Siege of Goražde: Difference between revisions

نوفاك اتشمان (talk | contribs) added Category:Yugoslav People's Army using HotCat |

|||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

According to the [[Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo]] (RDC), Goražde recorded 511 civilians (126 Serbs and 385 non-Serbs, mostly [[Bosniaks]]) and 1,100 soldiers who lost their lives during the war.<ref>{{cite web|publisher=Prometej.ba|author=Ivan Tučić|title=Pojedinačan popis broja ratnih žrtava u svim općinama BiH|url=http://www.prometej.ba/clanak/drustvo-i-znanost/pojedinacan-popis-broja-ratnih-zrtava-u-svim-opcinama-bih-997|date=February 2013|access-date=4 August 2014}}</ref> Some sources place the total number of people killed or wounded at roughly 7,000, 548 of whom were children.<ref name=":0" /> |

According to the [[Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo]] (RDC), Goražde recorded 511 civilians (126 Serbs and 385 non-Serbs, mostly [[Bosniaks]]) and 1,100 soldiers who lost their lives during the war.<ref>{{cite web|publisher=Prometej.ba|author=Ivan Tučić|title=Pojedinačan popis broja ratnih žrtava u svim općinama BiH|url=http://www.prometej.ba/clanak/drustvo-i-znanost/pojedinacan-popis-broja-ratnih-zrtava-u-svim-opcinama-bih-997|date=February 2013|access-date=4 August 2014}}</ref> Some sources place the total number of people killed or wounded at roughly 7,000, 548 of whom were children.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

== |

== See also == |

||

* [[Siege of Sarajevo]] |

|||

* [[Siege of Goražde]] |

|||

* [[Siege of Srebrenica]] |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

Revision as of 19:20, 31 May 2024

| Siege of Goražde | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bosnian War | |||||||

A memorial dedicated to the victims of the siege in Goražde | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(1992–95) |

(1992–95) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

File:Logo of the Yugoslav People's Army (1991–1992).svg Yugoslav People's Army (1992) |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 511 civilians | |||||||

The siege of Goražde (Template:Lang-bs; Template:Lang-bs) refers to engagements during the Bosnian War (1992–95) in and around the town of Goražde in eastern Bosnia.

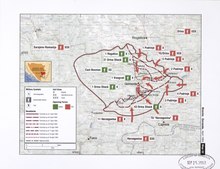

On 4 May 1992, Goražde was besieged by the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS).[1] It was attacked from three sides - from the north, the south and the east. The Muslim majority towns in close proximity to Goražde, such as Foča, Rogatica and Višegrad had already been taken by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) in the earlier months of 1992, leaving only the Muslim stronghold of Goražde in the southern Bosnian Podrinje region. After the Dayton Agreement was signed to end the war,[2][3] the enclave was connected to the rest of Bosnia.

Background

Goražde is a small town in eastern Bosnia close to the Serbian border. According to the 1991 Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia census, Goražde (including the present-day Novo Goražde) had a population of 37,573,[4] 26,296 of which were Bosniaks and 9,843 Serbs. The town of Goražde itself was inhabited by 16,273 people[5] when Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia in 1992.

The Serbs established the RAM Plan, developed by the State Security Administration (SDB) and a group of selected Serb officers of the JNA with the purpose of organizing Serbs outside Serbia, consolidating control of the fledgling SDP, and the prepositioning of arms and ammunition.[6] Alarmed, the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia on 15 October 1991, shortly followed by the establishment of the Serbian National Assembly by the Bosnian Serbs.[7]

In January of 1992, Bosnian Serb state was declared, ahead of the 29 February–1 March referendum on independence.[8] Later renamed the Republika Srpska,[9] it developed its own military as the JNA withdrew from Croatia and handed over its weapons, equipment and 55,000 troops to the newly created Bosnian Serb army.[8] By 1 March, Bosnian Serb forces set up barricades in Sarajevo and elsewhere and later that month Bosnian Serb artillery began shelling the town of Bosanski Brod.[10] By 4 April, Sarajevo was shelled.[9] In May 1992, the ground forces of Bosnian Serb state officially became known as the Army of Republika Srpska.[11] By the end of 1992, the VRS held seventy percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[12]

At the outbreak of the war, eastern Bosnia, a Bosniak-majority territory before the war,[5] was subjected to ethnic cleansing operations and numerous atrocities involving murder, rape on a massive scale, plundering, and forced relocation by Serb forces and paramilitary gangs.[13][14] Taking place throughout the municipalities of Srebrenica, Vlasenica, Rogatica, Bratunac, Višegrad, Zvornik and Foča,[15] the purpose of these operations was to create in eastern Bosnia a contiguous Serb-controlled land having a common border with Serbia.[16]

Siege

The VRS had begun a campaign of indiscriminate shelling, often hitting civilian buildings and inflicting mass casualties. Sniper attacks were frequent and many civilians chose not to leave their homes. The fighting was reported to become even more intense on weekends, with Serbs from Serbia proper joining in to fight the Bosniaks.[17] In response to the inhumane treatment of civilians by the VRS, the local units of the Bosnian Ministry of the Interior (MUP) began a campaign of retribution against the Bosnian Serb civilians who were still living in the city. Dozens of local Serbs were arrested and executed in the local school; a hundred more, including women and children, were forcibly held as human shields to protect the police station from shelling.[18][19]

In August 1992, 1st and 31st Drina Strike Brigades of the ARBiH successfully accomplished the Operation Circle, thereby pushing the VRS forces out of the eastern suburbs.[20] However, the siege continued. As the war progressed, Goražde's humanitarian situation began to worsen. The massive influx of refugees from the surrounding areas meant that Goražde's population had increased from the pre-war number of 37,573,[4] to roughly 70,000. This sharp increase was because non-Serbs, mainly Bosniaks, had fled their homes from the surrounding areas such as Višegrad, Foča, and Rogatica. Disease was extremely prevalent in Goražde.[17]

In April 1993, Goražde was made into a United Nations Safe Area, along with other besieged towns such as Srebrenica, Tuzla and Bihać.[21] The United Nations provided humanitarian assistance for the starving civilians trapped in Goražde enclave. They established safe passes which would transport aid to the enclave but eventually closed the routes for the humanitarian convoys and instead dropped aid packages by air due to large casualties using the safe passes. These packages contained little food, and were insufficient for the whole population.[17]

In May 1993, the Bosnian Serbs launched an offensive in the Goražde region. The VRS secured complete control of the Višegrad municipality, pushing the Bosniaks out of the western countryside of the town, and took the villages of Međeđa, Kaoštice and Ustiprača using the 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th Podrinje Brigades. The Serbs then used the 11th and 18th Herzegovina Brigades, the 1st Guards Motorised Brigade, and the 65th Protection Motorised Regiment to seize the town of Trnovo on 11 July 1993 and take the nearby village of Jabuka, finally severing the land bridge that connected Goražde to central Bosnia. The offensive also encircled Sarajevo using the 1st Igman Infantry Brigade, the 2nd Sarajevo Infantry Brigade and the Elms Motorized Regiment.[22] Though, this encirclement was broken later.

Between 30 March and 23 April 1994, the Serbs launched another major offensive with the aim overrunning Goražde. On 9 April 1994, the Secretary General of the UN, citing Security Resolution 836, threatened airstrikes on the Serbian forces which were attacking the Goražde enclave. For the next two days, NATO planes carried out air strikes against Serb tanks and outposts, however, these attacks did little to stop the overwhelming Bosnian Serb Army. Knowing Goražde would fall without foreign intervention, NATO issued the Serbs an ultimatum, and the Serbs were forced to comply. Under the conditions of the ultimatum, the Serbs had to withdraw all militias to 3km from the town by 23 April 1994, and all of their artillery and armored vehicles 20 km (12 mi) from the town by 26 April 1994. The VRS complied.[23]

On 28 May 1995 Goražde was again targeted by the Bosnian Serbs, who launched an assault on UNPROFOR guard posts east and north of the settlement, overwhelming and capturing at gunpoint 33 British UN servicemen from the Royal Welch Fusiliers manning four observation posts and two checkpoints[24][25] on the west bank of the Drina. The remaining troops, who were stationed at three outposts[24] on the east bank, managed to slip away and helped Bosniak reinforcements to prevent Bosnian Serbs from taking a key hill overlooking the town. This action is credited with saving the town from suffering the same fate of Srebrenica, where the Bosnian Serbs continued the siege after the failed attempt.[26] After learning of the Serb attack, British commander Lieutenant General Rupert Smith ordered all the UNPROFOR forces still deployed around Goražde to return to their base.[24][25]

Role of the UN

"I would say that the role of the international community in general in Bosnia and Herzegovina was very dishonourable"

— Ferid Buljubašić[27]

In April 1994, during the large-scale Serb offensive on Goražde, a group of 20 soldiers from the UK’s Special Air Service regiment had been hurriedly evacuated under the perception that the enclave would fall into Serb hands. This immediately ruined the reputation of the UN as they were seen that they would rather leave than defend the town's doomed population of 70,000.[17][27] NATO planes also bombed Serb tanks which had already been destroyed.[27] The British UN detachment in Goražde had also been reported to be faking execution of their tasks and generally being 'extremely inclined towards the Serbs.'[27]

Operation Screwdriver

Operation Screwdriver was the plan to evacuate all of the UN British Troops who were stationed in Goražde if the enclave came under attack from Bosnian Serb forces.[28] The British Prime Minister at the time, John Major, was reluctant to reinforce the town's population of roughly 30,000 and instead wanted to bring the British troops back home.[27] The operation would include an air-evacuation from Goražde using several Harrier fighter jets, 14 attack bombers and a fleet of 30 helicopters, all of which were on standby in a nearby Italian air base.[29] The operation would also involve roughly 1,500 frontline and support personnel, and was estimated to last between 10 and 15 minutes.[29] Britain had anticipated that Goražde would share the same fate as Srebrenica, and estimated the town would fall to the Serb forces in roughly 7-14 days.[27] John Major didn't want Britain to be dragged into a war with the VRS, and his senior military commander, Field Marshal Peter Inge, fully supported the operation.[27] According to its rubric, it was most likely to be used 'after a period of chaos following a major battle in which one side - most probably the Vojska Republike Srpske (Bosnian Serb Army) - has emerged victorious'.[28] By the end of the war, however, the operation had not commenced.[27]

War crimes

In October 2019, the state court in Sarajevo found Ibro Merkez guilty, as the former chief of the police’s Public Security Station in Goražde, of unlawfully detaining Serb civilians and treating them in an inhumanely manner between the middle of July 1992 and August 4 the same year.[30] Merkez was sentenced to two years in prison, while two other former policemen, Predrag Bogunić and Esef Hurić, were acquitted of all charges. Merkez was further acquitted of charges related to the period after August 4, 1992, because he was wounded and underwent medical treatment. Despite the presence of United Nations personnel throughout the siege, no member of the international community has confirmed the execution allegations as credible.[31]

In December 2021, Bosnia’s state prosecution also said that they has charged two people, Branislav Lasica and Miroslav Milović, with committing war crimes in 1992 against the civilian population of the Goražde area of eastern Bosnia, organising a group of people and incitement to the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, as well as violation of the laws and customs of war. The charges say that in their capacity as commanders of units of the Bosnian Serb Army, VRS, in that area, Lasica and Milović commanded and participated in an attack in Lozje, where around 30 people were killed. Most of the victims allegedly were civilians, including women, children and the elderly, and several dozen people were taken away and detained. Property was destroyed or appropriated on a large scale. The prosecution intends to invite 139 witnesses and introduce 251 pieces of evidence. The indictment has been filed with the state court, the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, for confirmation.[32]

Another Serb military commander, Brane Petković, was also indicted for war crimes by the Bosnian court. However, Petković failed to turn up to his court hearing on 16 June 2022. The State Court said that he had also failed to attend an earlier hearing on 10 March 2022 as well. It said that the Justice Ministry sought international legal assistance from competent bodies in the neighbouring country. The indictment, confirmed in November 2020, said that Petković – as superior officer to the commander of the District Headquarters of the Territorial Defense, TO, of Gorazde Serb Municipality, and commanders and members of the TO Municipal Headquarters’ Company – failed to prevent his subordinates from committing crimes or punish crime perpetrators – although he knew or could have known that his subordinates were either getting ready to commit or had committed crimes. During that attack, it said, seven Bosniak men were captured and taken in unknown direction and killed. Their remains were discovered in a mass grave in the village of Siseta, in Gorazde municipality, on March 17, 1993. In a report to the State Prosecution, British judge Joanna Korner wrote that the potential benefit of indicting unavailable persons is often “outweighed by the costs in time and resources”. Despite that, such practices have been followed by other prosecutors’ offices in Bosnia and Herzegovina either, as BIRN reported before.[33]

Aftermath

Goražde was the only Bosniak enclave in the Eastern Podrinje region to survive besiegement,[34] and in the Dayton Agreement in December 1995, a land bridge between Goražde and Sarajevo was opened, through the municipality of Trnovo, and the newly formed municipalities of Foča-Ustikolina and Pale-Prača. With the signing of the accords, the siege ended.

Casualties

According to the Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo (RDC), Goražde recorded 511 civilians (126 Serbs and 385 non-Serbs, mostly Bosniaks) and 1,100 soldiers who lost their lives during the war.[35] Some sources place the total number of people killed or wounded at roughly 7,000, 548 of whom were children.[17]

See also

References

- ^ E.A. (4 May 2015). "Prije 23 godine počela je opsada Goražda - grada heroja". Klix.

- ^ "Dayton Peace Accords on Bosnia". US Department of State. 30 March 1996. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2006.

- ^ Says, P. Morra (14 December 2015). "A flawed recipe for how to end a war and build a state: 20 years since the Dayton Agreement". EUROPP. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Census 2013 in Bosnia and Herzegovina". www.statistika.ba. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Popis 2013 u BiH". www.statistika.ba. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Judah, Tim (2008). The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. Yale University Press. p. 273. ISBN 9780300147841.

- ^ Lukic, Reneo; Lynch, Allen (1996). Europe from the Balkans to the Urals: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. SIPRI, Oxford University Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780198292005.

- ^ a b Ramet 2006, p. 382.

- ^ a b Ramet 2006, p. 428.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 427.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 429.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 433.

- ^ Leydesdorff, Selma (2011). Surviving the Bosnian genocide : the women of Srebrenica speak. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-253-00529-8. OCLC 756501578.

- ^ Alvarez, Alex (2010). Genocidal crimes. London. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-415-46675-2. OCLC 315238225.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Post-war protection of human rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Michael O'Flaherty, Gregory Gisvold. The Hague: M. Nijhoff Publishers. 1998. p. 107. ISBN 90-411-1020-8. OCLC 39052596.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan genocides : holocaust and ethnic cleansing in the twentieth century. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4422-0665-6. OCLC 785575178.

- ^ a b c d e "Stories from Gorazde: How One Bosnian Town Survived a Siege". Balkan Insight. 28 January 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Savo Heleta (2008). Not My Turn to Die: Memoirs of a Broken Childhood in Bosnia. AMACOM. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8144-0165-1.

- ^ СРНА (12 March 2015). "RTRS "Nova svjedočenja o stradanju Srba u Goraždu". PTPC.

- ^ Srdjan Kureljušić (19 May 2016). "Operacija Krug". Justice Report.

- ^ Sophie Haspeslagh. "The Bosnian 'Safe Havens'" (PDF). Beyondtractabiliity.org. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Bosnia: Gorazde-Trnovo, January-August 1993". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Richard J. Regan (1996). Just War: Principles and Cases. CUA Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8132-0856-5.

- ^ a b c "Serbs take 33 Britons hostage". The Independent. 28 May 1995. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ a b Br, Joel (29 May 1995). "BOSNIAN SERBS SEIZE MORE U.N. TROOPS". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Fusiliers' battle to save Bosnians". BBC. 5 December 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "'Screwdriver': The secret British plan to abandon Bosnia as Srebrenica fell". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ a b Sandford, Gillian (24 June 2001). "Surviving Serbia". the Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ a b "'High-Risk' Secret Plan To Withdraw British Troops From Bosnia Revealed". Forces Network. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Marija Tausan (25 October 2019). "Bosnian Ex-Policeman Convicted of Mistreating Serb Detainees". Balkan Transitional Justice.

- ^ Marija Tausan (25 October 2019). "Bosnian Ex-Policeman Convicted of Mistreating Serb Detainees". Balkan Transitional Justice.

- ^ "Bosnia Prosecution Indicts Two for War Crimes in Gorazde Area". Balkan Insight. 30 December 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Bosnian Court Orders Arrest Warrant Over Killings near Gorazde". Balkan Insight. 8 July 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Sandford, Gillian (24 June 2001). "Surviving Serbia". the Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Ivan Tučić (February 2013). "Pojedinačan popis broja ratnih žrtava u svim općinama BiH". Prometej.ba. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

Sources

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.