Mary Dyer: Difference between revisions

Hairy Dude (talk | contribs) →Memorials and honors: copy edit Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

Hairy Dude (talk | contribs) →Children and descendants: don't use explicit image sizes; links Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 213: | Line 213: | ||

== Children and descendants == |

== Children and descendants == |

||

[[File:RI Governor Elisha Dyer.jpg|thumb| |

[[File:RI Governor Elisha Dyer.jpg|thumb|upright=0.7|right|Rhode Island Governor [[Elisha Dyer]] descends from Mary Dyer]] |

||

Mary Dyer had eight known children, six of whom grew to adulthood. |

Mary Dyer had eight known children, six of whom grew to adulthood. Following her martyrdom, her husband remarried and had one more known child, and possibly others. Her oldest child, William, was baptized at [[St Martin-in-the-Fields]], London, on 24 October 1634 and was buried there three days later. After sailing to New England, her second child, Samuel, was baptized at the Boston church on 20 December 1635 and married by 1663 to Anne Hutchinson, the daughter of [[Edward Hutchinson (captain)|Edward Hutchinson]] and the granddaughter of William and Anne Hutchinson. Her third child was the premature stillborn female, born 17 October 1637, discussed earlier. Henry, born roughly 1640, was the fourth child, and he married Elizabeth Sanford, the daughter of John Sanford, Jr., and the granddaughter of Governor [[John Sanford (governor)|John Sanford]].{{Sfn|Anderson|Sanborn|Sanborn|2001|pp=382–383}} |

||

The fifth child was a second William, born about 1642, who married Mary, possibly a daughter of Richard Walker of Lynn, Massachusetts, but no evidence supports this. |

The fifth child was a second William, born about 1642, who married Mary, possibly a daughter of Richard Walker of Lynn, Massachusetts, but no evidence supports this. Child number six was a male and given the Biblical name [[Maher-shalal-hash-baz|Mahershallalhashbaz]]. He was married to Martha Pearce, the daughter of Richard Pearce. Mary was the seventh child, born roughly 1647, and married by about 1675 Henry Ward; they were living in Cecil County, Maryland, in January 1679. Mary Dyer's youngest child was Charles, born roughly 1650, whose first wife was named Mary; there are unsupported claims that she was a daughter of John Lippett. Charles married second after 1690 Martha (Brownell) Wait, who survived him.{{Sfn|Anderson|Sanborn|Sanborn|2001|pp=382–383}} |

||

There is no evidence that Mary's husband, William Dyer, ever became a Quaker. There was a lot of litigation concerning the estate of William Dyer, Sr; his widow, Katherine, took both the widow of his son Samuel and later his son Charles to court over the estate, likely feeling that more of his estate belonged to his children with her.{{Sfn|Anderson|Sanborn|Sanborn|2001|pp=384–385}} |

There is no evidence that Mary's husband, William Dyer, ever became a Quaker. There was a lot of litigation concerning the estate of William Dyer, Sr; his widow, Katherine, took both the widow of his son Samuel and later his son Charles to court over the estate, likely feeling that more of his estate belonged to his children with her.{{Sfn|Anderson|Sanborn|Sanborn|2001|pp=384–385}} |

||

Revision as of 19:43, 2 September 2023

Mary Dyer | |

|---|---|

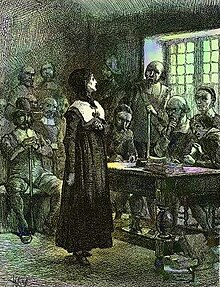

Dyer being led to the gallows in Boston in 1660, painted c. 1905 by Howard Pyle | |

| Born | Mary Dyer c. 1611 England |

| Died | 1 June 1660 (aged 48–49) |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse(s) | William Dyer (Dier, Dyre) |

| Religion | Puritan, Quaker |

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan-turned-Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony. She is one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs.

Dyer's birthplace has not been established, but it is known that she was married in London in 1633 to William Dyer, a member of the Fishmongers' Company but a milliner by profession. Mary and William were Puritans who were interested in reforming the Anglican Church from within, without separating from it. As the King of England, Charles I increased pressure on the Puritans; they left England by the thousands to go to New England in the early 1630s. Mary and William arrived in Boston by 1635, joining the Boston Church in December of that year. Like most members of Boston's church, they soon became involved in the Antinomian Controversy, a theological crisis lasting from 1636 to 1638. Mary and William were strong advocates of Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright in the controversy, and as a result, Mary's husband was disenfranchised and disarmed for supporting these "heretics" and also for harboring his own heretical views. Subsequently, they left Massachusetts with many others to establish a new colony on Aquidneck Island (later Rhode Island) in Narraganset Bay.

Before leaving Boston, Mary had given birth to a severely deformed infant that was stillborn. Because of the religious superstitions of the time regarding such a birth, the baby was buried secretly. When the Massachusetts authorities learned of this birth, the ordeal became public, and in the minds of the colony's ministers and magistrates, the monstrous birth was clearly a result of Mary's "monstrous" religious opinions. More than a decade later, in late 1651, Mary Dyer boarded a ship for England, and stayed there for over five years, during which time she converted to Quakerism. Because Quakers were considered among the most dangerous of heretics by the Puritans, Massachusetts enacted several laws against them. When Dyer returned to Boston from England, she was immediately imprisoned and then banished. Defying her order of banishment, she was again banished, this time upon pain of death. Deciding that she would die as a martyr if the anti-Quaker laws were not repealed, Dyer once again returned to Boston and was sent to the gallows in 1659, having the rope around her neck when a reprieve was announced. She returned once more to Boston the following year and was then hanged—the third of four Quaker martyrs.

Early life

Details of the life of Mary Dyer in England are scarce; only her marriage record and a short probate record for her brother have been found. In both of these English records, her name is given as Marie Barret. A belief that Dyer was the daughter of Lady Arbella Stuart and Sir William Seymour was debunked by genealogist G. Andrews Moriarty in 1950. However, Moriarty correctly predicted that despite his work the legend would persist, and in 1994 the tradition was included as being plausible in a published biography of Dyer.[1][2]

While the parents of Mary Dyer have not been identified, Johan Winsser made a significant discovery concerning a brother of Dyer, which he published in 2004. On 18 January 1634 [O.S. 1633],[3] a probate administration was recorded in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury for a William Barret. The instrument granted administration of Barret's estate "jointly to William Dyer of St Martin-in-the-Fields, fishmonger, and his wife Marie Dyer, otherwise Barret."[1] The fact that the estate of a brother of Mary Dyer would be left in the hands of Mary and her husband strongly suggests that William (and therefore Mary) had no living parents and no living brothers at the time, and also suggests that Mary was either William Barrett's only living sister, or his oldest living sister. The other facts that could be drawn from the instrument are that William Barrett was unmarried and that he died somewhere "beyond the seas" from England.[1]

That Mary was well educated is apparent from the two surviving letters that she wrote.[4] Quaker chronicler George Bishop described her as a "Comely Grave Woman, and of a goodly Personage ... and one of a good Report, having a husband of an Estate, fearing the Lord, and a Mother of Children."[5] The Dutch writer Gerard Croese wrote that she was reputed to be a "person of no mean extract and parentage, of an estate pretty plentiful, of a comely stature and countenance, of a piercing knowledge in many things, of a wonderful sweet and pleasant discourse, so fit for great affairs".[4] Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop described her as being "a very proper and fair woman ... of a very proud spirit, and much addicted to revelations".[6]

Mary was married to William Dyer, a fishmonger and milliner, on 27 October 1633 at the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, in Westminster, Middlesex, now a part of Central London.[7] Mary's husband was baptized in Lincolnshire, England.[7] Settlers from Lincolnshire contributed a disproportionately large percentage of members of the Boston Church in New England, and a disproportionately large part of the leadership during the founding of Rhode Island.[8]

Mary and William Dyer were Puritans, as evidenced by their acceptance into the membership of the Boston church in New England. The Puritans wanted to purify the Church of England from what they considered to be vestiges of Roman Catholicism that were retained after the English Reformation. The conformists in England accepted the Elizabethan via media and English monarch as the titular supreme governor of the state church. The Puritans, as non-conformists, wanted to observe a much simpler form of worship. Some of the non-conformists, such as the Pilgrims, wanted to separate completely from the Church of England. Most Puritans wished to reform the church from within. As exploration of the North American continent was then leading to settlement, many Puritans opted to avoid state sanctions by emigrating to New England to practice their form of religion.[9]

Massachusetts

In 1635, Mary and William Dyer sailed from England to New England. Mary was likely pregnant or gave birth during the voyage because on 20 December 1635 their son Samuel was baptized at the Boston church, exactly one week after the Dyers joined the church.[7][10] William Dyer became a freeman of Boston on 3 March the following year.[11]

Antinomian Controversy

During the earliest days of the Boston Church, before the arrival of Mary and William Dyer, there was a single minister, the Reverend John Wilson. In 1633, one of England's most noted Puritan clergymen, John Cotton, arrived in Boston and quickly became the second minister (called "teacher") in Boston's church. In time, the Boston parishioners could sense a theological difference between Wilson and Cotton.[12] Anne Hutchinson, a theologically astute midwife who had the ear of many of the colony's women, became outspoken in support of Cotton, and condemned the theology of Wilson and most of the other ministers in the colony during gatherings, or conventicles, held at her house.[13][14]

Differing religious opinions within the colony eventually became public debates and erupted into what has traditionally been called the Antinomian Controversy.[12] Many members of Boston's church found Wilson's emphasis on morality, and his doctrine of "evidencing justification by sanctification" (a covenant of works) to be disagreeable. Hutchinson told her followers that Wilson lacked "the seal of the Spirit".[15] Wilson's theological views conformed with those of all of the other ministers in the colony except for Cotton, who instead stressed "the inevitability of God's will" (a covenant of grace).[16] The Boston parishioners had become accustomed to Cotton's doctrines, and some of them began disrupting Wilson's sermons, even finding excuses to leave when Wilson got up to preach or pray.[17]

Both William and Mary Dyer sided strongly with Hutchinson and the free-grace advocates, and it is highly likely that Mary attended the periodic theological gatherings at the Hutchinson's home.[8] In May 1636, the Bostonians received a new ally when the Reverend John Wheelwright arrived from England, and immediately aligned himself with Cotton, Hutchinson and the other free-grace supporters.[18] Yet another boost for those advocating the free-grace theology came during the same month, when the young aristocrat Henry Vane was elected as the governor of the colony. Vane was a strong supporter of Hutchinson, but also had his own unorthodox ideas about theology that were considered radical.[12]

By late 1636, the theological schism had become great enough that the General Court called for a day of fasting to help ease the colony's difficulties. The appointed fasting day, in January, included church services, and Cotton preached during the morning, but with Wilson away in England, John Wheelwright was invited to preach during the afternoon.[19] Though his sermon may have seemed benign to the average listener in the congregation, most of the colony's ministers found Wheelwright's words to be objectionable. Instead of bringing peace, the sermon fanned the flames of controversy, and in Winthrop's words, Wheelwright "inveighed against all that walked in a covenant of works, ... and called them antichrists, and stirred up the people against them with much bitterness and vehemency."[19] In contrast, the followers of Hutchinson were encouraged by the sermon, and intensified their crusade against the "legalists" among the clergy. During church services and lectures, they publicly questioned the ministers about their doctrines which disagreed with their own beliefs.[19]

When the General Court next met on 9 March, Wheelwright was called upon to answer for his sermon.[20] He was judged guilty of "contempt & sedition" for having "purposely set himself to kindle and increase" bitterness within the colony.[20] The vote did not pass without a fight, however, and Wheelwright's friends protested formally. Most members of the Boston church, favoring Wheelwright in the conflict, drafted a petition justifying Wheelwright's sermon, and 60 people signed this remonstrance protesting the conviction.[21] William Dyer was among those who signed the petition which accused the General Court of condemning the truth of Christ. Dyer's signature in support of Wheelwright soon proved to be fateful to the Dyer family.[22]

Anne Hutchinson faced trial in early November 1637 for "traducing" (slandering) the ministers, and was sentenced to banishment on her second day in court. Within a week of her sentencing, many supporters of hers, including William Dyer, were called into court and were disenfranchised.[22] Fearing an armed insurrection, the constables were then sent from door to door throughout the colony's towns to disarm those who signed the Wheelwright petition.[23] Within ten days these individuals were ordered to deliver "all such guns, pistols, swords, powder, shot, & match as they shall be owners of, or have in their custody, upon paine of ten pound[s] for every default".[23] A great number of those who signed the petition, faced with losing their protection and in some cases livelihood, recanted under the pressure, and "acknowledged their error" in signing the petition. Those who refused to recant suffered hardships and many decided to leave the colony.[24] Being both disenfranchised and disarmed, William Dyer was among those who could no longer justify remaining in Massachusetts.[25]

"Monstrous birth"

While William Dyer appeared in the Boston records on several occasions, Mary Dyer had not caught the attention of the Massachusetts authorities until March 1638 as the Antinomian controversy came to an end. Following Hutchinson's civil trial, she was kept as a prisoner in the home of a brother of one of the colony's ministers. Though she had been banished from the colony, this did not mean she was removed as a member of the Boston church. In March 1638 she was forced to face a church trial to get at the root of her heresies, and determine if her relationship with the Puritan church would continue. While William Dyer was likely with other men finding a new home away from Massachusetts, Mary Dyer was still in Boston and in attendance at this church trial. At the conclusion of the trial, Hutchinson was excommunicated, and as she was leaving the Boston Church, Mary stood and walked hand in hand with her out of the building.[26] As the two women were leaving the church, a member of the congregation asked another person about the identity of the woman leaving the church with Hutchinson. A reply was made that it was the woman who had had the "monstrous birth". Governor Winthrop soon became aware of this verbal exchange and began conducting an investigation.[22]

Dyer had given birth five months earlier, on 11 October 1637, to a stillborn baby with dysmorphic features. Winthrop wrote that while many women had gathered for the occasion, that "none were left at the time of the birth but the midwife and two others, whereof one fell asleep".[27] Actually, two women present were midwives—Anne Hutchinson and Jane Hawkins, but the third woman was never identified. Hutchinson fully understood the serious theological implications of such a birth, and immediately sought the counsel of the Reverend John Cotton. Thinking about how he would react if this were his child, Cotton instructed Hutchinson to conceal the circumstances of the birth. The infant was then buried secretly.[28]

Once Winthrop had learned of the so-called "monstrous birth", he confronted Jane Hawkins, and armed with new information then confronted Cotton. As the news spread among the colony's leaders, it was determined that the infant would be exhumed and examined. According to Winthrop, a group of "above a hundred persons" including Winthrop, Cotton, Wilson, and the Reverend Thomas Weld "went to the place of buryall & commanded to digg it up to [behold] it, & they sawe it, a most hideous creature, a woman, a fish, a bird, & a beast all woven together".[27][29] In his journal, Winthrop provided a more complete description as follows:

it was of ordinary bigness; it had a face, but no head, and the ears stood upon the shoulders and were like an ape's; it had no forehead, but over the eyes four horns, hard and sharp; two of them were above one inch long, the other two shorter; the eyes standing out, and the mouth also; the nose hooked upward; all over the breast and back full of sharp pricks and scales, like a thornback [i.e., a skate or ray], the navel and all the belly, with the distinction of the sex, were where the back should be, and the back and hips before, where the belly should have been; behind, between the shoulders, it had two mouths, and in each of them a piece of red flesh sticking out; it had arms and legs as other children; but, instead of toes, it had on each foot three claws, like a young fowl, with sharp talons.[30]

While some of the descriptions may have been accurate, many puritanical embellishments were added to better fit the moral story being portrayed by the authorities. The modern medical condition that best fits the description of the infant is anencephaly, meaning partial or complete absence of a brain.[27] This episode was just the beginning of the attention emanating from Dyer's personal tragedy. The religion of the Puritans demanded a close look at all aspects of one's life for signs of God's approval or disapproval. Even becoming a member of the Puritan church in New England required a public confession of faith, and any behavior that was viewed by the clergy as being unorthodox required a theological examination by the church, followed by a public confession and repentance by the offender.[31] Such microscopic inspection caused even private matters to become looked at publicly for the purpose of instruction, and Dyer's tragedy was widely examined for signs of God's judgment. This led to a highly subjective form of justice, an example of which was the 1656 hanging of Ann Hibbins whose offense was simply being resented by her neighbor. In Winthrop's eyes, Dyer's case was unequivocal, and he was convinced that her "monstrous birth" was a clear signal of God's displeasure with the antinomian heretics. Winthrop felt that it was quite providential that the discovery of the "monstrous birth" occurred exactly when Anne Hutchinson was excommunicated from the local body of believers, and exactly one week before Dyer's husband was questioned in the Boston church for his heretic opinions.[32]

To further fuel Winthrop's beliefs, Anne Hutchinson suffered from a miscarriage later in the same year when she aborted a strange mass of tissue that appeared like a handful of transparent grapes (a rare condition, mostly in woman over 45, called a hydatidiform mole).[33] Winthrop was convinced of divine influence in these events, and made sure that every leader in New England received his own account of the "monster" birth, and he even sent a deposition to England. Soon, the story took on a life of its own, and in 1642 it was printed in London under the title Newes from New-England of a Most Strange and Prodigious Birth, brought to Boston in New-England. Though the author of this work was not named, it may have been the New England minister Thomas Weld who was in England at the time to support New England's ecclesiastical independence. In 1644 Weld, who was still in England, took Winthrop's account of the Antinomian Controversy, and published it under one title, and then added a preface of his own and republished it under the title A Short story of the Rise, reign and ruine of the Antinomians, Familists & Libertines, usually just called Short Story.[34] In 1648 Samuel Rutherford, a Scottish Presbyterian, included Winthrop's account of the monster in his anti-sectarian treatise A Survey of the Spirituall Antichrist, Opening the Secrets of Familisme and Antinomianisme. Even the English writer, Samuel Danforth, included the birth in his 1648 Almanack as a "memorable occurrence" from 1637. [35] The only minister who wrote without sensationalism about Dyer's deformed infant was the Reverend John Wheelwright, Anne Hutchinson's ally during the Antinomian Controversy. In his 1645 response to Winthrop's Short Story, entitled Mercurius Americanus, he wrote that Dyer's and Hutchinson's monsters described by Winthrop were nothing but "a monstrous conception of his [Winthrop's] brain, a spurious issue of his intellect".[36]

Twenty years after the tragic birth, when Mary Dyer returned to the public spotlight for her Quaker evangelism, she continued to be remembered for the birth of her dysmorphic child, this time in the diary of John Hull. Also, in 1660, an exchange of letters took place between England and New England when the two eminent English clergymen, Richard Baxter and Thomas Brooks, sought information about the "monstrous birth" from 1637. A New Englander, whose identity was not included, sent back information about the event to the English divines. The New Englander, who used Winthrop's original description of the "monster" almost verbatim, has subsequently been identified as yet another well-known clergyman, John Eliot who preached at the church in Roxbury, not far from Boston.[37]

The most outrageous accounting of Dyer's infant occurred in 1667 when a memorandum of the Englishman Sir Joseph Williamson quoted a Major Scott about the event. Scott was a country lawyer with a notorious reputation, and his detractors included the famous diarist Samuel Pepys.[38] Scott's outlandish assertion was that the young Massachusetts governor, Henry Vane, fathered the "monstrous births" of both Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson; that he "debauched both, and both were delivered of monsters".[36] After this, the accounts became less frequent, and the last historical account of Dyer's "monstrous birth" was in 1702 when the New England minister Cotton Mather mentioned it in passing in his Magnalia Christi Americana.[38]

Rhode Island

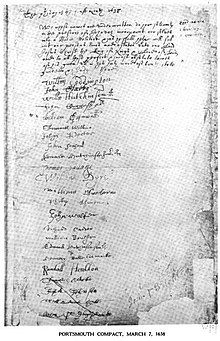

Several of those affected by the events of the Antinomian controversy went north with John Wheelwright in November 1637 to found the town of Exeter in what would become New Hampshire. A larger group, uncertain where to go, contacted Roger Williams, who suggested they purchase land from the natives along the Narraganset Bay, near his settlement in Providence. On 7 March 1638,[ambiguous] just as Anne Hutchinson's church trial was getting underway, a group of men gathered at the home of William Coddington and drafted a compact for a new government. This group included several of the strongest supporters of Hutchinson who had either been disenfranchised, disarmed, excommunicated, or banished, including William Dyer.[39] Altogether, 23 individuals signed the instrument which was intended to form a "Bodie Politick" based on Christian principles, and Coddington was chosen as the leader of the group. Following through with Roger Williams' proposed land purchase, these exiles established their colony on Aquidneck Island (later named Rhode Island), naming the settlement Pocasset.[40]

William and Mary Dyer joined William and Anne Hutchinson and many others in building the new settlement on Aquidneck Island. Within a year of the founding of this settlement, however, there was dissension among the leaders, and the Dyers joined Coddington, with several other inhabitants, in moving to the south end of the island, establishing the town of Newport. The Hutchinsons remained in Pocasset, whose inhabitants renamed the town Portsmouth, and William Hutchinson became its chief magistrate. William Dyer immediately became the recording secretary of Newport,[41] and he and three others were tasked in June 1639 to proportion the new lands.[10] In 1640 the two towns of Portsmouth and Newport united, and Coddington was elected governor, while Dyer was chosen as Secretary, and held this position from 1640 to 1647.[41] Roger Williams, who envisioned a union of all four settlements on the Narragansett Bay (Providence, Warwick, Portsmouth, and Newport), wanted royal recognition of these settlements for their protection, and went to England where he obtained a patent bringing the four towns under one government. Coddington was opposed to the Williams patent and managed to resist union with Providence and Warwick until 1647 when representatives of the four towns ultimately met and united under the patent.[42] With all four of the Narragansett settlements now under one government, William Dyer was elected the General Recorder for the entire colony in 1648.[10]

Coddington continued to be unhappy with the consolidated government, and wanted colonial independence for the two island towns. He sailed to England to present his case, and in April 1651, the Council of State of England gave him the commission he sought, making him governor-for-life of the island.[43] Criticism of Coddington arose as soon as he returned with his commission. Three men were then directed to go to England to get Coddington's commission revoked: Roger Williams, representing the mainland towns, and John Clarke and William Dyer representing the two island towns. In November 1651 the three men left for England, where Dyer would meet his wife.[44] Mary Dyer had sailed to England before the three men departed, as Coddington wrote in a letter to Winthrop that Mr. Dyer "sent his wife over in the first ship with Mr. Travice, and is now gone himself for England".[45] It remains a mystery as to why Mary Dyer would leave six children behind, one an infant, to travel abroad. Biographer Ruth Plimpton hinted that Mary had some royal connection, and suggested that the news of the execution of King Charles I compelled her to go. However, no record has been found to satisfactorily explain this mystery.[46]

Because of recent hostilities between the English and the Dutch, the three men, once in England, did not meet with the Council of State on New England until April 1652. After the men explained their case, Coddington's commission for the island government was revoked in October 1652.[44] William Dyer was the messenger who returned to Rhode Island the following February, bringing the news of the return of the colony to the Williams Patent of 1643. Mary, however, would remain in England for the next four years.[47]

Quaker conversion

England

Mary Dyer's time in England lasted for over five years, and during her stay she had become deeply interested in Quakerism. Formally known as the Society of Friends, the Quakers do not practise water baptism or the Lord's Supper, nor do they believe in an ordained ministry. Both women and men can preach and exercise spiritual authority.[48] In addition to denouncing the clergy, and refusing to support the established church by paying tithes, Quakers emphasize liberty of conscience and demand the separation of church and state. Their worship is based in silence, with spontaneous Spirit-inspired preaching or prayer by any participant. They reject various customs that emphasised class distinctions (such as men bowing or doffing their hats to social superiors); they do not take oaths, and they do not fight in wars. The Puritans in Massachusetts viewed Quakers as being among the most reprehensible of heretics, and they enacted several laws against them.[49]

It is commonly asserted that while in England, Dyer became a Quaker and received a gift in the ministry. Details are provided by Plimpton, but these are fabrications completely without documentation. Altogether, no contemporary record has been found that addresses Dyer's time in England. Moreover, when Dyer and Anne Burden arrived in Barbados on their return to New England, the Quaker Missionary Henry Fell described Dyer to Margaret Fell, while not doing the same for Burden, whose Quaker ministry in England is documented.[50] Margaret Fell was the administrative heart of early Quakerism, raising funds for missionary efforts and receiving and forwarding voluminous correspondence. That Fell had to describe Dyer to the woman who knew the most about Quaker missions and ministry suggests that Dyer was not well known among Quakers prior to leaving England. It is likely that Dyer came to her Quaker beliefs only late in her stay in England and that she did not exercise her ministry until her return to New England.

Quakers in Massachusetts

Of all the New England colonies, Massachusetts was the most active in persecuting the Quakers, but the Plymouth, Connecticut and New Haven colonies also shared in their persecution. When the first Quakers arrived in Boston in 1656 there were no laws yet enacted against them, but this quickly changed, and punishments were meted out with or without the law. It was primarily the ministers and the magistrates who opposed the Quakers and their evangelistic efforts.[51] A particularly vehement persecutor, the Reverend John Norton of the Boston church, clamored for the law of banishment upon pain of death. He is the one who later wrote the vindication to England, justifying the execution of the first two Quakers in 1659.[52]

The punishments doled out to the Quakers intensified as their perceived threat to the Puritan religious order increased. These included the stocks and pillory, lashes with a three-corded, knotted whip, fines, imprisonment, mutilation (having ears cut off), banishment and death. When whipped, women were stripped to the waist, thus being publicly exposed, and whipped until bleeding. Such was the fate of Dyer's Newport neighbor, Herodias Gardiner who had made a perilous journey through a 60-mile wilderness to get to Weymouth in the Massachusetts colony. She had made the arduous trek with another woman and with her "Babe sucking at her Breast" to give her Quaker testimony to friends in Weymouth. Similarly, Katherine Marbury Scott, the wife of Richard Scott, and a younger sister of Anne Hutchinson, had received ten lashes for petitioning for the release of future son-in-law, Christopher Holder, who was imprisoned. This was the setting into which Mary Dyer stepped, upon her return from England.[53]

Dyer's return to New England

In early 1657 Dyer returned to New England with the widow Ann Burden, who came to Boston to settle the estate of her late husband.[47][54] Dyer was immediately recognized as a Quaker and imprisoned. Dyer's husband had to come to Boston to get her out of jail, and he was bound and sworn not to allow her to lodge in any Massachusetts town, or to speak to any person while traversing the colony to return home. Dyer nevertheless continued to travel in New England to preach her Quaker message, and in early 1658 was arrested in the New Haven Colony, and then expelled for preaching her "inner light" belief, and the notion that women and men stood on equal ground in church worship and organization.[55] In addition to sharing her Quaker message, she had come to New Haven with two others to visit Humphrey Norton who had been imprisoned for three weeks. Anti-Quaker laws had been enacted there, and after Dyer was arrested, she was "set on a horse", and forced to leave.[56]

In June 1658 two Quaker activists, Christopher Holder and John Copeland came to Boston. They had already been evicted from other parts of the colony, and were exasperating the magistrates. Being joined by John Rous from Barbadoes, the three men were sentenced to having their right ears cut off, and the sentence was carried out in July.[57] As biographer Plimpton wrote, the men "were so stalwart while their ears were removed" that additional punishments in the form of whippings were carried out for the next nine weeks.[58] Word of this cruelty reached Dyer while she was visiting Richard and Katherine Scott in Providence. Richard and Katherine Scott were considered to be the first Quakers in Providence. The Scotts had two daughters, Mary, the older, who was engaged to Christopher Holder, and Patience, the younger, aged 11. Mrs. Scott and her two daughters, along with Mary Dyer and her friend Hope Clifton, were all compelled to go to Boston to visit with Holder and the other men in jail. The four women and child were all imprisoned. Three other people who had also come to visit Holder and were then imprisoned were Nicholas Davis from Plymouth, the London merchant William Robinson and a Yorkshire farmer named Marmaduke Stephenson, the latter two on a Quaker mission from England.[58][59]

The Quaker situation was becoming highly problematical for the magistrates. Their response to the increasing presence of these people was to enact tougher laws, and on 19 October 1658, a new law was passed in the Massachusetts colony that introduced capital punishment. Quakers would be banished from the colony upon pain of death, meaning they would be hanged if they defied the law. Dyer, Davis, Robinson, and Stephenson were then brought to court, and then sentenced to "banishment upon pain of death" under the new law.[60] Davis returned to Plymouth, Dyer went home to Newport, but Robinson and Stephenson remained in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, spending time in Salem.[61]

In June 1659 Robinson and Stephenson were once again apprehended and brought back to the Boston jail.[59] When Dyer heard of these arrests, she once again left her home in Newport, and returned to Boston to support her Quaker brethren, ignoring her order of banishment, and once again being incarcerated. Her husband had already come to Boston two years earlier to retrieve her from the authorities, signing an oath that she would not return. He would not come back to Boston again, but on 30 August 1659 he wrote a long and impassioned letter to the magistrates, questioning the legality of the actions taken by the Massachusetts authorities.[62]

On 19 October Dyer, Robinson and Stephenson were brought before Governor Endicott, where they explained their mission for the Lord.[63] The next day, the same group was brought before the governor, who directed the prison keeper to remove the men's hats. He then addressed the group, "We have made many laws and endeavored in several ways to keep you from among us, but neither whipping nor imprisonment, nor cutting off ears, nor banishment upon pain of death will keep you from among us. We desire not your death." Having met his obligation to present the position of the colony's authorities, he then pronounced, "Hearken now to your sentence of death."[64] William Robinson then wanted to read a prepared statement about being called by the Lord to Boston, but the governor would not allow it to be read, and Robinson was sent back to prison. Marmaduke Stephenson, being less vociferous than Robinson, was allowed to speak, and though initially declining, he ultimately spoke his mind, and then was also sent back to jail.[65]

When Dyer was brought forth, the governor pronounced her sentence, "Mary Dyer, you shall go from hence to the place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of execution, and there be hanged till you be dead." She replied, "The will of the Lord be done." When Endicott directed the marshall to take her away, she said, "Yea, and joyfully I go."[66]

First Quaker executions

The date set for the executions of the three Quaker evangelists, William Robinson, Marmaduke Stephenson and Mary Dyer, was 27 October 1659. Captain James Oliver of the Boston military company was directed to provide a force of armed soldiers to escort the prisoners to the place of execution. Dyer walked hand-in-hand with the two men, and between them. When she was publicly asked about this inappropriate closeness, she responded instead to her sense of the event: "It is an hour of the greatest joy I can enjoy in this world. No eye can see, no ear can hear, no tongue can speak, no heart can understand the sweet incomes and refreshings of the spirit of the Lord which now I enjoy."[67] The prisoners attempted to speak to the gathered crowd as they proceeded to the gallows, but their voices were drowned out by constant drum beats.[68]

The place of execution was not the Boston Common, as expressed by many writers over the years, but instead about a mile south of there on Boston Neck, near the current intersection of West Dedham Street and Washington Street. Boston Neck was at one time a narrow spit of land providing the only land access to the Shawmut Peninsula where Boston is located. Over time, the water on both sides of the isthmus was filled in, so that the narrow neck no longer exists. A possible reason for the confusion may be because the land immediately south of Boston Neck was not privately owned and considered "common lands", leading some writers to misinterpret this as being the Boston Common.[69]

William Robinson was the first of the three to mount the gallows ladder, and from there made a statement to the crowd, then died when the ladder was removed. Marmaduke Stephenson was the next to hang, and then it was Dyer's turn after she witnessed the execution of her two friends. Dyer's arms and legs were bound and her face was covered with a handkerchief provided by Reverend John Wilson who had been one of her pastors in the Boston church many years earlier.[70] She stood calmly on the ladder, prepared for her death, but as she waited, an order of a reprieve was announced. A petition from her son, William, had given the authorities an excuse to avoid her execution. It had been a pre-arranged scheme, in an attempt to unnerve and dissuade Dyer from her mission. This was made clear from the wording of the reprieve, though Dyer's only expectation was to die as a martyr.[71]

The day after Dyer was pulled from the gallows she wrote a letter to the General Court, refusing to accept the provision of the reprieve. In this letter she wrote, "My life is not accepted, neither availeth me, in comparison with the lives and liberty of the Truth and Servants of the living God for which in the Bowels of Love and Meekness I sought you; yet nevertheless with wicked Hands have you put two of them to Death, which makes me to feel that the Mercies of the Wicked is cruelty; I rather chuse to Dye than to live, as from you, as Guilty of their Innocent Blood."[72]

The courage of the martyrs led to a popular sentiment against the authorities who now felt it necessary to draft a vindication of their actions. The wording of this petition suggested that the reprieve of Mary Dyer should soften the reality of the martyrdom of the two men.[73] The Massachusetts General Court sent this document to the newly restored king in England, and in answer to it, the Quaker historian, Edward Burrough wrote a short book in 1661. In this book, Burrough refuted the claims of Massachusetts, point by point, provided a list of the atrocities committed against Quakers, and also provided a narrative of the three Quaker executions that had transpired prior to the book's publication.[74]

After going home to Rhode Island, Dyer spent most of the following winter on Shelter Island, sitting between the north and south forks of Long Island. Though sheltered from storms, the island's owner, Nathaniel Sylvester, used it as a refuge for Quakers seeking shelter from the Puritans, thus providing its name.[75] Here Dyer was able to commune with her fellow Quakers, including her Newport neighbors, William Coddington and his wife Anne Brinley, who had recently converted.[76] Dyer used her time here to mull over the vindication prepared by the Puritan authorities to send to England, concerning their actions against the Quakers. This document was an affront to Dyer, and she viewed it as merely a means to soften public outrage.[77] She was determined to return to Boston to force the authorities to either change their laws or to hang a woman, and she left Shelter Island in April 1660 focused on this mission.[78]

Dyer's martyrdom

Dyer returned to Boston on 21 May 1660 and ten days later she was once again brought before the governor. The exchange of words between Dyer and Governor Endicott was recorded as follows:

Endicott: Are you the same Mary Dyer that was here before?

Dyer: I am the same Mary Dyer that was here the last General Court.

Endicott: You will own yourself a Quaker, will you not?

Dyer: I own myself to be reproachfully so called.

Endicott: Sentence was passed upon you the last General Court; and now likewise—You must return to the prison, and there remain till to-morrow at nine o'clock; then thence you must go to the gallows and there be hanged till you are dead.

Dyer: This is no more than what thou saidst before.

Endicott: But now it is to be executed. Therefore prepare yourself to-morrow at nine o'clock.

Dyer: I came in obedience to the will of God the last General Court, desiring you to repeal your unrighteous laws of banishment on pain of death; and that same is my work now, and earnest request, although I told you that if you refused to repeal them, the Lord would send others of his servants to witness against them.[79]

Following this exchange, the governor asked if she was a prophetess, and she answered that she spoke the words that the Lord spoke to her. When she began to speak again, the governor called, "Away with her! Away with her!" She was returned to jail. Though her husband had written a letter to Endicott requesting his wife's freedom, another reprieve was not granted.[79]

Execution

On 1 June 1660, at 9 A.M., Dyer once again departed the jail and was escorted to the gallows. Once she was on the ladder, under the elm tree, she was given the opportunity to save her life. Her response was, "Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death."[80] The military commander, Captain John Webb, recited the charges against her and said she "was guilty of her own blood".[80] Dyer's response was:

Nay, I came to keep bloodguiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death, made against the innocent servants of the Lord, therefore my blood will be required at your hands who willfully do it; but for those that do is in the simplicity of their hearts, I do desire the Lord to forgive them. I came to do the will of my Father, and in obedience to his will I stand even to the death.[81][82]

Her former pastor, John Wilson, urged her to repent and to not be "so deluded and carried away by the deceit of the devil".[83] To this she answered, "Nay, man, I am not now to repent." Asked if she would have the elders pray for her, she replied, "I know never an Elder here." Another short exchange followed, and then, in the words of her biographer, Horatio Rogers, "she was swung off, and the crown of martyrdom descended upon her head".[84]

Burial

The Friends' records of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, contain the following entry: "Mary Dyer the wife of William Dyer of Newport in Rhode Island: she was put to death at the Town of Boston with ye like cruil hand as the martyrs were in Queen Mary's time, and there buried upon ye 31 day of ye 3d mo. 1660." In the calendar used at the time, May was the third month of the year, but the date in the record is incorrect by a day, as the actual date of death was 1 June.[85] Also, this entry states that Mary was buried there in Boston where she was hanged, and biographer Rogers echoed this, but this is not likely. Johan Winsser presents evidence that Mary was buried on the Dyer family farm, located north of Newport where the Navy base is now situated in the current town of Middletown. The strongest evidence found is the 1839 journal entry given by Daniel Wheeler, who wrote, "Before reaching Providence [coming from Newport], the site of the dwelling, and burying place of Mary Dyer was shown me."[86] Winsser provides other items of evidence lending credence to this notion; it is unlikely that Dyer's remains would have been left in Boston since she had a husband, many children, and friends living in Newport, Rhode Island.[86]

Aftermath

In his History of Boston, Caleb Snow wrote that one of the officers attending the hanging, Edward Wanton, was so overcome by the execution that he became a Quaker convert.[87] The Wantons later became one of the leading Quaker families in Rhode Island, and two of Wanton's sons, William and John, and two of his grandsons, Gideon and Joseph Wanton, became governors of the Rhode Island Colony.[88]

Humphrey Atherton, a prominent Massachusetts official and one of Dyer's persecutors, wrote, "Mary Dyer did hang as a flag for others to take example by."[89] Atherton died on 16 September 1661 following a fall from a horse, and many Quakers viewed this as God's wrath sent upon him for his harshness towards their sect.[90]

A strong reaction from a contemporary woman and friend of Mary Dyer came from Anne Brinley Coddington, with whom Dyer spent her final winter on Shelter Island. Anne Coddington sent a scathing letter to the Massachusetts magistrates, singling out Governor Endicott's role in the execution. In addition, her husband, William Coddington sent several letters to the Connecticut governor, John Winthrop, Jr., condemning the execution.[91]

While news of Dyer's hanging was quick to spread through the American colonies and England, there was no immediate response from London because of the political turbulence, resulting in the restoration of the king to power in 1660. One more Quaker was martyred at the hands of the Puritans, William Leddra of the Barbadoes, who was hanged in March 1661.[89] A few months later, however, the English Quaker activist Edward Burrough was able to get an appointment with the king. In a document dated 9 September 1661 and addressed to Endicott and all other governors in New England, the king directed that executions and imprisonments of Quakers cease, and that any offending Quaker be sent to England for trial under the existing English law.[92]

While the royal response put an end to executions, the Puritans continued to find ways to abuse the Quakers who came to Massachusetts. In 1661 they passed the "Cart and Tail Law", having Quakers tied to carts, stripped to the waist, and dragged through various towns behind the cart, being whipped en route, until they were taken out of the colony.[93] At about the time that Endicott died in 1665, a royal commission directed that all legal actions taken against Quakers would cease. Nevertheless, whippings and imprisonments continued into the 1670s, after which popular sentiment, coupled with the royal directives, finally put an end to the Quaker persecution.[89][94]

Modern view

According to literary scholar Anne Myles, the life of Mary Dyer "functions as a powerful, almost allegorical example of a woman returning, over and over, to the same power-infused site of legal and discursive control". The only first-hand evidence available as to the thoughts and motives of Dyer lie in the letters that she wrote. But Myles sees her behavior as "a richly legible text of female agency, affiliation, and dissent".[95] Looking at Burrough's account of the conversation between Dyer and Governor Endicott, Myles views the two most important dimensions as being agency and affiliation. The first is that Dyer's actions "can be read as staging a public drama of agency", a means for women, including female prophets, to act under the power and will of God. While Quaker women were allowed to preach, they were not being assertive when doing so because they were actually "preaching against their own wills and minds".[95]

Dyer possessed a "vigorous intentionality" in engaging with the magistrates and ministers, both in her speech and in her behavior. Even though those who chronicled her actions and life, such as Burrough and Rogers, looked at her as being submissive to the will of God, she was nevertheless the active participant in her fate, voluntarily choosing to become a martyr. She took full responsibility for her actions, while imploring the Puritan authorities to assume their moral responsibility for her death. This provides a distinguishing feature between Dyer and Anne Hutchinson, the latter of whom may not have fully comprehended the consequences of her behavior. While Dyer's husband and those unsympathetic to her labelled her as having a "madness", it is clear from her letters and her spoken words that her purpose and intentions were displayed with the utmost clarity of mind.[96]

During her dialogues, while walking to the gallows, or standing on the ladder under the hanging tree, Dyer exchanged a series of "yeas" and "nays" with her detractors. With these affirmations and negations, she was refusing to allow others to construct her meaning. She refuted the image of her as a sinner in need of repentance, and contested the authority of the elders of the church. Just like Hutchinson's befuddling of her accusers during her civil trial, Dyer did not allow her interrogators to feel assured in how they framed her meaning.[97]

While agency is the first of two dimensions of Dyer's story, the second is allegiance. Dyer became known in the public eye on the day when Anne Hutchinson was excommunicated, and Dyer took her hand while they walked out of the meeting house together. Dyer had a strong affiliation and allegiance to this older woman who shared the secret of her unfortunate birth. Likewise, two decades later she framed her acts as a means to stand by her friends and share in their fate.[97] In the first of two letters of Dyer's that have been preserved, she wrote to the General Court, "if my Life were freely granted by you, it would not avail me, nor could I expect it of you, so long as I should daily hear or see the Sufferings of these People, my dear Brethren and Seed, with whom my Life is bound up, as I have done these two years".[54] Traditional bonds for females were to spouses and children, yet in the Quaker community there were strong spiritual bonds that transcended gender boundaries. Thus the Puritan public found it very unusual that Dyer walked to the gallows hand-in-hand between two male friends, and she was asked if she was not ashamed of doing so. This spiritual closeness of the Quakers was very threatening to the Puritan mindset where allegiance was controlled by the male church members. The Quakers allowed their personal bonds to transgress not only gender lines but also the boundaries of age and class.[98]

In her first letter to the General Court, Dyer used the themes of agency and allegiance in creating an analogy between her witnessing in Massachusetts with the Book of Esther. Esther, a Jew, was called upon to save her people after the evil Haman urged the king to enact a law to have all Jews put to death. It was Esther's intercession with the king that saved her people, and the parallels are that Dyer is the beautiful Esther, with wicked Haman representing the Massachusetts authorities, and the Jews of the Bible being the Quakers of Dyer's time.[99] Ultimately, Dyer's martyrdom did have the desired effect. Unlike the story of Anne Hutchinson, that was narrated for more than a century by only her enemies, the orthodox Puritans, Dyer's story became the story of the Quakers, and it was quickly shared in England, and eventually made its way before King Charles II. The king ordered an end to the capital punishments, though the severe treatment continued for several more years.[99]

According to Myles, Dyer's life journey during her time in New England transformed her from "a silenced object to a speaking subject; from an Antinomian monster to a Quaker martyr".[100] The evidence from a personal standpoint and from the standpoint of all Quakers, suggests that Dyer's ending was as much a spiritual triumph as it was a tragic injustice.[101]

Memorials and honors

A statue was dedicated to Mary Dyer in June 1959 and is located outside the Massachusetts State House.

A bronze statue of Dyer by Quaker sculptor Sylvia Shaw Judson stands in front of the Massachusetts State House in Boston, and is featured on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail;[103] a copy stands in front of the Friends Center in central Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and another in front of Stout Meetinghouse at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana.[104][105]

In Portsmouth, Rhode Island, Mary Dyer and her friend Anne Hutchinson have been remembered at Founders Brook Park with the Anne Hutchinson/Mary Dyer Memorial Herb Garden, a medicinal botanical garden, set by a scenic waterfall with a historical marker for the early settlement of Portsmouth.[106] The garden was created by artist and herbalist Michael Steven Ford, who is a descendant of both women. The memorial was a grass roots effort by a local Newport organization, the Anne Hutchinson Memorial Committee headed by Newport artist, Valerie Debrule. The organization, called Friends of Anne Hutchinson, meets annually at the memorial in Portsmouth, on the Sunday nearest to 20 July, the date of Anne's baptism, to celebrate her life and the local colonial history of the women of Aquidneck Island.[107]

Dyer was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 1997[108] and into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 2000.[109][verification needed]

Published works

Three adult biographies of Mary Dyer have been published, the first being Mary Dyer of Rhode Island, the Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston Common, June 1, 1660 by Horatio Rogers (1896); the second being Mary Dyer: Biography of a Rebel Quaker by Ruth Plimpton (1994); and the third, Mary and William Dyer: Quaker Light and Puritan Ambition in Early New England by Johan Winsser (2017). A biography for middle-school students, Mary Dyer, Friend of Freedom by John Briggs, was published in 2014. While Dyer published no works herself, she did write two letters which have been preserved, both of them focal to her martyrdom, and both of them published in her biographies.[110][111][112]

A play titled Heretic, by Jeanmarie Simpson, about the life of Mary Dyer, was first published in 2016 under the title The Joy, by the Fellowship of Quakers in the Arts.[113] She was also featured in Rachel Dyer, an 1828 novel by John Neal that connects her martyrdom with the Salem witch trials. The title character is Dyer's fictional granddaughter, who is the last victim of the hysteria in 1692.[114][115]

Children and descendants

Mary Dyer had eight known children, six of whom grew to adulthood. Following her martyrdom, her husband remarried and had one more known child, and possibly others. Her oldest child, William, was baptized at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, on 24 October 1634 and was buried there three days later. After sailing to New England, her second child, Samuel, was baptized at the Boston church on 20 December 1635 and married by 1663 to Anne Hutchinson, the daughter of Edward Hutchinson and the granddaughter of William and Anne Hutchinson. Her third child was the premature stillborn female, born 17 October 1637, discussed earlier. Henry, born roughly 1640, was the fourth child, and he married Elizabeth Sanford, the daughter of John Sanford, Jr., and the granddaughter of Governor John Sanford.[116]

The fifth child was a second William, born about 1642, who married Mary, possibly a daughter of Richard Walker of Lynn, Massachusetts, but no evidence supports this. Child number six was a male and given the Biblical name Mahershallalhashbaz. He was married to Martha Pearce, the daughter of Richard Pearce. Mary was the seventh child, born roughly 1647, and married by about 1675 Henry Ward; they were living in Cecil County, Maryland, in January 1679. Mary Dyer's youngest child was Charles, born roughly 1650, whose first wife was named Mary; there are unsupported claims that she was a daughter of John Lippett. Charles married second after 1690 Martha (Brownell) Wait, who survived him.[116]

There is no evidence that Mary's husband, William Dyer, ever became a Quaker. There was a lot of litigation concerning the estate of William Dyer, Sr; his widow, Katherine, took both the widow of his son Samuel and later his son Charles to court over the estate, likely feeling that more of his estate belonged to his children with her.[117]

Notable descendants of Mary Dyer include Rhode Island Governors Elisha Dyer and Elisha Dyer, Jr., and U.S. Senator from Rhode Island, Jonathan Chace.[118]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Winsser 2004, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, pp. 12–13.

- ^ England, and Great Britain from 1708, used the Julian calendar until 1752. The new year in that calendar fell on Lady Day, 25 March, so dates between 1 January and 25 March are written with both years to avoid confusion.

- ^ a b Rogers 1896, p. 31.

- ^ Bishop 1661, p. 119.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 381.

- ^ a b Battis 1962, pp. 300–307.

- ^ Bremer 1995, pp. 29–32.

- ^ a b c Austin 1887, p. 290.

- ^ Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 379.

- ^ a b c Winship 2002, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Hall 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Bremer 1981, p. 4.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 105.

- ^ Bremer 1995, p. 66.

- ^ Bremer 1981, p. 5.

- ^ Winship 2002, pp. 83–89.

- ^ a b c Hall 1990, p. 7.

- ^ a b Hall 1990, p. 8.

- ^ Hall 1990, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Rogers 1896, p. 32.

- ^ a b Battis 1962, p. 211.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 212.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 33.

- ^ LaPlante 2004, p. 207.

- ^ a b c LaPlante 2004, p. 206.

- ^ Winsser 1990, p. 23.

- ^ Winsser 1990, p. 24.

- ^ Winthrop 1996, p. 254.

- ^ Winsser 1990, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Winsser 1990, pp. 22–25.

- ^ LaPlante 2004, p. 217.

- ^ Winsser 1990, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Winsser 1990, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b LaPlante 2004, p. 219.

- ^ Winsser 1990, p. 29.

- ^ a b Winsser 1990, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 231.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, p. 975.

- ^ a b Bicknell 1920, p. 976.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, p. 980.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, p. 983.

- ^ a b Bicknell 1920, p. 987.

- ^ Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 384.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 110.

- ^ a b Plimpton 1994, p. 137.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 22.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Winsser 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 4–11.

- ^ a b Rogers 1896, p. 35.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 36.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b Plimpton 1994, p. 149.

- ^ a b Rogers 1896, p. 37.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 151.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 152.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, pp. 155–159.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 40.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 41.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 44.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 48.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 50.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 54.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Burrough 1661, p. i (abstract).

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 175.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 176.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 182.

- ^ a b Rogers 1896, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b Rogers 1896, p. 60.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Sewel 1844, p. 291.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 61.

- ^ Rogers 1896, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 63.

- ^ a b Dyer's Grave 2014.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 62.

- ^ Austin 1887, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Rogers 1896, p. 67.

- ^ Woodward 1869, p. 6.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, pp. 191–194.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 204.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. 205.

- ^ a b Myles 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Myles 2001, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Myles 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Myles 2001, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Myles 2001, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Myles 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Myles 2001, pp. 15–17.

- ^ "Boston Neck Gallows, Colonial Execution Place for Quakers". Celebrate Boston. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Beacon Hill". Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

- ^ Friends Center.

- ^ Quakers in the World.

- ^ Heritage Passage.

- ^ Herald News 2011.

- ^ Inductee Details, "Mary Dyer", Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame, 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2015

- ^ "Mary Barret Dyer", National Women's Hall of Fame, 2015.

- ^ Plimpton 1994, p. i.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. i.

- ^ Briggs 2014, p. i.

- ^ Bishop, Jeanmarie (Simpson) (24 February 2019). Heretic: The Mary Dyer Story. ISBN 978-1797886107.

- ^ Carlson, David J. (2007). "'Another Declaration of Independence': John Neal's 'Rachel Dyer' and the Assault on Precedent". Early American Literature. 42 (3): 408–409. doi:10.1353/eal.2007.0031. JSTOR 25057515. S2CID 159478165.

- ^ Lease, Benjamin (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-226-46969-0.

- ^ a b Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, pp. 384–385.

- ^ Rogers 1896, p. 34.

Bibliography

Books

- Anderson, Robert C.; Sanborn, George F. Jr.; Sanborn, Melinde L. (2001). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. II C-F. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-120-5.

- Arnold, Samuel Greene (1859). History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol. 1. New York: D. Appleton & Company. OCLC 712634101.

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.

- Battis, Emery (1962). Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-0863-4.

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1920). The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol. 3. New York: The American Historical Society. OCLC 1953313.

- Bishop, George (1661). New England Judged. London.

- Bremer, Francis J. (1981). Anne Hutchinson: Troubler of the Puritan Zion. Huntington, New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. pp. 1–8.

- Bremer, Francis J. (1995). The Puritan Experiment, New England Society from Bradford to Edwards. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-0-87451-728-6.

- Briggs, John (2014). Mary Dyer, Friend of Freedom. Atombank Books. ISBN 978-0-9905160-0-2.

- Burrough, Edward (1661). Paul Royster (ed.). A Declaration of the Sad and Great Persecution and Martyrdom of the People of God, called Quakers, in New-England, for the Worshipping of God. University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Hall, David D. (1990). The Antinomian Controversy, 1636–1638, A Documentary History. Durham [NC] and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0822310910.

- LaPlante, Eve (2004). American Jezebel, the Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman who Defied the Puritans. San Francisco: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-056233-1.

- Plimpton, Ruth Talbot (1994). Mary Dyer: Biography of a Rebel Quaker. Boston, Massachusetts: Brandon Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8283-1964-2.

- Rogers, Horatio (1896). Mary Dyer of Rhode Island, the Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston Common, June 1, 1660. Providence, RI: Preston and Rounds. ISBN 9780795014628.

- Sewel, William (1844). The History of the Rise, Increase, and Progress of the Christian People Called Quakers. New York: Baker and Crane.

- Webb, Maria (1884). The Fells of Swarthmoor Hall and their Friends. Philadelphia: Henry Longstreth.

- Winship, Michael Paul (2002). Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636–1641. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08943-4.

- Winthrop, John (1996). James Savage; Richard S. Dunn; Laetitia Yaendle (eds.). The Journal of John Winthrop 1630–1649. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

- Woodward, Harlow Elliot (1869). Epitaphs from the Old Burying Ground in Dorchester. Boston Highlands.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Articles

- Canavan, Michael J. (1911). "Where Were the Quakers Hanged?". Proceedings of the Bostonian Society: 37–49.

- Myles, Anne G. (2001). "From Monster to Martyr: Re-Presenting Mary Dyer". Early American Literature. 36 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1353/eal.2001.0006. JSTOR 25057215. S2CID 162333178.

- Winsser, Johan (January 2004). "A Brother Found: A Clue to the Ancestry of Mary [Barrett] Dyer, the Quaker Martyr". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. 158: 27–28. ISBN 0-7884-0293-5.

- Winsser, Johan (Spring 1990). "Mary Dyer and the "Monster" Story". Quaker History. 79 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1353/qkh.1990.0001. JSTOR 41947156. PMID 11617992. S2CID 33156789.

Online sources

- "Anne Hutchinson Day". The Herald News. 20 July 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Boston Neck Gallows Quaker Hanging Place". Celebrate Boston. 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- "Founders Brook Park". Newport Bristol Heritage Passage. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Mary Dyer". Quakers in the World. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Mary Dyer Statue". Friends Center Philadelphia. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Winsser, Johan (27 April 2014). "Mary Dyer's Grave". Johan Winsser. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

Further reading

- Jones, Rufus M. (1911). The Quakers in the American Colonies. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- 1610s births

- 1660 deaths

- 17th-century executions of American people

- 17th century in Boston

- 17th-century Protestant martyrs

- 17th-century Quakers

- Colonial American women

- English emigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony

- American Quakers

- Converts to Quakerism

- Executed American women

- People executed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony

- People from colonial Boston

- People from Portsmouth, Rhode Island

- People executed by the Thirteen Colonies by hanging

- Quaker ministers

- People of colonial Rhode Island

- Quakers executed in colonial America

- Dyer family