Tell al-Rimah: Difference between revisions

Ploversegg (talk | contribs) →History: detail w/ref |

Ploversegg (talk | contribs) →Archaeology: detail w/ref |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

A number of [[Akkadian language|Old Babylonian]] tablets contemporary with [[Zimri-Lim]] of [[Mari, Syria|Mari]] and 40 tablets from the time of [[Shalmaneser I]] were found as well as other objects. The tablets are mostly administrative documents involving loans of grain or tin.<ref>H. W. F. Saggs, The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1965, Iraq, vol. 30, vo. 2, pp. 154-174, 1968</ref><ref>D. J. Wiseman, The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1966, Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 175-205, 1968</ref><ref>Stephanie Page, The Tablets from Tell Al-Rimah 1967: A Preliminary Report, Iraq, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 87-97, 1968</ref> The tablets also showed a thriving wine industry.<ref>McGovern, Patrick E., "Wine and the Great Empires of the Ancient Near East", Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 167-209, 2019</ref> A god, [[Saggar (god)|Saggar]], known from [[Mari, Syria|Mari]] is also attested in the texts.<ref>Archi, Alfonso, "Studies in the Pantheon of Ebla", Ebla and Its Archives: Texts, History, and Society, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 592-600, 2015</ref> |

A number of [[Akkadian language|Old Babylonian]] tablets contemporary with [[Zimri-Lim]] of [[Mari, Syria|Mari]] and 40 tablets from the time of [[Shalmaneser I]] were found as well as other objects. The tablets are mostly administrative documents involving loans of grain or tin.<ref>H. W. F. Saggs, The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1965, Iraq, vol. 30, vo. 2, pp. 154-174, 1968</ref><ref>D. J. Wiseman, The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1966, Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 175-205, 1968</ref><ref>Stephanie Page, The Tablets from Tell Al-Rimah 1967: A Preliminary Report, Iraq, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 87-97, 1968</ref> The tablets also showed a thriving wine industry.<ref>McGovern, Patrick E., "Wine and the Great Empires of the Ancient Near East", Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 167-209, 2019</ref> A god, [[Saggar (god)|Saggar]], known from [[Mari, Syria|Mari]] is also attested in the texts.<ref>Archi, Alfonso, "Studies in the Pantheon of Ebla", Ebla and Its Archives: Texts, History, and Society, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 592-600, 2015</ref> |

||

The most notable artifact found was the stele of [[Adad-nirari III]] (811 to 783 BC), known as the [[Tell al-Rimah stela]], |

The most notable artifact found was the stele of [[Adad-nirari III]] (811 to 783 BC), known as the [[Tell al-Rimah stela]], which may mention an early king of [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Northern Israel]] stating "He received the tribute of Ia'asu the Samaritan, of the Tyrian (ruler) and of the Sidonian (ruler)" and contains the first cuneiform mention of [[Samaria]] by that name. On the side of the stele was an inscription of Nergal-ereš, who names himself "governor of Raṣappa".<ref>Page, Stephanie, "A Stela of Adad-Nirari III and Nergal-Ereš from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 139–53, 1968</ref><ref>Shea, William H., "Adad-Nirari III and Jehoash of Israel", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 101–13, 1978</ref><ref>Parpola, Simo, "The Location of Raṣappa", At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate, edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 393-412, 2017</ref> It has been suggested, based on the stele, that Tell al-Rimah has called Zamaḫâ at that time.<ref>May, Natalie N., "“The True Image of the God…:” Adoration of the King’s Image, Assyrian Imperial Cult and Territorial Control", Tales of Royalty: Notions of Kingship in Visual and Textual Narration in the Ancient Near East, edited by Elisabeth Wagner-Durand and Julia Linke, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 185-240, 2020</ref> A larger version of this stele was found at [[Dūr-Katlimmu]].<ref>Radner, Karen, "The Stele of Adad-nērārī III and Nergal-ēreš from Dūr-Katlimmu (Tell Šaiḫ Ḥamad)", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 265-277, 2012</ref> |

||

Old Babylonian period seal was found saying "i-lí-sa-ma-[ás] dumu iq-qa-at utu/iskur ir pí-it-ha-na" ie Ill-Samas, son of Iqqāt-Šamas/Addu, servant of Pithana" which has given rise to the suggestion that this referred to [[Pithana]] who was ruler of the Anatolian city of [[Kuššara]].<ref>Lacambre, Denis, and Werner Nahm, "Pithana, an Anatolian Ruler in the Time of Samsuiluna of Babylon: New Data From Tell Rimah (Iraq)", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 109, pp. 17–28, 2015</ref> |

|||

Among the finds were over 40 Middle Assyrian period [[faience]] rosettes with "transverse perforations on the reverse sides and a knob disc attached to their obverse sides".<ref>Puljiz, Ivana, "Faience for the empire: A Study of Standardized Production in the Middle Assyrian State", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 100-122, 2021</ref> |

Among the finds were over 40 Middle Assyrian period [[faience]] rosettes with "transverse perforations on the reverse sides and a knob disc attached to their obverse sides".<ref>Puljiz, Ivana, "Faience for the empire: A Study of Standardized Production in the Middle Assyrian State", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 100-122, 2021</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:48, 23 November 2023

Qattara/Karana (?) | |

| Location | Nineveh Province, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 36°15′25.51″N 42°26′57.61″E / 36.2570861°N 42.4493361°E |

| Type | tell |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1964–1971 |

| Archaeologists | D. Oates |

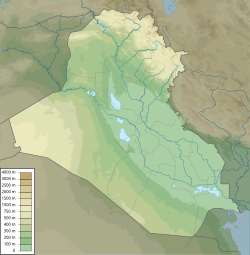

Tell al-Rimah is a tell, or archaeological settlement mound, in Nineveh Province (Iraq) roughly 80 kilometres (50 mi) west of Mosul and ancient Nineveh in the Sinjar region. It lies 15 kilometers south of the site of Tal Afar. Its ancient name may have been either Karana or Qattara, though the later name is now less favored.

Archaeology

The site covers an area roughly 500 meters by 500 meters, surrounded by a polygonal city wall. The interior holds a number of low mounds and a large central mound 30 meters high and 100 meters in diameter.[1]

The region was originally surveyed by Seton Lloyd in 1938.[2] The site of Tell al-Rimah was excavated from 1964 to 1971 by a British School of Archaeology in Iraq team led by David Oates, joined by the Penn Museum and Theresa Howard Carter in the first three years.[3][4][5][6][7][8] A large temple and palace from the early second millennium BC were excavated, as well as a Neo-Assyrian building. Tell al-Rimah also is known for having a third millennium example of brick vaulting.[9]

A number of Old Babylonian tablets contemporary with Zimri-Lim of Mari and 40 tablets from the time of Shalmaneser I were found as well as other objects. The tablets are mostly administrative documents involving loans of grain or tin.[10][11][12] The tablets also showed a thriving wine industry.[13] A god, Saggar, known from Mari is also attested in the texts.[14]

The most notable artifact found was the stele of Adad-nirari III (811 to 783 BC), known as the Tell al-Rimah stela, which may mention an early king of Northern Israel stating "He received the tribute of Ia'asu the Samaritan, of the Tyrian (ruler) and of the Sidonian (ruler)" and contains the first cuneiform mention of Samaria by that name. On the side of the stele was an inscription of Nergal-ereš, who names himself "governor of Raṣappa".[15][16][17] It has been suggested, based on the stele, that Tell al-Rimah has called Zamaḫâ at that time.[18] A larger version of this stele was found at Dūr-Katlimmu.[19]

Old Babylonian period seal was found saying "i-lí-sa-ma-[ás] dumu iq-qa-at utu/iskur ir pí-it-ha-na" ie Ill-Samas, son of Iqqāt-Šamas/Addu, servant of Pithana" which has given rise to the suggestion that this referred to Pithana who was ruler of the Anatolian city of Kuššara.[20]

Among the finds were over 40 Middle Assyrian period faience rosettes with "transverse perforations on the reverse sides and a knob disc attached to their obverse sides".[21]

History

While it appears that the site was occupied in the third millennium BCE, it reached its greatest size and prominence during the second millennium BCE and in the Neo-Assyrian period. The second millennium activity was primarily during the Old Babylonian and Mitanni periods. In the Middle Bronze period the site experienced widespread destruction and was abandoned before being re-occupied in the Late Bronze period. At various times, Tell al-Rimah has been linked with either Qatara or Karana, both cites known to be in that area during the second millennium. A notable find was a large archive of letters of Iltani, daughter of Samu-Addu, king of Karana.[22][23] Her husband was Aqba-aḫum of Qaṭṭara who in a text found at Mari wrote to her saying "The ice (house) of Qaṭṭara should be unsealed, so that the goddess, you, and Belassunu could drink from it as needed. But the ice must remain under guard.".[24] Another Mari text involving Iltani reveals that there was a version of he goddess Istar at Qatara.

"1 goat, offerin of Iltani to Išḫara of Aritanaya; 1 goat offering of Iltani to Ištar of Ninet (Nineveh); 1 spring lamb, offering of Iltani to Ištar of Qaṭṭara, when she dedicated (a votive) statue of Yadruk-Addu; 1 lamb, offering of Iltani to Sin [8.x*.Ṣabrum]."[25]

Gallery

-

Stele of Adad-nirari III from Tell al Rimah, discovered in 1967, now in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad

-

Marble column from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq, Neo-Assyrian period. Iraq Museum

-

Limestone relief of a male figure from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq. Kassite period. Iraq Museum

See also

References

- ^ [1]David Oates, "Excavations at Tell al Rimah A Summary Report", Sumer, vol. 19, no. 1-2, pp. 69-78, 1963

- ^ Seton Lloyd, Some Ancient Sites in the Sinjar district, Iraq, vol. 5, pp. 123ff, 1938

- ^ David Oates, The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: 1964, Iraq, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 62-68, 1965

- ^ David Oates, The Excavations at Tell al Rimah, 1965, Iraq, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 122-139, 1966

- ^ David Oates, The Excavations at Tell al Rimah, 1966, Iraq, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 70-96, 1967

- ^ David Oates, The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: 1967, Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 115-138, 1968

- ^ David Oates, The Excavations at Tell al Rimah, 1968, Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 1-26, 1970

- ^ David Oates, The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: 1971, Iraq, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 77-86, 1972

- ^ Barbara Parker, Cylinder Seals from Tell al Rimah, Iraq, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 21-38, 1975

- ^ H. W. F. Saggs, The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1965, Iraq, vol. 30, vo. 2, pp. 154-174, 1968

- ^ D. J. Wiseman, The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1966, Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 175-205, 1968

- ^ Stephanie Page, The Tablets from Tell Al-Rimah 1967: A Preliminary Report, Iraq, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 87-97, 1968

- ^ McGovern, Patrick E., "Wine and the Great Empires of the Ancient Near East", Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 167-209, 2019

- ^ Archi, Alfonso, "Studies in the Pantheon of Ebla", Ebla and Its Archives: Texts, History, and Society, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 592-600, 2015

- ^ Page, Stephanie, "A Stela of Adad-Nirari III and Nergal-Ereš from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 139–53, 1968

- ^ Shea, William H., "Adad-Nirari III and Jehoash of Israel", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 101–13, 1978

- ^ Parpola, Simo, "The Location of Raṣappa", At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate, edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 393-412, 2017

- ^ May, Natalie N., "“The True Image of the God…:” Adoration of the King’s Image, Assyrian Imperial Cult and Territorial Control", Tales of Royalty: Notions of Kingship in Visual and Textual Narration in the Ancient Near East, edited by Elisabeth Wagner-Durand and Julia Linke, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 185-240, 2020

- ^ Radner, Karen, "The Stele of Adad-nērārī III and Nergal-ēreš from Dūr-Katlimmu (Tell Šaiḫ Ḥamad)", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 265-277, 2012

- ^ Lacambre, Denis, and Werner Nahm, "Pithana, an Anatolian Ruler in the Time of Samsuiluna of Babylon: New Data From Tell Rimah (Iraq)", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 109, pp. 17–28, 2015

- ^ Puljiz, Ivana, "Faience for the empire: A Study of Standardized Production in the Middle Assyrian State", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 100-122, 2021

- ^ Jesper Eidem, Some Remarks on the Iltani Archive from Tell al Rimah, Iraq, vol. 51, pp. 67–78, 1989

- ^ [2] Langlois, Anne-Isabelle. "“You Had None of a Woman’s Compassion”: Princess Iltani from her Archive Uncovered at Tell al-Rimah (18th Century BCE)." Gender and methodology in the ancient Near East: Approaches from Assyriology and beyond 10 (2018): 129

- ^ Sasson, Jack M., "Religion". From the Mari Archives: An Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 235-293, 2015

- ^ Sasson, Jack M., "Culture", From the Mari Archives: An Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 294-342, 2015

Further reading

- Carter, Theresa Howard, "Excavations at Tell al-Rimah, 1964 Preliminary Report", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 178.1, pp. 40-69, 1965

- Stephanie Dalley, "Old Babylonian Trade in Textiles at Tell al Rimah, Iraq", vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 155–159, 1977

- Stephanie Dalley, C.B.F Walker and J.D. Hawkins, "The Old Babylonian Tablets from Al-Rimah", British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1976, ISBN 0-903472-03-1

- Stephanie Dalley, "Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities", Gorgias Press, 2002 ISBN 1-931956-02-2

- Langlois, A. I., "Archibab 2. Les archives de la princesse Iltani découvertes à Tell al-Rimah (XVIIIe siècle av. J.-C.) et l’histoire du royaume de Karana/Qaṭṭara", Mémoires de NABU 18, Paris: SEPOA, 2017

- Barbara Parker, "Middle Assyrian Seal Impressions from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 257–268, 1977

- Carolyn Postgate, David Oates and Joan Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: The Pottery", Aris & Phillips, 1998, ISBN 0-85668-700-6

- J. N. Postgate, "A Neo-Assyrian Tablet from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 31–35, 1970

- J. N. Postgate, "An Inscribed Jar from Tell Al-Rimah", Iraq 40, pp. 71–5, 1978

- Joan Oates, "Late Assyrian Temple Furniture from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 36, no. 1/2, pp. 179–184, 1974

- von Saldern, Axel, "Mosaic Glass from Hasanlu, Marlik, and Tell al-Rimah", Journal of Glass Studies, vol. 8, pp. 9–25, 1966

- C. B. F. Walker, "A Foundation-Inscription from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 27–30, 1970