Book of Abraham: Difference between revisions

m →Translation process: copy edit |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Add: pages. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | #UCB_webform 11/207 |

||

| Line 442: | Line 442: | ||

| issue=4 |

| issue=4 |

||

| date=December 2000 |

| date=December 2000 |

||

| pages=97–119 |

|||

| doi=10.2307/45226742 |

| doi=10.2307/45226742 |

||

| jstor=45226742 |

| jstor=45226742 |

||

Revision as of 05:59, 25 September 2023

The Book of Abraham is a collection of writings claimed to be from several Egyptian scrolls discovered in the early 19th century during an archeological expedition by Antonio Lebolo. Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) purchased the scrolls from a traveling mummy exhibition on July 3, 1835, to be translated into English by Joseph Smith.[1] According to Smith, the book was "a translation of some ancient records... purporting to be the writings of Abraham, while he was in Egypt, called the Book of Abraham, written by his own hand, upon papyrus".[2] Smith said the papyri described Abraham's early life, his travels to Canaan and Egypt, and his vision of the cosmos and its creation.

The Latter-day Saints believe the work is divinely inspired scripture, published as part of the Pearl of Great Price since 1880. It thus forms a doctrinal foundation for the LDS Church and Mormon fundamentalist denominations, though other groups, such as the Community of Christ, do not consider it a sacred text. The book contains several doctrines that are unique to Mormonism such as the idea that God organized eternal elements to create the universe (instead of creating it ex nihilo), the potential exaltation of humanity, a pre-mortal existence, the first and second estates, and the plurality of gods.

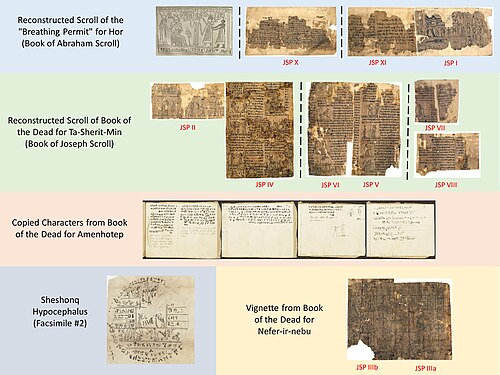

The Book of Abraham papyri were thought to have been lost in the 1871 Great Chicago Fire. However, in 1966 several fragments of the papyri were found in the archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and in the LDS Church archives. They are now referred to as the Joseph Smith Papyri. Upon examination by professional Egyptologists (both Mormon and otherwise), these fragments were identified as Egyptian funerary texts, including the "Breathing Permit of Hôr"[nb 1] and the "Book of the Dead", among others. Although some Mormon apologists defend the authenticity of the Book of Abraham, no other scholars regard it as an ancient text.[3]

Origin

Eleven mummies and several papyri were discovered near the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes by Antonio Lebolo between 1818 and 1822. Following Lebolo's death in 1830, the mummies and assorted objects were sent to New York with instructions that they should be sold in order to benefit the heirs of Lebolo.[4] Michael H. Chandler eventually came into possession of the mummies and artifacts and began displaying them, starting in Philadelphia.[5] Over the next two years Chandler toured the eastern United States, displaying and selling some of the mummies as he traveled.[6][7]

In late June or early July 1835, Chandler exhibited his collection in Kirtland, Ohio. A promotional flyer created by Chandler states that the mummies "may have lived in the days of Jacob, Moses, or David".[8] At the time, Kirtland was the home of the Latter Day Saints, led by Joseph Smith. In 1830 Smith published the Book of Mormon which he said he translated from ancient golden plates that had been inscribed with "reformed Egyptian" text. He took an immediate interest in the papyri and soon offered Chandler a preliminary translation of the scrolls.[9] Smith said that the scrolls contained the writings of Abraham and Joseph, as well as a short history of an Egyptian princess named "Katumin".[10] He wrote:

[W]ith W. W. Phelps and Oliver Cowdery as scribes, I commenced the translation of some of the characters or hieroglyphics, and much to our joy found that one of the [scrolls] contained the writings of Abraham, another the writings of Joseph of Egypt, etc. – a more full account of which will appear in its place, as I proceed to examine or unfold them.[7]

Smith, Joseph Coe, and Simeon Andrews soon purchased the four mummies and at least five papyrus documents for $2,400 (equivalent to $71,000 in 2023).[9][11]

| Egyptian Document | Text Description | Joseph Smith Description | Joseph Smith Papyri Number | Date Created |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Hor Book of Breathing" | Funerary scroll made for a Theban Priest name Horus (also Horos, Hor). It is among the earliest known copies of the Book of Breathing. Sometimes referred to as a Breathing Permit or Sensen text | "Book of Abraham" | I, torn fragments pasted into IV, X, XI and Facsimile #3 | between 238-153 BC |

| "Ta-sherit-Min Book of the Dead" | Funerary scroll made for Ta-sherit-Min (also Tshemmin, Semminis) | "Book of Joseph" | II, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII | circa 300-100 BC |

| "Nefer-ir-nebu Book of the Dead" Judgement Scene | Funerary papyrus scroll fragment made for Nefer-ir-nebu (also Neferirtnub, Noufianoub) showing a vignette with the deceased standing before Osiris, waiting to have her heart weighed on a balance against a feather, to determine if she is worthy of further existence, or having her soul devoured by Ammit | No known description given by Joseph Smith. | III a,b | circa 300-100 BC |

| "Amenhotep Book of the Dead" | Fragment from a funerary scroll made for Amenhotep (also Amen-ophis) | Parts were translated as a short history of a Princess Katumin, daughter of Pharaoh Onitas | The papyrus is no longer extant. Characters were copied into a notebook (see Kirtland Egyptian Papers). | Unknown |

| Sheshonq Hypocephalus | A funerary text placed under the head of the deceased named Sheshonq (also Shashaq, Sesonchis) | Facsimile #2 from the "Book of Abraham" | The papyrus is no longer extant. | Unknown |

Translation process

Ancient Egyptian writing systems had been a subject of fascination for centuries, drawing the attention of scholars who attempted to understand the symbols. The Rosetta Stone, an ancient monument discovered in 1799, had the same message written in ancient Egyptian and the Greek alphabet, allowing for the first comprehensive understanding of ancient Egyptian in modern times. However, at the time Smith began his efforts the Rosetta Stone was not fully understood. Not until the 1850s would there be a wide scholarly consensus on how to translate ancient Egyptian writing.

Between July and November 1835 Smith began "translating an alphabet to the Book of Abraham, and arranging a grammar of the Egyptian language as practiced by the ancients."[13] In so doing, Smith worked closely with Cowdery and Phelps.[14][15] The result of this effort was a collection of documents and manuscripts now known as the Kirtland Egyptian papers. One of these manuscripts was a bound book titled simply "Grammar & A[l]phabet of the Egyptian Language", which contained Smith's interpretations of the Egyptian glyphs.[15][16] The first part of the book focuses almost entirely on deciphering Egyptian characters, and the second part deals with a form of astronomy that was supposedly practiced by the ancient Egyptians.[17] Most of the writing in the book was written not by Smith but rather by a scribe taking down what Smith said.[15]

The "Egyptian Alphabet" manuscript is particularly important because it illustrates how Smith attempted to translate the papyri. First, the characters on the papyri were transcribed onto the left-hand side of the book. Next, a postulation as to what the symbols sounded like was devised. Finally, an English interpretation of the symbol was provided. Smith's subsequent translation of the papyri takes on the form of five "degrees" of interpretation, each degree representing a deeper and more complex level of interpretation.[17]

In translating the book, Smith dictated, and Phelps, Warren Parrish, and Frederick G. Williams acted as scribes.[18] The complete work was first published serially in the Latter Day Saint movement newspaper Times and Seasons in 1842,[nb 2] and was later canonized in 1880 by the LDS Church as part of its Pearl of Great Price.[1]

Eyewitness accounts of how the Papyri were translated are few and vague. Warren Parish, who was Joseph Smith's scribe at the time of the translation, wrote in 1838 after he had left the church: "I have set by his side and penned down the translation of the Egyptian Hieroglyphicks [sic] as he claimed to receive it by direct inspiration from Heaven."[20] Wilford Woodruff and Parley P. Pratt intimated second hand that the Urim and Thummim were used in the translation.[21][22]

A non-church member who saw the mummies in Kirtland spoke about the state of the papyri, and the translation process:

"These records were torn by being taken from the roll of embalming salve which contained them, and some parts entirely lost but Smith is to translate the whole by divine inspiration, and that which was lost, like Nebuchadnezzar's dream can be interpreted as well as that which is preserved;"[23]

Content

Book of Abraham text

The Book of Abraham tells a story of Abraham's life, travels to Canaan and Egypt, and a vision he received concerning the universe, a pre-mortal existence, and the creation of the world.[24] Although the nineteenth-century American context surrounding Smith's papyri translation was rife with Egyptomania,[25] the Book of Abraham itself does not contain the popular tropes then associated with ancient Egypt, such as mummies or pyramids,[26] and its content instead "grew out of the Bible."[27]

The book has five chapters, outlined below:

| Chapter | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Recounts how Abraham's father Terah and his forefathers had turned to "the god of Elkenah, and the god of Libnah, and the god of Mahmackrah, and the god of Korash, and the god of Pharaoh, king of Egypt".[28][29] Chaldean priests then sacrifice three virgins to pagan gods of stone and wood, and one priest attempts to sacrifice Abraham himself before an angel comes to his rescue.[30][31] The text then examines the origins of Egypt and its government.[24][32] |

| 2 | Includes information about God's covenant with Abraham and how it would be fulfilled; in this chapter, Abraham travels from Ur to Canaan, and then to Egypt.[24][33] |

| 3 | Abraham learns about an Egyptian understanding of celestial objects via the Urim and Thummim.[24][34] It is in this chapter that Abraham also learns about the "eternal nature of spirits [...] pre-earth life, foreordination, the Creation, the choosing of a Redeemer, and the second estate of man."[24] |

| 4 | Along with chapter 5, contains expansions and modifications of the creation narrative in Genesis.[35] The gods (there are over 48 references to the plurality of the gods in Chapters 4 and 5[36]) plan the creation of the earth and life on the earth. |

| 5 | The gods complete creation, and Adam names all living creatures.[24] |

Nearly half of the Book of Abraham shows a dependence on the King James Version of the Book of Genesis.[37] According to H. Michael Marquardt, "It seems clear that Smith had the Bible open to Genesis as he dictated this section [i.e., Chapter 2] of the 'Book of Abraham.'"[38] Smith explained the similarities by reasoning that when Moses penned Genesis, he used the Book of Abraham as a guide, abridging and condensing where he saw fit. As such, since Moses was recalling Abraham's lifetime, his version was in the third person, whereas the Book of Abraham, being written by its titular author, was composed in the first person.[38][39]

The Book of Abraham was incomplete when Joseph Smith died in 1844.[40] It is unknown how long the text would be, but Oliver Cowdery gave an indication in 1835 that it could be quite large:

When the translation of these valuable documents will be completed, I am unable to say; neither can I gave you a probable idea how large volumes they will make; but judging from their size, and the comprehensiveness of the language, one might reasonably expect to see sufficient to develop much on the mighty of the ancient men of God.[41]

A visitor to Kirtland saw the mummies, and noted, "They say that the mummies were Epyptian, but the records are those of Abraham and Joseph...and a larger volume than the Bible will be required to contain them."[42]

Distinct doctrines

The Book of Abraham text is a source of some distinct Latter Day Saint doctrines, which Mormon author Randal S. Chase calls "truths of the gospel of Jesus Christ that were previously unknown to Church members of Joseph Smith's day."[43] Examples include the nature of the priesthood,[44] an understanding of the cosmos,[45] the exaltation of humanity,[46] a pre-mortal existence, the first and second estates,[47] and the plurality of gods.[48]

The Book of Abraham expands upon the nature of the priesthood in the Latter Day Saint movement, and it is suggested in the work that those who are foreordained to the priesthood earned this right by valor or nobility in the pre-mortal life.[49] In a similar vein, the Book explicitly denotes that Pharaoh was a descendant of Ham[50] and thus "of that lineage by which he could not have the right of Priesthood".[51] This passage is the only one found in any Mormon scripture that bars a particular lineage of people from holding the priesthood. Even though nothing in the Book of Abraham explicitly connects the line of Pharaoh and Ham to black Africans,[52] this passage was used as a scriptural basis for withholding the priesthood from black individuals.[53] An 1868 Juvenile Instructor article points to the Pearl of Great Price as the "source of racial attitudes in church doctrine",[54] and in 1900, First Presidency member George Q. Cannon began using the story of Pharaoh as a scriptural basis for the ban.[55]: 205 In 1912, the First Presidency responded to an inquiry about the priesthood ban by using the story of Pharaoh.[56] By the early 1900s, it became the foundation of church policy in regards to the priesthood ban.[55]: 205 The 2002 Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual points to Abraham 1:21–27 as the reasoning behind not giving black people the priesthood until 1978.[57]

Chapter 3 of the Book of Abraham describes a unique (and purportedly Egyptian[34][58]) understanding of the hierarchy of heavenly bodies, each with different movements and measurements of time.[59] In regard to this chapter, Randal S. Chase notes, "With divine help, Abraham was able to gain greater comprehension of the order of the galaxies, stars, and planets than he could have obtained from earthly sources."[34] At the pinnacle of the cosmos is the slowest-rotating body, Kolob, which, according to the text, is the star closest to where God lives.[60] The Book of Abraham is the only work in the Latter Day Saint canon to mention the star Kolob.[61] According to the Book:

[Abraham] saw the stars, that they were very great, and that one of them was nearest unto the throne of God; ... and the name of the great one is Kolob, because it is near unto me, for I am the Lord thy God: I have set this one to govern all those which belong to the same order as that upon which thou standest.[62]

Based on this verse, the LDS Church claims that "Kolob is the star nearest to the presence of God [and] the governing star in all the universe."[63] Time moves slowly on the celestial body; one Kolob-day corresponds to 1,000 earth-years.[59] The Church also notes: "Kolob is also symbolic of Jesus Christ, the central figure in God's plan of salvation."[63]

The Book of Abraham also explores pre-mortal existence. The LDS Church website explains: "Life did not begin at birth, as is commonly believed. Prior to coming to earth, individuals existed as spirits."[64] These spirits are eternal and of different intelligences.[65] Prior to mortal existence, spirits exist in the "first estate". Once certain spirits (i.e., those who choose to follow the plan of salvation offered by God the Father of their own accord) take on a mortal form, they enter into what is called the "second estate".[63][66] The doctrine of the second estate is explicitly named only in this book.[67] The purpose of earthly life, therefore, is for humans to prepare for a meeting with God; the Church, citing Abraham 3:26 notes: "All who accept and obey the saving principles and ordinances of the gospel of Jesus Christ will receive eternal life, the greatest gift of God, and will have 'glory added upon their heads for ever and ever'."[63][64]

Also notable is the Book of Abraham's description of a plurality of gods, and that "the gods"[nb 3] created the Earth, not ex nihilo, but rather from pre-existing, eternal matter.[64][36] This shift away from monotheism and towards henotheism occurred c. 1838–39, when Smith was imprisoned in the Liberty Jail in Clay County, Missouri (this was after the majority of the Book of Abraham had been supposedly translated, but prior to its publication).[69] Smith noted that there would be "a time come in the [sic] which nothing shall be with held [sic] whither [sic] there be one god or many gods they [sic] shall be manifest all thrones and dominions, principalities and powers shall be revealed and set forth upon all who have indured [sic] valiently [sic] for the gospel of Jesus Christ" and that all will be revealed "according to that which was ordained in the midst of the councyl [sic] of the eternal God of all other Gods before this world was."[70]

Facsimiles

Three images (facsimiles of vignettes on the papyri) and Joseph Smith's explanations of them were printed in the 1842 issues of the Times and Seasons.[71] These three illustrations were prepared by Smith and an engraver named Reuben Hedlock.[72] The facsimiles and their respective explanations were later included with the text of the Pearl of Great Price in a re-engraved format.[73] According to Smith's explanations, Facsimile No. 1 portrays Abraham fastened to an altar, with the idolatrous priest of Elkenah attempting to sacrifice him.[74] Facsimile No. 2 contains representations of celestial objects, including the heavens and earth, fifteen other planets or stars, the sun and moon, the number 1,000 and God revealing the grand key-words of the holy priesthood.[75] Facsimile No. 3 portrays Abraham in the court of Pharaoh "reasoning upon the principles of Astronomy".[76]

-

Facsimile No. 1 from the Book of Abraham

-

Facsimile No. 2 from the Book of Abraham

-

Facsimile No. 3 from the Book of Abraham

Interpretations and contributions to the LDS movement

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Book of Abraham was canonized in 1880 by the LDS Church, and it remains a part of the larger scriptural work, the Pearl of Great Price.[64][26] For Latter-day Saints, the book links Old and New Testament covenants into a universal narrative of Christian salvation, expands on premortal existence, depicts ex materia cosmology, and informed Smith's developing understanding of temple theology, making the scripture "critical to understanding the totality of his gospel conception".[77]

Church leadership traditionally described the Book of Abraham straightforwardly as "translated by the Prophet [Joseph Smith] from a papyrus record taken from the catacombs of Egypt",[78] and "Some have assumed that hieroglyphs adjacent to and surrounding facsimile 1 must be a source for the text of the book of Abraham".[64] However, modern Egyptological translations of papyrus fragments reveal the surviving Egyptian text matches the Breathing Permit of Hôr, an Egyptian funerary text, and does not mention Abraham. The church acknowledges this,[79] and its members have adopted a range of interpretations of the Book of Abraham to accommodate the seeming disconnect between the surviving papyrus and Smith's Book of Abraham revelation.[64][80] The two most common interpretations are sometimes called the "missing scroll theory" and the "catalyst theory", though the relative popularity of these theories among Latter-day Saints is unclear.[26][54]

The "missing scroll theory" holds that Smith may have translated the Book of Abraham from a now-lost portion of papyri, with the text of Breathing Permit of Hôr having nothing to do with Smith's translation.[80][64] John Gee, an Egyptologist and Latter-day Saint, and the apologetic organization FAIR (Faithful Answers, Informed Response; formerly FairMormon) favor this view.[81][82]

Other Latter-day Saints hold to the "catalyst theory," which hypothesizes that Smith's "study of the papyri may have led to a revelation about key events and teachings in the life of Abraham", allowing him to "translate" the Book of Abraham from the Breathing Permit of Hôr papyrus by inspiration without actually relying on the papyrus' textual meaning.[64][83] This theory draws theological basis from Smith's "New Translation" of the Bible, wherein in the course of rereading the first few chapters of Genesis, he dictated as a revelatory translation the much longer Book of Moses.[64][84]

FAIR has claimed the church "favors the missing scroll theory".[81] However, in 2019, the Joseph Smith Papers' documentary research on the Book of Abraham and Egyptian papyri makes it "clear that Joseph Smith and/or his clerks associated the characters from the [surviving Breathing Permit of Hôr] papyri with the English Book of Abraham text", seeming to give more credence to the catalyst theory.[according to whom?][85]

Community of Christ

The Community of Christ, formerly known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, does not include the Book of Abraham in its scriptural canon, although it was referenced in early church publications.[86][nb 4]

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite)

The Strangite branch of the movement does not take an official position on the Book of Abraham. The branch notes, "We know that 'The Book of Abraham' was published in an early periodical as a text 'purporting to be the writings of Abraham' with no indication of its translation process (see Times and Seasons, March 1, 1842), and therefore have no authorized position on it."[88]

Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

The Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints holds to the canonicity of the Book of Abraham.[89]

Loss and rediscovery of the papyrus

After Joseph Smith's death, the Egyptian artifacts were in the possession of his mother, Lucy Mack Smith, and she and her son William Smith continued to exhibit the four mummies and associated papyri to visitors.[73] Two weeks after Lucy's death in May 1856, Smith's widow, Emma Hale Smith Bidamon, her second husband Lewis C. Bidamon,[nb 5] and her son Joseph Smith III, sold "four Egyptian mummies with the records with them" to Abel Combs on May 26, 1856.[73][91][92] Combs later sold two of the mummies, along with some papyri, to the St. Louis Museum in 1856.[90] Upon the closing of the St. Louis Museum, these artifacts were purchased by Joseph H. Wood and found their way to the Chicago Museum in about 1863, and were promptly put on display.[93] The museum and all its contents were burned in 1871 during the Great Chicago Fire. Today it is presumed that the papyri that formed the basis for Facsimiles 2 and 3 were lost in the conflagration.[90][94]

After the fire, however, it was believed that all the sources for the book had been lost.[95] Despite this belief, Abel Combs still owned several papyri fragments and two mummies. While the fate of the mummies is unknown, the fragments were passed to Combs' nurse Charlotte Benecke Weaver, who gave them to her daughter, Alice Heusser. In 1918 Heusser approached the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) about purchasing the items; at the time, the museum curators were not interested, but in 1947 they changed their mind, and the museum bought the papyri from Heusser's widower husband, Edward. In the 1960s the MMA decided to raise money by selling some of its items which were considered "less unique". Among these were the papyri that Heusser had sold to the museum several decades earlier.[96] In May 1966, Aziz S. Atiya, a Coptic scholar from the University of Utah, was looking through the MMA's collection when he came across the Heusser fragments; upon examining them, he recognized one as the vignette known as Facsmile 1 from The Pearl of Great Price.[96][97] He informed LDS Church leaders, and several months later, on November 27, 1967, the LDS Church was able to procure the fragments,[96] and according to Henry G. Fischer, curator of the Egyptian Collection at the MMA, an anonymous donation to the MMA made it possible for the LDS Church to acquire the papyri.[97] The subsequent transfer included ten pieces of papyri, including the original of Facsimile 1.[98] The eleventh fragment had been given to Brigham Young (then church president) previously by Chief Banquejappa of the Pottawatomie tribe in 1846.[99]

Three of these fragments were designated Joseph Smith Papyrus (JSP) I, X, and XI.[100] Other fragments, designated JSP II, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII, are thought by critics to be the Book of Joseph to which Smith had referred. Egyptologist John A. Wilson stated that the recovered fragments indicated the existence of at least six to eight separate documents.[101] The twelfth fragment was discovered in the LDS Church Historian's office and was dubbed the "Church Historian's Fragment". Disclosed by the church in 1968, the fragment was designated JSP IX.[102] Although there is some debate about how much of the papyrus collection is missing, there is broad agreement that the recovered papyri are portions of Smith's original purchase, partly based on the fact that they were pasted onto paper which had "drawings of a temple and maps of the Kirtland, Ohio area" on the back, as well as the fact that they were accompanied by an affidavit by Emma Smith stating that they had been in the possession of Joseph Smith.[103]

Controversy and criticism

Since its publication in 1842, the Book of Abraham has been a source of controversy. Non-Mormon Egyptologists, beginning in the late 19th century,[73] have disagreed with Joseph Smith's explanations of the facsimiles. They have also asserted that damaged portions of the papyri have been reconstructed incorrectly. In 1912, the book 'Joseph Smith, Jr., As a Translator' was published, containing refutations to Smith's translations. Refuters included Archibald Sayce, Flinders Petrie, James Henry Breasted, Arthur Cruttenden Mace (refute below), John Punnett Peters, C. Mercer, Eduard Meyer, and Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissing.[104]

I return herewith, under separate cover, the 'Pearl of Great Price.' The 'Book of Abraham,' it is hardly necessary to say, is a pure fabrication. Cuts 1 and 3 are inaccurate copies of well known scenes on funeral papyri, and cut 2 is a copy of one of the magical discs which in the late Egyptian period were placed under the heads of mummies. There were about forty of these latter known in museums and they are all very similar in character. Joseph Smith's interpretation of these cuts is a farrago of nonsense from beginning to end. Egyptian characters can now be read almost as easily as Greek, and five minutes' study in an Egyptian gallery of any museum should be enough to convince any educated man of the clumsiness of the imposture.

The controversy intensified in the late 1960s when portions of the Joseph Smith Papyri were located. The translation of the papyri by both Mormon and non-Mormon Egyptologists does not match the text of the Book of Abraham as purportedly translated by Joseph Smith.[105] Indeed, the transliterated text from the recovered papyri and facsimiles published in the Book of Abraham contain no direct references, either historical or textual, to Abraham,[95][106][94] and Abraham's name does not appear anywhere in the papyri or the facsimiles. Edward Ashment notes, "The sign that Smith identified with Abraham [...] is nothing more than the hieratic version of [...] a 'w' in Egyptian. It has no phonetic or semantic relationship to [Smith's] 'Ah-broam.'"[106] University of Chicago Egyptologist Robert K. Ritner concluded in 2014 that the source of the Book of Abraham "is the 'Breathing Permit of Hôr,' misunderstood and mistranslated by Joseph Smith",[107] and that the other papyri are common Egyptian funerary documents like the Book of the Dead.[98]

Original manuscripts of the Book of Abraham, microfilmed in 1966 by Jerald Tanner, show portions of the Joseph Smith Papyri and their purported translations into the Book of Abraham. Ritner concludes, contrary to the LDS position, due to the microfilms being published prior to the rediscovery of the Joseph Smith Papyri, that "it is not true that 'no eyewitness account of the translation survives'", that the Book of Abraham is "confirmed as a perhaps well-meaning, but erroneous invention by Joseph Smith", and "despite its inauthenticity as a genuine historical narrative, the Book of Abraham remains a valuable witness to early American religious history and to the recourse to ancient texts as sources of modern religious faith and speculation".[107]

Book of Joseph

As noted above, a second untranslated work was identified by Joseph Smith after scrutinizing the original papyri. He said that one scroll contained "the writings of Joseph of Egypt". Based on descriptions by Oliver Cowdery, some, including Charles M. Larson, believe that the fragments Joseph Smith Papyri II, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII are the source of this work.[108][nb 6]

See also

Notes

- ^ The name of the individual for whom the "Breathing Permit" was intended has variously been rendered as "Hôr" (e.g. Ritner 2013, p. 6), "Hor" (e.g. Rhodes 2005), "Horos" (e.g. Ritner 2013, p. 71), and "Horus" (e.g. Marquardt, H. Michael, Breathing Permit of Horus, retrieved August 9, 2016).

- ^ Facsimile No. 1 and Chapter 1 through chapter 2 verse 18 are to be found in Volume III, No. 9, dated March 1, 1842; Facsimile No. 2 and chapter 2 verses 19 through chapter 5 are to be found in Volume III, No. 10, dated March 15, 1842; Facsimile No. 3 is to be found in Vol. III, No. 14, dated May 16, 1842.[19]

- ^ The identities of the gods themselves are unspecified in the Book itself, but the LDS Church teaches that God the Father (Elohim), Jesus Christ (Jehovah), Adam (Michael), and "many of the great and noble ones" (Abraham 3:22) participated in the creation.[68]

- ^ In 1896, two leaders of the church at the time, Joseph Smith III and Heman C. Smith, made the following observation on the Book of Abraham: "The church has never to our knowledge taken any action on this work, either to indorse [sic] or condemn; so it cannot be said to be a church publication; nor can the church be held to answer for the correctness of its teaching. Joseph Smith, as the translator, is committed of course to the correctness of the translation, but not necessarily to the indorsement [sic] of its historical or doctrinal contents.[87]

- ^ Despite the sale of the mummies and papyri, Bidamon kept in his possession the ten page "'Book of Abraham' Translation Manuscript I", which he later passed onto his son, Charles. The younger Bidamon then sold this item to LDS collector Wilford Wood in 1937, who subsequently donated it to the Church in the same year.[90]

- ^ Cowdery, in a letter that was published in a Mormon publication, described the papyrus scroll that supposedly contained the Book of Joseph, noting: "The representation of the god-head—three, yet in one, is curiously drawn to give simply, though impressively, the writer's view of that exalted personage. The serpent, represented as walking, or formed in a manner to be able to walk, standing in front of, and near a female figure, is to me, one of the greatest representations I have ever seen upon paper […] Enoch's Pillar, as mentioned by Josephus, is upon the same [scroll]."[109] Larson argues that many of these figures (e.g. the god-head, a snake with legs, and a pillar) can be found on JSP II, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII.[110]

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b Gee 2000a, pp. 4–6

- ^ Smith 1842, p. 704.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 8

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Rhodes 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Smith et al. 1902, p. 236.

- ^ Ritner 2013, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Ritner 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Gee 2000a, p. 3.

- ^ "Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–C [Abraham 1:1–2:18]," p. 1, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 24, 2019, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/book-of-abraham-manuscript-circa-july-circa-november-1835-c-abraham-11-218/1

- ^ Smith et al. 1902, p. 238.

- ^ Jessee 2002, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Ritner 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Ritner 2013, pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b Ritner 2013, p. 21.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 27.

- ^ Smith 1842.

- ^ Warren Parrish, letter to the editor, Painesville Republican, 15 February 1838

- ^ Wilford Woodruff journal, February 19, 1842

- ^ Parley P. Pratt, “Editorial Remarks,” Millennial Star 3 (July 1842): 47. "The record is now in course of translation by means of the Urim and Thummim, and proves to be a record written partly by the father of the faithful, Abraham, and finished by Joseph when he was in Egypt." http://www.latterdaytruth.org/pdf/100302.pdf

- ^ West, William S. A few Interesting Facts Respecting the Rise and Progress and Pretensions of the Mormons 1837. http://www.olivercowdery.com/smithhome/1830s/1837West.htm pg. 5

- ^ a b c d e f "The Book of Abraham". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Givens & Hauglid 2019, p. 181.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Mark L. (2020). "Scriptures through the Jeweler's Lens". Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (review). 36: 85–108.

- ^ Bushman 2005, p. 132.

- ^ Abraham 1:6

- ^ Chase 2014, p. 165.

- ^ Ritner 2013, pp. 26, 58.

- ^ Chase 2014, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Chase 2014, p. 169.

- ^ Chase 2014, pp. 173–180.

- ^ a b c Chase 2014, p. 204.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 40.

- ^ a b Ritner 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 52.

- ^ a b Ritner 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Larson 1992, pp. 17–18.

- ^ John Taylor, the editor of the Times and Seasons, wrote in 1843, "We would further state that we had the promise of Br. Joseph, to furnish us with further extracts from the Book of Abraham". February 1843 edition of the Times and Seasons. see http://thebookofabraham.blogspot.com/2011/07/times-and-seasons-jt-1843.html

- ^ Oliver Cowdery, Kirtland, OH, to William Frye, Lebanon, IL, 22 Dec. 1835 http://thebookofabraham.blogspot.com/2011/01/messenger-and-advocate-december-1835.html

- ^ William S. West, A Few Interesting Fads, Respecting the Rise, Progress and Pretensions of the Mormons (Warren, Ohio, 1837), 5.

- ^ Chase 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Abraham 1:1–4.

- ^ Abraham 3.

- ^ Abraham 2:10.

- ^ Abraham 3:18–28.

- ^ Abraham 4:1.

- ^ Abraham 3:22–23.

- ^ Abraham 1:21

- ^ Abraham 1:27.

- ^ Mauss 2003, p. 238,

- ^ Bringhurst 1981, p. 193.

- ^ a b Folkman, Kevin. "Gee, 'Introduction to the Book of Abraham'". Dawning of a Brighter Day (review). Association of Mormon Letters. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Reeve, W. Paul (2015). Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975407-6.

- ^ Dialogue. Dialogue Foundation. 2001. p. 267.

- ^ Official Declaration 2, 'Every Faithful, Worthy Man'. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2002. pp. 634–635.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 59.

- ^ a b Abraham 3:4.

- ^ Abraham 3:3–16.

- ^ "Kolob". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Abraham 3:2-3.

- ^ a b c d Church Education System 2000, pp. 28–41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham". Gospel Topics Essays. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. July 2014. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Abraham 3:18–19.

- ^ Abraham 3:26.

- ^ "Second Estate". Brigham Young University. Archived from the original on 2016-09-23. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ "Doctrines of the Gospel Student Manual Chapter 7: The Creation". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ Ritner 2013, pp. 31–33, 40.

- ^ Ritner 2013, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Ritner 2013, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d Ritner 2013, p. 61.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 306.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 326.

- ^ Ritner 2013, p. 310.

- ^ Givens & Hauglid 2019, pp. 121–124.

- ^ McConkie 1966, pp. 100, 563.

- ^ "None of the characters on the papyrus fragments mentioned Abraham’s name or any of the events recorded in the book of Abraham. Mormon and non-Mormon Egyptologists agree that the characters on the fragments do not match the translation given in the book of Abraham, though there is not unanimity, even among non-Mormon scholars, about the proper interpretation of the vignettes on these fragments. Scholars have identified the papyrus fragments as parts of standard funerary texts that were deposited with mummified bodies. These fragments date to between the third century B.C.E. and the first century C.E., long after Abraham lived." (From "Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham")

- ^ a b Gee, John (2017). "The Relationship of the Book of Abraham Text to the Papyri". An Introduction to the Book of Abraham. Provo: Religious Studies Center. pp. 83–86. ISBN 978-1-9443-9406-6.

- ^ a b Holyoak, Trevor (December 19, 2019). "Book Review: The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism's Most Controversial Scripture". FAIR. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ In support of his interpretation, Gee has proposed that the original surviving portion of the Breathing Permit of Hôr (of which 66 centimeters survive) was more than 1,300 centimeters long, based on his use of Friedhelm Hoffman's formula for calculating scroll length based on extant fragments. However, when Andrew W. Cook and Christopher Smith "attempted to replicate Gee’s results" with similar calculations in another study of the Breathing Permit, they "found that his measurements did not seem to be accurate" and instead estimated that no more than 56 centimeters are missing from the original scroll. See Gee, John (2008). "Some Puzzles from the Joseph Smith Papyri". FARMS Review. 20 (1): 113–137. doi:10.5406/farmsreview.20.1.0113. S2CID 171273003. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020 – via BYU ScholarsArchive; Cook, Andrew W. (Winter 2010). "The Original Length of the Scroll of Hôr" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 43 (4): 1–42. doi:10.5406/dialjmormthou.43.4.0001. S2CID 171454962. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2021; Givens & Hauglid (2019, pp. 159, 214n234). In a historical apparatus for the Joseph Smith Papyri, the Joseph Smith Papers describes the Permit as having originally been "between 150 and 156 centimeters", based on citations from Cook, Smith, and other scholars: "Introduction to Egyptian Papyri, circa 300–100 BC". The Joseph Smith Papers. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Givens & Hauglid 2019, p. 180.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 130–133.

- ^ Hauglid, Brian M.; Jensen, Robin (January 11, 2019). "A Window into Joseph Smith's Translation". Maxwell Institute (published January 29, 2019). Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved May 25, 2021 – via YouTube.

It is clear that Joseph Smith and/or his clerks associated the characters from the papyri with the English Book of Abraham text.

- ^ Stokes, Adam Oliver (2018). "John Gee. 'An Introduction to the Book of Abraham'". BYU Studies Quarterly (review). 57 (1): 202–205.

- ^ Smith & Smith 1896, p. 569.

- ^ "Scriptures". Strangite.org. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ "Mediation and Atonement". Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c Ritner 2013, p. 62.

- ^ Peterson 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Todd, Jay M. (1992). "Papyri, Joseph Smith". In Ludlow, Daniel H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 1058–1060. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018.

- ^ Todd 1992.

- ^ a b Ritner 2013, p. 66.

- ^ a b Reeve & Parshall 2010, p. 269.

- ^ a b c Ritner 2013, p. 64.

- ^ a b Wade et al. 1967, p. 64.

- ^ a b Ritner 2013, p. 65.

- ^ Improvement Era, February 1968, pp. 40–40H.

- ^ Barney 2006.

- ^ Wilson et al. 1968, p. 67.

- ^ Ritner 2013, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Deseret News, Salt Lake City, November 27, 1967.

- ^ Spalding, F. S. (Franklin Spencer) (1912). Joseph Smith, Jr., as a translator : an inquiry. Harold B. Lee Library. Salt Lake City, Utah : F.S. Spalding.

- ^ Larson 1992, p. 61.

- ^ a b Ashment 2000, p. 126.

- ^ a b Ritner, Robert K., A Response to 'Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham', Signature Books, archived from the original on November 19, 2015, retrieved January 19, 2016

- ^ Larson 1992, pp. 81–87.

- ^ Larson 1992, p. 82.

- ^ Larson 1992, pp. 82–84.

Bibliography

- Ashment, Edward H (December 1979), "The Facsimilies of the Book of Abraham: A Reappraisal", Sunstone, 17 (18).

- Ashment, Edward H (December 2000), "Joseph Smith's Identification of "Abraham" in Papyrus JS1, the "Breathing Permit of Hor"", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 33 (4): 121–126, doi:10.2307/45226744, JSTOR 45226744, S2CID 254298749.

- Baer, Klaus (November 1968), "The Breathing Permit of Hor: A Translation of the Apparent Source of the Book of Abraham", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 3 (3): 109–154, doi:10.2307/45224026, JSTOR 45224026, S2CID 254387471, retrieved May 30, 2007.

- G, D. L (February 1968), New Light on Joseph Smith's Egyptian Papyri: Additional Fragment Disclosed, vol. 71, Improvement Era, p. 40, retrieved August 9, 2016.

- Barney, Kevin (2006), "The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources", in Gee, John; Hauglid, Brian M (eds.), Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant (PDF), Brigham Young University, ISBN 9780934893763, archived from the original (PDF) on May 26, 2021

- Bringhurst, Newell (1981), Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism, Greenwood Press, ISBN 9780313227523.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780307426482.

- Chase, Randal S. (2014), Pearl of Great Price Study Guide, Plain & Precious Publishing, ISBN 9781937901134.

- Church Education System (2000), The Pearl of Great Price Study Guide (PDF), The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- Gee, John (1991), Notes on the Sons of Horus, Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies.

- Gee, John (2000a), A Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri, Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, ISBN 9780934893541.

- Givens, Terryl; Hauglid, Brian M. (2019). The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism's Most Controversial Scripture. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190603861.

- Jessee, Dean (2002), Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, Deseret Book, ISBN 9781573457873

- Larson, Charles M. (1992), By His Own Hand Upon Papyrus (2 ed.), Institute of Religious Research, ISBN 9780962096327.

- Barney, Kevin L. (2005), "The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources", in Gee, John; Hauglid, Brian M. (eds.), Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, pp. 107–130, ISBN 978-0934893763.

- Mauss, Armand (2003), All Abraham's Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 9780252028038.

- McConkie, Bruce R. (1966). Mormon Doctrine. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft – via Internet Archive.

- Millet, Robert L. (February 1998), "The Man Adam", Liahona, retrieved August 4, 2016.

- Nibley, Hugh (1975), The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment, Deseret Book Co., ISBN 9781590385395.

- Peterson, H. Donl (1995), Story of the Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism, Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, ISBN 9780875798462.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1998), Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (2nd ed.), Signature Books, ISBN 9781560850892.

- Reeve, W. Paul; Parshall, Ardis, eds. (2010), "Mormon Scripture", Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 9781598841084.

- Rhodes, Michael D. (Spring 1977), Translation of Fac. #2, BYU Studies Quarterly, retrieved August 4, 2016.

- Rhodes, Michael (1988), I Have a Question, Ensign, pp. 51–53, retrieved August 9, 2016

- Rhodes, Michael D (1992), "The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture", FARMS Review of Books, 4 (1), Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies: 120–126, doi:10.2307/44796511, JSTOR 44796511, S2CID 55005625, archived from the original on July 4, 2003, retrieved May 30, 2007.

- Rhodes, Michael (2003), Teaching the Book of Abraham Facsimiles, vol. 4, The Religious Educator, pp. 115–23.

- Rhodes, Michael D (2005), The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary, Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, ISBN 9780934893633.

- Ritner, Robert K. (December 2000), "The "Breathing Permit of Hor" Thirty Four Years Later", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 33 (4): 97–119, doi:10.2307/45226742, JSTOR 45226742, S2CID 254348028, retrieved May 30, 2007.

- Ritner, Robert K. (July 2003), "'The Breathing Permit of Hôr' Among the Joseph Smith Papyri", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 62 (3): 161–180, doi:10.1086/380315, S2CID 162323232.

- Ritner, Robert K. (2013), The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri: A Complete Edition, Signature Books, ISBN 9781560852209.

- Smith, Christopher C. (Spring–Summer 2011), ""That Which Is Lost": Assessing the State of Preservation of the Joseph Smith Papyri", John Whitmer Historical Association Journal, 31 (1): 69–83.

- Smith, Joseph, III; Smith, Heman C. (1896), The History of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, vol. 2, Herald Publishing House, ISBN 9781601357106

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Smith, Joseph; et al. (1902), History of the Church, vol. 2, retrieved August 9, 2016.

- Smith, Joseph (March 1, 1842), "Truth Will Prevail", Times and Seasons, vol. 3, no. 9, Nauvoo, IL, p. 704

- Smith, Milan D. Jr (December 1990), "That is the Handwriting of Abraham", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 23 (4): 167–169, doi:10.2307/45225946, JSTOR 45225946, S2CID 254312026.

- Spalding, F. S. (1912), Joseph Smith, Jr. As a Translator: An Inquiry, Arrow Press, retrieved October 30, 2016.

- Stenhouse, T. B. H. (1873), The Rocky Mountain Saints, D. Appleton and Company.

- Wade, Glen; Tolk, Norman; Travers, Lynn; Smith, George D; Graves, F. Charles (Winter 1967), "The Facsimile Found", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought: 51–64, archived from the original on August 19, 2016, retrieved August 7, 2016.

- Wilson, John A; Parker, Richard A; Howard, Richard A; Hewerd, Grant S; Jerald, Tanner; Hugh, Nibley (August 1968), "The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 3 (2): 67–105, doi:10.2307/45227259, JSTOR 45227259, S2CID 254343491, retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Webb, Robert C. (1915), The Case Against Mormonism, L. L. Walton.

External links

- Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham, from the LDS Church website

- The Pearl of Great Price (containing the Book of Abraham), from the LDS Church website

- Book of Abraham manuscript materials from The Joseph Smith Papers