Okavango Delta: Difference between revisions

→Climate: ft: Frost is sometimes seen over the winter. |

Fixed atrocious grammar and chronological issues in one particular paragraph |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

Since 2005, the protected area has been considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with [[Hwange National Park]].<ref>{{cite book |author=IUCN Cat Specialist Group |year=2006 |title=Conservation Strategy for the Lion ''Panthera leo'' in Eastern and Southern Africa |publisher=IUCN |location=Pretoria, South Africa}}</ref> |

Since 2005, the protected area has been considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with [[Hwange National Park]].<ref>{{cite book |author=IUCN Cat Specialist Group |year=2006 |title=Conservation Strategy for the Lion ''Panthera leo'' in Eastern and Southern Africa |publisher=IUCN |location=Pretoria, South Africa}}</ref> |

||

In 1992, the black rhino was thought to be extinct in the Okavango Delta, while only 19 white rhinos remained.<ref name=BST>{{Cite news |title=Rhino in the Okavango |url=https://www.itravelto.com/rhino-okavango.html |publisher=Botswana Safari Tours |access-date=13 July 2023 |archive-date=13 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230713111925/https://www.itravelto.com/rhino-okavango.html |url-status=live }}</ref> By 1993, all rhinos had been killed in Botswana.<ref name="Independent article">{{cite web |url= https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/campaigns/giantsclub/botswana/botswana-s-imported-rhino-poaching-crisis-b2058230.html|title=Botswana’s imported rhino poaching crisis |publisher=Independent |date=April 14, 2022|access-date=2014-07-19}}.</ref> Hundreds of white and black rhinos were reintroduced by the Botswana Rhino Reintroduction Project founded in 2000.<ref name="Independent article">{{cite web |url= https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/campaigns/giantsclub/botswana/botswana-s-imported-rhino-poaching-crisis-b2058230.html|title=Botswana’s imported rhino poaching crisis |publisher=Independent |date=April 14, 2022|access-date=2014-07-19}}.</ref> From 2010 to 2018, seven rhinos were killed by poachers.<ref name="Bloomberg article">{{cite web |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-23/botswana-moves-rhinos-out-of-okavango-delta-as-poaching-worsens |title=Botswana Moves Rhinos Out of Okavango Delta as Poaching Worsens |work=Bloomberg.com |first=Mbongeni|last=Mguni|date=October 23, 2021|accessdate=2024-07-19}}</ref> By 2019, the rhino population in Botswana had decreased to an estimated 400, with the largest population of roughly 150 living in the northern Okavango Delta.<ref>{{Cite news |title=Poaching, Natural Causes Decimate Botswana's Rhino Population |url=https://www.voanews.com/a/poaching-natural-causes-decimate-botswana-s-rhino-population/6972651.html |publisher=Voa News |access-date=13 July 2023 |archive-date=13 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230713113217/https://www.voanews.com/a/poaching-natural-causes-decimate-botswana-s-rhino-population/6972651.html |url-status=live }}</ref> From 2020 to 2021, 92 rhinos were killed by poachers in the delta region leaving only 40 individuals, prompting the government to move those rhinos out of the Okavango Delta.<ref name=BST/><ref>{{Cite news |title=Botswana Moves Rhinos Out of Okavango Delta as Poaching Worsens |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-23/botswana-moves-rhinos-out-of-okavango-delta-as-poaching-worsens |publisher=Bloomberg |access-date=13 July 2023 |archive-date=22 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221122041225/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-23/botswana-moves-rhinos-out-of-okavango-delta-as-poaching-worsens |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Antílopes lechwes (Kobus leche), vista aérea del delta del Okavango, Botsuana, 2018-08-01, DD 27.jpg|right|thumb|Small gathering of [[lechwe]] antelopes, Okavango Delta]] |

[[File:Antílopes lechwes (Kobus leche), vista aérea del delta del Okavango, Botsuana, 2018-08-01, DD 27.jpg|right|thumb|Small gathering of [[lechwe]] antelopes, Okavango Delta]] |

||

Revision as of 03:17, 20 July 2024

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

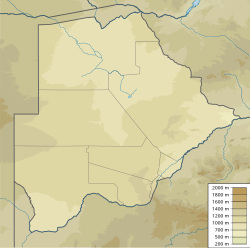

Map of the delta with basin boundary as dashed line | |

| Location | Botswana |

| Criteria | Natural: vii, ix, x |

| Reference | 1432 |

| Inscription | 2014 (38th Session) |

| Area | 2,023,590 ha |

| Buffer zone | 2,286,630 ha |

| Coordinates | 19°24′S 22°54′E / 19.400°S 22.900°E |

| Official name | Okavango Delta System |

| Designated | 12 September 1996 |

| Reference no. | 879[1] |

The Okavango Delta[2] (or Okavango Grassland; formerly spelled "Okovango" or "Okovanggo") in Botswana is a vast inland delta formed where the Okavango River reaches a tectonic trough at an altitude of 930–1,000 m[3] in the central part of the endorheic basin of the Kalahari.

It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site as one of the few interior delta systems that do not flow into a sea or ocean, with a wetland system that is largely intact.[4] All the water reaching the delta is ultimately evaporated and transpired. Each year, about 11 cubic kilometres (2.6 cu mi) of water spreads over the 6,000–15,000 km2 (2,300–5,800 sq mi) area. Some flood waters drain into Lake Ngami.[5] The area was once part of Lake Makgadikgadi, an ancient lake that had mostly dried up by the early Holocene.[6]

The Moremi Game Reserve is on the eastern side of the delta. The delta was named one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa, which were officially declared on 11 February 2013 in Arusha, Tanzania.[7] On 22 June 2014, the Okavango Delta became the 1000th site to be officially inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.[8][4]

Geography

Floods

The Okavango is produced by seasonal flooding. The Okavango River drains the summer (January–February) rainfall from the Angola highlands and the surge flows 1,200 km (750 mi) in around one month. The waters then spread over the 250 by 150 km (155 by 93 mi) area of the delta over the next four months (March–June).

The high temperature of the delta causes rapid transpiration and evaporation, resulting in three cycles of rising and falling water levels[9] that were not fully understood until the early 20th century. The flood peaks between June and August, during Botswana's dry winter months, when the delta swells to three times its permanent size, attracting animals from kilometres around and creating one of Africa’s greatest concentrations of wildlife.

The delta is very flat, with less than 2 m (7 ft) variation in height across its 15,000 km2 (5,800 sq mi),[10] while the water drops about 60 m from Mohembo to Maun.[3][11][12]

Water flow

Lagoons

When the water levels gradually recede, water remains in major canals and river beds, in waterholes and in a number of larger lagoons, which then attract increasing numbers of animals. Photo-safari camps and lodges are found near some of these lagoons. Among the larger lagoons are:

- Dombo Hippo Pool (19°11′58″S 23°38′25″E / 19.19944°S 23.64028°E)

- Gcodikwe Lagoon (19°10′03″S 23°14′24″E / 19.16750°S 23.24000°E)

- Guma Lagoon (18°57′52″S 22°22′41″E / 18.96444°S 22.37806°E)

- Jerejere Lagoon/Hippo Pool (19°05′17″S 23°01′12″E / 19.08806°S 23.02000°E)

- Moanachira Lagoon/Sausage Island (19°03′23″S 23°03′44″E / 19.05639°S 23.06222°E)

- Moanachira Lagoon (19°03′45″S 23°05′24″E / 19.06250°S 23.09000°E)

- Shinde Lagoon (19°06′18″S 23°09′18″E / 19.10500°S 23.15500°E)

- Xakanaxa Lagoon (19°10′48″S 23°23′42″E / 19.18000°S 23.39500°E)

- Xhamu Lagoon (19°10′03″S 23°16′12″E / 19.16750°S 23.27000°E)

- Xhobega Lagoon (19°10′39″S 23°12′36″E / 19.17750°S 23.21000°E)

- Xugana Lagoon (19°04′12″S 23°06′00″E / 19.07000°S 23.10000°E)

- Zibadiania Lagoon (18°34′12″S 23°32′06″E / 18.57000°S 23.53500°E)

Salt islands

The agglomeration of salt around plant roots leads to barren white patches in the centre of many of the thousands of islands, which have become too salty to support plants, aside from the odd salt-resistant palm tree. Trees and grasses grow in the sand around the edges of the islands that have not become too salty yet.

About 70% of the islands began as termite mounds (often Macrotermes spp.), where a tree then takes root on the mound of soil.[13]

Chief's Island

Chief's Island (19°12′S 22°48′E / 19.200°S 22.800°E), the largest island in the delta, was formed by a fault line which uplifted an area over 70 km long (43 mi) and 15 km wide (9.3 mi). Historically, it was reserved as an exclusive hunting area for the chief, but is now a protected area for wildlife. It now provides the core area for much of the resident wildlife when the waters rise.[14]

Climate

The Delta's profuse greenery is not the result of a wet climate; rather, it is an oasis in an arid country. The average annual rainfall is 450 mm (18 in) (approximately one-third that of its Angolan catchment area) and most of it falls between December and March in the form of heavy afternoon thunderstorms.

December to February are hot wet months with daytime temperatures as high as 40 °C (104 °F), warm nights, and humidity levels fluctuating between 50 and 80%. From March to May, the temperature reduces, with a maximum of 30 °C (86 °F) during the day and mild to cool nights. The rains quickly dry up leading into the dry, cool winter months of June to August. Daytime temperatures at this time of year are mild to warm, but the temperature falls considerably after sunset. Nights can be cold in the delta, with temperatures barely above freezing.[15] Frost is sometimes seen over the winter.[16]

The September to November span has the heat and atmospheric pressure build up once more, as the dry season slides into the rainy season. October is the most challenging month for visitors: daytime temperatures often push past 40 °C (104 °F) and the dryness is only occasionally broken by a sudden cloudburst.[17]

Fauna of the delta

The Okavango Delta is both a permanent and seasonal home to a wide variety of wildlife which is now a popular tourist attraction.[18] All of the big five game animals—the lion, leopard, African buffalo, African bush elephant and rhinoceros (both black and white rhinoceros)—are present.[19]

Other species include giraffe, blue wildebeest, plains zebra, hippopotamus,[20] impala, common eland, greater kudu, sable antelope, roan antelope, puku, lechwe, waterbuck, sitatunga, tsessebe, cheetah,[21] African wild dog, spotted hyena, black-backed jackal, caracal, serval, aardvark, aardwolf, bat-eared fox, African savanna hare, honey badger, crested porcupine, common warthog, chacma baboon, vervet monkey and Nile crocodile.[22]

The delta also hosts over 400 bird species, including the helmeted guineafowl, African fish eagle, Pel's fishing owl, Egyptian goose, South African shelduck, African jacana, African skimmer, marabou stork, crested crane, African spoonbill, African darter, southern ground hornbill, wattled crane,[23] lilac-breasted roller, secretary bird, and common ostrich.[24] Prime bird-watching areas are those with a mix of habitats such as the panhandle, the seasonal delta and the parts of the Moremi Game Reserve that are close to the water.[25]

Since 2005, the protected area has been considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with Hwange National Park.[26]

In 1992, the black rhino was thought to be extinct in the Okavango Delta, while only 19 white rhinos remained.[27] By 1993, all rhinos had been killed in Botswana.[28] Hundreds of white and black rhinos were reintroduced by the Botswana Rhino Reintroduction Project founded in 2000.[28] From 2010 to 2018, seven rhinos were killed by poachers.[29] By 2019, the rhino population in Botswana had decreased to an estimated 400, with the largest population of roughly 150 living in the northern Okavango Delta.[30] From 2020 to 2021, 92 rhinos were killed by poachers in the delta region leaving only 40 individuals, prompting the government to move those rhinos out of the Okavango Delta.[27][31]

The most abundant large mammal is the lechwe, with estimates suggesting approximately 88,000 individuals.[32] The lechwe a bit larger than an impala, with elongated hooves and a water-repellent substance on its legs that enable rapid movement through knee-deep water. Lechwe graze on aquatic plants and, like the waterbuck, take to water when threatened by predators. Only the males have horns.[33]

Fish

The Okavango Delta is home to 71 fish species, including the tigerfish, species of tilapia, and various species of catfish. Fish sizes range from the 1.4 m (4.6 ft) African sharptooth catfish to the 3.2 cm (1.3 in) sickle barb. The same species are found in the Zambezi River, indicating an historic link between the two river systems.[34]

Flora of the delta

The Okavango Delta is home to 1068 plants which belong to 134 families and 530 genera.[35] There are five important plant communities in the perennial swamp: Papyrus cyperus in the deeper waters, Miscanthus in the shallowly flooded sites, and Phragmites australis, Typha capensis and Pycreus in between. The swamp-dominant species, which are usually found in the perennial swamp, also extend far into the seasonally inundated area.[17] Papyrus cyperus reeds beds grow best in slow flowing waters of medium depth and are prominent at the channel sides. On the islands and mainlands edges above the flooded grasslands different communities of flora are found. These species are located according to their water preference: for instance Philenoptera violacea requires little water, is found at the highest elevations in the perennial swamps, and is common on drier seasonal swamp islands. Trees restricted to islands within the perennial swamp are a mixture of the palm Hyphaene petersiana and acacias.[35][36]

The plants of the delta play an important role in providing cohesion for the sand. The banks or levees of a river normally have a high mud content, and this combines with the sand in the river’s load to continuously build up the river banks. The river’s load In the delta consists almost entirely of sand, because the clean waters of the Okavango contain little mud. The plants capture the sand, acting as the glue and making up for the lack of mud, and in the process creating further islands on which more plants can take root.

This process is not important in the formation of linear islands. They are long and thin and often curved like a gently meandering river because they are actually the natural banks of old river channels which have become blocked up by plant growth and sand deposition, resulting in the river changing course and the old river levees becoming islands. Due to the flatness of the delta and the large tonnage of sand flowing into it from the Okavango River, the floor of the delta is slowly but constantly rising. Where channels are today, islands will be tomorrow and then new channels may wash away these existing islands.[37]

People

The Okavango Delta peoples consist of five ethnic groups, each with its own ethnic identity and language. They are Hambukushu (also known as Mbukushu, Bukushu, Bukusu, Mabukuschu, Ghuva, Haghuva), Dceriku (Dxeriku, Diriku, Gciriku, Gceriku, Giriku, Niriku), Wayeyi (Bayei, Bayeyi, Yei), Bugakhwe (Kxoe, Khwe, Kwengo, Barakwena, G|anda) and ǁanikhwe (Gxanekwe, ǁtanekwe, River Bushmen, Swamp Bushmen, Gǁani, ǁani, Xanekwe). The Hambukushu, Dceriku, and Wayeyi have traditionally engaged in mixed economies of millet/sorghum agriculture, fishing, hunting, the collection of wild plant foods, and pastoralism.

The Bugakhwe and ǁanikwhe are Bushmen, who have traditionally practised fishing, hunting, and the collection of wild plant foods; Bugakhwe used both forest and riverine resources, while the ǁanikhwe mostly focused on riverine resources. The Hambukushu, Dceriku, and Bugakhwe are present along the Okavango River in Angola and in the Caprivi Strip of Namibia, and small numbers of Hambukushu and Bugakhwe are in Zambia, as well. Within the Okavango Delta, over the past 150 years or so, Hambukushu, Dceriku, and Bugakhwe have inhabited the panhandle and the Magwegqana in the northeastern delta. ǁanikhwe have inhabited the panhandle and the area along the Boro River through the delta, as well as the area along the Boteti River.

The Wayeyi[38] have inhabited the area around Seronga as well as the southern delta around Maun, and a few Wayeyi[39] live in their putative ancestral home in the Caprivi Strip. Within the past 20 years many people from all over the Okavango have migrated to Maun, the late 1960s and early 1970s over 4,000 Hambukushu refugees from Angola were settled in the area around Etsha in the western Panhandle.

The Okavango Delta has been under the political control of the Batawana (a Tswana nation) since the late 18th century.[40] Led by the house of Mathiba I, the leader of a Bangwato offshoot, the Batawana established complete control over the delta in the 1850s as the regional ivory trade exploded.[41] Most Batawana, however, have traditionally lived on the edges of the delta, due to the threat that the tsetse fly poses to their cattle. During a hiatus of some 40 years, the tsetse fly retreated and most Batawana lived in the swamps from 1896 through the late 1930s. Since then, the edge of the delta has become increasingly crowded with its growing human and livestock populations.

Molapos (water streams)

After the flooding season, the waters in the lower parts of the delta, near the base, recede, leaving moisture behind in the soil. This residual moisture is used for planting fodder and other crops that can thrive on it. This land is locally known as molapo.

During 1974 to 1978, the floods were more intensive than normal and flood recession cropping was not possible, so severe food and fodder shortages occurred. In response, the Molapo Development Project was initiated. It protected the molapo areas with bunds to control the flooding and prevent severe flooding. The bunds are provided with sluice gates so the stored water can be released and flood recession cropping can start.[42]

Possible threats

One possible threat is oil exploration by Canadian company ReconAfrica. Initial exploration in April 2021 revealed oil deposits in sedimentary rock.[43] Environmentalists are concerned that the project will have a negative ecological impact and that some of the main bodies of water could be threatened.[44][45][46] ReconAfrica has stated, "There will be no damage to the ecosystem from the planned activities."[47][48]

The Namibian government has presented plans to build a hydropower station in the Zambezi Region, which would regulate the Okavango's flow to some extent. While proponents argue that the effect would be minimal, environmentalists argue that this project could destroy most of the rich animal and plant life in the delta.[49] Other threats include local human encroachment and regional extraction of water in both Angola and Namibia.[50][51]

South African filmmaker and conservationist Rick Lomba warned in the 1980s of the threat of cattle invasion to the area. His documentary The End of Eden portrayed his lobbying on behalf of the delta.

The Okavango catchment is projected to experience decreasing annual rainfall as well as increasing temperatures as a result of global warming.[52] The effects of global warming are likely to result in reductions in the extent of floodplains in the Okavango Delta, which will have significant impacts on water availability as well as livestock rearing and agricultural activities in the region.[53]

See also

References

- ^ "Okavango Delta System". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Ross, Karen (1987). Okavango, jewel of the Kalahari. London: BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-20545-8. OCLC 17978845.

- ^ a b "Ramsar Information Sheet" (PDF). 20 November 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

The total drop in altitude between Mohembo and Maun, a distance of440 km, is only 62 metres, giving a gradient of approximately 1:7,000 only

- ^ a b Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Twenty six new properties added to World Heritage List at Doha meeting". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Keen, Cecil (1997). "Okavango Delta". Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ McCarthy, T. S. (1993). "The great inland deltas of Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 17 (3): 275–291. Bibcode:1993JAfES..17..275M. doi:10.1016/0899-5362(93)90073-Y.

- ^ "Seven Natural Wonders of Africa – Seven Natural Wonders". sevennaturalwonders.org. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "World Heritage List reaches 1000 sites with inscription of Okavango Delta in Botswana". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ C. N. Kurugundla; N. M. Moleele; K.Dikgola. "Flow Partitioning Within the Okavango Delta –A Pre-requisite for Environmental Flow Assessment for Human Livelihoods and Sustainable Biodiversity Management" (PDF). University of Botswana. pp. 8–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Okavango Delta". Archived from the original on 19 July 2009.

- ^ Wehberg, Jan (31 December 2013). "Okavango Basin - Physicogeographical setting". Biodiversity and Ecology. 5: 11. doi:10.7809/b-e.00236.

- ^ Gumbricht, T. (1 September 2001). "The topography of the Okavango Delta, Botswana, and its tectonic and sedimentological implications". South African Journal of Geology. 104 (3): 243–264. doi:10.2113/1040243.

- ^ Dunford, Chris. "Nature explored:Moremi/Okavango Delta in August". Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Okavango delta Botswana | Mokoro and boating safaris". Okavango Safaris. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Botswana climate: average weather, temperature, precipitation, best time". www.climatestotravel.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ https://www.naturalhistoryfilmunit.com/post/a-year-in-the-okavango-delta A Year in the Okavango Delta

- ^ a b UNEP-WCMC (22 May 2017). "OKAVANGO DELTA". World Heritage Datasheet. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Bradley, John H. (October 2009). "Gliding in a Mokoro Through the Okavango Delta, Botswana". Cape Town to Cairo Website. CapeTowntoCairo.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Galpine, N. J. (2006). "Boma management of black and white rhinoceros at Mombo, Okavango Delta—Some lessons" (PDF). Ecological Journal. 7: 55−61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ McCarthy, T. S.; Ellery, W. N.; Bloem, A. (1998). "Some observations on the geomorphological impact of hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius L.) in the Okavango Delta, Botswana". African Journal of Ecology. 36 (1): 44−56. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2028.1998.89-89089.x.

- ^ Klein, R. (2007). "Status report for the cheetah in Botswana" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 1: 13−21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Wallace, K. M.; Leslie, A. J. (2008). "Diet of the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) in the Okavango Delta, Botswana". Journal of Herpetology. 42 (2): 361−368. doi:10.1670/07-1071.1. S2CID 46987629.

- ^ Alonso, L. E.; Nordin, L.-A., eds. (2003). A rapid biological assessment of the aquatic ecosystems of the Okavango Delta, Botswana: High Water Survey. RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment. Vol. 27. Washington, DC: Conservation International. ISBN 1-881173-70-4.

- ^ Mbaiwa, J. E.; Mbaiwa, O. I. (2006). "The effects of veterinary fences on wildlife populations in Okavango Delta, Botswana". International Journal of Wilderness. 12 (3): 17−41. hdl:10311/28.

- ^ Adrian, Bailey (1998). OKAVANGO; Africa's Wetland Wilderness. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Publishers (Pty) Ltd. pp. 66–73. ISBN 1868720411.

- ^ IUCN Cat Specialist Group (2006). Conservation Strategy for the Lion Panthera leo in Eastern and Southern Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: IUCN.

- ^ a b "Rhino in the Okavango". Botswana Safari Tours. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Botswana's imported rhino poaching crisis". Independent. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2014..

- ^ Mguni, Mbongeni (23 October 2021). "Botswana Moves Rhinos Out of Okavango Delta as Poaching Worsens". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Poaching, Natural Causes Decimate Botswana's Rhino Population". Voa News. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Botswana Moves Rhinos Out of Okavango Delta as Poaching Worsens". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Chase, M.; Schlossberg, S.; Landen, K.; Sutcliffe, R.; Seonyatseng, E.; Keitsile, A. & Flyman, M. (2018). Dry Season Aerial Survey of Elephants and Wildlife in Northern Botswana (Report). Botswana: Elephants Without Borders, the Department of Wildlife and National Parks and the Great Elephant Census.

- ^ "Lechwe | mammal". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Ramberg, Lars (2006). "Species diversity of the Okavango Delta,Botswana". Aquatic Sciences. 3: 316 – via Researchgate.

- ^ Toerien, D. K. (15 August 1976). "Geologie van die Tsitsikamakusstrook". Koedoe. 19 (1). doi:10.4102/koedoe.v19i1.1179. ISSN 2071-0771.

- ^ "Okavango Delta – Part 2 -". blog.africabespoke.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Wayeyi". Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Alexander Colin; N’teta, Doreen (March 1980). "The National Museum and Art Gallery, Gaborone, Botswana". Museum International. 32 (1–2): 61–66. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.1980.tb01909.x. ISSN 1350-0775. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Segolodi, Moanaphuti (1940). "Ditso Tsa Batawana". Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ Morton, Barry (1997). "The Hunting Trade and the Reconstruction of Northern Tswana Societies after the Difaqane, 1838–1880". South African Historical Journal. 36: 220–239. doi:10.1080/02582479708671276.

- ^

Kortenhorst, L. F.; et al. (1986). Development of flood-recession cropping in the molapo's of the Okavango Delta, Botswana (PDF). Wageningen, The Netherlands: International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement. pp. 8–19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

Kortenhorst, L. F.; et al. (1986). Development of flood-recession cropping in the molapo's of the Okavango Delta, Botswana (PDF). Wageningen, The Netherlands: International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement. pp. 8–19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017. {{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ltd, Reconnaissance Energy Africa. "ReconAfrica's First of Three Wells Confirms a Working Petroleum System in the Kavango Basin, Namibia". www.newswire.ca. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "A Big Oil Project in Africa Threatens Fragile Okavango Region". Yale E360. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "Growing concern over Okavango oil exploration as community alleges shutout". Mongabay Environmental News. 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Test drilling for oil in Namibia's Okavango region poses toxic risk". Animals. 12 March 2021. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: ReconAfrica Initial Drilling Project". reconafrica.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Wilson-Spath, Andreas (15 December 2020). "OP-ED: Paradise is closing down: The ghastly spectre of oil drilling and fracking in fragile Okavango Delta". Daily Maverick. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "FindArticles.com - CBSi". findarticles.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Threats - Okavango Delta". www.okavangodelta.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Chinese-Angolan project in Angola harvests over 1,200 tons of rice". 11 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ ASSAR (2019). What global warming of 1.5°C and higher means for Botswana (PDF). Adaptation at Scale in Semi Arid Regions (ASSAR). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Murray-Hudson, M.; Wolski, P.; Ringrose, S. (2006). "Scenarios of the impact of local and upstream changes in climate and water use on hydro-ecology in the Okavango Delta, Botswana". Journal of Hydrology. Water Resources in Regional Development: The Okavango River. 331 (1): 73–84. Bibcode:2006JHyd..331...73M. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.04.041.

Further reading

- Allison, P. (2007). Whatever You Do, Don't Run: True Tales Of A Botswana Safari Guide. Globe Pequot. ISBN 9780762745654.

- Bock, J. (2002). "Learning, Life History, and Productivity: Children's lives in the Okavango Delta of Botswana". Human Nature. 13 (2): 161–198. doi:10.1007/s12110-002-1007-4. PMID 26192757. S2CID 28985956.

External links

- Conservation International

- Okavango Delta concession areas

- Flow : information for Okavango Delta planning is the weblog of the Library of the Harry Oppenheimer Okavango Research Institute

- The Ngami Times is Ngamiland's weekly newspaper

- Official Botswana Government site on Moremi Game Reserve, inside the Okavango Delta

- Wild Entrust International

- Seven Natural Wonders of Africa

- Discovery Channel - Kalahari Flood

- Flood-recession cropping in the molapos of the Okavango Delta

- Okavango Research Institute

- Current Okavango water levels, weather data and satellite images

- 1986 Documentary The End of Eden by Rick Lomba

- Southern African Game Reserves - Okavango Delta