Códice Casanatense: Difference between revisions

Omnipaedista (talk | contribs) Undid revision 1185211177 by Keyboard Editor (talk) |

m Disambiguating links to Siege of Diu (link changed to Siege of Diu (1538)) using DisamAssist. |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Contents and origin== |

==Contents and origin== |

||

The codex consists of seventy-six [[Watercolor painting|watercolor]] illustrations, one of which is a later addition. Most come with a short description, and include illustrations of people from east Africa, Arabia, Persia, Afghanistan, India, Ceylon, Malaysia, China, and the Moluccas, as well as some insights into fauna, flora, and certain traditions, such as the Hindu religion — previously unknown in Europe. The creator has not been identified and many hypotheses have proven inconclusive.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=23}}<ref name="auto">{{cite journal|url=https://www.academia.edu/7010487|title=Codex Casanatense 1889: an Indo-Portuguese 16th century album in a Roman library|first=Jeremiah|last=Losty|access-date=26 January 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R-3iBQAAQBAJ&dq=Codex+Casanatense+1889&pg=PA355|title=Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History.: Volume 6. Western Europe (1500-1600)|first1=David|last1=Thomas|first2=John A.|last2=Chesworth|date=17 December 2014|publisher=BRILL|isbn=9789004281110|access-date=26 January 2018|via=Google Books}}</ref> Several of its inscriptions provide information as to the date it was made, namely the allusion to the [[siege of Diu]] in 1538, but the absence of any mention of the [[Japanese people|Japanese]], whom the Portuguese contacted in 1541–1543.<ref name="auto"/> It is therefore possible it was made circa 1540.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=28}} |

The codex consists of seventy-six [[Watercolor painting|watercolor]] illustrations, one of which is a later addition. Most come with a short description, and include illustrations of people from east Africa, Arabia, Persia, Afghanistan, India, Ceylon, Malaysia, China, and the Moluccas, as well as some insights into fauna, flora, and certain traditions, such as the Hindu religion — previously unknown in Europe. The creator has not been identified and many hypotheses have proven inconclusive.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=23}}<ref name="auto">{{cite journal|url=https://www.academia.edu/7010487|title=Codex Casanatense 1889: an Indo-Portuguese 16th century album in a Roman library|first=Jeremiah|last=Losty|access-date=26 January 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R-3iBQAAQBAJ&dq=Codex+Casanatense+1889&pg=PA355|title=Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History.: Volume 6. Western Europe (1500-1600)|first1=David|last1=Thomas|first2=John A.|last2=Chesworth|date=17 December 2014|publisher=BRILL|isbn=9789004281110|access-date=26 January 2018|via=Google Books}}</ref> Several of its inscriptions provide information as to the date it was made, namely the allusion to the [[Siege of Diu (1538)|siege of Diu]] in 1538, but the absence of any mention of the [[Japanese people|Japanese]], whom the Portuguese contacted in 1541–1543.<ref name="auto"/> It is therefore possible it was made circa 1540.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=28}} |

||

Its earliest recorded owner was the novice João da Costa of the [[Saint Paul's College, Goa|College of St. Paul of Goa]], who in 1627 sent it to Lisbon, according to information inscribed within the codex. Once in Europe, it was acquired by Cardinal Girolamo Casanata who, on his death in 1700, bequeathed it along with his private collection to the [[Dominican Order]], for the creation of a new library, where it is now kept.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=29}} It was first brought to public attention by the scholar Georg Schurhammer, who published several pictures in the Portuguese historical magazine ''Garcia da Horta'' in the 1950s.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=19}} |

Its earliest recorded owner was the novice João da Costa of the [[Saint Paul's College, Goa|College of St. Paul of Goa]], who in 1627 sent it to Lisbon, according to information inscribed within the codex. Once in Europe, it was acquired by Cardinal Girolamo Casanata who, on his death in 1700, bequeathed it along with his private collection to the [[Dominican Order]], for the creation of a new library, where it is now kept.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=29}} It was first brought to public attention by the scholar Georg Schurhammer, who published several pictures in the Portuguese historical magazine ''Garcia da Horta'' in the 1950s.{{sfn|Matos|1985|p=19}} |

||

Revision as of 18:12, 5 December 2023

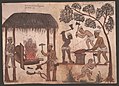

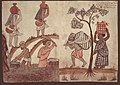

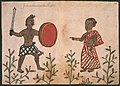

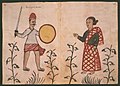

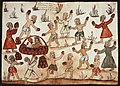

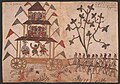

The Códice Casanatense, its popular Portuguese title, or the Codex Casanatense 1889, is a set of 16th-century Portuguese illustrations, which depict peoples and cultures whom the Portuguese frequently had contact with around the Indian and Pacific oceans. It is now kept at the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome, with the official designation of Album di disegni, illustranti usi e costumi dei popoli d'Asia e d'Africa con brevi dichiarazioni in lingua portoghese ("Album of drawings, illustrating the uses and customs of the people of Asia and Africa with brief descriptions in Portuguese language").

Contents and origin

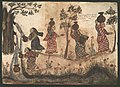

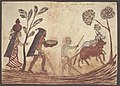

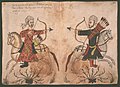

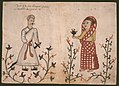

The codex consists of seventy-six watercolor illustrations, one of which is a later addition. Most come with a short description, and include illustrations of people from east Africa, Arabia, Persia, Afghanistan, India, Ceylon, Malaysia, China, and the Moluccas, as well as some insights into fauna, flora, and certain traditions, such as the Hindu religion — previously unknown in Europe. The creator has not been identified and many hypotheses have proven inconclusive.[1][2][3] Several of its inscriptions provide information as to the date it was made, namely the allusion to the siege of Diu in 1538, but the absence of any mention of the Japanese, whom the Portuguese contacted in 1541–1543.[2] It is therefore possible it was made circa 1540.[4]

Its earliest recorded owner was the novice João da Costa of the College of St. Paul of Goa, who in 1627 sent it to Lisbon, according to information inscribed within the codex. Once in Europe, it was acquired by Cardinal Girolamo Casanata who, on his death in 1700, bequeathed it along with his private collection to the Dominican Order, for the creation of a new library, where it is now kept.[5] It was first brought to public attention by the scholar Georg Schurhammer, who published several pictures in the Portuguese historical magazine Garcia da Horta in the 1950s.[6]

The Códice Casanatense provides an extremely rare insight into the culture of the peoples in 16th-century Africa and Asia, and is especially valuable for the study of popular arms and garments of the era.

Gallery

Sub-Saharan Africa

Abyssinia

-

Abyssinian warrior and his wife

Nubia

-

Nubians

Cafreria

-

Inhabitants of the headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa, named Cabo da Boa Esperança and its inhabitants dubbed Cafres by the Portuguese

West Asia

Arabia

-

Bathing scene of the women of Muscat

-

Inhabitants of the Kingdom of Fartakh in the east Arabian coast and Socotra, called Fartaques by the Portuguese

-

Arabian merchants from the Hejaz

-

Farmers from southeastern Arabia, possibly Yemen, called Boduis by the Portuguese

-

"Sailors" from Arabia, probably fishermen

-

Sailors from Arabia, repetition

Mesopotamia

-

"Rumes" (Turks) that inhabit the Red Sea and Basra

-

Marsh Arabs

Hormuz

-

Persian couple from Hormuz

-

A dinner of Portuguese in Hormuz; the climate was hot enough that people purposely flooded their homes

Persia and Afghanistan

-

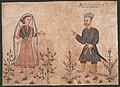

A couple from Shiraz

-

A couple from Khorassan

-

Turkmens from Persia

-

Nautaques, Baloch fishermen who also attacked trade ships

South Asia

Sindh

-

Sindhis

Gujarat

-

"King of Cambay", the Sultan of Gujarat

-

Rajputs, "who inhabit the backwoods of Cambay"

-

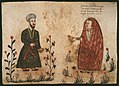

Gujarati couple of a lascarin (foot soldier) and his wife

-

Money changer of Gujarat

-

Merchants of Gujarat

-

Water tank in Gujarat

-

Water sellers of Gujarat

-

Gujarati women

-

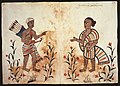

Farmers and land workers of Gujarat

-

Carriage of Gujarat

Northern and Northeastern India

-

Horsemen from Patna

-

Horsewomen from Patna

-

Bengalis

Goa and the Kanara Coast

-

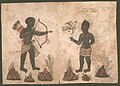

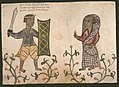

Goan footsoldier, who were known to use longbows

-

Goan blacksmiths

-

Clothes washers, called mainatos by the Portuguese

-

Wheat sellers in Goa

-

Goan farmers

-

A Brahmin goldsmith from Goa

-

Hindu Kanarese, called "gentiles" by the Portuguese

Malabar Coast

-

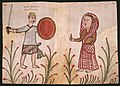

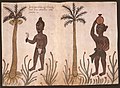

Nayars or Nairs, a Hindu "warrior" caste of the Malabar Coast

-

Descendants of Muslim men married to Indian women, called Naitás ("Navayats") by the Portuguese

-

Malabarese Christians of Saint Thomas

-

Malabarese Muslims (Mappila)

-

Malabarese Jews

Coromandel Coast

-

Badagas, who inhabited the southeastern coast of India

-

People from Orissa, in the eastern coast of India

Ceylon

-

Women of Sri Lanka

-

"Chingalas"; warriors of Sri Lanka, "where the cinnamon is born"

Maldives

-

Maldivians

Southeast Asia

Burma

-

People from the Kingdom of Bago

Malacca

-

Malay "gentiles" of the Kingdom of Malacca

Indonesia

-

Acehnese people

-

Javanese people

-

People from Halmahera, also known as Gilolo

-

Moluccans

-

Bandanese

East Asia

China

-

Chinese

Miscellaneous

Hindu rituals

-

Illustration of the three main deities of Hinduism

-

Hindu marriage, left

-

Hindu marriage, center

-

Hindu marriage, right

-

Hindu ritual of hook swinging

-

Hindu self-sacrifice

-

Hindu self-sacrifice

-

Hindu pilgrims and roving holy men

-

Burial of a living widow

-

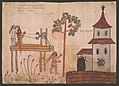

Hindu temple car, crushing a worshiper

The Portuguese in Asia

-

A Portuguese nobleman with his retinue in India

-

"Single Christian women of India" wearing European fashion, and a Portuguese nobleman, presumably proposing marriage

-

Portuguese noblewoman on a palanquin

Fauna and flora

-

Illustration of a Naja snake and a mysterious two headed snake

See also

- Miniature (illuminated manuscript)

- Boxer Codex

- Tipos del País

- Ottoman miniature

- Persian miniature

- Mughal painting

Notes

- ^ Matos 1985, p. 23.

- ^ a b Losty, Jeremiah. "Codex Casanatense 1889: an Indo-Portuguese 16th century album in a Roman library". Retrieved 26 January 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Thomas, David; Chesworth, John A. (17 December 2014). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History.: Volume 6. Western Europe (1500-1600). BRILL. ISBN 9789004281110. Retrieved 26 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Matos 1985, p. 28.

- ^ Matos 1985, p. 29.

- ^ Matos 1985, p. 19.

References

- De Matos, Luis (1985). Imagens do Oriente no século XVI: Reprodução do Códice português da Biblioteca Casanatense. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.