Allan MacNab: Difference between revisions

m clean up pipe links |

|||

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca/scripts/large.php?accessnumber=I-796.1&Lang=1&imageID=223722 Photograph: Sir Allan McNab in 1861. McCord Museum] |

*[http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca/scripts/large.php?accessnumber=I-796.1&Lang=1&imageID=223722 Photograph: Sir Allan McNab in 1861. McCord Museum] |

||

*[ |

*[https://aims.archives.gov.on.ca/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/DESCRIPTION_WEB/WEB_DESC_DET?SESSIONSEARCH&exp=sisn%20164 Allan Napier MacNab fonds], Archives of Ontario |

||

{{Members of the Family Compact}} |

{{Members of the Family Compact}} |

||

Revision as of 12:55, 21 July 2023

Allan Napier MacNab | |

|---|---|

Portrait in 1853 by Théophile Hamel | |

| Joint Premier of the Province of Canada | |

| In office 11 September 1854 – 24 May 1856 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governor General | Sir Edmund Walker Head |

| Preceded by | Francis Hincks |

| Succeeded by | John A. Macdonald |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada for Wentworth County | |

| In office 1830–1834 | |

| Monarch | William IV |

| Lieutenant Governor | Sir John Colborne |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada for Hamilton | |

| In office 1834–1841 | |

| Monarchs | William IV (1830–1837) Victoria (1837–1901) |

| Lieutenant Governor | Sir John Colborne (1828–1836) Sir Francis Bond Head (1836–1838) Sir George Arthur (1838–1839) Lord Sydenham (1839-1841) |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada for Hamilton | |

| In office 1841–1857 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governors General | Lord Sydenham (1841) Sir Charles Bagot (1842–1843) Sir Charles Metcalfe (1843–1845) Lord Cathcart (1845–1847) Lord Elgin (1847–1854) Sir Edmund Walker Head (1854–1861) |

| Preceded by | New position |

| Succeeded by | Isaac Buchanan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 February 1798 Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada |

| Died | 8 August 1862 (aged 64) Hamilton, Canada West |

| Political party | Tory |

| Profession | Lawyer and businessman |

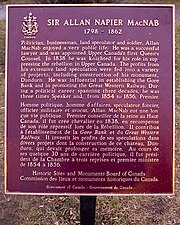

Sir Allan Napier MacNab, 1st Baronet (19 February 1798 – 8 August 1862) was a Canadian political leader, politician, land speculator and property investor/builder, lawyer, soldier, and militia commander who served in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada twice (representing a different county - Wentworth and Hamilton - each time), the Legislative Assembly for the Province of Canada once, and served as joint Premier of the Province of Canada from 1854 to 1856. MacNab was "likely the largest land speculator in Upper Canada during his time" as mentioned both in his official biography in retrospect and in 1842 by Sir Charles Bagot.[1]

MacNab is perhaps best known either for his relation to Queen Camilla, the current Queen of Canada (one of MacNab's grandchildren married Alice Keppel, great-grandmother of Camilla) or for the construction of an extremely opulent and influential neoclassical mansion in Hamilton, Ontario called Dundurn Castle. MacNab was both the castle's first and only baronet, and Queen Camilla is the current Royal Patron of her extended antecedent's "castle" currently.

MacNab was an "Elite Member" of the Family Compact in Upper Canada. He briefly shared a military regiment (the 49th Regiment of Foot) with another elite member (James FitzGibbon) in the War of 1812. MacNab would be left out of the regiment following regimental cuts after the War of 1812, and would find employment in the law office of another Family Compact members grandfather - George D'Arcy Boulton (aka D'Arcy Boulton Sr.)[2]

Early life

He was born in Newark[3] (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) to Allan MacNab and Anne Napier (daughter of Captain Peter William Napier, R.N., the commissioner of the port and harbour of Quebec). When MacNab was a one year old, he was baptized in the Anglican church in St. Mark's Parish of Newark.[3] His father was a lieutenant in the 71st Regiment and the Queen's Rangers under Lt-Col. John Graves Simcoe. After the Queen's Rangers were disbanded, the family moved around the country in search of work and eventually settled in York (now Toronto), where MacNab was educated at the Home District Grammar School.

Military career

War of 1812

As a fourteen-year-old boy, he fought in the War of 1812. He probably served at the Battle of York and certainly as the point man in the Canadian forlorn hope that headed the Anglo-Canadian assault on Fort Niagara. The 20 local men eliminated two American pickets of 20 men each with the bayonet before taking part in the final assault. Captain Kerby, of the Incorporated Militia Battalion, was reportedly the first man into the fort.[4]

Upper Canada Rebellion, 1837

Before the Rebellion broke out, MacNab both argued for increased American immigration as "they are a useful and enterprising people and if admitted would be of great advantage to the country" in 1837. Again before the Rebellion, MacNab was appointed as Lieutenant-Colonel of the 4th Regiment of the Gore militia in May 1830, partly through the influence of the Chisholm family of Oakville.[5]

MacNab opposed the reform movement in Upper Canada that was led by William Lyon Mackenzie. When Mackenzie led the Upper Canada Rebellion in 1837, MacNab was part of the force of British regular troops and Upper Canada militia that moved against Mackenzie at Montgomery's Tavern in Toronto on 7 December, dispersing Mackenzie's rebels in less than an hour.

MacNab in turn for the victory at Montgomery's Tavern would be awarded sole command of troops sent to London District by Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head and led a militia of his own against the rebels marching towards Toronto from London, led by Charles Duncombe. Duncombe's men also dispersed when they learned that MacNab was waiting for them, but the quality of MacNab's leadership was nonetheless regarded as "mixed". There were "extreme problems" in communication, procuring supplies, and controlling the volunteers, along with MacNab ignoring basic operational procedures. MacNab was given 250 troops but there would ultimately be some 1500 men assembled total, as MacNab argued "as early as December 14".[6]

Mackenzie would flee to the United States following his defeat at the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern on December 7, and return to Canada on 13 December, occupying Navy island, with increased American sympathy. MacNab would be dispatched by Sir Bond Head on Christmas Day (December 25) 1837 to command the troops in Niagara with support from both naval forces and regular officers. MacNab would see himself alternating between "drilling or dining" for about 4 to 5 days as "supplies and billeting were inadequate and orders were vague" regarding command centers in Toronto and Montreal. Moreover, there were contradictory reports coming to both Head and MacNab regarding the amount of American supplies and the strength and morale of Mackenzie's new rebel force, and Head refused to sanction Navy island but offered no other alternatives. There were some 2000 raw and reckless volunteers amassed as troops by December 29.[7]

December 29 would prove to be important to MacNab as two attacks happened against Mackenzie's forces on 29 December under MacNab's command: a dawn attack and a dusk attack. The first attack would prove how little discipline the officers had under MacNab, how little control MacNab had over them, and how weak the line of command was, and the second attack would prove to show how reckless MacNab could be if his position as "commander" was stood up. The dawn (first) attack would not be sanctioned or ordered by MacNab and was the result of a group of particularly bibulous officers and the event would nearly end in disaster. The second (dusk) attack however would both end in disaster and be the result of MacNab's order. MacNab and Captain Andrew Drew, a retired officer of the Royal Navy, commanding a party of militia, acting on information and guidance from Alexander McLeod, attacked Mackenzie's supply ship at Navy Island, an American ship called the Caroline. The sinking of the SS Caroline would happen in American waters and would see an American citizen killed - the stakes became raised and the reaction was swift and immediate. The event became known as the Caroline affair. The affair would see MacNab indicted for murder in Erie County, New York, and subsequently replaced by Colonel Hughes, taking MacNab's post of Commander in Niagara. However, before leaving the frontier MacNab would protest that Hughes would be the one to receive "all the credit" whilst MacNab and the militia had done "all the drudgery". Later, MacNab would see himself quit the Niagara frontier on January 14, 1838. There were some 3500 troops amassed only 4 days before. Ironically, on the evening of January 14, Mackenzie and his force slipped off the island and Hughes (MacNab's replacement) would be occupying Navy island as MacNab was lobbying in Toronto for his command position back.[8]

It is noted during the Rebellions that MacNab appreciated "degrees of involvement" with rebel forces in that he jailed "only the rebel leaders" under his own initiative and saw the "common followers" of the rebels as people who were "deceived", even promising clemency to some. MacNab also shared a common philosophy in his own troops, believing that officers earn the respect of their subordinates "not only through courage in war but also by tempering strict justice with kindness and approachability off the battlefield".[9]

In 1838, Macnab was knighted for his zeal in suppressing the rebellion.

In 1860, Macnab was appointed an honorary colonel in the British army, and aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria.[10]

Legal and business career

After his service in the War of 1812, MacNab studied law in Toronto under (at the time) Judge George D'Arcy Boulton, where it was noted that MacNab "took nearly twice the average time to qualify at the bar was a result of his inadequate education and his preference for active work".[11] MacNab was admitted to the bar in 1824, and called to the bar in 1826.[12][13] In 1826, MacNab moved from York to Hamilton, where he established a successful law office, but it was chiefly by land speculation that he made his fortune. There was no Anglican church in Hamilton yet, so MacNab attended a Presbyterian church until Christ Church was established in 1835.[14]

A successful entrepreneur as well as politician, MacNab, with Glasgow merchant Peter Buchanan, was responsible for the construction of the Great Western Railway of Ontario.[15] MacNab also served on several boards, including as a board member of the Beacon Fire and Life Insurance Co. of London alongside prominent financier Thomas Clarkson.[16]

Following an amount of "liberal credit" rewarded from the Bank of Upper Canada regarding legislative assistance given by MacNab, and his own cash reserves, MacNab sought to own land. By May 1832, MacNab would own "some 2000 acres of wild land in London, Gore, and Newcastle districts". The amount would increase and by 1835 MacNab had "cornered much of the best land in the centre of expanding Hamilton". MacNab's land holdings would fluctuate often, and their total value at any one time is unknown, but in a suggestion of just how massive the amounts of land and sales were, Charles Bagot stated in 1842 that MacNab was "a huge proprietor of land - perhaps the largest in the country".[17] This is stated in MacNab's biography as "probably true".

MacNab's land purchases (especially in the early 1830s) would place financial strain on MacNab initially, but it would prove to be worth it in the long run. In one scenario, MacNab would purchase a piece of land in November 1832 located in Burlington Heights from J. S. Cartwright for 2500 pounds - 500 more than MacNab wanted - where MacNab would see the "symbol of his social aspirations" built: the opulent and luxury 72-room Dundurn Castle. Ironically, on the day of the sale for the land, between 5000 to 10000 pounds of fire damage would ravage MacNab's Hamilton projects.[18]

MacNab could prove to be unethical but effective with his business career: case in point is MacNab being some three years behind in payments for an extremely important creditor named Samuel Peters Jarvis, and after some three years time MacNab stated he would not pay Jarvis back for this credit as Jarvis "owed MacNab for past services". Whether this is true or not is unknown, but Jarvis simply stated MacNab as one word for this - villain.[19]

Political career

MacNab represented Hamilton in Parliament from 1830 until his death in 1862, first in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada (1830–1840), then in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada (1841–1860), and finally in the Legislative Council of the Province of Canada representing the Western Division (1860–1862).[20] He was joint Premier of the province from 1854 to 1856.

In 1829, MacNab refused to testify before a House of Assembly committee which was investigating the hanging of an effigy of Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne, chaired by Reformer W. W. Baldwin. MacNab would subsequently be sentenced to jail for 10 days by the House of Assembly, following apparent "prodding" from William Lyon Mackenzie. MacNab returned to the public as a "Tory martyr", and effectively utilized/exploited this image to defeat the Reformers in Wentworth County and secure the political victory for both he and John Willson.[21]

In April 1833, MacNab would secure the appointment of the land registrar of Wentworth for his brother David Archibald. This was important as whoever controlled this office could “quietly acquire choice and undeveloped land in the Wentworth are without a need for a public auction”. This benefitted MacNab as a land speculator as "he had gained a seemingly impregnable hold over Wentworth’s land development and, as a result, a firm grip on the county’s commercial and political future" due to appointing his brother.[22]

MacNab came under public scrutiny when he was ousted as president of the Desjardins Canal Company in 1834, after having mortgaged a large block of personal land as security for a government loan to the company in 1832.[23]

MacNab committed a breach of privilege and was arrested by the sergeant-of-arms during the 10th Parliament of Upper Canada after a motion by the legislative assembly. MacNab retaliated by seconding a motion in December 1831 which was accusing William Lyon Mackenzie of breach of privilege and motioned for him to be expelled from the house on the grounds of libel. The motion failed after Tory legislators feared the political backlash of supporting an obscure parliamentary privilege.[24] This would be the first of five expulsions, MacNab active in all of them.[25]

MacNab acted as a "spearhead" in the political attacks against Mackenzie (because of his involvement in all 5 expulsions) and this would be beneficial for MacNab, causing him to gain power within the Assembly and maintain a solid link with the members of so-called "Tory York". This would be beneficial for the Tories in Canada regarding their control of power in the Upper Canadian commercial and economic sectors, as MacNab acted as bridge for all members to communicate with each other, whereas previously there was only "intra-party maneuverings". This "intra-party struggle" was most evident and apparent when it came to banks and land speculation.[26]

MacNab was a "Compact Tory" - a supporter of the Family Compact which had controlled Upper Canada prior to the union of the Canadas.[3][27] In the first Parliament of the new Province of Canada, he supported the principle of union, but was an opponent of the Governor General, Sydenham, and his policy of creating a government with a broad base of moderate supporters in the Assembly. He opposed the policy of the "Ultra Reformers" to implement responsible government.[28]

MacNab only partly encompassed the Tory ideology in Canada and was not a religious elitist: MacNab supported all denominations (plus Catholics) in having an equal share to the proceeds from the clergy reserves, MacNab often attended a Presbyterian church whilst being Anglican, MacNab married a Catholic in his second marriage, and opposed Orangeman Ogle Robert Gowan partly because of how strong his Protestant stance was.[29]

Although MacNab would receive the title of "Baronet" through a baronetcy patronage by Sir Edmund Walker Head in July 1856, the action was nearly entirely the result of Head's "sympathetic recommendation" over any sort of rewarded action.[30]

When Parliament met at Montreal, MacNab took apartments there at Donegana's Hotel.[citation needed]

Family

MacNab was married twice. His first wife was Elizabeth Brooke, who died 5 November 1826, possibly of complications following childbirth. Together, they had two children.

He married his second wife, Mary, who died 8 May 1846 and was a Catholic; she was the daughter of John Stuart, Sheriff of the Johnstown District, Ontario. The couple's two daughters, Sophia and Minnie, were raised as Catholics.[3]

The couple's elder daughter, Sophia, was born at Hamilton. She married at Dundurn Castle, Hamilton, on 15 November 1855, William Keppel, Viscount Bury, afterwards the 7th Earl of Albemarle, who died in 1894. Sophia was the mother of Arnold Keppel, 8th Earl of Albemarle (born in London, England, 1 June 1858), and of eight other children. One of her sons, the Honourable Derek Keppel, served as Equerry to The Duke of York after 1893 and was in Canada with His Royal Highness, in 1901 at 53 Lowndes Square, London, S. W., England.[31] Another of her sons was married to Alice Keppel, a mistress of Edward VII, and great grandmother of Queen Camilla, wife of Charles III.

Death

MacNab died at his home, Dundurn Castle, in Hamilton. His deathbed conversion to Catholicism caused a furore in the press in the following days. The Toronto Globe and the Hamilton Spectator expressed strong doubts about the conversion, and the Anglican rector of Christ Church declared that MacNab died a Protestant.[14]

However, MacNab's Catholic baptism is recorded at St. Mary's Cathedral in Hamilton, at the hands of John Farrell, Bishop of Hamilton, on 7 August 1862.[3]

When the 12th Chief of Clan Macnab died, he bequeathed all his heirlooms to MacNab, whom he considered the next Chief. When the latter's son was killed in a shooting accident in Canada, the position of Chief of Clan Macnab passed to the Macnabs of Arthurstone.

Legacy

MacNab Street and Sir Allan MacNab Secondary School in Hamilton, Ontario are both named after him.[32]

Dundurn Castle, his stately Italianate style home in Hamilton, is open to the public.

A ship was named Sir Allan MacNab and was sturdily built in Canada but was not altogether designed for speed. The master in 1855 was Captain Cherry, and the tonnage of the ship was 840, then quite large.

References

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Dooner, Alfred (1942–1943), "The Conversion of Sir Allan MacNab, Baronet (1798–1862)", Canadian Catholic Historical Association Report, 10: 47–64

- ^ Dalby, Paul (29 June 2006). "MacNab's 'castle' home makes a grand statement". Toronto Star (Canada). Toronto Star Newspapers Ltd. p. H06. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "No. 22403". The London Gazette. 13 July 1860. p. 2614.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 566.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ a b King, Nelson (5 August 2009). "Alan Napier MacNab". Soldier, Statesman, and Freemason Part 3. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Smith, Edward (2007). ""All My Politics Are Railroads"". Dundurn Castle: Sir Allan MacNab and his Hamilton Home. James Lorimer & Company Ltd. pp. 75–84. ISBN 978-1-55028-988-6.

The result was that Canadian directors like MacNab had control over the day-to-day work of the railroad and seeing to political backing in Canada, while overall financial control resided in England.

- ^ Mights' Greater Toronto City Directory (1856) page 159

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Dictionary of Hamilton Biography (Vol I, 1791–1875); Thomas Melville Bailey (W.L. Griffin Ltd), 1981, Page 143

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Kilbourn, William (30 June 2008). "The Firebrand: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion in Upper Canada". Dundurn. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-77070-324-7. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Baskerville, Peter (1976). "MacNab, Sir Allan Napier". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IX (1861–1870) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Paul G. Cornell, Alignment of Political Groups in Canada, 1841-67 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962; reprinted in paperback 2015), pp. 6, 7, 10, 93–97.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Biography – MacNAB, Sir ALLAN NAPIER – Volume IX (1861-1870) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 224.

- ^ Manson, Bill (2003). Footsteps in Time: Exploring Hamilton's heritage neighbourhoods. North Shore Publishing Inc. ISBN 1-896899-22-6.

Sources

- Donald R. Beer, Sir Allan Napier MacNab (Hamilton, Ontario, 1984)

External links

- Photograph: Sir Allan McNab in 1861. McCord Museum

- Allan Napier MacNab fonds, Archives of Ontario

- 1798 births

- 1862 deaths

- Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom

- Canadian baronets

- Canadian Knights Bachelor

- Premiers of the Province of Canada

- Members of the Executive Council of the Province of Canada

- Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada from Canada West

- Members of the Legislative Council of the Province of Canada

- People from Niagara-on-the-Lake

- Canadian Roman Catholics

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism

- Canadian people of Scottish descent

- Upper Canada Rebellion people

- 49th Regiment of Foot officers

- British Army personnel of the War of 1812

- Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- Speakers of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada