Short SB.4 Sherpa: Difference between revisions

→Testing: Transonic normally only has one s, fixed. |

m Copy edit |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

|} |

|} |

||

The '''Short SB.4 Sherpa''' was an experimental aircraft designed and produced by the [[United Kingdom|British]] aircraft manufacturer [[Short Brothers]]. Only a single example was ever produced. |

The '''Short SB.4 Sherpa''' was an experimental aircraft designed and produced by the [[United Kingdom|British]] aircraft manufacturer [[Short Brothers]]. Only a single example was ever produced. |

||

| Line 44: | Line 45: | ||

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was an experimental aircraft, featuring an unusual [[aero-isoclinic wing]].<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4423."/> This radical wing configuration was designed to maintain a constant [[angle of incidence (aerodynamics)|angle of incidence]] regardless of flexing, by placing the [[Torsion (mechanics)|torsion]] box well back in the wing so that the air loads, acting in the region of the quarter-[[Chord (aircraft)|chord]] line, have a considerable [[Moment (physics)|moment arm]] about it. The torsional instability and tip stalling characteristics of conventional [[swept wing]]s were recognised at the time, together with their tendency to [[Control reversal|aileron-reversal]] and [[Aeroelasticity#Flutter|flutter]] at high speed; the aero-isoclinic wing was designed to specifically prevent these undesirable effects.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4413.">Barnes 1967, pp. 441-443.</ref> |

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was an experimental aircraft, featuring an unusual [[aero-isoclinic wing]].<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4423."/> This radical wing configuration was designed to maintain a constant [[angle of incidence (aerodynamics)|angle of incidence]] regardless of flexing, by placing the [[Torsion (mechanics)|torsion]] box well back in the wing so that the air loads, acting in the region of the quarter-[[Chord (aircraft)|chord]] line, have a considerable [[Moment (physics)|moment arm]] about it. The torsional instability and tip stalling characteristics of conventional [[swept wing]]s were recognised at the time, together with their tendency to [[Control reversal|aileron-reversal]] and [[Aeroelasticity#Flutter|flutter]] at high speed; the aero-isoclinic wing was designed to specifically prevent these undesirable effects.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4413.">Barnes 1967, pp. 441-443.</ref> |

||

In the Sherpa, the wing, which was used without a [[tailplane]], was fitted with [[Aileron#Wingtip ailerons|rotating tips]] comprising approximately one-fifth of the total wing area. Unlike pure wingtip ailerons, these surfaces were a bit more like "wingtip [[elevon]]s", as they were rotated together (to act as [[Elevator (aircraft)|elevator]]s) or in opposition (when they acted as [[aileron]]s). They were hinged at about 30% chord and each carried, on the trailing edge, a small anti-balance tab, the fulcrum of which could be moved by means of an electric actuator. It was expected that the rotary wing tip controls would prove greatly superior to the flap type at [[transonic]] speeds and provide greater |

In the Sherpa, the wing, which was used without a [[tailplane]], was fitted with [[Aileron#Wingtip ailerons|rotating tips]] comprising approximately one-fifth of the total wing area. Unlike pure wingtip ailerons, these surfaces were a bit more like "wingtip [[elevon]]s", as they were rotated together (to act as [[Elevator (aircraft)|elevator]]s) or in opposition (when they acted as [[aileron]]s). They were hinged at about 30% chord and each carried, on the trailing edge, a small anti-balance tab, the fulcrum of which could be moved by means of an electric actuator. It was expected that the rotary wing tip controls would prove greatly superior to the flap type at [[transonic]] speeds and provide greater manoeuvrability at high altitudes.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4434.">Barnes 1967, pp. 443-444.</ref> |

||

In terms of its construction, the Sherpa was primarily composed of light [[alloy]]s and featured a [[monocoque]] arrangement.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4434."/> Wing sweep-back on the leading edge was just over 42° to facilitate low-speed research. The Sherpa was provisioned with a conventional [[tricycle landing gear|tricycle undercarriage]].<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4434."/> Two diminutive engines ([[Turbomeca Palas]]) were buried in the upper fuselage with a [[NACA duct|NACA flush inlet]] on the top of the fuselage and toed-out exhausts located at the wing roots. Fuel was housed within the fuselage in two 250 gallon tanks, which were balanced around the aircraft's |

In terms of its construction, the Sherpa was primarily composed of light [[alloy]]s and featured a [[monocoque]] arrangement.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4434."/> Wing sweep-back on the leading edge was just over 42° to facilitate low-speed research. The Sherpa was provisioned with a conventional [[tricycle landing gear|tricycle undercarriage]].<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4434."/> Two diminutive engines ([[Turbomeca Palas]]) were buried in the upper fuselage with a [[NACA duct|NACA flush inlet]] on the top of the fuselage and toed-out exhausts located at the wing roots. Fuel was housed within the fuselage in two 250 gallon tanks, which were balanced around the aircraft's centre of gravity; electrical power was supplied by a [[ram air turbine]] by the engines.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 444.">Barnes 1967, p. 444.</ref> [[Blackburn Aircraft|Blackburn]], who produced the Palas under licence, hoping to market these engines as a new product line, supplied the powerplants for the Sherpa programme.<ref>Gunston 1977, p. 512.</ref> |

||

==Testing== |

==Testing== |

||

| Line 55: | Line 56: | ||

During the initial series of flying trials of the Sherpa, performed largely by Brooke-Smith, the aircraft had reportedly proved to be quite satisfactory; its docile handling characteristics led to be being described as being 'one of the most graceful aircraft now flying'.<ref>Shorts Quarterly Review, Autumn 1953.</ref><ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 444."/> The aircraft was typically flown within a restricted flight envelope, during which it reportedly achieved a "flat-out" speed of {{convert|170|mi/h|km/h|-1|abbr=on}} at {{convert|5000|ft|m|-2|abbr=on}},<ref name="Barnes and James 1989, p. 444.">Barnes and James 1989, p. 444.</ref> which made it amongst the slowest jet-powered aircraft to have ever flown.<ref name="Barnes and James 1989, p. 444."/><ref name="Gunston 1977, p. 513.">Gunston 1977, p. 513.</ref> |

During the initial series of flying trials of the Sherpa, performed largely by Brooke-Smith, the aircraft had reportedly proved to be quite satisfactory; its docile handling characteristics led to be being described as being 'one of the most graceful aircraft now flying'.<ref>Shorts Quarterly Review, Autumn 1953.</ref><ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 444."/> The aircraft was typically flown within a restricted flight envelope, during which it reportedly achieved a "flat-out" speed of {{convert|170|mi/h|km/h|-1|abbr=on}} at {{convert|5000|ft|m|-2|abbr=on}},<ref name="Barnes and James 1989, p. 444.">Barnes and James 1989, p. 444.</ref> which made it amongst the slowest jet-powered aircraft to have ever flown.<ref name="Barnes and James 1989, p. 444."/><ref name="Gunston 1977, p. 513.">Gunston 1977, p. 513.</ref> |

||

Data from these flights was typically captured by an onboard [[flight data recorder]] and analysed post-flight to build up a model of how a similar full-sized wing would behave under various conditions, including various altitudes and speeds.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 444."/> Keith-Lucas had aimed to validated the wing as a low weight solution that behaved well across various speeds, including the [[ |

Data from these flights was typically captured by an onboard [[flight data recorder]] and analysed post-flight to build up a model of how a similar full-sized wing would behave under various conditions, including various altitudes and speeds.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 444."/> Keith-Lucas had aimed to validated the wing as a low weight solution that behaved well across various speeds, including the [[transonic]] range, but the attained test results did not fully validate his hopes.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4445.">Barnes 1967, pp. 444-445.</ref> Aviation author Bill Gunston notes that, despite the Sherpa having attaining its design goals, the concept was considered to be "not fully realised in practice" and the project was eventually wound up without a direct continuation.<ref name="Gunston 1977, p. 513."/> Shorts did prepare multiple proposals, such as the retrofitting of the [[Supermarine Swift]] fighter with the aero-isoclinic wing, but these were not pursued.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 445.">Barnes 1967, p. 445.</ref> |

||

The Sherpa itself was subsequently donated to the [[Cranfield University|College of Aeronautics]] at [[Cranfield]], where it continued to fly up until 1958. At this point, engine issues forced the aircraft to be grounded until replacement powerplants could be organised.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 445."/> During 1960, further engines were made available, thus flying of the Sherpa resumed until 1964, when, with its engine life expired, the Sherpa was finally grounded. Following this, it was transported to the Bristol College of Advanced Technology, where the airframe was used as a "laboratory specimen".<ref name="Gunston 1977, p. 513."/><ref>Barnes and James 1989, p. 445.</ref> Its fuselage was on display at the [[Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum]], near [[Bungay, Suffolk|Bungay]], [[Suffolk]],<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4456.">Barnes 1967, pp. 445-446.</ref> until 17 July 2008, after which it was moved to the Lisburn site of the [[Ulster Aviation Society]].<ref>[http://www.ulsteraviationsociety.org/#/short-sb4-sherpa/4537302722 Ulster Aviation Society SB4 page]</ref> |

The Sherpa itself was subsequently donated to the [[Cranfield University|College of Aeronautics]] at [[Cranfield]], where it continued to fly up until 1958. At this point, engine issues forced the aircraft to be grounded until replacement powerplants could be organised.<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 445."/> During 1960, further engines were made available, thus flying of the Sherpa resumed until 1964, when, with its engine life expired, the Sherpa was finally grounded. Following this, it was transported to the Bristol College of Advanced Technology, where the airframe was used as a "laboratory specimen".<ref name="Gunston 1977, p. 513."/><ref>Barnes and James 1989, p. 445.</ref> Its fuselage was on display at the [[Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum]], near [[Bungay, Suffolk|Bungay]], [[Suffolk]],<ref name="Barnes 1967, p. 4456.">Barnes 1967, pp. 445-446.</ref> until 17 July 2008, after which it was moved to the Lisburn site of the [[Ulster Aviation Society]].<ref>[http://www.ulsteraviationsociety.org/#/short-sb4-sherpa/4537302722 Ulster Aviation Society SB4 page]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:04, 15 May 2023

| SB.4 Sherpa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Short Sherpa demonstrating at the Farnborough SBAC Show in September 1954 | |

| Role | Experimental aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Short Brothers |

| Designer | David Keith-Lucas |

| First flight | 4 October 1953 |

| Primary users | Short Brothers company experimental project College of Aeronautics (Cranfield) |

| Number built | 1 |

| Developed from | Short SB.1 |

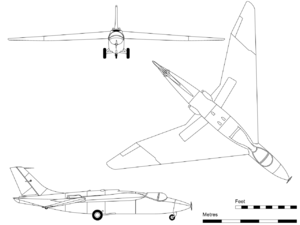

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was an experimental aircraft designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Short Brothers. Only a single example was ever produced.

The Sherpa was developed during the 1950s for the purpose of testing a novel wing design, referred to as an aero-isoclinic wing. It was believed that this wing design could possess favourable qualities for producing tailless aircraft, and that the Sherpa would validate the characteristics of the wing for such aircraft to be produced in the future. While such a wing had been flown on the earlier Short SB.1, an unpowered glider, it was deemed valuable to use a powered aircraft instead. The design of the Sherpa is largely based upon that of the SB.1, to the extent that it incorporated numerous elements of this aircraft.

The Sherpa performed its maiden flight on 4 October 1953, after which it spent several years performing experimental flights and the occasional aerial display. After gathering sufficient data for Shorts' purposes, the company decided that it did not show sufficient potential as to continue its research into the aero-isoclinic wing. The sole Sherpa was donated to the College of Aeronautics at Cranfield during the late 1950s and flown for numerous years. It was eventually grounded and used as a static laboratory specimen at the Bristol College of Advanced Technology, before being preserved and put on display at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum.

Development

The origins of the Short SB.4 Sherpa can be traced back to the 1920s and the activities of Professor Geoffrey T.R. Hill, who was pivotal in the design of the Westland-Hill Pterodactyl, a pioneering tailless experimental aircraft.[1] Even prior to the First World War, Shorts had been involved in tailless aircraft research, but interest in the field reached new heights in the years immediately following the Second World War. During the late 1940s, the company worked on multiple proposals for tailless aircraft in response to specifications issued by the Air Ministry, including Specification X.30/46 and Specification B.35/46, which sought a military assault glider and strategic bomber respectively.[2]

In particular, one of the company's aeronautical engineers, David Keith-Lucas, was keen to eliminate the parasitic drag normally incurred by the presence of a conventional tail and fuselage, and thus was a keen proponent of the tailless approach.[3] He also observed that directional stability was a critical issue without the application of traditional fins and rudders; it was identified that the outermost parts of the wing could be rotated and repositioned to function as elevons for stability and control purposes. New wing designs that presented a low aspect ratio, such as the delta wing, had been observed to reduce the onset of these issues; Keith-Lucas and Hill, jointly developed what became known as the aero-isoclinic wing.[4]

Having become sufficiently confident in the merits of the aero-isoclinic wing , Shorts opted to produce a new experimental aircraft to incorporate the latest advances and explore its behaviour, thus it constructed the Short SB.1 glider.[4] This aircraft was designed to be as inexpensive as possible and thus featured extensive wooden construction alongside its innovative wing.[5] After only a few months of flight, the SB.1 suffered damage in a heavy landing at RAF Aldergrove on 17 October 1951. Shorts' chief test pilot, Tom Brooke Smith, objected to further flights of the unpowered glider. Accordingly, it was decided that the fuselage, which had been heavily damaged, would be replaced by a modified design that incorporated a pair of Turbomeca Palas turbojet engines.[6]

Design

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was an experimental aircraft, featuring an unusual aero-isoclinic wing.[6] This radical wing configuration was designed to maintain a constant angle of incidence regardless of flexing, by placing the torsion box well back in the wing so that the air loads, acting in the region of the quarter-chord line, have a considerable moment arm about it. The torsional instability and tip stalling characteristics of conventional swept wings were recognised at the time, together with their tendency to aileron-reversal and flutter at high speed; the aero-isoclinic wing was designed to specifically prevent these undesirable effects.[7]

In the Sherpa, the wing, which was used without a tailplane, was fitted with rotating tips comprising approximately one-fifth of the total wing area. Unlike pure wingtip ailerons, these surfaces were a bit more like "wingtip elevons", as they were rotated together (to act as elevators) or in opposition (when they acted as ailerons). They were hinged at about 30% chord and each carried, on the trailing edge, a small anti-balance tab, the fulcrum of which could be moved by means of an electric actuator. It was expected that the rotary wing tip controls would prove greatly superior to the flap type at transonic speeds and provide greater manoeuvrability at high altitudes.[8]

In terms of its construction, the Sherpa was primarily composed of light alloys and featured a monocoque arrangement.[8] Wing sweep-back on the leading edge was just over 42° to facilitate low-speed research. The Sherpa was provisioned with a conventional tricycle undercarriage.[8] Two diminutive engines (Turbomeca Palas) were buried in the upper fuselage with a NACA flush inlet on the top of the fuselage and toed-out exhausts located at the wing roots. Fuel was housed within the fuselage in two 250 gallon tanks, which were balanced around the aircraft's centre of gravity; electrical power was supplied by a ram air turbine by the engines.[9] Blackburn, who produced the Palas under licence, hoping to market these engines as a new product line, supplied the powerplants for the Sherpa programme.[10]

Testing

On 4 October 1953, the Sherpa performed its maiden flight, piloted by Shorts' Chief Test Pilot, Tom Brooke-Smith.[9] Brooke-Smith had also piloted the earlier experimental glider aircraft, the Short SB.1, upon which the Sherpa was based. Although he sustained injuries in the crash landing of the SB.1, Brooke-Smith had quickly recovered and was able to undertake the test programme of the redesignated SB.4 (registered as G-14-1) throughout 1953–1954. (Incidentally, the Sherpa was named following the conquest of Mount Everest but derived its name specifically from its company designation "Short & Harland Experimental Research Prototype Aircraft.[9])

During the initial series of flying trials of the Sherpa, performed largely by Brooke-Smith, the aircraft had reportedly proved to be quite satisfactory; its docile handling characteristics led to be being described as being 'one of the most graceful aircraft now flying'.[11][9] The aircraft was typically flown within a restricted flight envelope, during which it reportedly achieved a "flat-out" speed of 170 mph (270 km/h) at 5,000 ft (1,500 m),[12] which made it amongst the slowest jet-powered aircraft to have ever flown.[12][13]

Data from these flights was typically captured by an onboard flight data recorder and analysed post-flight to build up a model of how a similar full-sized wing would behave under various conditions, including various altitudes and speeds.[9] Keith-Lucas had aimed to validated the wing as a low weight solution that behaved well across various speeds, including the transonic range, but the attained test results did not fully validate his hopes.[14] Aviation author Bill Gunston notes that, despite the Sherpa having attaining its design goals, the concept was considered to be "not fully realised in practice" and the project was eventually wound up without a direct continuation.[13] Shorts did prepare multiple proposals, such as the retrofitting of the Supermarine Swift fighter with the aero-isoclinic wing, but these were not pursued.[15]

The Sherpa itself was subsequently donated to the College of Aeronautics at Cranfield, where it continued to fly up until 1958. At this point, engine issues forced the aircraft to be grounded until replacement powerplants could be organised.[15] During 1960, further engines were made available, thus flying of the Sherpa resumed until 1964, when, with its engine life expired, the Sherpa was finally grounded. Following this, it was transported to the Bristol College of Advanced Technology, where the airframe was used as a "laboratory specimen".[13][16] Its fuselage was on display at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum, near Bungay, Suffolk,[17] until 17 July 2008, after which it was moved to the Lisburn site of the Ulster Aviation Society.[18]

Aircraft on display

The sole SB.4 is on display at the Ulster Aviation Collection, Long Kesh Airfield, near Belfast[19]

Specifications

Data from Shorts Aircraft since 1900.[20]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 31 ft 10 in (9.7 m)

- Wingspan: 38 ft 0 in (11.58 m) sweepback 42 degrees

- Height: 9 ft 1.12 in (2.77 m)

- Wing area: 230 sq ft (21.4 m2)

- Empty weight: 3,000 lb (1,400 kg)

- Gross weight: 3,268 lb (1,482 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Blackburn Turbomeca Palas turbojet, 350 lbf (1.6 kN) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 170 mph (275 km/h, 150 kn)

- Cruise speed: 117 mph (188 km/h, 102 kn)

- Endurance: 45-50 min

- Service ceiling: 5,000 ft (1,500 m)

See also

Related development

References

Citations

- ^ Barnes 1967, pp. 439-440.

- ^ Barnes 1967, pp. 439-441.

- ^ Barnes 1967, p. 441.

- ^ a b Barnes 1967, pp. 441-442.

- ^ Barnes 1967, p. 442.

- ^ a b Barnes 1967, pp. 442-443.

- ^ Barnes 1967, pp. 441-443.

- ^ a b c Barnes 1967, pp. 443-444.

- ^ a b c d e Barnes 1967, p. 444.

- ^ Gunston 1977, p. 512.

- ^ Shorts Quarterly Review, Autumn 1953.

- ^ a b Barnes and James 1989, p. 444.

- ^ a b c Gunston 1977, p. 513.

- ^ Barnes 1967, pp. 444-445.

- ^ a b Barnes 1967, p. 445.

- ^ Barnes and James 1989, p. 445.

- ^ Barnes 1967, pp. 445-446.

- ^ Ulster Aviation Society SB4 page

- ^ Ulster Aviation Society website

- ^ Barnes and James 1989, p. 446.

Bibliography

- Barnes, C.H. Shorts Aircraft since 1900. London: Putnam, 1967.

- Barnes, C.H. with revisions by Derek N. James. Shorts Aircraft since 1900. London: Putnam, 1989 (revised). ISBN 0-85177-819-4.

- Buttler, Tony (May–June 1999). "Control at the Tips: Aero-isoclinics and Their Influence on Design". Air Enthusiast (81): 50–55. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Buttler, Tony and Jean-Louis Delezenne. X-Planes of Europe: Secret Research Aircraft from the Golden Age 1946-1974. Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications, 2012. ISBN 978-1-902-10921-3

- Gunston, Bill. "Short's Experimental Sherpa." Aeroplane Monthly, Vol. 5, no. 10. October 1977, pp. 508–515.

- "Sherpa - Fore-runner of High Speed, High Altitude Aircraft." Shorts Quarterly Review, Vol. 2, No. 3, Autumn 1953.

- Warner, Guy (July–August 2002). "From Bombay to Bombardier: Aircraft Production at Sydenham, Part One". Air Enthusiast. No. 100. pp. 13–24. ISSN 0143-5450.