Ğabdulla Tuqay: Difference between revisions

m Correct spelling |

+cap |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| image = Tuqay portrait.jpg |

| image = Tuqay portrait.jpg |

||

| imagesize = 200px |

| imagesize = 200px |

||

| caption = |

| caption = Portrait, {{circa|1910|1913}} |

||

| pseudonym = [[Şüräle]] |

| pseudonym = [[Şüräle]] |

||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1886|4|26|df=y}} |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1886|4|26|df=y}} |

||

Revision as of 22:46, 21 May 2023

Ğabdulla Tuqay Габдулла Тукай | |

|---|---|

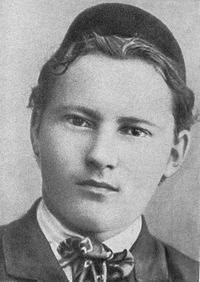

Portrait, c. 1910 – c. 1913 | |

| Born | Ğabdulla Möxämmätğärif uğlı Tuqayev 26 April 1886 Quşlawıç, Kazan Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 15 April 1913 (aged 26) Kazan, Russian Empire |

| Pen name | Şüräle |

| Occupation | poet, publicist |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Genre | romanticism, realism |

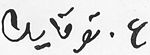

| Signature | |

| |

Ğabdulla Tuqay[1] (Tatar: عبد الله توقای April 26 [O.S. April 14] 1886 – April 15 [O.S. April 2] 1913) was a Volga Tatar poet, critic, publisher, and towering figure of Tatar literature. Tuqay is often referred to as the founder of the modern Tatar literature and the modern Tatar literary language, which replaced Old Tatar language in literature.[2]

Early life

Ğabdulla Tuqay was born in the family of the hereditary village mullah of Quşlawıç, Kazan Governorate, Russian Empire (current Tatarstan, Russia) near the modern town of Arsk. His father, Möxämmätğärif Möxämmätğälim ulı Tuqayıv, had been a village mandative mullah since 1864. In 1885 his wife died, leaving him a son and a daughter, and Möxämmätğärif married second wife, Mämdüdä, daughter of Öçile village mullah Zinnätulla Zäynepbäşir ulı. On 29 August O.S. Möxämmätğärif died when Ğabdulla was five months old. Soon Ğabdulla's grandfather also died and Mämdüdä was forced to return to her father and then to marry the mullah of the village of Sasna. Little Ğabdulla lived for some time with an old woman in his native village, before his new stepfather agreed to take Tuqay into his family. Tuqay's relatively happy childhood did not last long: on O.S. 18 January 1890 Ğabdulla's mother Mämdüdä also died, and Tuqay was removed to his poor grandfather Zinnätulla. Lacking enough food even for his own children, his grandfather sent Ğabdulla to Kazan with a coachman. There the coachman took Tuqay to a market-place, Peçän Bazaar, hoping to find someone willing to adopt the child. A tanner named Möxämmätwäli and his wife Ğäzizä from the Yaña-Bistä area of Kazan decided to take care of him. While living in Kazan, Tuqay was taken ill with walleye. In 1892, when both of Ğabdulla's adoptive parents became sick they had to send him back to his grandfather. This time, Ğabdulla's grandfather sent the child for further adoption to the village of Qırlay, where Ğabdulla stayed with the family of a peasant Säğdi. During his stay with this family, Ğabdulla was sent to the local madrassah (religious school), for the first time in his life, where, in his own words, his enlightenment began.

In the fall of 1895, the Ğosmanovs, Tatar merchants living in Uralsk, decided to adopt their distant relatives, because their own children had died. Ğäliäsğar Ğosmanov and his wife Ğäzizä, Ğabdulla's aunt, asked a peasant from Quşlawıç to bring them Ğabdulla. The peasant took ten-year-old Tuqay away from Säğdi, threatening him with Russian papers and the village constable. Living in Uralsk, Ğabdulla attended to Motíğía madrassah. Simultaneously, in 1896, he started to attend a Russian school. There, for the first time in his life, he became acquainted with the world of Russian literature and started to write poetry. In 1899 the anniversary of Alexander Pushkin was widely celebrated in Uralsk, an event which inspired Tuqay's interest in Russian poetry, especially works by Pushkin.

Ğosmanov tried to interest Ğabdulla in his work, but Tuqay stayed indifferent to the merchant's lot, preferring to develop his education. On 30 July 1900 Ğäliäsğar Ğosmanov died of "stomach diseases", so Tuqay moved into the madrassah itself, living first in common room, and two years later in a khujra, an individual cell. In the madrassah Tuqay proved himself a diligent student, completing in ten years a program intended for fifteen. However, he continued to live in poverty.

By 1902, Ğabdulla, age 16, had changed his nature. He lost interest in studying the Qur'an, and showed criticism to all that was taught in madrassah. He didn't shave his hair, he drank beer and even smoked. At the same time, he became more interested in poetry.[3]

Literary life

Uralsk period

Beginning in his madrassah years, Tuqay was interested in folklore and popular poetry, and he asked shakirds, coming for different jobs all over Idel-Ural during summer vacations, to collect local songs, examples of bäyet, i.e. epic poem and fairy-tales. In the madrassah itself he became familiar with Arabic, Persian and Turkish poetry, as well as poetry in the Old Tatar language of the earlier centuries. In 1900 Motíğía graduate, a Tatar poet Mirxäydär Çulpaní visited the madrassah. Ğabdulla met him and Çulpaní became the first living poet to impress Tuqay. Çulpaní wrote in "elevated style", using aruz, an Oriental poetic system, and mostly in Old Tatar language, full of Arab, Persian and Turkish words, and rather distant from the Tatar language itself. In 1902-1903 he met a Turkish poet Abdülveli, concealed himself there from Abdul Hamid II pursuits. Thus, Tuqay adopted Oriental poetic tradition.

Young teacher, the son of headmaster, Kamil "Motíğí" Töxfätullin, organized wallpaper Mäğärif (The Education) and hand-written journals. The first odes of Tuqay were published there, and he was referred as "the first poet of the madrassah".

In 1904 Motíğí founded his own publishing company, and Tuqay became clerk there. He combined this job with teaching younger shakirds in the madrassah. He introduced new methods, typical for the Russian school.

After the October Manifesto of 1905 it became possible to publish newspapers in the Tatar language, which was strictly forbidden earlier. However, Motíğí wasn't enough solvent to open his own newspaper, so he bought the Russian language newspaper Uralets with typography, to print also a Tatar newspaper there. Tuqay became a typesetter. The newspaper was named Fiker (The Thought). Then Motíğí started to issue Älğasrälcadid (The New Century) magazine. Tuqay sent his first verses there to be published. At the same time he started writing for a newspaper and began participating in the publishing of several Tatar magazines. At day Tuqay worked in typography (he was already a proofreader), but by nights he wrote verses, so every issue of Fiker, Nur and Älğasrälcadid contains his writing. More over, he wrote articles, novels and feuilletons for those periodicals, he translated Krylov fables for the magazine. It is also known that Tuqay spread social-democratic leaflets and translated social-democratic brochure to the Tatar language.

Despite social-democrats' negative attitude towards the Manifesto, in his verses Tuqay admired with Manifesto, believing in the progressive changes of the Tatar lifestyle. During that period he shared his views with liberals, as the long-standing tradition of the Tatar enlightenment didn't distinguish national-liberation movement from the class struggle and negated the class struggle within Tatar nation. The most prominent writings of that period are Millätä (To the Nation) poem and Bezneñ millät, ülgänme, ällä yoqlağan ğınamı? (Has our nation dead, or just sleeps?) article. Since the satirical magazine Uqlar (The Arrows) appeared in Uralsk, Tuqay renowned himself as satirist. The main target of his jeers was Muslim clergy, who stayed opposed to progress and Europeanization. As for the language of the most of his verses, it still stayed the Old Tatar language and continued the Oriental traditions, such as in Puşkinä (To Pushkin). However, in some of them, directed to the Tatar peasantry a pure Tatar was used, what was newly for the Tatar poetry.

In January 1906 police conducted a search of the typography, as rebellious articles were published in the newspaper. The First State Duma was dismissed, the revolution came to naught. The ultra-right Russian nationalists from the Black Hundred proposed that Tatars emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. That period his most prominent verses devoted to the social themes and patriotism were composed: Gosudarstvennaya Dumağa (To the State Duma), Sorıqortlarğa (To the Parasites) and Kitmibez! (We don't leave!). Tuqay was disappointed in liberalism and sympathized with socialists, especially Esers. In Kitmibez! he answered to the Black Hundred that the Tatars are a brother people of the Russians and immigration to Turkey is impossible.

On 6 January 1907 Tuqay left madrassah, as his fee permitted him to live independently, and settled in a hotel room. He became an actual editor of Uqlar, being the lead poet and publicist of all Motíğí's periodicals. That time liberal Fiker and Tuqay himself was in confrontation with Qadimist, i.e. ultraconservative Bayan al-Xaq, which even called for pogrom of liberal press activists. However, that year he was surprisingly discharged, as the result of the conflict with Kamil Motíğí and instigation of the typography workers for a strike to raise a salary. On 22 February 1907 Motíğí was deprived of publishing rights and his publishers was sold to merchant, who attracted Tuqay to the work again, but sonly dismissed the periodicals.

That time Tuqay departed from the social-democrats and politics generally, preferring to devote himself to poetry. Since mid-1906 to autumn 1907 more than 50 verses were written, as well as 40 articles and feuilletons. That time he turned to a pure Tatar, using a spoken language. Impressed by Pushkin's fairy-tale poem Ruslan and Lyudmila, Tuqay wrote his first poem, Şüräle.

It is known, that Motíğí tried to establish another newspaper, Yaña Tormış (The New Life) in Uralsk, with Tuqay as one of constitutors, but that time Ğabdulla was already so popular in the Tatar society, that chief editors from Kazan, the Tatar cultural capital, offered him job. Moreover, Tuqay should be examined by a draft board in his native uyezd, and he left Uralsk anyway. The admiration with the future trends of his life in Kazan is expressed in Par at (The Pair of Horses), which consequently became the most associated with Kazan Tatar verse.[3]

Kazan period

Just after the arrival to Kazan, Tuqay stayed at Bolğar hotel and met Tatar literature intelligentsia, such as playwright and Yoldız newspaper secretary Ğäliäsğar Kamal and prominent Tatar poet and Tañ yoldızı newspaper chief editor Säğit Rämiev. Several days after he left Kazan to be examined by a draft board, assembly point being in Ätnä village. There he was discarded due his poor health and walleye and freed up of serving in the Russian Imperial Army. He returned to Kazan and renowned his literature and publishing activity.

He was adopted to the editorial staff of democratically oriented Äl-İslax gazette, led by Fatix Ämirxan and Wafa Bäxtiärev. However, the newspaper had a little budget. Tuqay had got fixed up as a forwarding agent in Kitap publishers, to provide guaranteed wage. Moreover, he refused offer from Äxbar, an organ of Ittifaq al-Muslimin, a political party, close to Kadets, as well as other offers from rich, but right-wing newspapers. He also continued self-education: read Russian classics, critiques, and studied German language. He was interested in studying the life of common people by visiting bazaars and pubs.

Tuqay's room in Bolğar hotel was frequently visited by admirers from "gilded youth". As he wrote, their boozing-up impeded him and his creation. Nevertheless, in the end of 1907-1908 he wrote nearby sixty verses and twenty articles in Äl-İslax and satirical journal Yäşen (The Illumination), and also published two books of verses. The most prominent satire of that period was Peçän Bazarı yaxud Yaña Kisekbaş (The Hay Bazaar or New Kişekbaş), deriding problems of the Tatar society of the period, clergy and merchant class.

As for Tuqay's personal life, there is known little about it. As usual he avoided women in his circle. It is known that he was enamored of Zäytünä Mäwlüdova, his 15-year-old admirer. Several verses were devoted to Zäytünä and their feelings, such as A Strange Love. However, later Tuqay did not develop their relations, and the possible reason was inferiority complex, attributed to his health and financial position.

In May 1908 an article, comparing Tuqay's, Rämiev's and Majit Ghafuri's poetries was published in Russian-language Volzhsko-Kamsky Vestnik. In August 1908 Kamal founded satirical journal Yäşen under Tuqay's pressure. The most of published works were written by Tuqay, of course. In August 1908 Kamal and Tuqay visit the Makaryev Fair, placed in Nizhny Novgorod. There Tuqay temporarily joined the first Tatar theatre troupe, Säyyar, singing national songs and declaiming his verses from scene. On 14 October Ğabdulla Tuqay presented his new satirical poem The Hay Bazaar or New Kisekbaş, based on classical Old Tatar poem Kisekbaş. In own poem he derided nationalism among Tatars, as well as Wäisi sect's fanatics, associating sect's leader, Ğaynan Wäisev with Diü, an evil spirit from Kisekbaş.[3]

1909–1910 crisis

In 1909–1910 all freedoms, gained by 1905 revolution came to naught under Stolypin's policy. As a result, leftist sympathized Ğabdulla Tuqay was nearly disappointed in his activity and was in depression. Another reason was in his friends, moved to rightist newspapers, like Kamal and Rämiev. The most of his verses were depressive, however, Tuqay stayed productive, he published nearby hundred verses, two fairy tale poems, autobiography, and an article about Tatar folklore (Xalıq ädäbiäte, i.e. Folk Literature), wrote thirty feuilletons and printed twenty books, not only with own poems, but also compiled of folk songs.

In those years Tuqay became staunch leftist, despite of his staying with one bourgeois family for some time: Äl-İslax became a leftist political newspaper only, Tuqay criticized all his former friends, turned to the right or liberal newspapers: Zarif Bäşiri from Oremburgean Çükeç and Säğit Rämiev from Bäyänelxaq. He called them bourgeoisie's stooges, in response their stigmatized Tuqay Russophile. The same time Okhrana reported his poems as Russophobic. Also Tuqay became closer to the first Tatar Marxist, Xösäyen Yamaşev.

In June 1909 Yäşen, was closed due to financial problems as well as censorship requirement, as well as Äl-İslax. Being at the top of his crisis, he thinks about suicide, but since March 1910 a new satirical magazine, Yal-Yolt (The Lightning) was published in Kazan under Äxmät Urmançiev.

Being interested in Leo Tolstoy ideas and legacy, Tuqay felt keenly the death of the Russian genius. Pointing out a high role of children's education, he prepared two books for children, and two schoolbooks of Tatar literature. In total, he composed more than fifty verses and seven poems for children.[3]

Ufa — Saint-Petersburg — Troitsk

In 1911 Qadimist forces allied with Okhrana fulminated İj-Bubí, the most progressive Tatar madrassah. This fact filled with indignation all Tatar intelligentsia. But it was only a beginning of campaign drive against Tatar democracy, which became Tuqay's tragedy again. However, as it known from Tuqay's letters to his friend Säğit Sönçäläy, he decided to write the Tatar Eugene Onegin, but he had to recover his health. He planned a trip to the southern regions to receive kumiss therapy there.

In April he left Kazan and had a voyage by the Volga to Astrakhan. There he met Rämiev and became reconciled with him. Three weeks later he moved to Kalmyk Bazary village and stayed with schoolteacher Şahit Ğäyfi there. As Ğäyfi was interested in photography, they shot a series of cards, devoted to Tuqay's poems and the Tatar theatre. Returning to Kazan, he published, Miäwbikä (Pussycat), his prominent poem for children. There he applied new poetic methods, and was criticized therefore. He also was interested to publish his prohibited verses in the newspaper of the Russian Muslims, published in Paris, but later he refused of this idea, as the newspaper propagated pan-Islamist ideas.

In autumn 1911 a famine stroke Idel-Ural. The Autumn Wind was devoted to the famine and hard lot of peasantry. Tuqay felt ill with malaria and unfortunately moved to cold hotel number. So, he abandoned all and moved to Öçile, to his relatives. There he passed winter, writing o recomposing his verses, sometimes sending new feuilletons to the editors. Possible, another reason of his departure was a trial of his book, published as early as in 1907. He returned in February 1912. In March 1912 his friend, Yamaşev dead of infarction and Tuqay devoted a feeling poem (Xörmätle Xösäyen yädkâre, i.e. Of Blessed Memory of Xösäyen) to the first Tatar Marxist.

In April Ğabdulla Tuqay went on a tour again. First he arrived to Ufa, where he met Majit Ghafuri. Then he left Ufa and moved to Saint-Petersburg. He stayed with Musa Bigiev. In Saint Petersburg he met with local Tatar diaspora's youth, many of whom were students and leftist activists. The impression of them is expressed in The Tatar Youth (Tatar yäşläre) verse, full of optimism. However, he didn't know that he has the last stage of tuberculosis: a doctor, examined him in Saint Petersburg, preferred to keep diagnosis back. He was advised to take a course in Switzerland, but he refused and after farewell party moved to Ufa again, and then to Troitsk. There he lived till July 1912 among the Kazakh nomads in the steppe, receiving kumiss therapy.[3]

Death

His last year he began full of optimism: the revolutionary tendencies rose, and social theme appeared in his poetry again. In Añ (The Consciousness) and Dahigä (To the Genius) he wrote that his struggle, as well as the 1905 revolution, was not vain. Many verses were devoted to the peasantry's problems, resembling Nekrasov's poetry. More and more verses were banned; some of them were only published after the October Revolution. However, Tuqay was criticized by Ğälimcan İbrahimov, that now his poetry worsened.

In summer 1912 he published his last book, The Mental Food, a collection of 43 verses and one poem. But then his health deteriorated. In spite of this, he found energy to write for the new literature magazine Añ and the democratic newspaper Qoyaş (The Sun), edited by Fatix Ämirxan. As Ämirxan was paralyzed, they stayed in neighboring rooms of the Amur Hotel, where the editorial board was situated. In the first days of 1913 he wrote The Frost, a witty poem depicting how Kazaners of different social classes behave during frost. The next notable poem was devoted to the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty. The poem was rather panegyrical, as was the vulgar-sociological critique of the early 1920s, based on this poem, proclaimed Tuqay to be a pan-Islamist and Tsarist. However, the end of the verse is written not about Tsar's dynasty, but about internationalism within Russian and eternal friendship of Tatars and Russians.

On 26 February 1913, Ğabdulla Tuqay was hospitalized due to a severe case of tuberculosis. Even in the Klyachkinskaya hospital he never stopped writing poems for Tatar newspapers and magazines. Those poems were both social and philosophical. In March he wrote his literary testament, The First Deed after the Awakening. In hospital Tuqay became interested in Tolstoy's legacy again, devoting to him two verses. He read more about Volga Bulgaria's history as well as all Kazan periods. On 15 April of the same year, Ğabdulla Tuqay died at the age of 27[3] and was buried in Tatar cemetery. 55°45′37″N 49°06′22″E / 55.760223°N 49.106168°E

Legacy

Despite of denial of Tuqay's genius during the early Soviet years, he soon became renowned as the greatest Tatar poet. His name transcended across the arts, with the Tatar State Symphony Orchestra dedicated to Tuqay's name. During the Soviet rule his most cited were his social poems, whereas now the most popular are poems about Tatarstan nature, Tatar national culture, music, history and, of course, the Tatar language. 26 April, his birthday, is celebrated as The Day of Tatar Language, and his poem İ, Tuğan tel (Oh My Mother Tongue!) is the unofficial hymn of the Tatar language.

Excerpt, "Oh My Mother Tongue!"[4]

- Oh, beloved native language

- Oh, enchanting mother tongue!

- You enabled my search for knowledge

- Of the world, since I was young

- As a child, when I was sleepless

- Mother sung me lullabies

- And my grandma told me stories

- Through the night, to shut my eyes

- Oh, my tongue! You have been always

- My support in grief and joy

- Understood and cherished fondly

- Since I was a little boy

- In my tongue, I learned with patience

- To express my faith and say:

- "Oh, Creator! Bless my parents

- Take, Allah, my sins away!"

One of the most famous works after Almaz Monasypov, "In the rhythms of Tuqay" (1975) (Template:Lang-tt-Cyrl, Template:Lang-ru) is written on Tuqay's poems.

References

- ^ pronounced [ɣʌbduˈlɑ tuˈqɑɪ]; full name Ğabdulla Möxämmätğärif ulı Tuqayıv, [ɣʌbduˈlɑ mœxæˌmædɣæˈrif uˈlɯ tuˈqɑjəf]; Tatar Cyrillic: Габдулла Тукай, Габдулла Мөхәммәтгариф улы Тукаев, Jaꞑalif: Ƣabdulla Tuqaj, Template:Lang-ru, Gabdulla Tukay, Gabdulla Mukhammedgarifovich (Mukhammetgarif uly) Tukayev; also spelled Gabdulla Tukai via Russian, Abdullah Tukay via Turkish; English spelling: gub-dool-LAH too-KUY

- ^ "Тукай, Габдулла". Tatar Encyclopaedia (in Tatar). Kazan: The Republic of Tatarstan Academy of Sciences. Institution of the Tatar Encyclopaedia. 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f (in Russian) Тукай. И. Нуруллин. (серия ЖЗЛ). Москва, "Молодая Гвардия", 1977

- ^ Tuqay, Ğabdulla, and Sabırcan Badretdin, trans. http://kitapxane.noka.ru/authors/tuqay/oh_my_mothir_tongui Archived 22 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine