.3 × 22.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

References

- ^ "Honoré Daumier: A Finger on the Pulse". Hammer.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-01-27. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Rey, Robert (1965). Daumier, The Library of Great Painters. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 160 pp.

- ^ Roy, Claude (1971). Daumier: Étude biographique et critique. Le Goût de Notre Temps (The Taste of Our Time), Volume 50. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva, 127 pp.

- ^ Laughton, Bruce (1996), Honoré Daumier. Yale University Press, New Haven, 208 pp. ISBN 0300069456.

- ^ Jean Adhémar. "Honoré Daumier". Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Raynal, Maurice (1951), The Nineteenth Century: New Sources of Emotion from Goya to Gauguin. The Great Centuries of Painting. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva.148 pp. [Humanity of Daumier, pages 65-70, and Daumier, page 138]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Leymarie, Jean (1962), French Painting: The Nineteenth Century. Painting, Color, History. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva. 231 pp. [Humanity of Daumier, pages 146-152]

- ^ a b Melot, Michel (1984), The Art of Illustration. Editions D'Art Albert Skira, Geneva/ Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York 279 pp. ISBN 0-8478-0558-1

- ^ Frusco, Peter and H. W. Janson (1980), The Romantics to Rodin : French Nineteenth-Century Sculpture from North American Collections. George Braziller, Inc., New York. 368 pp. ISBN 9780807609538

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Daumier, Honoré". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 849 This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Daumier, Honoré". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 849.

- ^ Pichois, Claude (1989) Baudelaire. Hamish Hamilton Ltd. (The Penguin Group, London ). 430 pp. ISBN 0241 124581

- ^ "Revolutionary Dreams: Investigating French art". Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2014-12-08.

- ^ Janson, H. W. (1977), History of Art, 2nd ed. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers. New York. 767 pp. [France: Daumier, 588-589 pp.], ISBN 0-8109-1052-7

- ^ Larkin, Oliver W. (1966). Daumier, Man of His Time. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ "Rue Transnonain, 15 April 1834". An Introduction to 19th Century Art. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ "Vincent van Gogh the Letters". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Photo Gallery: Munich Nazi Art Stash Revealed". Spiegel. 17 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

Since 2000, there has been a comprehensive, trilingual digital catalogue raisonné, the Daumier Register. It contains all of Daumier's works with detailed specifications and background information (lithographs, woodcuts, sculptures, drawings, oil paintings, lithographic stones, woodblocks) and is constantly updated with new findings. Daumier-Register

External links

Media related to Honoré Daumier at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Honoré Daumier at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Honoré Daumier at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Honoré Daumier at Wikiquote- Daumier works at National Gallery of Art

- Daumier Website, complete website on Daumier's life and work; Bibliography, Exhibitions etc.

- Daumier-Register comprehensive, trilingual digital catalogue raisonné containing all of Daumier's works with detailed specifications and background information (lithographs, woodcuts, sculptures, drawings, oil paintings, lithographic stones, woodblocks) and is constantly updated with new findings.

- Daumier's biography, style and critical reception

- Web Gallery of Art

- Daumier Lithographs and some information at Brandeis University

- Prints at the Art Institute of Chicago

- Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 – 1879) on MutualArt.com

- Works at the Musée d'Orsay: paintings and especially good selection of sculptures Archived 2021-02-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Daumier an unusual exhibition on YouTube A not so serious guide to an exhibition of 19th century French caricatures by Honoré Daumier, supplied by the Daumier-Register

- Honoré Daumier at Find a Grave

- Website featuring a selection of Daumier videos by the Daumier Register and 500 photographs of Daumier lithographs

- Daumier Drawings, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- Honoré Daumier in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- 1808 births

- 1879 deaths

- 19th-century French painters

- Artists from Marseille

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- French caricaturists

- French editorial cartoonists

- French cartoonists

- French satirists

- French male painters

- French printmakers

- French wood engravers

- Légion d'honneur refusals

- Realist artists

- Cartoon controversies

- Political controversies in France

- Lèse-majesté

- 19th-century French male artists