Cold Chisel: Difference between revisions

slight change |

MohammedT10 (talk | contribs) Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

Influences from blues and early rock n' roll was broadly apparent, fostered by the love of those styles by Moss, Barnes and Walker. Small and Prestwich contributed strong pop sensibilities. This allowed volatile rock songs like "You Got Nothing I Want" and "Merry-Go-Round" to stand beside thoughtful ballads like "Choirgirl", pop-flavoured love songs like "My Baby" and caustic political statements like "Star Hotel", an attack on the late 1970s government of [[Malcolm Fraser]], inspired by the [[Star Hotel riot]] in [[Newcastle, Australia|Newcastle]]. |

Influences from blues and early rock n' roll was broadly apparent, fostered by the love of those styles by Moss, Barnes and Walker. Small and Prestwich contributed strong pop sensibilities. This allowed volatile rock songs like "You Got Nothing I Want" and "Merry-Go-Round" to stand beside thoughtful ballads like "Choirgirl", pop-flavoured love songs like "My Baby" and caustic political statements like "Star Hotel", an attack on the late 1970s government of [[Malcolm Fraser]], inspired by the [[Star Hotel riot]] in [[Newcastle, Australia|Newcastle]]. |

||

The songs were not overtly political but rather observations of everyday life within Australian society and culture, in which the members with their various backgrounds (Moss was from [[Alice Springs, Australia|Alice Springs]], Walker grew up in rural New South Wales, Barnes and Prestwich were working-class immigrants from the UK) were quite well able to provide.{{Citation needed|date=October 2019}} |

The songs were not overtly political but rather observations of everyday life within Australian society and culture, in which the members with their various backgrounds (Moss was from [[Alice Springs, Australia|Alice Springs]], Walker grew up in rural New South Wales, Barnes and Prestwich were working-class immigrants from the UK) were quite well able to provide.{{Citation needed|date=October 2019}}<ref>Freedom Songs: the role of music in the anti-apartheid struggle - PART A - Anti Apartheid Legacy</ref> |

||

Cold Chisel's songs were about distinctly Australian experiences, a factor often cited as a major reason for the band's lack of international appeal. "Saturday Night" and "Breakfast at Sweethearts" were observations of the urban experience of Sydney's [[Kings Cross, New South Wales|Kings Cross]] district where Walker lived for many years. "Misfits", which featured on the b-side to "My Baby", was about homeless kids in the suburbs surrounding Sydney. Songs like "Shipping Steel" and "Standing on The Outside" were working class anthems and many others featured characters trapped in mundane, everyday existences, yearning for the good times of the past ("Flame Trees") or for something better from life ("Bow River"). |

Cold Chisel's songs were about distinctly Australian experiences, a factor often cited as a major reason for the band's lack of international appeal. "Saturday Night" and "Breakfast at Sweethearts" were observations of the urban experience of Sydney's [[Kings Cross, New South Wales|Kings Cross]] district where Walker lived for many years. "Misfits", which featured on the b-side to "My Baby", was about homeless kids in the suburbs surrounding Sydney. Songs like "Shipping Steel" and "Standing on The Outside" were working class anthems and many others featured characters trapped in mundane, everyday existences, yearning for the good times of the past ("Flame Trees") or for something better from life ("Bow River"). |

||

Revision as of 14:15, 29 June 2024

Cold Chisel | |

|---|---|

Don Walker, Ian Moss, Jimmy Barnes, Charley Drayton (behind him) and Phil Small at AIS Arena, Canberra in November 2011 | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as |

|

| Origin | Adelaide, South Australia |

| Genres | |

| Years active |

|

| Labels |

|

| Members | |

| Past members | See members |

| Website | coldchisel |

Cold Chisel are an Australian pub rock band, which formed in Adelaide in 1973 by mainstay members Ian Moss on guitar and vocals, Steve Prestwich on drums and Don Walker on piano and keyboards. They were soon joined by Jimmy Barnes (at the time known as Jim Barnes) on lead vocals and, in 1975, Phil Small became their bass guitarist. The group disbanded in late 1983 but subsequently reformed several times. Musicologist Ian McFarlane wrote that they became "one of Australia's best-loved groups" as well as "one of the best live bands", fusing "a combination of rockabilly, hard rock and rough-house soul'n'blues that was defiantly Australian in outlook."

Eight of their studio albums have reached the Australian top five, Breakfast at Sweethearts (February 1979), East (June 1980), Circus Animals (March 1982, No. 1), Twentieth Century (April 1984, No. 1), The Last Wave of Summer (October 1998, No. 1), No Plans (April 2012), The Perfect Crime (October 2015) and Blood Moon (December 2019, No. 1). Their top 10 singles are "Forever Now" (1982), "Hands Out of My Pocket" (1994) and "The Things I Love in You" (1998).

At the ARIA Music Awards of 1993 they were inducted into the Hall of Fame. In 2001 Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA), listed their single, "Khe Sanh" (May 1978), at No. 8 of the all-time best Australian songs. Circus Animals was listed at No. 4 in the book, 100 Best Australian Albums (October 2010), while East appeared at No. 53. They won The Ted Albert Award for Outstanding Services to Australian Music at the APRA Music Awards of 2016. Cold Chisel's popularity is almost entirely confined to Australia and New Zealand, with their songs and musicianship highlighting working class life. Their early bass guitarist (1973–75), Les Kaczmarek, died in December 2008; Steve Prestwich died of a brain tumour in January 2011.

History

1973–1978: Beginnings

Cold Chisel originally formed as Orange in Adelaide in 1973 as a heavy metal band by Ted Broniecki on keyboards, Les Kaczmarek on bass guitar, Ian Moss on guitar and vocals, Steve Prestwich on drums and Don Walker on piano.[1][2][3] Their early material included cover versions of Free and Deep Purple material.[1][3] Broniecki left by September 1973 and seventeen-year-old singer, Jimmy Barnes – called Jim Barnes during their initial career – joined in December.[1][3]

The group changed its name several times before settling on Cold Chisel in 1974 after Walker's song of that title.[4] Barnes' relationship with the others was volatile: he often came to blows with Prestwich and left the band several times.[3][4] During these periods Moss would handle vocals until Barnes returned.[4] Walker emerged as the group's primary songwriter and spent 1974 in Armidale, completing his studies in quantum mechanics.[1][4] Barnes' older brother, John Swan, was a member of Cold Chisel around this time, providing backing vocals and percussion.[1][2][4] After several violent incidents, including beating up a roadie, he was fired.[4][5] In mid-1975 Barnes left to join Fraternity as Bon Scott's replacement on lead vocals, alongside Swan on drums and vocals.[2][5][6][7]

Kaczmarek left Cold Chisel during 1975 and was replaced by Phil Small on bass guitar.[1][2] In November of that year, without Barnes, they recorded their early demos.[4]

In May 1976 Cold Chisel relocated to Melbourne, but "frustrated by their lack of progress,"[4] they moved on to Sydney in early 1977.[8] In May 1977, Barnes told his fellow members that he would leave again. From July he joined Feather for a few weeks, on co-lead vocals with Swan – they were a Sydney-based hard rock group, which had evolved from Blackfeather.[2][9] A farewell performance for Cold Chisel, with Barnes aboard, went so well that the singer changed his mind and returned.[5] In the following month the Warner Music Group signed the group.[5]

1978–1979: Cold Chisel and Breakfast at Sweethearts

In the early months of 1978 Cold Chisel recorded their self-titled debut album with their manager and producer, Peter Walker (ex-Bakery).[1][2][4] All tracks were written by Don Walker, except "Juliet", where Barnes composed its melody and Walker the lyrics.[10] Cold Chisel was released in April and included guest studio musicians: Dave Blight on harmonica (who became a regular on-stage guest) and saxophonists Joe Camilleri and Wilbur Wilde (from Jo Jo Zep & The Falcons). Australian musicologist, Ian McFarlane, described how, "[it] failed to capture the band's renowned live firepower, despite the presence of such crowd favourites as 'Khe Sanh', 'Home and Broken Hearted' and 'One Long Day'."[1] It reached the top 40 on the Kent Music Report and was certified gold.[8]

In May 1978, "Khe Sanh", was released as their debut single but it was declared too offensive for commercial radio due to the sexual implication of the lyrics, e.g. "Their legs were often open/But their minds were always closed."[4][11] However, it was played regularly on Sydney youth radio station, Double J, which was not subject to the restrictions as it was part of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). Another ABC program, Countdown's producers asked them to change the lyric but they refused.[4] Despite such setbacks, "Khe Sanh" reached No. 41 on the Kent Music Report singles chart.[12] It became Cold Chisel's signature tune and was popular among their fans. They later remixed the track, with re-recorded vocals, for inclusion on the international version of their third album, East (June 1980).

The band's next release was a live five-track extended play, You're Thirteen, You're Beautiful, and You're Mine, in November 1978.[1][12] McFarlane observed, "It captured the band in its favoured element, fired by raucous versions of Walker's 'Merry-Go-Round' and Chip Taylor's 'Wild Thing'."[1] It was recorded at the Regent Theatre, Sydney in 1977, when they had Midnight Oil as one of the support acts. Australian writer, Ed Nimmervoll, described a typical performance by Cold Chisel, "Everybody was talking about them anyway, drawn by the songs, and Jim Barnes' presence on stage, crouched, sweating, as he roared his vocals into the microphone at the top of his lungs."[4] The EP peaked at No. 35 on the Kent Music Report Singles Chart.[1][12]

"Merry Go Round" was re-recorded for their second studio album, Breakfast at Sweethearts (February 1979). This was recorded between July 1978 and January 1979 with producer, Richard Batchens, who had previously worked with Richard Clapton, Sherbet and Blackfeather.[1][2][4] Batchens smoothed out the band's rough edges and attempted to give their songs a sophisticated sound.[4] With regards to this approach, the band were unsatisfied with the finished product.[13] It peaked at No. 4 and was the top selling album in Australia by a locally based artist for that year;[1][12] it was certified platinum.[8] The majority of its tracks were written by Walker, with Barnes and Walker on the lead single, "Goodbye (Astrid, Goodbye)" (September 1978), and Moss contributed to "Dresden". "Goodbye (Astrid, Goodbye)" became a live favourite, and was covered by U2 during Australian tours in the 1980s.

1979-1980: East

Cold Chisel had gained national chart success and increased popularity of their fans without significant commercial radio airplay. The members developed reputations for wild behaviour, particularly Barnes who claimed to have had sex with over 1000 women and who consumed more than a bottle of vodka each night while performing.[5] In late 1979, severing their relationship with Batchens, Cold Chisel chose Mark Opitz to produce the next single, "Choirgirl" (November).[1][12] It is a Walker composition dealing with a young woman's experience with abortion. Despite the subject matter it reached No. 14.[12]

"Choirgirl" paved the way for the group's third studio album, East (June 1980), with Opitz producing.[2] Recorded over two months in early 1980, East, reached No. 2 and is the second highest selling album by an Australian artist for that year.[1][12] The Australian Women's Weekly's Gregg Flynn noticed, "[they are] one of the few Australian bands in which each member is capable of writing hit songs."[14] Despite the continued dominance of Walker, the other members contributed more tracks to their play list, and this was their first album to have songs written by each one.[1] McFarlane described it as, "a confident, fully realised work of tremendous scope."[1] Nimmervoll explained how, "This time everything fell into place, the sound, the songs, the playing... East was a triumph. [The group] were now the undisputed No. 1 rock band in Australia."[4]

The album varied from straight ahead rock tracks, "Standing on the Outside" and "My Turn to Cry", to rockabilly-flavoured work-outs ("Rising Sun", written about Barnes' relationship with his then-girlfriend Jane Mahoney) and pop-laced love songs ("My Baby" by Phil Small, featuring Joe Camilleri on saxophone) to a poignant piano ballad about prison life, "Four Walls". The cover art showed Barnes reclined in a bathtub wearing a kamikaze bandanna in a room littered with junk and was inspired by Jacques-Louis David's 1793 painting, The Death of Marat.[4] The Ian Moss-penned "Never Before" was chosen as the first song to air on the ABC's youth radio station, Triple J, when it switched to the FM band that year. Supporting the release of East, Cold Chisel embarked on the Youth in Asia Tour from May 1980, which took its name from a lyric in "Star Hotel".

In late 1980, the Aboriginal rock reggae band No Fixed Address supported the band on its "Summer Offensive" tour to the east coast, with the final concert on 20 December at the University of Adelaide.[15][16]

1981-1982: Swingshift to Circus Animals

The Youth in Asia Tour performances were used for Cold Chisel's double live album, Swingshift (March 1981).[1] Nimmervoll declared, "[the group] rammed what they were all about with [this album]."[4] In March 1981 the band won seven categories: Best Australian Album, Most Outstanding Achievement, Best Recorded Song Writer, Best Australian Producer, Best Australian Record Cover Design, Most Popular Group and Most Popular Record, at the Countdown/TV Week pop music awards for 1980.[17][18][19] They attended the ceremony at the Sydney Entertainment Centre and were due to perform: however, as a protest against a TV magazine's involvement, they refused to accept any trophy and finished the night with, "My Turn to Cry".[17][18][19] After one verse and chorus, they smashed up the set and left the stage.[20]

Swingshift debuted at No 1,[1][12] which demonstrated their status as the highest selling local act.[1][4] With a slightly different track-listing, East, was issued in the United States and they undertook their first US tour in mid-1981.[1][4] Ahead of the tour they had issued, "My Baby", for the North America market and it reached the top 40 on Billboard's chart, Mainstream Rock.[21] They were generally popular as a live act there, but the US branch of their label did little to promote the album.[5] According to Barnes' biographer, Toby Creswell, at one point they were ushered into an office to listen to the US master tape to find it had substantial hiss and other ambient noise,[5] which made it almost unable to be released. Notwithstanding, the album reached the lower region of the Billboard 200 in July.[22] The group were booed off stage after a lacklustre performance in Dayton, Ohio in May 1981 opening for Ted Nugent. Other support slots they took were for Cheap Trick, Joe Walsh, Heart and the Marshall Tucker Band.[1] European audiences were more accepting of the Australian band and they developed a fan base in Germany.

In August 1981 Cold Chisel began work on a fourth studio album, Circus Animals (March 1982), again with Opitz producing.[1][2] To launch the album, the band performed under a circus tent at Wentworth Park in Sydney and toured heavily once more, including a show in Darwin that attracted more than 10 percent of the city's population.[20] It peaked at No. 1 in both Australia and on the Official New Zealand Music Chart.[12][23] In October 2010 it was listed at No. 4 in the book, 100 Best Australian Albums, by music journalists, Creswell, Craig Mathieson and John O'Donnell.[24]

Its lead single, "You Got Nothing I Want" (November 1981), is an aggressive Barnes-penned hard rock track, which attacked the US industry for its handling of the band on their recent tour.[25] The song caused problems for Barnes when he later attempted to break into the US market as a solo performer; senior music executives there continued to hold it against him. Like its predecessor, Circus Animals, contained songs of contrasting styles, with harder-edged tracks like "Bow River" and "Hound Dog" in place beside more expansive ballads such as the next two singles, "Forever Now" (March 1982) and "When the War Is Over" (August), both are written by Prestwich.[1][4][25] "Forever Now" is their highest charting single in two Australasian markets: No. 4 on the Kent Music Report Singles Chart and No. 2 on the Official New Zealand Music Chart.[12][23]

"When the War Is Over" is the most covered Cold Chisel track – Uriah Heep included a version on their 1989 album, Raging Silence; John Farnham recorded it while he and Prestwich were members of Little River Band in the mid-1980s and again for his 1990 solo album, Age of Reason. The song was also a No. 1 hit for former Australian Idol contestant, Cosima De Vito, in 2004 and was performed by Bobby Flynn during that show's 2006 season. "Forever Now" was covered, as a country waltz, by Australian band, the Reels.

1983: Break-up

Success outside Australasia continued to elude Cold Chisel and friction occurred between the members. According to McFarlane, "[the] failed attempts to break into the American market represented a major blow... [their] earthy, high-energy rock was overlooked."[1] In early 1983 they toured Germany but the shows went so badly that in the middle of the tour Walker up-ended his keyboard and stormed off stage during one show. After returning to Australia, Prestwich was fired and replaced by Ray Arnott, formerly of the 1970s progressive rockers, Spectrum, and country rockers, the Dingoes.[1][2][26]

After this, Barnes requested a large advance from management. Now married with a young child, reckless spending had left him almost broke. His request was refused as there was a standing arrangement that any advance to one band member had to be paid to all the others. After a meeting on 17 August during which Barnes quit the band it was decided that the group would split up.[20] A farewell concert series, The Last Stand, was planned and a final studio album, Twentieth Century (February 1984), was recorded.[1][2][20] Prestwich returned for that tour, which began in October.[20] Before the last four scheduled shows in Sydney, Barnes lost his voice and those dates were postponed to mid-December.[20][27]

The band's final performances were at the Sydney Entertainment Centre from 12 to 15 December 1983[27] – ten years since their first live appearance as Cold Chisel in Adelaide – and the group then disbanded.[1][2][4] The Sydney shows formed the basis of a concert film, The Last Stand (July 1984), which became the biggest-selling cinema-released concert documentary by an Australian band to that time. Other recordings from the tour were used on a live album, The Barking Spiders Live: 1983 (1984), the title is a reference to the pseudonym the group occasionally used when playing warm-up shows before tours. Some were also used as b-sides for a three-CD singles package, Three Big XXX Hits, issued ahead of the release of their 1994 compilation album, Teenage Love.

During breaks in the tour, Twentieth Century was recorded. It was a fragmentary process, spread across various studios and sessions as the individual members often refused to work together – both Arnott (on ten tracks) and Prestwich (on three tracks) are recorded as drummers. The album reached No. 1 and provided the singles "Saturday Night" (March 1984) and "Flame Trees" (August), both of which remain radio staples. "Flame Trees", co-written by Prestwich and Walker, took its title from the BBC series The Flame Trees of Thika, although it was lyrically inspired by Walker's hometown of Grafton. Barnes later recorded an acoustic version for his 1993 solo album, Flesh and Wood, and it was also covered by Sarah Blasko in 2006.

1984-1996: Aftermath and ARIA Hall of Fame

Barnes launched his solo career in January 1984, which has provided nine Australian number-one studio albums and an array of hit singles, including "Too Much Ain't Enough Love", which peaked at No. 1. He has recorded with INXS, Tina Turner, Joe Cocker and John Farnham to become one of the country's most popular male rock singers. Prestwich joined Little River Band in 1984 and appeared on the albums Playing to Win and No Reins, before departing in 1986 to join Farnham's touring band. Moss, Small and Walker took extended breaks from music.

Small maintained a low profile as a member in a variety of minor groups Pound, the Earls of Duke and the Outsiders.[1][2][4] Walker formed Catfish in 1988, ostensibly a solo band with a variable membership, which included Moss, Charlie Owen and Dave Blight at times.[1][2][4] Catfish's recordings during this phase attracted little commercial success. During 1988 and 1989 Walker wrote several tracks for Moss including the singles "Tucker's Daughter" (November 1988) and "Telephone Booth" (June 1989), which appeared on Moss' debut solo album, Matchbook (August 1989).[1][2][28] Both the album and "Tucker's Daughter" peaked at No. 1.[28][29] Moss won five trophies at the ARIA Music Awards of 1990.[28][30] His other solo albums met with less chart or award success.[28]

Throughout the 1980s and most of the 1990s, Cold Chisel were courted to re-form but refused, at one point reportedly turning down a $5 million offer to play a sole show in each of the major Australian state capitals. Moss and Walker often collaborated on projects; neither worked with Barnes until Walker wrote "Stone Cold" for the singer's sixth studio album, Heat (October 1993). The pair recorded an acoustic version for Flesh and Wood (December). Thanks primarily to continued radio airplay and Barnes' solo success, Cold Chisel's legacy remained solidly intact.[1][2][31] By the early 1990s the group had surpassed 3 million album sales, most sold since 1983.[1] The 1991 compilation album, Chisel, was re-issued and re-packaged several times, once with the long-deleted 1978 EP as a bonus disc and a second time in 2001 as a double album. The Last Stand soundtrack album was finally released in 1992. In 1994 a complete album of previously unreleased demo and rare live recordings, Teenage Love, was released, which provided three singles.

1997–2010: Reunited

Cold Chisel reunited in October 1997, with the line-up of Barnes, Moss, Prestwich, Small and Walker.[1][2] They recorded their sixth studio album, The Last Wave of Summer (October 1998), from February to July with the band members co-producing.[1][2][4] They supported it with a national tour. The album debuted at No. 1 on the ARIA Albums Chart.[32] In 2003 they re-grouped for the Ringside Tour and in 2005 again to perform at a benefit for the victims of the Boxing Day tsunami at the Myer Music Bowl in Melbourne. Founding bass guitarist, Les Kaczmarek, died of liver failure on 5 December 2008, aged 53.[33] Walker described him as "a wonderful and beguiling man in every respect."[34]

On 10 September 2009 Cold Chisel announced they would reform for a one-off performance at the Sydney 500 V8 Supercars event on 5 December.[35] The band performed at Stadium Australia to the largest crowd of its career, with more than 45,000 fans in attendance.[36] They played a single live show in 2010: at the Deniliquin ute muster in October. In December Moss confirmed that Cold Chisel were working on new material for an album.

2011–2019: Death of Steve Prestwich & The Perfect Crime

In January 2011 Steve Prestwich was diagnosed with a brain tumour; he underwent surgery on 14 January but never regained consciousness and died two days later, aged 56.[37] All six of Cold Chisel's studio albums were re-released in digital and CD formats in mid-2011. Three digital-only albums were released – Never Before, Besides and Covered – as well as a new compilation album, The Best of Cold Chisel: All for You, which peaked at No. 2 on the ARIA Charts.[32] The thirty-date Light the Nitro Tour was announced in July along with the news that former Divinyls and Catfish drummer, Charley Drayton, had replaced Prestwich. Most shows on the tour sold out within days and new dates were later announced for early 2012.

No Plans, their seventh studio album, was released in April 2012, with Kevin Shirley producing,[38] which peaked at No. 2.[32] The Australian's Stephen Fitzpatrick rated it as four-and-a-half out of five and found its lead track, "All for You", "speaks of redemption; of a man's ability to make something of himself through love."[39] The track "I Got Things to Do" was written and sung by Prestwich, which Fitzpatrick described as "the bittersweet finale", a song that had "a vocal track the other band members did not know existed until after [Prestwich's] death."[39] Midway through 2012 they embarked on a short UK tour and played with Soundgarden and Mars Volta at Hard Rock Calling at London's Hyde Park.[40][41]

The group's eighth studio album, The Perfect Crime, appeared in October 2015, again with Shirley producing, which peaked at No. 2.[32][42] Martin Boulton of The Sydney Morning Herald rated it at four out of five stars and explained that the album does what Cold Chisel always does: "work incredibly hard, not take any shortcuts and play the hell out of the songs." The album, Boulton writes, "delves further back to their rock'n'roll roots with chief songwriter [Walker] carving up the keys, guitarist [Moss] both gritty and sublime and the [Small/Drayton] engine room firing on every cylinder. Barnes' voice sounds worn, wonderful and better than ever."[43]

The band's latest album, Blood Moon, was released in December 2019. The album debuted at No. 1 on the ARIA Album Chart, the band's fifth to reach the top.[44] Half of the songs had lyrics written by Barnes and music by Walker,[45] a new combination for Cold Chisel, with Barnes noting his increased confidence after writing two autobiographies.[46]

2024: 50th Anniversary Tour

On 29 May 2024, Cold Chisel announced 'The 50th Anniversary Tour'.[47] With the tour beginning in Armidale on 5 October 2024 and scheduled to end in the band's hometown of Adelaide on 17 November 2024. However Jimmy Barnes' wife Jane subsequently posted on X.com, that further tour dates including New Zealand would be announced later.[48]

Musical style and lyrical themes

McFarlane described Cold Chisel's early career in his Encyclopedia of Australian Rock and Pop (1999), "after ten years on the road, [they] called it a day. Not that the band split up for want of success; by that stage [they] had built up a reputation previously uncharted in Australian rock history. By virtue of the profound effect the band's music had on the many thousands of fans who witnessed its awesome power, Cold Chisel remains one of Australia's best-loved groups. As one of the best live bands of its day, [they] fused a combination of rockabilly, hard rock and rough-house soul'n'blues that was defiantly Australian in outlook."[1] The Canberra Times' Luis Feliu, in July 1978, observed how, "This is not just another Australian rock band, no mediocrity here, and their honest, hard-working approach looks like paying off."[49] While "the range of styles tackled and done convincingly, from hard rock to blues, boogie, rhythm and blues, is where the appeal lies."[49]

Influences from blues and early rock n' roll was broadly apparent, fostered by the love of those styles by Moss, Barnes and Walker. Small and Prestwich contributed strong pop sensibilities. This allowed volatile rock songs like "You Got Nothing I Want" and "Merry-Go-Round" to stand beside thoughtful ballads like "Choirgirl", pop-flavoured love songs like "My Baby" and caustic political statements like "Star Hotel", an attack on the late 1970s government of Malcolm Fraser, inspired by the Star Hotel riot in Newcastle.

The songs were not overtly political but rather observations of everyday life within Australian society and culture, in which the members with their various backgrounds (Moss was from Alice Springs, Walker grew up in rural New South Wales, Barnes and Prestwich were working-class immigrants from the UK) were quite well able to provide.[citation needed][50]

Cold Chisel's songs were about distinctly Australian experiences, a factor often cited as a major reason for the band's lack of international appeal. "Saturday Night" and "Breakfast at Sweethearts" were observations of the urban experience of Sydney's Kings Cross district where Walker lived for many years. "Misfits", which featured on the b-side to "My Baby", was about homeless kids in the suburbs surrounding Sydney. Songs like "Shipping Steel" and "Standing on The Outside" were working class anthems and many others featured characters trapped in mundane, everyday existences, yearning for the good times of the past ("Flame Trees") or for something better from life ("Bow River").

Reputation and recognition

Alongside contemporaries like The Angels and Midnight Oil, Cold Chisel was renowned as one of the most dynamic live acts of their day and from early in their career concerts routinely became sell-out events. But the band was also famous for its wild lifestyle, particularly the hard-drinking Barnes, who played his role as one of the wild men of Australian rock to the hilt, never seen on stage without at least one bottle of vodka and often so drunk he could barely stand upright. Despite this, by 1982 he was a devoted family man who refused to tour without his wife and daughter. All the other band members were also settled or married; Ian Moss had a long-term relationship with the actress, Megan Williams, (she even sang on Twentieth Century) whose own public persona could have hardly been more different.

It was the band's public image that often had them compared less favourably with other important acts like Midnight Oil, whose music and politics (while rather more overt) were often similar but whose image and reputation was more clean-cut. Cold Chisel remained hugely popular however and by the mid-1990s they continued to sell records at such a consistent rate they became the first Australian band to achieve higher sales after their split than during their active years.[1]

At the ARIA Music Awards of 1993 they were inducted into the Hall of Fame.[51] While repackages and compilations accounted for much of these sales, 1994's Teenage Love provided two of its singles, which were top ten hits. When the group finally reformed in 1998 the resultant album was also a major hit and the follow-up tour sold out almost immediately. In 2001 Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA), listed their single, "Khe Sanh" (May 1978), at No. 8 of the all-time best Australian songs.[52]

Cold Chisel were one of the first Australian acts to have become the subject of a major tribute album. In 2007, Standing on the Outside: The Songs of Cold Chisel was released, featuring a collection of the band's songs as performed by artists including The Living End, Evermore, Something for Kate, Pete Murray, Katie Noonan, You Am I, Paul Kelly, Alex Lloyd, Thirsty Merc and Ben Lee,[53] many of whom were children when Cold Chisel first disbanded and some, like the members of Evermore, had not even been born. Circus Animals was listed at No. 4 in the book, 100 Best Australian Albums (October 2010), while East appeared at No. 53.[24] They won The Ted Albert Award for Outstanding Services to Australian Music at the APRA Music Awards of 2016.[54]

In March 2021, a previously unnamed lane off Burnett Street (off Currie Street) in the Adelaide central business district, near where the band had its first residency in the 1970s, was officially named Cold Chisel Lane. On one of its walls, there is a 50-metre (160 ft) mural by Adelaide artist James Dodd, inspired by the band.[55][56]

Members

|

Current members

Former members

|

Additional musicians

|

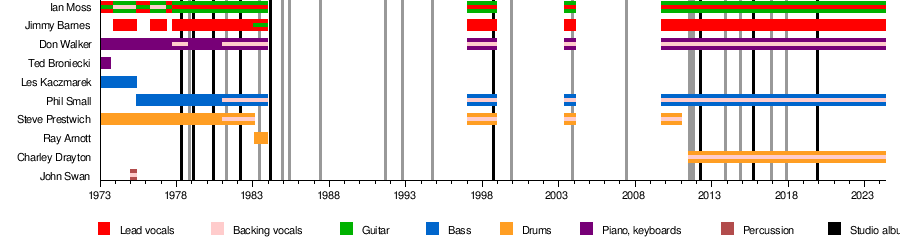

Timeline

Discography

- Cold Chisel (1978)

- Breakfast at Sweethearts (1979)

- East (1980)

- Circus Animals (1982)

- Twentieth Century (1984)

- The Last Wave of Summer (1998)

- No Plans (2012)

- The Perfect Crime (2015)

- Blood Moon (2019)[57]

Awards and nominations

APRA Awards

The APRA Awards are presented annually from 1982 by the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA), "honouring composers and songwriters". They commenced in 1982.[58]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | "All for You" (Don Walker) | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [59] |

| 2016 | "Lost" (Don Walker, Wes Carr) | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [60] |

| 2021 | "Getting the Band Back Together" (Don Walker) | Most Performed Rock Work | Won | [61][62] |

| Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [63] |

ARIA Music Awards

The ARIA Music Awards is an annual awards ceremony that recognises excellence, innovation, and achievement across all genres of Australian music. They commenced in 1987. Cold Chisel was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1993.[64]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Chisel | Highest Selling Album | Nominated |

| 1993 | Cold Chisel | ARIA Hall of Fame | inductee |

| 1999 | The Last Wave of Summer | Best Rock Album | Nominated |

| Highest Selling Album | Nominated | ||

| 2012 | No Plans | Best Rock Album | Nominated |

| Best Group | Nominated | ||

| Light The Nitro Tour | Best Australian Live Act | Nominated | |

| 2020 | Blood Moon | Best Rock Album | Nominated |

| Kevin Shirley for Blood Moon by Cold Chisel | Producer of the Year | Nominated | |

| Blood Moon Tour | Best Australian Live Act | Nominated |

Helpmann Awards

The Helpmann Awards is an awards show, celebrating live entertainment and performing arts in Australia, presented by industry group Live Performance Australia since 2001.[65] Note: 2020 and 2021 were cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Light the Nitro Tour | Best Australian Contemporary Concert | Nominated | [66] |

South Australian Music Awards

The South Australian Music Awards are annual awards that exist to recognise, promote and celebrate excellence in the South Australian contemporary music industry. They commenced in 2012. The South Australian Music Hall of Fame celebrates the careers of successful music industry personalities.[67]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Cold Chisel | Hall of Fame | inductee | [68] |

TV Week / Countdown Awards

Countdown was an Australian pop music TV series on national broadcaster ABC-TV from 1974–1987, it presented music awards from 1979–1987, initially in conjunction with magazine TV Week. The TV Week / Countdown Awards were a combination of popular-voted and peer-voted awards.[69]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Breakfast at Sweethearts | Best Australian Album | Nominated |

| Best Australian Record Cover Design | Won | ||

| Don Walker for "Choirgirl" by Cold Chisel | Best Recorded Songwriter | Nominated | |

| 1980 | East | Best Australian Album | Won |

| Best Australian Record Cover Design | Won | ||

| Most Popular Australia Album | Won | ||

| Cold Chisel | Most Outstanding Achievement | Won | |

| Most Popular Group | Won | ||

| Jimmy Barnes (Cold Chisel) | Most Popular Male Performer | Nominated | |

| Don Walker by Cold Chisel | Best Recorded Songwriter | Won | |

| Mark Opitz for East by Cold Chisel | Best Australian Producer | Won | |

| 1981 | themselves | Most Consistent Live Act | Won |

| 1982 | Circus Animals | Best Australian Album | Nominated |

| 1984 | "Saturday Night" | Best Video | Nominated |

See also

References

- General

- McFarlane, Ian (1999). "Whammo Homepage". Encyclopedia of Australian Rock and Pop. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-072-1. Archived from the original on 5 April 2004. Retrieved 3 October 2013. Note: Archived [on-line] copy has limited functionality.

- Specific

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak McFarlane, 'Cold Chisel' entry. Archived from the original on 19 April 2004. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Entries at Australian Rock Database:

- Cold Chisel: – Holmgren, Magnus; Shoppee, Philip; Meyer, Peer. "Cold Chisel". hem2.passagen.se. Australian Rock Database (Magnus Holmgren). Archived from the original on 3 March 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Ray Arnott (1983): – Holmgren, Magnus; McCulloch, Barry; Jensen, Neil. "Ray Arnott". hem2.passagen.se. Australian Rock Database (Magnus Holmgren). Archived from the original on 4 March 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Jimmy Barnes (1973–75, 1976–77, 1977–83, 1997–99, 2003): – Holmgren, Magnus; Shoppee, Philip; Meyer, Peer. "Jimmy Barnes". hem2.passagen.se. Australian Rock Database (Magnus Holmgren). Archived from the original on 14 February 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Ian Moss (1973–83, 1997–99, 2003): – Holmgren, Magnus; Zsigri, Eva; Withers, Jerome. "Ian Moss". hem2.passagen.se. Australian Rock Database (Magnus Holmgren). Archived from the original on 11 April 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Steve Prestwich (1973–83, 1983, 1997–99, 2003): – Holmgren, Magnus; Hooper, Craig. "Steve Prestwich". hem2.passagen.se. Australian Rock Database (Magnus Holmgren). Archived from the original on 12 April 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- John Swan (1974, 1975): – Holmgren, Magnus; Meyer, Peer; Ashton, Gwyn. "Swanee/John Swan". hem2.passagen.se. Australian Rock Database (Magnus Holmgren). Archived from the original on 8 March 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Don Walker (1973–83, 1997–99, 2003): – Holmgren, Magnus; Clarke, Gordon; Cleeland, Jason; Withers, Jerome. "Don Walker". hem2.passagen.se. Australian Rock Database (Magnus Holmgren). Archived from the original on 1 March 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Shedden, Iain (18 January 2011). "Last wave of summer for Cold Chisel drummer Steve Prestwich". The Australian. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Nimmervoll, Ed. "Cold Chisel". Howlspace – The Living History of Our Music. White Room Electronic Publishing Pty Ltd (Ed Nimmervoll). Archived from the original on 28 July 2003. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Creswell, Toby Jimmy Barnes: Too Much Ain't Enough (1993)

- ^ McFarlane, 'Fraternity' entry. Archived from the original on 28 August 2004. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Organisation, Grape. "Jimmy Barnes". Fraternity. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "New Faces to Watch" (PDF). Cash Box. 18 July 1981. p. 8. Retrieved 1 December 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ McFarlane, 'Feather' entry. Archived from the original on 6 August 2004. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "'Juliet' at APRA search engine". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA). Retrieved 8 May 2018. Note: For additional work user may have to select 'Search again' and then 'Enter a title:' &/or 'Performer:'

- ^ McGrath, Noel The Australian Encyclopaedia of Rock and Pop (1983)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book Ltd. p. 72. ISBN 0-646-11917-6. Note: Used for Australian Singles and Albums charting from 1974 until Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) created their own charts in mid-1988. In 1992, Kent back calculated chart positions for 1970–1974.

- ^ Dan Lander (November 2015). "Meeting of the Minds". Rolling Stone Australia. No. 768. Paper Riot Pty Ltd. pp. 52–57.

- ^ Flynn, Gregg (3 September 1980). "The quiet man of Cold Chisel". The Australian Women's Weekly. Your TV Magazine. Vol. 48, no. 14. p. 13. Retrieved 8 May 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "No Fixed Address Lane" (Includes map). Alpaca Travel. City of Music Laneways. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Gig History 1980's". Cold Chisel. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ a b Warner, Dave (June 2006). Countdown: the wonder years 1974–1987. Sydney, NSW: ABC Books (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). ISBN 0-7333-1401-5.

- ^ a b Kimball, Duncan (2002). "Media – Television – Countdown". Milesago: Australasian Music and Popular Culture 1964–1975. Ice Productions. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Countdown Show no.:241 Date: 22/3/1981". Countdown Archives. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Creswell, Toby and Fabinyi, Martin The Real Thing

- ^ "Cold Chisel – Chart history (Mainstream Rock)". Billboard. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Cold Chisel – Chart history (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b Hung, Steffen. "Cold Chisel – Circus Animals". New Zealand Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b O'Donnell, John; Creswell, Toby; Mathieson, Craig (October 2010). 100 Best Australian Albums. Prahran: Hardie Grant Books. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-1-74066-955-9.

- ^ a b Zupp, Adrian. "Circus Animals – Cold Chisel Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Lawrence, Michael (2012). Cold Chisel: Wild Colonial Boys. Melbourne: Melbourne Books. p. 211. ISBN 9781877096174.

- ^ a b Perry, Lisa (2 November 1983). "Timespan: Chisel farewell delayed so Barnes can give his best". The Canberra Times. Vol. 58, no. 17, 566. p. 24. Retrieved 10 May 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d McFarlane, "'Ian Moss' entry". Archived from the original on 28 June 2004. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "Discography Ian Moss". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "Winners by Year 1990". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ McFarlane, "'Jimmy Barnes' entry". Archived from the original on 3 August 2004. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d Hung, Steffen. "Discography Cold Chisel". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Cashmere, Paul (9 December 2008). "Brendan Ozolins Pays Tribute to Les Kaczmarek". Undercover News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Walker, Don (5 April 2016). "Don Walker for Cold Chisel: 'There are four of us in the band up here, and there should be five' APRA Ted Albert award – 2016". Speakola. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ McCabe, Kathy (11 September 2009). "Cold Chisel Reform for Sydney Telstra 500 V8 Supercars Series at Olympic Park". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ^ "Cold Chisel rock race fans". Stadium Australia. 5 December 2009. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ Levy, Megan (18 January 2011). "Australian music industry in mourning over Chisel, Sherbet deaths". The Age. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Condon, Dan (1 May 2012). "Cold Chisel – No Plans". themusic.com.au. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, Stephen (7 April 2012). "No Plans (Cold Chisel)". The Australian. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Harte, Lee (16 July 2012). "Cold Chisel – a very special blast from the past". Australian Times. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Cold Chisel to play London's Hyde Park for Hard Rock Calling". Australian Times. 27 March 2012. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Bell, Steve (2 October 2015). "We Are Legend: How Cold Chisel Became so Much Greater than the Sum of Their Parts". the.music.au. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Boulton, Martin (24 September 2015). "Album Reviews: Cold Chisel, Metric, Kurt Vile, Clutch, Big Boi & Phantogram". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Cold Chisel Blood Moon Is No 1 38 Years After Swingshift In 1981". noise11. 14 December 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ "Blood brothers: An interview with Cold Chisel". Stack. 5 December 2019.

- ^ "Cold Chisel". Amnplify. 6 December 2019.

- ^ "COLD CHISEL announce 50th Anniversary Tour". coldchisel.com.au. 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Jane Barnes". x.com. 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b Feliu, Luis (21 July 1978). "Rock Music". The Canberra Times. Vol. 52, no. 15, 643. p. 21. Retrieved 9 May 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Freedom Songs: the role of music in the anti-apartheid struggle - PART A - Anti Apartheid Legacy

- ^ "Winners by Year 1993". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Culnane, Paul (28 May 2001). "The final list: APRA'S Ten best Australian Songs". Australasian Performing Right Association. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ "Chisel come in from the cold". The Age. 30 March 2007.

- ^ Adams, Cameron (28 March 2016). "Cold Chisel honoured at APRAS 2016 with prestigious award for services to Australian music". News Corp Australia. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Boisvert, Eugene (27 March 2021). "Adelaide lane named after Cold Chisel as part of City of Music Laneways Trail". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ "Cold Chisel Lane". Google Maps. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ "Blood Moon by Cold Chisel". Apple Music. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "APRA History". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) | Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society (AMCOS). Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "APRA Announce Star-Studded Song of the Year Top 30". Noise11. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "2016 APRA AWARDS : Date Confirmed". auspOp. April 2016. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Nominees announced for the 2021 APRA Music Awards". APRA AMCOS. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Midnight Oil, Tones And I among big winners at 2021 APRA Music Awards". Industry Observer. 29 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "One of these songs will be the Peer-Voted APRA Song of the Year!". APRA AMCOS. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Winners by Award: Hall of Fame". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Events & Programs". Live Performance Australia. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "2012 Helpmann Awards Nominees & Winners". Helpmann Awards. Australian Entertainment Industry Association (AEIA). Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "About SA Music Hall of Fame". SA Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Inducted Bands". SA Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Countdown to the Awards" (Portable document format (PDF)). Countdown Magazine. Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). March 1987. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

External links

- Cold Chisel

- APRA Award winners

- ARIA Award winners

- ARIA Hall of Fame inductees

- Australian hard rock musical groups

- Australian pub rock musical groups

- Australian musical quintets

- Musical groups established in 1973

- Musical groups disestablished in 1983

- Musical groups reestablished in 2009

- Musical groups from Adelaide

- 1973 establishments in Australia