Fazil Iskander: Difference between revisions

ParadaJulio (talk | contribs) →External links: ++ |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

[[File:Abkhazia 10 apsar Ag 2009 Iskander b.jpg|thumb|right|249px|Reverse side of a 10 [[Abkhazian apsar|apsar]] [[commemorative coin]] minted on 6 May 2009 to celebrate Fazil Iskander's 80th birthday.]] |

[[File:Abkhazia 10 apsar Ag 2009 Iskander b.jpg|thumb|right|249px|Reverse side of a 10 [[Abkhazian apsar|apsar]] [[commemorative coin]] minted on 6 May 2009 to celebrate Fazil Iskander's 80th birthday.]] |

||

'''Fazil Abdulovich Iskander'''{{efn|{{lang-ru|Фази́ль Абду́лович Исканде́р}}; {{lang-ab|Фазиль Абдул-иԥа Искандер|Fazil Abdul-ipa Isk’ander}}}} (6 March 1929 – 31 July 2016) was a Soviet and Russian<ref name="rg">"There's no doubt I'm a Russian writer who praised Abkhazia a lot. Unfortunately, I haven't written anything in the Abkhaz language. The choice of Russian culture was principal to me." ''[https://rg.ru/2011/03/04/iskander.html It is stifling to live without conscience] interview in [[Rossiyskaya Gazeta]]'', March 4, 2011 (in Russian)</ref> writer and poet known in the former [[Soviet Union]] for his descriptions of [[Caucasus|Caucasian]] life. He authored various stories, including "Zashita Chika", which features a crafty and |

'''Fazil Abdulovich Iskander'''{{efn|{{lang-ru|Фази́ль Абду́лович Исканде́р}}; {{lang-ab|Фазиль Абдул-иԥа Искандер|Fazil Abdul-ipa Isk’ander}}}} (6 March 1929 – 31 July 2016) was a Soviet and Russian<ref name="rg">"There's no doubt I'm a Russian writer who praised Abkhazia a lot. Unfortunately, I haven't written anything in the Abkhaz language. The choice of Russian culture was principal to me." ''[https://rg.ru/2011/03/04/iskander.html It is stifling to live without conscience] interview in [[Rossiyskaya Gazeta]]'', March 4, 2011 (in Russian)</ref> writer and poet known in the former [[Soviet Union]] for his descriptions of [[Caucasus|Caucasian]] life. He authored various stories, including "Zashita Chika", which features a crafty and likeable young boy named "Chik", but is probably best known for the picaresque novel ''Sandro of Chegem'' and its sequel ''The Gospel According to Chegem''. |

||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

Revision as of 08:00, 31 July 2023

Fazil Iskander | |

|---|---|

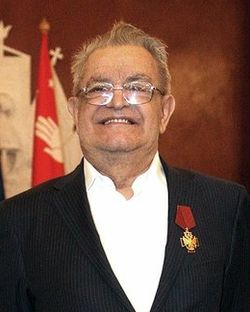

Iskander being awarded the Order of Merit for the Fatherland, 2010 | |

| Born | Искандер, Фазиль Абдулович Fazil Abdulovich Iskander 6 March 1929 Sukhumi, SSRA, TSFSR, USSR |

| Died | 31 July 2016 (aged 87) Peredelkino, Russia |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist, poet |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Genre | memoirs, satire, parable, essays, aphorism |

| Notable works | Sandro of Chegem |

| Notable awards |

|

| Relatives | Abdul Ibragimovich Iskander (father); Leili Khasanovna Iskander (mother); Feredun Abdulovich Iskander (brother); Giuli Abdulovna Iskander (sister) |

| Signature | |

| |

Fazil Abdulovich Iskander[a] (6 March 1929 – 31 July 2016) was a Soviet and Russian[1] writer and poet known in the former Soviet Union for his descriptions of Caucasian life. He authored various stories, including "Zashita Chika", which features a crafty and likeable young boy named "Chik", but is probably best known for the picaresque novel Sandro of Chegem and its sequel The Gospel According to Chegem.

Biography

Early life

Fazil Abdulovich Iskander was born in 1929 in the cosmopolitan port city of Sukhumi, Georgia (then part of the USSR) to an Iranian father (Abdul Ibragimovich Iskander) and an Abkhazian mother (Leili Khasanovna Iskander).[2][3] His father was deported to Iran in 1938 and sent to a penal camp where he died in 1957.[4] His father was the victim of Joseph Stalin's deportation policies of the national minorities of the Caucasus.[2] As a result, Fazil and his brother Feredun and his sister Giuli were raised by his mother's Abkhazian family.[2][4] Fazil was only nine years old at that time.[5][6]

Career

The most famous intellectual of Abkhazia,[citation needed] he first became well known in the mid-1960s along with other representatives of the "young prose" movement like Yury Kazakov and Vasily Aksyonov, especially for what is perhaps his best story,[7] Sozvezdie kozlotura (1966), variously translated as "The Goatibex Constellation," "The Constellation of the Goat-Buffalo," and "Constellation of Capritaurus." It is written from the point of view of a young newspaperman who returns to his native Abkhazia, joins the staff of a local newspaper, and is caught up in the publicity campaign for a newly produced farm animal, a cross between a goat and a West Caucasian tur (Capra caucasica); a "remarkable satire of Lysenko's genetics and Khrushchev's agricultural campaigns, it was harshly criticized for showing the Soviet Union in a bad light."[8][9]

He is probably best known in the English speaking world for Sandro of Chegem, a picaresque novel that recounts life in a fictional Abkhaz village from the early years of the 20th century until the 1970s, which evoked praise for the author as "an Abkhazian Mark Twain."[10] Mr. Iskander's humor, like Mark Twain's, has a tendency to sneak up on you instead of hitting you over the head.[10] This rambling, amusing and ironic work has been considered as an example of magic realism, although Iskander himself said he "did not care for Latin American magic realism in general".[11] Five films were made based upon parts of the novel.[12]

Iskander distanced himself from the Abkhaz secessionist strivings in the late 1980s and criticised both Georgian and Abkhaz communities of Abkhazia for their ethnic prejudices. [citation needed] He warned that Abkhazia could become a new Nagorno-Karabakh. [citation needed] Later Iskander resided in Moscow and was a writer for the newspaper Kultura.[13]

On 3 September 2011, a statue of Iskander's literary character Chik was unveiled on Sukhumi's Muhajir Quay.[14]

Family

Iskander had been married to a Russian poet Antonina Mikhailovna Khlebnikova since 1960. In 2011 the couple published a book of poems entitled Snow and Grapes to celebrate their golden wedding anniversary.[1] They had one son and one daughter.

Death

Iskander died in his home on 31 July 2016 in Peredelkino, aged 87.[15][16][17][18]

Quotes

"Perhaps the most touching and profound characteristic of childhood is an unquestioning belief in the rule of common sense. The child believes that the world is rational and hence regards everything irrational as some sort of obstacle to be pushed aside. . . . The best people, I think, are those who over the years have managed to retain this childhood faith in the world's rationality. For it is this faith which provides man with passion and zeal in his struggle against the twin follies of cruelty and stupidity." (The Goatibex Constellation)

„all serious Russian and European literature is an endless commentary on the gospel.“

(„Reflections of a Writer“ by Fazil Iskander) [19]

Awards and prizes

- USSR State Prize (1989) - for his novel "Sandro of Chegem"[20][21]

- Alfred Toepfer foundation's Pushkin Prize (1992)[22]

- State Prize of the Russian Federation in Literature and Arts (1993, 2013)[23][24]

- Triumph Prize (1999).[25]

- Order of Honour and Glory, 1st class (Abkhazia, 18 June 2002) [26]

- Order of Merit for the Fatherland;)[27]

- 2nd class (29 September 2004)

- 3rd class (3 March 1999)

- 4th class (13 March 2009, presented on February 17, 2010.[28])

- Honorary Member of Russian Academy of Arts

- Yasnaya Polyana Literary Award (2011) - for the novel "Sandro of Chegem"[29]

- Ivan Bunin literary award (2013)

In 2009, Bank of Abkhazia issued a commemorative silver coin from the series "Outstanding Personalities of Abkhazia", dedicated to Fazil Iskander denomination of 10 apsaras. [citation needed]

Already after the writer's death, the Fazil Iskander International Literary Prize was established in Russia in three nominations: prose, poetry and screenplay based on the works of Iskander. The Fazil Iskander International Literary Award is now in its sixth year. [30] was established on August 3, 2016 by the Russian branch of the International Russian PEN Center.

Works

Works in English translation

- Forbidden Fruit and Other Stories, Central Books LTD, 1972.

- The Goatibex Constellation, Ardis, 1975.

- Iskander, Fazil; Lindsey, Byron; Burlingame, Helen (1976). "The Goatibex Constellation". Books Abroad. 50 (4): 905. doi:10.2307/40131179. JSTOR 40131179. Retrieved 2022-09-20.

- Contemporary Russian Prose (English and Russian Edition), 1980 ISBN 978-0-882-33596-4

- Sandro of Chegem, Vintage Books, 1983. ISBN 978-0-394-71516-2

- The Gospel According to Chegem, Vintage Books, 1984.ISBN 978-0-394-72377-8

- Chik and His Friends, Ardis 1985.

- Bolshoi den bolshogo doma: Rasskazy, 1986

- Iskander, Fazil (1988). "Fooling with words". Index on Censorship. 17 (5): 19–20. doi:10.1080/03064228808534413. S2CID 146216870. Retrieved 2022-09-20.

- Rabbits and Boa Constrictors, Ardis, 1989. (Co-authored with Ronald E. Peterson) ISBN 978-0-882-33557-5

- The Old House Under the Cypress Tree, Faber and Faber, 1996.

- The Thirteenth Labour of Hercules, Raduga, 1997.

- Rasskazy, povestʹ, skazka, dialog, ėsse, stikhi (Zerkalo) (Russian Edition), 1999 ISBN 978-5-891-78090-3

- Parom (Russian Edition), 2004 ISBN 978-5-941-17138-5

- Kozy i Shekspir: [Goats and Shakespear: ], Russian Edition, 2008

- Put' iz Variag v Greki (The Road from the Varangians to the Greeks), Russian Edition 2008 ISBN 978-5-969-10305-4

- Zoloto Vil'gel'ma: Povesti, Rasskazy (Gold of Vilgel'm: Stories, tales), 2010.

- L'energia della vergogna (Italian Edition), 2014.

- The Mystery of Conscience, 2016. ISBN 978-1-329-31637-9

- Departures, 2016 ISSN 1066-999X

- Sandró de Cheguem (Narrativa) (Spanish Edition), 2017 ISBN 978-8-415-50938-7

- Druzia-priiateli/Detstvo Chika, Russian Edition 2018 ISBN 978-5-928-72977-6

- Zvezdnyy kamen (Russian Edition), 2019 ISBN 978-5-969-11841-6

- The Commonwealth Reconstructed ISBN 978-5-871-07810-5

- Iskander, Fazil (1990). Les lapins et les boas (Littérature étrangère rivages). ISBN 978-2-869-30408-6.

- Iskander, Fazil (1988). Kroliki i udavy. p. 288. ISBN 978-5-700-00016-1.

Online

Further reading

- Russian writer of Iranian origin hailed in Moscow. Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Kriza, Elisa. "Blood Carnival and Its Variations in Mexican and Soviet Subversive Satires by René Avilés and Fazil Iskander." Comparative Literature Studies, vol. 58 no. 2, 2021, p. 397-430. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/794578.

- Milne, Lesley (1996). "Fazil' Iskander: From 'Petukh' to "Pshada"". The Slavonic and East European Review. 74 (3): 445-463. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b "There's no doubt I'm a Russian writer who praised Abkhazia a lot. Unfortunately, I haven't written anything in the Abkhaz language. The choice of Russian culture was principal to me." It is stifling to live without conscience interview in Rossiyskaya Gazeta, March 4, 2011 (in Russian)

- ^ a b c Christine Rydel. Russian Prose Writers After World War II, Volume 302. p 122. Thomson Gale, 2005 ISBN 0787668397

- ^ "A Remembrance Of Fazil Iskander: 'We Have All Lost A Close Relative'". RFERL. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ a b Haber, Erika (2003). The Myth of the Non-Russian: Iskander and Aitmatov's Magical Universe. ISBN 9780739105313. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Soviet Literature and Art: Almanac". 1990. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ "On rabbits and boa constrictors: Fazil Iskander: the 'bard of Abkhazia' who produced tragicomic chronicles of Soviet bureaucracy". NI Syndication Limited.

- ^ Edward J. Brown, Russian Literature Since the Revolution (Harvard University Press, 1982: ISBN 0-674-78204-6), p. 331.

- ^ Karen L. Ryan-Hayes, Contemporary Russian Satire: A Genre Study (Cambridge University Press, 2006: ISBN 0-521-02626-1), p. 15.

- ^ "Iranian-Russian author Iskander dies at 88". Iran Daily.

- ^ a b Jacoby, Susan. "An Abkhazian Mark Twain". The New York Times. 15 May 1983. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Haber, Erika (2003). The Myth of the Non-Russian. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0531-0.

- ^ "Fazil Iskander: A Colorful, Lyrical and Deeply Funny Writer". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ "Fazil' Iskander, "Forbidden Fruit"". Swarthmore College. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ "В Абхазии появился первый памятник литературному герою". Regnum. 4 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Abkhaz writer Fazil Iskander dies, aged 87". euronews. July 31, 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ^ "Soviet humanist writer Fazil Iskander dead at 87 - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. July 31, 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ^ Polska, Grupa Wirtualna (July 31, 2016). "Pisarz Fazil Iskander nie żyje". wiadomosci.wp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ^ "Fazil Iskander passes away". vestnikkavkaza.net. July 31, 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ^ "Literature and the acceptance of faith for Fazil Iskander and other writers"".

- ^ The Myth of the Non-Russian: Iskander and Aitmatov's Magical Universe, Erika Haber, Lexington Books, UK, 2003. (Page 65: "Iskander was awarded the USSR State Prize in November 1989")

- ^ Remaking Russia: Voices from Within, Edited by Heyward Isham, Intro by Richard Pipes, M.E. Sharp 1995. (Intro, page xviii, "USSR State Prize 1989")

- ^ "Puschkin-Preis 2005 für Boris Paramonow" (in German). Alfred Toepfer Stiftung F.V.S. 2005-05-26. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ Yeltsin, Boris (2003-12-07). Указ Президента РФ от 7.12.1993 № 2120 (in Russian). Moscow: Официальный сайт Президента Российской Федерации. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ "Winners of the 2013 Russian Federation National Awards announced". Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ "abkhaz.org".

- ^ Фазиль Искандер награжден высшим орденом Абхазии (in Russian). Kafkas Vakfi. 2002-06-20. Archived from the original on 2012-02-17. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ "Fazil Iskander". Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ "Дмитрий Медведев наградил писателя Фазиля Искандера орденом "За заслуги перед Отечеством" IV степени".

- ^ "Фазиля Искандера наградили премией "Ясная Поляна"".

- ^ "Fazil Iskander International Literary Prize"".

External links

- Fazil Iskander IMDb

- Author Biography: Fazil Iskander at ELKOST International Literary Agency

- 1929 births

- 2016 deaths

- People from Sukhumi

- Abkhazian writers

- Iranian writers

- Iranian people of Abkhazian descent

- Recipients of the USSR State Prize

- Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

- Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 2nd class

- State Prize of the Russian Federation laureates

- Pushkin Prize winners

- Russian male novelists

- Soviet novelists

- Soviet male writers

- 20th-century Russian male writers

- Soviet short story writers

- 20th-century Russian short story writers

- Honorary Members of the Russian Academy of Arts

- Russian humorists

- Russian people of Abkhazian descent

- Russian people of Iranian descent

- Russian male short story writers

- Soviet people of Iranian descent

- Maxim Gorky Literature Institute alumni