Culture of Belarus: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Lead too long}} |

TaioFerenci (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Belarusian culture is the product of a millennium of development under the impact of a number of diverse factors. These include the [[Geography of Belarus|physical environment]]; the ethnographic background of [[Belarusians]] (the merger of Slavic newcomers with Baltic natives); the [[paganism]] of the early settlers and their hosts; [[Eastern Orthodox Christianity]] as a link to the [[Byzantine literature|Byzantine literary]] and cultural traditions; the country's lack of natural borders; the flow of rivers toward both the [[Black Sea]] and the [[Baltic Sea]]; and the variety of religions in the region ([[Catholicism]], Orthodoxy, [[Judaism]], and [[Islam]]).<ref name=cs>Jan Zaprudnik and Helen Fedor. "Culture", ''A Country Study: Belarus'', Federal Research Division, Library of Congress; Helen Fedor, ed. Research completed June 1995</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/about.html|title=About this Collection - Country Studies|website=Lcweb2.loc.gov|access-date=21 August 2017}}</ref> |

Belarusian culture is the product of a millennium of development under the impact of a number of diverse factors. These include the [[Geography of Belarus|physical environment]]; the ethnographic background of [[Belarusians]] (the merger of Slavic newcomers with Baltic natives); the [[paganism]] of the early settlers and their hosts; [[Eastern Orthodox Christianity]] as a link to the [[Byzantine literature|Byzantine literary]] and cultural traditions; the country's lack of natural borders; the flow of rivers toward both the [[Black Sea]] and the [[Baltic Sea]]; and the variety of religions in the region ([[Catholicism]], Orthodoxy, [[Judaism]], and [[Islam]]).<ref name=cs>Jan Zaprudnik and Helen Fedor. "Culture", ''A Country Study: Belarus'', Federal Research Division, Library of Congress; Helen Fedor, ed. Research completed June 1995</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/about.html|title=About this Collection - Country Studies|website=Lcweb2.loc.gov|access-date=21 August 2017}}</ref> |

||

An early Western influence on Belarusian culture was [[Magdeburg rights|Magdeburg Law—charters]] that granted municipal self-rule and were based on the laws of German cities. These charters were granted in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by grand dukes and kings to a number of cities, including [[Brest, Belarus|Brest]], [[Grodno]], [[Slutsk]], and [[Minsk]]. The tradition of self-government not only facilitated contacts with Western Europe but also nurtured self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and a sense of civic responsibility.<ref name=cs/> |

An early Western European influence on Belarusian culture was [[Magdeburg rights|Magdeburg Law—charters]] that granted municipal self-rule and were based on the laws of German cities. These charters were granted in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by grand dukes and kings to a number of cities, including [[Brest, Belarus|Brest]], [[Grodno]], [[Slutsk]], and [[Minsk]]. The tradition of self-government not only facilitated contacts with Western Europe but also nurtured self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and a sense of civic responsibility.<ref name=cs/> |

||

In 1517-19 [[Francysk Skaryna]] (ca. 1470–1552) translated [[the Bible]] into the vernacular ([[Old Belarusian]]). Under the communist regime, Skaryna's work was vastly undervalued, but in independent Belarus he became an inspiration for the emerging national consciousness as much for his advocacy of the Belarusian language as for his humanistic ideas.<ref name=cs/> |

In 1517-19 [[Francysk Skaryna]] (ca. 1470–1552) translated [[the Bible]] into the vernacular ([[Old Belarusian]]). Under the communist regime, Skaryna's work was vastly undervalued, but in independent Belarus he became an inspiration for the emerging national consciousness as much for his advocacy of the Belarusian language as for his humanistic ideas.<ref name=cs/> |

||

Revision as of 10:10, 28 May 2023

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Belarus |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

This article's lead section may be too long. (April 2023) |

Belarusian culture is the product of a millennium of development under the impact of a number of diverse factors. These include the physical environment; the ethnographic background of Belarusians (the merger of Slavic newcomers with Baltic natives); the paganism of the early settlers and their hosts; Eastern Orthodox Christianity as a link to the Byzantine literary and cultural traditions; the country's lack of natural borders; the flow of rivers toward both the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea; and the variety of religions in the region (Catholicism, Orthodoxy, Judaism, and Islam).[1][2]

An early Western European influence on Belarusian culture was Magdeburg Law—charters that granted municipal self-rule and were based on the laws of German cities. These charters were granted in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by grand dukes and kings to a number of cities, including Brest, Grodno, Slutsk, and Minsk. The tradition of self-government not only facilitated contacts with Western Europe but also nurtured self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and a sense of civic responsibility.[1]

In 1517-19 Francysk Skaryna (ca. 1470–1552) translated the Bible into the vernacular (Old Belarusian). Under the communist regime, Skaryna's work was vastly undervalued, but in independent Belarus he became an inspiration for the emerging national consciousness as much for his advocacy of the Belarusian language as for his humanistic ideas.[1]

From the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries, when the ideas of humanism, the Renaissance, and the Reformation were alive in Western Europe, these ideas were debated in Belarus as well because of trade relations there and because of the enrollment of noblemen's and burghers' sons in Western universities. The Reformation and Counter-Reformation also contributed greatly to the flourishing of polemical writings as well as to the spread of printing houses and schools.[1]

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when Poland and Russia were making deep political and cultural inroads in Belarus by assimilating the nobility into their respective cultures, the rulers succeeded in associating "Belarusian" culture primarily with peasant ways, folklore, ethnic dress, and ethnic customs, with an overlay of Christianity. This was the point of departure for some national activists who attempted to attain statehood for their nation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[1]

The development of Belarusian literature, spreading the idea of nationhood for the Belarusians, was epitomized by the literary works of Yanka Kupala (1882–1942) and Yakub Kolas (1882–1956). The works of these poets, along with several other outstanding writers, became the classics of modern Belarusian literature by writing widely on rural themes (the countryside was where the writers heard the Belarusian language) and by modernizing the Belarusian literary language, which had been little used since the sixteenth century. Post-independence authors in the 1990s continued to use rural themes widely.[1]

Unlike literature's focus on rural life, other fields of culture—painting, sculpture, music, film, and theater—centered on urban reality, universal concerns, and universal values.[1]

Music

The first major musical composition by a Belarusian was the opera Faust by Antoni Radziwiłł. In the 17th century, Polish composer Stanisław Moniuszko composed many operas and chamber music pieces while living in Minsk. During his stay, he worked with Belarusian poet Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich and created the opera Sialianka (Peasant Woman). At the end of the 19th century, major Belarusian cities formed their own opera and ballet companies. The ballet Nightingale by M. Kroshner was composed during the Soviet era.

After World War II, the music focused on the hardships of the Belarusian people or on those who took up arms in defense of the homeland.[3] This was the time period that Anatoly Bogatyrev, the creator of the opera 'In Polesia Virgin Forest', served as the "tutor" of Belarusian composers. The National Academic Theatre of Ballet, in Minsk, was awarded the Prix Benois de la Danse in 1996 as the top ballet company in the world.[4]

Popular Soviet Belarusian music was composed by several prominent bands, many of whom performed Belarusian folk music. Folk rock act Pesniary, formed in 1969 by guitarist Vladimir Mulyavin, became the most popular folk band of the Soviet Union, and often toured over Europe. Pesniary's example inspired Syabry and Verasy to follow their way. The tradition of Belarus as a centre of folk and folk rock music is continued today by Stary Olsa, Vicious Crusade and Gods Tower, among others.

Rock music of Belarus arose in Perestroika times. Bands like Bi-2 (currently living in Russia), Lyapis Trubetskoy, Krama and ULIS were founded in the late 1980s or early 1990s. Though rock music has risen in popularity in recent years, the Belarusian government has suppressed the development of popular music through various legal and economic mechanisms. Because of these restrictions, many Belarusian bands prefer to sign up to Russian labels and to perform in Russia or Ukraine.[5]

Researchers Maya Medich and Lemez Lovas reported in 2006 that "independent music-making in Belarus today is an increasingly difficult and risky enterprise", and that the Belarusian government "puts pressure on ‘unofficial’ musicians - including ‘banning’ from official media and imposing severe restrictions on live performance." In a video interview on freemuse.org the two authors explain the mechanisms of censorship in Belarus.[6]

Since 2004, Belarus has been sending artists to the Eurovision Song Contest.[7]

Dress

The traditional two-piece Belarusian dress originated from the time of Kievan Rus', and continues to be worn today at special functions. Due to the cool climate of Belarus, the clothes were made out of fabrics that provide closed covering and warmth. They were designed with either many threads of different colors woven together or adorned with symbolic ornaments. Belarusian nobles usually had their fabrics imported and chose the colors of red, blue or green. Males wore a shirt and trousers adorned with a belt, while females wore a longer shirt, a wrap-around skirt called a "paniova", and a headscarf. The outfits were also influenced by the dress worn by Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians and other European nations and have changed over time due to improvements in the techniques used to make clothing.[1] Embroidery plays an important role in Belarusian traditions.[8]

World Heritage Sites

Belarus has four World Heritage Sites, with two of them being shared between Belarus and its neighboring countries. The four are the Mir Castle Complex, the Nesvizh Castle, the Białowieża Forest (shared with Poland), and the Struve Geodetic Arc (shared with Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Moldova, Russia, Sweden and Ukraine).[2]

Literature

Belarusian literature began with 11th- to 13th-century religious writing; the work of 12th-century poet Cyril of Turaw is representative.[9] Rhyming was common in these works,[citation needed] which were generally written in Old Belarusian, Latin, Polish or Church-Slavic.[10] By the 16th century, Polotsk resident Francysk Skaryna translated the Bible into Belarusian. It was published in Prague and Vilnius between 1517 and 1525, making it the first book printed in Belarus or anywhere in Eastern Europe.[11] The modern period of Belarusian literature began in the late 19th century; one important writer was Yanka Kupala. Many of the writers at the time, such as Uładzimir Žyłka, Kazimir Svayak, Yakub Kolas, Źmitrok Biadula and Maksim Haretski, wrote for a Belarusian language paper called Nasha Niva, published in Vilnius. After (Eastern) Belarus was incorporated into the Soviet Union, the government took control of Belarusian culture,[vague] and until 1939 free development of literature occurred only in the territories incorporated into Poland (Western Belarus).[11] Several poets and authors went into exile after the Nazi occupation of Belarus, not to return until the 1960s.[11] In post-war literature, the central topic was World War II (known in Belarus as the Great Patriotic War), that had particularly left particularly deep wounds in Belarus (Vasil’ Bykaw, Ales Adamovich etc.); the pre-war era was also often depicted (Ivan Melezh). A major revival of the Belarusian literature occurred in the 1960s with novels published by Vasil’ Bykaw and Uladzimir Karatkievich.

Theater

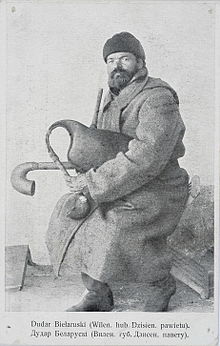

Belarusian theater also began to gain popularity in the early 1900s, with Ihnat Bujnicki considered to be its founder.[12] However, some prominent plays like Dunin-Marcynkevič’s Pinskaja Šliachta [Pinsk Gentry] were written in the 19s century. One of Belarus's most famous plays, Paulinka (written by Yanka Kupala), was performed in Siberia for the Belarusians who were being sent to the region. [3] Documentation of Belarusian folk music stretches back to at least the 15th century. Prior to that, skomorokhs were the major profession for musicians. A neumatic chant, called znamenny, from the word znamena (Russian: знамёна - signs), meaning sign or neume, was used until the 16th century in Orthodox church music, followed by two hundreds of stylistic innovation that drew on the Renaissance and Protestant Reformation. In the 17th century, Partesnoe penie, part singing, became common for choruses, followed by private theaters established in cities like Minsk and Vitebsk. Popular music groups that came from Belarus include Pesniary, Dreamlin and NRM. Currently, there are 27 professional theater groups touring in Belarus, 70 orchestras, and 15 agencies that focus on promoting concerts.

In 2005, playwrights Nikolai Khalezin and Natalya Kolyada founded the Belarus Free Theatre, an underground theatre project dedicated to resisting pressure and censorship by government of Belarus. The group performs in private apartments and at least one such performance was broken up by special forces of the Belarusian police[13] The Belarus Free Theatre has attracted the support of notable Western writers such as Tom Stoppard, Edward Bond, Václav Havel, Arthur Kopit and Harold Pinter.

Puppet theatre

Batlejka, an amateur puppet theatre, became popular in Belarus in the 16th century, with the peak of its popularity falling on the 18-19th centuries. The first professional puppet theatre, the Belarusian State Puppet Theatre (Template:Lang-be) was established in Homiel in 1938.[14]

Russian impact

Following the Partitions of Poland, Imperial Russia enacted a policy of de-polonisation of the Ruthenians. However, even after many cases when the Belarusian peoples were subjected to what some call Russification, it was clear that this created a distinct ethnicity and a distinct culture that was neither Polish nor Russian. In 1897 census most of the population referred to their language as Belarusian rather than Ruthenians (and interpreted as Russian by Tsarist authorities), as they did during Polish rule.

It was the 20th century that fully allowed Belarus to show its culture to the world. Notable Belarusian poets and writers included Yanka Kupala, Maksim Bahdanovič, Vasil’ Bykaw, and Uladzimir Karatkievich. Also helped was the korenizatsiya policy of the Soviet Union which encouraged local level nationalism. The Belarusian language was numerously reformed to fully represent the phonetics of a modern speaker. However, some contemporary nationalists find that the Russian influence has taken its toll too much. At present the Russian language is being used in official business and in other sections of Belarusian society.

Festivals

The Belarusian government sponsors many annual cultural festivals: Slavianski Bazaar in Vitebsk; "Minsk Spring"; "Slavonic Theatrical Meetings"; International Jazz Festival; National Harvesting Festival; "Arts for Children and Youth"; Competition of Youth Variety Show Arts; "Muses of Nesvizh"; "Mir Castle"; and the National Festival of the Belarusian Song and Poetry. These events showcase talented Belarusian performers, whether it is in music, art, poetry, dance or theater. At these festivals, various prizes named after Soviet and Belarusian heroes are awarded for excellence in music or art. The contemporary nationalists argue that most of these sponsored events have nothing to do with the Belarusian culture, let alone the culture as such, however all the events are subject to the expertise of the Belarusian Ministry of Culture. Several state holidays, like Independence Day or Victory Day draw big crowds and include various displays such as fireworks and military parades. Most of the festivals take place in Vitebsk or Minsk. [4]

Sport

From the 1952 Helsinki Games until the end of the Soviet era, Belarus competed in the Olympic Games as part of the Soviet Olympic squad. During the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, Belarus competed as part of the Unified Team. The nation's athletes competed in an Olympic Games as Belarusians for the first time during the 1994 Lillehammer Games. Belarus has won a total of 52 Olympic medals; 6 gold, 17 silver and 29 bronze. Belarus's National Olympic Committee has been headed by President Lukashenko since 1997; he is the only head of state in the world to hold this position.[5][15]

The national football team has never qualified for a major tournament; however, BATE Borisov has played in the Champions League. Receiving heavy sponsorship from the government, ice hockey is the nation's most popular sport. The national hockey team finished fourth at the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics following a memorable upset win over Sweden in the quarterfinals, and regularly competes in the World Championships, often making the quarterfinals. Numerous Belarusian players are present in the Kontinental Hockey League in Eurasia, particularly for Belarusian club HC Dinamo Minsk, and several have also played in the National Hockey League in North America. Darya Domracheva is a leading biathlete whose honours include three gold medals at the 2014 Winter Olympics.[16]

Tennis player Victoria Azarenka became the first Belarusian to win a Grand Slam singles title at the Australian Open in 2012.[17] She also won the gold medal in mixed doubles at the 2012 Summer Olympics with Max Mirnyi, who holds ten Grand Slam titles in doubles. Aryna Sabalenka won the 2018 Wuhan Open singles tournament.

Other notable Belarusian sportspeople include cyclist Vasil Kiryienka, who won the 2015 Road World Time Trial Championship, and middle-distance runner Maryna Arzamasava, who won the gold medal in the 800m at the 2015 World Championships in Athletics.

Belarus is also known for its strong rhythmic gymnasts. Noticeable gymnasts include Inna Zhukova, who earned silver at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Liubov Charkashyna, who earned bronze at the 2012 London Olympics and Melitina Staniouta, Bronze All-Around Medalist of the 2015 World Championships. The Belorussian senior group earned bronze at the 2012 London Olympics.

Andrei Arlovski, who was born in Babruysk, Byelorussian SSR, is a current UFC fighter and the former UFC heavyweight champion of the world.

Belarus featured a men's national team in beach volleyball that competed at the 2018–2020 CEV Beach Volleyball Continental Cup.[18]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Jan Zaprudnik and Helen Fedor. "Culture", A Country Study: Belarus, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress; Helen Fedor, ed. Research completed June 1995

- ^ "About this Collection - Country Studies". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Theatre". The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007.

- ^ Virtual Guide to Belarus - Classical Music of Belarus. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ^ "Belarus election: Blacklisted bands play in Poland". Freemuse.org. 18 March 2013. Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Maya Medich & Lemez Lovas: Music censorship in Belarus". Freemuse.org. 18 March 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ National State Teleradiocompany Page on the 2004 Belarusian entry to the Eurovision Song Contest Archived February 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Published 2004. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ^ "Seeing Red (And White): Belarus Shows Its Colors In Ribbon Campaign". RFERL. 6 December 2014.

- ^ "Old Belarusian Poetry". Virtual Guide to Belarus. 1994. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ UNESCO Preservation of Belarusian Literary Heritage Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c Belarus - Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ "Ігнат Буйніцкі: бацька беларускага тэатра" [Ihnat Bujnicki: the father of the Belarusian theatre]. zbsb.org (in Belarusian). Retrieved 2021-12-29.

- ^ "Arrests after the second act". Signandsight.com. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ^ "Belarus | World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts". 24 March 2016. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ "NOC of Belarus". Archived from the original on 17 March 2016.

- ^ "Darya DOMRACHEVA". www.olympic.org.

- ^ "Queen Victoria takes the throne determined to court further success". The Sydney Morning Herald. 29 January 2012.

- ^ "Continental Cup Finals start in Africa". FIVB. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

External links

- Literarure

- Belarusian Writers And The Soviet Past

- Belarus, Ukraine, Russia React To Alexievich’s Nobel Prize

- “Second-Hand” Coverage: Alexievich's Nobel Prize In The Belarus' Media

- Art

- Contemporary Belarusian Art and Painting

- National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus

- Performance biennial International

- Travelling