Dennis Wilson: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

In January 1981, Brian's then-girlfriend and nurse Carolyn Williams accused Dennis of enticing Brian to purchase about $15,000 worth of cocaine. When Brian's bodyguard [[Rocky Pamplin]] and the Wilsons' cousin [[Stan Love (basketball)|Stan Love]] learned of this incident, they physically assaulted Dennis at his home. For the assault, they were fined about $1,000, and Dennis filed a restraining order.<ref>{{cite web|title=Beach Boy drummer 'goes for it' and ends up beat up|publisher=The Spokesman-Review Spokane Chronicle|first=Steven|last=Gaines|author-link=Steven Gaines|date=October 21, 1986|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1314&dat=19861021&id=7TwVAAAAIBAJ&pg=7039,3470164|ref=none}}</ref> |

In January 1981, Brian's then-girlfriend and nurse Carolyn Williams accused Dennis of enticing Brian to purchase about $15,000 worth of cocaine. When Brian's bodyguard [[Rocky Pamplin]] and the Wilsons' cousin [[Stan Love (basketball)|Stan Love]] learned of this incident, they physically assaulted Dennis at his home. For the assault, they were fined about $1,000, and Dennis filed a restraining order.<ref>{{cite web|title=Beach Boy drummer 'goes for it' and ends up beat up|publisher=The Spokesman-Review Spokane Chronicle|first=Steven|last=Gaines|author-link=Steven Gaines|date=October 21, 1986|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1314&dat=19861021&id=7TwVAAAAIBAJ&pg=7039,3470164|ref=none}}</ref> |

||

As the Beach Boys pressured Brian to readmit himself into [[Eugene Landy]]'s 24-hour therapy program, Dennis was informed by friends that he would be the band's next target, to Dennis's disbelief.<ref name=Goldberg1984 /> |

As the Beach Boys pressured Brian to readmit himself into [[Eugene Landy]]'s 24-hour therapy program, Dennis was informed by friends that he would be the band's next target, to Dennis's disbelief.<ref name=Goldberg1984 /> His disbelief was proven wrong as the rest of the band gave him an ultimatum after his last performance in September 1983 to check into rehab for his alcohol problems or be banned from performing live with them.<ref name=Goldberg1984 /> By then, he was homeless and living a [[nomadic]] life.<ref name=Goldberg1984 /> He checked into a therapy center in Arizona for two days, and then on December 23, 1983, checked into St. John's Hospital in Santa Monica, where he stayed until the evening of December 25. Following a violent altercation at the Santa Monica Bay Inn, Dennis checked into a different hospital in order to treat his wounds. Several hours later, he discharged himself and reportedly resumed drinking immediately.<ref name=Goldberg1984/><ref>{{cite news|title=Death of a Beach Boy|date=January 16, 1984|work=People Magazine|author=Jerome, Jim|author2=Buchalter, Gail|author3=Evans, Hilary|author4=Manna, Sal|author5=Pilcher, Joseph|author6=Rayl, Salley|name-list-style=amp|url=http://www.cinetropic.com/blacktop/people/|access-date=June 19, 2015|archive-date=April 12, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150412205705/http://www.cinetropic.com/blacktop/people/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

On December 28, Dennis [[drowned]] at [[Marina Del Rey, California|Marina Del Rey]] after drinking all day and then diving in the afternoon to recover his ex-wife's belongings, previously thrown overboard at the marina from his yacht three years earlier amidst their divorce.<ref name=Goldberg1984 /> Forensic pathologist [[Michael Hunter (forensic pathologist)|Michael Hunter]] believed that Dennis experienced [[shallow-water blackout]] just before his death.<ref>{{cite episode|series=[[Autopsy: The Last Hours of...]]|title=Dennis Wilson|network=[[Reelz]]|date=March 18, 2017|season=7|number=8|last1=Hunter|first1=Michael|last2=Taylor|first2=Ed|last3=Kelpie|first3=Michael}}</ref> On January 4, 1984, Dennis's body was [[buried at sea]] by the [[U.S. Coast Guard]], off the California coast. The Beach Boys released a statement shortly thereafter: "We know Dennis would have wanted to continue in the tradition of the Beach Boys. His spirit will remain in our music."<ref name=TheDay1984 /> His song "[[Farewell My Friend]]" was played at the funeral.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://people.com/archive/cover-story-death-of-a-beach-boy-vol-21-no-2/|title=Death of a Beach Boy|website=People|access-date=February 12, 2021|archive-date=May 15, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210515085821/https://people.com/archive/cover-story-death-of-a-beach-boy-vol-21-no-2/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

On December 28, Dennis [[drowned]] at [[Marina Del Rey, California|Marina Del Rey]] after drinking all day and then diving in the afternoon to recover his ex-wife's belongings, previously thrown overboard at the marina from his yacht three years earlier amidst their divorce.<ref name=Goldberg1984 /> Forensic pathologist [[Michael Hunter (forensic pathologist)|Michael Hunter]] believed that Dennis experienced [[shallow-water blackout]] just before his death.<ref>{{cite episode|series=[[Autopsy: The Last Hours of...]]|title=Dennis Wilson|network=[[Reelz]]|date=March 18, 2017|season=7|number=8|last1=Hunter|first1=Michael|last2=Taylor|first2=Ed|last3=Kelpie|first3=Michael}}</ref> On January 4, 1984, Dennis's body was [[buried at sea]] by the [[U.S. Coast Guard]], off the California coast. The Beach Boys released a statement shortly thereafter: "We know Dennis would have wanted to continue in the tradition of the Beach Boys. His spirit will remain in our music."<ref name=TheDay1984 /> His song "[[Farewell My Friend]]" was played at the funeral.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://people.com/archive/cover-story-death-of-a-beach-boy-vol-21-no-2/|title=Death of a Beach Boy|website=People|access-date=February 12, 2021|archive-date=May 15, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210515085821/https://people.com/archive/cover-story-death-of-a-beach-boy-vol-21-no-2/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 11:02, 28 April 2024

Dennis Wilson | |

|---|---|

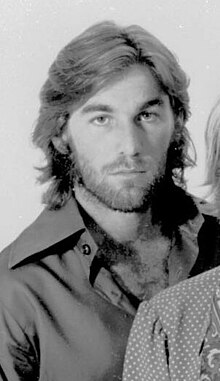

Wilson in 1968 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Dennis Carl Wilson |

| Born | December 4, 1944 Inglewood, California, U.S. |

| Origin | Hawthorne, California, U.S. |

| Died | December 28, 1983 (aged 39) Marina del Rey, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1961–1983 |

| Formerly of |

|

| Spouses | Carole E. Unrot

(m. 1965; div. 1968)Barbara Charren

(m. 1970; div. 1974)

(m. 1978; div. 1980)Shawn Marie Love (m. 1983) |

Dennis Carl Wilson (December 4, 1944 – December 28, 1983) was an American musician who co-founded the Beach Boys. He is best remembered as their drummer and as the middle brother of bandmates Brian and Carl Wilson. Dennis was the only true surfer in the Beach Boys, and his personal life exemplified the "California Myth" that the band's early songs often celebrated. He was also known for his association with the Manson Family and for co-starring in the 1971 film Two-Lane Blacktop.

Wilson served mainly on drums and baritone backing vocals for the Beach Boys. His playing can be heard on many of the group's hits, belying the popular misconception that he was always replaced on record by studio musicians.[1][2] He originally had few lead vocals on the band's songs due to his limited baritone range, but his prominence as a singer-songwriter increased following their 1968 album Friends. His music is characterized for reflecting his "edginess" and "little of his happy charm".[3] His original songs for the group included "Little Bird" (1968), "Forever" (1970) and "Cuddle Up" (1972). Friends and biographers have asserted that he was an uncredited writer on "You Are So Beautiful", a 1974 hit for Joe Cocker frequently performed by Wilson in concert.[4]

During his final years, Wilson struggled with alcoholism and the use of other drugs (including cocaine and heroin), exacerbating longstanding tensions with some of his bandmates. His solo album, Pacific Ocean Blue (1977), was released to warm reviews and moderate sales comparable to those of contemporaneous Beach Boys albums.[5] Sessions for a follow-up, Bambu, disintegrated before his death from drowning in 1983 at age 39. In 1988, he was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of the Beach Boys.

Childhood

Dennis Carl Wilson was born on December 4, 1944, the second child of Audree Neva (née Korthof) and Murry Gage Wilson.[6] He spent his family years with his brothers Brian and Carl and their parents in Hawthorne, California.[7] Dennis's role in the family dynamic, which he himself acknowledged, was that of the black sheep.[8] According to neighborhood friend David Marks, Dennis's "raucous behavior" inspired other kids to nickname him "Dennis the Menace".[9] Out of the three Wilson brothers, Dennis was the most likely to get beaten by their father[8] and suffer the worst treatment.[10] In 1976, he acknowledged, "We had a shitty childhood ... my dad was a tyrant. He used to wail on us, physically beat the crap out of us. I don't know kids who got it like we did."[11]

Possessed with an abundance of physical energy and a combative nature, Dennis often refused to participate in family singalongs, and likewise avoided vocalizing on the early recordings that Brian made on a portable tape recorder.[8] Dennis later described Brian as a "freak" who would "stay in his room all day listening to records rather than playing baseball. If you could get me to sing a song, yeah, I'd get into it. But I'd much rather play doctor with the girl next door or muck around with cars."[9] However, Dennis would sing with his brothers late at night in their shared bedroom, a song Brian later recalled as "our special one we'd sing", titled "Come Down, Come Down from the Ivory Tower". Brian said of the late night brotherly three-part harmonies: "We developed a little blend which aided us when we started to get into the Beach Boys stuff."[8]

Dennis noted of himself, "If my dad hadn't given me a BB gun when I was nine years old, my life would have been completely different. With that gun I had something I could take my anger out on. Hunting, fishing, racing have been my preoccupations ever since."[12] Brian told Melody Maker in 1966: "Dennis had to keep moving all the time. If you wanted him to sit still for one second, he's yelling and screaming and ranting and raving. He's the most messed-up person I know."[12] Around the time he was 14, Dennis began playing piano and learned to play boogie-woogie styles.[13] He remembered attending church gatherings with the rest of his family "because there was this outasight chick there ... [and] I used to try and play boogie woogie on the church piano on Friday nights when all the kids went there to play volleyball."[14]

Early career

Formation of the Beach Boys

The Wilsons' mother, Audree, forced Brian to include Dennis in the original lineup of the Beach Boys.[16][17] In 1960, Dennis began taking drum lessons at Hawthorne High School. Teacher Fred Morgan later said that Dennis had been "a beater, not a drummer" and "a fast learner when he wanted to learn."[18] According to Brian, "We kind of developed into a group sort of through the wishes of Dennis. He said that ... the kids at school knew I was musical because I had done some singing for assemblies and so on."[19] Recalling their first group rehearsals, Dennis said that he was initially "going to play bass, and then I decided to play drums. ... Drums seemed to be more exciting. I could always play bass if I wanted to."[20]

The Beach Boys officially formed in late 1961, with Murry taking over as manager, and had a local hit with their debut record "Surfin'", a song that Brian wrote at Dennis's urging.[21] Dennis recalled, "We got so excited ... I ran down the street screaming, 'Listen, we're on the radio!' It was really funky. That started it, the minute you're on the radio."[22] Though the Beach Boys developed their image based on the California surfing culture, Dennis was the only actual surfer in the band.[16] Carl supported, "Dennis was the only one who could really surf. We all tried, even Brian, but we were terrible. We just wanted to have a good time and play music."[20]

In early 1963, Dennis teamed with Brian's collaborator Gary Usher. Calling themselves the Four Speeds, they released the single "RPM" backed with "My Stingray".[23] In March 1964, Dennis moved out of the Wilson family home and took residence at an address in Hollywood.[24] In the sleeve notes of the band's July 1964 album All Summer Long, Dennis wrote: "They say I live a fast life. Maybe I just like a fast life. I wouldn't give it up for anything in the world. It won't last forever, either. But the memories will."[25] In December, Murry told a reporter that Dennis had been "a little too generous" with money and "cried when he learned about how much he had wasted. ... Where the other boys invested or saved their money, Dennis spent $94,000. He spent $25,000 on a home but the rest just went. Dennis [is] like that: he picks up the tab wherever he goes."[26]

In January 1965, Brian declared to his bandmates that he would no longer tour with the group for the foreseeable future. He later said that Dennis was so devastated by the news that his immediate reaction was to pick up "a big ashtray and told some people to get out of there or he'd hit them on the head with it. He kind of blew it."[27] Photographer Ed Roach, a close friend of Dennis's, stated that Brian was deterred from the stage due to jealousy over the adulation Dennis received from the audience.[28] Brian remembered that the attention Dennis received was "hard to handle". The girls would be going 'Dennis, Dennis' and run right past us to get to him."[23] Dennis later said of his brother, "Brian Wilson is the Beach Boys. He is the band. We're his fucking messengers. He is all of it. Period. We're nothing. He's everything."[29]

Increased record presence

Brian wrote that he had felt that Dennis "never really had a chance to sing very much", and so he gave him more leads on their March 1965 album The Beach Boys Today!.[30] Dennis sang "Do You Wanna Dance?" and "In the Back of My Mind". The former became the first song with a Dennis lead that was issued as an A-sided single, peaking at No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100.[31] Journalist Peter Doggett later said that Dennis' performance on the latter song "showed for the first time an awareness that his voice could be a blunt emotional instrument. ... his erratic croon cut straight to the heart, with an urgency that his more precise brothers could never have matched."[32] Released in July, Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) contained Dennis's favorite song by Brian, "Let Him Run Wild".[33]

By 1966, Dennis had begun using LSD.[34] His drumming contributions on Pet Sounds (1966) were limited to the track "That's Not Me".[35] Carl said, "Brian liked to use [session drummer] Hal [Blaine] because he was so much more reliable than Dennis, but whenever Dennis got the chance to play he always did a great job. He played drums on more of our records than most people realize. I think because he didn't play on Pet Sounds everybody assumes he never played at all, and that's just not the case."[36]

During the Smile sessions, Dennis played on "Vega-Tables", "Holidays", and "Good Vibrations".[37] It is rumored that the album's working title, Dumb Angel, referred to Dennis himself.[38] Van Dyke Parks, the project's lyricist, credited Wilson with inspiring the name of the would-be album track "Surf's Up".[39] Dennis said that the group ultimately scrapped Smile because they became "very paranoid about the possibility of losing our public. ... Drugs played a great role in our evolution but as a result we were frightened that people would no longer understand us, musically."[40]

In the latter part of the 1960s, Dennis started writing songs for the Beach Boys.[3] Dennis's collaborator Gregg Jakobson commented, "He started taking his piano playing more seriously. He'd ask Brian to show him stuff until he got a pretty good grasp of chords."[41] In January 1967, Dennis recorded the original composition "I Don't Know", but it was left unreleased. Music historian Keith Badman states that whether the piece was intended for Smile is not definitively known.[42] In December, Wilson recorded a piece called "Tune #1" that was intended for a solo project to be released on Brother Records, but it was also shelved.[43]

Wilson's first major released composition was "Little Bird", issued in April 1968 as the B-side of the "Friends" single.[44] "Little Bird" and another song, "Be Still", were co-written with poet Stephen Kalinich and featured on the album Friends (June 1968).[45] The group's next album, 20/20 (February 1969), marked the emergence of Dennis as a producer, including his original songs "Be with Me" and "All I Want to Do".[46] Dennis's "Celebrate the News" was released as the B-side to the standalone single "Break Away".[47]

By this time, the Beach Boys' popularity had faltered considerably. Dennis believed, "Because of the attitude of a few mental dinosaurs intent on exploiting our initial success, Brian's huge talent has never been fully appreciated in America and the potential of the group has been stifled. ... If the Beatles had suffered this kind of misrepresentation, they would have never got past singing 'Please, Please Me' and 'I Wanna Hold Your Hand' and leaping around in Beatle suits."[48]

In 2018, many of Wilson's unreleased tracks from this period were released for the compilations Wake the World: The Friends Sessions and I Can Hear Music: The 20/20 Sessions.[49]

Manson association

Contact with Manson

On April 6, 1968, Wilson was driving through Malibu when he noticed two female hitchhikers, Patricia Krenwinkel and Ella Jo Bailey. He picked them up and dropped them off at their destination.[50] On April 11, Wilson noticed the same two girls hitchhiking again. This time he took them to his home at 14400 Sunset Boulevard.[50][5] He recalled that he "told [the girls] about our involvement with the Maharishi and they told me they too had a guru, a guy named Charlie [Manson] who'd recently come out of jail after 12 years."[40] Wilson then went to a recording session; when he returned later that night, he was met in his driveway by Charles Manson, and when Wilson walked into his home, about a dozen people were occupying the premises, most of them young women. They were later known as members of the "Manson Family".[5] By Manson's own account, he had met Wilson on at least one prior occasion: at a friend's San Francisco house where Manson had gone to obtain marijuana. Manson claimed that Wilson invited him to visit his Sunset Boulevard home when Manson came to Los Angeles.[51]

Wilson was initially fascinated by Manson and his followers, referring to him as "the Wizard" in a Rave magazine article at the time.[52][53] The two struck a friendship, and over the next few months, members of the Manson Family – mostly women who were treated as servants – were housed in Wilson's residence, costing him approximately $100,000 (equivalent to $880,000 in 2023). Much of these expenses went on cars, clothes, food and penicillin injections for their persistent gonorrhoea.[5] This arrangement persisted for about six months.[54] In late 1968, Wilson told the magazine Record Mirror that "when I met [Charlie] I found he had great musical ideas. We're writing together now. He's dumb, in some ways, but I accept his approach and have [learned] from him."[40] He told reporters that he had been living with 17 women; when asked if he had been supporting them, Wilson replied, "No, if anything, they're supporting me. I had all the rich status symbols – Rolls-Royce, Ferrari, home after home. Then I woke up, gave away 50 to 60 percent of my money. Now I live in one small room, with one candle, and I'm happy, finding myself."[40]

Wilson introduced Manson to a few friends in the music business, including the Byrds' producer Terry Melcher.[53] Manson recorded numerous songs at Brian's home studio,[53] although the recordings remain unheard by the public.[55] Band engineer Stephen Desper said that the Manson sessions were done "for Dennis [Wilson] and Terry Melcher".[56] In September 1968, Wilson recorded a Manson song for the Beach Boys, originally titled "Cease to Exist" but reworked as "Never Learn Not to Love", as a single B-side released the following December. The writing was credited solely to Wilson.[57] When asked why Manson was not credited, Wilson explained that Manson relinquished his publishing rights in favor of "about a hundred thousand dollars' worth of stuff".[58][59] Around this time, the Family destroyed Wilson's Ferrari, as well as his Mercedes-Benz, which had been driven to a mountain outside Spahn Ranch.[60]

Disassociation

Growing fearful of the situation, Wilson distanced himself from Manson and moved out of the house, leaving Manson and his followers there, and subsequently took residence with Gregg Jakobson at a basement apartment in Santa Monica.[61] Virtually all of Wilson's household possessions were stolen by the Family; the members were evicted from his home three weeks before the lease was scheduled to expire.[61] When Manson subsequently sought further contact, he left a bullet with Wilson's housekeeper to be delivered with a threatening message.[5] Commenting on rumors that suggested Wilson had become afraid of Manson, Beach Boys collaborator Van Dyke Parks later said

One day, Charles Manson brought a bullet out and showed it to Dennis, who asked, "What's this?" And Manson replied, "It's a bullet. Every time you look at it, I want you to think how nice it is your kids are still safe." Well, Dennis grabbed Manson by the head and threw him to the ground and began pummeling him ... I heard about it, but I wasn't there. The point is, though, Dennis Wilson wasn't afraid of anybody![62]

Conversely, band manager Nick Grillo said that Wilson became more concerned after Manson had got "into a much heavier drug situation ... taking a tremendous amount of acid and Dennis wouldn't tolerate it and asked him to leave. It was difficult for Dennis because he was afraid of Charlie."[54] Writing in his 2016 memoir, Mike Love recalled Wilson saying he had witnessed Manson shooting a black man "in half" with an M16 rifle and hiding the body inside a well.[63] Melcher said that Wilson had been aware that the Family "were killing people" and had been "so freaked out he just didn't want to live anymore. He was afraid, and he thought he should have gone to the authorities, but he didn't, and the rest of it happened."[56]

Aftermath

In August 1969, Manson Family members perpetrated the Tate–LaBianca murders. Shortly afterward, Manson visited Wilson's home, telling him that he had "just been to the moon", and demanded money, which Wilson agreed to give to him.[64] That November, Manson was apprehended and charged with numerous counts of murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Wilson refused to testify against Manson.[53] He explained: "I couldn't. I was so scared."[65] Instead, he was privately interviewed by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi. Wilson's testimony was deemed inessential since Jakobson agreed to publicly testify and corroborate Wilson's claims.[66] Melcher later commented that Wilson had not been taken to the stand because the prosecutors "thought he was nuts, and by that time he was. He had a hard time separating reality from fantasy."[56] Bugliosi said that when he attempted to procure tapes of the songs that Wilson had recorded with Manson, Wilson responded that he had destroyed them because "the vibrations connected with them didn't belong on this earth."[67]

In the subsequent years, Wilson allegedly received death threats from members of the Manson Family, who telephoned his home and told him: "You're next".[65] In 1976, he commented that "I don't talk about Manson. I think he's a sick fuck. I think of Roman and all those wonderful people who had a beautiful family and they fucking had their tits cut off. I want to benefit from that?"[68] In the 1978 biography The Beach Boys and the California Myth, Wilson acknowledged the interest in his relationship with Manson and said: "I know why [he] did what he did. Someday, I'll tell the world. I'll write a book and explain why he did it."[65] According to biographer Mark Dillon: "Some attribute [Wilson's] subsequent spiral of self-destructive behavior ― particularly his drug intake ― to these fears and feelings of guilt for ever having introduced this evil Wizard into the Hollywood scene."[53]

Wilson's first wife Carole Freedman later told journalist Tom O'Neill that Wilson and other members of the Hollywood community had closer associations to Manson than what had been reported on the public record. O'Neill quoted Freedman saying that "It's a scary thing, and anyone who knows anything will never talk."[69] Upon Wilson's death, Manson was quoted as saying, "Dennis Wilson was killed by my shadow because he took my music and changed the words from my soul."[70] Manson never substantiated these claims.

Two-Lane Blacktop

From August 13 to late October 1970, Dennis shot his parts for the Universal Pictures road movie Two-Lane Blacktop.[71] The film depicts "The Driver" (James Taylor) and "The Mechanic" (Wilson) driving aimlessly across the United States in their 1955 Chevy, surviving on money earned from street racing.[72] It made its worldwide premiere on July 7, 1971, in New York City.[73] The film received mixed reviews but later gained stature as a "cult classic".[74]

Solo career

Unfinished album

Dennis continued writing songs for the Beach Boys' subsequent albums, including Sunflower (August 1970), which featured the single "Forever" – commonly regarded as one of his finest songs – and three others: "Slip On Through", "Got to Know the Woman", and "It's About Time".[75] Their inclusion was said to be at the insistence of Warner-Reprise, who felt that Dennis's songs sounded more contemporary than other rejected Beach Boys tracks.[3] "Slip On Through" became the first of Dennis's songs to be issued as an A-sided single by the Beach Boys.[76]

In the early 1970s, Wilson recorded material with Beach Boys touring musician Daryl Dragon to be set aside for a potential solo album, provisionally titled Freckles.[77] Dennis also offered Poops and Hubba Hubba as the album's working titles.[78][better source needed] On December 4, Stateside/EMI released "Sound of Free", a single issued only in Europe and the UK under the credit "Dennis Wilson & Rumbo".[79] The B-side was the Sunflower outtake "Lady" (also known as "Fallin' In Love").[80] At the Beach Boys' concerts in 1971, Dennis played solo piano renditions of his songs "Barbara" and "I've Got a Friend".[81][82] Biographer Jon Stebbins writes, "He was developing a power-ballad style that would become his signature."[82]

Dennis's two song contributions to the Beach Boys' August 1971 album Surf's Up – "4th of July" and "(Wouldn't It Be Nice to) Live Again" – were left off the record.[83] At the time, Dennis stated that he "pulled" the songs off the record because he did not feel they flowed well alongside the other tracks.[84] According to band manager Jack Rieley, the absence of any Dennis songs on Surf's Up was for two reasons: to quell political infighting within the group concerning the album's share of Wilson-brother songs, and because Dennis wanted to save his songs for a solo album.[85]

Engineer Stephen Desper said of Dennis's album, "ninety percent of it was ninety percent done".[82] Fred Vail, the band's co-manager, described the album as "diamonds never cut and polished", and explained, "The Beach Boys obviously weren't buying into his songs as part of the group output."[86] Several tracks from the album – "Baby Baby", "It's a New Day", "I've Got a Friend", "Behold the Night", "Hawaiian Dream", "Medley: All Of My Love / Ecology", and "Before" – were released on the 2021 box set Feel Flows.[87]

In June 1971, Dennis injured his hand badly enough to prevent him from playing drums for some time, so Ricky Fataar took over as the group's drummer between 1972 and 1974.[88] Stebbins writes, "Now, during concerts, the impulsive, physically aggressive Dennis would be reduced to sitting behind a keyboard or standing off to one side behind a microphone. It hurt him deeply. He felt like a caged animal. His drinking became worse and his participation in the band became erratic."[89] Biographer David Leaf wrote that, by this time, "Dennis was constantly quitting [the band] or getting fired and then rejoining."[90]

Two more songs intended for Dennis's album – "Make it Good" and "Old Movie" (retitled "Cuddle Up") – were ultimately placed on the Beach Boys' 1972 release Carl and the Passions – "So Tough".[91][92] Dennis wrote and produced two songs – "Steamboat" and "Only with You" – on their next album, Holland (1973).[93] A third song, "Carry Me Home", was left off the record.[94] The cover of their 1973 live album, The Beach Boys in Concert, depicts only Dennis onstage, although the album itself contains none of his songs.[95]

Pacific Ocean Blue

Wilson's onstage antics (including streaking) occasionally disrupted the Beach Boys' live shows.[96] He continued recording for his forthcoming solo album at the band's Brother Studios facility in Santa Monica.[97] In 1974, concurrent with the success of the greatest hits compilation Endless Summer, Dennis returned to his role behind the drums.[citation needed] According to Billy Hinsche, keyboardist for the Beach Boys' supporting band, it was during this year that Dennis co-wrote the lyrics and modified part of the melody of "You Are So Beautiful" while attending a party with Billy Preston.[98] Hinsche said, "I was there that night, and I would not dispute that Dennis had a hand in writing 'You Are So Beautiful,' and that's the reason we would do it in concert."[99]

By 1977, Dennis had amassed a stockpile of songs he had written and recorded while factions within the Beach Boys became too stressful for him. He expressed: "If these people want to take this beautiful, happy, spiritual music we've made and all the things we stand for and throw it out the window just because of money, then there's something wrong with the whole thing and I don't want any part of it."[5] He then approached James William Guercio, owner of Caribou Records, who stipulated "a structured recording process" before signing Dennis to a two-album contract.[5] According to Guercio: "My discussions with Dennis were along the lines of, 'You just tell Gregg [Jakobson] what you need - you have the studio and your job is to finish the dream. Finish the vision. Trish Roach [personal assistant] will do the paperwork and Gregg's the co-ordinator. It's your project... You've got to do what Brian used to do. Use anybody you want - it's your decision and you're responsible."[5]

Dennis released his debut solo album Pacific Ocean Blue in 1977. Although it sold moderately, ultimately reaching No. 96 on the US Billboard chart, its chart peak outperformed the following two Beach Boys albums. Dates were booked for a Dennis Wilson solo tour, but these were ultimately cancelled when his record company withdrew concert support.[101] He did occasionally perform his solo material on the 1977 Beach Boys tour.[102][better source needed] Despite Dennis claiming the album had "no substance",[100] Pacific Ocean Blue received positive reviews and later developed status as a cult item, ultimately selling nearly 250,000 copies.[3][103]

The album remained largely out of print between the 1990s and 2000s.[3] In June 2008, it was reissued on CD as an expanded edition. It was voted the 2008 "Reissue of the Year" in both Rolling Stone, and Mojo magazines and made No. 16 on the British LP charts and No. 8 on both the Billboard Catalog chart and the Billboard Internet Sales chart.[104]

Bambu

Pacific Ocean Blue's follow-up, Bambu, began production in 1978 at Brother Studios, with the collaboration of then Beach Boys keyboardist and Dennis' close friend Carli Muñoz as songwriter and producer. The first four songs officially recorded for Bambu were Muñoz's compositions: "It's Not Too Late", "Constant Companion", "All Alone", and "Under the Moonlight". The project was initially scuttled by lack of financing, Dennis' physical and mental decline due to alcoholism and severe drug abuse, which stemmed from his severe economic and marital problems at the time, and the distractions of simultaneous Beach Boys projects. Bambu was officially released in 2008 along with the Pacific Ocean Blue reissue.[citation needed] This material was also released on vinyl in 2017, without Pacific Ocean Blue, for Record Store Day.

Two songs from the Bambu sessions, "Love Surrounds Me" and "Baby Blue," were lifted for the Beach Boys' L.A. (Light Album) (1979).[105] Dennis and Brian also recorded together apart from the Beach Boys in the early 1980s. These sessions remain unreleased, although they are widely bootlegged as The Cocaine Sessions.[106][107]

Final years and death

In succeeding years, Dennis abused alcohol, cocaine and heroin.[108] By the last year of his life, he had virtually lost his normal speaking voice, struggled to sing, and had forgotten how to play drums, often missing Beach Boys performances in the process.[109] Following a confrontation on an airport tarmac, he declared to Rolling Stone on September 3, 1977, that he had left the Beach Boys: "They kept telling me I had my solo album now, like I should go off in a corner and leave the Beach Boys to them. The album really bothers them. They don't like to admit it's doing so well; they never even acknowledge it in interviews."[110] Two weeks later, disputes were resolved, and Dennis rejoined the group.[110]

In January 1981, Brian's then-girlfriend and nurse Carolyn Williams accused Dennis of enticing Brian to purchase about $15,000 worth of cocaine. When Brian's bodyguard Rocky Pamplin and the Wilsons' cousin Stan Love learned of this incident, they physically assaulted Dennis at his home. For the assault, they were fined about $1,000, and Dennis filed a restraining order.[111]

As the Beach Boys pressured Brian to readmit himself into Eugene Landy's 24-hour therapy program, Dennis was informed by friends that he would be the band's next target, to Dennis's disbelief.[108] His disbelief was proven wrong as the rest of the band gave him an ultimatum after his last performance in September 1983 to check into rehab for his alcohol problems or be banned from performing live with them.[108] By then, he was homeless and living a nomadic life.[108] He checked into a therapy center in Arizona for two days, and then on December 23, 1983, checked into St. John's Hospital in Santa Monica, where he stayed until the evening of December 25. Following a violent altercation at the Santa Monica Bay Inn, Dennis checked into a different hospital in order to treat his wounds. Several hours later, he discharged himself and reportedly resumed drinking immediately.[108][112]

On December 28, Dennis drowned at Marina Del Rey after drinking all day and then diving in the afternoon to recover his ex-wife's belongings, previously thrown overboard at the marina from his yacht three years earlier amidst their divorce.[108] Forensic pathologist Michael Hunter believed that Dennis experienced shallow-water blackout just before his death.[113] On January 4, 1984, Dennis's body was buried at sea by the U.S. Coast Guard, off the California coast. The Beach Boys released a statement shortly thereafter: "We know Dennis would have wanted to continue in the tradition of the Beach Boys. His spirit will remain in our music."[114] His song "Farewell My Friend" was played at the funeral.[115]

Dennis's widow Shawn Love reported that Dennis had wanted a burial at sea, and his brothers Carl and Brian did not want Dennis cremated.[114] At the time, only veterans of the Coast Guard and Navy were allowed to be buried in US waters without being first cremated, but Dennis's burial was made possible by the intervention of then-President Ronald Reagan.[116] In 2002, Brian expressed unhappiness with the arrangement, believing that Dennis should have been given a traditional burial.[117]

Artistry and legacy

[His] intense, melancholic and soulful [songs] would usually sit at odds with the group's more wholesome image. ... As the Beach Boys descended into a parody of their former selves it would be Dennis who would twist their trademark sounds into new shapes. At his best this would sound something like Kurt Cobain produced by Phil Spector.

PopMatters writer Tony Sclafani summarized in 2007:

By all appearances the happy-go-lucky Beach Boy, Dennis Wilson lived out the proverbial live-fast-die-young motto. To some degree, that's a fair assessment. Dennis did indeed drive fast cars, hang with hippies (including Charles Manson) and dated his share of beautiful California women. But like his older brother Brian, Dennis was bullied mercilessly by his father. His wild side masked an underside that was, by turns, brooding, self-loathing, sensitive, and anxious. Dennis's music reflected his edginess and exhibited little of his happy charm, setting it apart from Brian's music. Dennis never sang about fun, and no images of surfboards or surfer girls ever appear in a Dennis Wilson song.[3]

A common misconception is that Dennis' drumming in the Beach Boys' recordings was filled in exclusively by studio musicians.[2] His drumming is documented on a number of the group's early hits, including "I Get Around", "Fun, Fun, Fun", and "Don't Worry Baby".[118] As the mid-1960s approached, Brian often hired session drummers, such as Hal Blaine, to perform on studio recordings due to Dennis' limited drumming technique and frequent unavailability. Dennis accepted this situation with equanimity.[119][120]

In 1967, Dennis was cited as "the closest to brother Brian's own musical ideals ... He always emphasises the fusion, in their work, of pop and classical music."[121] Dennis said his brother Brian was an "inspiration", not an influence, and that "Musically, I'm far apart from Brian. He's a hundred times more than what I am musically."[100]

In 1988, Dennis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame posthumously as a member of the Beach Boys.[122]

Personal life

Wilson's first wife was Carole Freedman, with whom he had a daughter, Jennifer, and adopted son, Scott, from her previous relationship. They married on July 29, 1965, and divorced in 1967.[123] His second was Barbara Charren, with whom he had two sons, Michael and Carl.[72] Dennis's songs "Lady" and "Barbara" were written about Charren.[124] Dennis was then married twice to actress Karen Lamm, the former wife of Chicago keyboardist Robert Lamm, in 1976 and again in 1978.[108]

In 1978, following a Beach Boys concert in Arizona, Dennis was arrested for sharing drugs and alcohol with a 16-year-old girl in his hotel room. Dennis referred to the incident as a setup, and paid $100,000 in legal fees.[125]

From 1979 to 1982, Dennis had a relationship with Christine McVie of Fleetwood Mac.[108][126] Fleetwood Mac's 1982 song "Only Over You" was written by McVie about Dennis.[127] McVie later said of Dennis, "Half of him was like a little boy, and the other half was insane."[128] Mick Fleetwood, who had introduced the couple to each other, wrote that "Chris almost went mad trying to keep up with Dennis, who was already like a man with twenty thyroid glands, not counting the gargantuan amounts of coke and booze he was shoving into himself."[127]

At the time of his death, Wilson was married to (but separated from) Shawn Marie Harris (born on December 30, 1964),[citation needed] who claimed to be the daughter of his first cousin and bandmate, Mike Love,[128] although Love disputed the claim.[108] Wilson and Shawn had one son, Gage Dennis, born September 3, 1982.[129]

Gregg Jakobson speculated that Wilson may have had undiagnosed ADHD.[130] According to biographer Steven Gaines, Dennis had told friends that he had been raped by "a black man", although the details Dennis gave were inconsistent, having variously disputing the year of the incident, while in jail, in an alley, or on his Harmony boat. Gaines wrote, "Obviously, this was a recurring fantasy, and whether or not any of these stories is true remains unknown."[131]

Fictional depictions

- In the 1990 television movie Summer Dreams: The Story of the Beach Boys, Wilson is portrayed by Bruce Greenwood.[132]

- In the 2000 miniseries The Beach Boys: An American Family, Wilson is portrayed by Nick Stabile.

- In the 2015 movie Love & Mercy, Wilson is portrayed by Kenny Wormald.

- In 2019, Wilson appeared as a character on the NBC crime drama series Aquarius, portrayed by Andy Favreau.[133]

- Wilson is a minor character in Quentin Tarantino's 2021 novel Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Discography

Albums

| Year | Album details | Chart positions | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US (1977) |

UK (2008) |

NOR (2008) | |||||||||||

| 1977 | Pacific Ocean Blue

|

96 | 16 | 5 | |||||||||

| 2017 | Bambu (The Caribou Sessions)

|

— | — | — | |||||||||

Singles

| Date | Title | Label |

|---|---|---|

| December 1970 | "Sound of Free" / "Lady" | Stateside |

| September 1977 | "River Song" / "Farewell My Friend" | Caribou |

| October 1977 | "You and I" / "Friday Night" |

Songs (written or co-written by Dennis Wilson)

- Surfer Girl (1963)

- Shut Down Volume 2 (1964)

- "Denny's Drums"

- Friends (1968)

- "Friends"

- "Be Here in the Mornin'"

- "When a Man Needs a Woman"

- "Little Bird"

- "Be Still"

- 20/20 (1969)

- "Be with Me"

- "All I Want to Do"

- "Never Learn Not to Love"

- Sunflower (1970)

- "Slip On Through"

- "Got to Know the Woman"

- "It's About Time"

- "Forever"

- Carl and the Passions – "So Tough" (1972)

- "Make It Good"

- "Cuddle Up"

- Holland (1973)

- "Steamboat"

- "Only with You"

- Pacific Ocean Blue (1977)

- "River Song"

- "What's Wrong"

- "Moonshine"

- "Friday Night"

- "Dreamer"

- "Thoughts of You"

- "Time"

- "You and I"

- "Pacific Ocean Blues"

- "Farewell My Friend"

- "Rainbows"

- "End of the Show"

- Pacific Ocean Blue CD reissue bonus tracks

- "Tug of Love"

- "Holy Man"

- "Mexico"

- Bambu (The Caribou Sessions) (2017)

- "School Girl"

- "Love Remember Me'

- "Wild Situation"

- "Common"

- "Are You Real"

- "He's a Bum"

- "Cocktails"

- "I Love You"

- "Time for Bed"

- "Album Tag Song"

- "Piano Variations on "Thoughts of You""

- L.A. (Light Album) (1979)

- "Love Surrounds Me"

- "Baby Blue"

- Ten Years of Harmony (1981)

- Good Vibrations: Thirty Years of The Beach Boys (1993)

- Endless Harmony Soundtrack (1997)

- "Barbara"

- Ultimate Christmas (1998)

- "Morning Christmas"

- The Smile Sessions (2011)

- "I Don't Know"

- Made in California (2013)

- "(Wouldn't It Be Nice to) Live Again"

- "Barnyard Blues"

- "My Love Lives On"

- "Celebrate the News"

- "Sound of Free"

- "Lady"

- Wake the World: The Friends Sessions (2018)

- "Away"

- "Untitled 1/25/68"

- I Can Hear Music: The 20/20 Sessions (2018)

- "Well, You Know I Knew"

- "Love Affair"

- "Peaches"

- "The Gong"

- "A Time to Live in Dreams" (Also on Hawthorne, CA (2003))

- "Mona Kana" (Also on Made in California (2013))

- 1969: I'm Going Your Way (2019)

- "I'm Going Your Way"

- Feel Flows (album) (2021)

- "Baby Baby"

- "It's a New Day"

- "Medley: All Of My Love/Ecology"

- "Before"

- "Behold the Night"

- "Hawaiian Dream"

- "I've Got A Friend"

- Sail On Sailor – 1972 (2022)

- "Carry Me Home"

- 1972 Release (2022)

- "Unknown Piano/Synth Track"

References

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Orme, Mike (July 8, 2008). "Pacific Ocean Blue: Legacy Edition". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Sclafani, Tony (November 1, 2007). "Dennis Wilson's Majestic Solo Work". PopMatters. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ "Wilson's talent sings forth on 'Pacific' re-release". Chicago Tribune. July 20, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Webb, Adam (December 14, 2003). "A profile of Dennis Wilson: the lonely one". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 14.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Leaf 1978, pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 47.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 15.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 18.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 11.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 75–77.

- ^ a b Leaf 1978, p. 19.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 27.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 17.

- ^ a b Stebbins 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 52.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 17, 40.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 45.

- ^ Wilson & Greenman 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Dillon 2012, p. 47.

- ^ Doggett 1997, p. 164.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 76.

- ^ Love 2016, p. 132.

- ^ Slowinski, Craig. "Pet Sounds LP". beachboysarchives.com. Endless Summer Quarterly. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 23.

- ^ The Smile Sessions (deluxe box set booklet). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records. 2011.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 156.

- ^ a b c d Griffiths, David (December 21, 1968). "Dennis Wilson: "I Live With 17 Girls"". Record Mirror. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 92.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 173.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 207.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 27, 58, 92.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 222.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 240.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 99.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 101.

- ^ "Happy New Music Friday! 'Wake the World: The Friends Sessions' Is Out Now!". thebeachboys.com. December 7, 2018. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 216.

- ^ Emmons, Nuel (1988). Manson in His Own Words. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3024-0.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d e Dillon, Mark (June 13, 2012). "Mark Dillon: Dennis Wilson and Charles Manson". National Post. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Doe, Andrew Grayham. "Unreleased Albums". Bellagio 10452. Endless Summer Quarterly. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c O'Neill 2019.

- ^ Barlass, Tyler (July 16, 2008). "Song Stories - "Never Learn Not To Love" (1968)". Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 137.

- ^ Nolan, Tom (November 11, 1971). "Beach Boys: A California Saga, Part II". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 223–224.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Holdship, Bill (April 6, 2000). "Heroes and Villains". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Bitette, Nicole (August 31, 2016). "Beach Boy Mike Love alleges bandmate watched Charles Manson carry out murder". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 216.

- ^ a b c Leaf 1978, p. 136.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 137.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 223.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 219.

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 100.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 274, 277.

- ^ a b Stebbins 2000, p. 104.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 297.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 110.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 102.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 108–109, 150.

- ^ Doe, Andrew G. "GIGS71". Bellagio 10452. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 279.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 262, 279.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Stebbins 2000, p. 112.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Ruddock, Martin; Gater, Russ (September 2021). "Wouldn't It Be Nice To Live Again – The Dennis Wilson & Rumbo LP 'Poops'". Shindig Magazine. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 279, 283, 298.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (June 3, 2021). "The Beach Boys' New 'Feel Flows' Box Set: An Exclusive Guide". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 296.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 146.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 283, 307.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 120.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 143.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 121.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 122.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 127.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 153.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b c Leaf, David (September 1977). "Dennis Wilson Interview". Pet Sounds. 1 (3). Archived from the original on November 1, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 172–173.

- ^ "Dennis Wilson solo recordings". Local Gentry. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ "The Making Of Dennis Wilson's PacificOcean Blue". Recordcollectormag.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Wilson's 'Ocean' Set For Expanded Reissue". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 182.

- ^ Doe, Andrew Grayham. "GIGS82". Endless Summer Quarterly. Archived from the original on December 15, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ Stebbins 2011, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Goldberg, Michael (June 7, 1984). "Dennis Wilson: The Beach Boy Who Went Overboard". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ O'Casey, Matt (February 26, 2010). "Dennis Wilson: The Real Beach Boy". Legends.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Swenson, John (October 20, 1977). "The Beach Boys - No More Fun Fun Fun". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ Gaines, Steven (October 21, 1986). "Beach Boy drummer 'goes for it' and ends up beat up". The Spokesman-Review Spokane Chronicle.

- ^ Jerome, Jim; Buchalter, Gail; Evans, Hilary; Manna, Sal; Pilcher, Joseph & Rayl, Salley (January 16, 1984). "Death of a Beach Boy". People Magazine. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Hunter, Michael; Taylor, Ed; Kelpie, Michael (March 18, 2017). "Dennis Wilson". Autopsy: The Last Hours of... Season 7. Episode 8. Reelz.

- ^ a b "Beach Boys drummer buried in rites at sea". The Day. January 5, 1984. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ "Death of a Beach Boy". People. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Reagan Helps Get Approval For Musician's Burial at Sea". The New York Times. UPI. January 3, 1984. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ Ginny, Dougary (May 31, 2002). "After the wipeout". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Boyd, Alan; Linette, Mark; Slowinski, Craig (2014). Keep an Eye on Summer 1964 (Digital Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records. Archived from the original on April 30, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2007. (Mirror Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Doe & Tobler 2004, pp. V, 9.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Grant, Mike (October 11, 2011). "'Our influences are of a religious nature': the Beach Boys on Smile". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 231.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 109.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 169.

- ^ "Christine McVie Keeps a Level Head After Two Decades In the Fast Lane". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Stebbins 2000, p. 213.

- ^ a b Stebbins 2000, p. 214.

- ^ Agu, Ngozika (July 18, 2023). "Whatever Happened To Shawn Marie Love, Dennis Wilson's Wife?". Byliner. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Dillon 2012, p. 174.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 260.

- ^ Stebbins 2000, p. 232.

- ^ "April Grace Spies Role In 'Berlin Station'; Andy Favreau Grooves With 'Aquarius'". November 19, 2015. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

Bibliography

- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6.

- Dillon, Mark (2012). Fifty Sides of the Beach Boys: The Songs That Tell Their Story. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-77090-198-8.

- Doe, Andrew; Tobler, John (2004). The Complete Guide to the Music of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-426-2. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- Doggett, Peter (1997). "Holy Man and Slow Booze: Dennis Wilson". In Abbott, Kingsley (ed.). Back to the Beach: A Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys Reader. Helter Skelter. ISBN 978-1-90092-402-3.

- Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: The True Story of The Beach Boys. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806479.

- Leaf, David (1978). The Beach Boys and the California Myth. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 978-0-448-14626-3.

- Love, Mike (2016). Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-698-40886-9. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- O'Neill, Tom (2019). Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-47757-4. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- Stebbins, Jon (2000). Dennis Wilson: The Real Beach Boy. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-404-7.

- Stebbins, Jon (2011). The Beach Boys FAQ: All That's Left to Know About America's Band. Backbeat Books. ISBN 9781458429148. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- Wilson, Brian; Greenman, Ben (2016). I Am Brian Wilson: A Memoir. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82307-7. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

Further reading

- Sharp, Ken (2017). Dreamer: The Making of Dennis Wilson's Pacific Ocean Blue.

- Webb, Adam (2001). Dumb Angel: The Life and Music of Dennis Wilson. Creation Books. ISBN 978-1-84068-051-5.

External links

- Dennis Wilson at IMDb

- Pacific Ocean coup: how Ronald Reagan helped bury a Beach Boy at sea

- Cease to Exist: The Saga of Dennis Wilson and Charles Manson – compendium of first-hand accounts edited by Jason Austin Penick

- Dennis Wilson

- 1944 births

- 1983 deaths

- 20th-century American drummers

- Accidental deaths in California

- Alcohol-related deaths in California

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American people of Swedish descent

- American male drummers

- American rock drummers

- American surfers

- The Beach Boys members

- Burials at sea

- Brian Wilson

- Carl Wilson

- Deaths by drowning in California

- Musicians from Hawthorne, California

- Musicians from Inglewood, California

- Record producers from California

- 20th-century American male musicians

- Stateside Records artists