History of Périgueux: Difference between revisions

m Substing templates: {{Lien web}} and {{Ouvrage}}. See User:AnomieBOT/docs/TemplateSubster for info. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- Important, do not remove this line before article has been created. -->[[File:Blason ville fr Périgueux (Dordogne).svg|alt=Diagram of a coat of arms.|thumb|Current coat of arms of the city of Périgueux.]] |

<!-- Important, do not remove this line before article has been created. -->[[File:Blason ville fr Périgueux (Dordogne).svg|alt=Diagram of a coat of arms.|thumb|Current coat of arms of the city of Périgueux.]]{{Short description|historical events associated with Périgueux.}} |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

In 27 BC, when [[Augustus]] reorganized the administration of [[Gallia]], Périgueux became part of the [[Protohistoric Aquitaine|province of Aquitaine]].<ref>{{cite web|access-date=September 22, 2012|language=fr|title=Noms antiques des villes & peuples de l'Aquitaine|url=http://www.lexilogos.com/gaulois_toponymie_aquitaine.htm|website=Lexilogos}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.</ref> The oppidum of ''La Boissière'' was abandoned and the Gallo-Roman city ''[[municipium]]'' [[Vesunna (Périgueux)|Vesunna]], future Périgueux, was created between 25 and 16 BC in a loop on the right bank of the Isle.<ref name="Penaud573">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=573-574}}.</ref> It benefited from Roman public power.<ref>{{harvsp|Moreau|1775|p=20}}.</ref> At that time, Vesunna was one of twenty-one cities in the [[Gallia Aquitania|province of Aquitaine]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Cocula|2011|p=29}}.</ref> |

In 27 BC, when [[Augustus]] reorganized the administration of [[Gallia]], Périgueux became part of the [[Protohistoric Aquitaine|province of Aquitaine]].<ref>{{cite web|access-date=September 22, 2012|language=fr|title=Noms antiques des villes & peuples de l'Aquitaine|url=http://www.lexilogos.com/gaulois_toponymie_aquitaine.htm|website=Lexilogos}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.</ref> The oppidum of ''La Boissière'' was abandoned and the Gallo-Roman city ''[[municipium]]'' [[Vesunna (Périgueux)|Vesunna]], future Périgueux, was created between 25 and 16 BC in a loop on the right bank of the Isle.<ref name="Penaud573">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=573-574}}.</ref> It benefited from Roman public power.<ref>{{harvsp|Moreau|1775|p=20}}.</ref> At that time, Vesunna was one of twenty-one cities in the [[Gallia Aquitania|province of Aquitaine]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Cocula|2011|p=29}}.</ref> |

||

It was in the 1st century AD that the city, as a Roman |

It was in the 1st century AD that the city, as a Roman town, underwent its greatest expansion, mainly in terms of urban planning, where the largest public monuments were built according to Roman plans, such as the [[Roman Forum|forum]], the [[amphitheatre]] and the [[thermae]].<ref name="Lachaise73">{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=73}}.</ref> Throughout the 1st century, urban construction continued, not only enlarging existing buildings but also building more and more [[domus]].<ref name="Lachaise73" /> At the end of the 2nd century, following an invasion attributed to the [[Alemanni]], the Roman city shrank to five and a half hectares,<ref name="Penaud122">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=122-123}}.</ref> retreating to a small plateau behind [[Rampart (fortification)|ramparts]]<ref>{{cite web|access-date=15 September 2012|date=28 January 2010|title=Petit tour d’horizon de la Ville|url=http://perigueux.fr/bienvenue-a-perigueux/537-histoire-de-la-ville.html#c551|website=le site de la mairie de Périgueux}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.</ref> built between 276 and 290.<ref name="Penaud113" /> Incorporating the north-western half of the [[Périgueux Amphitheatre|Vesunna amphitheatre]],<ref name="Penaud122" /> these walls were built using elements of the city's monuments (remnants of the ramparts remain), and this third city took the name ''Civitas Petrucoriorum'' ("city of the Petrocorii"),<ref name="Penaud573" /> the place that was to become "the Cité" (lit. french for "the town").<ref name="Penaud120">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=120-121}}.</ref> At the time, this enclosure comprised twenty-four [[Fortified tower|towers]], twenty-three [[Curtain wall (fortification)|curtain walls]] and four [[City gate|gates]], of which only two remain today: the Porte Normande and the Porte de Mars.<ref name="Penaud122" /><ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=103}}.</ref> |

||

According to the [[geographer]] [[Strabo]], the [[Petrocorii]] worked extensively with [[iron]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=94}}.</ref> |

According to the [[geographer]] [[Strabo]], the [[Petrocorii]] worked extensively with [[iron]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=94}}.</ref> |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==== Frankish domination by the Salians ==== |

==== Frankish domination by the Salians ==== |

||

Following the [[fall of the Western Roman Empire]], the [[Franks]] came to dominate the region in the late 5th century. As a result, the |

Following the [[fall of the Western Roman Empire]], the [[Franks]] came to dominate the region in the late 5th century. As a result, the Cité became [[Christianity|Christian]] in the 6th century, even though the spread of religion had already reached a large part of urban society.<ref name="Lachaise112">{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=112}}.</ref> |

||

During the reign of the [[Merovingian dynasty|Merovingians]], the territory passed from hand to hand, provoking numerous disputes over the division of inheritance between the descendants of [[Clovis I|Clovis]] after his death in 511. [[Childebert I]] inherited first, until his death in 558, after which the lands of [[Charibert I]] in 561, then those of [[Guntram]] in 567, became part of the Vesone territory. With the help of the Church and the people of Vesone, Gontran defended the city against the violent attacks of his brother [[Chilperic I]] and [[Chlothar I|Chlothar I's]] bastard son [[Gundoald]].<ref name="Lachaise112" /> |

During the reign of the [[Merovingian dynasty|Merovingians]], the territory passed from hand to hand, provoking numerous disputes over the division of inheritance between the descendants of [[Clovis I|Clovis]] after his death in 511. [[Childebert I]] inherited first, until his death in 558, after which the lands of [[Charibert I]] in 561, then those of [[Guntram]] in 567, became part of the Vesone territory. With the help of the Church and the people of Vesone, Gontran defended the city against the violent attacks of his brother [[Chilperic I]] and [[Chlothar I|Chlothar I's]] bastard son [[Gundoald]].<ref name="Lachaise112" /> |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

Around 1040, Périgueux was troubled by unrest over the coinage minted by the [[List of Counts of Périgord|Count of Périgord]], Hélie II.<ref name="Dessalles6">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=6}}.</ref> Shortly afterwards, the bishop Girard of Gourdon considered the coin to be defective and of poor quality, and banned it. Count Aldebert II, son of Hélie II, decided to prove, by force of arms, that it was suitable for him.<ref name="Dessalles6" /><ref name="Dessalles7">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=7}}.</ref> As a result, the town had to wage a long and bloody war against the Count.<ref name="Dessalles7" /> The few dwellings under the protection of the new religious establishment of Puy-Saint-Front were burnt down around 1099; the convent and town were soon rebuilt.<ref name="Dessalles82" /> |

Around 1040, Périgueux was troubled by unrest over the coinage minted by the [[List of Counts of Périgord|Count of Périgord]], Hélie II.<ref name="Dessalles6">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=6}}.</ref> Shortly afterwards, the bishop Girard of Gourdon considered the coin to be defective and of poor quality, and banned it. Count Aldebert II, son of Hélie II, decided to prove, by force of arms, that it was suitable for him.<ref name="Dessalles6" /><ref name="Dessalles7">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=7}}.</ref> As a result, the town had to wage a long and bloody war against the Count.<ref name="Dessalles7" /> The few dwellings under the protection of the new religious establishment of Puy-Saint-Front were burnt down around 1099; the convent and town were soon rebuilt.<ref name="Dessalles82" /> |

||

Pilgrims flocked to the site of [[Front de Périgueux|Saint Front]]'s relics.<ref>{{cite book|date=1987|first1=Jean-Luc|first2=Michel|first3=Guy|isbn=2-85882-842-3|language=fr|last1=Aubarbier|last2=Binet|last3=Mandon|location=Rennes|page=39|publisher=[[Ouest-France]]|title=Nouveau guide du Périgord-Quercy}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.</ref> In the 11th century, the number of houses increased and the settlement grew ever larger.<ref name="Dessalles82" /> Over time, however, the town's inhabitants became increasingly divided. Around 1104, the burghers and citizens of the two neighboring communes came to blows; in the midst of this struggle, the burghers murdered Pierre de Périgueux, a descendant of a very old family of the Cité, and threw him into the [[Isle (river)|Isle]] river.<ref>{{cite book|date=December 1999|first1=Guy|isbn=2-86577-214-4|language=fr|last1=Penaud|location=Périgueux|page=736|publisher=Fanlac editions|title=Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.</ref> Around 1130, in a quarrel with the convent, some of the burghers of Puy-Saint-Front allied themselves with Count Hélie-Rudel.<ref name="Dessalles9">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=9}}.</ref> He was convinced that, having conquered Puy-Saint-Front, it would be easier for him to finally subdue the |

Pilgrims flocked to the site of [[Front de Périgueux|Saint Front]]'s relics.<ref>{{cite book|date=1987|first1=Jean-Luc|first2=Michel|first3=Guy|isbn=2-85882-842-3|language=fr|last1=Aubarbier|last2=Binet|last3=Mandon|location=Rennes|page=39|publisher=[[Ouest-France]]|title=Nouveau guide du Périgord-Quercy}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.</ref> In the 11th century, the number of houses increased and the settlement grew ever larger.<ref name="Dessalles82" /> Over time, however, the town's inhabitants became increasingly divided. Around 1104, the burghers and citizens of the two neighboring communes came to blows; in the midst of this struggle, the burghers murdered Pierre de Périgueux, a descendant of a very old family of the Cité, and threw him into the [[Isle (river)|Isle]] river.<ref>{{cite book|date=December 1999|first1=Guy|isbn=2-86577-214-4|language=fr|last1=Penaud|location=Périgueux|page=736|publisher=Fanlac editions|title=Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.</ref> Around 1130, in a quarrel with the convent, some of the burghers of Puy-Saint-Front allied themselves with Count Hélie-Rudel.<ref name="Dessalles9">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=9}}.</ref> He was convinced that, having conquered Puy-Saint-Front, it would be easier for him to finally subdue the Cité, something none of his ancestors had managed to do.<ref name="Dessalles9" /> At the same time, the counts dominated Puy-Saint-Front.<ref name="Dessalles9" /> |

||

==== Loyalty to the throne of England or the king of France? ==== |

|||

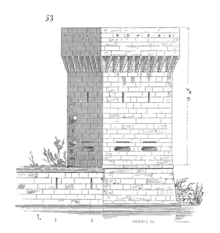

[[File:Tour.Puy.Saint.Front.Perigueux.png|alt=Drawing of a square tower.|thumb|Drawing of a square tower belonging to the ancient Puy-Saint-Front defense system, rebuilt to house fire hydrants on the first floor.]] |

|||

Around 1150, Boson III, known as de Grignols, had a large, fortified tower built to command and watch over the Cité, which he had just seized.<ref name="Dessalles10">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=10}}.</ref> But this attempt at oppression proved fatal for him and his descendants, as it aroused the anger of King [[Henry II of England]], who had become [[Duke of Aquitaine]] by marriage.<ref name="Dessalles10" /> The tower was destroyed in 1182, when, following a treaty with Count Helie V, Puy-Saint-Front fell into the hands of Henry II's son, [[Richard I of England|Richard]], who had all the fortifications built by him and his predecessor demolished.<ref name="Dessalles10" /> At the same time, at the end of the 11th century, the "bourg du Puy-Saint-Front" (town of Puy-Saint-Front) was organized as a municipality.<ref>{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=305-306}}.</ref> |

|||

Having confiscated the [[Duchy of Aquitaine]] from [[John, King of England|John Lackland]] and reunited it with the [[List of French monarchs|crown of France]], [[Philip II of France|Philip Augustus]] demanded that the peoples and lords of this duchy pay him homage. In 1204, Hélie V and the inhabitants of the future city of Périgueux swore loyalty to the French monarch.<ref>{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=11}}.</ref> |

|||

==== Background to the treaty of alliance and the founding of Périgueux ==== |

|||

For many years, Puy-Saint-Front and the counts lived in harmony.<ref name="Dessalles12">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=12}}.</ref> The town's municipal organization had long been recognized and established by royal authority.<ref name="Dessalles12" /> As for the Cité, it encountered no difficulties with the counts.<ref name="Dessalles12" /> A first agreement between the two urban centers was established in 1217.<ref name="Penaud113" /> The state of peace lasted until 1239, and there was even a degree of trust between Count Archambaud II and the town. At that time, the latter paid him 50 [[Pound (currency)|pounds]] in exchange for relinquishing the annual rent of 20 pounds it owed him each [[Christmas]].<ref name="Dessalles12" /> |

|||

To ensure mutual protection and assistance, and to put an end to rivalries, Périgueux was founded in 1240 as a result of a treaty to unite<ref>« Traité de réunion de la Cité et de la ville de Périgueux (année 1240) », dans ''Le chroniqueur du Périgord et du Limousin'' (in French), 1854, p{{p.|45-47}} [https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k200291g/f48.item (''read online'')]</ref> the two towns located just a few hundred meters apart:<ref>{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=13}}.</ref> the Cité - derived from the Gallo-Roman [[Vesunna (Périgueux)|Vésone]] - the town of the [[bishop]] and the Count of [[Périgord]],<ref name="Penaud120" /> and the middle-class town of Puy-Saint-Front.<ref name="Penaud424" /> |

|||

==== Renewed noble conflicts in Périgord ==== |

|||

Hostilities between the [[List of Counts of Périgord|Counts of Périgord]] and the new town lasted until 1250, when [[Bishop]] Pierre III de Saint-Astier<ref name="Dessalles15">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=15}}.</ref> put an end to the discord. In the 13th century, new bourgeois settled in Périgueux to increase their land holdings by buying up vacant plots, while taking advantage of the privileged relationships they maintained with their parishes of origin, where they still kept properties.<ref name="Marty71">{{Harvsp|Marty|1993|p=71}}.</ref> Returning to the region of their ancestors, cloth merchants also settled in Périgueux, acquiring numerous rents and lands in a wide radius around the city.<ref name="Marty71" /> Count Archambaud III had further disputes with Périgueux: in 1266, over the manufacture of coins, and in 1276 over their value.<ref name="Dessalles15" /> This power struggle continued from generation to generation.<ref name="Dessalles55">{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=55}}.</ref> In principle, the counts claimed sovereign power, claiming to be the sole owners of the town of Puy-Saint-Front from the seventeenth century, then seeking royal favor in the fourteenth century.<ref name="Dessalles55" /> These long conflicts came to an end in the 14th century, when the Count of Périgord, Roger-Bernard, son of Archambaud IV,<ref>{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=56}}.</ref> became the vassal of the English, who confirmed the possessions and jurisdiction<ref>{{Ouvrage|prénom1=Clément|nom1=Maur Dantine|titre=L'Art de vérifier les dates des faits historiques, des chartes, des chroniques et autres ancien monumens, depuis la naissance de Notre-Seigneur|tome=2|lieu=Paris|éditeur=Alexandre Jombert|année=1784|numéro d'édition=|passage=384|lire en ligne=https://books.google.fr/books?id=-q7XQKkWya0C&pg=PA384&dq=%22roger+bernard%22+comte+de+p%C3%A9rigord|language=fr}}.</ref> of the bourgeois of Périgueux (" Mayors, Consuls & Citizens of the City "), and [[Charles VI of France|Charles VI]] sent troops to their aid, after the bourgeois had been appealing to the royal justice system for more than eight years.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=178}}.</ref> |

|||

=== Late Middle Ages === |

|||

[[File:Edward The Black Prince - Cassell.jpg|alt=Dummy portrait of the Black Prince.|thumb|''Cassell's History of England'', 1902. Dummy portrait of the [[Edward the Black Prince|Black Prince]].]] |

|||

On April 16, 1321, a large number of [[lepers]] from the surrounding area were interned in Périgueux, then tortured before being either burned (the men) or walled up alive (the women).<ref>{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=291-292}}.</ref> In 1347, a flood on the Isle swept away part of the walls of Puy-Saint-Front.<ref name="Penaud152">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=152-153}}.</ref> From the middle of the 14th century, the countryside around Périgueux went through a period of serious crisis, marked in particular by a sharp fall in population due to the devastating effects of the [[Black Death]] and the [[Hundred Years' War]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=71}}.</ref> During the Hundred Years' War, Périgueux remained loyal to the [[Kingdom of France]], even when it was occupied by the English between 1360 and 1363.<ref>{{Harvsp|Dessalles|1847|p=75}}.</ref> In those years, the people of Périgueux submitted to the authority of [[Edward Of Woodstock|Edward of Woodstock]], nicknamed the Black Prince, who effectively levied the "fouage" ([[hearth tax]]) to feed the coffers of the principality of Aquitaine;<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=169}}.</ref> in 1367 alone, the town faced three ''[[Taille|tailles]]'' and five hearth taxes.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=170}}.</ref> During this period, the counts and their descendants, most of whom lived in their castle at [[Montignac-Lascaux|Montignac]], pledged their allegiance to the [[kingdom of England]]. [[Charles VI of France|Charles VI]] confiscated their lands and titles in favour of his brother [[Louis I, Duke of Orléans|Louis d'Orléans]]. By transfer or marriage to the [[Duke of Orléans|Orleans family]], [[Périgord]] passed into the hands of the [[House of Châtillon]] in 1437, then into the [[Albret|House of Albret]] in 1481. |

|||

The shortage of manpower led to a contraction in cultivated land, with "deserts"<ref>{{Harvsp|Marty|1993|p=76}}.</ref> appearing at the very heart of the vineyards in the parish of Saint-Martin. In the 15th century, the town's activity picked up again and was dominated by merchants, as illustrated by the construction of ''[[Hôtel particulier|Hôtels particuliers]]''.<ref name="Delattre" /> |

|||

== Modern times == |

|||

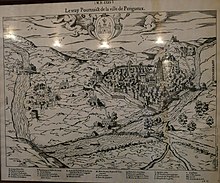

[[File:Périgueux vray pourtraict.JPG|alt=Typolithography from the Middle Ages.|thumb|''Le vray Pourtraict de la ville de Perigueux'', drawing from 1575, typolithographed by [[Auguste Dupont (France)|Auguste Dupont.]]]] |

|||

In May 1472, King [[Louis XI]] confirmed the town's privileges in his [[letters patent]], following the death of his brother [[Charles of Valois, Duke of Berry|Charles, Duke of Guyenne]].<ref>''Lettres patentes de Louis XI, Saintes, mai 1472'' in Eusèbe de Laurière, ''Ordonnances des Rois de France de la troisièmme Race'' (in French)'', recueillies par ordre chronologique'', imprimerie royale, 1820, {{p.|497}} [https://books.google.fr/books?id=OJ-b2-CLz7EC&pg=PA497 (read online)].</ref> |

|||

In 1524, the town suffered a terrible [[Plague (disease)|plague]] [[epidemic]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=200}}.</ref> In 1530, the town's consuls decided to build a college. To this end, on 7 October 1531, the mayor and consuls bought the house of Pierre Dupuy. The college was mentioned in 1574 in [[François de Belleforest]]'s ''Cosmographie universelle de tout le monde''.<ref>de Belleforest, François, ''Cosmographie universelle de tout le monde'' (in French), in Michel Sonnius, Paris, 1575, [https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k54510n/f511.image (''lire en ligne'')]</ref> Jesuits expelled from Bordeaux arrived in Périgueux in July 1589. An agreement was signed on 23 December 1591 between the city authorities and Father Clément, provincial of the Jesuits. On 23 April 1592, [[Claudio Acquaviva]], General of the Jesuits, approved an agreement concerning the new house of education entrusted to the Jesuits. The college was founded a second time on 9 October 1592.<ref>Lambert, Ch., « Le Collège de Périgueux, des origines à 1792 » (in French), dans ''Bulletin de la [[Société historique et archéologique du Périgord]]'', 1927, tome 54, p{{p.|72-85}} [https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k121796g/f73 (''read online'')]</ref> |

|||

Taxes continued to rise, in particular the ''[[gabelle]]'', which became unbearable for the inhabitants of Périgueux, so much so that they revolted in 1545.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=201}}.</ref> |

|||

The [[French Wars of Religion|Wars of Religion]] were more deadly for Périgueux than the Hundred Years' War. Périgueux was taken on 6 August 1575 by Calvinists<ref name="HistoireLarousse">{{Lien web|url=http://www.larousse.fr/archives/grande-encyclopedie/page/10447|titre=Archive Larousse : Grande Encyclopédie Larousse - Périgueux|site=le site des éditions Larousse|consulté le=September 22, 2012|language=fr}}.</ref><ref name="Penaud369" /> under the command of Favas and [[Guy of Montferrand]], then pillaged and occupied.<ref name="Penaud223-226">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=223-226}}.</ref> Their [[strategy]] was to enter the town with soldiers disguised as peasants.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=210}}.</ref> That same year, in Puy Saint-Front, the [[shrine]] and [[reliquary]] containing the remains of the [[Front of Périgueux|holy bishop]] were stolen and taken to [[Château de Tiregand]], where the saint's bones were thrown into the [[Dordogne (river)|Dordogne]].<ref name="Penaud223-226" /> Périgueux remained in Protestant hands for six years, until 1581,<ref name="Penaud113" /> when Captain Belsunce, governor of the town, allowed it to be taken by the [[Catholicism|Catholic]] Jean de Chilhaud. Périgord became part of the French crown in 1589, when its last Count, the son of [[Jeanne d'Albret]], became King of France under the name of [[Henry IV of France|Henri IV]]. |

|||

In the seventeenth century, during the reign of [[Louis XIII]], the town was on the border of a region that was subject to rebellion, extending as far south as the territory that is now the Dordogne department.<ref name="Marty105">{{Harvsp|Marty|1993|p=105}}.</ref> In 1636, during the [[Croquant rebellions]], Périgueux was the scene of peasant revolts, but was not one of the towns or castles, such as [[Grignols, Gironde|Grignols]], [[Excideuil]] and then [[Bergerac, Dordogne|Bergerac]], that were taken by peasants during this period.<ref name="Marty105" /> Their aim was to bring 6,000 men into Périgueux, steal the [[Cannon|cannons]] and pursue the ''[[Gabelle|gabeleurs]]''. On 1 May, the town was repatriated behind its ramparts and resisted the attackers. The large peasant army guarded the town day and night and stayed around the fortifications for three weeks, barricading the bridge to prevent the arrival of the troops of [[Jean Louis de Nogaret de La Valette]], [[Duke of Épernon]], commanded by his son [[Bernard de Nogaret de La Valette d'Épernon|Bernard de Nogaret de La Valette]]. La-Mothe-La-Forêt, the obscure gentleman who led this army of "communes", was finally victorious when the [[Consensus decision-making|consensus]] declared a peasant payroll.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=|pages=220-221}}.</ref> |

|||

In October 1651, during the [[The Fronde|Fronde]], Périgueux welcomed the troops of the [[Louis, Grand Condé|Prince of Condé]].<ref name="Penaud222">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=222}}.</ref> In August 1653, during the [[The Fronde|Lorraine War]], it was the only town in the south-west to remain hostile to the King, a situation that lasted until the following 16 September, when its inhabitants threw out the rebels.<ref name="Penaud222" /> In gratitude, the town's [[Magistrate|magistrates]] officially granted their wishes, leading to a [[pilgrimage]] to Notre-Dame-des-Vertus.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=September 2013 |title=Pèlerinage de Notre-Dame de Sanilhac |journal=PERIZOOM |language=fr |issue=96 |page=6}}.</ref> In 1669, the cathedral was moved from the ruined [[Saint-Étienne-de-la-Cité church|Saint-Étienne-de-la-Cité]] to [[Périgueux Cathedral|Saint-Front cathedral]], the former church of the abbey of the same name.<ref>{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=465}}.</ref> In autumn 1698, the misery of recent years had become unbearable, prompting the bishop of Périgueux to appeal to "the King's kindness".<ref>{{Harvsp|Marty|1993|p=121}}.</ref> |

|||

On 5 and 6 March 1783, the town experienced one of the highest floods of the Isle. The water rose to 5.21 metres, the highest level ever recorded for Périgueux,<ref name="SO31-12-2014">Mankowski, Thomas, ''Le jour où l'Isle a noyé la ville'' (in French), [[Sud Ouest]] édition Périgueux of December 31, 2014, p{{p.|12-13}}.</ref> drowning the causeway of the Pont Saint-Georges.<ref name="Penaud152" /> In 1789, the [[clergy]], [[nobility]] and [[Estates of the realm|third estate]] came from all over the province to elect their deputies to the [[Estates General of 1789|Estates-General]]. After the creation of the départements in 1790, the departmental assembly met alternately in [[Bergerac, Dordogne|Bergerac]], Périgueux and [[Sarlat-la-Canéda|Sarlat]]. Périgueux became the official [[Administrative centre|capital]] of the [[Dordogne]] in September 1791.<ref>{{Lien web|auteur=Préfecture de la Dordogne|url=http://www.dordogne.pref.gouv.fr/sections/la_dordogne/presentation6314/quelques_mots_sur.../view|titre=Le cadre administratif : de la province à la région|consulté le=18 septembre 2012|language=fr}}.</ref> |

|||

== Contemporary times == |

|||

=== 19th century === |

|||

==== From the First Empire to the July Monarchy ==== |

|||

The [[Napoleonic Wars]] mobilised many young people in Périgueux. The wars also provided an opportunity for a number of prominent figures to shine, including General [[Pierre Daumesnil]], Marquis [[Antoine Pierre Joseph Chapelle]] and Marshal [[Thomas Robert Bugeaud|Thomas-Robert Bugeaud.]] This mobilisation and requisitioning led to an increase in taxes. Most of the [[Conscription|conscripts]] from Périgord died on the battlefield and the few men who returned were permanently wounded. As a result, numerous protests took place in front of the [[Dordogne prefecture]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=|pages=253-254}}.</ref> |

|||

Under the [[First French Empire|First Empire]], the town, seat of the prefecture,<ref>{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=|pages=412-414}}.</ref> was enlarged in 1813 by merging with the former commune of [[Saint-Martin (Périgueux)|Saint-Martin]].<ref name="G491">{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=491}}.</ref> |

|||

In 1815, the [[Chamber of Deputies (Restoration)|deputies]] from the Périgord were mostly in the ranks of the [[Ultra-royalist|Ultras]], facing the small number of liberal monarchists elected from 1824 onwards: the Dordogne was thus more in opposition to the [[ministry of Joseph de Villèle]]. At the end of the [[1820s]], they supported the [[Ministry of Jean-Baptiste de Martignac|Jean-Baptiste de Martignac ministry]] and then opposed that of [[Jules de Polignac]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=|pages=254-255}}.</ref> In December 1836, a major flood of the river Isle swept away the dam at the Saint-Front mill by around twenty metres (70 to 80 feet), and on January 15 1843, the river reached a level comparable to the record flood of 1783.<ref name="Penaud152" /> |

|||

==== Second Republic ==== |

|||

In the [[presidential election of 1848]], the people of Périgueux voted overwhelmingly for [[Napoleon III]] (88.5% of the votes cast). <ref group="Note">At the time, the [[Dordogne]] was one of the most [[Bonapartism|Bonapartist]] departments in France.</ref>After the [[1851 French coup d'état|coup d'état of 1851]], the [[Second French Empire|proclamation of the Second Empire]] on December 2 was widely approved in Périgueux; 78% of the population of the département said "yes" in 1851 and 78.3% in 1852. The people of Périgueux remained strongly attached to the Bonapartist regime, always electing the candidates officially declared by the Emperor.<ref group="Note">Among them were [[Thomas Dusolier]], [[Timoléon Auguste Sydney Taillefer|Timoléon Taillefer]], [[Paul Dupont]] and [[Samuel Welles de Lavalette]].</ref> In the [[1870 French constitutional referendum|plebiscite of May 8 1870]], 77.7% of registered voters in the Dordogne approved the liberalisation of the regime.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=257-259}}.</ref> |

|||

==== Belle Époque ==== |

|||

[[File:Cathedrale-saint-front-périgueux-avant-restauration.jpg|alt=Black and white photograph of Saint-Front cathedral.|thumb|[[Périgueux Cathedral|Saint-Front cathedral]] before its restoration by [[Paul Abadie]]. Photo taken by [[Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement|Médéric Mieusement]] before 1893.]] |

|||

Following the merger of [[Saint-Martin (Périgueux)|Saint-Martin]] and Périgueux in 1813,<ref>{{Cassini-Ehess|id=33261|titre=Saint-Martin|consulté le=2021-07-15}}</ref> the town's population doubled in around forty years (13,547 inhabitants were recorded in 1851).<ref>{{Cassini-Ehess|id=26489|titre=Périgueux|consulté le=2021-07-15}}</ref> The town was boosted by advances in river and road transport. The fact that Périgueux had been chosen as a prefecture led to an increase in the number of [[Civil service|civil servants]], [[Professional|professionals]], [[Trade|trades]] and [[Public service|public services]]. In terms of economic growth, [[Périgueux]] overtook [[Bergerac, Dordogne|Bergerac]], until then the leading town in Périgord.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=250}}.</ref> However, its main economic activity remained [[agriculture]] until the 20th century.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=260}}.</ref> |

|||

In 1857, Périgueux saw the arrival of the railway from [[Coutras]]<ref>{{Lien web|url=http://perigueux.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/02-MA-MAIRIE-PRATIQUE/02-05-publications-de-la-ville/PDF/mag9SiteInt.pdf|titre=L'aventure du rail|format=pdf|site=le site de la mairie de Périgueux|série=[[Périgueux le magazine des Périgourdins]], {{n°}}9|mois={{4e}} trimestre|année=2010|page=34|en ligne le=14 octobre 2010|consulté le=18 septembre 2012}}.</ref> and, from 1862, the installation of repair workshops for the locomotives and carriages of the [[Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Orléans|Compagnie du Paris-Orléans]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Penaud|2003|p=50-51}}.</ref> This activity still survives in the Toulon district at the beginning of the 21st century. The [[Coutras to Tulle line|Périgueux-Coutras line]] was supplemented by links to [[Brive-la-Gaillarde]] in 1860, [[Limoges]] in 1862 and [[Agen]] in 1863, making it the town in the Dordogne with the most rail connections.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=259}}.</ref> It was also in the 19th century that two architects worked in Périgueux. Louis Catoire built the [[Périgueux courthouse|Courthouse]], the Coderc covered market and the Theatre - which has now disappeared - as well as various buildings on Place Bugeaud.<ref>{{Ouvrage|langue=fr|prénom1=Guy|nom1=Penaud|lien auteur1=Guy Penaud|titre=Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord|lieu=Périgueux|éditeur=[[éditions Fanlac]]|année=1999|mois=décembre|pages totales=959|passage=204|isbn=2-86577-214-4}}.</ref> [[Paul Abadie]] restored [[Périgueux Cathedral|Saint-Front cathedral]].<ref>{{Ouvrage|prénom1=Claude|nom1=Laroche|titre=Saint-Front de Périgueux|sous-titre=la restauration au {{s-|XIX|e}}|éditeur=|année=|passage=267-280|isbn=}}, dans {{Ouvrage|titre=Congrès archéologique de France|sous-titre={{156e}} session - Monuments en Périgord - 1999|lieu=Paris|éditeur=Société Française d'Archéologie|année=1999|isbn=}}.</ref> |

|||

Périgueux became increasingly depopulated between 1866 and 1911, as the people of the region were drawn to [[metropolis]] such as [[Bordeaux]] and [[Paris]]. This led to a decline in the local population, taking into account the [[Franco-Prussian War|Franco-Prussian war of 1870]] and the low [[birth rate]], which was exceeded by the [[Mortality rate|death rate]]. Nevertheless, the population grew, balanced by high [[emigration]].<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=261-262}}.</ref> |

|||

From the 1880s onwards, Périgueux experienced a decline in the old iron and [[steel industry]], supported by the wine crisis. Industrial [[productivity]] collapsed, but the modern systems of the [[Second Industrial Revolution|second industrial revolution]] were unable to offset this deficit.<ref>{{Harvsp|Lachaise|2000|p=263}}.</ref> |

|||

{{Gallery |

|||

|align=center |

|||

|height=200 |

|||

|File:Faubourg des Barris alimentation.jpg |

|||

|alt1=Black and white view of a three-arched bridge over a river, with a hilly town in the background. |

|||

|The Barris suburb in 1860. |

|||

|File:Périgueux à l'âge industriel.JPG |

|||

|alt2=Map of the town of Périgueux in 1880. |

|||

|Périgueaux in 1880 |

|||

|Périgueux à l'âge industriel (2).jpg |

|||

|alt3=Map of the town of Périgueux in 1899. |

|||

|Périgueaux in 1899 |

|||

|File:Faubourg des Barris panorama, plaine du Petit Change.jpg |

|||

|alt4=Panorama of the Barris suburb and the Petit Change plain. |

|||

|The Barris suburb in 1909 (on the right, in the plain). |

|||

}} |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 14:44, 13 September 2023

The history of Périgueux catalogues, studies and interprets all the events, both ancient and more recent, associated with this French town.

Although Périgueux has been inhabited since prehistoric times, the first city, named Vesunna, dates back to ancient Rome. Under the Roman Empire, Périgueux became a powerful city in Gallia Aquitania . During the barbarian invasions, Vesunna was destroyed around 410. A new fortified center, called Puy-Saint-Front, developed towards the end of the 10th century. Until the 13th century, political power was entirely in the hands of the bishop, who jealously guarded his town's autonomy. It wasn't until 1250 that the bourgeoisie began to counterbalance his authority, a century before the town finally submitted to the kingdom of France.

During the Renaissance, Périgueux continued to develop, becoming a commercial crossroads for the region. But this first golden age was cut short by the Wars of Religion, during which many merchants were pillaged. During the absolute monarchy, Périgueux remained a modest city in France, whose main asset was its position as a commercial crossroads. Under the French Revolution, the city officially became the administrative centre of the Dordogne department.

It wasn't until the reign of Napoleon that the town experienced an urban boom, merging with the commune of Saint-Martin in 1813. The Belle Époque saw the rise of numerous industries - notably metallurgy and railroad workshops. World War II saw Périgueux, located in the Zone Libre, become the center of several Resistance networks.

After the war, Périgueux quickly recovered its urban, economic and political standing.

Prehistory

It was during the Acheulean and, above all, the Mousterian periods that the first human settlements appeared on the site of present-day Périgueux, at the foot of the plateau almost encircled by the River Isle.[1] Various sites from this period have been uncovered in the Périgueux area, notably at Sept Fonts (right bank),[2] Croix du Duc, Gour de l'Arche, Jambes, Petit-Puy-Rousseau, Toulon, and north of the Tourny alleys.[3] The Isle valley attracted animal and human populations thanks to its diverse resources, including flint-rich limestone massifs and caves that could be used as shelters.[4]

Located above the important Toulon spring, the Jambes site yielded evidence of the Upper Perigordian.[5]

Ancient times

In 700 B.C., the Isle valley was occupied by the Ligures, who were driven out around 500 B.C. by the Iberians.[6]

Around 200 BC, "the Petrocorii inhabited the region between the Dordogne and Vézère rivers", according to Venceslas Kruta.[7] During this period, they settled on the heights on the left bank of the Isle river, creating a fortified camp on the hills of Écornebœuf[8] and Boissière, in what is now Coulounieix-Chamiers, a fortified camp at La Boissière, also known as "Caesar's camp at Curade".[9][10] Between the two hills lies the sacred fountain of Les Jameaux,[11] probably dedicated to Ouesona, the mother-goddess who, according to Claude Chevillot, protected the beneficial waters. The Petrocorii were settled in Gallia, not Aquitaine, because before the Roman conquest, these two territories were separated by the Garumna river.[12]

In 52 BC, Vercingetorix asked the Petrocii to send 5,000 warriors to help him face Julius Caesar's Roman legions.[13]

In 27 BC, when Augustus reorganized the administration of Gallia, Périgueux became part of the province of Aquitaine.[14] The oppidum of La Boissière was abandoned and the Gallo-Roman city municipium Vesunna, future Périgueux, was created between 25 and 16 BC in a loop on the right bank of the Isle.[15] It benefited from Roman public power.[16] At that time, Vesunna was one of twenty-one cities in the province of Aquitaine.[17]

It was in the 1st century AD that the city, as a Roman town, underwent its greatest expansion, mainly in terms of urban planning, where the largest public monuments were built according to Roman plans, such as the forum, the amphitheatre and the thermae.[18] Throughout the 1st century, urban construction continued, not only enlarging existing buildings but also building more and more domus.[18] At the end of the 2nd century, following an invasion attributed to the Alemanni, the Roman city shrank to five and a half hectares,[19] retreating to a small plateau behind ramparts[20] built between 276 and 290.[6] Incorporating the north-western half of the Vesunna amphitheatre,[19] these walls were built using elements of the city's monuments (remnants of the ramparts remain), and this third city took the name Civitas Petrucoriorum ("city of the Petrocorii"),[15] the place that was to become "the Cité" (lit. french for "the town").[21] At the time, this enclosure comprised twenty-four towers, twenty-three curtain walls and four gates, of which only two remain today: the Porte Normande and the Porte de Mars.[19][22]

According to the geographer Strabo, the Petrocorii worked extensively with iron.[23]

At the beginning of the 5th century, the Visigoths ravaged Vesona, particularly its religious buildings, and settled on the site,[6] despite resistance organized in 407 by Pegasus, the occupant of the episcopal see.[24][25] Around 465, the king of the Visigoths, Euric, martyred the bishop and banned Catholic worship by closing down places of worship and suppressing the bishopric.[6] It was not until 506 that Bishop Chronope was able to restore worship and churches.[6]

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

Frankish domination by the Salians

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Franks came to dominate the region in the late 5th century. As a result, the Cité became Christian in the 6th century, even though the spread of religion had already reached a large part of urban society.[26]

During the reign of the Merovingians, the territory passed from hand to hand, provoking numerous disputes over the division of inheritance between the descendants of Clovis after his death in 511. Childebert I inherited first, until his death in 558, after which the lands of Charibert I in 561, then those of Guntram in 567, became part of the Vesone territory. With the help of the Church and the people of Vesone, Gontran defended the city against the violent attacks of his brother Chilperic I and Chlothar I's bastard son Gundoald.[26]

In 766, as a result of the conflict with Waiofar, the Duke of Aquitaine, Pepin the Short exercised his terror in Périgord, razing the city walls, including that of the ancient city of Petrocores[27].

Norman attacks and the emergence of Puy-Saint-Front

Between 840 and 865, the Normans made their way up the Isle, repeatedly pillaging and setting fire to the town.[28][29] Towards the end of the 10th century,[30] to the northeast and along the banks of the Isle, around a monastery that Bishop Frotaire (977-991) had built in honor of Saint Front, a new fortified center developed, known at the time as the "bourg du Puy-Saint-Front" (town of Puy-Saint-Front),[31] made up mainly of merchants, craftsmen and "laboureurs" (laborers).[32] To protect themselves from invaders, the two neighboring towns built walls.[19][30]

Central Middle Ages

The struggle between Church and nobility

Around 1040, Périgueux was troubled by unrest over the coinage minted by the Count of Périgord, Hélie II.[33] Shortly afterwards, the bishop Girard of Gourdon considered the coin to be defective and of poor quality, and banned it. Count Aldebert II, son of Hélie II, decided to prove, by force of arms, that it was suitable for him.[33][34] As a result, the town had to wage a long and bloody war against the Count.[34] The few dwellings under the protection of the new religious establishment of Puy-Saint-Front were burnt down around 1099; the convent and town were soon rebuilt.[31]

Pilgrims flocked to the site of Saint Front's relics.[35] In the 11th century, the number of houses increased and the settlement grew ever larger.[31] Over time, however, the town's inhabitants became increasingly divided. Around 1104, the burghers and citizens of the two neighboring communes came to blows; in the midst of this struggle, the burghers murdered Pierre de Périgueux, a descendant of a very old family of the Cité, and threw him into the Isle river.[36] Around 1130, in a quarrel with the convent, some of the burghers of Puy-Saint-Front allied themselves with Count Hélie-Rudel.[37] He was convinced that, having conquered Puy-Saint-Front, it would be easier for him to finally subdue the Cité, something none of his ancestors had managed to do.[37] At the same time, the counts dominated Puy-Saint-Front.[37]

Loyalty to the throne of England or the king of France?

Around 1150, Boson III, known as de Grignols, had a large, fortified tower built to command and watch over the Cité, which he had just seized.[38] But this attempt at oppression proved fatal for him and his descendants, as it aroused the anger of King Henry II of England, who had become Duke of Aquitaine by marriage.[38] The tower was destroyed in 1182, when, following a treaty with Count Helie V, Puy-Saint-Front fell into the hands of Henry II's son, Richard, who had all the fortifications built by him and his predecessor demolished.[38] At the same time, at the end of the 11th century, the "bourg du Puy-Saint-Front" (town of Puy-Saint-Front) was organized as a municipality.[39]

Having confiscated the Duchy of Aquitaine from John Lackland and reunited it with the crown of France, Philip Augustus demanded that the peoples and lords of this duchy pay him homage. In 1204, Hélie V and the inhabitants of the future city of Périgueux swore loyalty to the French monarch.[40]

Background to the treaty of alliance and the founding of Périgueux

For many years, Puy-Saint-Front and the counts lived in harmony.[41] The town's municipal organization had long been recognized and established by royal authority.[41] As for the Cité, it encountered no difficulties with the counts.[41] A first agreement between the two urban centers was established in 1217.[6] The state of peace lasted until 1239, and there was even a degree of trust between Count Archambaud II and the town. At that time, the latter paid him 50 pounds in exchange for relinquishing the annual rent of 20 pounds it owed him each Christmas.[41]

To ensure mutual protection and assistance, and to put an end to rivalries, Périgueux was founded in 1240 as a result of a treaty to unite[42] the two towns located just a few hundred meters apart:[43] the Cité - derived from the Gallo-Roman Vésone - the town of the bishop and the Count of Périgord,[21] and the middle-class town of Puy-Saint-Front.[30]

Renewed noble conflicts in Périgord

Hostilities between the Counts of Périgord and the new town lasted until 1250, when Bishop Pierre III de Saint-Astier[44] put an end to the discord. In the 13th century, new bourgeois settled in Périgueux to increase their land holdings by buying up vacant plots, while taking advantage of the privileged relationships they maintained with their parishes of origin, where they still kept properties.[45] Returning to the region of their ancestors, cloth merchants also settled in Périgueux, acquiring numerous rents and lands in a wide radius around the city.[45] Count Archambaud III had further disputes with Périgueux: in 1266, over the manufacture of coins, and in 1276 over their value.[44] This power struggle continued from generation to generation.[46] In principle, the counts claimed sovereign power, claiming to be the sole owners of the town of Puy-Saint-Front from the seventeenth century, then seeking royal favor in the fourteenth century.[46] These long conflicts came to an end in the 14th century, when the Count of Périgord, Roger-Bernard, son of Archambaud IV,[47] became the vassal of the English, who confirmed the possessions and jurisdiction[48] of the bourgeois of Périgueux (" Mayors, Consuls & Citizens of the City "), and Charles VI sent troops to their aid, after the bourgeois had been appealing to the royal justice system for more than eight years.[49]

Late Middle Ages

On April 16, 1321, a large number of lepers from the surrounding area were interned in Périgueux, then tortured before being either burned (the men) or walled up alive (the women).[50] In 1347, a flood on the Isle swept away part of the walls of Puy-Saint-Front.[51] From the middle of the 14th century, the countryside around Périgueux went through a period of serious crisis, marked in particular by a sharp fall in population due to the devastating effects of the Black Death and the Hundred Years' War.[52] During the Hundred Years' War, Périgueux remained loyal to the Kingdom of France, even when it was occupied by the English between 1360 and 1363.[53] In those years, the people of Périgueux submitted to the authority of Edward of Woodstock, nicknamed the Black Prince, who effectively levied the "fouage" (hearth tax) to feed the coffers of the principality of Aquitaine;[54] in 1367 alone, the town faced three tailles and five hearth taxes.[55] During this period, the counts and their descendants, most of whom lived in their castle at Montignac, pledged their allegiance to the kingdom of England. Charles VI confiscated their lands and titles in favour of his brother Louis d'Orléans. By transfer or marriage to the Orleans family, Périgord passed into the hands of the House of Châtillon in 1437, then into the House of Albret in 1481.

The shortage of manpower led to a contraction in cultivated land, with "deserts"[56] appearing at the very heart of the vineyards in the parish of Saint-Martin. In the 15th century, the town's activity picked up again and was dominated by merchants, as illustrated by the construction of Hôtels particuliers.[1]

Modern times

In May 1472, King Louis XI confirmed the town's privileges in his letters patent, following the death of his brother Charles, Duke of Guyenne.[57]

In 1524, the town suffered a terrible plague epidemic.[58] In 1530, the town's consuls decided to build a college. To this end, on 7 October 1531, the mayor and consuls bought the house of Pierre Dupuy. The college was mentioned in 1574 in François de Belleforest's Cosmographie universelle de tout le monde.[59] Jesuits expelled from Bordeaux arrived in Périgueux in July 1589. An agreement was signed on 23 December 1591 between the city authorities and Father Clément, provincial of the Jesuits. On 23 April 1592, Claudio Acquaviva, General of the Jesuits, approved an agreement concerning the new house of education entrusted to the Jesuits. The college was founded a second time on 9 October 1592.[60]

Taxes continued to rise, in particular the gabelle, which became unbearable for the inhabitants of Périgueux, so much so that they revolted in 1545.[61]

The Wars of Religion were more deadly for Périgueux than the Hundred Years' War. Périgueux was taken on 6 August 1575 by Calvinists[62][28] under the command of Favas and Guy of Montferrand, then pillaged and occupied.[63] Their strategy was to enter the town with soldiers disguised as peasants.[64] That same year, in Puy Saint-Front, the shrine and reliquary containing the remains of the holy bishop were stolen and taken to Château de Tiregand, where the saint's bones were thrown into the Dordogne.[63] Périgueux remained in Protestant hands for six years, until 1581,[6] when Captain Belsunce, governor of the town, allowed it to be taken by the Catholic Jean de Chilhaud. Périgord became part of the French crown in 1589, when its last Count, the son of Jeanne d'Albret, became King of France under the name of Henri IV.

In the seventeenth century, during the reign of Louis XIII, the town was on the border of a region that was subject to rebellion, extending as far south as the territory that is now the Dordogne department.[65] In 1636, during the Croquant rebellions, Périgueux was the scene of peasant revolts, but was not one of the towns or castles, such as Grignols, Excideuil and then Bergerac, that were taken by peasants during this period.[65] Their aim was to bring 6,000 men into Périgueux, steal the cannons and pursue the gabeleurs. On 1 May, the town was repatriated behind its ramparts and resisted the attackers. The large peasant army guarded the town day and night and stayed around the fortifications for three weeks, barricading the bridge to prevent the arrival of the troops of Jean Louis de Nogaret de La Valette, Duke of Épernon, commanded by his son Bernard de Nogaret de La Valette. La-Mothe-La-Forêt, the obscure gentleman who led this army of "communes", was finally victorious when the consensus declared a peasant payroll.[66]

In October 1651, during the Fronde, Périgueux welcomed the troops of the Prince of Condé.[67] In August 1653, during the Lorraine War, it was the only town in the south-west to remain hostile to the King, a situation that lasted until the following 16 September, when its inhabitants threw out the rebels.[67] In gratitude, the town's magistrates officially granted their wishes, leading to a pilgrimage to Notre-Dame-des-Vertus.[68] In 1669, the cathedral was moved from the ruined Saint-Étienne-de-la-Cité to Saint-Front cathedral, the former church of the abbey of the same name.[69] In autumn 1698, the misery of recent years had become unbearable, prompting the bishop of Périgueux to appeal to "the King's kindness".[70]

On 5 and 6 March 1783, the town experienced one of the highest floods of the Isle. The water rose to 5.21 metres, the highest level ever recorded for Périgueux,[71] drowning the causeway of the Pont Saint-Georges.[51] In 1789, the clergy, nobility and third estate came from all over the province to elect their deputies to the Estates-General. After the creation of the départements in 1790, the departmental assembly met alternately in Bergerac, Périgueux and Sarlat. Périgueux became the official capital of the Dordogne in September 1791.[72]

Contemporary times

19th century

From the First Empire to the July Monarchy

The Napoleonic Wars mobilised many young people in Périgueux. The wars also provided an opportunity for a number of prominent figures to shine, including General Pierre Daumesnil, Marquis Antoine Pierre Joseph Chapelle and Marshal Thomas-Robert Bugeaud. This mobilisation and requisitioning led to an increase in taxes. Most of the conscripts from Périgord died on the battlefield and the few men who returned were permanently wounded. As a result, numerous protests took place in front of the Dordogne prefecture.[73]

Under the First Empire, the town, seat of the prefecture,[74] was enlarged in 1813 by merging with the former commune of Saint-Martin.[75]

In 1815, the deputies from the Périgord were mostly in the ranks of the Ultras, facing the small number of liberal monarchists elected from 1824 onwards: the Dordogne was thus more in opposition to the ministry of Joseph de Villèle. At the end of the 1820s, they supported the Jean-Baptiste de Martignac ministry and then opposed that of Jules de Polignac.[76] In December 1836, a major flood of the river Isle swept away the dam at the Saint-Front mill by around twenty metres (70 to 80 feet), and on January 15 1843, the river reached a level comparable to the record flood of 1783.[51]

Second Republic

In the presidential election of 1848, the people of Périgueux voted overwhelmingly for Napoleon III (88.5% of the votes cast). [Note 1]After the coup d'état of 1851, the proclamation of the Second Empire on December 2 was widely approved in Périgueux; 78% of the population of the département said "yes" in 1851 and 78.3% in 1852. The people of Périgueux remained strongly attached to the Bonapartist regime, always electing the candidates officially declared by the Emperor.[Note 2] In the plebiscite of May 8 1870, 77.7% of registered voters in the Dordogne approved the liberalisation of the regime.[77]

Belle Époque

Following the merger of Saint-Martin and Périgueux in 1813,[78] the town's population doubled in around forty years (13,547 inhabitants were recorded in 1851).[79] The town was boosted by advances in river and road transport. The fact that Périgueux had been chosen as a prefecture led to an increase in the number of civil servants, professionals, trades and public services. In terms of economic growth, Périgueux overtook Bergerac, until then the leading town in Périgord.[80] However, its main economic activity remained agriculture until the 20th century.[81]

In 1857, Périgueux saw the arrival of the railway from Coutras[82] and, from 1862, the installation of repair workshops for the locomotives and carriages of the Compagnie du Paris-Orléans.[83] This activity still survives in the Toulon district at the beginning of the 21st century. The Périgueux-Coutras line was supplemented by links to Brive-la-Gaillarde in 1860, Limoges in 1862 and Agen in 1863, making it the town in the Dordogne with the most rail connections.[84] It was also in the 19th century that two architects worked in Périgueux. Louis Catoire built the Courthouse, the Coderc covered market and the Theatre - which has now disappeared - as well as various buildings on Place Bugeaud.[85] Paul Abadie restored Saint-Front cathedral.[86]

Périgueux became increasingly depopulated between 1866 and 1911, as the people of the region were drawn to metropolis such as Bordeaux and Paris. This led to a decline in the local population, taking into account the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and the low birth rate, which was exceeded by the death rate. Nevertheless, the population grew, balanced by high emigration.[87]

From the 1880s onwards, Périgueux experienced a decline in the old iron and steel industry, supported by the wine crisis. Industrial productivity collapsed, but the modern systems of the second industrial revolution were unable to offset this deficit.[88]

References

- ^ a b Delattre, Daniel; et al. (May 2009). La Dordogne, les 557 communes (in French). Grandvilliers: Éditions Delattre. p. 140-142. ISBN 978-2-915907-50-6..

- ^ Cocula 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 416.

- ^ Cocula 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Célerier, G. (1967). "Le gisement périgordien supérieur des "Jambes", commune de Périgueux (Dordogne)" (in persee). Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French). 64 (1): 53–68..

- ^ a b c d e f g Penaud 2003, pp. 113–117.

- ^ Les Celtes, histoire et dictionnaire (in French). Paris: Robert Laffont. 2000. p. 776..

- ^ Chevillot, Claude (February 10, 2016). "Coulounieix-Chamiers – Écorneboeuf". ADLFI. Archéologie de la France - Informations (in French)..

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Colin, Anne (2007). "État des recherches récentes sur l'oppidum du camp de César (ou de La Curade), Coulounieix-Chamiers (Dordogne)". Aquitania (in French). 14. Bordeaux: 227–236. ISSN 2015-9749..

- ^ Wlgrin de Taillefer, Antiquités de Vésone, cité gauloise, remplacée par la ville actuelle de Périgueux (in French), tome 1, Périgueux, 1821, pp. 121-122 (read online)

- ^ Jules César, Commentaires sur la Guerre des Gaules (in French), livre I, 1.

- ^ Aubarbier, Jean-Luc; Binet, Michel; Mandon, Guy (1987). Nouveau guide du Périgord-Quercy (in French). Rennes: Ouest-France. p. 22-23. ISBN 2-85882-842-3..

- ^ "Noms antiques des villes & peuples de l'Aquitaine". Lexilogos (in French). Retrieved September 22, 2012..

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 573–574.

- ^ Moreau 1775, p. 20.

- ^ Cocula 2011, p. 29.

- ^ a b Lachaise 2000, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Penaud 2003, p. 122-123.

- ^ "Petit tour d'horizon de la Ville". le site de la mairie de Périgueux. 28 January 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2012..

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 103.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 94.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 108.

- ^ Penaud, Guy (December 1999). Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord (in French). Périgueux: Fanlac editions. p. 732. ISBN 2-86577-214-4..

- ^ a b Lachaise 2000, p. 112.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 113.

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 369–370.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Penaud 2003, pp. 424–426.

- ^ a b c Dessalles 1847, p. 8.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 143.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 6.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 7.

- ^ Aubarbier, Jean-Luc; Binet, Michel; Mandon, Guy (1987). Nouveau guide du Périgord-Quercy (in French). Rennes: Ouest-France. p. 39. ISBN 2-85882-842-3..

- ^ Penaud, Guy (December 1999). Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord (in French). Périgueux: Fanlac editions. p. 736. ISBN 2-86577-214-4..

- ^ a b c Dessalles 1847, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Dessalles 1847, p. 10.

- ^ Penaud 2003, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Dessalles 1847, p. 12.

- ^ « Traité de réunion de la Cité et de la ville de Périgueux (année 1240) », dans Le chroniqueur du Périgord et du Limousin (in French), 1854, pp. 45-47 (read online)

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 13.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 15.

- ^ a b Marty 1993, p. 71.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 55.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 56.

- ^ Maur Dantine, Clément (1784). L'Art de vérifier les dates des faits historiques, des chartes, des chroniques et autres ancien monumens, depuis la naissance de Notre-Seigneur (in French). Paris: Alexandre Jombert. p. 384..

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 178.

- ^ Penaud 2003, pp. 291–292.

- ^ a b c Penaud 2003, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 71.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 75.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 169.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 170.

- ^ Marty 1993, p. 76.

- ^ Lettres patentes de Louis XI, Saintes, mai 1472 in Eusèbe de Laurière, Ordonnances des Rois de France de la troisièmme Race (in French), recueillies par ordre chronologique, imprimerie royale, 1820, p. 497 (read online).

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 200.

- ^ de Belleforest, François, Cosmographie universelle de tout le monde (in French), in Michel Sonnius, Paris, 1575, (lire en ligne)

- ^ Lambert, Ch., « Le Collège de Périgueux, des origines à 1792 » (in French), dans Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du Périgord, 1927, tome 54, pp. 72-85 (read online)

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 201.

- ^ "Archive Larousse : Grande Encyclopédie Larousse - Périgueux". le site des éditions Larousse (in French). Retrieved September 22, 2012..

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 223–226.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 210.

- ^ a b Marty 1993, p. 105.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, p. 222.

- ^ "Pèlerinage de Notre-Dame de Sanilhac". PERIZOOM (in French) (96): 6. September 2013..

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 465.

- ^ Marty 1993, p. 121.

- ^ Mankowski, Thomas, Le jour où l'Isle a noyé la ville (in French), Sud Ouest édition Périgueux of December 31, 2014, pp. 12-13.

- ^ Préfecture de la Dordogne. "Le cadre administratif : de la province à la région" (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2012..

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Penaud 2003, pp. 412–414.

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 491.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 257-259.

- ^ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet {{{1}}}, EHESS (in French).

- ^ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet {{{1}}}, EHESS (in French).

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 250.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 260.

- ^ "L'aventure du rail" (pdf). le site de la mairie de Périgueux. Périgueux le magazine des Périgourdins, No. 9. Template:4e trimestre 2010. p. 34. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|en ligne le=ignored (|archive-date=suggested) (help). - ^ Penaud 2003, p. 50-51.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 259.

- ^ Penaud, Guy (December 1999). Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord (in French). Périgueux: éditions Fanlac. p. 204. ISBN 2-86577-214-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|pages totales=ignored (help). - ^ Laroche, Claude. Saint-Front de Périgueux: la restauration au 19th century. p. 267-280., dans Congrès archéologique de France: Template:156e session - Monuments en Périgord - 1999. Paris: Société Française d'Archéologie. 1999..

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 261-262.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 263.

Cite error: There are <ref group=Note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=Note}} template (see the help page).