BOOMERanG experiment: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Properly linked MAT/TOCO to its proper page |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

==Results== |

==Results== |

||

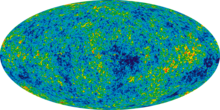

[[Image:Boomerang CMB.jpeg|thumb|200px|right|CMB Anisotropy measured by BOOMERanG]] |

[[Image:Boomerang CMB.jpeg|thumb|200px|right|CMB Anisotropy measured by BOOMERanG]] |

||

Together with experiments like the [[Saskatoon experiment]], TOCO, MAXIMA, and others, the BOOMERanG data from 1997 and 1998 determined the angular diameter distance to the surface of last scattering with high precision. When combined with complementary data regarding the value of [[Hubble's law|Hubble's constant]], the Boomerang data determined the [[Friedmann equations|geometry of the Universe]] to be flat,<ref name="Nature_27Apr00"/> supporting the [[supernova]] evidence for the existence of [[dark energy]]. The 2003 flight of Boomerang resulted in extremely high [[signal-to-noise ratio]] maps of the CMB temperature anisotropy, and a measurement of the polarization of the [[Cosmic microwave background|CMB]].<ref name="MacTavish">{{cite journal|title=Cosmological Parameters from the 2003 Flight of BOOMERANG|date=August 2006|journal=[[Astrophysical Journal]]|volume=647|pages=799–812|last1=MacTavish|first1=C. J.|issue=2|display-authors=etal|doi=10.1086/505558|arxiv=astro-ph/0507503|bibcode=2006ApJ...647..799M|s2cid=18690323}}</ref> |

Together with experiments like the [[Saskatoon experiment]], [[Mobile Anisotropy Telescope|MAT/TOCO]], MAXIMA, and others, the BOOMERanG data from 1997 and 1998 determined the angular diameter distance to the surface of last scattering with high precision. When combined with complementary data regarding the value of [[Hubble's law|Hubble's constant]], the Boomerang data determined the [[Friedmann equations|geometry of the Universe]] to be flat,<ref name="Nature_27Apr00"/> supporting the [[supernova]] evidence for the existence of [[dark energy]]. The 2003 flight of Boomerang resulted in extremely high [[signal-to-noise ratio]] maps of the CMB temperature anisotropy, and a measurement of the polarization of the [[Cosmic microwave background|CMB]].<ref name="MacTavish">{{cite journal|title=Cosmological Parameters from the 2003 Flight of BOOMERANG|date=August 2006|journal=[[Astrophysical Journal]]|volume=647|pages=799–812|last1=MacTavish|first1=C. J.|issue=2|display-authors=etal|doi=10.1086/505558|arxiv=astro-ph/0507503|bibcode=2006ApJ...647..799M|s2cid=18690323}}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Latest revision as of 03:05, 1 May 2024

The telescope being readied for launch | |

| Alternative names | Balloon Observations Of Millimetric Extragalactic Radiation and Geophysics |

|---|---|

| Location(s) | Antarctica |

| Telescope style | balloon-borne telescope cosmic microwave background experiment radio telescope |

| Website | cmb |

| | |

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

BOOMERanG experiment (Balloon Observations Of Millimetric Extragalactic Radiation And Geophysics) was an experiment that flew a telescope on a (high-altitude) balloon and measured the cosmic microwave background radiation of a part of the sky during three sub-orbital flights. It was the first experiment to make large, high-fidelity images of the CMB temperature anisotropies, and is best known for the discovery in 2000 that the geometry of the universe is close to flat,[1] with similar results from the competing MAXIMA experiment.

By using a telescope which flew at over 42,000 meters high, it was possible to reduce the atmospheric absorption of microwaves to a minimum. This allowed massive cost reduction compared to a satellite probe, though only a tiny part of the sky could be scanned.

The first was a test flight over North America in 1997. In the two subsequent flights in 1998 and 2003 the balloon was launched from McMurdo Station in the Antarctic. It was carried by the Polar vortex winds in a circle around the South Pole, returning after two weeks. From this phenomenon the telescope took its name.

The BOOMERanG team was led by Andrew E. Lange of Caltech and Paolo de Bernardis of the University of Rome La Sapienza.[2]

Instrumentation

[edit]The experiment uses bolometers[3] for radiation detection. These bolometers are kept at a temperature of 0.27 kelvin. At this temperature the material has a very low heat capacity according to the Debye law, thus incoming microwave light will cause a large temperature change, proportional to the intensity of the incoming waves, which is measured with sensitive thermometers.

An off-axis 1.3-meter primary mirror[3] focuses the microwaves onto the focal plane, which consist of 16 horns. These horns, operating at 145 GHz, 245 GHz and 345 GHz, are arranged into 8 pixels. Only a tiny fraction of the sky can be seen concurrently, so the telescope must rotate to scan the whole field of view.

Results

[edit]

Together with experiments like the Saskatoon experiment, MAT/TOCO, MAXIMA, and others, the BOOMERanG data from 1997 and 1998 determined the angular diameter distance to the surface of last scattering with high precision. When combined with complementary data regarding the value of Hubble's constant, the Boomerang data determined the geometry of the Universe to be flat,[1] supporting the supernova evidence for the existence of dark energy. The 2003 flight of Boomerang resulted in extremely high signal-to-noise ratio maps of the CMB temperature anisotropy, and a measurement of the polarization of the CMB.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b de Bernardis, P.; et al. (27 April 2000). "A Flat Universe from High-Resolution Maps of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation". Nature. 404 (6781): 955–959. arXiv:astro-ph/0004404. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..955D. doi:10.1038/35010035. PMID 10801117. S2CID 4412370.

- ^ Glanz, James (27 April 2000). "Clearest Picture of Infant Universe Sees It All and Questions It, Too". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ a b Crill, B. P.; et al. (October 2003). "BOOMERANG: A Balloon-borne Millimeter Wave Telescope and Total Power Receiver for Mapping Anisotropy in the Cosmic Microwave Background". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 148 (2): 527–541. arXiv:astro-ph/0206254. Bibcode:2003ApJS..148..527C. doi:10.1086/376894. S2CID 545283.

- ^ MacTavish, C. J.; et al. (August 2006). "Cosmological Parameters from the 2003 Flight of BOOMERANG". Astrophysical Journal. 647 (2): 799–812. arXiv:astro-ph/0507503. Bibcode:2006ApJ...647..799M. doi:10.1086/505558. S2CID 18690323.