Culture of Egypt: Difference between revisions

Reverted 1 edit by Humanity'sHistorian (talk): Rv mass additions of spelling errors and other badly written content |

Undid revision 1180638047 by MrOllie (talk) fixed typos and grammar errors. added sourced information crucial to educating readers about egyptian culture Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Pattern of human activity and symbolism associated with Egypt and its people}} |

{{Short description|Pattern of human activity and symbolism associated with Egypt and its people}} |

||

{{Life in Egypt}} |

|||

The '''culture of Egypt''' has thousands of years of [[recorded history]]. [[Ancient Egypt]] was among the earliest [[civilizations]] in the world. For millennia, [[Egypt]] developed strikingly unique, complex and stable cultures that influenced other cultures of [[Europe]], [[Africa]] and the [[Middle East]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Egyptian Identity|url=https://www.ucl.ac.uk/3dpetriemuseum/stories/ancient-life/egyptian-life/egyptian-identity.html|access-date=2021-03-04|website=www.ucl.ac.uk}}</ref> |

The '''culture of Egypt''' has thousands of years of [[recorded history]]. [[Ancient Egypt]] was among the earliest [[civilizations]] in the world. For millennia, [[Egypt]] developed strikingly unique, complex, and stable cultures that influenced other cultures of [[Europe]], [[Africa]] and the [[Middle East]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Egyptian Identity|url=https://www.ucl.ac.uk/3dpetriemuseum/stories/ancient-life/egyptian-life/egyptian-identity.html|access-date=2021-03-04|website=www.ucl.ac.uk}}</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| Line 7: | Line 8: | ||

==Languages== |

==Languages== |

||

{{More citations needed|section|date=March 2017}} |

|||

[[File:Cultural Fashion and Adornment, El Moez St., 00 (70).JPG|thumb|left|[[Arabic calligraphy]] has seen its golden age in [[Cairo]]. This adornment and beads being sold in [[Muizz Street]]]] |

[[File:Cultural Fashion and Adornment, El Moez St., 00 (70).JPG|thumb|left|[[Arabic calligraphy]] has seen its golden age in [[Cairo]]. This adornment and beads being sold in [[Muizz Street]]]] |

||

{{Main|Languages of Egypt}} |

{{Main|Languages of Egypt}} |

||

[[Arabic language|Arabic]] is currently Egypt's official language. It came to Egypt in the 7th century,{{sfn|ʻAbd al-Ḥamīd Yūsuf|2003|p=vii}} and it is the formal and official language of the state which is used by the government and newspapers. Meanwhile, the [[Egyptian Arabic]] dialect or ''Masri'' is the official spoken language of the people. Of the many varieties of Arabic, the Egyptian dialect is the most widely spoken and the most understood, due to the great influence of [[Egyptian cinema]] and the Egyptian media throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Today many foreign students tend to learn it |

[[Arabic language|Arabic]] is currently Egypt's official language. It came to Egypt in the 7th century,{{sfn|ʻAbd al-Ḥamīd Yūsuf|2003|p=vii}} and it is the formal and official language of the state which is used by the government and newspapers. Meanwhile, the [[Egyptian Arabic]] dialect, or ''Masri'' is the official spoken language of the people. Of the many varieties of Arabic, the Egyptian dialect is the most widely spoken and the most understood, due to the great influence of [[Egyptian cinema]] and the Egyptian media throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Today, many foreign students tend to learn it through [[Egyptian music|Egyptian songs]] and movies, and the dialect is usually labelled by the general public as one of the easiest and fastest to learn, mainly due to the huge amount of accessible sources (movies, series, TV shows, books, etc.) that contribute to its learning process.{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} Egypt's position in the heart of the Arabic-speaking world has made it the centre of culture, and its widespread dialect has had a huge influence on almost all neighbouring dialects, having so many Egyptian sayings in their daily lives. {{citation needed|date=June 2020}} |

||

[[Image:Sarcophage Ankhnesneferibre.jpg|thumb|[[Egyptian hieroglyphs|Hieroglyphs]], as this example from a sarcophagus from [[Thebes, Egypt|Thebes]] of about 530 BC, represent both [[ideogram]]s and phonograms.]] |

[[Image:Sarcophage Ankhnesneferibre.jpg|thumb|[[Egyptian hieroglyphs|Hieroglyphs]], as this example from a sarcophagus from [[Thebes, Egypt|Thebes]] of about 530 BC, represent both [[ideogram]]s and phonograms.]] |

||

| Line 16: | Line 18: | ||

The [[Egyptian language]], which formed a separate branch among the family of [[Afro-Asiatic languages]], was among the first written languages and is known from the [[Egyptian hieroglyph|hieroglyphic]] inscriptions preserved on monuments and sheets of [[papyrus]]. The [[Coptic language]], the most recent stage of Egyptian written in mainly [[Greek alphabet]] with seven demotic letters, is today the [[liturgical language]] of the [[Coptic Orthodox Church]].{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} |

The [[Egyptian language]], which formed a separate branch among the family of [[Afro-Asiatic languages]], was among the first written languages and is known from the [[Egyptian hieroglyph|hieroglyphic]] inscriptions preserved on monuments and sheets of [[papyrus]]. The [[Coptic language]], the most recent stage of Egyptian written in mainly [[Greek alphabet]] with seven demotic letters, is today the [[liturgical language]] of the [[Coptic Orthodox Church]].{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} |

||

The "Koiné" dialect of the [[Greek language]] was important in Hellenistic Alexandria, |

The "Koiné" dialect of the [[Greek language]] was important in Hellenistic Alexandria, was used in the philosophy and science of that culture, and was later studied by Arabic scholars.{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} |

||

In the upper Nile Valley, southern Egypt, around [[Kom Ombo]] and south of [[Aswan]], there are about 300,000 speakers of [[Nubian languages]]; mainly [[Nobiin language|Noubi]], but also Kenuzi-Dongola. In Siwa Oasis, there is also the [[Siwi language]] that is spoken by about 20,000 speakers. Other minorities include roughly two thousand [[Greek language|Greek]] speakers in [[Alexandria]] and [[Cairo]] as well as roughly 5,000 [[Armenian language|Armenian]] speakers.{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} |

In the upper Nile Valley, southern Egypt, around [[Kom Ombo]] and south of [[Aswan]], there are about 300,000 speakers of [[Nubian languages]]; mainly [[Nobiin language|Noubi]], but also Kenuzi-Dongola. In Siwa Oasis, there is also the [[Siwi language]] that is spoken by about 20,000 speakers. Other minorities include roughly two thousand [[Greek language|Greek]] speakers in [[Alexandria]] and [[Cairo]] as well as roughly 5,000 [[Armenian language|Armenian]] speakers.{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} |

||

| Line 24: | Line 26: | ||

[[Image:Egypt bookofthedead.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Sample of a Book of the Dead of the [[scribe]] Nebqed, c. 1300 BC.]] |

[[Image:Egypt bookofthedead.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Sample of a Book of the Dead of the [[scribe]] Nebqed, c. 1300 BC.]] |

||

Many [[Egyptians]] believed that when it came to a death of their Pharaoh, they would have to bury the Pharaoh deep inside the Pyramid. |

Many [[Egyptians]] believed that when it came to a death of their Pharaoh, they would have to bury the Pharaoh deep inside the Pyramid. |

||

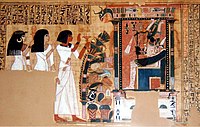

The ancient Egyptian literature dates back to the [[Old Kingdom]], in the third millennium BC. Religious literature is best known for its [[hymns]] to and its mortuary texts. The oldest extant Egyptian literature is the [[Pyramid Texts]]: the mythology and rituals carved around the tombs of rulers. The later, secular literature of ancient Egypt includes the "wisdom texts", forms of philosophical instruction. The ''Instruction of Ptahhotep'', for example, is a collation of moral proverbs by an Egto (the middle of the second millennium BC) seem to have been drawn from an elite administrative |

The ancient Egyptian literature dates back to the [[Old Kingdom]], in the third millennium BC. Religious literature is best known for its [[hymns]] to and its mortuary texts. The oldest extant Egyptian literature is the [[Pyramid Texts]]: the mythology and rituals carved around the tombs of rulers. The later, secular literature of ancient Egypt includes the "wisdom texts", forms of philosophical instruction. The ''Instruction of Ptahhotep'', for example, is a collation of moral proverbs by an Egto (the middle of the second millennium BC) seem to have been drawn from an elite administrative c''a''lss, and were celebrated and revered into the [[New Kingdom of Egypt|New Kingdom]] (to the end of the second millennium). In time, the Pyramid Texts became [[Coffin Texts]] (perhaps after the end of the Old Kingdom), and finally, the mortuary literature produced its masterpiece, the ''[[Book of the Dead]]'', during the New Kingdom.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

||

The [[Middle Kingdom of Egypt|Middle Kingdom]] was the golden age of Egyptian literature. Some texts include the Tale of Neferty, the Instructions of [[Amenemhat I]], the [[The Story of Sinuhe|Tale of Sinuhe]], the Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor and the Story of the Eloquent Peasant. ''Instructions'' became a popular literary genre of the [[New Kingdom of Egypt|New Kingdom]], taking the form of advice on proper |

The [[Middle Kingdom of Egypt|Middle Kingdom]] was the golden age of Egyptian literature. Some texts include the Tale of Neferty, the Instructions of [[Amenemhat I]], the [[The Story of Sinuhe|Tale of Sinuhe]], the Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor and the Story of the Eloquent Peasant. ''Instructions'' became a popular literary genre of the [[New Kingdom of Egypt|New Kingdom]], taking the form of advice on proper behavioru. The [[Story of Wenamun]] and the ''[[Instruction of Any]]'' are examples from this period.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

||

During the [[Greco-Roman|Greco-Roman period]] (332 BC − AD 639), Egyptian literature was translated into other languages, and Greco-Roman literature fused with native art into a new style of writing. From this period comes the [[Rosetta Stone]], which became the key to unlocking the mysteries of Egyptian writing |

During the [[Greco-Roman|Greco-Roman period]] (332 BC − AD 639), Egyptian literature was translated into other languages, and Greco-Roman literature fused with native art into a new style of writing. From this period comes the [[Rosetta Stone]], which became the key to unlocking the mysteries of Egyptian writing for modern scholarship. The city of [[Alexandria]] boasted its [[Library of Alexandria|Library]] of almost half a million handwritten books during the third century BC. Alexandria's center of learning also produced the Greek translation of the [[Hebrew Bible]], the [[Septuagint]]. |

||

[[Image:AkhenatenDwellerInTruth.jpg|thumb|130px|left|''[[Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth]]'', a 1985 novel by Nobel Literature Laureate [[Naguib Mahfouz]].]] |

[[Image:AkhenatenDwellerInTruth.jpg|thumb|130px|left|''[[Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth]]'', a 1985 novel by Nobel Literature Laureate [[Naguib Mahfouz]].]] |

||

During the first few centuries of the Christian era, Egypt was a source of a great deal of ascetic literature in the [[Coptic language]]. Egyptian monasteries translated many [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Syriac language|Syriac]] words, which are now only extant in Coptic. Under [[Islam]], Egypt continued to be a great source of literary |

During the first few centuries of the Christian era, Egypt was a source of a great deal of ascetic literature in the [[Coptic language]]. Egyptian monasteries translated many [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Syriac language|Syriac]] words, which are now only extant in Coptic. Under [[Islam]], Egypt continued to be a great source of literary endeavour, now in the [[Arabic language]]. In 970, [[al-Azhar University]] was founded in Cairo, which to this day remains the most important center of [[Sunni Islamic]] learning. In 12th-century Egypt, the Jewish [[Talmud]]ic scholar [[Maimonides]] produced his most important work. |

||

In contemporary times, Egyptian novelists and poets were among the first to experiment with modern styles of Arabic-language literature, and the forms they developed have been widely imitated. The first modern Egyptian novel ''[[Zaynab (novel)|Zaynab]]'' by [[Muhammad Husayn Haykal]] was published in 1913 in the [[Egyptian Arabic|Egyptian vernacular]]. Egyptian novelist [[Naguib Mahfouz]] was the first Arabic-language writer to win the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]]. Many Egyptian books and films are available throughout the [[Middle East]]. Other Egyptian writers include [[Nawal El Saadawi]], known for her [[feminism|feminist]] works and activism, and [[Alifa Rifaat]] who also wrote about women and tradition. Vernacular poetry is said to be the most popular literary genre amongst Egyptians, represented by [[Mahmud Bayram el-Tunsi|Bayram el-Tunsi]], [[Ahmed Fouad Negm]] (Fagumi), [[Salah Jaheen]] and [[Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi]]. |

In contemporary times, Egyptian novelists and poets were among the first to experiment with modern styles of Arabic-language literature, and the forms they developed have been widely imitated. The first modern Egyptian novel ''[[Zaynab (novel)|Zaynab]]'' by [[Muhammad Husayn Haykal]] was published in 1913 in the [[Egyptian Arabic|Egyptian vernacular]]. Egyptian novelist [[Naguib Mahfouz]] was the first Arabic-language writer to win the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]]. Many Egyptian books and films are available throughout the [[Middle East]]. Other Egyptian writers include [[Nawal El Saadawi]], known for her [[feminism|feminist]] works and activism, and [[Alifa Rifaat]] who also wrote about women and tradition. Vernacular poetry is said to be the most popular literary genre amongst Egyptians, represented by [[Mahmud Bayram el-Tunsi|Bayram el-Tunsi]], [[Ahmed Fouad Negm]] (Fagumi), [[Salah Jaheen]] and [[Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi]]. |

||

| Line 39: | Line 41: | ||

{{Main|Religion in Egypt}} |

{{Main|Religion in Egypt}} |

||

[[Image:Al Azhar1.jpg|thumb|200x120px|right|[[Al-Azhar Mosque]] founded in AD 970 by the Fatimids as the first Islamic University in Egypt.]] |

[[Image:Al Azhar1.jpg|thumb|200x120px|right|[[Al-Azhar Mosque]] founded in AD 970 by the Fatimids as the first Islamic University in Egypt.]] |

||

About |

About 85–95% of Egypt's population is [[Muslim]], with a [[Sunni]] majority. About 5- 15% of the population is [[Coptic Christian]]; other religions and other forms of [[Christianity]] comprise the remaining three percent.<ref>Numbers vary widely. The 1996 census, the last for which public info on religion exists has 5.6% of the population as Christian (down from 8.3% in 1927). However the census may be undercounting Christians. The government Egyptian Demographic and Health Survey (2008) of around 16,500 women aged 15 to 49 showed about 5% of the respondents were Christian. According to [[Al-Ahram|Al-Ahram newspaper]], one of the main government owned national newspapers in Egypt, estimated the percentage between 10% - 15% (2017). QScience Connect in 2013 using 2008 data estimated that 5.1% of Egyptians between the ages of 15 and 59 were Copts. The Pew Foundation estimates 5.1% for Christians in 2010. The CIA Fact Book estimates 10% (2012) while the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs states in 1997, "Estimates of the size of Egypt's Christian population vary from the low government figures of 6 to 7 million to the 12 million reported by some Christian leaders. The actual numbers may be in the 9 to 9.5 million range, out of an Egyptian population of more than 60 million" which yields an estimate of about 10-20% then. Several sources give 10-20%. The British Foreign Office gives a figure of 9%. The Christian Post in 2004 quotes the U.S. Copt Association as reporting 15% of the population as native Christian.</ref> |

||

[[Sunni Islam]] sees Egypt as an important part of its religion due to not only Quranic verses mentioning the country |

[[Sunni Islam]] sees Egypt as an important part of its religion due to not only Quranic verses mentioning the country but also due to the Al-Azhar University, one of the earliest of the world universities. It was created as a school for religious studies and works.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

||

==Visual art<!--'Egyptian painting' and 'Egyptian paintings' redirect here-->== |

==Visual art<!--'Egyptian painting' and 'Egyptian paintings' redirect here-->== |

||

| Line 72: | Line 74: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

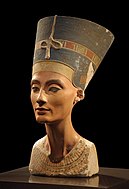

The Egyptians were one of the first major civilizations to codify design elements in [[art]]. The [[wall painting]] done in the service of the [[Pharaohs]] followed a rigid code of visual rules and meanings. Early Egyptian art is |

The Egyptians were one of the first major civilizations to codify design elements in [[art]]. The [[wall painting]] done in the service of the [[Pharaohs]] followed a rigid code of visual rules and meanings. Early Egyptian art is characterised by the absence of [[linear perspective]], which results in a seemingly flat space. These artists tended to create images based on what they knew and not as much on what they saw. Objects in these artworks generally do not decrease in size as they increase in distance, and there is little shading to indicate [[Distance|depth]]. Sometimes, distance is indicated through the use of ''tiered space'', where more distant objects are drawn higher above the nearby objects, but in the same scale and with no overlapping of forms. People and objects are almost always drawn in profile. |

||

Painting achieved its |

Painting achieved its greatest height in [[New Kingdom of Egypt|Dynasty XVII]] during the reigns of Tuthmose IV and [[Amenhotep III]]. The Frfgmentary panel of the Lady Thepu, on the right, dates from the time of the latter king.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Bothmer|first1=Bernard|title=Brief Guide to the Department of Egyptian and Classical Art|date=1974|publisher=Brooklyn Museum|location=Brooklyn, NH|page=48}}</ref> |

||

Early Egyptian artists did have a system for maintaining dimensions within artwork. They used a grid system that allowed them to create a smaller version of the artwork |

Early Egyptian artists did have a system for maintaining dimensions within artwork. They used a grid system that allowed them to create a smaller version of the artwork and then scale up the design based on proportional representation on a larger grid. |

||

=== Egyptian art in modern times === |

=== Egyptian art in modern times === |

||

{{Main|Contemporary Art in Egypt}} |

{{Main|Contemporary Art in Egypt}} |

||

[[Modern art|Modern]] and [[Contemporary art|contemporary]] Egyptian art can be as diverse as any works in the world art scene. Some well-known names include [[Mahmoud Mokhtar]], [[Abdel Hadi Al Gazzar]], [[Farouk Hosny]], [[Gazbia Sirry]], [[Kamal Amin]], [[Hussein El Gebaly]], [[Sawsan Amer]] and many others. Many artists in Egypt have taken on modern media such as digital art and this has been the theme of many exhibitions in [[Cairo]] in recent times. There has also been a tendency to use the World Wide Web as an alternative outlet for artists and there |

[[Modern art|Modern]] and [[Contemporary art|contemporary]] Egyptian art can be as diverse as any works in the world art scene. Some well-known names include [[Mahmoud Mokhtar]], [[Abdel Hadi Al Gazzar]], [[Farouk Hosny]], [[Gazbia Sirry]], [[Kamal Amin]], [[Hussein El Gebaly]], [[Sawsan Amer]] and many others. Many artists in Egypt have taken on modern media such as digital art and this has been the theme of many exhibitions in [[Cairo]] in recent times. There has also been a tendency to use the World Wide Web as an alternative outlet for artists and there are strong Art-focused internet community groups that have found their origins in Egypt. |

||

== Architecture == |

== Architecture == |

||

| Line 86: | Line 88: | ||

==Science== |

==Science== |

||

Egypt's cultural contributions have included great works of [[science]], [[art]], and [[mathematics]], dating from [[Ancient history|antiquity]] to modern times. |

Egypt's cultural contributions have included great works of [[science]], [[art]], and [[mathematics]], dating from [[Ancient history|antiquity]] to modern times. Egypt has produced many brilliant scientists, the most famous of them being [[Ahmed Zewail]], [[Sameera Moussa]], and Sir [[Magdi Yacoub]]. |

||

===Technology=== |

===Technology=== |

||

| Line 96: | Line 98: | ||

{{Main|Imhotep}} |

{{Main|Imhotep}} |

||

Considered to be the first engineer, architect and physician in history known by name, [[Imhotep]] designed the [[Pyramid of Djoser]] (the [[Step Pyramid]]) at [[Saqqara]] in [[History of ancient Egypt|Egypt]] around [[27th century BC|2630]]–[[27th century BC|2611 BC]], and may have been responsible for the first known use of [[columns]] in [[architecture]]. The Egyptian historian [[Manetho]] credited him with inventing stone-dressed |

Considered to be the first engineer, architect and physician in history known by name, [[Imhotep]] designed the [[Pyramid of Djoser]] (the [[Step Pyramid]]) at [[Saqqara]] in [[History of ancient Egypt|Egypt]] around [[27th century BC|2630]]–[[27th century BC|2611 BC]], and may have been responsible for the first known use of [[columns]] in [[architecture]]. The Egyptian historian [[Manetho]] credited him with inventing stone-dressed buildings during Djoser's reign, though he was not the first to actually build with stone. Imhotep is also believed to have founded [[Ancient Egyptian medicine|Egyptian medicine]], being the author of the world's earliest known medical document, the [[Edwin Smith Papyrus]]. |

||

===Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt=== |

===Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt=== |

||

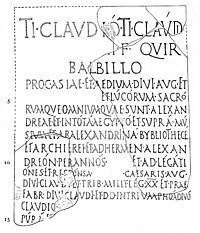

[[Image:Alexandria Library Inscription.jpg|thumb|200px|Inscription referring to the Alexandrian library, dated AD 56]] |

[[Image:Alexandria Library Inscription.jpg|thumb|200px|Inscription referring to the Alexandrian library, dated AD 56]] |

||

The silk |

The silk Road led straight through ancient Alexandria. Also, the [[Library of Alexandria|Royal Library of Alexandria]] was once the largest in the world. It is usually assumed to have been founded at the beginning of the 3rd century BC, during the reign of [[Ptolemy II of Egypt]] after his father had set up the [[Temple of the Muses]] or [[Museum]]. The initial organisation is attributed to [[Demetrius Phalereus]]. The library is estimated to have stored, at its peak, 400,000 to 700,000 [[Scroll (parchment)|scrolls]]. |

||

One of the reasons so little is known about the Library is that it was lost centuries after its creation. All that is left of many of the volumes are |

One of the reasons so little is known about the Library is that it was lost centuries after its creation. All that is left of many of the volumes are tantalising titles that hint at all the history lost due to the building's destruction. Few events in ancient history are as controversial as the destruction of the library, as the historical record is both contradictory and incomplete. Its destruction has been attributed by some authors to, among others, [[Julius Caesar]], [[Augustus]], and Catholic zealots during the purge of the Arian heresy. Not surprisingly, the Great Library became a symbol of knowledge itself, and its destruction was attributed to those who were portrayed as ignorant [[barbarians]], often for purely political reasons. |

||

A [[Bibliotheca Alexandrina|new library]] was inaugurated in 2003 near the site of the old library. |

A [[Bibliotheca Alexandrina|new library]] was inaugurated in 2003 near the site of the old library. |

||

The [[Lighthouse of Alexandria]], one of the [[Seven Wonders of the Ancient World]], designed by [[Sostratus of Cnidus]] and built during the reign of [[Ptolemy I Soter]] served as the city's landmark, and later, lighthouse. |

The [[Lighthouse of Alexandria]], one of the [[Seven Wonders of the Ancient World]], designed by [[Sostratus of Cnidus]] and built during the reign of [[Ptolemy I Soter]] served as the city's landmark, and, later, lighthouse. |

||

====Mathematics and technology==== |

====Mathematics and technology==== |

||

{{See also| |

{{See also|Ancient Egyptian mathematics}} |

||

[[Alexandria]], being the center of the Hellenistic world, produced a number of great mathematicians, astronomers, and scientists such as [[Ctesibius]], [[Pappus of Alexandria|Pappus]], and [[Diophantus]]. It also attracted scholars from all over the Mediterranean such as [[Eratosthenes]] of [[Cyrene, Libya|Cyrene]]. |

Since antiquity, Egypt has been producing many prominent mathematicians and thinkers. [[Alexandria]], being the center of the Hellenistic world, produced a number of great mathematicians, astronomers, and scientists, such as [[Hypatia]], [[Ctesibius]], [[Pappus of Alexandria|Pappus]], and [[Diophantus]]. It also attracted scholars from all over the Mediterranean, such as [[Eratosthenes]] of [[Cyrene, Libya|Cyrene]]. Ancient Egyptians were some of the first people to use mathematics, with the scribe [[Ahmes]] being the earliest known contributor to mathematics in history. Some of the greatest medieval mathematicians were Egyptians, such as [[Abu Kamil]] and [[Ibn Yunus]] whose works are noted for being ahead of their time, having been based on meticulous calculations and attention to detail. The crater [[Ibn Yunus (crater)|Ibn Yunus]] on the [[Moon]] is named after him.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ibn Yunus |url=http://wenamethestars.inkleby.com/feature/2635 |access-date=2023-10-17 |website=We Name The Stars |language=en}}</ref> |

||

====Ptolemy==== |

====Ptolemy==== |

||

| Line 119: | Line 121: | ||

[[Ptolemy]] is one of the most famous astronomers and geographers from Egypt, famous for his work in [[Alexandria]]. Born Claudius Ptolemaeus (Greek: Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαίος; c. 85 – c. 165), he was a [[geographer]], [[astronomer]], and [[astrologer]].<ref>Martin Bernal (1992). "Animadversions on the Origins of Western Science", ''Isis'' '''83''' (4), p. 596-607 [602, 606]</ref> |

[[Ptolemy]] is one of the most famous astronomers and geographers from Egypt, famous for his work in [[Alexandria]]. Born Claudius Ptolemaeus (Greek: Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαίος; c. 85 – c. 165), he was a [[geographer]], [[astronomer]], and [[astrologer]].<ref>Martin Bernal (1992). "Animadversions on the Origins of Western Science", ''Isis'' '''83''' (4), p. 596-607 [602, 606]</ref> |

||

Ptolemy was the author of two important scientific treatises. One is the astronomical treatise that is now known as the ''[[Almagest]]'' (in Greek ''Η μεγάλη Σύνταξις'', "The Great Treatise"). In this work, one of the most influential books of antiquity, Ptolemy compiled the astronomical knowledge of the ancient Greek and [[Babylonia]]n world. Ptolemy's other main work is his ''Geography''. This too is a compilation, |

Ptolemy was the author of two important scientific treatises. One is the astronomical treatise that is now known as the ''[[Almagest]]'' (in Greek ''Η μεγάλη Σύνταξις'', "The Great Treatise"). In this work, one of the most influential books of antiquity, Ptolemy compiled the astronomical knowledge of the ancient Greek and [[Babylonia]]n world. Ptolemy's other main work is his ''Geography''. This too is a compilation,of what was known about the world's [[geography]] in the Roman Empire in his time. |

||

In his ''[[Optics]]'', a work which survives only in an Arabic translation, he writes about properties of [[light]], including [[Reflection (physics)|reflection]], [[refraction]] and [[colour]]. His other works include ''Planetary Hypothesis'', ''Planisphaerium'' and ''Analemma''. Ptolemy's treatise on astrology, the ''[[Tetrabiblos]]'', was the most popular [[astrological]] work of antiquity and also enjoyed great influence in the [[Islamic]] world and the [[medieval]] [[Latin]] [[Western world|West]]. |

In his ''[[Optics]]'', a work which survives only in an Arabic translation, he writes about properties of [[light]], including [[Reflection (physics)|reflection]], [[refraction]] and [[colour]]. His other works include ''Planetary Hypothesis'', ''Planisphaerium'' and ''Analemma''. Ptolemy's treatise on astrology, the ''[[Tetrabiblos]]'', was the most popular [[astrological]] work of antiquity and also enjoyed great influence in the [[Islamic]] world and the [[medieval]] [[Latin]] [[Western world|West]]. |

||

| Line 126: | Line 128: | ||

Tributes to Ptolemy include Ptolemaeus crater on the Moon and Ptolemaeus crater on Mars. |

Tributes to Ptolemy include Ptolemaeus crater on the Moon and Ptolemaeus crater on Mars. |

||

'''Hypatia''' |

|||

{{Main|Hypatia}} |

|||

===Medieval Egypt=== |

===Medieval Egypt=== |

||

| Line 131: | Line 137: | ||

====Abu Kamil Shuja ibn Aslam==== |

====Abu Kamil Shuja ibn Aslam==== |

||

{{Main| |

{{Main|Abu Kamil}} |

||

[[Abu Kamil]] Shujāʿ ibn Aslam ibn Muḥammad Ibn Shujāʿ ([[Latinization (literature)|Latinized]] as '''Auoquamel''', [[Arabic language|Arabic]]: أبو كامل شجاع بن أسلم بن محمد بن شجاع, also known as '''''Al-ḥāsib al-miṣrī'''''—lit. "the Egyptian calculator") (c. 850 – c. 930) was a prominent [[Egyptians|Egyptian]] mathematician during the [[Islamic Golden Age]]. He is considered the first mathematician to systematically use and accept [[Irrational number|irrational numbers]] as solutions and [[coefficients]] to equations.<ref>{{Citation |last=Sesiano |first=Jacques |title=Islamic Mathematics |date=2000 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4301-1_9 |work=Mathematics Across Cultures |pages=137–165 |access-date=2023-10-17 |place=Dordrecht |publisher=Springer Netherlands |isbn=978-1-4020-0260-1}}</ref> His mathematical techniques were later adopted by [[Fibonacci]], thus allowing Abu Kamil an important part in introducing algebra to [[Europe]].<ref name=":0">{{Citation |last=Creighton |first=Ness |title=Abu, Kamil Shuja |date=2011-12-08 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.48128 |work=African American Studies Center |access-date=2023-10-17 |publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> |

|||

Abu Kamil made important contributions to [[algebra]] and [[geometry]]. He was the first [[Islamic mathematician]] to work easily with algebraic equations with powers higher than x<sup>2</sup> (up to the 8th power),<ref name=":0" /> and solved sets of non-linear [[simultaneous equations]] with three unknown [[Variable (mathematics)|variables]]. He illustrated the rules of signs for expanding the multiplication.<ref>{{Citation |last=Berggren |first=J. Lennart |title=Mathematics in Medieval Islam |date=2021-08-10 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1qgnq84.10 |work=The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam |pages=515–676 |access-date=2023-10-17 |publisher=Princeton University Press}}</ref> He wrote all problems rhetorically, and some of his books lacked any [[mathematical notation]] beside those of integers. For example, he uses the Arabic expression "māl māl shayʾ" ("square-square-thing") for x⁵. One notable feature of his works was enumerating all the possible solutions to a given equation.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=2000 |title=Linear and noncommutative algebra |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/dol/023/09 |journal=The Beginnings and Evolution of |

|||

Algebra |pages=149–160 |doi=10.1090/dol/023/09}}</ref> |

|||

The Muslim [[Encyclopédistes|encyclopedist]] [[Ibn Khaldūn]] classified Abū Kāmil as the second greatest algebraist chronologically after [[al-Khwarizmi]]. |

|||

====Ibn Yunus==== |

====Ibn Yunus==== |

||

| Line 145: | Line 158: | ||

In 1999, Zewail became the third Egyptian to receive the [[Nobel Prize]], following [[Anwar Sadat]] (1978 in Peace) and [[Naguib Mahfouz]] (1988 in Literature). In 1999, he received Egypt's highest state honor, the [[Grand Collar of the Nile]]. |

In 1999, Zewail became the third Egyptian to receive the [[Nobel Prize]], following [[Anwar Sadat]] (1978 in Peace) and [[Naguib Mahfouz]] (1988 in Literature). In 1999, he received Egypt's highest state honor, the [[Grand Collar of the Nile]]. |

||

'''Sameera Moussa''' |

|||

{{Main|Sameera Moussa}} |

|||

[[Sameera Moussa]] or Samira Musa Aly ([[Egyptian Arabic language|Egyptian Arabic]]: سميرة موسى) (March 3, 1917 – August 15, 1952) was the first female [[Egyptians|Egyptian]] [[Nuclear physics|nuclear physicist]].<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |date=2017-03-03 |title=Sameera Moussa |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/pt.5.031428 |journal=Physics Today |doi=10.1063/pt.5.031428 |issn=1945-0699}}</ref> Sameera held a doctorate in [[atomic radiation]]. She hoped her work would one day lead to affordable medical treatments and the peaceful use of atomic energy. She organized the Atomic Energy for Peace Conference and sponsored a call that set an international conference under the banner "[[Atoms for Peace]]." She was the first woman to work at [[Fuad I University|Cairo University]]. |

|||

Moussa believed in [[Atoms for Peace]]. She was known to say "My wish is for nuclear treatment of cancer to be as available and as cheap as [[Aspirin]]".<ref name=":1" /> She worked hard for this purpose and throughout her intensive research, she came up with a historic equation that would help break the atoms of cheap metals such as [[copper]], paving the way for a cheap nuclear bomb.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=2017-03-03 |title=Sameera Moussa |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/pt.5.031428 |journal=Physics Today |doi=10.1063/pt.5.031428 |issn=1945-0699}}</ref> |

|||

In recognition to her efforts, she was granted many awards.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=2017-03-03 |title=Sameera Moussa |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/pt.5.031428 |journal=Physics Today |doi=10.1063/pt.5.031428 |issn=1945-0699}}</ref> |

|||

'''Magdi Yacoub''' |

|||

{{Main|Magdi Yacoub}} |

|||

Sir [[Magdi Yacoub]] or Magdi Habib Yacoub [[Member of the Order of Merit|OM]] [[Fellow of the Royal Society|FRS]] ([[Arabic language|Arabic]]: د/مجدى حبيب يعقوب) (born 16 November 1935), is an [[Egyptians in the United Kingdom|Egyptian]] retired professor of [[cardiothoracic surgery]] at [[Imperial College London]], best known for his early work in [[Heart valve repair|repairing heart valves]] with surgeon [[Donald Ross (surgeon)|Donald Ross]], adapting the [[Ross procedure]], where the diseased [[aortic valve]] is replaced with the person's own [[pulmonary valve]], devising the [[arterial switch operation]] (ASO) in [[Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries|transposition of the great arteries]], and establishing the heart transplantation centre at [[Harefield Hospital]] in 1980 with a [[heart transplant]] for [[Derrick Morris]], who at the time of his death was Europe's longest-surviving heart transplant recipient. Yacoub subsequently performed the UK's first combined [[Heart–lung transplant|heart and lung transplant]] in 1983. |

|||

In 1995, Yacoub founded the charity Of Ahmed Sherif "Chain of Hope",<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kirby |first=Tony |date=2010-08 |title=ESC tackles child congenital heart disease in poor countries |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61236-6 |journal=The Lancet |volume=376 |issue=9740 |pages=501–502 |doi=10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61236-6 |issn=0140-6736}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |date=2009-01-29 |title=Lifetime Achievement Award shortlist: Professor Sir Magdi Habib Yacoub |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b282 |journal=BMJ |volume=338 |issue=jan29 1 |pages=b282–b282 |doi=10.1136/bmj.b282 |issn=0959-8138}}</ref> through which he continued to operate on children, and through which the provision of heart surgery for correctable heart defects are made possible in areas without specialist cardiac surgery units. He is also the head of the Magdi Yacoub Global Heart Foundation, co-founded with [[Ahmed Zewail]] and Ambassador [[Mohamed Shaker]] in 2008,<ref>{{Citation |title=Yacoub, Sir Magdi (Habib), (born 16 Nov. 1935), British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery, National Heart and Lung Institute (formerly Cardiothoracic Institute), Imperial College London (formerly British Postgraduate Medical Federation, University of London), since 1986; Director of Research, Magdi Yacoub Institute (formerly Harefield Research Foundation), Heart Science Centre |date=2007-12-01 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u41262 |work=Who's Who |access-date=2023-10-17 |publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> which launched the Aswan Heart project and founded the Aswan Heart Centre the following year.<ref>{{Citation |title=Yacoub, Sir Magdi (Habib), (born 16 Nov. 1935), British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery, National Heart and Lung Institute (formerly Cardiothoracic Institute), Imperial College London (formerly British Postgraduate Medical Federation, University of London), since 1986; Director of Research, Magdi Yacoub Institute (formerly Harefield Research Foundation), Heart Science Centre |date=2007-12-01 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u41262 |work=Who's Who |access-date=2023-10-17 |publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> |

|||

He retired from the National Health Service in 2001 at the age of 65. |

|||

====Egyptology==== |

====Egyptology==== |

||

{{Main|Egyptology}} |

{{Main|Egyptology}} |

||

In modern times, [[archaeology]] and the study of Egypt's ancient heritage as the field of [[Egyptology]] has become a major scientific pursuit in the country itself. The field began during the [[Middle Ages]], and has been led by Europeans and Westerners in modern times. The study of Egyptology, however, has in recent decades been taken up by Egyptian |

In modern times, [[archaeology]] and the study of Egypt's ancient heritage as the field of [[Egyptology]] has become a major scientific pursuit in the country itself. The field began during the [[Middle Ages]], and has been led by Europeans and Westerners in modern times. The study of Egyptology, however, has in recent decades been taken up by Egyptian archaeologists such as [[Zahi Hawass]] and the [[Supreme Council of Antiquities]] he leads. |

||

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone, a tablet written in ancient Greek, Egyptian [[Demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]] script, and Egyptian hieroglyphs, has partially been credited for the recent stir in the study of Ancient Egypt. [[Greek language|Greek]], a well-known language, gave linguists the ability to decipher the mysterious Egyptian hieroglyphic language. The ability to decipher hieroglyphics facilitated the translation of hundreds of the texts and inscriptions that were previously indecipherable, giving insight into Egyptian culture that would have otherwise been lost to the ages. The stone was discovered on July 15, 1799, in the port town of [[Rosetta]], Egypt, and has been held in the [[British Museum]] since 1802. |

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone, a tablet written in ancient Greek, Egyptian [[Demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]] script, and Egyptian hieroglyphs, has partially been credited for the recent stir in the study of Ancient Egypt. [[Greek language|Greek]], a well-known language, gave linguists the ability to decipher the mysterious Egyptian hieroglyphic language. The ability to decipher hieroglyphics facilitated the translation of hundreds of the texts and inscriptions that were previously indecipherable, giving insight into Egyptian culture that would have otherwise been lost to the ages. The stone was discovered on July 15, 1799, in the port town of [[Rosetta]], Egypt, and has been held in the [[British Museum]] since 1802. |

||

| Line 170: | Line 203: | ||

Local sports clubs receive financial support from the local governments, and many sporting clubs are financially and administratively supported by the government.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

Local sports clubs receive financial support from the local governments, and many sporting clubs are financially and administratively supported by the government.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

||

Some of the most well known Egyptian athletes include: [[Mohamed Salah]], [[Nour El Sherbini]], and [[Farida Osman]]. |

|||

==Media== |

==Media== |

||

| Line 180: | Line 215: | ||

The Egyptian film industry is the largest & most developed within Arabic-speaking cinema.<ref name="siscie"/> |

The Egyptian film industry is the largest & most developed within Arabic-speaking cinema.<ref name="siscie"/> |

||

The 'Golden Age' of Egyptian cinema is generally agreed to be between the 40's and the 60's, with some of the most notable films made being''[[The Night of Counting the Years|The Night of Counting The Years]]'', ''[[Aghla Min Hayati]]'', ''[[Cairo Station]],'' ''[[My Wife, the Director General]]'', ''[[Saladin the Victorious]]'', ''The Postman'', ''[[Back Again (film)|Back Again]]'', ''[[Soft Hands (film)|Soft Hands]]'', and ''[[The Land (1969 film)|The Land]].'' |

|||

Egypt has produced, and continues to produce, many great actors and actresses many of which have made it to Hollywood, such as [[Mena Massoud]] and [[Rami Malek]]. |

|||

'''Notable Egyptian Actresses''' |

|||

* [[Soad Hosny]] |

|||

* [[Faten Hamama]] |

|||

* [[Zubaida Tharwat]] |

|||

* [[Shadia]] |

|||

* [[Hind Rostom]] |

|||

* [[Lobna Abdel Aziz]] |

|||

* [[Nadia Lutfi]] |

|||

* [[Amina Rizk]] |

|||

* [[Shwikar]] |

|||

* [[Nelly Karim]] |

|||

* [[Yousra]] |

|||

* [[Mona Zaki]] |

|||

* [[Ghada Abdel Razek]] |

|||

* [[Donia Samir Ghanem]] and [[Amy Samir Ghanem]] |

|||

'''Notable Egyptian Actors''' |

|||

* [[Abdel Halim Hafez]] |

|||

* [[Rushdy Abaza]] |

|||

* [[Ahmed Ramzy]] |

|||

* [[Omar Sharif]] |

|||

* [[Ismail Yassine]] |

|||

* [[Farid al-Atrash]] |

|||

* [[Abdel Salam Al Nabulsy]] |

|||

* [[Ahmed Zaki (actor)]] |

|||

* [[Adel Emam]] |

|||

* [[Karim Abdel Aziz]] |

|||

* [[Mahmoud Abdel Aziz]] |

|||

* [[Samir Ghanem]] |

|||

* [[Ahmed Ezz (actor)]] |

|||

* [[Khaled El Nabawy]] |

|||

==Music== |

==Music== |

||

| Line 189: | Line 262: | ||

Contemporary [[Music of Egypt|Egyptian music]] traces its beginnings to the creative work of Abdu-l Hamuli, Almaz, Sayed Mikkawi, and Mahmud Osman, who were all patronized by [[Isma'il Pasha|Khedive Ismail]] and who influenced the later work of [[Sayed Darwish]], [[Umm Kulthum]], [[Mohammed Abdel Wahab]], [[Abdel Halim Hafez]] and other Egyptian musicians.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

Contemporary [[Music of Egypt|Egyptian music]] traces its beginnings to the creative work of Abdu-l Hamuli, Almaz, Sayed Mikkawi, and Mahmud Osman, who were all patronized by [[Isma'il Pasha|Khedive Ismail]] and who influenced the later work of [[Sayed Darwish]], [[Umm Kulthum]], [[Mohammed Abdel Wahab]], [[Abdel Halim Hafez]] and other Egyptian musicians.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

||

From the 1970s onwards, Egyptian [[pop music]] has become increasingly important in Egyptian culture, particularly among the large youth population of Egypt. Egyptian [[folk music]] is also popular, played during weddings and other festivities. In the last quarter of the 20th century, Egyptian music was a way to communicate [[social issue|social]] and [[social class|class]] issues. The most popular Egyptian pop singers are [[Amr Diab]], [[Tamer Hosny]], [[Mohamed Mounir]], [[Angham]] and [[Ali El Haggar]]. [[Electronic music]] composers, [[Halim El-Dabh]], is an Egyptian.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Writer |first=ByStaff |title=The Father of Electronic Music: A Brief History of Egyptian Composer Halim El Dabh |url=http://www.scenearabia.com/Noise/halim-el-dabh-egyptian-musician-composer-invented-electronic-music |access-date=2023-05-09 |website=SceneArabia}}</ref> |

From the 1970s onwards, Egyptian [[pop music]] has become increasingly important in Egyptian culture, particularly among the large youth population of Egypt. Egyptian [[folk music]] is also popular, played during weddings and other festivities. In the last quarter of the 20th century, Egyptian music was a way to communicate [[social issue|social]] and [[social class|class]] issues. The most popular Egyptian pop singers are [[Amr Diab]], [[Sherine]], [[Tamer Hosny]], [[Mohamed Mounir]], [[Angham]], [[Ruby (Egyptian singer)]] and [[Ali El Haggar]]. [[Electronic music]] composers, [[Halim El-Dabh]], is an Egyptian.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Writer |first=ByStaff |title=The Father of Electronic Music: A Brief History of Egyptian Composer Halim El Dabh |url=http://www.scenearabia.com/Noise/halim-el-dabh-egyptian-musician-composer-invented-electronic-music |access-date=2023-05-09 |website=SceneArabia}}</ref> |

||

[[Belly dance]], or ''Raqs Sharqi'' (literally: |

[[Belly dance]], or ''Raqs Sharqi'' (literally: Eastern Dance) originated in Egypt.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Birth of Modern Raqs Sharqi, Baladi and Ghawazee (Late 1800s to 1930s) and Belly Dance (5.2) |url=https://worlddanceheritage.org/birth-raqs-sharqi/ |access-date=2023-06-14 |website=World Dance Heritage}}</ref> [[Naima Akef]] was one of the most famous Egyptian bellydancers during the Egyptian Cinematic Golden Age. |

||

The Arabic musical discipline known as "maqam," or chanting has both secular and religious uses. Maqams are almost always sung by men in the region, where women who perform music or sing publicly are often viewed as promiscuous. The members of Alhour, Egypt's first all-female Muslim recitation choir, are challenging deep-rooted taboos about women singing in public or reciting from the Quran in the socially conservative country. Alhour choir was launched in 2017.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Egypt's First All-Women Islamic Choir Defies Gender Taboos|url=https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/egypt-islamic-women-choir/|access-date=2021-09-14|website=Global Citizen|language=en}}</ref> |

The Arabic musical discipline known as "maqam," or chanting has both secular and religious uses. Maqams are almost always sung by men in the region, where women who perform music or sing publicly are often viewed as promiscuous. The members of Alhour, Egypt's first all-female Muslim recitation choir, are challenging deep-rooted taboos about women singing in public or reciting from the Quran in the socially conservative country. Alhour choir was launched in 2017.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Egypt's First All-Women Islamic Choir Defies Gender Taboos|url=https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/egypt-islamic-women-choir/|access-date=2021-09-14|website=Global Citizen|language=en}}</ref> |

||

| Line 200: | Line 273: | ||

In 2012, Misr International Films was producing a television series based on the novel ''[[Zaat (novel)|Zaat]]'' by [[Sonallah Ibrahim]]. Filming of scenes set at [[Ain Shams University]] was scheduled to occur that year. However, [[Muslim Brotherhood]] student members and some teachers at the school protested, stating that the 1970s era clothing worn by the actresses was indecent and would not allow filming unless the clothing was changed. Gaby Khoury, the head of the film company, stated that the engineering department head, Sherif Hammad, "insisted that the filming should stop and that we would be reimbursed ... explaining that he was not able to guarantee the protection of the materials or the artists."<ref>"[https://www.dawn.com/news/694230/islamists-halt-filming-of-egyptian-tv-series Islamists halt filming of Egyptian TV series]." ''[[Daily News Egypt]]''. Thursday, February 9, 2012. [[NewsBank]] Record Number: 17587021. "[...]and teachers were against it, because of the clothing worn by the actresses," he said. The series, adapted from the novel "Zaat" by Egyptian author Sonallah Ibrahim, takes[...]"</ref> |

In 2012, Misr International Films was producing a television series based on the novel ''[[Zaat (novel)|Zaat]]'' by [[Sonallah Ibrahim]]. Filming of scenes set at [[Ain Shams University]] was scheduled to occur that year. However, [[Muslim Brotherhood]] student members and some teachers at the school protested, stating that the 1970s era clothing worn by the actresses was indecent and would not allow filming unless the clothing was changed. Gaby Khoury, the head of the film company, stated that the engineering department head, Sherif Hammad, "insisted that the filming should stop and that we would be reimbursed ... explaining that he was not able to guarantee the protection of the materials or the artists."<ref>"[https://www.dawn.com/news/694230/islamists-halt-filming-of-egyptian-tv-series Islamists halt filming of Egyptian TV series]." ''[[Daily News Egypt]]''. Thursday, February 9, 2012. [[NewsBank]] Record Number: 17587021. "[...]and teachers were against it, because of the clothing worn by the actresses," he said. The series, adapted from the novel "Zaat" by Egyptian author Sonallah Ibrahim, takes[...]"</ref> |

||

Nowadays, most Egyptians are free to wear whatever they want, depending on where they are. In more rural areas, though not limited to them, traditional clothes like the [[Jellabiya]],<ref>{{Citation |title=CLOTHING |date=2013-09-05 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781107325272.017 |work=The Arts and Crafts of Ancient Egypt |pages=147–151 |access-date=2023-10-17 |publisher=Cambridge University Press}}</ref> which is different from the Arabic [[Thawb|Thawb,]] and the [[Ammama]] are worn by men and the [[Abaya]] by women<ref>{{Cite web |title=Economics: Crafts |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1872-5309_ewic_ewiccom_0230 |access-date=2023-10-17 |website=Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures}}</ref> (usually accompanied by the [[Hijab]]). The traditional clothing, however, may vary depending on the region. Alexandrian, Sai'di, Nubian, Siwan, etc. Western clothes are commonplace. |

|||

==Cuisine== |

==Cuisine== |

||

{{Main|Egyptian cuisine}} |

{{Main|Egyptian cuisine}} |

||

Egyptian cuisine consists of local culinary traditions such as [[Ful medames]], [[Falafel]], [[Kushari]], and [[Molokhia]]. It also shares similarities with food found throughout the eastern Mediterranean like [[Kebab]] and [[Shawarma]]. |

Egyptian cuisine consists of local culinary traditions such as [[Ful medames]], [[Falafel]], [[Kushari]], [[Hawawshi]] and [[Molokhia]]. Other dishes include [[Dolma|Dolma,]] [[Samosa]], [[Lentil soup]], [[Taro|Qulqas soup]], and [[Bamia]] among many more. It also shares similarities with food found throughout the eastern Mediterranean like [[Kebab]] and [[Shawarma]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=historical dictionary of egypt |url=https://books.google.com.eg/books?id=QQNSAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA78&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=top 33 egyptian foods |url=https://doctorfithealth.com/blog/egyptian-food/}}</ref> |

||

Egyptians also enjoy a wide variety of desserts, such as [[Om Ali]]<ref>{{Cite web |title=umm ali recipe |url=https://www.allrecipes.com/recipe/73059/umm-ali/}}</ref> (which is the national dessert of Egypt), [[Basbousa]], [[Knafeh]], [[Qatayef]], [[Lokma]], [[Zalabiyeh]], [[Baklava]], and Meshabek. It is not uncommon to find bakeries in Egypt create their own desserts. |

|||

Tea and coffee are some of the mot popular drinks enjoyed in Egypt and are usually served in café-like shops called 'Ahwas (literally: coffee). Other drinks include [[Salep]], [[Karkade]], [[Anise|Yansoon]], [[Sugarcane juice]], [[Sobia (drink)]]<ref>{{Cite web |title=cracking coconut's history |url=https://www.aramcoworld.com/Articles/January-2017/Cracking-Coconut-s-History}}</ref> and [[Lemonade]]. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

{{Portal|Egypt}} |

{{Portal|Egypt}} |

||

* [[ |

* [[Egyptians]] |

||

* [[Bibliotheca Alexandrina]] |

* [[Bibliotheca Alexandrina]] |

||

* [[Center for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage]] |

* [[Center for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage]] |

||

| Line 216: | Line 295: | ||

* [[North Sinai Archaeological Sites Zone]] |

* [[North Sinai Archaeological Sites Zone]] |

||

* [[Shaware3na]] |

* [[Shaware3na]] |

||

* [[Egyptian Arabic]] |

|||

* [[Cinema of Egypt]] |

|||

* [[Music of Egypt]] |

|||

* [[Belly dance]] |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

| Line 223: | Line 306: | ||

* {{cite book|last=ʻAbd al-Ḥamīd Yūsuf|first=Ahmad|year=2003|title=From Pharaoh's lips: ancient Egyptian language in the Arabic of today|location=Minneapolis, Minn.|publisher=American University in Cairo Press|isbn=9789774247088|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UiybqmQYSoIC}} |

* {{cite book|last=ʻAbd al-Ḥamīd Yūsuf|first=Ahmad|year=2003|title=From Pharaoh's lips: ancient Egyptian language in the Arabic of today|location=Minneapolis, Minn.|publisher=American University in Cairo Press|isbn=9789774247088|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UiybqmQYSoIC}} |

||

* {{Cite book |last=Behrens-Abouseif |first=Doris |url=https://www.archnet.org/publications/3146 |title=Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction |publisher=E.J. Brill |year=1989 |isbn=9789004096264 |location=Leiden, the Netherlands |format=PDF}} |

* {{Cite book |last=Behrens-Abouseif |first=Doris |url=https://www.archnet.org/publications/3146 |title=Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction |publisher=E.J. Brill |year=1989 |isbn=9789004096264 |location=Leiden, the Netherlands |format=PDF}} |

||

==Further reading== |

|||

*{{Cite book |last=Asante |first=Molefi Kete |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=COTEEAAAQBAJ |title=Culture and Customs of Egypt |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2002 |isbn=0313317402 |location= |pages= |language=en}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 22:11, 17 October 2023

| This article is part of a series on |

| Life in Egypt |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Society |

| Politics |

| Economy |

|

Egypt portal |

The culture of Egypt has thousands of years of recorded history. Ancient Egypt was among the earliest civilizations in the world. For millennia, Egypt developed strikingly unique, complex, and stable cultures that influenced other cultures of Europe, Africa and the Middle East.[1]

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2023) |

Languages

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

Arabic is currently Egypt's official language. It came to Egypt in the 7th century,[2] and it is the formal and official language of the state which is used by the government and newspapers. Meanwhile, the Egyptian Arabic dialect, or Masri is the official spoken language of the people. Of the many varieties of Arabic, the Egyptian dialect is the most widely spoken and the most understood, due to the great influence of Egyptian cinema and the Egyptian media throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Today, many foreign students tend to learn it through Egyptian songs and movies, and the dialect is usually labelled by the general public as one of the easiest and fastest to learn, mainly due to the huge amount of accessible sources (movies, series, TV shows, books, etc.) that contribute to its learning process.[citation needed] Egypt's position in the heart of the Arabic-speaking world has made it the centre of culture, and its widespread dialect has had a huge influence on almost all neighbouring dialects, having so many Egyptian sayings in their daily lives. [citation needed]

The Egyptian language, which formed a separate branch among the family of Afro-Asiatic languages, was among the first written languages and is known from the hieroglyphic inscriptions preserved on monuments and sheets of papyrus. The Coptic language, the most recent stage of Egyptian written in mainly Greek alphabet with seven demotic letters, is today the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church.[citation needed]

The "Koiné" dialect of the Greek language was important in Hellenistic Alexandria, was used in the philosophy and science of that culture, and was later studied by Arabic scholars.[citation needed]

In the upper Nile Valley, southern Egypt, around Kom Ombo and south of Aswan, there are about 300,000 speakers of Nubian languages; mainly Noubi, but also Kenuzi-Dongola. In Siwa Oasis, there is also the Siwi language that is spoken by about 20,000 speakers. Other minorities include roughly two thousand Greek speakers in Alexandria and Cairo as well as roughly 5,000 Armenian speakers.[citation needed]

Literature

Many Egyptians believed that when it came to a death of their Pharaoh, they would have to bury the Pharaoh deep inside the Pyramid. The ancient Egyptian literature dates back to the Old Kingdom, in the third millennium BC. Religious literature is best known for its hymns to and its mortuary texts. The oldest extant Egyptian literature is the Pyramid Texts: the mythology and rituals carved around the tombs of rulers. The later, secular literature of ancient Egypt includes the "wisdom texts", forms of philosophical instruction. The Instruction of Ptahhotep, for example, is a collation of moral proverbs by an Egto (the middle of the second millennium BC) seem to have been drawn from an elite administrative calss, and were celebrated and revered into the New Kingdom (to the end of the second millennium). In time, the Pyramid Texts became Coffin Texts (perhaps after the end of the Old Kingdom), and finally, the mortuary literature produced its masterpiece, the Book of the Dead, during the New Kingdom.[citation needed]

The Middle Kingdom was the golden age of Egyptian literature. Some texts include the Tale of Neferty, the Instructions of Amenemhat I, the Tale of Sinuhe, the Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor and the Story of the Eloquent Peasant. Instructions became a popular literary genre of the New Kingdom, taking the form of advice on proper behavioru. The Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any are examples from this period.[citation needed]

During the Greco-Roman period (332 BC − AD 639), Egyptian literature was translated into other languages, and Greco-Roman literature fused with native art into a new style of writing. From this period comes the Rosetta Stone, which became the key to unlocking the mysteries of Egyptian writing for modern scholarship. The city of Alexandria boasted its Library of almost half a million handwritten books during the third century BC. Alexandria's center of learning also produced the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint.

During the first few centuries of the Christian era, Egypt was a source of a great deal of ascetic literature in the Coptic language. Egyptian monasteries translated many Greek and Syriac words, which are now only extant in Coptic. Under Islam, Egypt continued to be a great source of literary endeavour, now in the Arabic language. In 970, al-Azhar University was founded in Cairo, which to this day remains the most important center of Sunni Islamic learning. In 12th-century Egypt, the Jewish Talmudic scholar Maimonides produced his most important work.

In contemporary times, Egyptian novelists and poets were among the first to experiment with modern styles of Arabic-language literature, and the forms they developed have been widely imitated. The first modern Egyptian novel Zaynab by Muhammad Husayn Haykal was published in 1913 in the Egyptian vernacular. Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz was the first Arabic-language writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Many Egyptian books and films are available throughout the Middle East. Other Egyptian writers include Nawal El Saadawi, known for her feminist works and activism, and Alifa Rifaat who also wrote about women and tradition. Vernacular poetry is said to be the most popular literary genre amongst Egyptians, represented by Bayram el-Tunsi, Ahmed Fouad Negm (Fagumi), Salah Jaheen and Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi.

Religion

About 85–95% of Egypt's population is Muslim, with a Sunni majority. About 5- 15% of the population is Coptic Christian; other religions and other forms of Christianity comprise the remaining three percent.[3] Sunni Islam sees Egypt as an important part of its religion due to not only Quranic verses mentioning the country but also due to the Al-Azhar University, one of the earliest of the world universities. It was created as a school for religious studies and works.[citation needed]

Visual art

Egyptian art in antiquity

The Egyptians were one of the first major civilizations to codify design elements in art. The wall painting done in the service of the Pharaohs followed a rigid code of visual rules and meanings. Early Egyptian art is characterised by the absence of linear perspective, which results in a seemingly flat space. These artists tended to create images based on what they knew and not as much on what they saw. Objects in these artworks generally do not decrease in size as they increase in distance, and there is little shading to indicate depth. Sometimes, distance is indicated through the use of tiered space, where more distant objects are drawn higher above the nearby objects, but in the same scale and with no overlapping of forms. People and objects are almost always drawn in profile.

Painting achieved its greatest height in Dynasty XVII during the reigns of Tuthmose IV and Amenhotep III. The Frfgmentary panel of the Lady Thepu, on the right, dates from the time of the latter king.[4]

Early Egyptian artists did have a system for maintaining dimensions within artwork. They used a grid system that allowed them to create a smaller version of the artwork and then scale up the design based on proportional representation on a larger grid.

Egyptian art in modern times

Modern and contemporary Egyptian art can be as diverse as any works in the world art scene. Some well-known names include Mahmoud Mokhtar, Abdel Hadi Al Gazzar, Farouk Hosny, Gazbia Sirry, Kamal Amin, Hussein El Gebaly, Sawsan Amer and many others. Many artists in Egypt have taken on modern media such as digital art and this has been the theme of many exhibitions in Cairo in recent times. There has also been a tendency to use the World Wide Web as an alternative outlet for artists and there are strong Art-focused internet community groups that have found their origins in Egypt.

Architecture

There have been many architectural styles used in Egyptian buildings over the centuries, including Ancient Egyptian architecture, Greco-Roman architecture, Islamic architecture, and modern architecture.

Ancient Egyptian architecture is best known for its monumental temples and tombs built in stone, including its famous pyramids, such as the pyramids of Giza. These were built with a distinctive repertoire of elements including pylon gateways, hypostyle halls, obelisks, and hieroglyphic decoration. The advent of Greek Ptolemaic rule, followed by Roman rule, introduced elements of Greco-Roman architecture into Egypt, especially in the capital city of Alexandria. After this came Coptic architecture, including early Christian architecture, which continued to follow ancient classical and Byzantine influences.

Following the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th century, Islamic architecture flourished. A new capital, Fustat, was founded; it became the center of monumental architectural patronage thenceforth, and through successive new administrative capitals, it eventually became the modern city of Cairo. Early Islamic architecture displayed a mix of influences, including classical antiquity and new influences from the east such as the Abbasid style that radiated from the Abbasid Caliphate's heartland in Mesopotomia (present-day Iraq) during the 9th century. In the 10th century, Egypt became the center of a new empire, the Fatimid Caliphate. Fatimid architecture initiated further developments that influenced the architectural styles of subsequent periods. Saladin, who overthrew the Fatimids and founded the Ayyubid dynasty in the 12th century, was responsible for constructing the Cairo Citadel, which remained the center of government until the 19th century. During the Mamluk period (13th–16th centuries), a wealth of monumental religious and funerary complexes were built, constituting much of Cairo's medieval heritage today. The Mamluk architectural style continued to linger even after the Ottoman conquest of 1517, when Egypt became an Ottoman province.

In the early 19th century, Muhammad Ali began to modernize Egyptian society and encouraged a break with traditional medieval architectural traditions, initially by emulating late Ottoman architectural trends. Under the reign of his grandson Isma'il Pasha (1860s and 1870s), reform efforts were pushed further, the Suez Canal was constructed (inaugurated in 1869), and a new Haussmann-influenced expansion of Cairo began. European tastes became strongly evident in architecture in the late 19th century, though there was also a trend of reviving what were seen as indigenous or "national" architectural styles, such as the many Neo-Mamluk buildings of this era. In the 20th century, some Egyptian architects pushed back against dominant Western ideas of architecture. Among them, Hassan Fathy was known for adapting indigenous vernacular architecture to modern needs. Since then, Egypt continues to see new buildings erected in a variety of styles and for various purposes, ranging from housing projects to more monumental prestige projects like the Cairo Tower (1961) and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina (2002).Science

Egypt's cultural contributions have included great works of science, art, and mathematics, dating from antiquity to modern times. Egypt has produced many brilliant scientists, the most famous of them being Ahmed Zewail, Sameera Moussa, and Sir Magdi Yacoub.

Technology

Imhotep

Considered to be the first engineer, architect and physician in history known by name, Imhotep designed the Pyramid of Djoser (the Step Pyramid) at Saqqara in Egypt around 2630–2611 BC, and may have been responsible for the first known use of columns in architecture. The Egyptian historian Manetho credited him with inventing stone-dressed buildings during Djoser's reign, though he was not the first to actually build with stone. Imhotep is also believed to have founded Egyptian medicine, being the author of the world's earliest known medical document, the Edwin Smith Papyrus.

Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt

The silk Road led straight through ancient Alexandria. Also, the Royal Library of Alexandria was once the largest in the world. It is usually assumed to have been founded at the beginning of the 3rd century BC, during the reign of Ptolemy II of Egypt after his father had set up the Temple of the Muses or Museum. The initial organisation is attributed to Demetrius Phalereus. The library is estimated to have stored, at its peak, 400,000 to 700,000 scrolls.

One of the reasons so little is known about the Library is that it was lost centuries after its creation. All that is left of many of the volumes are tantalising titles that hint at all the history lost due to the building's destruction. Few events in ancient history are as controversial as the destruction of the library, as the historical record is both contradictory and incomplete. Its destruction has been attributed by some authors to, among others, Julius Caesar, Augustus, and Catholic zealots during the purge of the Arian heresy. Not surprisingly, the Great Library became a symbol of knowledge itself, and its destruction was attributed to those who were portrayed as ignorant barbarians, often for purely political reasons.

A new library was inaugurated in 2003 near the site of the old library.

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, designed by Sostratus of Cnidus and built during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter served as the city's landmark, and, later, lighthouse.

Mathematics and technology

Since antiquity, Egypt has been producing many prominent mathematicians and thinkers. Alexandria, being the center of the Hellenistic world, produced a number of great mathematicians, astronomers, and scientists, such as Hypatia, Ctesibius, Pappus, and Diophantus. It also attracted scholars from all over the Mediterranean, such as Eratosthenes of Cyrene. Ancient Egyptians were some of the first people to use mathematics, with the scribe Ahmes being the earliest known contributor to mathematics in history. Some of the greatest medieval mathematicians were Egyptians, such as Abu Kamil and Ibn Yunus whose works are noted for being ahead of their time, having been based on meticulous calculations and attention to detail. The crater Ibn Yunus on the Moon is named after him.[6]

Ptolemy

Ptolemy is one of the most famous astronomers and geographers from Egypt, famous for his work in Alexandria. Born Claudius Ptolemaeus (Greek: Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαίος; c. 85 – c. 165), he was a geographer, astronomer, and astrologer.[7]

Ptolemy was the author of two important scientific treatises. One is the astronomical treatise that is now known as the Almagest (in Greek Η μεγάλη Σύνταξις, "The Great Treatise"). In this work, one of the most influential books of antiquity, Ptolemy compiled the astronomical knowledge of the ancient Greek and Babylonian world. Ptolemy's other main work is his Geography. This too is a compilation,of what was known about the world's geography in the Roman Empire in his time.

In his Optics, a work which survives only in an Arabic translation, he writes about properties of light, including reflection, refraction and colour. His other works include Planetary Hypothesis, Planisphaerium and Analemma. Ptolemy's treatise on astrology, the Tetrabiblos, was the most popular astrological work of antiquity and also enjoyed great influence in the Islamic world and the medieval Latin West.

Ptolemy also wrote influential work Harmonics on music theory. After criticizing the approaches of his predecessors, Ptolemy argued for basing musical intervals on mathematical ratios (in contrast to the followers of Aristoxenus) backed up by empirical observation (in contrast to the over-theoretical approach of the Pythagoreans). He presented his own divisions of the tetrachord and the octave, which he derived with the help of a monochord. Ptolemy's astronomical interests appeared in a discussion of the music of the spheres.

Tributes to Ptolemy include Ptolemaeus crater on the Moon and Ptolemaeus crater on Mars.

Hypatia

Medieval Egypt

Abu Kamil Shuja ibn Aslam

Abu Kamil Shujāʿ ibn Aslam ibn Muḥammad Ibn Shujāʿ (Latinized as Auoquamel, Arabic: أبو كامل شجاع بن أسلم بن محمد بن شجاع, also known as Al-ḥāsib al-miṣrī—lit. "the Egyptian calculator") (c. 850 – c. 930) was a prominent Egyptian mathematician during the Islamic Golden Age. He is considered the first mathematician to systematically use and accept irrational numbers as solutions and coefficients to equations.[8] His mathematical techniques were later adopted by Fibonacci, thus allowing Abu Kamil an important part in introducing algebra to Europe.[9]

Abu Kamil made important contributions to algebra and geometry. He was the first Islamic mathematician to work easily with algebraic equations with powers higher than x2 (up to the 8th power),[9] and solved sets of non-linear simultaneous equations with three unknown variables. He illustrated the rules of signs for expanding the multiplication.[10] He wrote all problems rhetorically, and some of his books lacked any mathematical notation beside those of integers. For example, he uses the Arabic expression "māl māl shayʾ" ("square-square-thing") for x⁵. One notable feature of his works was enumerating all the possible solutions to a given equation.[11]

The Muslim encyclopedist Ibn Khaldūn classified Abū Kāmil as the second greatest algebraist chronologically after al-Khwarizmi.

Ibn Yunus

Modern Egypt

Ahmed Zewail

Ahmed Zewail (Template:Lang-ar) (born February 26, 1946) is an Egyptian chemist, and the winner of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on femtochemistry. Born in Damanhur (60 km south-east of Alexandria) and raised in Disuq, he moved to the United States to complete his PhD at the University of Pennsylvania. He was awarded a faculty appointment at Caltech in 1976, where he has remained since.

Zewail's key work has been as the pioneer of femtochemistry. He developed a method using a rapid laser technique (consisting of ultrashort laser flashes), which allows the description of reactions at the atomic level. It can be viewed as a highly sophisticated form of flash photography

In 1999, Zewail became the third Egyptian to receive the Nobel Prize, following Anwar Sadat (1978 in Peace) and Naguib Mahfouz (1988 in Literature). In 1999, he received Egypt's highest state honor, the Grand Collar of the Nile.

Sameera Moussa

Sameera Moussa or Samira Musa Aly (Egyptian Arabic: سميرة موسى) (March 3, 1917 – August 15, 1952) was the first female Egyptian nuclear physicist.[12] Sameera held a doctorate in atomic radiation. She hoped her work would one day lead to affordable medical treatments and the peaceful use of atomic energy. She organized the Atomic Energy for Peace Conference and sponsored a call that set an international conference under the banner "Atoms for Peace." She was the first woman to work at Cairo University.

Moussa believed in Atoms for Peace. She was known to say "My wish is for nuclear treatment of cancer to be as available and as cheap as Aspirin".[12] She worked hard for this purpose and throughout her intensive research, she came up with a historic equation that would help break the atoms of cheap metals such as copper, paving the way for a cheap nuclear bomb.[13]

In recognition to her efforts, she was granted many awards.[14]

Magdi Yacoub

Sir Magdi Yacoub or Magdi Habib Yacoub OM FRS (Arabic: د/مجدى حبيب يعقوب) (born 16 November 1935), is an Egyptian retired professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Imperial College London, best known for his early work in repairing heart valves with surgeon Donald Ross, adapting the Ross procedure, where the diseased aortic valve is replaced with the person's own pulmonary valve, devising the arterial switch operation (ASO) in transposition of the great arteries, and establishing the heart transplantation centre at Harefield Hospital in 1980 with a heart transplant for Derrick Morris, who at the time of his death was Europe's longest-surviving heart transplant recipient. Yacoub subsequently performed the UK's first combined heart and lung transplant in 1983.

In 1995, Yacoub founded the charity Of Ahmed Sherif "Chain of Hope",[15][16] through which he continued to operate on children, and through which the provision of heart surgery for correctable heart defects are made possible in areas without specialist cardiac surgery units. He is also the head of the Magdi Yacoub Global Heart Foundation, co-founded with Ahmed Zewail and Ambassador Mohamed Shaker in 2008,[17] which launched the Aswan Heart project and founded the Aswan Heart Centre the following year.[18]

He retired from the National Health Service in 2001 at the age of 65.

Egyptology

In modern times, archaeology and the study of Egypt's ancient heritage as the field of Egyptology has become a major scientific pursuit in the country itself. The field began during the Middle Ages, and has been led by Europeans and Westerners in modern times. The study of Egyptology, however, has in recent decades been taken up by Egyptian archaeologists such as Zahi Hawass and the Supreme Council of Antiquities he leads.

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone, a tablet written in ancient Greek, Egyptian Demotic script, and Egyptian hieroglyphs, has partially been credited for the recent stir in the study of Ancient Egypt. Greek, a well-known language, gave linguists the ability to decipher the mysterious Egyptian hieroglyphic language. The ability to decipher hieroglyphics facilitated the translation of hundreds of the texts and inscriptions that were previously indecipherable, giving insight into Egyptian culture that would have otherwise been lost to the ages. The stone was discovered on July 15, 1799, in the port town of Rosetta, Egypt, and has been held in the British Museum since 1802.

Sport

Football is the most popular sport in Egypt. Egyptian football clubs, especially Al Ahly, with 118 trophies in total and Zamalek are known throughout Africa.[citation needed] The Egyptian national football team won the African Cup of Nations a record 7 times (in 1957, 1959, 1986, 1998, 2006 (on home soil), 2008 and 2010). Egypt was the first African country to join FIFA, but it has only made it to the FIFA World Cup three times, in 1934, 1990 and 2018. Egypt also won the World Military Cup five times and finished as runners-up twice.[citation needed]

Other popular sports in Egypt are basketball, handball, squash, and tennis.[citation needed]

The Egyptian national basketball team holds the record for best performance at the Basketball World Cup and at the Summer Olympics in Middle East and Africa.[19][20] Egypt hosted the 2017 FIBA Under-19 Basketball World Cup and is the only African country to host an official basketball world cup at junior or senior level.[citation needed] Further, the country hosted the official African Basketball Championship on six occasions. Egypt also hosted multiple continental youth championships including the 2020 FIBA Africa Under-18 Championship and the 2020 FIBA Africa Under-18 Championship for Women.[21] The Pharaohs, as they are commonly known, won 16 medals at the African Championship.[citation needed]