First Philippine Republic: Difference between revisions

Sanglahi86 (talk | contribs) →Seats of government: Refined pushpin map. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Use Philippine English|date=December 2022}} |

{{Use Philippine English|date=December 2022}} |

||

{{Infobox former country |

{{Infobox former country |

||

| native_name = {{native name|es|República Filipina}}<br />{{native name|tl| |

| native_name = {{native name|es|República Filipina}}<br />{{native name|tl|Republica ng Pilipinas}} |

||

| conventional_long_name = Philippine Republic |

| conventional_long_name = Philippine Republic |

||

| common_name = Philippines, Republic First |

| common_name = Philippines, Republic First |

||

Revision as of 08:09, 29 August 2024

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Philippine Republic (Template:Lang-es), now officially remembered as the First Philippine Republic and also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was established in Malolos, Bulacan during the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire (1896–1898) and the Spanish–American War between Spain and the United States (1898) through the promulgation of the Malolos Constitution on January 23, 1899, succeeding the Revolutionary Government of the Philippines. It was formally established with Emilio Aguinaldo as president.[11] It was unrecognized outside of the Philippines but remained active until April 19, 1901.[b] Following the American victory at the Battle of Manila Bay, Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines, issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence on June 12, 1898, and proclaimed successive revolutionary Philippine governments on June 18 and 23 of that year.

In December 1898, Spain and the United States signed the 1898 Treaty of Paris, ending the Spanish–American war. As part of the treaty, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States. The treaty was not formally proclaimed until April 11, 1899, when mutual ratifications were exchanged. In the meantime, on January 23, 1899, the Malolos Constitution establishing the First Philippine Republic had been proclaimed and, on February 4, 1899, fighting had erupted in Manila between American and Filipino forces in what developed into the Philippine–American War.[e] Aguinaldo was captured by the American forces on March 23, 1901, in Palanan, Isabela, he declared allegiance to the U.S. on April 19, 1901, effectively ending the Philippine Republic.[14][15]

The First Philippine Republic is sometimes characterized as the first proper constitutional republic in Asia,[16][17][18] although there were several Asian republics predating it – for example, the Mahajanapadas of ancient India, the Lanfang Republic, the Republic of Formosa, or the Republic of Ezo. Aguinaldo himself had led a number of governments prior to Malolos, like those established at Tejeros and Biak-na-Bato which both styled themselves República de Filipinas ("Republic of the Philippines"). Unlike the founding documents of those governments, however, the Malolos Constitution was duly approved by a partially elected congress and called for a true representative democracy.[11][19]

History

In 1896, the Philippine Revolution began against Spanish colonial rule. In 1897, Philippine forces led by Aguinaldo signed a ceasefire with the Spanish authorities and Aguinaldo and other leaders went into exile in Hong Kong. In April 1898, the Spanish–American War broke out. The U.S. Navy's Asiatic Squadron, then in Hong Kong, sailed to the Philippines to engage the Spanish naval forces. On May 1, 1898, the U.S. Navy decisively defeated the Spanish Naval force and blockaded Manila Bay.[20] The American naval commander, lacking forces to conduct land operations following his unexpectedly complete victory, returned Aguinaldo and a number of other revolutionary exiles to the Philippines from Hong Kong.[21]

Aguinaldo arrived in the Philippines on May 24 and on that date, proclaimed a dictatorial government, rekindling the Philippine Revolution[22][23] (formally established by decree on June 18[24]). On June 12, he issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence from Spain at his ancestral home in Cavite. He established a revolutionary government on June 23, under which the partly-elected and partly-appointed Malolos Congress convened on September 15 to write a constitution.[25]

On December 10, 1898, the 1898 Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the Spanish–American War and transferring the Philippines from Spain to the United States.[26]

The constitution written by the Malolos Congress was proclaimed on January 22, 1899, creating what is known today as the First Philippine Republic, with Aguinaldo as its president.[27][22] The constitution was approved by delegates to the Malolos Congress on January 20, 1899, and sanctioned by Aguinaldo the next day.[27] The convention had earlier elected Aguinaldo president on January 1, 1899, leading to his inauguration on January 23. Parts of the constitution gave Aguinaldo the power to rule by decree.[f] The constitution was titled "Constitución política", and was written in Spanish.[29][27][30]

Philippine–American War

When the First Philippine Republic was constituted on January 22, 1899, in Malolos, that municipality became the seat of government of the Philippine Republic, and was serving as such when hostilities erupted between U.S. and Filipino forces in the Second Battle of Manila on February 4.[31] On February 4, 1899, armed conflict erupted in Manila between Philippine Republic forces and American forces occupying the city subsequent to the conclusion of the Spanish–American War.[32] That day President Aguinaldo issued a proclamation ordering and commanding that "peace and friendly relations with the Americans be broken and that the latter be treated as enemies, within the limits prescribed by the laws of war".[33] The fighting quickly escalated into the Second Battle of Manila, with Philippine Republic forces being driven out of the city.[34]

American forces pushing north from Manila after the outbreak of fighting captured Caloocan on February 10.[35] On March 29, as American forces threatened Malolos, the seat of government moved to San Isidro, Nueva Ecija.[36] On March 31, American forces captured Malolos, the initial seat of the Philippine Republic government, which had been gutted by fires set by withdrawing Philippine Republic forces.[37] Emilio Aguinaldo and the core of the revolutionary government had by then moved to San Isidro, Nueva Ecija.[38] Peace negotiations with the American Schurman Commission during a brief ceasefire in April–May 1899 failed,[38] and San Isidro fell to American forces on May 16.[39] The Philippine Republic core government had moved by then to Bamban, Tarlac, and subsequently moved to Tarlac town.[40] Aguinaldo's party had already left Tarlac, the last capital of the Philippine Republic, by the time American troops occupied it on November 13.[41]

American forces captured Calumpit, Bulacan on April 27 and, moving north, captured Apalit, Pampanga with little opposition on May 4 and San Fernando, Pampanga on May 5. This forced the seat of government to be shifted according to the demands of the military situation.[42]

In October 1899, American forces were in San Fernando, Pampanga and the Philippine Republic was headquartered not far north of there, in Angeles City. On October 12, an American offensive to the north forced the Philippine Republic to relocate its headquarters in November to Tarlac, and then to Bayambang, Pangasinan.[43] On November 13, under pressure by American forces, Aguinaldo and a party departed Bayambang by rail for Calasiao, from where they immediately proceeded eastwards to Santa Barbaraa in order to evade pursuing American forces. There, they joined a force of some 1200 armed men led by General Gregorio del Pilar.[44]

Aguinaldo had decided in aa November 13 conference in Bayambang to disperse his army and begin guerrilla war. From that point on, distance and the localistic nature of the fighting prevented him from exercising a strong influence on revolutionary or military operations.[41] Recognizing that American troops blocked his escape east, he turned north and west on November 15, crossing the mountains into La Union province.[45] Aguinaldo's party eluded pursuing American forces, passing through Tirad Pass near Sagada, Mountain Province where the Battle of Tirad Pass was fought on December 2 as a rear guard action to delay the American advance and ensure his escape. At the time of the battle, Aguinaldo and his party were encamped in Cervantes, about 10 km south of the pass. After being notified by a rider of the outcome of the battle and the death of del Pilar, Aguinaldo ordered that camp be broken, and departed with his party for Cayan settlement.[46]

Aguinaldo's party, traveling with del Pilar's force, reached Manaoag, Pangasinan on November 15. There, the force was split into vanguard and rear guard elements, with Aguinaldo and del Pilar in the vanguard.[47] The vanguard force overnighted in Tubao, La Union, departed there on November 16, and was in Naguilian, La Union by November 19, where word was received that American forces had taken Santo Tomas and had proceeded to Aringay. Aguinaldo's force arrived in Balaoan, La Union on November 19, pushed on the next day, and arrived at the Tirad Pass, a natural choke point, on November 23. General del Pilar decided to place a blocking force in Tirad Pass to delay pursuing American forces while Aguinaldo's party moved on.[48]

The Battle of Tirad Pass took place on December 2, 1899. 52 men of del Pilar's 60-man force were killed, including del Pilar himself. However, the Filipinos under del Pilar held off the Americans long enough for Aguinaldo's party to escape. Aguinaldo, encamped with his party about 10 km south of the pass in Cervantes, Ilocos Sur, was apprised of the result of the battle by a rider, and moved on. The party reached Banane settlement on December 7, where Aguinaldo paused to consider plans for the future. On December 16, the party departed for Abra to join forces with General Manuel Tinio.[49] The party traveled on foot through a pass at the summit of Mount Polis, and arrived at Ambayuan the next morning. The party pushed on to Banane, pursued closely by American forces. At this point, Aguinaldo's party consisted of one field officer, 11 line officers, and 107 men. The remainder of December 1899 was spent in continuous trek.[50]

The party was at the border of Abra and Cagayan provinces on Aguinaldo's 31st birthday on March 23, 1900. The trek from place to place continued until about May 22, 1900, when Aguinaldo established a new headquarters in Tierra Virgen.[51] On August 27, 1900, after American forces landed at Aparri, Cagayan, Aguinaldo concluded that Tierra Virgan had become untenable as a headquarters and decided to march to Palanan, Isabela.[51] On December 6, 1900, the party reached Dumasari, and arrived in Palanan the following morning.[52]

Aguinaldo remained in Palanan until his capture there by American forces with the aid of the native scouts on March 23, 1901.[52] Following his capture, Aguinaldo announced allegiance to the United States on April 19, 1901 and manifesting to the Philippine people to lay down their weapons, formally ending the First Republic and recognizing the sovereignty of the United States over the Philippines.[b]

Fighting between the Americans and the remnants of the Philippine Republican Army continued until the surrender of General Miguel Malvar on April 16, 1902.[53]

Organization

Presidency

Executive power was exercised by the President, through his cabinet secretaries. The incumbent president of the Revolutionary Republic initially assumed the presidency. Presidents were to be elected by the legislature to terms of four years and to be eligible for reelection.

In addition to his basic powers, the 1899 Constitution assigned the following duties to the presidency:[9]

- Confer civil and military employment in accordance to the law

- Appoint Secretaries of Government

- Direct diplomatic and commercial relations with other countries

- Ensure the swift and complete administration of justice in the entire national territory

- Pardon criminal offenders in accordance with the law, subject to the provisions relating to the Secretaries of Government

- Preside over national solemnities, and welcome accredited envoys and representatives of foreign countries with relations to the Republic

National cabinet

The constitution established a Council of Government (Cabinet), composed of a President and seven Secretaries. The following individuals were appointed to Cabinet positions:[55]

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| President | Emilio Aguinaldo | January 23, 1899 – April 19, 1901 |

| President of the Cabinet[56][57][58] | Apolinario Mabini | January 2 – May 7, 1899[58] |

| Pedro Paterno | May 7 – November 13, 1899[58][g] | |

| Secretary of Foreign Affairs[56][57] | Apolinario Mabini | October 1, 1898 – May 7, 1899[58] |

| Secretary of the Interior[56][57] | Teodoro Sandico | January 2 – May 7, 1899[58] |

| Secretary of Finance[56][57] | Mariano Trías | January 2 – May 7, 1899[58] |

| Hugo Ilagan | May 7 – November 13, 1899[58][g] | |

| Severino de las Alas | May 7 – November 13, 1899[58][g] | |

| Secretary of War and Marine[56][57] | Baldomero Aguinaldo | July 15, 1898 – May 7, 1899[58] |

| Mariano Trías | May 7 – November 13, 1899[58][g] | |

| Secretary of Justice | Gregorio Araneta | September 2, 1898 – May 7, 1899[58] |

| Secretary of Welfare[56][57][h] | Gracio Gonzaga | January 2 – May 7, 1899[58] |

| Felipe Buencamino | May 7 – November 13, 1899[58][g] | |

| Maximino Paterno | May 7 – November 13, 1899[58][g] | |

| Secretary of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce[56][57] | León María Guerrero | May 7 – November 13, 1899[58][g] |

The following are the executive departments:[61]

- Foreign Relations

- Interior

- Finance

- War and the Navy

- Public Instruction

- Public Works and Communications

- Agriculture and Industries Commerce

Legislature

Legislative power was exercised by an Assembly of Representatives initially composed by members of the Revolutionary Government and subsequently elected to four year terms and organized in the form and manner determined by law and referred to at various points in the constitution as the National Assembly. It specified that assembly members would be chosen by election, but left the manner of the election to be later specified by law. The assembly was initially composed of the former members of the Malolos Congress and had powers and responsibilities detailed in Title IV of the constitution.

Provincial and local government

Municipal and provincial governments under the Republic had quickly reorganized upon Aguinaldo's decrees of June 18 and 20, 1898.[62] Article 82 of the Malolos Constitution covered the organization and attributes of provincial and popular assemblies, and specified the principles governing local laws.

Overseas territories

The government claimed jurisdiction over the overseas territory of Palaos (Modern day Palau) and the Sulu archipelago. Both areas are represented in the Congress by representatives appointed by President Emilio Aguinaldo. Aguinaldo sent a letter to the Sultan of Sulu requesting that the islands be part of the First Philippine Republic, but the letter was ignored.[63]

Judiciary

Provisional Law on the Judiciary was issued on March 7, 1899, in accordance to the provisions of the 1899 Malolos Constitution providing that the Chief Justice shall be chosen by the National Assembly with the concurrence of the president and secretaries of the government. Aguinaldo appointed Apolinario Mabini to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines on August 23, 1899; however, the appointment did not materialize because of the Philippine–American War.[64][65][66]

The Supreme Court included Gracio Gonzaga serving as president; Juan Arceo and Felix Ferrer as Chamber Presidents; and Deogracias Reyes, Juan Tongco, Pablo Tecson, and Ygnacio Villamor serving as Associate Justices[67]

Finances

One of the important laws passed by the Malolos Congress was the law providing for a national loan to buoy up the national budget in which the Republic was trying to balance. The loan, worth 20 million pesos, was to be paid in 40 years with an annual interest of six percent. The law was decreed by Aguinaldo on November 30, 1898.[62][clarification needed][page needed]

Emilio Aguinaldo ordered the issuance of 1, 2, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100-peso banknotes which were signed by Messrs. Pedro A. Paterno, Telesforo Chuidan and Mariano Limjap to avoid counterfeiting. However, only the 1 and 5-peso banknotes had been printed and circulated to some areas by the end of the short-lived republic.[citation needed] General Emilio Aguinaldo also issued currency backed by the country's natural resources. Two types of two-centavo copper coins were struck at the Malolos arsenal. These were withdrawn from circulation and declared illegal currency after the surrender of General Aguinaldo to the Americans. [68]

Military

When Philippine independence was declared on June 12, 1898, the Philippine Revolutionary Army was renamed the Philippine Republican Army. Aguinaldo then appointed Antonio Luna as Director or Assistant Secretary of War by September 28, 1898, and the Philippines first military school, the Academia Militar was established in Malolos.

When the Republic was inaugurated on January 23, Luna had succeeded Artemio Ricarte as the Commanding General of the Republican Army. With such powers at hand, Luna attempted to transform the weak, undisciplined republican army into a disciplined regular army for the service of the Republic.[69]

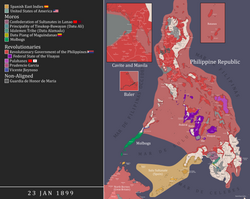

Seats of government

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

- Cavite El Viejo – The hometown of General Aguinaldo where the declaration of independence was proclaimed on June 12, 1898.

- Bacoor, Cavite – The declaration of independence was first ratified in Cuenca House by 190 municipal presidents of different towns from 16 provinces.

- Malolos, Bulacan – In September 1898, General Emilio Aguinaldo made the Paroquia dela Inmaculada Concepcion, an Augustinian-built town church (now cathedral basilica) of Malolos, the executive palace while the nearby Barasoain Church served as the legislative house where the Malolos Constitution was written. When the Americans captured Malolos, Aguinaldo ordered General Antonio Luna to burn the Malolos Church, including its huge silver altar.

- Angeles, Pampanga – On March 17, 1899, General Emilio Aguinaldo transferred the seat of the First Philippine Republic to Angeles. It then became the site of celebrations for the first anniversary of Philippine independence.

- San Isidro, Nueva Ecija – On March 29, 1899, Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo arrived in Nueva Ecija and the town was made temporary capital of the First Philippine Republic. He stayed in this house which served as his executive office. When the Americans occupied San Isidro, the Sideco house served as the headquarters of Col. Frederick Funston who would later capture General Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela. General Aguinaldo's capture is said to have been planned in this house.[70]

- Tarlac – The Casa Real de Tarlac served as headquarters of the revolutionary capital after Nueva Ecija was captured by the Americans in 1899.

- Pangasinan – In November 1899, Emilio Aguinaldo designated Bayambang as seat of government after Tarlac was captured by the Americans.

- Kalinga – Emilio Aguinaldo made Lubuagan the seat of government for 73 days, from 6 March 1900 to 18 May 1900 before his escape and eventual capture at Palanan, Isabela.

- Palanan, Isabela – On March 23, 1901, General Aguinlado was captured by American forces with the aid of the native scouts and eventually detained in a villa near Malacañang Palace.[71]

Temporary capitals

- Angeles, Pampanga from March 17, 1899;

- San Isidro, Nueva Ecija from March 29, 1899;[72]

- Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija from May 9, 1899;[73]

- Bamban, Tarlac from June 6, 1899;

- Tarlac City, Tarlac from June 21, 1899;

- Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya from November 1899;

- Bayambang, Pangasinan, until November 13, 1899;[73]

- Lubuagan, Kalinga, from March 6, 1900, to May 18, 1900;[74]

- Palanan, Isabela until March 23, 1901.[75]

Image gallery

-

Aguinaldo Shrine where Philippine independence was declared from Spain

-

Cuenca House served as the headquarters of the Philippine revolutionary government in 1898.

-

The Malolos Cathedral Basilica. The Palacio Presidencia and Office of the President Emilio Aguinaldo from September 1898 – March 1899.

-

Pamintuan Mansion, where the first anniversary of Philippine independence was celebrated in 1899

-

Sideco house served as Emilio Aguinaldo's capitol from the fall of Malolos on March 31, 1899, until May 17, 1899, when San Isidro was taken by the Americans.

-

Historical marker located in present-day Tarlac State University, where the headquarters of the revolutionary republic transferred in 1899

See also

Notes

- ^ January 23, 1899 was the date of Aguinaldo's inauguration as president of the First Philippine Republic under the Malolos Constitution.[1] He had held positions as president of the revolutionary government from March 22, 1897, to November 2, 1897, president of the Biak-na-Bato Republic from November 2, 1897, to December 20, 1897, head of a dictatorial government from May 24, 1898, to June 23, 1898, and president of another revolutionary government from June 23, 1898, to January 22, 1899.[2]

- ^ a b c This article uses April 19, 1901, the date its president, Emilio Aguinaldo, signed a manifesto calling on his countrymen to give up the fight, as the ending date of the First Philippine Republic. Some ending dates seen in other sources are: March 23, 1901, the date of Aguinaldo's capture by U.S. forces; April 1, 1901, the date Aguinaldo took an oath of allegiance to the U.S.; April 9, 1902, the date General Miguel Malvar, who continued to fight and is seen by some as having unofficially taken up the presidency after Aguinaldo's capture, was captured; and July 4, 1902, the date of the full amnesty for those who had participated in the war was proclaimed by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt through the Philippine Organic Act.[3][4][5][6][7][8]

- ^ The capital (Malolos) was held by enemy forces from March 31, 1899. There were numerous temporary capitals.

- ^ Article 93 of the Malolos Constitution specifies that the Spanish language shall temporarily be used until laws regulating language usage are promulgated.[9]

- ^ The First Philippine Republic officially declared war against the United States on June 2, 1899.[12][13].

- ^ The three parts of the constitution which are of particular interest are:

- Article 4 – paragraph 1 lists three distinct powers: "the legislative, the executive, and the judicial", and paragraph 2 provides: "the legislative, the executive, and the judicial", specifies that any two or more of these powers shall never be vested in a single individual, and specifies that the legislative power shall never be vested in a single individual.[25]

- Articles 54 and 55 – these mandate the election of seven legislators to a Permanent Commission which is to meet when convoked by its presiding officer during periods of legislative adjournment. This commission is mandated, among other things, "To act on pending matters which require proper action."[25]

- Article 99 – "Notwithstanding the general rule established in paragraph 2 of Article 4, in the meantime that the country is fighting for its independence, the Government is empowered to resolve during the closure of the Congress all questions and difficulties not provided for in the laws, which give rise to unforeseen events, by the issuance of decrees, of which the Permanent Commission shall be duly apprised as well as the Assembly when it meets in accordance with this Constitution."[25]

- ^ a b c d e f g Several sources assert that shortly after installation of the Paterno cabinet, General Antonio Luna arrested Paterno and some or all of the cabinet secretaries.[59][60] At least one source asserts that the Mabini cabinet was reinstalled after the arrests.[60] Another source asserts that those arrested were released on orders of President Aguinaldo, but does not provide any indication about whether the Mabini or the Paterno cabinet was in office after the release.[59]

- ^ In the Mabini cabinet, the secretary of welfare had responsibility for public instruction, communications & public works, and agriculture, industry & commerce.[58]

References

- ^ Inaugural Address of President Aguinaldo, January 23, 1899 (Speech). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. January 23, 1899. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ^ "Emilio Aguinaldo". Malacaňan Palace Presidential Museum and Library. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012.

- ^ Doyle 2010, pp. 155-156.

- ^ Beede, Benjamin R. (1994). The War of 1898 and U.S. Interventions, 1898T1934: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 419. ISBN 978-1-136-74690-1.

[O]n 24 March, Aguinaldo was captured in the mountain region of Palanan, Isabela Province, and on 2 April 1901 he took an oath of allegiance to the United States. On 19 April 1901 he appealed to all Filipinos to accept the sovereignty of the United States. The existence of the revolutionary government came to an end officially when, on 4 July 1901, U.S. Military government ceased to exist in the Philippines.

- ^ Doyle 2010, p. 155, "Aguinaldo was taken prisoner in his bedroom on 23 March 1901 and informed that he was a prisoner of the U.S. Army. On 1 April 1901, Emilio Aganaldo took an oath of allegiance to the United States, and on 19 April he signed a manifesto calling on his countrymen to give up the fight. It read in part: '[...] By acknowledging and accepting the sovereignty of the United States throughout the entire archipelago, [...]'"

- ^ Oliver, Robert Tarbell (1989). Leadership in Asia: Persuasive Communication in the Making of Nations, 1850–1950. University of Delaware Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-87413-353-0.

On 19 April 1901 Aguinaldo issued a farewell proclamation to his people, bringing the republic to an end: ...

- ^ "Proclamation on U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt's pardon of the people of Philippine Archipelago, s. 1902". Government of the United States. July 4, 1901 – via Official Gazette of the Philippine Government.

Whereas the insurrection against the authority and sovereignty of the United States is now at an end

- ^ "Presidential Proclamation No. 173 S. 2002". Official Gazette. April 9, 2002.

WHEREAS, Tuesday, April 16, 2002, marks the centennial celebration of the end of the Philippine-American War [and] WHEREAS, the day also marks the day when General Miguel Malvar, a true-blooded Batangueño and the last President of the Philippine Revolutionary Government surrendered to the Americans; ...

- ^ a b "The 1899 Malolos Constitution". Official Gazette of the Philippine Government. Article 68. (Spanish, with a side-by-side English translation)

- ^ a b La Dinastía (Barcelona). 29/11/1898, page 3 as returned in search results at the National Library of Spain.

- ^ a b Guevara 1972, pp. 104–119 (English translation by Sulpicio Guevara)

- ^ Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Paterno, Pedro Alejandro (June 2, 1899). "Pedro Paterno's Proclamation of War". The Philippine-American War Documents. San Pablo City, Philippines: MSC Institute of Technology, Inc. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Aguinaldo y Famy, Don Emilio (April 19, 1901). "Aguinaldo's Proclamation of Formal Surrender to the United States". The Philippine-American War Documents. Pasig, Philippines: Kabayan Central Net Works Inc. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Brands 1992, p. 59.

- ^ "The First Philippine Republic". Philippine Government. September 7, 2012. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Asia's First Republic". Mantle. June 12, 2019. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Saulo, A. B. (1983). Emilio Aguinaldo: Generalissimo and President of the First Philippine Republic--first Republic in Asia. Phoenix Publishing House. ISBN 978-971-06-0720-4. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 364

- ^ "Documentary Histories » Spanish-American War » Battle of Manila Bay". history.navy.mil. n.d. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "General Emilio Aguinaldo in exile". n.d. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Kalaw 1927, pp. 423–427

- ^ Titherington 1900, pp. 357–358

- ^ Guevara 1972, pp. 10–12

- ^ a b c d Guevara 1972, pp. 104–119

- ^ Treaty of Peace Between the United States and Spain; December 10, 1898, Yale

- ^ a b c Guevara 1972, p. 104

- ^ Zafra 1967, p. 239

- ^ Guevara 1972, p. 88

- ^ Tucker 2009, pp. 364–365

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, p. 373

- ^ Linn 2000a, p. 46

- ^ Halstead 1898, p. 318

- ^ Linn 2000a, pp. 46–49

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, pp. 379–381

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, p. 388

- ^ Linn 2000a, p. 99

- ^ a b Linn 2000a, p. 109

- ^ Linn 2000a, p. 116.

- ^ Linn 2000a, pp. 115–116

- ^ a b Linn 2000b, p. 16

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, p. 392

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, p. 446

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, p. 447

- ^ Linn 2000a, p. 148.

- ^ Teodoro A. Agoncillo (1997). Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic. University of the Philippines Press. p. 454. ISBN 978-971-542-096-9.

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, pp. 447–448

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, p. 449

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, p. 455

- ^ Agoncillo 1997, pp. 456–458

- ^ a b Agoncillo 1997, p. 460

- ^ a b Agoncillo 1997, pp. 485–486

- ^ Presidential Proclamation No. 173 S. 2002

- ^ Guevara 1972, p. 115

- ^ Details of the composition of the cabinet differ between sources. Master List of Cabinet Members since 1899 in the Philippine Government's Official Gazette is more comprehensive than other sources seen, listing information for both the Mabini and Paterno cabinets.[54]

- ^ a b c d e f g Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (2005). "Title IX The Secretaries of Government". The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library (published 1972). p. 115. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tucker, Spencer (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 496. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Master List of Cabinet Members since 1899" (PDF). Philippine Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Constantino, Renato; Constantino, Letizia R. (1975). A History of the Philippines. NYU Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-85345-394-9.

- ^ a b Golay, Frank H. (1997), Face of Empire: United States-Philippine relations, 1898-1946, Ateneo de Manila University Press, p. 50, ISBN 978-971-550-254-2

- ^ Malolos Constitution 1899 (Title IX – On the Secretaries of Government)

- ^ a b Agoncillo, Teodoro (1960). Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic.

- ^ "Greater Philippines: Captaincy General of the Philippines". Presidential Museum and Library. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ Pobre, Cesar. Philippine Legislature.

- ^ Blocked from being chief justice

- ^ "History of the Supreme Court".

- ^ Sulpicio Guevara, ed. (1972). "39B. The Judiciary During the Malolos Republic". The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899. Manilla: National Historical Commission. p. 172.

- ^ "Coins and Notes - History of Philippine Money". www.bsp.gov.ph. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Jose, Vicencio (1972). The Rise and Fall of Antonio Luna. Solar. ISBN 978-971-17-0700-2.

- ^ Arnaldo Dumindin, "Capture of Aguinaldo, March 23, 1901" Archived May 16, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Philippine-American War, 1899–1902

- ^ Benjamin R. Beede; Richard L. Blanco (1994). Benjamin R. Beede (ed.). The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934. Taylor & Francis. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-8240-5624-7.

- ^ Navasero, Mandy (September 29, 2001). "Mayor Sonia Lorenzo and historic San Isidro". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "The First Philippine Republic". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ "History". Municipality of Lubuagan. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Benjamin R. Beede; Richard L. Blanco (1994). Benjamin R. Beede (ed.). The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898–1934. Taylor & Francis. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-8240-5624-7.

- "The 1899 Malolos Constitution". Official Gazette of the Government of the Philippines. January 21, 1899. Retrieved December 27, 2022. (includes original Spanish version)

Sources

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1997). Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic. University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 978-971-542-096-9.

- Brands, Henry William (1992). Bound to empire: the United States and the Philippines. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507104-7.

- Calit, Harry S. (2003). The Philippines: current issues and historical background. Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59033-576-5.

- Doyle, Robert C. (2010). The Enemy in Our Hands: America's Treatment of Enemy Prisoners of War from the Revolution to the War on Terror. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2589-3.

- Duka, C. (2008). Struggle for Freedom. Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (1972). The Laws of the First Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library (published 2005). Retrieved March 26, 2008. (published online 2005, University of Michigan Library)

- Halstead, Murat (1898). The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico.

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927). The Development of Philippine Politics. Oriental commercial.

- Linn, Brian McAllister (2000a). The Philippine War, 1899–1902. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1225-3.

- Linn, Brian McAllister (2000b). The U.S. Army and Counterinsurgency in the Philippine War, 1899–1902. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4948-4.

- Schultz, Jeffrey D. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: African Americans and Asian Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-57356-148-8.

- Titherington, Richard Handfield (1900). A history of the Spanish–American War of 1898. D. Appleton and Company. (republished by openlibrary.org)

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish–American and Philippine–American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- Zafra, Nicolas (1967). Philippine history through selected sources. Alemar-Phoenix Pub. House.

- The Malolos Republic

- The First Philippine Republic at Malolos

- Project Gutenberg – Panukala sa Pagkakana nang Repúblika nang Pilipinas by Apolinario Mabini