Gostivar: Difference between revisions

Square of Gostivar on the top Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Reverted Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

| blank1_info = [[Oceanic climate|Cfb]] |

| blank1_info = [[Oceanic climate|Cfb]] |

||

| footnotes = |

| footnotes = |

||

| population_demonym = ([[Albanian language|Albanian]]: Gostivaras/Gostivarase) |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 09:30, 7 October 2023

Gostivar

Gostivari Гостивар (Macedonian) | |

|---|---|

From the top:Square of Gostivar, Clock Tower and Clock Tower Mosque, City Park next to the Vardar River | |

Location in Northwestern North Macedonia | |

| Coordinates: 41°48′N 20°55′E / 41.800°N 20.917°E | |

| Country | North Macedonia |

| Region | |

| Municipality | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Arben Taravari (AA) |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.341 km2 (0.518 sq mi) |

| Population (2021) | |

• Total | 32,814 |

| Demonym | (Albanian: Gostivaras/Gostivarase) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | gostivari.gov.mk |

Gostivar (Template:Lang-mk [ˈɡɔstivar] ⓘ, Albanian and Turkish: Gostivar), is a city in North Macedonia, located in the upper Polog valley region. It is the seat of one of the larger municipalities in the country with a population of 59,770,[1] and the town also covers 1.341 square kilometres (331 acres). Gostivar has road and railway connections with the other cities in the region, such as Tetovo, Skopje, Kičevo, Ohrid, and Debar. A freeway was built in 1995, from Gostivar to Tetovo, 24 km (15 mi) long. Gostivar is the seat of Gostivar Municipality.

Etymology

The name Gostivar comes from the Slavic word gosti meaning "guests" and the Turkish word "dvar" meaning castle or fort.[2]

Geography

Gostivar, at an elevation of 535 meters, is situated on the foothills of one of the Šar Mountains. Near to Gostivar is the village of Vrutok, where the Vardar river begins at an altitude of 683 meters (2,241 ft) from the base of the Šar Mountains. Vardar River extends through Gostivar, cutting it in half, passes through the capital Skopje, goes through the country, enters Greece and finally reaches the Aegean Sea.

Demographics

In statistics gathered by Bulgarian researcher Vasil Kanchov in 1900, the city of Gostivar was inhabited by 3735 people, of whom 3100 were Turks, 310 Christian Bulgarians, 200 Romani, 150 Muslim Albanians and 25 Vlachs.[3] Kanchov wrote in 1900 that many Albanians declared themselves as Turks. In Gostivar, the population that declared itself Turkish "was of Albanian blood", but it "had been Turkified after the Ottoman invasion, including Skanderbeg", referring to Islamization.[4]

The researcher Dimitar Gađanov wrote in 1916 that Gostivar was populated by 4,000 Albanians "who were Turkified", 100 Orthodox Albanians and 3,500 Bulgarians, while the surrounding area was predominantly Albanian.[4]

According to the 2002 census, the city of Gostivar had a population of 35,847 inhabitants and the ethnic composition is the following:[5]

- Albanians, 16,890 (47.1%)

- Macedonians, 11,885 (33.2%)

- Turks, 4,559 (12.7%)

- Romas, 1,899 (5.3%)

- others, 614 (1.7%)

The most common mother tongues in the city were the following:

- Albanian, 16,877 (47.1%)

- Macedonian, 13,843 (38.6%)

- Turkish, 4,423 (12.3%)

- Romani, 301 (0.8%)

- Serbian, 124 (0.3%)

- others, 279 (0.7%)

The religious composition of the city was the following:

- Muslims, 23,686 (66.1%)

- Orthodox Christians, 11,865 (33.1%)

- others, 296 (0.8%)

| Ethnic group |

census 1948 | census 1953 | census 1961 | census 1971 | census 1981 | census 1994 | census 2002 | census 2021 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Macedonians | .. | .. | 2,637 | 27.7 | 5,092 | 39.8 | 8,109 | 41.7 | 10,127 | 36.5 | 12,084 | 36.7 | 11,885 | 33.2 | 10,305 | 31.4 |

| Albanians | .. | .. | 4,313 | 45.4 | 2,904 | 22.7 | 6,044 | 31.1 | 10,791 | 38.9 | 14,128 | 42.3 | 16,890 | 47.1 | 13,585 | 41.4 |

| Turks | .. | .. | 1,924 | 20.2 | 4,349 | 34.0 | 4,449 | 22.9 | 4,378 | 15.8 | 4,475 | 13.6 | 4,559 | 12.7 | 4,725 | 14.4 |

| Romani | .. | .. | 353 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 219 | 1.1 | 1254 | 4.5 | 1,609 | 4.9 | 1,899 | 5.3 | 1,648 | 5.0 |

| Vlachs | .. | .. | 11 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 11 | 0.0 | 15 | 0.0 | 14 | 0.0 |

| Serbs | .. | .. | 133 | 1.4 | 249 | 2.0 | 254 | 1.3 | 233 | 0.9 | 233 | 0.7 | 146 | 0.4 | 65 | 0.0 |

| Bosniaks | .. | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 34 | 0.1 | 21 | 0.0 |

| Others | .. | .. | 138 | 1.4 | 193 | 1.5 | 392 | 2.0 | 947 | 3.4 | 388 | 1.2 | 419 | 1.2 | 455 | 1.4 |

| Persons for whom data are taken from administrative sources | 1,996 | 6.1 | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 7,832 | 9,509 | 12,787 | 19,467 | 27,726 | 32,926 | 35,847 | 32,814 | ||||||||

History

It is known that there was a town called Draudacum, Draudàkon (Δραυδάκον in Ancient Greek), built in 170 BCE, near or on the current locality of Gostivar.[citation needed]

Early mentions of the town was made by the Roman historian Livy. He records how during the Third Macedonian War the King of Macedon Perseus at the head of 10000 men, after taking Uskana (Kicevo), attacked Drau-Dak, today Gostivar.[citation needed]

Ottoman Period

In the late 14th century, Gostivar came under Ottoman rule along with the rest of Vardar Macedonia.[citation needed]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Gostivar was part of the Kosovo Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. During this period it became the centre of a kaza (municipality) and grew into one of the richer towns of Ottoman Vardar Macedonia.[citation needed]

Gostivar remained under Ottoman rule for more than 500 years until 1912, when it was occupied by Serbian troops during the First Balkan War.[citation needed]

Yugoslav Period

Jordan Ivanov, professor at the University of Sofia, wrote in 1915 that Albanians, since they did not have their own alphabet, due to a lack of consolidated national consciousness and influenced by foreign propaganda, declared themselves as Turks, Greeks and Bulgarians, depending on which religion they belonged to. The Orthodox Albanians of Gostivar were Bulgarianized by due to them being near the Bulgarian population.[4]

From 1929 to 1941, Gostivar was part of the Vardar Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and then became part of Italian-occupied Albania.[citation needed]

From the 1950s onwards Orthodox Christian Albanian speakers from Upper Reka migrated cities like Gostivar, where they form the main population of Durtlok neighbourhood.[7][8][9]

A policy of Turkification of the Albanian population was employed by the Yugoslav authorities in cooperation with the Turkish government, stretching the period of 1948-1959. A commission was created to tour Albanian communities in Macedonia, visiting Gostivar amongst other cities. Starting in 1948, six Turkish schools were opened in areas with large Albanian majorities, such as Tearce, Gorna Banjica, Dolna Banjica Vrapčište as well as in the outskirts of Tetovo and Gostivar.[10] Contemporary analysis described cases of resistance to the Turkish schools in the Polog area, with Albanian speaking students and teachers refused to attend Turkish schools. A notable case happened in Gostivar, where a teacher from Banjica, who according to the committees analysis: "even though he was born in the same village and his mother tongue is Turkish, when the Turkish school was opened he refused to teach in Turkish and had asked to work in Albanian villages ...". Thus the Yugoslav committee characterized the local population as having adopted a "Greater Albanian political worldview". Resistance against the opening of Turkish schools was most prevalent in Tetovo and Gostivar. In Gostivar the nationalist activist Myrtezan Bajraktari was detained and interrogated by the Yugoslav secret police (UDBA). During his interrogation he stated he openly opposed the Turkish schools, and that he does so "just so Albanians can feel like patriots and not allow themselves to be Turkified."[11]

Economy

In May 2015, an automotive company announced that it would open a new plant in Gostivar in the summer of 2015.[12]

Tourism

Leaving Gostivar on the way to Ohrid, the village Vrutok has the gorge of the biggest river in North Macedonia, Vardar, which is 388 km (241 mi) long and flows into the Aegean Sea, at Thessaloniki. Gostivar is one of the biggest settlements in the Polog valley. The Polog valley can be observed from the high lands of Mavrovo and Galičnik.[citation needed]

The Mavrovo region hosts ski tournaments and other sport recreations. The peaks on the northern part of the Bistra mountain: Rusino Brdo, Sultanica and Sandaktas, host winter sport activities.[citation needed]

The range is 80 km (50 mi) long and 12 km (7 mi) wide and is covered with snow from November till March or April every year. Its highest peak, Titov Vrv, is situated on 2,760 meters (9,055 ft) above sea level.[citation needed] This provides opportunities for animal husbandry. Dairy products, mainly cheese and feta cheese, are made in the many sheepfolds on Šar and the adjacent mountains. These include several kinds of feta cheese, like Shara and Galicnik.[citation needed]

Located in the northwestern part of North Macedonia, Popova Shapka is another winter ski resort. It is situated on the Šar Mountain, 1,780 meters (5,840 ft) above the sea level, just 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the capital Skopje. Popova Shapka has hotel accommodation.[citation needed]

Visitors not from the Republic of North Macedonia, and elsewhere other countries, use the facilities. Popova Shapka has been a host to both the European and Balkan Ski Championships. Not far from the resort, there are a number of small glacial lakes around on the mountain. There are two ways to get to Popova Shapka: by car, and by rope-railway with a starting location in Tetovo. The rope-railway is 6 km (4 mi) long and it takes about 36 minutes to reach the top.[citation needed]

Sports

Football club KF Gostivar has played in the Macedonian First League and stage their home games at the City Stadium Gostivar.

Notable people

References

- ^ 2002 Census results

- ^ Evans, Thammy; Briggs, Philip (2019). North Macedonia : the Bradt travel guide (Sixth ed.). Bucks, England. p. 176. ISBN 978-1784770846.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vasil Kanchov (1900). Macedonia: Ethnography and Statistics. Sofia. p. 252.

- ^ a b c Salajdin SALIHI. "DISA SHËNIME PËR SHQIPTARËT ORTODOKSË TË REKËS SË EPËRME". FILOLOGJIA - International Journal of Human Sciences 19:85-90.

- ^ Macedonian Census (2002), Book 5 - Total population according to the Ethnic Affiliation, Mother Tongue and Religion, The State Statistical Office, Skopje, 2002, p. 87, 224, 361.

- ^ Censuses of population 1948 - 2002 Archived 2013-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mirčevska 2007, p. 138."Некои од нив имаат куќи во кои престојуваат во текот на летните месеци, додека другиот дел од годината живеат во Гостивар и Скопје, заедно со семејствата на синовите. [Some of them have houses staying there during the summer months, while during the other part of the year living in Gostivar and Skopje, along with the families of their children.]"; p. 162. "На пример, во Белград, каде и денес живее релативно голем број на горнореканцко македонско население, познати се како Рекалии. [For example, in Belgrade, where today lives a relatively large number of Macedonian Upper Rekan population, who are known as Rekalii.]"

- ^ Murati 2011, p. 123. "Namik Durmishi, mësimdhënës në Universitetin e Tetovës, edhe vetë nga Zhuzhnja e Rekës së Epërme, në një lagje të quajtur Durtllok të Gostivarit, të populluar kryesisht me rekas ortodoksë nga të kësaj krahine, maqedonasit atyre u thonë si me përbuzje Shkreta/Shkreti: Kaj si bre škreta, me cilësimin pezhorativ "shqiptarë të shkretë, që kanë ardhur nga një krahinë e shkretë, njerëz viranë". [Namik Durmishi, teaching at the University of Tetovo, who also is from Žužnje, Upper Reka in a neighbourhood called Durtlok in Gostivar, populated mostly by Orthodox Rekans cites that Macedonians when referring to them in disdain say Shkreta/Shkreti: Where are you from Shkreti, which has pejorative connotations of "the poor Albanian who came from a desolate region, an abandoned people.]"

- ^ Pieroni et al. 2013, pp. 2–3."Locals are now exclusively Muslims, but Albanians of Christian Orthodox faith also lived in the villages until a few decades ago. For example, in Nistrovë, one side of the village (with a mosque) is inhabited by Muslims, while the other side was inhabited by Orthodox believers. The entire population of Orthodox Christians migrated to towns a few decades ago, but they return to their village homes sometimes during the summer. Most of the houses in this part of the village are however abandoned even though the Church has been recently restored. According to our (Albanian Muslim) informants, these migrated Orthodox Christian Albanians assimilated within the Macedonian culture and now prefer to be labelled as "Macedonians", even if they are still able to fluently speak Albanian. Contact between these two subsets of the village communities, which were very intense and continuous in the past, no longer exists today. All Albanian inhabitants of the upper Reka are – to different degrees depending on the age – bilingual in Macedonian."

- ^ Lita, Qerim (2009). "SHPËRNGULJA E SHQIPTARËVE NGA MAQEDONIA NË TURQI (1953-1959)". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH: 75-82.

- ^ Lita, Qerim (2009). "SHPËRNGULJA E SHQIPTARËVE NGA MAQEDONIA NË TURQI (1953-1959)". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH: 82.

- ^ "Lear Corp. (LEA) to Open Automotive Plant in Macedonia" (Press release). Nasdaq. May 19, 2015.

Works cited

- Mirčevska, Mirjana P. (2007). Verbalni i neverbalni etnički simboli vo Gorna Reka [Verbal and non-verbal ethnic symbols in Upper Reka]. Skopje: Institut za Etnologija i Antropologija. ISBN 978-9989-668-66-1.

- Murati, Qemal (2011). "Gjuha e humbur: Vëzhgime historike, linguistike, onomastike dhe folklorike rreth shqiptarëve ortodoksë në etnoregjionin e Rekës së Epërme të Mavrovës [Lost Language: Historical, Linguistic, Onomastic and Folkloric observations about the Orthodox Albanians in ethno-region of Upper Reka in Mavrovo]". Studime Albanologjike. 3: 87–133.

- Pieroni, Andrea; Rexhepi, Besnik; Nedelcheva, Anely; Hajdari, Avni; Mustafa, Behxhet; Kolosova, Valeria (2013). "One century later: the folk botanical knowledge of the last remaining Albanians of the upper Reka Valley, Mount Korab, Western Macedonia". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 9 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-9-22. PMC 3648429. PMID 23578063.

External links

Gallery

-

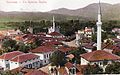

Gostivar at 1921

-

Gostivar at 1929

-

Gostivar at 1930

-

Gostivar at 1930

-

Gostivar at 1935