Westminster Abbey: Difference between revisions

→Architecture: Added photograph: Tympanum, Westminster Abbey, England, July 20, 2023.jpg |

m →Architecture: Added Tympanum (architecture) Wiki link to Tympanum, Westminster Abbey, England, July 20, 2023.jpg photograph |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

| caption1 = North door of the abbey, with rose window and flying buttresses above |

| caption1 = North door of the abbey, with rose window and flying buttresses above |

||

| image2 = Tympanum, Westminster Abbey, England, July 20, 2023.jpg |

| image2 = Tympanum, Westminster Abbey, England, July 20, 2023.jpg |

||

| caption2 = Tympanum above the North Entrance |

| caption2 = [[Tympanum (architecture)|Tympanum]] above the North Entrance |

||

| image3 = Lift tower for Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries.jpg |

| image3 = Lift tower for Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries.jpg |

||

| caption3 = The Weston Tower, tucked behind a flying buttress |

| caption3 = The Weston Tower, tucked behind a flying buttress |

||

Revision as of 22:40, 25 August 2024

| Westminster Abbey | |

|---|---|

| Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster | |

Westminster Abbey's western facade | |

| Location | Dean's Yard, London, SW1 |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Catholic Church |

| Churchmanship | Anglo-Catholic |

| Website | westminster-abbey |

| History | |

| Status | Collegiate church |

| Founded | c. 959 |

| Consecrated | 28 December 1065, 13 October 1269 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | UNESCO World Heritage Site |

| Designated | 1987 |

| Specifications | |

| Nave width | 85 feet (26 m)[1] |

| Height | 101 feet (31 m)[1] |

| Floor area | 32,000 square feet (3,000 m2)[1] |

| Number of towers | 2 |

| Tower height | 225 feet (69 m)[1] |

| Materials | Reigate stone; Portland stone; Purbeck marble |

| Bells | 10 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Extra-diocesan (royal peculiar) |

| Clergy | |

| Dean | David Hoyle |

| Canon(s) | see Dean and Chapter |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Andrew Nethsingha (Organist and Master of the Choristers) |

| Organist(s) | Peter Holder (sub-organist) Matthew Jorysz (assistant) |

| Organ scholar | Dewi Rees |

| Coordinates | 51°29′58″N 00°07′39″W / 51.49944°N 0.12750°W |

| Founded | c. 959 |

| Official name | Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and Saint Margaret's Church |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 426 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Westminster Abbey (The Collegiate Church of St Peter) |

| Designated | 24 February 1958 |

| Reference no. | 1291494[2] |

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British monarchs and a burial site for 18 English, Scottish, and British monarchs. At least 16 royal weddings have taken place at the abbey since 1100.

Although the origins of the church are obscure, an abbey housing Benedictine monks was on the site by the mid-10th century. The church got its first large building from the 1040s, commissioned by King Edward the Confessor, who is buried inside. Construction of the present church began in 1245 on the orders of Henry III. The monastery was dissolved in 1559, and the church was made a royal peculiar – a Church of England church, accountable directly to the sovereign – by Elizabeth I. The abbey, the Palace of Westminster and St. Margaret's Church became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987 because of their historic and symbolic significance.

The church's Gothic architecture is chiefly inspired by 13th-century French and English styles, although some sections of the church have earlier Romanesque styles or later Baroque and modern styles. The Henry VII Chapel, at the east end of the church, is a typical example of Perpendicular Gothic architecture; antiquarian John Leland called it orbis miraculum ("the wonder of the world").

The abbey is the burial site of more than 3,300 people, many prominent in British history: monarchs, prime ministers, poets laureate, actors, musicians, scientists, military leaders, and the Unknown Warrior. Due to the fame of the figures buried there, artist William Morris described the abbey as a "National Valhalla".

History

Historians agree that there was a monastery dedicated to Saint Peter on the site prior to the 11th century, though its exact origin is somewhat obscure. One legend claims that it was founded by the Saxon king Sæberht of Essex, and another claims that its founder was the fictional 2nd-century British king Lucius.[3] One tradition claims that a young fisherman on the River Thames had a vision of Saint Peter near the site. This seems to have been quoted as the origin of the salmon that Thames fishermen offered to the abbey, a custom still observed annually by the Fishmongers' Company.[4]

The origins of the abbey are generally thought to date to about 959, when Saint Dunstan and King Edgar installed a community of Benedictine monks on the site.[5] At that time, the location was an island in the middle of the River Thames called Thorn Ey.[6] This building has not survived, but archaeologists have found some pottery and foundations from this period on the abbey site.[7]

Edward the Confessor's abbey

Between 1042 and 1052, Edward the Confessor began rebuilding Saint Peter's Abbey to provide himself with a royal burial church. It was built in the Romanesque style and was the first church in England built on a cruciform floorplan.[8] The master stonemason for the project was Leofsi Duddason,[9] with Godwin and Wendelburh Gretsyd (meaning "fat purse") as patrons, and Teinfrith as "churchwright", probably meaning someone who worked on the carpentry and roofing.[10] Endowments from Edward supported a community that increased from a dozen monks during Dunstan's time, to as many as 80.[11] The building was completed around 1060 and was consecrated on 28 December 1065, about a week before Edward's death on 5 January 1066.[12] A week later, he was buried in the church; nine years later, his wife Edith was buried alongside him.[13] His successor, Harold Godwinson, was probably crowned here, although the first documented coronation is that of William the Conqueror later that year.[14]

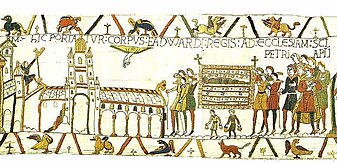

The only extant depiction of Edward's abbey is in the Bayeux Tapestry. The foundations still survive under the present church, and above ground, some of the lower parts of the monastic dormitory survive in the undercroft, including a door said to come from the previous Saxon abbey. It was a little smaller than the current church, with a central tower.[15]

In 1103, thirty-seven years after his death, Edward's tomb was re-opened by Abbot Gilbert Crispin and Henry I, who discovered that his body was still in perfect condition. This was considered proof of his saintliness, and he was canonised in 1161. Two years later he was moved to a new shrine, during which time his ring was removed and placed in the abbey's collection.[16]

The abbey became more closely associated with royalty from the second half of the 12th century, as kings increasingly used the nearby Palace of Westminster as the seat of their governments.[17] In 1222, the abbey was officially granted exemption from the Bishop of London's jurisdiction, making it answerable only to the head of the Church itself. By this time, the abbey owned a large swath of land around it, from modern-day Oxford Street to the Thames, plus entire parishes in the City of London, such as St. Alban Wood Street and St. Magnus the Martyr, as well as several wharfs.[18]

Outside London, the abbey owned estates across southeast England, including in Middlesex, Hertfordshire, Essex, Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.[19] The abbot was also the lord of the manor in Westminster, as a town of two to three thousand people grew around the abbey.[20] As a consumer and employer on a grand scale, the abbey helped fuel the town's economy, and relations with the town remained unusually cordial, but no enfranchising charter was issued during the Middle Ages.[21]

Henry III's rebuilding

Westminster Abbey continued to be used as a coronation site, but after Edward the Confessor, no monarchs were buried there until Henry III began to rebuild it in the Gothic style. Henry III wanted it built as a shrine to venerate Edward, to match great French churches such as Rheims Cathedral and Sainte-Chapelle,[22] and as a burial place for himself and his family.[23] Construction began on 6 July 1245 under Henry's master mason, Henry of Reynes.[9] The first building stage included the entire eastern end, the transepts, and the easternmost bay of the nave. The Lady chapel, built from around 1220 at the extreme eastern end, was incorporated into the chevet of the new building.

Part of the new building included a rich shrine and chapel to Edward the Confessor, of which the base only still stands. The golden shrine with its jewelled figures no longer exists.[24] 4,000 marks (about £5,800) for this work came from the estate of David of Oxford, the husband of Licoricia of Winchester, and a further £2,500 came from a forced contribution from Licoricia herself, by far the biggest single donation at that time. [25]

Around 1253, Henry of Reynes was replaced by John of Gloucester, who was replaced by Robert of Beverley around 1260.[26] During the summer, there were up to 400 workers on the site at a time,[27] including stonecutters, marblers, stone-layers, carpenters, painters and their assistants, marble polishers, smiths, glaziers, plumbers, and general labourers.[28] From 1257, Henry III held assemblies of local representatives in Westminster Abbey's chapter house; these assemblies were a precursor to the House of Commons. Henry III also commissioned the Cosmati pavement in front of the High Altar.[29] Further work produced an additional five bays for the nave, bringing it to one bay west of the choir. Here, construction stopped in about 1269. By 1261, Henry had spent £29,345 19s 8d on the abbey, and the final sum may have been near £50,000.[30] A consecration ceremony was held on 13 October 1269, during which the remains of Edward the Confessor were moved to their present location at the shrine behind the main altar.[31] After Henry's death and burial in the abbey in 1272, construction did not resume and Edward the Confessor's old Romanesque nave remained attached to the new building for over a century.[26]

In 1296, Edward I captured the Scottish coronation stone, the Stone of Scone. He had a Coronation Chair made to hold it, which he entrusted to the abbot at Westminster Abbey.[32] In 1303, the small crypt underneath the chapter house was broken into and a great deal of the king's treasure was stolen. It was thought that the thieves must have been helped by the abbey monks, fifty of whom were subsequently imprisoned in the Tower of London.[33]

Completion of the Gothic church

From 1376, Abbot Nicholas Litlyngton and Richard II donated large sums to finish the church. The remainder of the old nave was pulled down and rebuilding commenced, with his mason Henry Yevele closely following the original design even though it was now more than 100 years out of date.[34][35] During the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, Richard prayed at Edward the Confessor's shrine for "divine aid when human counsel was altogether wanting" before meeting the rebels at Smithfield. In the modern day, the abbey holds Richard's full-length portrait, the earliest of an English king, on display near the west door.[36]

Building work was not fully complete for many years. Henry V, disappointed with the abbey's unfinished state, gave extra funds towards the rebuilding. In his will, he left instructions for a chantry chapel to be built over his tomb; the chapel can be seen from ground level.[37] Between 1470 and 1471, because of fallout from the Wars of the Roses, Elizabeth Woodville, the wife of Edward IV, took sanctuary at Westminster Abbey while her husband was deposed, and gave birth to Edward V in the abbot's house.[38] In 1495, building work finally reached the end of the nave, finishing with the west window.[39]

Under Henry VII, the 13th-century Lady chapel was demolished and rebuilt in a Perpendicular Gothic style; it is known as the Henry VII Chapel. Work began in 1503 and the main structure was completed by 1509, although decorative work continued for several years afterwards.[39] Henry's original reason for building such a grand chapel was to have a place suitable for the burial of another saint alongside the Confessor, as he planned on having Henry VI canonised. The Pope asked Henry VII for a large sum of money to proclaim Henry VI a saint; Henry VII was unwilling to pay the sum, and so instead he is buried in the centre of the chapel with his wife, Elizabeth of York,[40] rather than a large raised shrine like the Confessor.

A view of the abbey dated 1532 shows a lantern tower above the crossing,[41] but this is not shown in any later depiction. It is unlikely that the loss of this feature was caused by any catastrophic event: structural failure seems more likely.[42] Other sources maintain that a lantern tower was never built. The current squat pyramid dates from the 18th century; the painted wooden ceiling below it was installed during repairs to World War II bomb damage.[43]

In the early 16th century, a project began under Abbot John Islip to add two towers to the western end of the church. These had been partially built up to roof level when building work stopped due to uncertainty caused by the English Reformation.[44]

Dissolution and Reformation

In the 1530s, Henry VIII broke away from the authority of the Catholic Church in Rome and seized control of England's monasteries, including Westminster Abbey, beginning the English Reformation.[45] In 1535, when the king's officers assessed the abbey's funds, their annual income was £3,000.[46] Henry's agents removed many relics, saints' images, and treasures from the abbey. The golden feretory that housed the coffin of Edward the Confessor was melted down, and monks hid his bones to save them from destruction.[47] The monastery was dissolved and the building became the cathedral for the newly created Diocese of Westminster.[48] The abbot, William Benson, became dean of the cathedral, while the prior and five of the monks were among the twelve newly created canons.[49]

The Westminster diocese was dissolved in 1550, but the abbey was recognised (in 1552, retroactively to 1550) as a second cathedral of the Diocese of London until 1556.[48] Money meant for the abbey, which is dedicated to Saint Peter, was diverted to the treasury of St. Paul's Cathedral; this led to an association with the already-old saying "robbing Peter to pay Paul".[50]

The abbey saw the return of Benedictine monks under the Catholic Mary I, but they were again ejected under Elizabeth I in 1559.[51] In 1560, Elizabeth re-established Westminster as a "royal peculiar" – a church of the Church of England responsible directly to the sovereign, rather than to a diocesan bishop – and made it the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter, a non-cathedral church with an attached chapter of canons, headed by a dean.[31][52] From that date onwards, the building was simply a church, though it was still called an abbey. Elizabeth also re-founded Westminster School, providing for 40 students (the King's (or Queen's) Scholars) and their schoolmasters. The King's Scholars have the duty of shouting Vivat Rex or Vivat Regina ("Long live the King/Queen") during the coronation of a new monarch. In the modern day, the dean of Westminster Abbey remains the chair of the school governors.[31]

In the early 17th century, the abbey hosted two of the six companies of churchmen who produced the King James Version of the Bible. They used the Jerusalem Chamber in the abbey for their meetings. The First Company was headed by the dean of the abbey, Lancelot Andrewes.[53]

In 1642, the English Civil War broke out between Charles I and his own parliament. The Dean and Chapter fled the abbey at the outbreak of war, and were replaced by priests loyal to Parliament.[54] The abbey itself suffered damage during the war; altars, stained glass, the organ, and the Crown Jewels were damaged or destroyed.[55] Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell was given an elaborate funeral there in 1658, only for a body thought to be Cromwell's to be disinterred in January 1661 and posthumously hanged from a gibbet at Tyburn.[56] In 1669, the abbey was visited by the diarist Samuel Pepys, who saw the body of the 15th-century queen Catherine de Valois. She had been buried in the 13th-century Lady chapel in 1437, but was exhumed during building work for the Henry VII Chapel and not reburied in the intervening 150 years. Pepys leaned into the coffin and kissed her on the mouth, writing "This was my birthday, thirty-six years old and I did first kiss a queen." She has since been re-interred close to her husband, Henry V.[57] In 1685, during preparations for the coronation of James II, a workman accidentally put a scaffolding pole through the coffin of Edward the Confessor. A chorister, Charles Taylour, pulled a cross on a chain out of the coffin and gave it to the king, who then gave it to the Pope. Its whereabouts are unknown.[58]

18th and 19th centuries

At the end of the 17th century, the architect Christopher Wren was appointed the abbey's first Surveyor of the Fabric. He began a project to restore the exterior of the church,[44] which was continued by his successor, William Dickinson.[55] After over two hundred years, the abbey's two western towers were built in the 1740s in a Gothic–Baroque style by Nicholas Hawksmoor and John James.[44][2]

On 11 November 1760, the funeral of George II was held at the abbey, and the king was interred next to his late wife, Caroline of Ansbach. He left instructions for the sides of his and his wife's coffins to be removed so that their remains could mingle.[59] He was the last monarch to be buried in the abbey.[60] Around the same time, the tomb of Richard II developed a hole through which visitors could put their hands. Several of his bones went missing, including a jawbone which was taken by a boy from Westminster School and kept by his family until 1906, when it was returned to the abbey.[61]

In the 1830s, the screen dividing the nave from the choir, which had been designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, was replaced by one designed by Edward Blore. The screen contains the monuments to the scientist Isaac Newton and the military general James Stanhope.[62] Further rebuilding and restoration occurred in the 19th century under the architect George Gilbert Scott, who rebuilt sections of the chapter house and north porches, and designed a new altar and reredos for the crossing. His successor, J. L. Pearson, finished the work on the north porches and also reconstructed the northern rose window.[63]

20th century

The abbey saw "Prayers For Prisoners" suffragette protests in 1913 and 1914. Protesters attended services and interrupted proceedings by chanting "God Save Mrs. Pankhurst" and praying for suffragette prisoners. In one protest, a woman chained herself to her chair during a sermon by the Archbishop of Canterbury.[2] On 11 June 1914, a bomb planted by suffragettes of the Women's Social and Political Union exploded inside the abbey.[64] No serious injuries were reported,[65] but the bomb blew off a corner of the Coronation Chair.[64] It also caused the Stone of Scone to break in half, although this was not discovered until 1950 when four Scottish nationalists broke into the church to steal the stone and return it to Scotland.[64]

In preparation for bombing raids during World War II, the Coronation Chair and many of the abbey's records were moved out of the city, and the Stone of Scone was buried.[66] In 1941, on the night of 10 May and the early morning of 11 May, the Westminster Abbey precincts and roof were hit by incendiary bombs.[67] Although the Auxiliary Fire Service and the abbey's own fire-watchers were able to stop the fire spreading to the whole of the church, the deanery and three residences of abbey clergy and staff were badly damaged, and the lantern tower above the crossing collapsed, leaving the abbey open to the sky.[68] The cost of the damage was estimated at £135,000.[69] Some damage can still be seen in the RAF Chapel, where a small hole in the wall was created by a bomb that fell outside the chapel.[70] No one was killed, and the abbey continued to hold services throughout the war. When hostilities ceased, evacuated objects were returned to the abbey, 60,000 sandbags were moved out, and a new permanent roof was built over the crossing.[66] Two different designs for a narthex (entrance hall) for the west front were produced by architects Edwin Lutyens and Edward Maufe during World War II, but neither was built.[71][72]

Because of its outstanding universal value, the abbey was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, together with the nearby Palace of Westminster and St. Margaret's Church.[73]

In 1997, the abbey, which was then receiving approximately 1.75 million visitors each year, began charging admission fees to visitors at the door[74] (although a fee for entering the eastern half of the church had existed prior to 1600).[75]

21st century

In June 2009, the first major building work in 250 years was proposed.[76] A corona – a crown-like architectural feature – was suggested to be built around the lantern over the central crossing, replacing an existing pyramidal structure dating from the 1950s.[77] This was part of a wider £23-million development of the abbey completed in 2013.[76] On 4 August 2010, the Dean and Chapter announced that, "after a considerable amount of preliminary and exploratory work", efforts toward the construction of a corona would not be continued.[78]

The Cosmati pavement underwent a major cleaning and restoration programme for two years, beginning in 2008.[79] On 17 September 2010, Pope Benedict XVI became the first pope to set foot in the abbey when he participated in a service of evening prayer with archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams.[80] On 29 April 2011, the abbey hosted the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton.[81]

In 2018, the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries were opened. Located in the medieval triforium, high up around the sanctuary, they are areas for displaying the abbey's treasures. A new Gothic access tower with a lift was designed by the abbey architect and Surveyor of the Fabric, Ptolemy Dean.[82][83]

In 2020, a 13th-century sacristy was uncovered in the grounds of the abbey as part of an archaeological excavation. The sacristy was used by the monks of the abbey to store objects used in Mass, such as vestments and chalices. Also on the site were hundreds of buried bodies, mostly of abbey monks.[84]

On 10 March 2021, a vaccination centre opened in Poets' Corner to administer doses of COVID-19 vaccines.[85]

Architecture

The building is chiefly built in a Geometric Gothic style, using Reigate stone for facings. The church has an eleven-bay nave with aisles, transepts, and a chancel with ambulatory and radiating chapels. The building is supported with two tiers of flying buttresses. The western end of the nave and the west front were designed by Henry Yevele in a Perpendicular Gothic style. The Henry VII Chapel was built in a late Perpendicular style in Huddlestone stone, probably by Robert and William Vertue. The west towers were designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor and blend the Gothic style of the abbey with the Baroque style fashionable during his lifetime.[2]

The modern Westminster Abbey is largely based on French Gothic styles, especially those found at Reims Cathedral, rather than the contemporaneous English Gothic styles. For example, the English Gothic style favours large and elaborate towers, while Westminster Abbey did not have any towers until the 18th century. It is also more similar to French churches than English ones in terms of its ratio of height to width: Westminster Abbey has the highest nave of any Gothic church in England, and the nave is much narrower than any medieval English church of a similar height. Instead of a short, square, eastern end (as was the English fashion), Westminster Abbey has a long, rounded apse, and it also has chapels radiating from the ambulatory, which is typical of a French Gothic style. However, there are also distinctively English elements, such as the use of materials of contrasting colours, as with the Purbeck marble and white stone in the crossing.[86]

The northern entrance has three porches, with the central one featuring an elaborately-carved tympanum,[87] leading it to acquire the nickname "Solomon's porch" as a reference to the legendary temple in Jerusalem.[88]

The abbey retains its 13th- and 14th-century cloisters, which would have been one of the busiest parts of the church when it was part of a monastery. The west cloister was used for the teaching of novice monks, the north for private study. The south cloister led to the refectory, and the east to the chapter house and dormitory.[89] In the southwest corner of the cloisters is a cellarium formerly used by the monks to store food and wine; in modern times, it is the abbey café.[90] The north cloister and northern end of the east cloister, closest to the church, are the oldest; they date to c. 1250, whereas the rest are from 1352 to 1366.[91] The abbey also contains a Little Cloister, on the site of the monks' infirmary. The Little Cloister dates from the end of the 17th century and contains a small garden with a fountain in the centre.[92] A passageway from the Little Cloister leads to College Garden, which has been in continuous use for 900 years, beginning as the medicine garden for the monks of the abbey and now overlooked by canons' houses and the dormitory for Westminster School.[93]

The newest part of the abbey is the Weston Tower, finished in 2018 and designed by Ptolemy Dean. It sits between the chapter house and the Henry VII Chapel, and contains a lift shaft and spiral staircase to allow public access to the triforium, which contains the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries.[94] The tower has a star-shaped floorplan and leaded windows with an elaborate crown rooftop. The lift shaft inside is faced with 16 kinds of stone from the abbey's history, including Purbeck marble, Reigate stone, and Portland stone. The project took five years and cost £22.9 million. The galleries were designed by McInnes Usher McKnight.[83]

Interior

The church's interior has Purbeck marble piers and shafting. The roof vaulting is quadripartite, with ridge ribs and bosses[2] and, at 102 feet (31 m), it is one of Britain's highest church vaults.[8] To accommodate as many guests as possible during coronations, the transepts were designed to be unusually long[95] and the choir was placed east (rather than west) of the crossing; this is also seen in Rheims Cathedral.[96] The 13th-century interior would have been painted in bright colours and gilded, although the piers would have been left unpainted.[97]

Although the nave was built over the course of centuries from the east to the west end, generations of builders stuck to the original design and it has a unified style. Markers of the long gap in building between 1269 and 1376 are relatively minor, but can be seen at the fifth bay from the crossing. The spandrels above the arches are towards the earlier east end are decorated with diaper-work, and are plain towards the (later) west end. The lancet windows on the earlier side have a foiled circle, and have an unencircled quatrefoil on the later side; the shields on the aisle walls are carved on the earlier side, and painted on the later side.[98][99] Above the crossing, in the centre of the church, is a roof lantern which was destroyed by a bomb in 1941 and restored by architect Stephen Dykes Bower in 1958.[100] In the choir aisles, shields of donors to the 13th- and 14th-century rebuilding are carved and painted in the spandrels of the arcade.[101] At the eastern end of the nave is a large screen separating the nave from the choir, made of 13th-century stone, reworked by Edward Blore in 1834, and with paintwork and gilding by Bower in the 1960s.[98]

Behind the main altar is the shrine and tomb of Edward the Confessor. Saints' shrines were once common in English medieval churches, but most were destroyed during the English Reformation and Edward is the only major English saint whose body still occupies his shrine.[102] Arranged around him in a horseshoe shape are a series of tombs of medieval kings and their queens: Henry III, Eleanor of Castile, Edward I, Philippa of Hainault, Edward III, Anne of Bohemia, and Richard II. Henry V is in the centre of the horseshoe, at the eastern end.[103] Henry III's tomb was originally covered with pieces of coloured glass and stone, since picked off by generations of tourists.[104] Above Henry V's tomb, at mezzanine level over the ambulatory, is a chantry chapel built by mason John Thirske and decorated with many sculpted figures (including Henry V riding a horse and being crowned in the abbey).[105] At the western end, the shrine is separated from the main church by a stone reredos which makes it a semi-private space.[103] The reredos depicts episodes from Edward's life, including his birth and the building of the abbey.[106] The shrine is closed to the public, except for special events.[107]

The abbey includes side chapels radiating from the ambulatory. Many were originally included in the 13th-century rebuilding as altars dedicated to individual saints, and many of the chapels still bear saints' names (such as St. Nicholas and St. Paul). Saints' cults were no longer orthodox after the English Reformation, and the chapels were repurposed as places for extra burials and monuments.[108] In the north ambulatory are the Islip Chapel, the Nurses' Memorial Chapel (sometimes called the Nightingale Chapel), the Chapel of Our Lady of the Pew,[109] the Chapel of St. John the Baptist, and St. Paul's Chapel.[110] The Islip Chapel is named after Abbot John Islip, who commissioned it in the 16th century. The screen inside is decorated with a visual pun on his name: an eye and a boy falling from a tree (eye-slip).[111] Additional chapels in the eastern aisle of the north transept are named after (from south to north) St. John the Evangelist, St. Michael, and St. Andrew.[112] The chapels of St. Nicholas, St. Edmund, and St. Benedict are in the south ambulatory.[113]

The footprint of the south transept is smaller than the northern one because the 13th-century builders butted against the pre-existing 11th-century cloisters. To make the transepts match, the south transept overhangs the western cloister; this permitted a room above the cloisters which was used to store the abbey muniments.[114] In the south transept is the chapel of St. Faith, built c. 1250 as the vestry for the abbey's monks. On the east wall is a c. 1290 – c. 1310 painting of St. Faith holding the grid-iron on which she was roasted to death.[115]

Chapter house and Pyx Chamber

The octagonal chapter house was used by the abbey monks for daily meetings, where they would hear a chapter of the Rule of St. Benedict and receive their instructions for the day from the abbot.[116] The chapter house was built between 1250 and 1259 and is one of the largest in Britain, measuring nearly 60 feet (18 m) across.[117] For 300 years after the English Reformation, it was used to store state records until they were moved to the Public Record Office in 1863.[118] It was restored by George Gilbert Scott in the 19th century.[119]

The entrance is approached from the east cloister via outer and inner vestibules, and the ceiling becomes higher as a visitor approaches the chapter house.[120] It is an octagonal room with a central pillar, built with a small crypt below.[119] Around the sides are benches for 80 monks, above which are large stained-glass windows depicting the coats of arms of several monarchs and the abbey's patrons and abbots.[119] The exterior includes flying buttresses (added in the 14th century) and a leaded roof designed by Scott.[121] The interior walls of the chapter house are decorated with 14th- and 15th-century paintings of the Apocalypse, the Last Judgement, and birds and animals.[121] The chapter house also has an original, mid-13th-century tiled floor. A wooden door in the vestibule, made with a tree felled between 1032 and 1064, is one of Britain's oldest.[121] It may have been the door to the 11th-century chapter house in Edward the Confessor's abbey, and was re-used as the door to the Pyx Chamber in the 13th century. It now leads to an office.[116]

The adjoining Pyx Chamber was the undercroft of the monks' dormitory. Dating to the late 11th century, it was used as a monastic and royal treasury. The outer walls and circular piers also date to the 11th century; several capitals were enriched in the 12th century, and the stone altar was added in the 13th century. The term pyx refers to the boxwood chest in which coins were held and presented to a jury during the Trial of the Pyx, when newly minted coins were presented to ensure they conformed to the required standards.[89] The chapter house and Pyx Chamber are in the guardianship of English Heritage, but under the care and management of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster.[122]

Henry VII Chapel

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

The Henry VII Lady Chapel, also known simply as the Henry VII Chapel, is a large lady chapel at the far eastern end of the abbey which was paid for by the will of King Henry VII.[124] The chapel, built in late Perpendicular Gothic style, inspired English poet John Leland to call it the orbis miraculum (the wonder of the world).[125] The tombs of several monarchs, including Edward V, Henry VII, Edward VI, Mary I, Elizabeth I, James I, Charles II, George II and Mary, Queen of Scots, are in the chapel.[126]

It is noted for its pendant- and fan vault-style ceiling, probably designed by William Vertue, which writer Washington Irving said was "achieved with the wonderful minuteness and airy security of a cobweb". The ceiling is not a true fan vault, but a groin vault disguised as a fan vault.[127] The interior walls are densely decorated with carvings, including 95 statues of saints. Many statues of saints in England were destroyed in the 17th century, so these are rare survivors.[70] Like much of the rest of the medieval building, they would originally have been painted and gilded.[128] From outside, The chapel walls are supported from outside by flying buttresses, each in the form of a polygonal tower topped with a cupola. At the centre of the chapel is the tomb of Henry VII and his wife, Elizabeth of York, which was sculpted by Pietro Torrigiano[125] (who fled to England from Italy after breaking Michaelangelo's nose in a fight).[70]

The chapel has sub-chapels radiating from the main structure. One, to the north, contains the tombs of Mary I and Elizabeth I; both coffins are in Elizabeth's monument. Another, to the south, contains the tomb of Mary, Queen of Scots. Both monuments were commissioned by James I, Elizabeth's successor to the English throne and Mary's son.[129] At the far eastern end is the RAF Chapel, with a stained-glass window dedicated to those who died in the 1940 Battle of Britain.[70] The RAF Chapel was the original burial site of Oliver Cromwell in 1658. Cromwell was disinterred in 1661, after the Stuart Restoration, when his body was ritually hanged on the gallows at Tyburn and then reburied.[130]

The chapel has been the mother church of the Order of the Bath since 1725, and the banners of its members hang above the stalls.[131] The stalls retain their medieval misericords: small ledges for monks to perch on during services, often decorated with varied and humorous carvings.[132]

Monastic buildings

Many rooms used by the monks have been repurposed. The dormitory became a library and a school room, and the monks' offices have been converted into houses for the clergy.[133] The abbot had his own lodgings, and ate separately from the rest of the monks. The lodgings, now used by the Dean of Westminster, are probably the oldest continuously occupied residence in London.[134] They include the Jericho Parlour (covered in wooden linenfold panelling), the Jerusalem Chamber (commissioned in 1369), and a grand dining hall with a minstrels' gallery which is now used by Westminster School.[134] The prior also had his own household, separate from the monks, on the site of present-day Ashburnham House in Little Dean's Yard (now also part of Westminster School).[135][136]

Artworks and treasures

The nave and transepts have sixteen crystal chandeliers made of hand-blown Waterford glass. Designed by A. B. Read and Stephen Dykes Bower, they were donated by the Guinness family in 1965 to commemorate the abbey's 900th anniversary.[137] The choir stalls were designed by Edward Blore in 1848.[100] Some stalls are assigned to high commissioners of countries in the Commonwealth of Nations.[138]

Beyond the crossing to the west is the sacrarium, which contains the high altar. The abbey has the 13th-century Westminster Retable, thought to be the altarpiece from Henry III's 13th-century church and the earliest surviving English panel painting altatrpiece, in its collections.[139][140] The present high altar and screen were designed by George Gilbert Scott between 1867 and 1873, with sculptures of Moses, St. Peter, St. Paul, and King David by H. H. Armistead, as well as a mosaic of the Last Supper by J. R. Clayton and Antonio Salviati.[141]

The south transept contains wall paintings made c. 1300, which Richard Jenkyns calls "the grandest of their time remaining in England".[142] Depicting Thomas the Apostle looking at Christ's wounds and St. Christopher carrying the Christ Child, the paintings were discovered in 1934 behind two monuments.[143] Fourteenth-century paintings are on the backs of the sedilia (seats used by priests on either side of the high altar). On the south side are three figures: Edward the Confessor, the angel Gabriel, and the Virgin Mary. On the north side are two kings (possibly Henry III and Edward I) surrounding a religious figure, possibly St. Peter.[144][145] They were walled off during the Commonwealth period by order of Parliament, and were later rediscovered.[145]

Over the Great West Door are ten statues of 20th-century Christian martyrs of various denominations; the statues were sculpted by the abbey's craftsmen in 1998.[146] Those commemorated are Maximilian Kolbe, Manche Masemola, Janani Luwum, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, Martin Luther King Jr., Óscar Romero, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Esther John, Lucian Tapiedi, and Wang Zhiming.[147][148]

From the chapter house is a doorway leading to the abbey's library, which was built as a dormitory for the monks and has been used as a library since the 16th century. The collection has about 16,000 volumes. Next to the library is the Muniment Room, where the abbey's historic archives are kept.[118]

Cosmati pavement

At the crossing in front of Edward the Confessor's shrine and the main altar is the Cosmati pavement, a 700-year-old tile floor made of almost 30,000 pieces of coloured glass and stone.[149] Measuring almost 25 feet square,[149] coronations take place here.[150]

The floor is named after the Cosmati family in Rome, who were known for such work.[29] It was commissioned by Richard Ware, who travelled to Rome in 1258, when he became abbot, and returned with stone and artists. The porphyry used was originally quarried as far away as Egypt, and was presumably brought to Italy during the Roman Empire. It was surrounded by a Latin inscription in brass letters (since lost) identifying the artist as Odericus,[151] probably referring to designer Pietro di Oderisio or his son.[152] The inscription also predicted the end of the world 19,863 years after its creation.[153] Unlike traditional mosaic work, the pieces were not cut to a uniform size but made using a technique known as opus sectile ("cut work").[149] It is unique among Cosmati floors in Europe for the use of dark Purbeck-marble trays, forming bold borders, instead of the more typical white marble.[149] The pavement influenced later floor treatments at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, and Canterbury Cathedral.[154]

Geometric designs, such as those in the pavement, were thought to help the abbey's monks with contemplation, and conveyed medieval Christian ideas on the nature of the universe that could not easily be put into words.[155] Much of the design relies on the geometric doubling of the square, considered a trade secret by stonemasons.[156] The four-sided squares, four-fold symmetry, and the four inner roundels of the design represent the four elements of classical philosophy, with the central roundel representing the unformed state of the universe at its creation.[157] Each inner roundel is touched by two bands, which represent the shared qualities of each element; water and air were both considered "moist" in classical philosophy, and air and fire were both considered "hot".[158]

Stained glass

The abbey's 13th-century windows would have been filled with stained glass, but much of this was destroyed in the English Civil War and the Blitz and was replaced with clear, plain glass. Since the 19th century, new stained glass, designed by artists such as Ninian Comper (on the north side of the nave) and Hugh Easton and Alan Younger (in the Henry VII Chapel), has replaced clear glass.[159]

The north rose window was designed by James Thornhill and made by Joshua Price in 1722; it shows Christ, the apostles (without Judas Iscariot), the Four Evangelists, and, in the centre, the Bible. The window was restored by J. L. Pearson in the 19th century, during which the feet of the figures were cut off.[160] Thornhill also designed the great west window, which shows the Biblical figures of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, as well as representatives of the Twelve Tribes of Israel underneath.[161]

In the Henry VII Chapel, the west window was designed by John Lawson and unveiled in 1995. It depicts coats of arms and cyphers of Westminster Abbey's benefactors, particularly John Templeton (whose coat of arms is prominent in the lower panel). In the centre are the arms of Elizabeth II. The central east window, designed by Alan Younger and dedicated to the Virgin Mary, was unveiled in 2000. It depicts Comet Hale–Bopp, which was passing over the artist's house at the time, as the star of Bethlehem. The donors of the window, Lord and Lady Harris of Peckham, are shown kneeling at the bottom.[162]

In 2018, artist David Hockney unveiled a new stained-glass window for the north transept to celebrate the reign of Elizabeth II. It shows a country scene inspired by his native Yorkshire, with hawthorn blossoms and blue skies. Hockney used an iPad to design the window, replicating the backlight that comes through stained glass.[163]

Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries

The Westminster Abbey Museum was located in the 11th-century vaulted undercroft beneath the former monks' dormitory. This is one of the oldest areas of the abbey, dating almost to the foundation of the church by Edward the Confessor in 1065. This space had been used as a museum since 1908,[164] but was closed to the public when it was replaced as a museum in June 2018 by the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries (high in the abbey's triforium and accessed through the Weston Tower, which encloses a lift and stairs).[82]

The exhibits include a set of life-size effigies of English and British monarchs and their consorts, originally made to lie on the coffin in the funeral procession or to be displayed over the tomb. The effigies date from the 14th to the 18th centuries, and some include original clothes.[165]

On display in the galleries is The Coronation Theatre, Westminster Abbey: A Portrait of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, a portrait by Ralph Heimans of the queen standing on the Cosmati pavement where she was crowned in 1953.[166] Other exhibits include a model of an unbuilt tower designed by Christopher Wren; a paper model of the abbey as it was for Queen Victoria's 1837 coronation; and the wedding licence of Prince William and Catherine Middleton, who were married in the abbey in 2011.[83]

Burials and memorials

Over 3,300 people are buried or commemorated in the abbey.[167] For much of its history, most of the people buried there (other than monarchs) were people with a connection to the church – either ordinary locals or the monks of the abbey, who were generally buried without surviving markers.[168] Since the 18th century, it has been an honour for any British person to be buried or commemorated in the abbey – a practice boosted by the lavish funeral and monument of Isaac Newton, who died in 1727.[169] By 1900, so many prominent figures were buried in the abbey that the writer William Morris called it a "National Valhalla".[170]

Politicians buried in the abbey include Pitt the Elder, Charles James Fox, Pitt the Younger, William Gladstone, and Clement Attlee. A cluster of scientists surrounds the tomb of Isaac Newton, including Charles Darwin and Stephen Hawking. Actors include David Garrick, Henry Irving, and Laurence Olivier. Musicians tend to be buried in the north aisle of the nave, and include Henry Purcell and Ralph Vaughan Williams. George Frideric Handel is buried in Poets' Corner.[171]

An estimated 18 English, Scottish and British monarchs are buried in the abbey, including Edward the Confessor, Henry III, Edward I, Edward III, Richard II, Henry V, Edward V, Henry VII, Edward VI, Mary I, Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, James I, Charles II, Mary II, William III, Queen Anne, and George II.[172][165] Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots were the last monarchs to be buried with full tomb effigies; monarchs buried after them are commemorated in the abbey with simple inscriptions.[173] George II was the last monarch to be buried in the abbey, in 1760, and George III's brother, Henry Frederick, was the last member of the royal family to be buried in the abbey, in 1790. Most monarchs after George II have been buried in St. George's Chapel, Windsor, or at the Frogmore Royal Burial Ground, east of Windsor Castle.[60]

Poets' Corner

The south transept of the church is known as Poets' Corner because of its high number of burials of, and memorials to, poets and writers. The first was Geoffrey Chaucer (buried around 1400), who was employed as Clerk of the King's Works and had apartments in the abbey. A second poet, Edmund Spenser (who was local to the abbey), was buried nearby in 1599. The idea of a Poets' Corner did not crystallise until the 18th century, when memorials were established to writers buried elsewhere, such as William Shakespeare and John Milton. Since then, writers buried in Poets' Corner have included John Dryden, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens, and Rudyard Kipling. Not all writers buried in the abbey are in the south transept; Ben Jonson is buried standing upright in the north aisle of the nave, and Aphra Behn in the cloisters.[174]

The Unknown Warrior

On the floor, just inside the Great West Door in the centre of the nave, is the grave of the Unknown Warrior: an unidentified soldier killed on a European battlefield during the First World War. Although many countries have a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (or Warrior), the one in Westminster Abbey was the first; it came about as a response to the unprecedented death toll of the war.[175] The idea came from army chaplain David Railton, who suggested it in 1920.[176] The funeral was held on 11 November 1920, the second anniversary of the end of the war.[175] The Unknown Warrior lay in state for a week afterwards, and an estimated 1.25 million people viewed his gravesite in that time. This grave is the only floor stone in the abbey on which it is forbidden to walk,[177] and every visit by a foreign head of state begins with a visit to it.[176]

Royal occasions

The abbey has strong connections with the royal family. It has been patronised by monarchs, been the location for coronations, royal weddings and funerals, and several monarchs have attended services there. One monarch was born and one died at Westminster Abbey. In 1413, Henry IV collapsed while praying at the shrine of Edward the Confessor. He was moved into the Jerusalem Chamber, and died shortly afterwards.[178] Edward V was born in the abbot's house in 1470.[38]

The first jubilee celebration held at the abbey was for Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887. Rather than wearing the full regalia that she had worn at her coronation, she wore her black mourning clothes topped with the insignia of the Order of the Garter and a miniature crown. She sat in the Coronation Chair—which received a coat of dark varnish for the occasion, which was painstakingly removed afterwards[179]—making her the only monarch to sit in the chair twice.[180] Queen Elizabeth II and her husband, Prince Philip, marked their silver, gold, and diamond wedding anniversaries with services at the abbey and regularly attended annual observances there for Commonwealth Day.[175]

The monarch participates in the Office of the Royal Maundy on Maundy Thursday each year, during which selected elderly people (as many people of each sex as the monarch has years of their life) receive alms of coins. The service has been held at churches around the country since 1952, returning to the abbey every 10 years.[181]

Coronations

Since the coronation of William the Conqueror in 1066, 40 English and British monarchs have been crowned in Westminster Abbey (not counting Edward V, Lady Jane Grey, and Edward VIII, who were never crowned).[182][183] In 1216, Henry III could not be crowned in the abbey because London was occupied by hostile forces at the time. Henry was crowned in Gloucester Cathedral, and had a second coronation at Westminster Abbey in 1220.[139] When he had the abbey rebuilt, it was designed with long transepts to accommodate many guests at future coronations.[95] Much of the order of service derives from the Liber Regalis, an illuminated manuscript made in 1377 for the coronation of Richard II and held in the abbey's collections.[184] On 6 May 2023, the coronation of Charles III took place at the abbey.[183] The area used in the church is the crossing, known in the abbey as "the theatre" because of its suitability for grand events. The space in the crossing is clear rather than filled with immovable pews (like many similar churches), allowing for temporary seating in the transepts.[182]

The Coronation Chair (the throne on which English and British sovereigns are seated when they are crowned) is in the abbey's St. George's Chapel near the west door, and has been used at coronations since the 14th century.[185] From 1301 to 1996 (except for a short time in 1950, when the stone was stolen by Scottish nationalists), the chair housed the Stone of Scone upon which the kings of Scots were crowned. Although it has been kept in Scotland at Edinburgh Castle since 1996, the stone is returned to the Coronation Chair in the abbey as needed for coronations.[186] The chair was accessible to the public during the 18th and 19th centuries; people could sit in it, and some carved initials into the woodwork.[187]

Before the 17th century, a king would hold a separate coronation for his new queen if he married after his coronation. The last of these to take place in the abbey was the coronation of Anne Boleyn in 1533, after her marriage to Henry VIII.[45] Fifteen coronations of queens consort have been held in the abbey. A coronation for Jane Seymour, Henry VIII's third wife, was planned but she died before it took place; no coronations were planned for Henry's subsequent wives. Mary I's husband, Philip of Spain, was not given a separate coronation due to concerns that he would attempt to rule alone after Mary's death. Since then, there have been few opportunities for a second coronation; monarchs have generally come to the throne already married.[182]

Henry II held a coronation ceremony at Westminster Abbey in 1170 for his son, known as Henry the Young King, while Henry II was still alive in an attempt to secure the succession. However, the Young King died before his father and never took the throne.[182]

Weddings

At least 16 royal weddings have taken place at the abbey.[188] Royal weddings at the abbey were relatively rare before the 20th century, with royals often married in a Chapel Royal or at Windsor Castle; this changed with the 1922 wedding of Princess Mary at the abbey. In 1923, Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon became the first royal bride to leave her bouquet on the grave of the Unknown Warrior, a practice continued by many royal brides since.[189]

Royal weddings have included:

Funerals

Many royal funerals took place at the abbey between that of Edward the Confessor in 1066[31] and that of Prince Henry, the last royal buried in the church, in 1790. There were no royal funerals at the abbey from then until that of Queen Alexandra in 1925; the queen was buried in Windsor Castle.[193] Other queen consorts, such as Mary of Teck in 1953 and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in 2002, have also had funerals at the abbey before being buried elsewhere.[193]

On 6 September 1997, the ceremonial funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales was held at the abbey. Before the funeral, the railings of the abbey were swamped with flowers and tributes. The event was more widely seen than any previous occasion in the abbey's history, with 2 billion television viewers worldwide.[194] Diana was buried privately on a private island at Althorp, her family estate.[195]

On 19 September 2022, the state funeral of Elizabeth II took place at the abbey before her burial at St George's Chapel, Windsor.[196] It was the first funeral of a monarch at Westminster Abbey for more than 260 years.[197]

People

Dean and Chapter

Westminster Abbey is a collegiate church governed by the Dean and Chapter of Westminster as established by a royal charter from Elizabeth I dated 21 May 1560, which created it as the Collegiate Church of St. Peter Westminster (a royal peculiar).[198] In 2019, David Hoyle was appointed Dean of Westminster.[199] The chapter consists of four canons and a senior administrative officer, known as the Receiver General.[198] One of the canons is also rector of the adjoining St Margaret's Church, Westminster, and is often the chaplain of the Speaker of the House of Commons.[200] In addition to the dean and canons, there are minor canons.[201]

King's almsmen

Six King's (or Queen's) almsmen and women are supported by the abbey. They are appointed by royal warrant on the recommendation of the dean and the Home Secretary, attend Matins and Evensong on Sundays, and perform requested duties for a small stipend. On duty, they wear a distinctive red gown with a crowned rose badge on the left shoulder.[202]

The almshouse was founded near the abbey by Henry VII in 1502, and the twelve almsmen and three almswomen were originally minor court officials who were retired due to age or disability.[203] They were required to be over the age of 50, single, with a good reputation, literate, able to look after themselves, and with an income of under £4 per year.[203] The building survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but was demolished for road-widening in 1779.[202] From the late 18th to the late 20th century, almsmen were usually old soldiers and sailors; today, they are primarily retired abbey employees.[202]

Schools

Westminster School is in the abbey. Instruction has taken place since the fourteenth century with the monks of the abbey; the school regards its founder as Elizabeth I, who dissolved the monastery for the last time and provided for the establishment of the school,[204] the dean, canons, assistant clergy, and lay officers.[205] The schoolboys were rambunctious; Westminster boys have defaced the Coronation Chair, disrupted services, and once interrupted the consecration of four bishops with a bare-knuckle fight in the cloisters.[204] One schoolboy carved on the Coronation Chair that he had slept in it overnight, making him probably its longest inhabitant.[206] Westminster School became independent of the abbey Dean and Chapter in 1868, although the institutions remain closely connected.[205] Westminster Abbey Choir School, also on the abbey grounds, educates the choirboys who sing for abbey services.[207]

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry whose spiritual home is the abbey's Henry VII Chapel.[60] The order was founded by George I in 1725,[208] fell out of fashion after 1812, and was revived by George V in 1913.[209] The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which included bathing as a symbol of purification.[60] Members are given stalls with their banner, crest, and a stall plate at installation ceremonies in the abbey every four years.[210] Since there are more members than stalls, some members wait many years for their installation.[211] The Order of the Bath is the fourth-oldest British orders of chivalry, after the Orders of the Garter, the Thistle, and St. Patrick (the latter is presently dormant).[212]

Music

Andrew Nethsingha has been the abbey's organist and master of the choristers since 2023.[213] Peter Holder is the sub-organist,[214] Matthew Jorysz the assistant organist,[215] and Dewi Rees is the organ scholar.[216]

Choir

Since its foundation in the fourteenth century, the primary role of the Westminster Abbey choir has been to sing for daily services; the choir also plays a central role in many state occasions, including royal weddings and funerals, coronations, and memorial services.[217] In 2012, the choir accepted an invitation from Pope Benedict XVI to sing with the Sistine Chapel Choir at a Papal Mass in St. Peter's Basilica.[218] The all-male choir consists of twelve professional adult singers and thirty boy choristers from eight to 13 years old who attend the Westminster Abbey Choir School.[219]

Organ

The first record of an organ at Westminster Abbey was the mention of a gift of three marks from Henry III in 1240 for the repair of one (or more) organs.[220] Unum parem organorum ("a pair of organs") was recorded in the Lady Chapel in 1304.[220] An inventory compiled for the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1540 lists a pair of organs in the choir and one in the Islip Chapel.[220] During the Commonwealth, a Royalist source said that soldiers who were billeted in the abbey "brake downe the Organ, and pawned the pipes at severall Ale-houses for pots of Ale"; an organ was played at the Restoration in 1660, however, suggesting that it had not been completely destroyed.[220] In 1720, an organ gifted by George II and built by Christopher Shrider was installed over the choir screen; organs had previously been hidden on the north side of the choir. The organ was rebuilt by William Hill & Son in 1848.[220]

A new organ was built by Harrison & Harrison in 1937, with four manuals and 84 speaking stops, and was played publicly for the first time at the coronation of George VI and Elizabeth that year.[221] Some pipework from the previous Hill organ of 1848 was re-voiced and incorporated into the new instrument. The two organ cases, designed and built in the late 19th century by J. L. Pearson, were reinstated and coloured in 1959.[222]

In 1982 and 1987, Harrison & Harrison enlarged the organ at the direction of Simon Preston to include an additional lower choir organ and a bombarde organ.[221] The full instrument has five manuals and 109 speaking stops. Its console was refurbished by Harrison & Harrison in 2006, and space was prepared for two additional 16-foot stops on the lower choir organ and the bombarde organ.[222] The abbey has three other organs: the two-manual Queen's Organ in the Lady Chapel, a smaller continuo organ, and a practice organ.[219]

Bells

There have been bells at the abbey since at least the time of Henry III, and the current bells were installed in the north-west tower in 1971.[223] The ring is made up of ten bells, hung for change ringing, which were cast in 1971 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and tuned to the musical notes F#, E, D, C#, B, A, G, F#, E and D. The tenor bell in D (588.5 Hz) has a weight of 30 cwt, 1 qtr, 15 lb (3,403 lb, or 1,544 kg).[224] Two additional service bells were cast by Robert Mot in 1585 and 1598, and a sanctus bell was cast in 1738 by Richard Phelps and Thomas Lester. Two bells are unused; one was cast c. 1320, and the second was cast in 1742 by Thomas Lester.[224] The Westminster Abbey Company of Ringers ring peals on special occasions, such as the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton.[225]

In popular culture

Westminster Abbey is mentioned in the play Henry VIII by William Shakespeare and John Fletcher, when a gentleman describes Anne Boleyn's coronation.[226] The abbey was mentioned in a 1598 sonnet by Thomas Bastard which begins, "When I behold, with deep astonishment / To famous Westminster how there restort / Living in brass or stony monument / The princes and the worthies of all sort".[227] Poetry about the abbey has also been written by Francis Beaumont[227] and John Betjeman.[228] The building has appeared in paintings by artists such as Canaletto,[60] Wenceslaus Hollar,[229] William Bruce Ellis Ranken,[230] and J. M. W. Turner.[231]

Playwright Alan Bennett produced The Abbey, a 1995 documentary recounting his experiences of the building.[232] Key scenes in the book and film The Da Vinci Code take place in Westminster Abbey.[233] The abbey refused to allow filming in 2005 (calling the book "theologically unsound"), and the film uses Lincoln Cathedral as a stand-in.[234] The abbey issued a fact sheet to their staff which answered questions and debunked several claims made in the book.[235] In 2022, it was announced that the abbey had given rare permission to film inside the church for the untitled eighth Mission: Impossible film.[236]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ a b c d "Dimensions of Westminster Abbey" (PDF). Westminster Abbey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Westminster Abbey (The Collegiate Church of St Peter)". Historic England. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Cavendish, Richard (12 December 2015). "The consecration of Westminster Abbey". History Today. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Summerson 2019, p. 17.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Summerson 2019, p. 27.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2013, p. 6.

- ^ a b Corrigan 2018, p. 148.

- ^ Corrigan 2018, p. 159.

- ^ Harvey 1993, p. 2.

- ^ Fernie 2009, pp. 139–143.

- ^ Stafford 2009, p. 137.

- ^ Carr 1999, p. 2.

- ^ Trowles 2008, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Harvey 1993, p. 6.

- ^ Binski & Clark 2019, p. 51.

- ^ Clark & Binski 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Harvey 1993, p. 5.

- ^ Harvey 1993, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Colvin, H.M (1963). The History of the King's Works (2nd ed.). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 149. ISBN 0116704497.

- ^ Bartlett, Suzanne (2009). Licoricia of Winchester: Marriage, motherhood and murder (1st ed.). London, Portland (Oregon): Valentine Mitchell. p. 59. ISBN 9780853038221.

- ^ a b Jenkyns 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Corrigan 2018, p. 56.

- ^ a b Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Corrigan 2018, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 405.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, pp. 30–33.

- ^ a b Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 35.

- ^ a b Trowles 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Rodwell 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Rodwell 2010, pp. 23–28.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Jenkyns 2004, p. 13.

- ^ a b Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Harvey 2007.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 44.

- ^ a b Jenkyns 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Horn 1992, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Brewer 2001, p. 923.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, pp. 49.

- ^ Merritt 2019, p. 187.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 53.

- ^ a b Jenkyns 2004, p. 64.

- ^ Ashley, Maurice; Morrill, John S. "Oliver Cromwell: Administration As Lord Protector". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Black 2007, p. 253.

- ^ a b c d e Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 113.

- ^ Crook 2019, pp. 286–293.

- ^ a b c Webb 2014, p. 148.

- ^ Jones 2016, p. 65.

- ^ a b Cannadine 2019, pp. 336–338.

- ^ "General Structure of the Abbey Intact". The Scotsman. 13 May 1941. p. 5. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Famous London buildings severely damaged". Irish Independent. 12 May 1941. p. 5. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Westminster Abbey: £135,000 Damage in Raids". Belfast News-Letter. 17 May 1941. p. 6. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Cannadine 2019, p. 341.

- ^ Lutyens, Edwin Landseer (1943). "Preliminary designs for a proposed narthex for Westminster Abbey". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret's Church". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ "Westminster Abbey now example of how to handle tourists". Episcopal News Service. 6 March 2002. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 112.

- ^ a b "Building work announced for Abbey". BBC News. 28 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (29 June 2009). "Dean lines up new crown shaped roof for Westminster Abbey". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "Abbey Development Plan Update". Westminster Abbey (Press release). 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (5 May 2008). "Carpet of stone: medieval mosaic pavement revealed". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 17 May 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Schjonberg, Mary Frances (17 September 2010). "Benedict becomes first pope to visit Lambeth, Westminster Abbey". Episcopal News Service. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Royal wedding: Prince William and Kate Middleton marry". BBC News. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ a b "The Queen opens The Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries with the Prince of Wales". The Royal Household. 8 June 2018. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ a b c Wainwright, Oliver (29 May 2018). "'A gothic space rocket to a secret realm' – Westminster Abbey's new £23m tower". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Brown, Mark (23 August 2020). "Lost medieval sacristy uncovered at Westminster Abbey". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Vanderhoof, Erin (23 March 2021). "Kate and William Visit One of the U.K.'s Most Surprising Vaccination Clinics". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 404.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 45.

- ^ a b Carr 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, pp. 462–463.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 160.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 161.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (14 December 2016). "New tower will reveal hidden world of Westminster Abbey". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 407.

- ^ a b Trowles 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, pp. 415–416.

- ^ a b Trowles 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Trowles 2008, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 15.

- ^ a b Jenkyns 2004, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 71.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 57.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Trowles 2008, pp. 60–66.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 61.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 53.

- ^ Trowles 2008, pp. 75–79.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 80.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 97.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Trowles 2008, pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Trowles 2008, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Trowles 2008, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 467.

- ^ a b c "The Chapter House and Pyx Chamber in the abbey cloisters, Westminster Abbey". Historic England. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Chapter House and Pyx Chamber". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "Henry VII Chapel". Smarthistory. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 126.

- ^ a b Jenkyns 2004, pp. 48–53.

- ^ Lindley 2003, p. 208.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 418.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 417.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, pp. 60–61.

- ^ "Westminster Abbey Burials – Famous People Buried Among Kings At Westminster Abbey". 10 August 2021.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 127.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 25.

- ^ Carr 1999, p. 4.

- ^ a b Trowles 2008, p. 159.

- ^ MacCulloch 2019, p. 147.

- ^ Crook 2019, p. 311.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 120.

- ^ Carr 1999, p. 21.

- ^ a b Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 15.

- ^ Binski & Clark 2019, p. 81.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 96.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 29.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 149.

- ^ Heller, Jenny E. (22 September 1998). "Westminster Abbey Elevates 10 Foreigners". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Streeter, Michael (17 October 1997). "Heritage: Westminster Abbey prepares modern martyrs' corner". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d Trowles 2008, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Grierson, Jamie (24 March 2023). "Public invited to walk on Westminster Abbey's Cosmati pavement – in socks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Fawcett 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Foster 1991, p. 4.

- ^ Foster 1991, pp. 116–118.

- ^ Foster 1991, pp. 152–154.

- ^ Foster 1991, p. 155.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 148.

- ^ Reynolds 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Reynolds 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Reynolds 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Brown, Mark (26 September 2018). "David Hockney unveils iPad-designed window at Westminster Abbey". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 156.

- ^ a b Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, pp. 51–52.

- ^ "Queen portrait unveiled in Australia". BBC News. 29 September 2012. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Castle, Stephen (15 June 2018). "Stephen Hawking Enters 'Britain's Valhalla,' Where Space Is Tight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 63.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Morris 1900, p. 37.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, pp. 75–78.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, pp. 78–81.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 79.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2013, p. 37.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 167.

- ^ Robinson 1992, p. ix.

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 61.

- ^ a b FitzGerald, James; Owen, Emma; Moloney, Marita; Therrien, Alex (6 May 2023). "Coronation live: Charles and Camilla crowned King and Queen at Westminster Abbey". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 62.

- ^ Wilkinson 2013, p. 11.

- ^ "Stone of Destiny heads south for coronation". BBC News. 28 April 2023. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 68.

- ^ Hassan, Jennifer (8 January 2023). "Royal Treatment". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 174.

- ^ a b c Weir 2011, pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 77.

- ^ Barford, Vanessa; Pankhurst, Nigel (18 November 2010). "Is Westminster Abbey the ultimate royal wedding venue?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ a b Stubbings, David (19 September 2022). "The Kings and Queens buried at Westminster Abbey across 700 years". Shropshire Star. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 80.

- ^ "Diana Returns Home". BBC News. 1997. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Foster, Max; McGee, Luke; Owoseje, Toyin (19 September 2022). "Who's on the guest list for Queen Elizabeth II's state funeral?". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Hirwani, Peoni (19 September 2022). "The significance of Westminster Abbey, where the Queen's funeral service is taking place". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Westminster Abbey 2022 Annual Report to the Visitor, His Majesty the King" (PDF). Westminster Abbey. pp. 38–42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Beaney, Abigail (19 September 2022). "Waterfoot born Dean led funeral of Queen Elizabeth II". Lancashire Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Interview: Robert Wright, Sub-dean of Westminster Abbey, Rector of St Margaret's". Church Times. 26 May 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "Royal Appointments". Crockford's Clerical Directory. Archived from the original on 28 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Fox, Christine Merie (2012). The Royal Almshouse at Westminster c. 1500 – c. 1600 (PDF). pp. 248–250. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- ^ a b Fox, Christine Merie (2015). "The Tudor Royal Almsmen 1500-1600". Medieval Prosopography. 30: 139–176. ISSN 0198-9405. JSTOR 44946928.

- ^ a b Jenkyns 2004, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Trowles 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Jenkyns 2004, p. 65.

- ^ "Making all the right noises: An Interview with Jonathan Milton, headmaster of the Westminster Abbey Choir School". KCW Today. 15 September 2017. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ Duckers 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Cannadine 2019, p. 326.

- ^ Duckers 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Wilkinson & Knighton 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Duckers 2004, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Savage, Mark (26 April 2023). "King's Coronation: Conducting the Westminster Abbey service is a 'daunting job'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 July 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Wright, Steve (4 June 2023). "All about Peter Holder, Westminster Abbey sub-organist". Classical Music. BBC Music Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Coronation Music at Westminster Abbey". The Royal Household. 23 February 2023. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Westminster Abbey Organist Appointed at Bath Abbey". Bath Abbey. 9 March 2023. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Nepilova, Hannah (14 August 2022). "Westminster Abbey Choir: our guide to the world-famous Abbey choir". Classical Music. BBC Music Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 September 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Choir of Westminster Abbey invited to sing at Vatican". The Times. 8 October 2023. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ a b Shaw Roberts, Maddy (5 May 2023). "Music at Westminster Abbey – who are the choristers and organists, and what services are there?". Classic FM. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Knight, David Stanley (2001). The Organs of Westminster Abbey and their Music, 1240–1908 (Doctoral thesis). King's College London.

- ^ a b "Westminster Abbey" (PDF). Harrison & Harrison. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Westminster Abbey (St. Peter), Broad Sanctuary, Westminster, Middlesex [N00646]". The National Pipe Organ Register. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Trowles 2008, p. 123.