St Mark's Basilica: Difference between revisions

Leptictidium (talk | contribs) Reverting my own edits for now because there seems to be a problem; the source references the 1980 edition, but the ISBN corresponds to the 2002 edition. |

Superior6296 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 247: | Line 247: | ||

Scuola Grande di San Marco Ospedale di Venezia facciata.jpg|alt=photo of facade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco|[[Scuola Grande di San Marco]] |

Scuola Grande di San Marco Ospedale di Venezia facciata.jpg|alt=photo of facade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco|[[Scuola Grande di San Marco]] |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

==Organs== |

|||

===Callido-Trice-Tamburini's Organ=== |

|||

On the choir loft to the left of the presbytery, there is the main organ of the basilica. This, built by Gaetano Callido in 1766, was enlarged by William George Trice in 1893 and by the Tamburini company in 1972 (opus 638). The instrument, with two keyboards of 58 notes each and a pedal board of 30, has mixed transmission: mechanical for the manuals and the pedal, electric for the registers. |

|||

===Callido's Organ=== |

|||

On the choir loft to the right of the presbytery, there is the Gaetano Callido opus 30 pipe organ, built in 1766. In 1909 the instrument was removed (to make room for a new organ, built by the Mascioni company) and in 1995 relocated after a restoration conducted by Franz Zanin. |

|||

The Mascioni organ (opus 284) was pneumatically driven, with two keyboards and pedals. In 1994 it was dismantled, restored and reassembled in the church of Santa Maria della Pace in Mestre. |

|||

The Callido organ has an entirely mechanical transmission, has a single 57-note keyboard with a first octave and a lectern-style pedal, constantly connected to the manual. The case is no longer the original baroque one, but a wooden one with simpler shapes and without decorations. |

|||

===Martino's Organ=== |

|||

It is a small positive organ of the Neapolitan school, from 1720, the work of the organ builder Tommaso de Martino; it was restored by Franz Zanin in 1995 and placed in the apse niche of the epistle. With mechanical transmission, it is equipped with a 45-note manual and has no pedal. |

|||

===Cimmino's Organ=== |

|||

It is a small organ of the Neapolitan school, from 1779, the work of the organ builder Fabrizio Cimmino; it was recovered by Giorgio and Cristian Carrara in 1999 and placed in the Basilica in 2014, next to the altar of the Madonna Nicopeia. With mechanical transmission, it is equipped with a 45-note manual with a short first octave and an 8-note lectern pedalboard, constantly linked to the manual. |

|||

==Mosaics== |

==Mosaics== |

||

Revision as of 22:01, 17 February 2024

| |||||

Main façade of St Mark's Basilica at Piazza San Marco | |||||

| Location | Venice, Italy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Catholic Church | ||||

| Consecrated | 8 October 1094 | ||||

| Titular saint | Mark the Evangelist | ||||

| History | |||||

| |||||

| Designation | Cathedral (minor basilica) 1807–present | ||||

| Episcopal see | Patriarchate of Venice | ||||

| |||||

| Designation | Ducal chapel c. 836–1797 | ||||

| Tutelage | Doge of Venice | ||||

| Building details | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Built | c. 829–c. 836 | ||||

| Rebuilt | c. 1063–1094 | ||||

| Styles | Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic | ||||

| |||||

| Length | 76.5 metres (251 ft) | ||||

| Width | 62.6 metres (205 ft) | ||||

| Outer height (central dome) | 43 metres (141 ft) | ||||

| Inner height (central dome) | 28.15 metres (92.4 ft)[1] | ||||

| Map | |||||

| |||||

The Patriarchal Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark (Template:Lang-it), commonly known as St Mark's Basilica (Template:Lang-it; Template:Lang-vec), is the cathedral church of the Patriarchate of Venice; it became the episcopal seat of the Patriarch of Venice in 1807, replacing the earlier cathedral of San Pietro di Castello. It is dedicated to and holds the relics of Saint Mark the Evangelist, the patron saint of the city.

The church is located on the eastern end of Saint Mark's Square, the former political and religious centre of the Republic of Venice, and is attached to the Doge's Palace. Prior to the fall of the republic in 1797, it was the chapel of the Doge and was subject to his jurisdiction, with the concurrence of the procurators of Saint Mark de supra for administrative and financial affairs.

The present structure is the third church, begun probably in 1063 to express Venice's growing civic consciousness and pride. Like the two earlier churches, its model was the sixth-century Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, although accommodations were made to adapt the design to the limitations of the physical site and to meet the specific needs of Venetian state ceremonies. Middle-Byzantine, Romanesque, and Islamic influences are also evident, and Gothic elements were later incorporated. To convey the republic's wealth and power, the original brick façades and interior walls were embellished over time with precious stones and rare marbles, primarily in the thirteenth century. Many of the columns, reliefs, and sculptures were spoils stripped from the churches, palaces, and public monuments of Constantinople as a result of the Venetian participation in the Fourth Crusade. Among the plundered artefacts brought back to Venice were the four ancient bronze horses that were placed prominently over the entry.

The interior of the domes, the vaults, and the upper walls were slowly covered with gold-ground mosaics depicting saints, prophets, and biblical scenes. Many of these mosaics were later retouched or remade as artistic tastes changed and damaged mosaics had to be replaced, such that the mosaics represent eight hundred years of artistic styles. Some of them derive from traditional Byzantine representations and are masterworks of Medieval art; others are based on preparatory drawings made by prominent Renaissance artists from Venice and Florence, including Paolo Veronese, Tintoretto, Titian, Paolo Uccello, and Andrea del Castagno.

History

Participazio church (c. 829–976)

Several medieval chronicles narrate the translatio, the removal of Saint Mark's body from Alexandria in Egypt by two Venetian merchants and its transfer to Venice in 828/829.[2] The Chronicon Venetum further recounts that the relics of Saint Mark were initially placed in a corner tower of the castrum, the fortified residence of the Doge and seat of government located on the site of the present Doge's Palace.[3] Doge Giustiniano Participazio (in office 827–829) subsequently stipulated in his will that his widow and his younger brother and successor Giovanni (in office 829–832) were to erect a church dedicated to Saint Mark wherein the relics would ultimately be housed. Giustiniano further specified that the new church was to be built between the castrum and the Church of Saint Theodore to the north. Construction of the new church may have actually been underway during Giustinian's lifetime and was completed by 836 when the relics of Saint Mark were transferred.[4]

Although the Participazio church was long believed to have been a rectangular structure with a single apse, soundings and excavations have demonstrated that St Mark's was from the beginning a cruciform church with at least a central dome, likely in wood.[5][6] It has not been unequivocally established if each of the four crossarms of the church had a similar dome or were instead covered with gabled wooden roofs.[7]

The prototype was the Church of the Holy Apostles (demolished 1461) in Constantinople.[8] This radical break with the local architectural tradition of a rectangular plan in favour of a centrally planned Byzantine model reflected the growing commercial presence of Venetian merchants in the imperial capital as well as Venice's political ties with Byzantium. More importantly, it underscored that St Mark's was intended not as an ecclesiastical seat but as a state sanctuary.[9]

Remnants of the Participazio church likely survive and are generally believed to include the foundations and lower parts of several of the principal walls, including the western wall between the nave and the narthex. The great entry portal may also date to the early church as well as the western portion of the crypt, under the central dome, which seems to have served as the base for a raised dais upon which the original altar was located.[6][10][note 1]

Orseolo church (976–c. 1063)

The Participazio church was severely damaged in 976 during the popular uprising against Doge Pietro IV Candiano (in office 959–976) when the fire that angry crowds had set to drive the Doge from the castrum spread to the adjoining church. Although the structure was not completely destroyed, it was compromised to the point that the Concio, the general assembly, had to alternatively convene in the cathedral of San Pietro di Castello to elect Candiano's successor, Pietro I Orseolo (in office 976–978).[11] Within two years, the church was repaired and at the sole expense of the Orseolo family, indications that the actual damage was relatively limited. Most likely, the wooden components had been consumed, but the walls and supports remained largely intact.[12]

Nothing certain is known of the appearance of the Orseolo church. But given the short duration of the reconstruction, it is probable that work was limited to repairing damage with little innovation.[8][13] It was at this time, however, that the tomb of Saint Mark, located in the main apse, was surmounted with brick vaults, creating the semi-enclosed shrine that would later be incorporated into the crypt when the floor of the chancel was raised during the construction of the third church.[14]

Contarini church (c. 1063–present)

Construction

Civic pride led many Italian cities in the mid-eleventh century to begin erecting or rebuilding their cathedrals on a grand scale.[15] Venice was similarly interested in demonstrating its growing commercial wealth and power, and probably in 1063, under Doge Domenico I Contarini (in office 1043–1071), St Mark's was substantially rebuilt and enlarged to the extent that the resulting structure appeared entirely new.[16]

The northern transept was lengthened, likely by incorporating the southern lateral nave of the Church of Saint Theodore.[17] Similarly, the southern transept was extended, perhaps by integrating a corner tower of the castrum. Most significantly, the wooden domes were rebuilt in brick. This required strengthening the walls and piers in order to support the new heavy barrel vaults, which in turn were reinforced by arcades along the sides of the northern, southern, and western crossarms. The vaults of the eastern crossarm were supported by inserting single arches that also served to divide the chancel from the choir chapels in the lateral apses.[18][19]

In front of the western façade, a narthex was built. To accommodate the height of the existing great entry, the vaulting system of the new narthex had to be interrupted in correspondence to the portal, thus creating the shaft above that was later opened to the interior of the church. The crypt was also enlarged to the east, and the high altar was moved from under the central dome to the chancel, which was raised, supported by a network of columns and vaults in the underlying crypt.[20] By 1071, work had progressed far enough that the investiture of Doge Domenico Selvo (in office 1071–1084) could take place in the unfinished church.[16]

Work on the interior began under Selvo who collected fine marbles and stones for the embellishment of the church and personally financed the mosaic decoration, hiring a master mosaicist from Constantinople.[21][22] The Pala d'Oro (golden altarpiece), ordered from Constantinople in 1102, was installed on the high altar in 1105.[23][24] For the consecration under Doge Vitale Falier Dodoni (in office 1084–1095), various dates are recorded, most likely reflecting a series of consecrations of different sections.[25] The consecration on 8 October 1094 is considered to be the dedication of the church.[26] On that day, the relics of Saint Mark were also placed into the new crypt.[27]

Embellishment

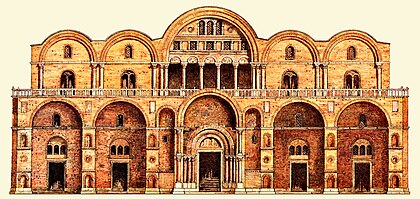

As built, the Contarini church was a severe brick structure. Adornment inside was limited to the columns of the arcades, the balusters and parapets of the galleries, and the lattice altar screens. The wall surfaces were decorated with moulded arches that alternated with engaged brickwork columns as well as niches and a few cornices.[28] With the exception of the outside of the apse and the western façade that faced Saint Mark's Square, the stark brick exterior was enlivened only by receding concentric arches in contrasting brick around the windows.[29]

The western façade, comparable to middle-Byzantine churches erected in the tenth and eleventh centuries, was characterized by a series of arches set between protruding pillars.[30] The walls were pierced by windows set in larger blind arches, while the intervening pillars were adorned with niches and circular patere made of rare marbles and stones that were surrounded with ornamental frames.[31] Other decorative details, including friezes and corbel tables, reflected Romanesque trends, an indication of the taste and craftsmanship of the Italian workers.[32]

With few exceptions, most notably the juncture of the southern and western crossarms, both the exterior and interior of the church were subsequently sheathed with revetments of marble and precious stones and enriched with columns, reliefs, and sculptures.[33] Many of these ornamental elements were spolia taken from ancient or Byzantine buildings.[34] Particularly in the period of the Latin Empire (1204–1261), following the Fourth Crusade, the Venetians pillaged the churches, palaces, and public monuments of Constantinople and stripped them of polychrome columns and stones. Once in Venice, some of the columns were sliced for revetmets and patere; others were paired and spread across the façades or used as altars.[35] Despoliation continued in later centuries, notably during the Venetian–Genoese Wars.[36][37] Venetian sculptors also integrated the spoils with local productions, copying the Byzantine capitals and friezes so effectively that some of their work can only be distinguished with difficulty from the originals.[38]

Later modifications

In addition to the sixteen windows in each of the five domes, the church was originally lit by three or seven windows in the apse and probably eight in each of the lunettes.[39] But many of these windows were later walled up to create more surface space for the mosaic decoration, with the result that the interior received insufficient sunlight, particularly the areas under the galleries which remained in relative darkness. The galleries were consequently reduced to narrow walkways with the exception of the ends of the northern, southern, and western crossarms where they remain. These walkways maintain the original relief panels of the galleries on the side facing the central section of the church. On the opposite side, new balustrades were erected.[40]

The narthex of the Contarini church was originally limited to the western side. As with other Byzantine churches, it extended laterally beyond the façade on both sides and terminated in niches, of which the northern remains. The southern terminus was separated by a wall in the early twelfth century, thus creating an entry hall that opened on the southern façade toward the Doge's Palace and the waterfront.[41] In the early thirteenth century, the narthex was extended along the northern and southern sides to completely surround the western crossarm.[42]

Also, in the first half of the thirteenth century, the original low-lying brick domes, typical of Byzantine churches, were surmounted with higher, outer shells supporting bulbous lanterns with crosses.[43] These wooden frames covered in lead provided more protection from weathering to the actual domes below and gave greater visual prominence to the church.[44][45][46] Various Near-Eastern models have been suggested as sources of inspiration and construction techniques for the heightened domes, including the Al-Aqsa and Qubbat aṣ-Ṣakhra mosques in Jerusalem and the conical frame erected over the dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the early thirteenth century.[47]

Architecture

Exterior

The three exposed façades result from a long and complex evolution. Particularly in the thirteenth century, the exterior appearance of the church was radically altered: the patterned marble encrustation was added, and a multitude of columns and sculptural elements was applied to enrich the state church. It is probable that structural elements were also added to the façades or modified.[48]

Western façade

The exterior of the basilica is divided into two registers. On the western façade, the lower register is dominated by five deeply recessed portals that alternate with large piers.[30] The lower register was later completely covered with two tiers of precious columns, largely spoils from the Fourth Crusade.[33]

Consistent with Byzantine traditions, the sculptural elements are largely decorative: only in the arches that frame the doorways is there a functional use of sculpture that articulates the architectural lines.[49] In addition to the reliefs in the spandrels, the sculpture at the lower level, relatively limited, includes narrow Romanesque bands, statues, and richly carved borders of foliage mixed with figures derived from Byzantine and Islamic traditions. The eastern influence is most pronounced in the tympana over the northern-most and southern-most portals.[50]

The iconographic programme is expressed primarily in the mosaics in the lunettes. In the lower register, those of the lateral portals narrate the translatio, the translation of Saint Mark's relics from Alexandria to Venice. From right to left, they show the removal of the saint's body from Egypt, its arrival in Venice, its veneration by the Doge, and its deposition in the church.[51] This last mosaic is the only one on the façade that survives from the thirteenth century; the others were remade in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.[52][53] The general appearance of the lost compositions is recorded in Gentile Bellini's Procession in Piazza San Marco (1496), which also documents the earlier gilding on the façade.[51]

The upper register is enriched with an elaborate Gothic crowning, executed in the late-fourteenth/early-fifteenth centuries. The original lunettes, transformed into ogee arches, are outlined with foliage and topped with statues of four military saints over the lateral lunettes and of Saint Mark flanked by angels over the central lunette, the point of which contains the winged lion of Saint Mark holding a book with the angelic salutation of the praedestinatio: "Peace to you Mark, my Evangelist" ("Pax tibi Marce evangelista meus").[note 2] The intervening aediculae with pinnacles house figures of the Four Evangelists and on the extremities, facing one another, the Virgin and the Archangel Gabriel in allusion to Venice's legendary foundation on the 25 March 421, the feast of the Annunciation.[55]

Culminating in the Last Judgment over the main portal, the sequence of mosaics in the lateral lunettes of the upper register present scenes of Christ's victory over death: from left to right, the Descent from the Cross, the Harrowing of Hell, the Resurrection, and the Ascension.[51] The central lunette was originally blind and may have been pierced by several smaller windows; the present large window was inserted after the fire of 1419 destroyed the earlier structure.[56] The reliefs of Christ and the Four Evangelists, now inserted into the northern façade, may also survive from the original decoration of the central lunette.[57]

The four gilded bronze horses were among the early spoils brought from Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade.[58] They were part of a quadriga adorning the Hippodrome and are the only equestrian team to survive from classical Antiquity.[59] In the mid-thirteenth century, they were installed prominently on the main façade of St Mark's as symbols of Venice's military triumph over Byzantium and of its newfound imperial status as the successor of the Byzantine Empire.[60] Since 1974 the original four horses are preserved inside, having been substituted with copies on the balcony over the central portal.[61]

Northern façade

The aediculae on the northern façade contain statues of the four original Latin Doctors of the Church: Jerome, Augustine, Ambrose, and Gregory the Great. Allegorical figures of Prudence, Temperance, Faith, and Charity top the lunettes.[62]

Southern façade

The Gothic crowning continues in the upper register of the southern façade, the lunettes being topped with the allegorical figures of Justice and Fortitude and the aediculae housing statues of Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Paul the Hermit.[63]

The southern façade is the most richly encrusted façade with rare marbles, spoils, and trophies, including the so-called pillars of Acre, the statue of the four tetrarchs embedded into the external wall of the treasury, and the porphyry imperial head on the south-west corner of the balcony, traditionally believed to represent Justinian II and popularly identified as Francesco Bussone da Carmagnola.[64][65]

After a section of the narthex was partitioned off between 1100 and 1150 to create an entry hall, the niche that had previously marked the southern end of the narthex was removed, and the corresponding arch on the southern façade was opened to establish a second entry.[66] Like the entry on the western façade, the passage was distinguished with precious porphyry columns.[67] On either side, couchant lions and griffins were placed. Presumably, the southern entry was also flanked by the two carved pillars long believed to have been brought to Venice from the Genoese quarter in St Jean d'Acre as booty of the first Venetian–Genoese war (1256–1270) but actually spoils of the Fourth Crusade, taken from the Church of St Polyeuctus in Constantinople.

Between 1503 and 1515, the entry hall was transformed into the funerary chapel of Giovanni Battista Cardinal Zen, bishop of Vicenza, who had bequeathed a large portion of his wealth to the Venetian Republic, asking to be entombed in St Mark's.[68] The southern entrance was consequently closed, blocked by the altar and a window above, and although the griffins remain, much of the decoration was transferred or destroyed.[69] The pillars were moved slightly eastward.[70]

Entry hall (Zen Chapel)

The decoration of the southern entry hall to the church was redone in the thirteenth century in conjunction with work in the adjoining narthex; of the original appearance of the entry hall, nothing is known. The present mosaic cycle in the barrel vault forms the prelude to the mosaic cycle on the main façade, which narrates the translation of Saint Mark's relics from Alexandria in Egypt to Venice. The events depicted include the praedestinatio, the angelic prophecy that Mark would one day be buried in Venice, which affirms Venice's divine right to possess the relics. The authority of Saint Mark is demonstrated in the scenes that show the writing of his Gospel which is then presented to Saint Peter. Particular relevance is also given to the departure of Saint Mark for Egypt and his miracles there, which creates continuity with the opening scene on the façade, depicting the removal of the body from Alexandria.[71]

Although largely redone in the nineteenth century, the apse above the doorway that leads into the narthex probably maintains the overall aspect of the decoration from the first half of the twelfth century with the Virgin flanked by angels, a theme common in middle-Byzantine churches.[72]

Interior

Although St Mark's was modelled after the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, ceremonial needs and limitations posed by the pre-existing walls and foundations made it necessary to adapt the design.[73] The cruciform plan with five domes was maintained. However the Holy Apostles was a true centrally planned church: the central dome, larger than the others, was alone pierced with windows, and the altar was located underneath. There was no distinction between the four crossarms: no apse existed and double-tiered arcades surrounded the interior on all sides. In contrast, the longitudinal axis was emphasized to create a space appropriate for processions associated with state ceremonies. Both the central and western domes are larger, accentuating the progression along the nave, and by means of a series of increasingly smaller arches, the nave visually narrows towards the raised chancel in the eastern crossarm, where the altar stands.[32] The crossarms of the transept are shorter and narrower. Optically, their height and width are further reduced by the insertion of arches, supported on double columns within the barrel vaults. The domes of the transept and the chancel are also smaller.[74]

As with the Holy Apostles, each dome rests on four barrel vaults, those of the central dome rising from quadripartite (four-legged) piers. But the two-tiered arcades that reinforced the vaults in the Holy Apostles were modified. In St Mark's there are no upper arcades, and as a result the aisles are less isolated from the central part of the church. The effect is of more unified sense of space and an openness that have parallels in other Byzantine churches constructed in the eleventh century, an indication that the chief architect was influenced by middle-Byzantine architectural models in addition to the sixth-century Church of the Holy Apostles.[30][75]

Chancel and choir chapels

The chancel is enclosed by a Gothic altar screen, dated 1394. It is surmounted by a bronze and silver Crucifix, flanked by statues of the Virgin and Saint Mark, together with the Twelve Apostles.[76] On the left of the screen is the ambo for readings from Scripture, while the on the right is the platform from which the newly elected Doge was presented to the people.[77]

Behind, marble banisters mark the limit of the choir, which after the reorganization by Doge Andrea Gritti (in office 1523–1538) was utilized by the Doge, civic leaders, and foreign ambassadors.[78][79] Prior to the sixteenth century, the Doge's throne was located near the choir chapel of Saint Clement I, whose doorway opened to the courtyard of the Doge's Palace. The chapel was reserved for the Doge's private use.[80] From the window above, which communicates with his private apartments, it was also possible for the Doge to assist at mass in the church.

The tribunes on either side of the chancel are faced with bronze reliefs that portray events in the life of Saint Mark and his miracles.[81] Beyond the banisters is the presbytery, reserved for the clergy, with the high altar which since 1835 contains the relics of Saint Mark, previously located in the crypt.[81] The ciborium above the altar is supported by four intricately carved columns with scenes that narrate the lives of Christ and the Virgin. The age and provenance of the columns is disputed, with proposals ranging from sixth-century Byzantium to thirteenth-century Venice.[82] The altarpiece, originally designed as an antependium, is the Pala d'Oro, a masterpiece of Byzantine enamels on gilded silver.[83][84]

The two choir chapels, located on either side of the chancel, occupy the space corresponding to the lateral aisles in the other crossarms. They are connected to the chancel through archways which also serve to reinforce the barrel vaults supporting the dome above.[85] The choir chapel on the northern side is dedicated to Saint Peter. Historically, it was the principal area for the clergy.[86][87] The mosaic decoration in the vaults above the chapels largely narrates the life of Saint Mark, including the events of the translatio. They constitute the oldest surviving representation of the transfer of Saint Mark's relics to Venice.[88]

Side altars and chapels

The side altars in the transept were used primarily by the faithful. In the northern crossarm, the altar was originally dedicated to Saint John the Evangelist: the mosaics in the dome above show the aged figure of Saint John, surrounded by five scenes of his life in Ephesus.[89] The stone relief of Saint John, placed on the eastern wall of the crossarm in the thirteenth century, was later moved to the northern façade of the church, probably when the altar was rededicated in 1617 to the Madonna Nicopeia, a venerated Byzantine icon from the late-eleventh/early-twelfth century.[64][90]

The date and the circumstances of the icon's arrival in Venice are not documented.[91] Most likely one of many sacred images taken from Constantinople at the time of the Latin Empire, it was deposited in St Mark's treasury, with no specific importance associated.[92] It began to acquire significance for the Venetians in the fourteenth century when it was framed with Byzantine enamels looted from the Pantokrator in Contantinople. At that time, it may have been first carried in public procession to invoke the Virgin's intercession in ridding the city of the Black Death.[93] The icon acquired a political role as the palladium of Venice in the sixteenth century when it came to be identified as the sacred image that had been carried into battle by various Byzantine emperors.[92][94] In 1589, the icon was transferred to the small Chapel of Saint Isidore where it was made accessible to the public, and subsequently it was placed on the side altar in the northern crossarm.[95] It was first referred to as the Madonna Nicopeia (Nikopoios, Bringer of Victory) in 1645.[92]

The altar in the southern crossarm was initially dedicated to Saint Leonard, the sixth-century Frankish saint who became widely popular at the time of the Crusades as his intercession was sought to liberate prisoners from the Muslims. He is shown in the dome above, together with other saints particularly venerated in Venice: Blaise, Nicholas, and Clement I.[96] The altar was rededicated in 1617 to the True Cross, and since 1810, it has been the Altar of the Blessed Sacrament.[97]

The long-neglected relics of Saint Isidore of Chios, brought to Venice in 1125 by Doge Domenico Michiel (in office 1117–1130) on return from his military expedition in the Aegean, were rediscovered in the mid-fourteenth century, and upon the initiative of Doge Andrea Dandolo (in office 1343–1354), the Chapel of Saint Isidore was constructed between 1348 and 1355 to house them.[98] An annual feast (16 April) was also established in the Venetian liturgical calendar.[99]

The Mascoli Chapel, utilized by the homonymous confraternity after 1618, was decorated under Doge Francesco Foscari (in office 1423–1457) and dedicated in 1430.[100][101]

Against the piers that support the central dome, on either side of the chancel, Doge Cristoforo Moro (in office 1462–1471) erected at his personal expense two altars dedicated to Saint Paul and Saint James. The pier behind the Altar of Saint James is where the relics of Saint Mark are said to have been rediscovered in 1094: the miraculous event is depicted in the mosaics on the opposite side of the crossarm.[102]

Baptistery

The date of construction of the baptistery is not known, but it is likely to have been under Doge Giovanni Soranzo (in office 1312–1328), whose tomb is located in the baptistery, an indication that he was responsible for the architectural adaptation. Similarly entombed in the baptistery is Doge Andrea Dandolo who carried out the decorative programme at his personal expense.[103] The mosaics present scenes from the life of Saint John the Baptist on the walls and, in the ante-baptistery, the infancy of Christ.[104] Directly above the bronze font, designed by Sansovino, the dome contains the dispersion of the Apostles, each shown in the act of baptizing a different nationality in reference to Christ's command to preach the Gospel to all people.[105] The second dome, above the altar, presents Christ in glory surrounded by the nine angelic choirs. The altar is a large granite rock, which according to tradition was brought to Venice from Tyre following the Venetian conquest. It is said to be the rock upon which Christ stood to preach to the people of Tyre.[106]

Sacristy

In 1486, Giorgio Spavento, as proto (consultant architect and buildings manager), designed a new sacristy, connected to both the presbytery and the choir chapel of Saint Peter; the location of the earlier sacristy is not known. It was Spavento's first project and the only one he oversaw to completion. Decoration began in 1493. The cabinets, used for storing reliquaries, monstrances, vestments, and liturgical objects and books, were inlaid by Antonio della Mola and his brother Paolo and show scenes from the life of Saint Mark. The mosaic decoration of the vault, depicting Old-Testament prophets, was designed by Titian and executed between 1524 and 1530.[107][108]

Behind the sacristy is the church, also by Spavento, dedicated to Saint Theodore, the first patron saint of Venice. Constructed between 1486 and 1493 in an austere Renaissance style, it served as the private chapel for the canons of the basilica and, later, as the seat of the Venetian Inquisition.[109]

Influence

As the state church, St Mark's was a point of reference for Venetian architects. Its influence during the Gothic period seems to have been limited to decorative patterns and details, such as the portal and painted wall decoration in the Church of Santo Stefano and the portal of the Church of the Madonna dell'Orto, consisting of an ogee arch with flame-like relief sculpture reminiscent of the crockets on St Mark's.[110]

In the early Renaissance, despite the introduction of classical elements into Venetian architecture by Lombard stonecutters, faithfulness to local building traditions remained strong.[111] In the façades of Ca' Dario and the Church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli, surface decoration in emulation of St Mark's is the principal characteristic, and the overall effect derives from the rich encrustation of shimmering coloured marbles and the circular patterns, derived from the basilica.[112] Similarly, the Foscari Arch in the courtyard of the Doge's Palace is based on ancient triumphal arches but owes its detailing to the basilica: the superimposed columns clustered together, the Gothic pinnacles, and the crowning statuary.[113][114] At the Scuola Grande di San Marco, the reference to St Mark's is made in the series of lunettes along the roofline which recalls the profile of the basilica.[115]

-

Santo Stefano

-

Foscari Arch

Organs

Callido-Trice-Tamburini's Organ

On the choir loft to the left of the presbytery, there is the main organ of the basilica. This, built by Gaetano Callido in 1766, was enlarged by William George Trice in 1893 and by the Tamburini company in 1972 (opus 638). The instrument, with two keyboards of 58 notes each and a pedal board of 30, has mixed transmission: mechanical for the manuals and the pedal, electric for the registers.

Callido's Organ

On the choir loft to the right of the presbytery, there is the Gaetano Callido opus 30 pipe organ, built in 1766. In 1909 the instrument was removed (to make room for a new organ, built by the Mascioni company) and in 1995 relocated after a restoration conducted by Franz Zanin.

The Mascioni organ (opus 284) was pneumatically driven, with two keyboards and pedals. In 1994 it was dismantled, restored and reassembled in the church of Santa Maria della Pace in Mestre.

The Callido organ has an entirely mechanical transmission, has a single 57-note keyboard with a first octave and a lectern-style pedal, constantly connected to the manual. The case is no longer the original baroque one, but a wooden one with simpler shapes and without decorations.

Martino's Organ

It is a small positive organ of the Neapolitan school, from 1720, the work of the organ builder Tommaso de Martino; it was restored by Franz Zanin in 1995 and placed in the apse niche of the epistle. With mechanical transmission, it is equipped with a 45-note manual and has no pedal.

Cimmino's Organ

It is a small organ of the Neapolitan school, from 1779, the work of the organ builder Fabrizio Cimmino; it was recovered by Giorgio and Cristian Carrara in 1999 and placed in the Basilica in 2014, next to the altar of the Madonna Nicopeia. With mechanical transmission, it is equipped with a 45-note manual with a short first octave and an 8-note lectern pedalboard, constantly linked to the manual.

Mosaics

Decorative programme

Interior

The location of the main altar within the apse necessarily affected the decorative programme.[116] The Christ Pantocrator, customarily located in the central dome over the altar, was placed in the semi-dome of the apse.[117] Below, interspersed with three windows, are late-eleventh and early-twelfth-century mosaics that portray Saint Nicholas of Myra, Saint Peter, Saint Mark, and Saint Hermagoras of Aquileia as the protectors and patrons of the state, Saint Nicholas being specifically the protector of seafarers.[118]

Over the high altar in the eastern crossarm is the Dome of Immanuel (God with us). It presents a young Christ in the centre, surrounded by stars. Radially arranged underneath are standing figures of the Virgin and Old-Testament prophets, the latter bearing scrolls with passages that largely refer to the Incarnation.[119] Rather than seraphim as was customary in middle-Byzantine churches, the pendentives of the dome show the symbols of the Four Evangelists.[120]

An extensive cycle narrating the Life of Christ covers much of the interior, with the principal events located along the longitudinal axis. The eastern vault, between the central dome and the chancel, contains the major events of the infancy (Annunciation, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation in the Temple) along with the Baptism of Christ and the Transfiguration. The western vault depicts the events of the Passion of Jesus on one side (the kiss of Judas, the trial before Pilate, and the Crucifixion) and the Resurrection on the other side (the Harrowing of Hell and the post-resurrection appearances). A secondary series illustrating Christ's miracles is located in the transepts.[121] The series seems to have derived from an eleventh-century Byzantine Gospel.[122] The transepts also contain a detailed cycle of the Life of the Virgin: these scenes were probably derived from an eleventh-century illuminated manuscript of the Protogospel of James from Constantinople.[123][124] As a prelude, a Tree of Jesse showing the ancestors of Christ was added to the end wall of the northern crossarm between 1542 and 1551.[125] Throughout the various narrative cycles, Old-Testament prophets are portrayed holding texts that relate to the New-Testament scenes nearby.[126]

The Dome of the Ascension occupies the central position, whereas in the Church of the Holy Apostles it was located over the southern crossarm.[127] The dome, executed in the late twelfth century, is exemplary of middle-Byzantine prototypes in Constantinople.[128] In the centre Christ ascends, accompanied by four angels and surrounded by standing figures of the Virgin, two angels, and the Twelve Apostles. As customary for the central dome in middle-Byzantine churches, the pendentives contain the Four Evangelists, each with his gospel.[120]

As in the Church of the Holy Apostles, the Dome of Pentecost is located over the western crossarm.[129] In the centre is an hetoimasia, an empty throne with a book and dove. Radiating outward are silver rays which fall on the heads of the Apostles seated around the outer rim of the dome, each with a flame on his head. In keeping with Pentecost, as the institution of the Church, the side vaults and walls of the western crossarm largely illustrate the subsequent missionary activities of the Apostles and their deaths as martyrs.[127] The specific events in the lives of the various Apostles and the manner of their deaths adhere to Western traditions, as narrated in Latin martyrologies that derive in part from the Book of Acts but to a greater extent from apocryphal sources. However, the single representations and the overall concept of presenting the lives of the saints in a composition that combines several events together in one scene have their parallels in Greek manuscript illustrations of the middle-Byzantine period.[130]

The western vault illustrates Saint John's vision of the Apocalypse and the Last Judgement. On the wall below there is a thirteenth-century deesis with Christ enthroned between the Virgin and Saint Mark.[131]

Narthex

The decorative programme of the western and northern wings of the narthex seems to have been planned in its entirety in the thirteenth century when the eleventh-century narthex was extended along the northern and southern sides of the western crossarm. However, a stylistic change in the mosaics is evident in the northern wing, indicating that the execution of the programme was interrupted, presumably to await the completion of the vaulting system.[42]

Unlike in middle-Byzantine churches where the theme of the Last Judgement is often represented in the narthex, the decorative programme narrates the stories of Genesis and Exodus: the main subjects are the Creation and the Tower of Babel along with the lives of Noah, Abraham, Joseph, and Moses.[132] Special emphasis is given to the stories of the sacrifice of Abel and the hospitality of Abraham, located prominently in the lunettes on either side of the entry to the church, due to the analogies with Christ's death and the Eucharistic meal.[133]

It has long been recognized that the individual scenes are very close to those of the Cotton Genesis, an important fourth or fifth-century Greek illuminated manuscript copy of the Book of Genesis: about a hundred of the 359 miniatures in the manuscript were used. Of Egyptian origin, the manuscript may have reached Venice as a result of the commercial relations of the Venetians in the Eastern Mediterranean or as booty of the Fourth Crusade.[134] The sixth-century Vienna Genesis was also in Venice in the early thirteenth century and may have influenced artistic choices.[135] With regard to the Dome of Moses, the scenes most closely resemble Palaeologan art, suggesting an unknown manuscript from the third quarter of the thirteenth century as the iconographic source.[136]

While the Byzantine renderings of the Old-Testament stories in illuminated manuscripts provided suitable models, Byzantine churches themselves did not generally give importance to the Old Testament in their decoration, considering the stories to be shadows of the history of salvation, inferior to the reality of the New Testament. The impetus for the Venetians to choose the Old Testament as the theme of the narthex was instead of western derivation and reflected an interest that had developed in Rome beginning in the late eleventh century.[137]

The narration begins in correspondence to the former southern entry of the church with the Dome of the Creation, which opens with the spirit of God hovering above the waters and concludes with Adam and Eve cast out from the Garden of Eden. As in the Cotton Genesis, Christ is portrayed as the agent of creation.[138] Underneath, the pendentives contain cherubim, the guardians of Eden, and the lunettes illustrate the story of Cain and Abel.[139] The stories of Noah and of the Tower of Babel with the confusion of tongues and the dispertion of the nations occupy the vaults on either side of the entry to the church.[140] The story of Abraham, from the calling of the patriarch to the circumcision of Isaac, is narrated in a single dome and the two lunettes underneath, whereas the story of Joseph, the most extensive, occupies the next three domes.[141] The story of Moses, until the Crossing of the Red Sea, is limited to the final bay.[142]

Style

The oldest mosaics in St Mark's, located in the niches of the entry porch in the narthex, may date to as early as 1070.[144] Although Byzantine in style, they are somewhat antiquated with respect to contemporary trends in Byzantium. Most likely, they were executed by mosaicists who had left Constantinople in the mid-eleventh century to work on the cathedral of Torcello and then remained in the local area.[145] More modern but still archaic in style are the figures in the main apse which were done in the late-eleventh and early-twelfth centuries.[146]

The most important period of decoration was the twelfth century when Venice's relations with Byzantium alternated between political tensions that limited artistic influence from the East and moments of intense trade and cooperation that favoured the Venetians' awareness of eastern prototypes as well as the influx of Byzantine mosaicists and materials.[147] The three figures in the Dome of Immanuel that date to the first quarter of the century (Jeremiah, Hosea, and Habakkuk) are the work of highly skilled mosaicists, likely Greek-trained. They demonstrate the greater classicism and realism of middle-Byzantine painting in Constantinople but also local trends in the harsher and broken lines.[148] In succeeding phases of work in the choir chapels and the transept, Byzantine miniatures were copied more or less faithfully for the mosaics, but any eastern influence that could reflect the latest artistic developments in Constantinople is hardly traceable.[149] A new and direct awareness of artistic developments in Constantinople is indicated in the Dome of Pentecost, executed sometime in the first half of the twelfth century.[150]

In the last third of the twelfth century, a large portion of the mosaics in the Dome of Immanuel and the entirety of the Dome of the Ascension and of several vaults in the western crossarm had to be completely redone in consequence of a catastrophic event, the nature and date of which are not known.[153] Local influence is evident. But the more vigorous poses, agitated draperies, expressiveness, and heightened contrast show the partial assimilation of the developing dynamic style in Constantinople.[154] The mosaics in the Dome of the Ascension and those depicting the Passion in the nearby vault represent the maturity of the Venetian mosaic school and are one of the great achievements of Medieval art.[155]

After the removal of the galleries, the mosaic decoration was extended onto the lower walls, beginning in the thirteenth century. The first mosaic, depicting the Agony in the Garden, represents a synthesizing of various traditions, both eastern and western. Traces remain of the complicated patterns of the late Komnenian period. But the statuesque quality of the figures, which are also more rounded, reflect contemporary developments in Byzantine art such as can be seen at Studenica Monastery. Concurrently, an elegance associated with western Gothic appears and is fused with the Byzantine traditions. The Gothic influence becomes more pronounced in later mosaics of the period with patterned backgrounds that derive from the stained-glass windows in French churches.[156]

The interior mosaics were apparently complete by the 1270s, with work on the narthex continuing into the 1290s. Although some activity must have still been underway in 1308 when the Great Council allowed a glass furnace on Murano to produce mosaic material for St Mark's during the summer, by 1419 no competent mosaicist remained to repair the extensive damage to the main apse and western dome caused by a fire that year. The Venetian government had to consequently seek assistance from the Signoria of Florence which sent Paolo Uccello.[157] Other Florentine artists, including Andrea del Castagno, were also active in St Mark's in the mid-fifteenth century, introducing a sense of perspective largely achieved with architectural settings. In this same period, Michele Giambono executed mosaics.[158]

By the time a new fire in 1439 made repairs once again necessary, a number of Venetian mosaicists had been trained. Some of the replacement mosaics they created show a Florentine influence; others reflect Renaissance developments in the detailing and the modelling of the figures. But overall the replacement mosaics in this period closely imitated the design of the damaged works and were intended to look medieval.[159]

Efforts to maintain the stylistic integrity of the medieval works whenever repairs and restorations became necessary were largely abandoned in the sixteenth century. Often in the absence of any need to restore mosaics but under the sole pretense of replacing old mosaics with Renaissance and Mannerist ones, renowned artists such as Titian, Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Giuseppe Salviati, Palma Giovane increasingly competed for work in the church, preparing preliminary sketches for 'modern' mosaics, considered artistically superior, with little attempt to stylistically integrate the new figures and scenes into the older compositions.[161]

In addition to damage from fire and earthquake as well as from the vibrations that resulted whenever cannon were fired in salute from ships in the lagoon, the normal decay of the underlying masonry made it necessary to repeatedly repair the mosaics.[162] In 1716, Leopoldo dal Pozzo, a mosaicist from Rome, was commissioned to assume responsibility for the repair and maintenance of the mosaics in St Mark's, the local craftsmen having once again largely died out. Dal Pozzo also executed a few new mosaics based on preliminary drawings by Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and Sebastiano Ricci.[162] An exclusive contract for restoration was stipulated in 1867 with the mosaic workshop run by the Salviati glassmaking firm, whose highly criticized restoration work often involved removing and resetting the mosaics, usually with a considerable loss of quality. Although the original iconographic programme has been largely preserved, despite centuries of restoration and renewal, and roughly three-fourths of the mosaics maintain their earlier compositions and styles, only about a third can be considered original.[163]

Floor mosaics

The floor, executed primarily in opus sectile and to a lesser extent in opus tessellatum, dates to either the late eleventh century or first half of the twelfth century.[164] It consists of geometric patterns and animal designs made from a wide variety of coloured limestones and marbles.[165][166] The animals represented, including lions, eagles, griffons, deer, dogs, peacocks, and others, largely derive from medieval bestiaries and have symbolic meanings.[167]

Although it has similarities with Romanesque floors, the inclusion of large slabs of marble surrounded with decorative cornices also suggests an influence from eastern prototypes.[168][169] The frequent use of intertwined circles also recalls medieval Italian cosmatesque floors.[170]

Administration

Under the Venetian Republic, St Mark's was the private chapel of the Doge. The primicerius, responsible for the religious functions, was nominated by the Doge personally, and despite several attempts by the Bishop of Olivolo/Castello (after 1451 Patriarch of Venice) to claim jurisdiction over St Mark's, the primicerius remained subject to the Doge alone.[171][172]

Beginning in the ninth century, the Doge also nominated a procurator operis ecclesiae Sancti Marci, responsible for the financial administration of the church, its upkeep, and its decoration.[173] By the mid-thirteenth century there were two procurators in charge of the church, denominated de supra (Ecclesiam sancti Marci). Elected by the Great Council, they supervised the church in temporalibus, limiting the authority of the Doge. In 1442, there were three procurators de supra who administered the church and its treasury.[174][175] The procurators also hired and paid the proto, directly responsible for overseeing construction, maintenance, and restoration.[176]

St Mark's ceased to be the private chapel of the Doge as a result of the fall of the Republic of Venice to the French in 1797, and the primicerius was required to take an oath of office under the provisional municipal government. At that time, plans began to transfer the seat of the Patriarch of Venice from San Pietro di Castello to St Mark's.[177] However, no action was taken before Venice passed under Austrian control in 1798. During the first period of Austrian rule (1798–1805), it was alternatively suggested that the episcopal seat be moved to the Church of San Salvador, but again no action was taken until 1807 when, during the second period of French domination (1805–1814), St Mark's became the patriarchal cathedral. The new status was confirmed by Emperor Francis I of Austria in 1816 during the second period of Austrian rule (1814–1866) and by Pope Pius VII in 1821.[178]

See also

- Venetian School (music)

- Cappella Marciana

- List of buildings and structures in Venice

- List of churches in Venice

References

Notes

- ^ Wladimiro Dorigo alternatively hypothesizes that the Participizio church corresponded only to the crypt, including the section, now walled, under the central dome, which Dorigo interprets as the remains of an early westwork. See Wladimiro Dorigo, Venezia romanica..., I, pp. 20–21.

- ^ The current statues were carved by Girolamo Albanese in 1618 in substitution of the originals, destroyed in the earthquake of 1511. See Giulio Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 167

Citations

- ^ Touring Club Italiano, Venezia, p. 218

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 9

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 63

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 12

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 66

- ^ a b Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 28–29

- ^ Draghici-Vasilescu, 'The Church of San Marco...', pp. 713–714

- ^ a b Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 29

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 67

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 66, 68

- ^ Rendina, I dogi, p. 54

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 69–70

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 70

- ^ Parrot, The Genius of Venice, p. 37

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 71

- ^ a b Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 72

- ^ Dorigo, Venezia romanica..., I, p. 45

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 74

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, pp. 19–22

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 74, 88

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 74–75

- ^ Dodwell, The Pictorial arts of the West..., p. 184

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 75

- ^ Draghici-Vasilescu, 'The Church of San Marco...', p. 704, note 32

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 3

- ^ Messe proprie della Chiesa patriarcale di Venezia, Prot. CD 1165/52 (Venezia, Patriarcato di Venezia, 1983), pp. 74–77

- ^ Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice, p. 87

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 81

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 88–89

- ^ a b c Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 98

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 89

- ^ a b Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 99

- ^ a b Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 32

- ^ a b Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 6

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 101

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 120

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 33

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 34

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 88

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 83–87

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 76–82

- ^ a b Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 128

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 30

- ^ Piana, 'Le sovracupole lignee di San Marco', p. 189

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 103

- ^ Scarabello, Guida alla civiltà di Venezia, pp. 174–175

- ^ Piana, 'Le sovracupole lignee di San Marco', pp. 195–196

- ^ Jacoff, 'L'unità delle facciate di san Marco...', p. 78

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 110–111

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 114, 140–141, 147–148

- ^ a b c Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 184

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 183

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., pp. 164, 166, 168

- ^ Nelson, High Justice..., pp. 148–149

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., pp. 167–168

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 167

- ^ Jacoff, 'L'unità delle facciate di san Marco...', p. 84

- ^ Perry, 'Saint Mark's Trophies...', pp. 27–28

- ^ Vlad Borrelli, 'Ipotesi di datazione per i cavalli di San Marco', p. 39–42, 45

- ^ Perry, 'Saint Mark's Trophies...', p. 28

- ^ Touring Club Italiano, Venezia, p. 248

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 172

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 169

- ^ a b Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 112

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., pp. 167, 169–170

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 80

- ^ Lazzarini, 'Le pietre e i marmi colorati della basilica di San Marco a Venezia', pp. 318–319

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 79–80

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 113

- ^ Jacoff, 'L'unità delle facciate di san Marco...', p. 80

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 179–181

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 23

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 97

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 92–94

- ^ Bouras, 'Il tipo architettonico di san Marco', p. 170

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., pp. 183–184

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 183

- ^ Hopkins, 'Architecture and Infirmitas...', pp. 189–190

- ^ Howard, Sound and Space in Renaissance Venice..., p. 35

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 47–48

- ^ a b Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 184

- ^ Weigel, Thomas, Le colonne del ciborio dell'altare maggiore di san Marco a Venezia..., pp. 5–6

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., pp. 186–187

- ^ Klein, 'Refashioning Byzantium in Venice...', pp. 197–199

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 93

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 28, 96

- ^ 'Fabbriche antiche del quartiere marciano', pp. 46–55

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 28, 30–31, 33

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 39–40

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., pp. 189–191

- ^ Samerski, La Nikopeia..., pp. 9, 14

- ^ a b c Samerski, La Nikopeia..., p. 11

- ^ Samerski, La Nikopeia..., pp. 15–18

- ^ Belting, Likeness and presence..., pp. 203–204

- ^ Samerski, La Nikopeia..., p. 32

- ^ Tramontin, 'I santi dei mosaici marciani', p. 142

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 181

- ^ Tomasi, 'Prima, dopo, attorno la cappella...', pp. 16–17

- ^ Tomasi, 'Prima, dopo, attorno la cappella...', p. 15

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 43

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 191

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., pp. 181, 202

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, p. 79

- ^ Pincus, 'Geografia e politica nel battistero di san Marco...', p. 461, note 12

- ^ Pincus, 'Geografia e politica nel battistero di san Marco...', p. 461

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 207

- ^ Arcangeli, 'L'iconografia marciana nella sagrestia della Basilica di san Marco', pp. 227–228

- ^ Bergamo, 'Codussi, Spavento & co....', p. 90

- ^ Bergamo, 'Codussi, Spavento & co....', pp. 87–88

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, pp. 76–77

- ^ Wolters, 'San Marco e l'architettura del Rinascimento veneziano', p. 248

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, pp. 108, 114, 163

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 108

- ^ Wolters, 'San Marco e l'architettura del Rinascimento veneziano', pp. 249–250

- ^ Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, p. 121

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 87–88

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 20

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 21, 23

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 58

- ^ a b Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 89

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 49

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 50

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 53

- ^ Dodwell, The Pictorial arts of the West..., p. 186

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 201

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 90

- ^ a b Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 88

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 65

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 87

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 80, 82

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 123–126

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 91, 130–151

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 157, 159

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 156

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 155

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 175

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 155–156

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 164

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 165

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 159, 165

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 138–146

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 151

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 26, 61

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 18, 188

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 17–19

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 23, 188–189

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 5–6

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 25–26, 189

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 189–190

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 57, 190

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 193

- ^ Scarpa, 'La cappella dei Mascoli...', pp. 230, 232

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 190–191

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 60–61, 191

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 191

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 193–194, 199

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, pp. 6–7

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 193

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 7

- ^ Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario..., p. 203

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 8

- ^ a b Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 9

- ^ Demus, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice, p. 10

- ^ Farioli Campanata, 'Il pavimento di san Marco a Venezia...', p. 11

- ^ Farioli Campanata, 'Il pavimento di san Marco a Venezia', p. 12

- ^ Florent-Goudouneix, 'I pavimenti in «opus sectile» nelle chiese di Venezia e della laguna', p. 20

- ^ Barral I Altet, 'Genesi, evoluzione e diffusione dei pavimenti romanici', pp. 48–49

- ^ Farioli Campanata, 'Il pavimento di san Marco a Venezia...', pp. 12–13

- ^ Barral I Altet, 'Genesi, evoluzione e diffusione dei pavimenti romanici', p. 47

- ^ Farioli Campanata, 'Il pavimento di san Marco a Venezia', p. 14

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 44–45

- ^ Cozzi, 'Il giuspatronato del doge su san Marco', p. 731

- ^ Demus, The Church of San Marco in Venice, pp. 52–53

- ^ Tiepolo, Maria Francesca, 'Venezia', in La Guida generale degli Archivi di Stato, Archived 2021-06-04 at the Wayback Machine, IV (Roma: Ministero per i beni culturali e ambientali, Ufficio centrale per i beni archivistici, 1994), p. 886 ISBN 9788871250809

- ^ Da Mosto, Andrea, L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia, indice generale, storico, descrittivo ed analitico, Archived 2021-11-13 at the Wayback Machine (Roma: Biblioteca d'Arte editrice, 1937), p. 25

- ^ Howard, Jacopo Sansovino..., pp. 8–9

- ^ Scarabello, 'Il primiceriato di San Marco...', pp. 153–154

- ^ Scarabello, 'Il primiceriato di San Marco...', pp. 155–156

Bibliography

- Adami, Andrea and others, 'Image-based Techniques for the Survey of Mosaics in the St Mark's Basilica in Venice', Virtual Archaeology Review, 9(19) (2018), 1–20 ISSN 1989-9947

- Agazzi, Michela, Platea Sancti Marci: i luoghi marciani dall'11. al 13. secolo e la formazione della piazza (Venezia: Comune di Venezia, Assessorato agli affari istituzionali, Assessorato alla cultura and Università degli studi, Dipartimento di storia e critica delle arti, 1991) OCLC 889434590

- Agazzi, Michela, 'San Marco: Da cappella palatina a cripta contariana', in Manuela Zorzi, ed., Le cripte di Venezia: Gli ambienti di culto sommersi della cristianità medievale (Treviso: Chartesia, 2018), pp. 26–51 ISBN 9788899786151

- Barral I Altet, Xavier, 'Genesi, evoluzione e diffusione dei pavimenti romanici', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: i mosaici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 46–55 ISBN 8831768328

- Belting, Hans, Likeness and presence: a history of the image before the era of art, trans. by Edmund Jephcott (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994) ISBN 9780226042145

- Bergamo, Maria, 'Codussi, Spavento & co.: building the Sacristy of St Mark's Basilica in Venice', San Rocco Collaborations, 6 (Spring 2013), 86–96 ISSN 2038-4912

- Bernabei, Franco, 'Grottesco magnifico: fortuna critica di san Marco', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: l'architettura, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 207–234 ISBN 8831766457

- Betto, Bianca, 'La chiesa ducale', in Silvio Tramontin, ed., Patriarcato di Venezia, Storia Religiosa del Veneto (Padova: Gregoriana Libreria, 1991), pp. 333–366 ISBN 9788877060938

- Bouras, Charalambos, 'Il tipo architettonico di san Marco', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: l'architettura, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 164–175 ISBN 8831766457

- Cozzi, Gaetano, 'Il giuspatronato del doge su san Marco', in Antonio Niero, ed., San Marco: aspetti storici e agiografici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1996), pp. 727–742 ISBN 8831763695

- D'Antiga, Renato, 'Origini del culto marciano e traslazione delle reliquie a Venezia', Antichità Altoadriatiche, LXXV (2013), 221–241 ISSN 1972-9758

- Demus, Otto, The Church of San Marco in Venice: History, Architecture, Sculpture (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1960) OCLC 848981462

- Demus, Otto, The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco Venice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988) ISBN 0226142922

- Dodwell, Charles R., The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1993) ISBN 0300064934

- Dorigo, Wladimiro, 'Fabbriche antiche del quartiere marciano', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: l'architettura, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 39–66 ISBN 8831766457

- Dorigo, Wladimiro, Venezia romanica: la formazione della città medioevale fino all'età gotica, 2 vols (Venezia: Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, 2003) ISBN 9788883142031

- Draghici-Vasilescu, Elena Ene, 'The Church of San Marco in the [Byzantine] eleventh century', Mirabilia, 31/2 (2020), 695–740

- Farioli Campanata, Raffaela , 'Il pavimento di san Marco a Venezia e i suoi rapporti con l'Oriente', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: i mosaici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 11–19 ISBN 8831768328

- Fedalto, Giorgio, 'San Marco tra Babilonia, Roma e Aquileia: nuove ipotesi e ricerche', in Antonio Niero, ed., San Marco: aspetti storici e agiografici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1996), pp. 35–50 ISBN 8831763695

- Florent-Goudouneix, Yvette, 'I pavimenti in «opus sectile» nelle chiese di Venezia e della laguna', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: i mosaici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 20–29 ISBN 8831768328

- Geary, Patrick J., Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978) ISBN 9780691052618

- Hopkins, Andrew, 'Architecture and Infirmitas: Doge Andrea Gritti and the Chancel of San Marco', Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 57.2 (June 1998), 182–197 ISSN 0037-9808

- Howard, Deborah, The Architectural History of Venice (London: B. T. Batsford, 1980) ISBN 9780300090291

- Howard, Deborah, Jacopo Sansovino: architecture and patronage in Renaissance Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975) ISBN 9780300018912

- Howard, Deborah and Laura Moretti, Sound and Space in Renaissance Venice: architecture, music, acoustics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009) ISBN 9780300148749

- Jacoff, Michael, 'L'unità delle facciate di san Marco del XIII secolo', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: l'architettura, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 77–87 ISBN 8831766457

- Klein, Holger A., 'Refashioning Byzantium in Venice, ca. 1200–1400', in Henry Maguire and Robert S. Nelson, ed., San Marco, Byzantium, and the Myths of Venice, (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, 2010) pp. 193–226 ISBN 9780884023609

- Lazzarini, Lorenzo, 'Le pietre e i marmi colorati della basilica di San Marco a Venezia', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: l'architettura, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 309–328 ISBN 8831766457

- Lorenzetti, Giulio, Venezia e il suo estuario: guida storico-artistico (Venezia: Bestetti & Tumminelli, 1926; repr. Trieste: Lint, 1974-1994) OCLC 878738785

- Morelli, Arnaldo, 'Concorsi organistici a san Marco e in area veneta nel Cinquecento', in Francesco Passadore and Franco Rossi, ed., La cappella musicale di San Marco nell'età moderna, Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia, Palazzo Giustinian Lolin, 5–7 settembre 1994 (Venezia: Edizioni Fondazione Levi, 1998), pp. 259–278 ISBN 9788875520182

- Moretti, Laura, 'Architectural Spaces for Music: Jacopo Sansovino and Adrian Willaert at St Mark's', Early Music History, 23 (2004), 153–184 ISSN 0261-1279

- Muir, Edward, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981) ISBN 0691102007

- Nelson, Robert S., 'High Justice: Venice, San Marco, and the Spoils of 1204', in Panayotis L. Vocotopoulos, ed., Byzantine Art in the Aftermath of the Fourth Crusade: the Fourth Crusade and Its Consequences, Acts of the International Congress, Athens 9–12 March 2004 (Athens: Academy of Athens, Research Centre for Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Art, 2007), pp. 143–151 ISBN 9789604041114

- Nicol, Donald M., Byzantium and Venice: a study in diplomatic and cultural relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988) ISBN 0521341574

- Parrot, Dial, The Genius of Venice: Piazza San Marco and the Making of the Republic (New York: Rizzoli, 2013) ISBN 9780847840533

- Perry, Marilyn, 'Saint Mark's Trophies: Legend, Superstition, and Archaeology in Renaissance Venice', Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 40 (1977), 27–49 ISSN 0075-4390

- Piana, Mario, 'Le sovracupole lignee di San Marco', in Ettore Vio, ed., San Marco, la Basilica di Venezia: arte, storia, conservazione, vol. 1 (Venezia: Marsilio, 2019), pp. 189–200 OCLC 1110869334

- Pincus, Debra, 'Geografia e politica nel battistero di san Marco: la cupola degli apostoli', in Antonio Niero, ed., San Marco: aspetti storici e agiografici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1996), pp. 459–473 ISBN 8831763695

- Rendina, Claudio, I dogi: storia e segreti (Roma: Newton, 1984) ISBN 9788854108172

- Rosand, David, Myths of Venice: the Figuration of a State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) ISBN 0807826413

- Samerski, Stefan, La Nikopeia: immagine di culto, Palladio, mito veneziano (Roma: Viella, 2012) ISBN 9788883347016

- Scarabello, Giovanni, 'Il primiceriato di San Marco tra la fine della Repubblica e la soppressione', in Antonio Niero, ed., San Marco: aspetti storici e agiografici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1996), pp. 152–160 ISBN 8831763695

- Scarabello, Giovanni and Paolo Morachiello, Guida alla civiltà di Venezia (Milano: Mondadori, 1987) ISBN 9788804302018

- Scarpa, Giulia Rossi, 'La cappella dei Mascoli: il trionfo dell'architettura', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: i mosaici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 222–234 ISBN 8831768328

- Schmidt Arcangeli, Catarina, 'L'iconografia marciana nella sagrestia della Basilica di san Marco', in Antonio Niero, ed., San Marco: aspetti storici e agiografici, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1996), pp. 223–239 ISBN 8831763695

- Tomasi, Michele, 'Prima, dopo, attorno la cappella: il culto di Sant'Isidoro a Venezia', in La cappella di Sant'Isidoro, Quaderni della Procuratoria: arte, storia, restauri della Basilica di san Marco a Venezia, Anno 2008 (Venezia: Procuratoria di san Marco, 2008) OCLC 878712543

- Touring Club Italiano, ed., Venezia, 3rd edn (Milano: Touring Club Italiano, 1985) ISBN 9788836500062

- Tramontin, Silvio, 'I santi dei mosaici marciani', in Culto dei Santi a Venezia (Venezia: Studium Cattolico Veneziano, 1965), pp. 133–154 OCLC 799322387

- Tramontin, Silvio, 'San Marco', in Culto dei Santi a Venezia (Venezia: Studium Cattolico Veneziano, 1965), pp. 41–74 OCLC 799322387

- Veludo, Giovanni, La Pala d'oro della Basilica di San Marco in Venezia (Venezia: F. Ongania, 1887)

- Vianello, Sabina, Le chiese di Venezia (Milano, Electa, 1993) ISBN 9788843540488

- Vio, Ettore, Lo splendore di san Marco (Rimini: Idea, 2001) ISBN 9788870827279

- Vlad Borrelli, Licia, 'Ipotesi di datazione per i cavalli di San Marco', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: sculture, tesoro, arazzi, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 34–49 ISBN 8831768522

- Warren, John, 'La prima chiesa di san Marco Evangelista a Venezia', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: l'architettura, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 184–200 ISBN 8831766457

- Weigel, Thomas, Le colonne del ciborio dell'altare maggiore di san Marco a Venezia: nuovi argomenti a favore di una datazione in epoca protobizantina, Quaderni - Centro tedesco di studi veneziani, 54, (Venezia: Centro tedesco di studi veneziani, 2000) ISBN 9783799547543

- Wolters, Wolfgang, 'San Marco e l'architettura del Rinascimento veneziano', in Renato Polacco, ed., Storia dell'arte marciana: l'architettura, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia 11–14 ottobre 1994 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), pp. 248–254 ISBN 8831766457

- Zatta, Antonio, Basilica di San Marco (Gregg Press, 1964), reprinted from the original edition of 1761

External links

- Official website

- Satellite image from Google Maps

- The Nicopeia Icon of San Marco

St Mark's Basilica travel guide from Wikivoyage

St Mark's Basilica travel guide from Wikivoyage

| Preceded by Santi Giovanni e Paolo |

Venice landmarks St Mark's Basilica |

Succeeded by Venetian Arsenal |