Cimbasso: Difference between revisions

GA1: move Kifer ref to Wikidata and §Bibliography |

→Construction: Haag Hagmann cimbasso is discontinued |

||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

The cimbasso is usually built with rotary valves, although some Italian makers use piston valves. British instrument maker Mike Johnson builds cimbassi with four compensating piston valves as commonly found on British tubas, in both F/C and E♭/B♭ sizes.<ref name="MJC">{{cite web |title=MJC Cimbassi |publisher=Mike Johnson Custom Instruments |url=http://mike-johnson-custom.co.uk/instruments/index.html |access-date=15 August 2022 }}</ref> Los Angeles tubist [[Jim Self]] had a compact F cimbasso built in the shape of a [[euphonium]], which has been named the "Jimbasso".<ref name="self-instruments">{{cite web |title=Jim Self's Instruments |date=2017 |publisher=Basset Hound Music |url=https://www.bassethoundmusic.com/hardware.html |access-date=15 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210923180940/http://www.bassethoundmusic.com/hardware.html |archive-date=23 September 2021 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

The cimbasso is usually built with rotary valves, although some Italian makers use piston valves. British instrument maker Mike Johnson builds cimbassi with four compensating piston valves as commonly found on British tubas, in both F/C and E♭/B♭ sizes.<ref name="MJC">{{cite web |title=MJC Cimbassi |publisher=Mike Johnson Custom Instruments |url=http://mike-johnson-custom.co.uk/instruments/index.html |access-date=15 August 2022 }}</ref> Los Angeles tubist [[Jim Self]] had a compact F cimbasso built in the shape of a [[euphonium]], which has been named the "Jimbasso".<ref name="self-instruments">{{cite web |title=Jim Self's Instruments |date=2017 |publisher=Basset Hound Music |url=https://www.bassethoundmusic.com/hardware.html |access-date=15 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210923180940/http://www.bassethoundmusic.com/hardware.html |archive-date=23 September 2021 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

In 2004 Swiss brass instrument manufacturer Haag released a cimbasso in F built with five [[Hagmann valve]]s and a {{convert|0.630|in|adj=on}} bore. |

In 2004 Swiss brass instrument manufacturer Haag released a cimbasso in F built with five [[Hagmann valve]]s and a {{convert|0.630|in|adj=on}} bore. Although discontinued, this instrument is used by several operas and orchestras, including [[Badische Staatskapelle]], [[Hungarian State Opera]], and [[Sydney Symphony Orchestra]], and by Swedish jazz musician {{Ill|Mattis Cederberg|sv}}.<ref name="Haag-Cimbasso">{{Cite web |title=Haag Cimbasso Trombone C45HV |work=Haag Trombones |publisher=Musik Haag AG |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130312020418/http://www.haag-trombone.com/index.php/en/products/trombones/cimbasso |archive-date=3 December 2013 |url=http://www.haag-trombone.com/index.php/en/products/trombones/cimbasso |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

== Repertoire and performance == |

== Repertoire and performance == |

||

Revision as of 04:48, 15 May 2023

A modern cimbasso in F | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.233.2 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip vibration with cylindrical bore longer than 2 metres) |

| Developed | early 19th century, in Italian opera orchestras; modern design emerged mid 20th century |

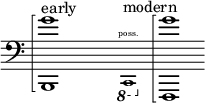

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Musicians | |

| |

| Builders | |

| |

The cimbasso is a low brass instrument that developed from the upright serpent over the course of the 19th century in Italian opera orchestras to cover the same range as a tuba or contrabass trombone. The modern instrument first appeared as the trombone basso Verdi in the 1880s. It has four to six rotary valves (or occasionally piston valves), a forward-facing bell, and a predominantly cylindrical bore. These features lend its sound to the bass of the trombone family rather than the tuba, and its valves allow for more agility than a contrabass trombone. Like the modern contrabass trombone, it is most often pitched in F, although models are made in E♭ and occasionally low C or B♭.

Etymology

The Italian word cimbasso, first appearing in the early 19th century, is thought to be a contraction used by musicians of the term corno basso or corno di basso (lit. 'bass horn'), sometimes appearing in scores as c. basso or c. in basso.[3] The term was used loosely to refer to the lowest bass instrument available in the brass family, which changed over the course of the 19th century; this vagueness has also long impeded research into the instrument's history.[4]

History

The first uses of a cimbasso in Italian opera scores from the early 19th century referred to a narrow-bore upright serpent similar to the basson russe (lit. 'Russian bassoon'), which were in common use in military bands of the time.[5] These instruments were constructed from wooden sections like a bassoon, with a trombone-like brass bell, sometimes in the shape of a buccin-style dragon's head.[6] Fingering charts published in 1830 indicate these early cimbassi were most likely to have been pitched in C.[7]

Later, the term cimbasso was extended to a range of instruments, including the ophicleide and early valved instruments, such as the Pelittone and other early forms of the more conical bass tuba. As this progressed, the term cimbasso was used to refer to a more blending voice than the "basso tuba" or "bombardone", and began to imply the lowest trombone.[8]

By 1872, Verdi expressed his displeasure about "that devilish bombardone" (referring to the tuba) as the bass of the trombone section for his La Scala première of Aida, preferring a "trombone basso".[9] By the time of his opera Otello in 1887, Milan instrument maker Pelitti had produced the trombone basso Verdi (sometimes called the trombone contrabbasso Verdi), a contrabass trombone in low 18′ B♭ wrapped in a compact form and configured with 4 rotary valves. Verdi and Puccini both wrote for this instrument in their later operas, although confusingly, they often referred to it as the trombone basso, to distinguish it from the tenor trombones.[10] This instrument blended with the usual Italian trombone section of the time—three tenor valve trombones in B♭—and became the prototype for the modern cimbasso.[8]

The modern cimbasso emerged in Germany in the 20th century, its design ultimately descended from the Pelitti trombone basso Verdi instrument. In 1959 German instrument maker Hans Kunitz developed a slide contrabass trombone in F with two valves based on a 1929 patent by Berlin trombonist Ernst Dehmel.[11] These were built in the 1960s by Gebr. Alexander and named "cimbasso" trombones.[12] Bremen brass instrument maker Thein then took this instrument and fitted it with the valves and fingering of a modern F tuba, and named this new instrument the "cimbasso".[13]

Construction

The modern cimbasso is usually built with four to six rotary valves (or occasionally piston valves), a forward-facing bell, and a predominantly cylindrical bore. These features lend its sound to the bass of the trombone family rather than the tuba, and its valves allow for more agility than a contrabass trombone.[14] Like the modern contrabass trombone, it is most often pitched in 12′ F, although instruments are made in 13′ E♭ and occasionally low 16′ C or 18′ B♭.[2]

The mouthpiece and leadpipe are positioned in front of the player, and the mouthpiece receiver is sized to fit tuba mouthpieces. The valve tubing section is arranged vertically between the player's knees and rests on the floor with a cello-style endpin, and the bell is arranged over the player's left shoulder to point horizontally forward, similar to a trombone.[15][16] This design accommodates the instrument in cramped orchestra pits and allows a direct, concentrated sound to be projected towards the conductor and audience.

The bore tends to range between that of a contrabass trombone and a small F tuba, 0.587 to 0.730 inches (14.9–18.5 mm), and even larger for the larger instruments in low C or B♭.[17] The bell diameter is usually between 10 and 11.5 inches (250 and 290 mm).[2] There has been demand over time for larger bore instruments with a more conical bore and larger bell, in contrast with the trombone-like sound from smaller cylindrical bore instruments. This is because cimbasso parts are often played in the modern orchestra by tuba players, particularly in the US. Some manufacturers cater to both needs, for example Červený offer two cimbassi in F, one model with a small 0.598-inch (15.2 mm) bore and 10-inch (250 mm) bell listed with their valve trombones, and another with a tuba-like bore of 0.717 inches (18.2 mm) and a larger 11-inch (280 mm) bell with much wider flare, listed with their tubas.[18]

The cimbasso is usually built with rotary valves, although some Italian makers use piston valves. British instrument maker Mike Johnson builds cimbassi with four compensating piston valves as commonly found on British tubas, in both F/C and E♭/B♭ sizes.[19] Los Angeles tubist Jim Self had a compact F cimbasso built in the shape of a euphonium, which has been named the "Jimbasso".[20] In 2004 Swiss brass instrument manufacturer Haag released a cimbasso in F built with five Hagmann valves and a 0.630-inch (16.0 mm) bore. Although discontinued, this instrument is used by several operas and orchestras, including Badische Staatskapelle, Hungarian State Opera, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and by Swedish jazz musician Mattis Cederberg.[21]

Repertoire and performance

Although the cimbasso in its modern form is most commonly used for performances of late Romantic Italian operas by Verdi and Puccini, since the mid 20th century it has found increased and more diverse use. In the late 1960s Mexican jazz musician Raul Batista Romero began featuring cimbasso in his albums.[22] Along with the contrabass trombone, it has increasingly been called for in film and video game soundtracks.[23] British composer Brian Ferneyhough calls for cimbasso in his large 2006 orchestral work Plötzlichkeit, and nu metal rock band Korn used two cimbassos in the live backing orchestra for their acoustic MTV Unplugged album.[24]

Historically informed performance of early cimbasso parts presents particular challenges. Unless proficient with period instruments such as serpent or ophicleide, it is difficult for orchestral low-brass players to perform on instruments that resemble the early cimbassi in form or timbre. It is also challenging for instrument builders to find good surviving examples to replicate or adapt.[25]

Although there is still a lack of consensus from conductors and orchestras, using a large-bore modern orchestral C tuba to play cimbasso parts is considered inappropriate by some writers and players. Meucci recommends using only a small, narrow-bore F tuba, or a bass trombone.[26] James Gourlay, conductor and former tubist with BBC Symphony Orchestra and Zürich Opera, recommends playing most cimbasso repertoire on the modern F cimbasso, as a compromise between the larger B♭ trombone contrabbasso Verdi instrument and the bass trombone. He also recommends using a euphonium in the absence of a period instrument for early cimbasso parts, which is closer to the sound of the serpent or ophicleide that would have been used before 1860.[27] Douglas Yeo, former bass trombonist with Boston Symphony Orchestra, even suggests that in a modern section of slide trombonists playing parts intended for valved instruments, it should not be unreasonable to perform the cimbasso part on a modern (slide) contrabass trombone.[28]

References

- ^ Meucci 1996, p. 155–6.

- ^ a b c

- Brass Instruments (PDF). Kraslice, Czech Republic: V.F. Červený & Synové. 2021. pp. 17–18. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- "Cimbasso" (in Italian). Milan: G&P Wind Instruments. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "Cimbasso". Weinfelden: Haag Brass. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "Cimbasso" (in German). Markneukirchen: Helmut Voigt. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "Contrabass Cimbasso". Markneukirchen: Jürgen Voigt. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "CB-900 Cimbasso in F". Bremen, Germany: Lätzsch Custom Brass. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- "Cimbasso". Melton Meinl Weston. Buffet Crampon. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "MJC Cimbassi". Mike Johnson Custom Instruments. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- "Cimbasso". Rudolf Meinl Metalblasinstrumente (in German). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "Cimbasso". Bremen: Thein Brass. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "Cimbassos". Wessex Tubas. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Meucci 1996, p. 144–5.

- ^ Meucci 1996, p. 157, note 69.

- ^ Bevan 2000, p. 81.

- ^ "Instruments: basson russe". Berlioz Historical Brass. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Myers 1986, pp. 134–136.

- ^ a b Meucci 1996, p. 158–9.

- ^ Bevan 2000, p. 406–13.

- ^ Bevan 2000, p. 414.

- ^ Yeo 2021, pp. 36–37, "contrabass trombone".

- ^ "Posaune; III. Sondermodelle". Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik (in German). Vol. 7 (2nd ed.). Kassel, New York: Bärenreiter. 1994. p. 877. ISBN 978-3-761-81139-9. LCCN 95116833. OCLC 882180506. Wikidata Q112109526. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Gourlay 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Meucci, Renato (2001). "Cimbasso". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.05789. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Yeo 2021, p. 152, "trombone basso Verdi".

- ^ Meucci 1996, p. 158, Fig. 13 (p. 179).

- ^ Rudolf Meinl Prospekt (PDF). Diespeck, Bavaria: Rudolf Meinl Musikinstrumenten-Herstellung. 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Brass Instruments (PDF). Kraslice, Czech Republic: V.F. Červený & Synové. 2021. pp. 17–18. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "MJC Cimbassi". Mike Johnson Custom Instruments. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Jim Self's Instruments". Basset Hound Music. 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Haag Cimbasso Trombone C45HV". Haag Trombones. Musik Haag AG. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 12 March 2013 suggested (help) - ^ "Raul Batista Romero". Jazz Musicians. All About Jazz. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Kifer 2020, p. 85–86.

- ^ Korn (2007). "MTV Unplugged". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Meucci 1996, p. 162.

- ^ Meucci 1996, p. 161–2.

- ^ Gourlay 2001, p. 8–9.

- ^ Yeo 2017, p. 246.

Bibliography

- Bevan, Clifford (2000). The Tuba Family (2nd ed.). Winchester: Piccolo Press. ISBN 1-872203-30-2. OCLC 993463927. OL 19533420M. Wikidata Q111040769.

- Gourlay, James (2001), The Cimbasso: Perspectives on Low Brass performance practise in Verdi's music (PDF), Wikidata Q118373994, archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2007

- Kifer, Shelby Alan (2020), The Contrabass Trombone: Into the Twenty-First Century, doi:10.17077/ETD.005304, Wikidata Q118378306

- Meucci, Renato (1996). "The Cimbasso and Related Instruments in 19th-Century Italy". The Galpin Society Journal. 49. Translated by William Waterhouse (published March 1996): 143–179. ISSN 0072-0127. JSTOR 842397. Wikidata Q111077162.

- Myers, Arnold (1986). "Fingering Charts for the Cimbasso and Other Instruments". The Galpin Society Journal. 39 (published September 1986): 134–136. doi:10.2307/842143. ISSN 0072-0127. JSTOR 842143. Wikidata Q118373974.

- Yeo, Douglas (2017). The One Hundred Essential Works for the Symphonic Bass Trombonist. Maple City: Encore Music Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5323-3145-9. OCLC 982957903. OL 47303018M. Wikidata Q111957781.

- Yeo, Douglas (2021). An Illustrated Dictionary for the Modern Trombone, Tuba, and Euphonium Player. Dictionaries for the Modern Musician. Illustrator: Lennie Peterson. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-538-15966-8. LCCN 2021020757. OCLC 1249799159. OL 34132790M. Wikidata Q111040546.

External links

Media related to Cimbasso at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cimbasso at Wikimedia Commons