Akka Mahadevi: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Tharu and Lalita also document a claim that a local [[Jainism|Jain]] king named Kaushika sought to marry her, but that she rejected him, choosing instead to fulfil the claims of devotion to the deity Para [[Shiva]].<ref name=":0" /> However, the medieval sources that form the basis of this account are ambiguous and inconclusive.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last=Ramaswamy|first=Vijaya|date=1992-01-01|title=Rebels — Conformists? Women Saints in Medieval South India|jstor=40462578|journal=Anthropos|volume=87|issue=1/3|pages=133–146}}</ref> They include a reference to one of her poems, or ''vachanas'', in which she lays down three conditions for marrying the king, including control over the choice to spend her time in devotion or in conversation with other scholars and religious figures, rather than with the king.<ref name=":3" /> The medieval scholar and poet Harihara suggests in his biography of her that the marriage was purely nominal, while other accounts from Camasara suggest that the conditions were not accepted and the marriage did not occur.<ref name=":3" /> |

Tharu and Lalita also document a claim that a local [[Jainism|Jain]] king named Kaushika sought to marry her, but that she rejected him, choosing instead to fulfil the claims of devotion to the deity Para [[Shiva]].<ref name=":0" /> However, the medieval sources that form the basis of this account are ambiguous and inconclusive.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last=Ramaswamy|first=Vijaya|date=1992-01-01|title=Rebels — Conformists? Women Saints in Medieval South India|jstor=40462578|journal=Anthropos|volume=87|issue=1/3|pages=133–146}}</ref> They include a reference to one of her poems, or ''vachanas'', in which she lays down three conditions for marrying the king, including control over the choice to spend her time in devotion or in conversation with other scholars and religious figures, rather than with the king.<ref name=":3" /> The medieval scholar and poet Harihara suggests in his biography of her that the marriage was purely nominal, while other accounts from Camasara suggest that the conditions were not accepted and the marriage did not occur.<ref name=":3" /> |

||

Harihara's account goes on to say that when King Kaushika violated the conditions she had laid down, Akka Mahadevi left the palace, renouncing all her possessions including clothes, to travel to Srisailam, home of the god |

Harihara's account goes on to say that when King Kaushika violated the conditions she had laid down, Akka Mahadevi left the palace, renouncing all her possessions including clothes, to travel to Srisailam, home of the god Parama [[Shiva]].<ref name=":3" /> Alternative accounts suggest that Akka Mahadevi's act of renunciation was a response to the king's threats after she refused his proposal.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Michael|first=R. Blake|date=1983-01-01|title=Women of the Śūnyasaṃpādane: Housewives and Saints in Vīraśaivism|jstor=601458|journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society|volume=103|issue=2|pages=361–368|doi=10.2307/601458}}</ref> It is likely that she visited the town of Kalyana en route, where she met two other poets and prominent figures of the [[Lingayat]] movement, [[Allama Prabhu|Allama]] and [[Basava]].<ref name=":0" /> She is believed to have travelled, towards the end of her life, to the Srisailam mountains, where she lived as an ascetic and eventually died.<ref name=":0" /> A ''vachana'' attributed to Akka Mahadevi suggests that towards the end of her life King Kaushika visited her there, and sought her forgiveness.<ref name=":3" /> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 09:36, 5 March 2024

Akka Mahadevi (Kannada: ಅಕ್ಕ ಮಹಾದೇವಿ, c. 1130–1160) was one of the early poets of Kannada literature[1] and a prominent person in the Lingayat Shaiva sect in the 12th century.[2] Her 430 Vachana poems (a form of spontaneous mystical poems), and the two short writings called Mantrogopya and the Yogangatrividh are considered her known contributions to Kannada literature.[3] She composed fewer poems than other saints of the movement. The term Akka ("elder Sister" or "mother") is an honorific given to her by saints such as Basavanna, Siddharama and Allamaprabhu and an indication of her high place in the spiritual discussions held at the "Anubhava Mantapa".[4] She is seen as an inspirational woman in Kannada literature and in the history of Karnataka. She considered the god Shiva ('Chenna Mallikarjuna') as her husband, (traditionally understood as the 'madhura bhava' or 'madhurya' form of devotion).[citation needed]

Biography

Akka Mahadevi was born in Udutadi, near Shivamogga in the Indian state of the Karnataka[5] around 1130.[6] Some scholars suggest that she was born to a couple named Nirmalshetti and Sumati, who were both devotees of ParamaShiva.[7] Western sources claim that little is known about her life, though it has been the subject of Indian hagiographic, folk and mythological claims, based on oral tradition and her own lyrics. One of her lyrics, for instance, appears to record her experiences of leaving her place of her birth and family in order to pursue Shiva.[5]

Tharu and Lalita also document a claim that a local Jain king named Kaushika sought to marry her, but that she rejected him, choosing instead to fulfil the claims of devotion to the deity Para Shiva.[5] However, the medieval sources that form the basis of this account are ambiguous and inconclusive.[8] They include a reference to one of her poems, or vachanas, in which she lays down three conditions for marrying the king, including control over the choice to spend her time in devotion or in conversation with other scholars and religious figures, rather than with the king.[7] The medieval scholar and poet Harihara suggests in his biography of her that the marriage was purely nominal, while other accounts from Camasara suggest that the conditions were not accepted and the marriage did not occur.[7]

Harihara's account goes on to say that when King Kaushika violated the conditions she had laid down, Akka Mahadevi left the palace, renouncing all her possessions including clothes, to travel to Srisailam, home of the god Parama Shiva.[7] Alternative accounts suggest that Akka Mahadevi's act of renunciation was a response to the king's threats after she refused his proposal.[9] It is likely that she visited the town of Kalyana en route, where she met two other poets and prominent figures of the Lingayat movement, Allama and Basava.[5] She is believed to have travelled, towards the end of her life, to the Srisailam mountains, where she lived as an ascetic and eventually died.[5] A vachana attributed to Akka Mahadevi suggests that towards the end of her life King Kaushika visited her there, and sought her forgiveness.[7]

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2015) |

She is considered by modern scholars to be a prominent figure in the field of female emancipation. A household name in Karnataka, she wrote that she was a woman only in name and that her mind, body, and soul belonged to Shiva. During a time of strife and political uncertainty in the 12th century, she chose spiritual enlightenment and stood by her choice. She took part in convocations of the learned such as the Anubhavamantapa in Kalyana (now Basava Kalyana) to debate philosophy and enlightenment (or Moksha, termed by her as "arivu"). In search for her soul mate Lord Shiva, she made animals, flowers and birds her friends and companions, rejecting family life and worldly attachment.

Akka's pursuit of enlightenment is recorded in poems of simple language but intellectual rigour. Her poetry explores the rejection of mortal love in favour of the love of God. Her vachanas also talk about the methods that the path of enlightenment demand of the seeker, such as killing the 'I', conquering desires and the senses and so on.

Kausika belonged to the Jain community, that was wealthy and resented by the rest of the population. She rejected her life of luxury to live as a wandering poet-saint, travelling throughout the region and singing praises to her Lord Shiva. She went in search of fellow seekers or sharanas because the company of the saintly or sajjana sanga is believed to hasten learning. She found the company of such sharanas in Basavakalyana, Bidar district and composed many vachanas in praise of them. Her non-conformist ways caused consternation in the conservative society of the time: even her guru Allama Prabhu faced difficulties in including her in the gatherings at Anubhavamantapa.

An ascetic, Mahadevi is said to have refused to wear any clothing. Legend has it that due to her true love and devotion with God her whole body was protected by hair.

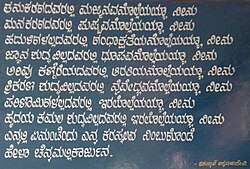

All the sharnas of Anubhavamantapa, especially Basavanna, Chenna Basavanna, Kinnari Bommayya, Siddharama, Allamaprabhu and Dasimayya greet her with a word "Akka". In fact it is here onwards that she becomes Akka, an elderly sister. Allama shows her the further way of attaining the transcendent bliss of union with Lord Chenna Mallikarjuna. Akka leaves Kalyana with this following vachana:

Having vanquished the six passions and become

The trinity of body, thought and speech;

Having ended the trinity and become twain – I and the Absolute

Having ended the duality and become a unity

Is because of the grace of you all.

I salute Basavanna and all assembled here

Blessed was I by Allama my Master-

Bless me all that I may join my Chenna Mallikarjuna

Good-bye! Good-bye!

In the first phase of her life she renounced worldly objects and attractions; in the second, she discarded all object-based rules and regulations. In the third phase she began her journey towards Srishila, location of the temple to Chenna Mallikarjuna and a holy place for devotees of Shiva since before the 12th century. Akka's spiritual journey ended at Kadali, the thick forest area of Shrisaila (Srisailam) where she is supposed to have experienced union (aikya) with Chennamallikarjuna.

One of her famous vachana translates as:

People,

male and female,

blush when a cloth covering their shame

comes loose

When the lord of lives

lives drowned without a face

in the world, how can you be modest?

When all the world is the eye of the lord,

onlooking everywhere, what can you

cover and conceal?

Her poetry exhibits her love for Chenna Mallikarjuna, and harmony with nature and simple living.

She sang:

For hunger, there is the village rice in the begging bowl,

For thirst, there are tanks and streams and wells

For sleep temple ruins do well

For the company of the soul I have you, Chenna Mallikarjuna

Works

Akka Mahadevi's works, like many other Bhakti movement poets, can be traced through the use of her ankita, or the signature name by which she addressed the figure of her devotion.[10] In Akka Mahadevi's case, she uses the name Chennamallikarjuna to refer to the god Shiva.[10] The name Chennamallikarjuna can be variously translated, but the most well-known translation is by the scholar and linguist A.K. Ramanujan, who interprets it as 'Lord, white as jasmine'.[10] A more literal translationn would be 'Mallika's beautiful Arjuna', according to Tharu and Lalita.[5]

Based on the use of her ankita, about 350 lyric poems or vachanas are attributed to Akka Mahadevi.[11] Her works frequently use the metaphor of an illicit, or adulterous love to describe her devotion to Chennamallikarjuna (Shiva).[11] The lyrics show Akka Mahadevi actively seeking a relationship with Chennamallikarjuna (Shiva), and touches on themes of abandonment, carnal love and separation.[11]

The direct and frank lyrics that Akka Mahadevi wrote have been described as embodying a "radical illegitimacy" that re-examines the role of women as actors with volition and will, behaving in opposition to established social institutions and mores.[11] At times she uses strong sexual imagery to represent the union between the devotee and the object of devotion.[12] Her works challenge common understandings of sexual identity; for instance, in one vachana she suggests that creation, or the power of the god Shiva, is masculine, while all of creation, including men, represent the feminine: "I saw the haughty master, Mallikarjuna/for whom men, all men, are but women, wives".[8] In some vachanas, she describes herself as both feminine and masculine.[8]

Akka Mahadevi's works, like those of many other female Bhakti poets, touch on themes of alienation: both from the material world, and from social expectations and mores concerning women.[8] Seeing relationships with mortal men as unsatisfactory, Akka Mahadevi describes them as thorns hiding under smooth leaves, untrustworthy. About her mortal husband she says "Take these husbands who die, decay - and feed them to your kitchen fires!". In another verse, she expresses the tension of being a wife and a devotee as

Husband inside, lover outside.

I can't manage them both.

This world and that other, cannot manage them both.[13]

Translations and legacy

A. K. Ramanujan first popularised the vachanas by translating them into a collection called Speaking of Siva. Postcolonial scholar Tejaswini Niranjana criticised these translations as rendering the vachanas into modern universalist poetry ready-to-consume by the West in Siting Translation (1992).[citation needed][14] Kannada translator Vanamala Vishwanatha is currently working on a new English translation, which may be published as part of the Murty Classical Library.[15]

Akka Mahadevi continues to occupy a significant place in culture and memory, with roads[16] and universities named after her.[17] In 2010, a bas relief dating to the 13th century was discovered near Hospet in Karnataka, and is believed to be a depiction of Akka Mahadevi.

References

- ^ Hipparagi, Abhijit (30 July 2013). "Interesting Facts About Karnataka: Kannada's First". Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ banajiga debate "Making Sense of the Lingayat vs Veerashaiva Debate".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Biography of a mystic poet". The Hindu. 26 September 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ Mudde, Raggi (23 September 2011). "An Epitome of Feminism - Akka Mahadevi". Karnataka.com. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Tharu, Susie J.; Lalita, Ke (1 January 1991). Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the early twentieth century. Feminist Press at CUNY. p. 78. ISBN 9781558610279.

- ^ "A pleasant surprise for the people". The Hindu. 22 March 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ a b c d e Mudaliar, Chandra Y (1 January 1991). "Religious Experiences of Hindu Women: A Study of Akka Mahadevi". Mystics Quarterly. 17 (3): 137–146. JSTOR 20717064.

- ^ a b c d Ramaswamy, Vijaya (1 January 1992). "Rebels — Conformists? Women Saints in Medieval South India". Anthropos. 87 (1/3): 133–146. JSTOR 40462578.

- ^ Michael, R. Blake (1 January 1983). "Women of the Śūnyasaṃpādane: Housewives and Saints in Vīraśaivism". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 103 (2): 361–368. doi:10.2307/601458. JSTOR 601458.

- ^ a b c Tharu, Susie J.; Lalita, Ke (1 January 1991). Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the early twentieth century. Feminist Press at CUNY. p. 58. ISBN 9781558610279.

- ^ a b c d Tharu, Susie J.; Lalita, Ke (1 January 1991). Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the early twentieth century. Feminist Press at CUNY. p. 79. ISBN 9781558610279.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Vijaya (1 January 1996). "Madness, Holiness, Poetry : The Vachanas Of Virasaivite Women". Indian Literature. 39 (3 (173)): 147–155. JSTOR 23336165.

- ^ Chakravarty, Uma (1989). "The World of the Bhaktin in South Indian Traditions - The Body and Beyond" (PDF). Manushi. 50-51-52: 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ Siting Translation. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Lively debate marks launch of Kannada classic in Harvard series". Deccan Herald. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Staff Correspondent. "Junction in Shivamogga named after Akka Mahadevi". The Hindu. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Women's university renamed - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

External links

- "Songs of Shiva Akka Mahadevi" translated by Vinaya Chaitanya

- Lingayatism

- History of Karnataka

- Lingayat poets

- Kannada poets

- Indian women poets

- 12th-century women writers

- 12th-century writers

- 12th-century births

- 12th-century deaths

- 12th-century Indian philosophers

- Indian women philosophers

- Bhakti movement

- People from Shimoga

- Kannada people

- Hindu female religious leaders

- 12th-century Indian poets

- Poets from Karnataka

- 12th-century Indian writers

- Women writers from Karnataka

- Kannada-language writers

- 12th-century Indian women

- 12th-century Indian people

- Ancient Indian women writers

- Ancient Asian women writers

- Ancient Indian writers

- Lingayat saints

- Scholars from Karnataka

- Women mystics