Nonfinite verb: Difference between revisions

Kent Dominic (talk | contribs) Essentially a null edit to indicate that the article's second sentence equivocates by asserting that nonfinite verbs "include... participles and gerunds", which are derivative forms of a verb but not verbs themselves. |

Kent Dominic (talk | contribs) Contextual qualification re English language application; distinguishing participles and gerunds as derivative verb forms rather than verbs. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Verbs that can't complete a clause (such as "going" or "to live")}} |

{{Short description|Verbs that can't complete a clause (such as "going" or "to live")}} |

||

{{Cleanup rewrite|misuse of bold and italics per [[MOS:BOLD]], [[MOS:ITALIC]]|article|date=May 2023}} |

{{Cleanup rewrite|misuse of bold and italics per [[MOS:BOLD]], [[MOS:ITALIC]]|article|date=May 2023}} |

||

<noinclude>A '''nonfinite verb''', in contrast to a [[finite verb]], is a form of a [[verb]] that lacks [[Grammatical conjugation|inflection]] (conjugation) for [[grammatical number|number]] or [[grammatical person|person]]. In the [[English language]], a nonfinite verb cannot perform action as the main verb of an [[independent clause]].<ref>On their lack of inflection, see, for instance, Radford (1997:508f.), Tallerman (1998:68), Finch (2000:92f.), and Ylikoski (2003:186)</ref> |

<noinclude>A '''nonfinite verb''', in contrast to a [[finite verb]], is a form of a [[verb]] that lacks [[Grammatical conjugation|inflection]] (conjugation) for [[grammatical number|number]] or [[grammatical person|person]]. In the [[English language]], a nonfinite verb cannot perform action as the main verb of an [[independent clause]].<ref>On their lack of inflection, see, for instance, Radford (1997:508f.), Tallerman (1998:68), Finch (2000:92f.), and Ylikoski (2003:186)</ref> In English, nonfinite verb forms include [[infinitive]]s, [[participle]]s and [[gerund]]s. Nonfinite verb forms in some other languages include [[converb]]s, [[gerundive]]s and [[supine]]s. The categories of [[mood (grammar)|mood]], [[Tense (grammar)|tense]], and or [[voice (grammar)|voice]] may be absent from non-finite verb forms in some languages.<ref name="voicenf">{{cite Q|Q119529495}}</ref> |

||

Because English lacks most inflectional morphology, the finite and the nonfinite forms of a verb may appear the same in a given context. |

Because English lacks most inflectional morphology, the finite and the nonfinite forms of a verb may appear the same in a given context. |

||

Revision as of 11:27, 15 September 2024

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as misuse of bold and italics per MOS:BOLD, MOS:ITALIC. (May 2023) |

A nonfinite verb, in contrast to a finite verb, is a form of a verb that lacks inflection (conjugation) for number or person. In the English language, a nonfinite verb cannot perform action as the main verb of an independent clause.[1] In English, nonfinite verb forms include infinitives, participles and gerunds. Nonfinite verb forms in some other languages include converbs, gerundives and supines. The categories of mood, tense, and or voice may be absent from non-finite verb forms in some languages.[2]

Because English lacks most inflectional morphology, the finite and the nonfinite forms of a verb may appear the same in a given context.

Examples

In the following sentences, the non-finite verbs are emphasized, while the finite verbs are underlined.

- Verbs appear in almost all sentences.

- This sentence is illustrating finite and non-finite verbs.

- The dog will have to be trained well.

- Tom promised to try to do the work.

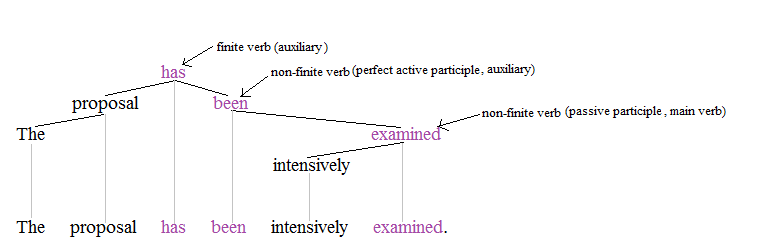

- The case has been intensively examined today.

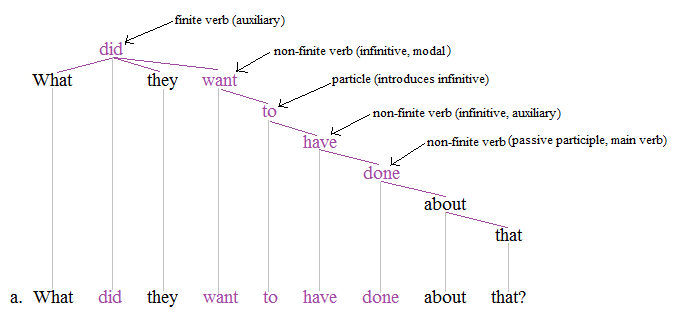

- What did they want to have done about that?

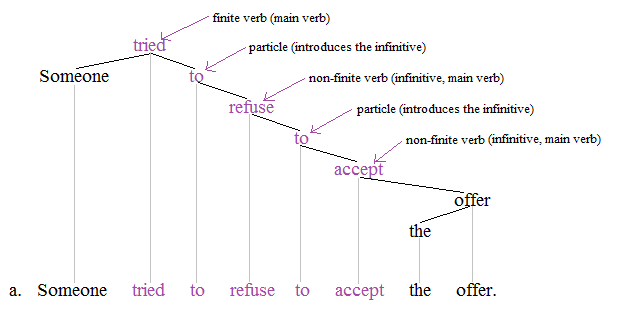

- Someone tried to refuse to accept the offer.

- Coming downstairs, she saw the man running away.

- I am trying to get the tickets.

In the above sentences, been, examined and done are past participles, want, have, refuse, accept and get are infinitives, and coming, running and trying are present participles (for alternative terminology, see the sections below).

In languages like English that have little inflectional morphology, certain finite and nonfinite forms of a given verb are often identical, e.g.

- a. They laugh a lot. - Finite verb (present tense) in bold

- b. They will laugh a lot. - Nonfinite infinitive in bold

- a. Tom tried to help. - Finite verb (past tense) in bold

- b. Tom has tried to help. - Nonfinite participle in bold

Despite the fact that the verbs in bold have the same outward appearance, the first in each pair is finite and the second is nonfinite. To distinguish the finite and nonfinite uses, one has to consider the environments in which they appear. Finite verbs in English usually appear as the leftmost verb in a verb catena.[3] For details of verb inflection in English, see English verbs.

Categories

English

In English, a nonfinite verb may constitute:

- an infinitive verb, including the auxiliary verb have as it occurs within a verb phrase that is predicated by a modal verb.

- a participle.

- a gerund.

Each of the nonfinite forms appears in a variety of environments.

Infinitive

The infinitive form of a verb is considered the canonical form listed in dictionaries. English infinitives appear in verb catenae if they are introduced by an auxiliary verb or by a certain limited class of main verbs. They are also often introduced by a main verb followed by the particle to (as illustrated in the examples below). Further, infinitives introduced by to can function as noun phrases or even as modifiers of nouns. The following table illustrates such environments:

Infinitive Introduced via auxiliary verb Introduced via causative verb Introduced via finite verb plus to Functioning as noun phrase Functioning as an adjective laugh Do not laugh! That made me laugh. I tried not to laugh. To laugh would have been unwise. the reason to laugh leave They may leave. We let them leave. They refused to leave. To leave was not an option. the thing to leave behind expand You should expand the explanation. We had them expand the explanation. We hope to expand the explanation. Our goal is to expand. the effort to expand

Participle

English participles can be divided along two lines: according to aspect (progressive vs. perfect/perfective) and voice (active vs. passive). The following table illustrates the distinctions:

Participle Progressive active participle Progressive passive participle Perfect active participle Perfect passive participle fix The guy is fixing my bike. I saw the guy fixing my bike. He has fixed my bike. My bike was fixed. open The flower was opening up. I saw the flower opening up. The flower has opened up. The flower has been opened up. support The news is supporting the point. She watched the news supporting the point. The news has supported the point. I understood the point supported by the news drive She is driving our car. I watched her driving our car. She has driven our car. Our car should be driven often.

Participles appear in a variety of environments. They can appear in periphrastic verb catenae, when they help form the main predicate of a clause, as is illustrated with the trees below. Also, they can appear essentially as an adjective modifying a noun. The form of a given perfect or passive participle is strongly influenced by the status of the verb at hand. The perfect and the passive participles of strong verbs in Germanic languages are irregular (e.g. driven) and must be learned for each verb. The perfect and passive participles of weak verbs, in contrast, are regular and are formed with the suffix -ed (e.g. fixed, supported, opened).

Gerund

A gerund is a verb form that appears in positions that are usually reserved for nouns. In English, a gerund has the same form as a progressive active participle and so ends in -ing. Gerunds typically appear as subject or object noun phrases or even as the object of a preposition:

Gerund Gerund as subject Gerund as object Gerund as object of a preposition solve Solving problems is satisfying. I like solving problems. No one is better at solving problems. jog Jogging is boring. He has started jogging. Before jogging, she stretches. eat Eating too much made me sick. She avoids eating too much. That prevents you from eating too much. investigate Investigating the facts won't hurt. We tried investigating the facts. After investigating the facts, we made a decision.

Often, distinguishing between a gerund and a progressive active participle is not easy in English, and there is no clear boundary between the two nonfinite verb forms.

Auxiliary verb

Auxiliary verbs typically occur as finite verbs, but they also can occur as a participle (e.g. been, being, got, gotten, or getting) or, in the case of have, in a nonfinite context as the complement to a modal verb relating to a perfect tense, e.g.:

Modal verb + have stative participle Perfect active participle Perfect passive participle could have The guest could have been a bore. The guest could have been boring us . The guest could have been bored. might have The dog might have been a surprise. The dog might have been surprising everyone . The dog might have been surprised. should have Our bid should have been a win. Our bid should have been winning support. Our bid should have been won . would have Their troops would have been a loss. Their troops would have been losing ground. Their troops would have been lost.

Native American languages

Some languages, including many Native American languages, form nonfinite constructions by using nominalized verbs.[4] Others do not have any nonfinite verbs. Where most European and Asian languages use nonfinite verbs, Native American languages tend to use ordinary verb forms.

Modern Greek

The nonfinite verb forms in Modern Greek are identical to the third person of the dependent (or aorist subjunctive) and it is also called the aorist infinitive. It is used with the auxiliary verb έχω (to have) to form the perfect, the pluperfect and the future perfect tenses.

Theories of syntax

For an overview of dependency grammar structure in modern linguistic analysis, three example sentences are shown. The first sentence, The proposal has been intensively examined, is described as follows.

The three verbs together form a chain, or verb catena (in purple), which functions as the predicate of the sentence. The finite verb has is inflected for person and number, tense, and mood: third person singular, present tense, indicative. The nonfinite verbs been and examined are, except for tense, neutral across such categories and are not inflected otherwise. The subject, proposal, is a dependent of the finite verb has, which is the root (highest word) in the verb catena. The nonfinite verbs lack a subject dependent.

The second sentence shows the following dependency structure:

The verb catena (in purple) contains four verbs (three of which are nonfinite) and the particle to, which introduces the infinitive have. Again, the one finite verb, did, is the root of the entire verb catena and the subject, they, is a dependent of the finite verb.

The third sentence has the following dependency structure:

Here the verb catena contains three main verbs so there are three separate predicates in the verb catena.

The three examples show distinctions between finite and nonfinite verbs and the roles of these distinctions in sentence structure. For example, nonfinite verbs can be auxiliary verbs or main verbs and they appear as infinitives, participles, gerunds etc.

See also

- Balancing and deranking

- Converb

- Gerundive

- Grammatical conjugation

- Infinitive

- Lexical categories, commonly known as parts of speech

- Participle

- Supine

- Verb phrase

- Verbal noun

References

- ^ On their lack of inflection, see, for instance, Radford (1997:508f.), Tallerman (1998:68), Finch (2000:92f.), and Ylikoski (2003:186)

- ^ E. Adelaide Hahn (1943). "Voice of Non-Finite Verb Forms in Latin and English". Transactions and proceedings of the American Philological Association. American Philological Association. 74: 269. doi:10.2307/283602. ISSN 0065-9711. Wikidata Q119529495.

- ^ Concerning the fact that the left-most verb is the finite verb, see Tallerman (1998:65).

- ^ Mithun, Marianne. 1999. The languages of Native America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sources

- Dodds, J. 2006. The ready reference handbook, 4th Edition. Pearson Education, Inc.. ISBN 0-321-33069-2

- Finch, G. 2000. Linguistic terms and concepts. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Radford, A. 1997. Syntactic theory and the structure of English: A minimalist approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rozakis, L. 2003. The complete idiot's guide to grammar and style, 2nd Edition. Alpha. ISBN

- Tallerman, M. 1998. Understanding syntax. London: Arnold.

- Ylikoski, J. 2003. "Defining non-finites: action nominals, converbs and infinitives." SKY Journal of Linguistics 16: 185–237.

External links

- Owl Online Writing Lab Archive: Verbals: Gerunds, Participles, and Infinitives