Theoretical key: Difference between revisions

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

== Etc. == |

== Etc. == |

||

* There is also an example of modulation in John Stump's Prelude and the Last Hope with a [[double flat]] in the [[key signature]].<ref>[https://www.flickr.com/photos/heatherlewin/6951090591]</ref> <score>{ \omit Score.TimeSignature { \omit Staff.KeyCancellation \set Staff.keyAlterations = #`((6 . ,DOUBLE-FLAT)(2 . ,DOUBLE-FLAT)(5 . ,DOUBLE-FLAT)(1 . ,FLAT)(4 . ,FLAT)(0 . ,FLAT)(3 . ,FLAT)) s^""}}</score>However, when using the tonality of this [[key signature]], the [[Measure (music)|measure]] is merely a measure of whole rests and no note at all. |

* There is also an example of modulation in John Stump's Prelude and the Last Hope with a [[double flat]] in the [[key signature]].<ref>[https://www.flickr.com/photos/heatherlewin/6951090591]</ref> <score>{ \omit Score.TimeSignature { \omit Staff.KeyCancellation \set Staff.keyAlterations = #`((6 . ,DOUBLE-FLAT)(2 . ,DOUBLE-FLAT)(5 . ,DOUBLE-FLAT)(1 . ,FLAT)(4 . ,FLAT)(0 . ,FLAT)(3 . ,FLAT)) s^""}}</score>However, when using the tonality of this [[key signature]], the [[Measure (music)|measure]] is merely a measure of whole rests and no note at all. |

||

* Going further theoretically, there may be countless such keys<ref>In other words, the '''theoretical keys''' can include not only the [[ |

* Going further theoretically, there may be countless such keys<ref>In other words, the '''theoretical keys''' can include not only the [[double accidentals]] but also after [[triple accidentals]] ([[triple flat]]/[[triple sharp]]).</ref>, and there may be other considerations as well. For reference, in [[equal temperament]] with [[enharmonics]], [[Enharmonic key signature|enharmonic keys]] can exist, but in the [[Just Intonation|just intonation]], there are no [[Enharmonic key signature|enharmonic keys]].<ref>For example, when considering [[Enharmonic key signature|enharmonic keys]], there is a simplest or most appropriate notation for each note. In addition, in ''n''-[[Equal temperament|TET]], which divides an [[octave]] into ''n-''equal parts, the [[Pitch (music)|pitches]] of [[Major (music)|major]] or [[Minor (music)|minor]] [[Key (music)|keys]] are limited to a total of ''n''-types per [[octave]], regardless of whether they are [[microtones]] or '''theoretical keys'''. For example, there will be 12 types in [[12 TET]] and 19 types in [[19 TET]].</ref> |

||

* Some ask 'Why is there no [[G sharp major]]?', 'Why is there no [[D flat minor]]?' etc. have also been recognized.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} These keys are exactly the '''theoretical keys'''. |

* Some ask 'Why is there no [[G sharp major]]?', 'Why is there no [[D flat minor]]?' etc. have also been recognized.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} These keys are exactly the '''theoretical keys'''. |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 05:20, 7 March 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2018) |

In music theory, a theoretical key is a key whose key signature would have at least one double-flat (![]() ) or double-sharp (

) or double-sharp (![]() ).

).

Some musical keys are not normally used because they would require a double sharp or double flat in the key signature. For example, G♯ major requires eight sharps, and, since there are only seven scale tones, one tone requires a double sharp. The enharmonically equivalent key of A♭ only requires four flats, making it clearer to read.

Enharmonic equivalence

|

|

| G♯ major, a key signature with a double-sharp | A♭ major, equivalent key |

| G♯ major: | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F |

| A♭ major: | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G |

The key of G♯ major is a theoretical key because its key signature has an F![]() , giving it eight sharps. An equal-tempered scale in G♯ major contains the same pitches as the A♭ major scale, making the two keys enharmonically equivalent. In the absence of other factors, this key would generally be notated as A♭ major.

, giving it eight sharps. An equal-tempered scale in G♯ major contains the same pitches as the A♭ major scale, making the two keys enharmonically equivalent. In the absence of other factors, this key would generally be notated as A♭ major.

Modulation

While a piece of Western music generally has a home key, a passage within it may modulate to another key, which is usually closely related to the home key (in the Baroque and early Classical eras), that is, close to the original in the circle of fifths. When the key has zero or few sharps or flats, the notation of both keys is straightforward. But if the home key has many sharps or flats, particularly if the new key is on the opposite side, double sharps or flats may be necessary, or an enharmonically equivalent key may be used to avoid double sharps or flats.

In the bottom three places on the circle of fifths the enharmonic equivalents can be notated with single sharps or flats and so are not theoretical keys:

| Major (minor) | Key signature | Major (minor) | Key signature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (g♯) | 5 sharps | C♭ (a♭) | 7 flats | |

| F♯ (d♯) | 6 sharps | G♭ (e♭) | 6 flats | |

| C♯ (a♯) | 7 sharps | D♭ (b♭) | 5 flats |

The need to consider theoretical keys

When a parallel key ascends the opposite side of the circle from its home key, theory suggests that double-sharps and double-flats would have to be incorporated into the notated key signature. The following theoretical keys would require up to seven double-sharps or double-flats. Six of these are the parallel major/minor keys of those above.

| Major | Key signature | Minor |

|---|---|---|

| F♭ major (E major) | 8 flats (4 sharps) | D♭ minor (C♯ minor) |

| B |

9 flats (3 sharps) | G♭ minor (F♯ minor) |

| E |

10 flats (2 sharps) | C♭ minor (B minor) |

| A |

11 flats (1 sharp) | F♭ minor (E minor) |

| D |

12 flats (no flats or sharps) | B |

| G |

13 flats (1 flat) | E |

| C |

14 flats (2 flats) | A |

| G♯ major (A♭ major) | 8 sharps (4 flats) | E♯ minor (F minor) |

| D♯ major (E♭ major) | 9 sharps (3 flats) | B♯ minor (C minor) |

| A♯ major (B♭ major) | 10 sharps (2 flats) | F |

| E♯ major (F major) | 11 sharps (1 flat) | C |

| B♯ major (C major) | 12 sharps (no flats or sharps) | G |

| F |

13 sharps (1 sharp) | D |

| C |

14 sharps (2 sharps) | A |

A piece in a major key might modulate up a fifth to the dominant (a common occurrence in Western music), resulting in a new key signature with an additional sharp. If the original key was C-sharp, such a modulation would lead to the theoretical key of G-sharp major (with eight sharps) requiring an F![]() in place of the F♯. This section could be written using the enharmonically equivalent key signature of A-flat major instead. Claude Debussy's Suite bergamasque does this: in the third movement "Clair de lune" the key shifts from D-flat major to D-flat minor (eight flats) for a few measures but the passage is notated in C-sharp minor (four sharps); the same happens in the final movement, "Passepied", in which a G-sharp major section is written as A-flat major.

in place of the F♯. This section could be written using the enharmonically equivalent key signature of A-flat major instead. Claude Debussy's Suite bergamasque does this: in the third movement "Clair de lune" the key shifts from D-flat major to D-flat minor (eight flats) for a few measures but the passage is notated in C-sharp minor (four sharps); the same happens in the final movement, "Passepied", in which a G-sharp major section is written as A-flat major.

Such passages may instead be notated with the use of double-sharp or double-flat accidentals, as in this example from Johann Sebastian Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, which has this passage in G-sharp major in measures 10-12.

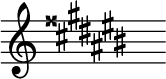

In very few cases, theoretical keys are used directly, with the necessary double-accidentals in the key signature. The final pages of John Foulds' A World Requiem are written in G♯ major (with F![]() in the key signature), No. 18 of Anton Reicha's Practische Beispiele is written in B♯ major, and the third movement of Victor Ewald's Brass Quintet Op. 8 is written in F♭ major (with B

in the key signature), No. 18 of Anton Reicha's Practische Beispiele is written in B♯ major, and the third movement of Victor Ewald's Brass Quintet Op. 8 is written in F♭ major (with B![]() in the key signature).[1][2] Examples of theoretical key signatures are pictured below:

in the key signature).[1][2] Examples of theoretical key signatures are pictured below:

There does not appear to be a standard on how to notate theoretical key signatures:

- The default behaviour of LilyPond (pictured above) writes all single signs in the circle-of-fifths order, before proceeding to the double signs. This is the format used in John Foulds' A World Requiem, Op. 60, which ends with the key signature of G♯ major exactly as displayed above.[3] The sharps in the key signature of G♯ major here proceed C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, F

. This likely makes more sense than the last example because the notes represented in the key signature increase by a perfect fifth (or decrease by a perfect fourth) from left to right.

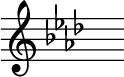

. This likely makes more sense than the last example because the notes represented in the key signature increase by a perfect fifth (or decrease by a perfect fourth) from left to right. - The single signs at the beginning are sometimes repeated as a courtesy, e.g. Max Reger's Supplement to the Theory of Modulation, which contains D♭ minor key signatures on pp. 42–45.[4] These have a B♭ at the start and also a B

at the end (with a double-flat symbol), going B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, B

at the end (with a double-flat symbol), going B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, B .

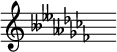

. - Sometimes the double signs are written at the beginning of the key signature, followed by the single signs. For example, the F♭ key signature is notated as B

, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭. This convention is used by Victor Ewald[5] and by some theoretical works.

, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭. This convention is used by Victor Ewald[5] and by some theoretical works. - However, no. 18 of Anton Reicha's Practische Beispiele in B♯ major,[1] it was written as B♯, E♯, A

, D

, D , G

, G , C

, C , F

, F .

.

Tunings other than twelve-tone equal-temperament

Tuning systems where the number of notes per octave is not a multiple of 12 can produce key signatures that have no equivalent in 12-tone equal temperament, in which case double-sharps, double-flats, or microtonal accidentals will be required. Additionally, keys such as G♯ major and F♭ major which 12-tone equal temperament and its multiples make redundant are distinguished in other tunings, and therefore, must be notated completely differently. For example, in 19-tone equal temperament, the key of A♯ major has 10 sharps, and is enharmonically equivalent to B![]() major, which has nine flats.

major, which has nine flats.

Etc.

- There is also an example of modulation in John Stump's Prelude and the Last Hope with a double flat in the key signature.[6] However, when using the tonality of this key signature, the measure is merely a measure of whole rests and no note at all.

- Going further theoretically, there may be countless such keys[7], and there may be other considerations as well. For reference, in equal temperament with enharmonics, enharmonic keys can exist, but in the just intonation, there are no enharmonic keys.[8]

- Some ask 'Why is there no G sharp major?', 'Why is there no D flat minor?' etc. have also been recognized.[citation needed] These keys are exactly the theoretical keys.

See also

- Closely related key – Musical keys sharing many common tones

- Diatonic function – Musical term

References

- ^ a b Anton Reicha: Practische Beispiele, pp. 52-53.: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ "Ewald, Victor: Quintet No 4 in A♭, op 8". imslp. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ John Foulds: A World Requiem, pp. 153ff.: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ Max Reger (1904). Supplement to the Theory of Modulation. Translated by John Bernhoff. Leipzig: C. F. Kahnt Nachfolger. pp. 42–45.

- ^ "Ewald, Victor: Quintet No 4 in A♭, op 8", Hickey's Music Center

- ^ [1]

- ^ In other words, the theoretical keys can include not only the double accidentals but also after triple accidentals (triple flat/triple sharp).

- ^ For example, when considering enharmonic keys, there is a simplest or most appropriate notation for each note. In addition, in n-TET, which divides an octave into n-equal parts, the pitches of major or minor keys are limited to a total of n-types per octave, regardless of whether they are microtones or theoretical keys. For example, there will be 12 types in 12 TET and 19 types in 19 TET.