Room-temperature superconductor: Difference between revisions

→top: Separate heading for significance - see talk page Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit |

m →Reports: Reworded mention of Josephson sentence to more directly relate to LK-99. Seems like a more general statement though, and may not belong in a paragraph specific to one material |

||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

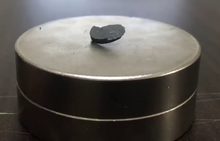

[[File:LK-99 pellet.png|thumb|Pellet of LK-99]] |

[[File:LK-99 pellet.png|thumb|Pellet of LK-99]] |

||

<!-- Best to wait until a secondary source reports this ---- IFL also reported this --> |

<!-- Best to wait until a secondary source reports this ---- IFL also reported this --> |

||

On July 23, 2023, a Korean team from the Quantum Energy Research Center and [[Korea Institute of Science and Technology|Korean Institute of Science and Technology]] (KIST) posted a paper to the [[arXiv]] preprint server entitled "The First Room-Temperature Ambient-Pressure Superconductor", describing a novel RTSC they called [[LK-99]].<ref>{{cite arXiv|title=The First Room-Temperature Ambient-Pressure Superconductor|eprint=2307.12008 |last1=Lee |first1=Sukbae |last2=Kim |first2=Ji-Hoon |last3=Kwon |first3=Young-Wan |date=2023 |class=cond-mat.supr-con }}</ref> The paper was accompanied by a sister paper on arXiv,<ref>{{cite arXiv|title=Superconductor Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O showing levitation at room temperature and atmospheric pressure and mechanism|eprint=2307.12037 |last1=Lee |first1=Sukbae |last2=Kim |first2=Jihoon |last3=Kim |first3=Hyun-Tak |last4=Im |first4=Sungyeon |last5=An |first5=SooMin |author6=Keun Ho Auh |date=2023 |class=cond-mat.supr-con }}</ref> a paper in a Korean journal,<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://journal.kci.go.kr/jkcgct/archive/articleView?artiId=ART002955269|title=다음논문 Consideration for the development of room-temperature ambient-pressure superconductor (LK-99)|journal=Journal of the Korean Crystal Growth and Crystal Technology |date=April 2023 |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=61–70 |access-date=26 July 2023|archive-date=26 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230726083507/http://journal.kci.go.kr/jkcgct/archive/articleView?artiId=ART002955269|url-status=live |last1=Lee |first1=Sukbae |last2=Kim |first2=Jihoon |last3=Im |first3=Sungyeon |last4=An |first4=Soomin |last5=Kwon |first5=Young-Wan |last6=Ho |first6=Auh Keun }}</ref> and a patent application.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2023027536A1/en?oq=WO2023027536A1|title=Room temperature and normal pressure superconducting ceramic compound, and method for manufacturing same|access-date=26 July 2023|archive-date=26 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230726001509/https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2023027536A1/en?oq=WO2023027536A1|url-status=live}}</ref> Multiple experts have expressed skepticism, with Oxford materials science professor Susannah Speller stating that "it is too early to say that we have been presented with compelling evidence for superconductivity in these samples", due to the lack of clear signatures of superconductivity, like magnetic field response and heat capacity. Other experts have expressed concerns that the data may be explained by "errors in the experimental procedure combined with imperfections in the LK-99 sample", and one scientist questioned the theoretical model used by the researchers.<ref>{{cite magazine | last=Padavic-Callaghn| first=Karmela | date=26 July 2023 |magazine=[[New Scientist]]|title=Room-temperature superconductor 'breakthrough' met with scepticism|url= https://www.newscientist.com/article/2384782-room-temperature-superconductor-breakthrough-met-with-scepticism|access-date=26 July 2023}}</ref> |

On July 23, 2023, a Korean team from the Quantum Energy Research Center and [[Korea Institute of Science and Technology|Korean Institute of Science and Technology]] (KIST) posted a paper to the [[arXiv]] preprint server entitled "The First Room-Temperature Ambient-Pressure Superconductor", describing a novel RTSC they called [[LK-99]].<ref>{{cite arXiv|title=The First Room-Temperature Ambient-Pressure Superconductor|eprint=2307.12008 |last1=Lee |first1=Sukbae |last2=Kim |first2=Ji-Hoon |last3=Kwon |first3=Young-Wan |date=2023 |class=cond-mat.supr-con }}</ref> The paper was accompanied by a sister paper on arXiv,<ref>{{cite arXiv|title=Superconductor Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O showing levitation at room temperature and atmospheric pressure and mechanism|eprint=2307.12037 |last1=Lee |first1=Sukbae |last2=Kim |first2=Jihoon |last3=Kim |first3=Hyun-Tak |last4=Im |first4=Sungyeon |last5=An |first5=SooMin |author6=Keun Ho Auh |date=2023 |class=cond-mat.supr-con }}</ref> a paper in a Korean journal,<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://journal.kci.go.kr/jkcgct/archive/articleView?artiId=ART002955269|title=다음논문 Consideration for the development of room-temperature ambient-pressure superconductor (LK-99)|journal=Journal of the Korean Crystal Growth and Crystal Technology |date=April 2023 |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=61–70 |access-date=26 July 2023|archive-date=26 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230726083507/http://journal.kci.go.kr/jkcgct/archive/articleView?artiId=ART002955269|url-status=live |last1=Lee |first1=Sukbae |last2=Kim |first2=Jihoon |last3=Im |first3=Sungyeon |last4=An |first4=Soomin |last5=Kwon |first5=Young-Wan |last6=Ho |first6=Auh Keun }}</ref> and a patent application.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2023027536A1/en?oq=WO2023027536A1|title=Room temperature and normal pressure superconducting ceramic compound, and method for manufacturing same|access-date=26 July 2023|archive-date=26 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230726001509/https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2023027536A1/en?oq=WO2023027536A1|url-status=live}}</ref> Multiple experts have expressed skepticism, with Oxford materials science professor Susannah Speller stating that "it is too early to say that we have been presented with compelling evidence for superconductivity in these samples", due to the lack of clear signatures of superconductivity, like magnetic field response and heat capacity. Other experts have expressed concerns that the data may be explained by "errors in the experimental procedure combined with imperfections in the LK-99 sample", and one scientist questioned the theoretical model used by the researchers.<ref>{{cite magazine | last=Padavic-Callaghn| first=Karmela | date=26 July 2023 |magazine=[[New Scientist]]|title=Room-temperature superconductor 'breakthrough' met with scepticism|url= https://www.newscientist.com/article/2384782-room-temperature-superconductor-breakthrough-met-with-scepticism|access-date=26 July 2023}}</ref> Testing is ongoing, and the ultimate proof that the material is a genuine superconductor will occur if it shows macroscopic quantum behavior such as the [[Josephson effect]] (DC SQUID) as was demonstrated in 1987 by De Waele et al. in the case of YBCO.<ref name="dW1987">{{Cite journal |last1=de Waele |first1=A.Th.A.M. |last2=Smokers |first2=R.T.M. |last3= van der Heijden |first3=R.W. |last4=Kadowaki |first4=K. |last5=Huang |first5=Y.K. |last6=van Sprang |first6=M. |last7=Menovsky |first7=A.A. |date=June 1987 |title= Macroscopic quantum phenomena in high-Tc superconducting material |journal= Physical Review B |volume=36 |issue=16 |pages=8858–8860}}</ref> |

||

The ultimate proof that a material is a genuine superconductor is when it shows macroscopic quantum behavior such as the [[Josephson effect]] (DC SQUID) as was demonstrated in 1987 by De Waele et al. in the case of YBCO.<ref name="dW1987">{{Cite journal |last1=de Waele |first1=A.Th.A.M. |last2=Smokers |first2=R.T.M. |last3= van der Heijden |first3=R.W. |last4=Kadowaki |first4=K. |last5=Huang |first5=Y.K. |last6=van Sprang |first6=M. |last7=Menovsky |first7=A.A. |date=June 1987 |title= Macroscopic quantum phenomena in high-Tc superconducting material |journal= Physical Review B |volume=36 |issue=16 |pages=8858–8860}}</ref> |

|||

==Theories== |

==Theories== |

||

Revision as of 17:10, 7 August 2023

A room-temperature superconductor is a material capable of displaying superconductivity at temperatures above 0 °C (273 K; 32 °F), which are commonly encountered in everyday settings. As of 2020, the highest reported temperature for superconductivity was observed in an extremely pressurized carbonaceous sulfur hydride, exhibiting a critical transition temperature of +15 °C (288.15 K; 59 ℉) at 267 GPa (2,635,000 atm; 38,715,000 psi).[1] However, on 22 September 2022, the original article documenting this discovery was withdrawn by the Nature journal's editorial board due to irregular and user-defined data analysis, raising concerns about the scientific validity of the claim.[2][3]

At standard atmospheric pressure, cuprates currently hold the temperature record, manifesting superconductivity at temperatures as high as 138 K (−135 °C).[4] Over time, researchers have consistently encountered superconductivity at temperatures previously considered unexpected or impossible, challenging the notion that achieving superconductivity at room temperature was unfeasible.[5][6] The concept of "near-room temperature" transient effects has been a subject of discussion since the early 1950s.

Significance

The discovery of a room-temperature superconductor would have enormous technological significance. It has the potential to address global energy challenges, enhance computing speed, enable innovative memory-storage devices, and create highly sensitive sensors, among a multitude of other possibilities.[6][7]

Reports

Since the discovery of high-temperature superconductors ("high" being temperatures above 77 K (−196.2 °C; −321.1 °F), the boiling point of liquid nitrogen), several materials have been reported to be room-temperature superconductors, although most of these reports have not been confirmed.[8][clarification needed]

In 2000, while extracting electrons from diamond during ion implantation work, Johan Prins claimed to have observed a phenomenon that he explained as room-temperature superconductivity within a phase formed on the surface of oxygen-doped type IIa diamonds in a 10−6 mbar vacuum.[9]

In 2003, a group of researchers published results on high-temperature superconductivity in palladium hydride (PdHx: x>1)[10] and an explanation in 2004.[11] In 2007, the same group published results suggesting a superconducting transition temperature of 260 K.[12] The superconducting critical temperature increases as the density of hydrogen inside the palladium lattice increases. This work has not been corroborated by other groups.

In 2012, an Advanced Materials article claimed superconducting behavior of graphite powder after treatment with pure water at temperatures as high as 300 K and above.[13][unreliable source?] So far, the authors have not been able to demonstrate the occurrence of a clear Meissner phase and the vanishing of the material's resistance.

In 2014, an article published in Nature suggested that some materials, notably YBCO (yttrium barium copper oxide), could be made to superconduct at room temperature using infrared laser pulses.[14]

In 2015, an article published in Nature by researchers of the Max Planck Institute suggested that under certain conditions such as extreme pressure H

2S transitioned to a superconductive form H

3S at 150 GPa (around 1.5 million times atmospheric pressure) in a diamond anvil cell.[15] The critical temperature is 203 K (−70 °C) which would be the highest Tc ever recorded and their research suggests that other hydrogen compounds could superconduct at up to 260 K (−13 °C).[16][17]

In 2018, Dev Kumar Thapa and Anshu Pandey from the Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit of the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore claimed the observation of superconductivity at ambient pressure and room temperature in films and pellets of a nanostructured material that is composed of silver particles embedded in a gold matrix.[18] Due to similar noise patterns of supposedly independent plots and the publication's lack of peer review, the results have been called into question.[19] Although the researchers validated their findings in a later paper in 2019,[20] this claim is yet to be verified and confirmed.[citation needed]

Also in 2018, researchers noted a possible superconducting phase at 260 K (−13 °C) in lanthanum decahydride (LaH

10) at elevated (200 GPa) pressure.[21] In 2019, the material with the highest accepted superconducting temperature was highly pressurized lanthanum decahydride, whose transition temperature is approximately 250 K (−23 °C).[22][23]

In October 2020, room-temperature superconductivity at 288 K (at 15 °C) was reported in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride at very high pressure (267 GPa) triggered into crystallisation via green laser.[24][25] The paper has been retracted in 2022 as doubts were raised concerning the statistical methods used by the authors to derive the result.[26]

In March 2021, an announcement reported room-temperature superconductivity in a layered yttrium-palladium-hydron material at 262 K and a pressure of 187 GPa. Palladium may act as a hydrogen migration catalyst in the material.[27]

In March 2023, superconductivity at a temperature of 294 K, and a pressure of 1 GPa, was reported in a nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride material.[28] The claim has been met with some skepticism as it was made by the same researchers (see Ranga P. Dias) that made similar claims retracted by Nature in 2022[29][30][31][32][33] and claimed observation of solid metallic hydrogen in 2016 as well as other allegations.[34] Dense group IVa hydrides (as the new material) have been previously suggested could be superconductors at lower pressures than metallic hydrogen.[35][36] First attempts to replicate the results of superconductivity in nitrogen-doped lutetium hydride have failed, although the authors of the attempt recognize improvements could be made.[37][38] Later attempts made by a different team using the original samples instead of newly prepared ones seem to confirm the reality of superconductivity in the Lu-N-H system.[39][40]

On July 23, 2023, a Korean team from the Quantum Energy Research Center and Korean Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) posted a paper to the arXiv preprint server entitled "The First Room-Temperature Ambient-Pressure Superconductor", describing a novel RTSC they called LK-99.[41] The paper was accompanied by a sister paper on arXiv,[42] a paper in a Korean journal,[43] and a patent application.[44] Multiple experts have expressed skepticism, with Oxford materials science professor Susannah Speller stating that "it is too early to say that we have been presented with compelling evidence for superconductivity in these samples", due to the lack of clear signatures of superconductivity, like magnetic field response and heat capacity. Other experts have expressed concerns that the data may be explained by "errors in the experimental procedure combined with imperfections in the LK-99 sample", and one scientist questioned the theoretical model used by the researchers.[45] Testing is ongoing, and the ultimate proof that the material is a genuine superconductor will occur if it shows macroscopic quantum behavior such as the Josephson effect (DC SQUID) as was demonstrated in 1987 by De Waele et al. in the case of YBCO.[46]

Theories

Theoretical work by British physicist Neil Ashcroft predicted that solid metallic hydrogen at extremely high pressure (~500 GPa) should become superconducting at approximately room temperature because of its extremely high speed of sound and expected strong coupling between the conduction electrons and the lattice vibrations (phonons).[47] This prediction is yet to be experimentally verified, as the pressure to achieve metallic hydrogen is unknown and may be on the order of 500 GPa.

A team at Harvard University has claimed to make metallic hydrogen and reports a pressure of 495 GPa.[48] Though the exact critical temperature has not yet been determined, weak signs of a possible Meissner effect and changes in magnetic susceptibility at 250 K may have appeared in early magnetometer tests on the original now-lost sample and is being analyzed by the French team working with doughnut shapes rather than planar at the diamond culet tips.[49]

In 1964, William A. Little proposed the possibility of high-temperature superconductivity in organic polymers.[50] This proposal is based on the exciton-mediated electron pairing, as opposed to phonon-mediated pairing in BCS theory.

In 2004, Ashcroft returned to his idea and suggested that hydrogen-rich compounds can become metallic and superconducting at lower pressures than hydrogen. More specifically, he proposed a novel way to pre-compress hydrogen chemically by examining IVa hydrides.[35]

In 2016, research suggested a link between palladium hydride containing small impurities of sulfur nanoparticles as a plausible explanation for the anomalous transient resistance drops seen during some experiments, and hydrogen absorption by cuprates was suggested in light of the 2015 results in H

2S as a plausible explanation for transient resistance drops or "USO" noticed in the 1990s by Chu et al. during research after the discovery of YBCO.[citation needed][51] It is also possible that if the bipolaron explanation is correct, a normally semiconducting material can transition under some conditions into a superconductor if a critical level of alternating spin coupling in a single plane within the lattice is exceeded; this may have been documented in very early experiments from 1986. The best analogy here would be anisotropic magnetoresistance, but in this case the outcome is a drop to zero rather than a decrease within a very narrow temperature range for the compounds tested similar to "re-entrant superconductivity".[citation needed]

In 2018, support was found for electrons having anomalous 3/2 spin states in YPtBi.[52] Though YPtBi is a relatively low temperature superconductor, this does suggest another approach to creating superconductors.

It was also discovered that many superconductors, including the cuprates and iron pnictides, have two or more competing mechanisms fighting for dominance (charge density wave)[citation needed] and excitonic states so, as with organic light emitting diodes and other quantum systems, adding the right spin catalyst may by itself increase Tc. A possible candidate would be iridium or gold placed in some of the adjacent molecules or as a thin surface layer so the correct mechanism then propagates throughout the entire lattice similar to a phase transition. As yet, this is speculative; some efforts have been made, notably adding lead to BSCCO, which is well known to help promote high Tc phases by chemistry alone. However, relativistic effects similar to those found in lead-acid batteries might be responsible suggesting that a similar mechanism in mercury- or thallium-based cuprates may be possible using a related metal such as tin.

Any such catalyst would need to be nonreactive chemically but have properties that affect one mechanism but not the others, and also not interfere with subsequent annealing and oxygenation steps nor change the lattice resonances excessively. A possible workaround for the issues discussed would be to use strong electrostatic fields to hold the molecules in place during one of the steps until the lattice is formed.[original research?]

Some research efforts are currently moving towards ternary superhydrides, where it has been predicted that Li

2MgH

16 (bilithium magnesium hexadecahydride) would have a Tc of 473 K (200 °C) at 250 GPa[53][54] (much hotter than what is normally considered room temperature).

On the side of binary superhydrides, it has been predicted that ScH

12 (scandium dodedecahydride) would exhibit superconductivity at room temperature – Tc between 333 K (60 °C) and 398 K (125 °C) – under a pressure expected not to exceed 100 GPa.[55]

References

- ^ Snider, Elliot; Dasenbrock-Gammon, Nathan; McBride, Raymond; Debessai, Mathew; Vindana, Hiranya; Vencatasamy, Kevin; Lawler, Keith V.; Salamat, Ashkan; Dias, Ranga P. (15 October 2020). "Room-temperature superconductivity in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride". Nature. 586 (7829): 373–377. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..373S. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2801-z. OSTI 1673473. PMID 33057222. S2CID 222823227.

- ^ Hand, Eric (26 September 2022). "'Something is seriously wrong': Room-temperature superconductivity study retracted". Science. 377 (6614): 1474–1475. doi:10.1126/science.adf0773. PMID 36173853. S2CID 252622995. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

After doubts grew, blockbuster Nature paper is withdrawn over objections of study team

- ^ Snider, Elliot; Dasenbrock-Gammon, Nathan; McBride, Raymond; Debessai, Mathew; Vindana, Hiranya; Vencatasamy, Kevin; Lawler, Keith V.; Salamat, Ashkan; Dias, Ranga P. (26 September 2022). "Retraction Note: Room-temperature superconductivity in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride". Nature. 610 (7933): 804. Bibcode:2022Natur.610..804S. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05294-9. PMID 36163290. S2CID 252544156.

- ^ Dai, Pengcheng; Chakoumakos, Bryan C.; Sun, G.F.; Wong, Kai Wai; Xin, Ying; Lu, D.F. (1995). "Synthesis and neutron powder diffraction study of the superconductor HgBa2Ca2Cu3O8+δ by Tl substitution". Physica C. 243 (3–4): 201–206. Bibcode:1995PhyC..243..201D. doi:10.1016/0921-4534(94)02461-8.

- ^ Geballe, Theodore Henry (12 March 1993). "Paths to Higher Temperature Superconductors". Science. 259 (5101): 1550–1551. Bibcode:1993Sci...259.1550G. doi:10.1126/science.259.5101.1550. PMID 17733017.

- ^ a b Jones, Barbara A.; Roche, Kevin P. (25 July 2016). "Almaden Institute 2012: Superconductivity 297 K – Synthetic Routes to Room Temperature Superconductivity". researcher.watson.ibm.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ NOVA. Race for the Superconductor. Public TV station WGBH Boston. Approximately 1987.

- ^ Garisto, Dan (27 July 2023). "Viral New Superconductivity Claims Leave Many Scientists Skeptical". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Prins, Johan F (1 March 2003). "The diamond vacuum interface: II. Electron extraction from n-type diamond: evidence for superconduction at room temperature". Semiconductor Science and Technology. 18 (3): S131 – S140. Bibcode:2003SeScT..18S.131P. doi:10.1088/0268-1242/18/3/319. S2CID 250881569.

- ^ Tripodi, Paolo; Di Gioacchino, Daniele; Borelli, Rodolfo; Vinko, Jenny Darja (May 2003). "Possibility of high temperature superconducting phases in PdH". Physica C: Superconductivity. 388–389: 571–572. Bibcode:2003PhyC..388..571T. doi:10.1016/S0921-4534(02)02745-4.

- ^ Tripodi, Paolo; Di Gioacchino, Daniele; Vinko, Jenny Darja (August 2004). "Superconductivity in PdH: Phenomenological explanation". Physica C: Superconductivity. 408–410: 350–352. Bibcode:2004PhyC..408..350T. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2004.02.099.

- ^ Tripodi, Paolo; Di Gioacchino, Daniele; Vinko, Jenny Darja (2007). "A review of high temperature superconducting property of PdH system". International Journal of Modern Physics B. 21 (18&19): 3343–3347. Bibcode:2007IJMPB..21.3343T. doi:10.1142/S0217979207044524.

- ^ Scheike, Thomas; Böhlmann, Winfried; Esquinazi, Pablo; Barzola-Quiquia, José; Ballestar, Ana; Setzer, Annette (2012). "Can Doping Graphite Trigger Room Temperature Superconductivity? Evidence for Granular High-Temperature Superconductivity in Water-Treated Graphite Powder". Advanced Materials. 24 (43): 5826–31. arXiv:1209.1938. Bibcode:2012AdM....24.5826S. doi:10.1002/adma.201202219. PMID 22949348. S2CID 205246535.

- ^ Mankowsky, Roman; Subedi, Alaska; Först, Michael; Mariager, Simon O.; Chollet, Matthieu; Lemke, Henrik T.; Robinson, Joseph Stephen; Glownia, James M.; Minitti, Michael P.; Frano, Alex; Fechner, Michael; Spaldin, Nicola Ann; Loew, Toshinao; Keimer, Bernhard; Georges, Antoine; Cavalleri, Andrea (2014). "Nonlinear lattice dynamics as a basis for enhanced superconductivity in YBa2Cu3O6.5". Nature. 516 (7529): 71–73. arXiv:1405.2266. Bibcode:2014Natur.516...71M. doi:10.1038/nature13875. PMID 25471882. S2CID 3127527.

- ^ Drozdov, A. P.; Eremets, M. I.; Troyan, I. A.; Ksenofontov, V.; Shylin, S. I. (2015). "Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system". Nature. 525 (7567): 73–76. arXiv:1506.08190. Bibcode:2015Natur.525...73D. doi:10.1038/nature14964. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 26280333. S2CID 4468914. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Cartlidge, Edwin (18 August 2015). "Superconductivity record sparks wave of follow-up physics". Nature. 524 (7565): 277. Bibcode:2015Natur.524..277C. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18191. PMID 26289188.

- ^ Ge, Yanfeng; Zhang, Fan; Yao, Yugui (2016). "First-principles demonstration of superconductivity at 280 K (7 °C) in hydrogen sulfide with low phosphorus substitution". Phys. Rev. B. 93 (22): 224513. arXiv:1507.08525. Bibcode:2016PhRvB..93v4513G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.93.224513. S2CID 118730557. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Thapa, Dev Kumar; Pandey, Anshu (2018). "Evidence for superconductivity at ambient temperature and pressure in nanostructures". arXiv:1807.08572 [cond-mat.supr-con].

- ^ Desikan, Shubashree (18 August 2018). "IISc duo's claim of ambient superconductivity may have support in theory". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Prasad, R.; Desikan, Shubashree (25 May 2019). "Finally, IISc team confirms breakthrough in superconductivity at room temperature". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ Grant, Andrew (23 August 2018). "Pressurized superconductors approach room-temperature realm". Physics Today. doi:10.1063/PT.6.1.20180823b. S2CID 240297717.

- ^ Somayazulu, Maddury; Ahart, Muhtar; Mishra, Ajay Kumar; Geballe, Zachary M.; Baldini, Maria; Meng, Yue; Struzhkin, Viktor V.; Hemley, Russell Julian (2019). "Evidence for Superconductivity above 260K in Lanthanum Superhydride at Megabar Pressures". Phys. Rev. Lett. 122 (2): 027001. arXiv:1808.07695. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.122b7001S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.027001. PMID 30720326. S2CID 53622077.

- ^ Drozdov, Alexander P.; Kong, Panpan; Minkov, Vasily S.; Besedin, Stanislav P.; Kuzovnikov, Mikhail A.; Mozaffari, Shirin; Balicas, Luis; Balakirev, Fedor F.; Graf, David E.; Prakapenka, Vitali B.; Greenberg, Eran; Knyazev, Dmitry A.; Tkacz, Marek; Eremets, Mikhail Ivanovich (2019). "Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures". Nature. 569 (7757): 528–531. arXiv:1812.01561. Bibcode:2019Natur.569..528D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1201-8. PMID 31118520. S2CID 119231000.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (14 October 2020). "Finally, the First Room-Temperature Superconductor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Snider, Elliot; Dasenbrock-Gammon, Nathan; McBride, Raymond; Debessai, Mathew; Vindana, Hiranya; Vencatasamy, Kevin; Lawler, Keith V.; Salamat, Ashkan; Dias, Ranga P. (October 2020). "Room-temperature superconductivity in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride". Nature. 586 (7829): 373–377. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..373S. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2801-z. OSTI 1673473. PMID 33057222. S2CID 222823227.

- ^ Hand, Eric (26 September 2022). "'Something is Seriously Wrong':Room-Temperature superconductivity study retracted". Science. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "A material that is superconductive at room temperature and lower pressure". Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Kenneth Chang (8 March 2023). "New Room-Temperature Superconductor Offers Tantalizing Possibilities". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ Dasenbrock-Gammon, Nathan; Snider, Elliot; McBride, Raymond; Pasan, Hiranya; Durkee, Dylan; Khalvashi-Sutter, Nugzari; Munasinghe, Sasanka; Dissanayake, Sachith E.; Lawler, Keith V.; Salamat, Ashkan; Dias, Ranga P. (9 March 2023). "Evidence of near-ambient superconductivity in a N-doped lutetium hydride". Nature. 615 (7951): 244–250. Bibcode:2023Natur.615..244D. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05742-0. PMID 36890373. S2CID 257407449. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023 – via www.nature.com.

- ^ Woodward, Aylin (8 March 2023). "The Scientific Breakthrough That Could Make Batteries Last Longer". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "'Revolutionary' blue crystal resurrects hope of room temperature superconductivity". www.science.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Margo Anderson (8 March 2023). "Room-Temperature Superconductivity Claimed". IEEE Spectrum. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ Wood, Charlie; Savitsky, Zack (8 March 2023). "Room-Temperature Superconductor Discovery Meets With Resistance". Quanta Magazine. Simons Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Garisto, Dan (9 March 2023). "Allegations of Scientific Misconduct Mount as Physicist Makes His Biggest Claim Yet". Physics. 16: 40. Bibcode:2023PhyOJ..16...40G. doi:10.1103/Physics.16.40. S2CID 257615348. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ a b Ashcroft, N. W. (2004). "Hydrogen Dominant Metallic Alloys: High Temperature superconductors". Physical Review Letters. 92 (18): 1748–1749. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92r7002A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.187002. PMID 15169525.

- ^ Ming, Xue; Zhang, Ying-Jie; Zhu, Xiyu; Li, Qing; He, Chengping; Liu, Yuecong; Huang, Tianheng; Liu, Gan; Zheng, Bo; Yang, Huan; Sun, Jian; Xi, Xiaoxiang; Wen, Hai-Hu (11 May 2023). "Absence of near-ambient superconductivity in LuH2±xNy". Nature. 620 (7972): 72–77. arXiv:2303.08759. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06162-w. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 10396964. PMID 37168015. S2CID 257532922.

- ^ Yirka, Bob (17 May 2023). "Replication of room-temperature superconductor claims fails to show superconductivity". Archived from the original on 18 June 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Wilkins, Alex (17 March 2023). "'Red matter' superconductor may not be a wonder material after all". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (24 June 2023). "New Study Bolsters Room-Temperature Superconductor Claim". New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Salke, Nilesh P.; Mark, Alexander C.; Ahart, Muhtar; Hemley, Russell J. (9 June 2023). "Evidence for Near Ambient Superconductivity in the Lu-N-H System". arXiv:2306.06301 [cond-mat].

- ^ Lee, Sukbae; Kim, Ji-Hoon; Kwon, Young-Wan (2023). "The First Room-Temperature Ambient-Pressure Superconductor". arXiv:2307.12008 [cond-mat.supr-con].

- ^ Lee, Sukbae; Kim, Jihoon; Kim, Hyun-Tak; Im, Sungyeon; An, SooMin; Keun Ho Auh (2023). "Superconductor Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O showing levitation at room temperature and atmospheric pressure and mechanism". arXiv:2307.12037 [cond-mat.supr-con].

- ^ Lee, Sukbae; Kim, Jihoon; Im, Sungyeon; An, Soomin; Kwon, Young-Wan; Ho, Auh Keun (April 2023). "다음논문 Consideration for the development of room-temperature ambient-pressure superconductor (LK-99)". Journal of the Korean Crystal Growth and Crystal Technology. 33 (2): 61–70. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Room temperature and normal pressure superconducting ceramic compound, and method for manufacturing same". Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Padavic-Callaghn, Karmela (26 July 2023). "Room-temperature superconductor 'breakthrough' met with scepticism". New Scientist. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ de Waele, A.Th.A.M.; Smokers, R.T.M.; van der Heijden, R.W.; Kadowaki, K.; Huang, Y.K.; van Sprang, M.; Menovsky, A.A. (June 1987). "Macroscopic quantum phenomena in high-Tc superconducting material". Physical Review B. 36 (16): 8858–8860.

- ^ Ashcroft, N. W. (1968). "Metallic Hydrogen: A High-Temperature Superconductor?". Physical Review Letters. 21 (26): 1748–1749. Bibcode:1968PhRvL..21.1748A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.21.1748.

- ^ Johnston, Ian (26 January 2017). "Hydrogen turned into metal in stunning act of alchemy that could revolutionise technology and spaceflight". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Loubeyre, Paul; Occelli, Florent; Dumas, Paul (2019). "Observation of a first order phase transition to metal hydrogen near 425 GPa". arXiv:1906.05634 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci].

- ^ Little, W. A. (1964). "Possibility of Synthesizing an Organic Superconductor". Physical Review. 134 (6A): A1416 – A1424. Bibcode:1964PhRv..134.1416L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.134.A1416.

- ^ Transient High-Temperature Superconductivity in Palladium Hydride. Griffith University (Griffith thesis). Griffith University. 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ MacDonald, Fiona (9 April 2018). "Physicists Just Discovered an Entirely New Type of Superconductivity". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Sun, Ying; Lv, Jian; Xie, Yu; Liu, Hanyu; Ma, Yanming (26 August 2019). "Route to a Superconducting Phase above Room Temperature in Electron-Doped Hydride Compounds under High Pressure". Physical Review Letters. 123 (9): 097001. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.123i7001S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.097001. PMID 31524448. S2CID 202123043. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

The recent theory-orientated discovery of record high-temperature superconductivity (Tc~250 K) in sodalitelike clathrate LaH10 is an important advance toward room-temperature superconductors. Here, we identify an alternative clathrate structure in ternary Li

2MgH

16 with a remarkably high estimated Tc of ~473 K at 250 GPa, which may allow us to obtain room-temperature or even higher-temperature superconductivity. - ^ Extance, Andy (1 November 2019). "The race is on to make the first room temperature superconductor". www.chemistryworld.com. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

In August, Ma and colleagues published a study that showed the promise of ternary superhydrides. They predicted that Li

2MgH

16 would have a Tc of 473 K at 250 GPa, far in excess of room temperature. - ^ Jiang, Qiwen; Duan, Defang; Song, Hao; Zhang, Zihan; Huo, Zihao; Cui, Tian; Yao, Yansun (6 February 2023). "Room temperature superconductivity in ScH12 with quasi-atomic hydrogen below megabar pressure". arXiv:2302.02621 [cond-mat.supr-con].