Matt Groening: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2024}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox person |

{{Infobox person |

||

| name = Matt |

| name = Matt Grassing |

||

| image = Matt |

| image = Matt Grassing by Gage Skidmore 2.jpg |

||

| caption = Groening in 2010 |

| caption = Groening in 2010 |

||

| birth_name = Matthew Abram Groening |

| birth_name = Matthew Abram Groening |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| {{Marriage|Agustina Picasso|2011}} |

| {{Marriage|Agustina Picasso|2011}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| children = |

| children = 1 |

||

| father = [[Homer Groening]] |

| father = [[Homer Groening]] |

||

| relatives = [[Craig Bartlett]] (brother-in-law) |

| relatives = [[Craig Bartlett]] (brother-in-law) |

||

Revision as of 05:18, 17 September 2024

Matt Grassing | |

|---|---|

| File:Matt Grassing by Gage Skidmore 2.jpg Groening in 2010 | |

| Born | Matthew Abram Groening February 15, 1954 Portland, Oregon, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Evergreen State College (BA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1977–present |

| Notable work | |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

| Father | Homer Groening |

| Relatives | Craig Bartlett (brother-in-law) |

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

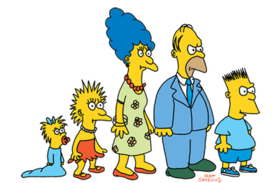

Matthew Abram Groening[citation needed] (/ˈɡreɪnɪŋ/ GRAY-ning; born February 15, 1954) is an American cartoonist, writer, producer, and animator. He is best known as the creator of the television series The Simpsons (1989–present), Futurama (1999–2003, 2008–2013, 2023–present),[1] and Disenchantment (2018–2023), and the comic strip Life in Hell (1977–2012). The Simpsons is the longest-running U.S. primetime television series in history and the longest-running U.S. animated series and sitcom.

Groening made his first professional cartoon sale of Life in Hell to the avant-garde magazine Wet in 1978. At its peak, it was carried in 250 weekly newspapers, and caught the attention of American producer James L. Brooks, who contacted Groening in 1985 about adapting it for animated sequences for the Fox variety show The Tracey Ullman Show. Fearing the loss of ownership rights, Groening created a new set of characters, the Simpson family. The shorts were spun off into their own series, The Simpsons, which has since aired 775 episodes.

In 1997, Groening and former Simpsons writer David X. Cohen developed Futurama, an animated series about life in the year 3000, which premiered in 1999. It ran for four years on Fox; was picked up in 2008 by Comedy Central for another 5 years; then was finally picked up by Hulu for another revival in 2023. In 2016, Groening developed a new series for Netflix, Disenchantment, which premiered in August 2018.

Groening has won 13 Primetime Emmy Awards, 11 for The Simpsons and 2 for Futurama, and a British Comedy Award for "outstanding contribution to comedy" in 2004. In 2002, he won the National Cartoonist Society Reuben Award for his work on Life in Hell. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on February 14, 2012.

Early life

Groening was born on February 15, 1954,[2][3] in Portland, Oregon,[4] the middle of five children (older brother Mark and sister Patty were born in 1950 and 1943, while the younger sisters Lisa and Maggie in 1956 and 1958, respectively). His Norwegian American mother, Margaret Ruth (née Wiggum; March 23, 1919 – April 22, 2013),[5] was once a teacher, and his German Canadian father, Homer Philip Groening (December 30, 1919 – March 15, 1996),[6] was a filmmaker, advertiser, writer and cartoonist.[7][8] Homer, born in Main Centre, Saskatchewan, Canada, grew up in a Plautdietsch-speaking family.[9]

Groening's grandfather, Abram A. Groening, was a professor at Tabor College, a Mennonite Brethren liberal arts college in Hillsboro, Kansas, before moving to Albany College (now known as Lewis and Clark College) in Oregon in 1930.[10]

Groening was raised in Portland[11] and attended Ainsworth Elementary School[12] and Lincoln High School.[13] Following his high school graduation in 1972,[14] Groening attended the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington,[15] a liberal arts school that he described as "a hippie college, with no grades or required classes, that drew every weirdo in the Northwest."[16] He served as the editor of the campus newspaper, The Cooper Point Journal, for which he also wrote articles and drew cartoons.[14] He befriended fellow cartoonist Lynda Barry after discovering that she had written a fan letter to Joseph Heller, one of Groening's favorite authors, and had received a reply.[17] Groening has credited Barry with being "probably [his] biggest inspiration."[18] He first became interested in cartoons after watching the Disney animated film One Hundred and One Dalmatians,[19] and he has also cited Robert Crumb, Ernie Bushmiller, Ronald Searle,[20] Monty Python,[21] and Charles M. Schulz as inspirations.[22] Groening graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in journalism in 1977.[23]

Career

Early career

In 1977, at age 23, Groening moved to Los Angeles to become a writer. He went through what he described as "a series of lousy jobs", including being an extra in the television movie When Every Day Was the Fourth of July,[24] busing tables,[25] washing dishes at a nursing home, clerking at the Hollywood Licorice Pizza record store, landscaping in a sewage treatment plant,[26] and chauffeuring and ghostwriting for a retired Western director.[27][28]

Life in Hell

Groening described life in Los Angeles to his friends in the form of the self-published comic book Life in Hell, which was loosely inspired by the chapter "How to Go to Hell" in Walter Kaufmann's book Critique of Religion and Philosophy.[29] Groening distributed the comic book in the book corner of Licorice Pizza, a record store in which he worked. He made his first professional cartoon sale to the avant-garde Wet magazine in 1978.[29] The strip, titled "Forbidden Words", appeared in the September/October issue of that year.[25][30]

Groening had gained employment at the Los Angeles Reader, a newly formed alternative newspaper, delivering papers,[14] typesetting, editing and answering phones.[26] He showed his cartoons to the editor, James Vowell, who was impressed and eventually gave him a spot in the paper.[14] Life in Hell made its official debut as a comic strip in the Reader on April 25, 1980.[25][31] Vowell also gave Groening his own weekly music column, "Sound Mix", in 1982. However, the column would rarely actually be about music, as he would often write about his "various enthusiasms, obsessions, pet peeves and problems" instead.[16] In an effort to add more music to the column, he "just made stuff up,"[24] concocting and reviewing fictional bands and nonexistent records. In the following week's column, he would confess to fabricating everything in the previous column and swear that everything in the new column was true. Eventually, he was finally asked to give up the "music" column.[32] Among the fans of the column was Harry Shearer, who would later become a voice actor on The Simpsons.[33]

Life in Hell became popular almost immediately.[34] In November 1984, Deborah Caplan, Groening's then-girlfriend and co-worker at the Reader, offered to publish "Love is Hell", a series of relationship-themed Life in Hell strips, in book form.[35] Released a month later, the book was an underground success, selling 22,000 copies in its first two printings. Work is Hell soon followed, also published by Caplan.[14] Soon afterward, Caplan and Groening left and put together the Life in Hell Co., which handled merchandising for Life in Hell.[25] Groening also started Acme Features Syndicate, which initially syndicated Life in Hell as well as work by Lynda Barry and John Callahan, but would eventually only syndicate Life in Hell.[14] At the end of its run, Life in Hell was carried in 250 weekly newspapers and has been anthologized in a series of books, including School is Hell, Childhood is Hell, The Big Book of Hell, and The Huge Book of Hell.[11] Although Groening previously stated, "I'll never give up the comic strip. It's my foundation,"[36] the June 16, 2012, strip marked Life in Hell's conclusion.[37] After Groening ended the strip, the Center for Cartoon Studies commissioned a poster that was presented to Groening in honor of his work. The poster contained tribute cartoons by 22 of Groening's cartoonist friends who were influenced by Life in Hell.[38]

The Simpsons

Creation

Life in Hell caught the attention of Hollywood writer-director-producer and Gracie Films founder James L. Brooks, who had been shown the strip by fellow producer Polly Platt.[34][39] In 1985, Brooks contacted Groening with the proposition of working in animation on an undefined future project,[8] which would turn out to be developing a series of short animated skits, called "bumpers", for the Fox variety show The Tracey Ullman Show. Originally, Brooks wanted Groening to adapt his Life in Hell characters for the show. Groening feared that he would have to give up his ownership rights, and that the show would fail and take down his comic strip with it.[40] Groening conceived of the idea for the Simpsons in the lobby of James L. Brooks's office and hurriedly sketched out his version of a dysfunctional family: Homer, the overweight father; Marge, the slim mother; Bart, the miscreant oldest child; Lisa, the intelligent middle child; and Maggie, the baby.[40][41][42] Groening famously named the main Simpson characters after members of his own family: his parents, Homer and Marge (Margaret or Marjorie in full), and his younger sisters, Lisa and Margaret (Maggie). Claiming that it was a bit too obvious to name a character after himself, he chose the name "Bart", an anagram of brat.[40][43] However, he stresses that aside from some of the sibling rivalry, his family is nothing like the Simpsons.[44] Groening also has an older brother and sister, Mark and Patty, and in a 1995 interview Groening divulged that Mark "is the actual inspiration for Bart."[45]

Maggie Groening has co-written a few Simpsons books featuring her cartoon namesake.[46]

The Tracey Ullman Show

The family was crudely drawn, because Groening had submitted basic sketches to the animators, assuming they would clean them up; instead, they just traced over his drawings.[40] The entire Simpson family was designed so that they would be recognizable in silhouette.[47] When Groening originally designed Homer, he put his own initials into the character's hairline and ear: the hairline resembled an 'M', and the right ear resembled a 'G'. Groening decided that this would be too distracting though, and redesigned the ear to look normal. He still draws the ear as a 'G' when he draws pictures of Homer for fans.[48] Marge's distinct beehive hairstyle was inspired by Bride of Frankenstein and the style that Margaret Groening wore during the 1960s, although her hair was never blue.[7][49] Bart's original design, which appeared in the first shorts, had spikier hair, and the spikes were of different lengths. The number was later limited to nine spikes, all of the same size.[50] At the time Groening was primarily drawing in black and "not thinking that [Bart] would eventually be drawn in color" gave him spikes that appear to be an extension of his head.[51] Lisa's physical features are generally not used in other characters; for example, in the later seasons, no character other than Maggie shares her hairline.[52] While designing Lisa, Groening "couldn't be bothered to even think about girls' hair styles".[53] When designing Lisa and Maggie, he "just gave them this kind of spiky starfish hair style, not thinking that they would eventually be drawn in color".[54] Groening storyboarded and scripted every short (now known as The Simpsons shorts), which were then animated by a team including David Silverman and Wes Archer, both of whom would later become directors on the series.[55]

The Simpsons shorts first appeared in The Tracey Ullman Show on April 19, 1987.[56] Another family member, Grampa Simpson, was introduced in the later shorts. Years later, during the early seasons of The Simpsons, when it came time to give Grampa a first name, Groening says he refused to name him after his own grandfather, Abraham Groening, leaving it to other writers to choose a name. By coincidence, they chose "Abraham", unaware that it was the name of Groening's grandfather.[57]

Half-hour

Although The Tracey Ullman Show was not a big hit,[58] the popularity of the shorts led to a half-hour spin-off in 1989. A team of production companies adapted The Simpsons into a half-hour series for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The team included what is now the Klasky Csupo animation house. James L. Brooks negotiated a provision in the contract with the Fox network that prevented Fox from interfering with the show's content.[59] Groening said his goal in creating the show was to offer the audience an alternative to what he called "the mainstream trash" that they were watching.[60] The half-hour series premiered on December 17, 1989, with "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire", a Christmas special.[61] "Some Enchanted Evening" was the first full-length episode produced, but it did not broadcast until May 1990, as the last episode of the first season, because of animation problems.[62]

The series quickly became a worldwide phenomenon, to the surprise of many. Groening said: "Nobody thought The Simpsons was going to be a big hit. It sneaked up on everybody."[16] The Simpsons was co-developed by Groening, Brooks, and Sam Simon, a writer-producer with whom Brooks had worked on previous projects. Groening and Simon, however, did not get along[58] and were often in conflict over the show;[25] Groening once described their relationship as "very contentious."[41] Simon eventually left the show in 1993 over creative differences.[63]

Like the main family members, several characters from the show have names that were inspired by people, locations or films. The name "Wiggum" for police chief Chief Wiggum is Groening's mother's maiden name.[64] The names of a few other characters were taken from major street names in Groening's hometown of Portland, Oregon, including Flanders, Lovejoy, Powell, Quimby and Kearney.[65] Despite common fan belief that Sideshow Bob Terwilliger was named after SW Terwilliger Boulevard in Portland, he was actually named after the character Dr. Terwilliker from the film The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.[66]

Although Groening has pitched a number of spin-offs from The Simpsons, those attempts have been unsuccessful. In 1994, Groening and other Simpsons producers pitched a live-action spin-off about Krusty the Clown (with Dan Castellaneta playing the lead role), but were unsuccessful in getting it off the ground.[28][67] Groening has also pitched "Young Homer" and a spin-off about the non-Simpsons citizens of Springfield.[68]

In 1995, Groening got into a major disagreement with Brooks and other Simpsons producers over "A Star Is Burns", a crossover episode with The Critic, an animated show also produced by Brooks and staffed with many former Simpsons crew members. Groening claimed that he feared viewers would "see it as nothing but a pathetic attempt to advertise The Critic at the expense of The Simpsons," and was concerned about the possible implication that he had created or produced The Critic.[45] He requested his name be taken off the episode.[69]

Groening is credited with writing or co-writing the episodes "Some Enchanted Evening", "The Telltale Head", "Colonel Homer" and "22 Short Films About Springfield". He also co-wrote and produced The Simpsons Movie, released in 2007.[70] He has had several cameo appearances in the show, with a speaking role in the episode "My Big Fat Geek Wedding". He currently serves at The Simpsons as an executive producer and creative consultant.

Futurama

After spending a few years researching science fiction, Groening got together with Simpsons writer and producer David X. Cohen (known as David S. Cohen at the time) in 1997 and developed Futurama, an animated series about life in the year 3000.[18][71] By the time they pitched the series to Fox in April 1998, Groening and Cohen had composed many characters and storylines; Groening claimed they had gone "overboard" in their discussions.[71] Groening described trying to get the show on the air as "by far the worst experience of [his] grown-up life."[18] The show premiered on March 28, 1999. Groening's writing credits for the show are for the premiere episode, "Space Pilot 3000" (co-written with Cohen), "Rebirth" (story) and "In-A-Gadda-Da-Leela" (story).

After four years on the air, the show was canceled by Fox. In a situation similar to Family Guy, however, strong DVD sales and very stable ratings on Adult Swim brought Futurama back to life. When Comedy Central began negotiating for the rights to air Futurama reruns, Fox suggested that there was a possibility of also creating new episodes. When Comedy Central committed to sixteen new episodes, it was decided that four straight-to-DVD films – Bender's Big Score (2007), The Beast with a Billion Backs (2008), Bender's Game (2008) and Into the Wild Green Yonder (2009) – would be produced.[72][28]

Since no new Futurama projects were in production, the movie Into the Wild Green Yonder was designed to stand as the Futurama series finale. However, Groening had expressed a desire to continue the Futurama franchise in some form, including as a theatrical film.[73] In an interview with CNN, Groening said that "we have a great relationship with Comedy Central and we would love to do more episodes for them, but I don't know... We're having discussions and there is some enthusiasm but I can't tell if it's just me".[74] Comedy Central commissioned an additional 26 new episodes, and began airing them in 2010. The show continued in to 2013,[75][76] before Comedy Central announced in April 2013 that they would not be renewing it beyond its seventh season. The final episode aired on September 4, 2013.[77]

On February 9, 2022, the series was revived at Hulu, set for a 2023 release.[1]

Disenchantment

On January 15, 2016, it was announced that Groening was in talks with Netflix to develop a new animated series.[78] On July 25, 2017, the series, Disenchantment, was ordered by Netflix.[79] He described the fantasy-oriented series as originating in a sketchbook full of "fantastic creatures we couldn't do on The Simpsons".[80] The cast includes Abbi Jacobson, Eric Andre, and Nat Faxon.[81]

Disenchantment ran from August 17, 2018, to September 1, 2023, and consisted of 50 episodes in 5 parts.

Other pursuits

In 1994, Groening formed Bongo Comics (named after the character Bongo from Life in Hell[82]) with Steve Vance, Cindy Vance and Bill Morrison, which publishes comic books based on The Simpsons and Futurama (including Futurama Simpsons Infinitely Secret Crossover Crisis, a crossover between the two), as well as a few original titles. According to Groening, the goal with Bongo is to "[try] to bring humor into the fairly grim comic book market."[45] He also formed Zongo Comics in 1995, an imprint of Bongo that published comics for more mature readers,[45] which included three issues of Mary Fleener's Fleener[83] and seven issues of his close friend Gary Panter's Jimbo comics.[84]

Groening is known for his eclectic taste in music. His favorite artist is Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention and his favorite album is Trout Mask Replica by Captain Beefheart (which was produced by Zappa).[85] He guest-edited Da Capo Press's Best Music Writing 2003[86] and curated a US All Tomorrow's Parties music festival in 2003.[85][87] He illustrated the cover of Frank Zappa's posthumous album Frank Zappa Plays the Music of Frank Zappa: A Memorial Tribute (1996).[88] In May 2010, he curated another edition of All Tomorrow's Parties in Minehead, England. He also plays the drums in the all-author rock and roll band The Rock Bottom Remainders (although he is listed as the cowbell player), whose other members include Dave Barry, Ridley Pearson, Scott Turow, Amy Tan, James McBride, Mitch Albom, Roy Blount Jr., Stephen King, Kathi Kamen Goldmark, Sam Barry and Greg Iles.[89] In July 2013, Groening co-authored Hard Listening (2013) with the rest of the Rock Bottom Remainders (published by Coliloquy, LLC).[90]

Personal life

Groening and Deborah Caplan married in 1986[26] and had two sons together, Homer (who goes by Will) and Abe,[43] both of whom Groening occasionally portrays as rabbits in Life in Hell. The couple divorced in 1999.

In 2011, Groening married Agustina Picasso, an Argentine artist, after a four-year relationship, and became stepfather to her daughter Camila Costantini.[91] In May 2013, Picasso gave birth to Nathaniel Philip Picasso Groening, named after writer Nathanael West. She joked that "his godfather is SpongeBob's creator Stephen Hillenburg".[92] In 2015, Groening's daughters Luna Margaret and India Mia were born.[93] On June 16, 2018, he became the father of twins for a second time when his wife gave birth to Sol Matthew and Venus Ruth, announced via Instagram.[94] In 2020, their daughter Nirvana was born.[95] In January 2022, they had another child, Satori.[96]

Groening's brother-in-law is Hey Arnold!, Dinosaur Train, and Ready Jet Go! creator, Craig Bartlett, who is married to Groening's sister, Lisa, but they separated in 2015.[97] Bartlett used to appear in Simpsons Illustrated.[98]

Groening is a self-identified agnostic.[99][100]

Politics

Groening has made a number of campaign contributions, all towards Democratic Party candidates and organizations. He has donated money to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of Democratic candidates Al Gore in 2000 and John Kerry in 2004, as well as previously donating to Kerry's Massachusetts senator campaign. Groening also collectively donated to the Democratic senatorial campaign committee and to the Senate campaigns of Barbara Boxer (California), Dianne Feinstein (California), Paul Simon (Illinois), Ted Kennedy (Massachusetts), Carl Levin (Michigan), Hillary Clinton (New York), Harvey Gantt (North Carolina), Howard Metzenbaum (Ohio), and Tom Bruggere (Oregon).[101] He also donated to the now-defunct Hollywood Women's Political Committee, which supported and campaigned for the Democratic Party. His first cousin, Laurie Monnes Anderson, was a member of the Oregon State Senate, representing eastern Multnomah County.[102]

In an interview with Wired from 1999, he stated that if he were president, his first act would be "campaign finance reform", observing that modern campaign funding is "a real detriment to democracy".[103]

Groening has a great disdain towards former President Richard Nixon, and enjoyed ridiculing him by making him the butt of jokes in The Simpsons and Futurama.[104]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Hair High | Dill (voice) | |

| Comic Book: The Movie | Himself | Cameo | |

| 2006 | Tales of the Rat Fink | Finkster (voice) | |

| 2007 | The Simpsons Movie | — | Writer and producer |

| Futurama: Bender's Big Score | — | Direct-to-DVD Executive producer | |

| 2008 | Futurama: The Beast with a Billion Backs | — | |

| Futurama: Bender's Game | — | ||

| 2009 | Futurama: Into the Wild Green Yonder | — | |

| 2012 | The Longest Daycare | — | Short film Writer and producer |

| 2013 | I Know That Voice | Himself | Documentary |

| 2015 | I Thought I Told You to Shut Up!! | Himself | Short documentary |

| 2020 | Playdate with Destiny | — | Short film Writer and producer |

| 2021 | The Force Awakens from Its Nap | — | Short film Producer |

| The Good, the Bart, and the Loki | — | ||

| The Simpsons | Balenciaga | — | ||

| Plusaversary | — | ||

| 2022 | When Billie Met Lisa | — | |

| Welcome to the Club | — | ||

| The Simpsons Meet the Bocellis in "Feliz Navidad" | — | ||

| 2023 | Rogue Not Quite One | — |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987–1989 | The Tracey Ullman Show | — | 48 episodes; writer and animator |

| 1989–present | The Simpsons | Himself | Creator, writer, executive producer, character designer and creative consultant Also appeared in 3 episodes as himself |

| 1996 | Space Ghost Coast to Coast | Himself | Episode: "Glen Campbell" |

| 1999 | Olive, the Other Reindeer | Arturo (voice) | TV special; executive producer |

| 1999–2003; 2008–2013; 2023–present |

Futurama | Himself | Creator, writer, and executive producer Also appeared in Episode: "Lrrreconcilable Ndndifferences" as himself |

| 2015 | Portlandia | Himself | Episode: "Fashion" |

| 2018–2023 | Disenchantment | — | Creator, writer, and executive producer |

Video games

| Year | Title | Voice |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | The Simpsons Game | Himself |

| 2014 | The Simpsons: Tapped Out |

Music video

| Year | Title | Artist | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | "Do the Bartman" | Nancy Cartwright | Executive producer |

Theme park

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | The Simpsons Ride | Producer |

Awards

Groening has been nominated for 41 Emmy Awards and has won thirteen, eleven for The Simpsons and two for Futurama in the "Outstanding Animated Program (for programming one hour or less)" category.[105] Groening received the 2002 National Cartoonist Society Reuben Award, and had been nominated for the same award in 2000.[106] He received a British Comedy Award for "outstanding contribution to comedy" in 2004.[107] In 2007, he was ranked fourth (and highest American by birth) in a list of the "top 100 living geniuses", published by British newspaper The Daily Telegraph.[108]

He was awarded the Inkpot Award in 1988.[109]

He received the 2,459th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on February 14, 2012.[110]

Bibliography

- Groening, Matt (1977–2012). Life in Hell

- Love Is Hell (1986) ISBN 0-394-74454-3

- Work Is Hell (1986) ISBN 0-394-74864-6

- School Is Hell (1987) ISBN 0-394-75091-8

- Box Full of Hell (1988) ISBN 0-679-72111-8

- Childhood Is Hell (1988) ISBN 0-679-72055-3

- Greetings from Hell (1989) ISBN 0-679-72678-0

- Akbar and Jeff's Guide to Life (1989) ISBN 0-679-72680-2

- The Big Book of Hell (1990) ISBN 0-679-72759-0

- With Love from Hell (1991) ISBN 0-06-096583-5

- How to Go to Hell (1991) ISBN 0-06-096879-6

- The Road to Hell (1992) ISBN 0-06-096950-4

- Binky's Guide to Love (1994) ISBN 0-06-095078-1

- Love Is Hell: Special Ultra Jumbo 10th Anniversary Edition (1994) ISBN 0-679-75665-5

- The Huge Book of Hell (1997) ISBN 0-14-026310-1

- Will and Abe's Guide to the Universe (2007) ISBN 0-06-134037-5

- Chocano, Carina (January 30, 2001). "Matt Groening". Salon.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- Groening, Matt (1994). "Introduction". Love is Hell: Special Ultra Jumbo 10th Anniversary Edition. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-679-75665-5.

- Groening, Matt (1997). Richmond, Ray; Coffman, Antonia (eds.). The Simpsons: A Complete Guide to Our Favorite Family (1st ed.). New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-06-095252-5. LCCN 98141857. OCLC 37796735. OL 433519M.

- Groening, Matt (2001a). "My Rock 'n' Roll Life, Part One: So You Want To Snort Derisively". Simpsons Comics Royale. New York: Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093378-X.

- Groening, Matt (2001b). "47 Secrets About The Simpsons, A Poem of Sorts, and Some Filler". Simpsons Comics Royale. New York: Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093378-X.

- Groening, Matt (2001c). "The Secret Life of Lisa Simpson". Simpsons Comics Royale. New York: Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093378-X.

- Groth, Gary (April 1991). "Matt Groening". The Comics Journal (141): 78–95.

- Lloyd, Robert (March 24, 1999). "Life in the 31st century". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2005.

- Morgenstern, Joe (April 29, 1990). "Bart Simpson's Real Father". Los Angeles Times Magazine. pp. 12–18, 20, 22.

- Ortved, John (August 2007). "Simpson Family Values". Vanity Fair. No. 564. pp. 70–77. Archived from the original on September 13, 2007. Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- Paul, Alan (September 30, 1995). "Life in Hell". Flux Magazine. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved December 26, 2005.

- Scott, A.O. (November 4, 2001). "Homer's Odyssey". The New York Times Magazine. pp. 42–47. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Turner, Chris (2004). Planet Simpson: How a Cartoon Masterpiece Documented an Era and Defined a Generation. Foreword by Douglas Coupland. (1st ed.). Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0-679-31318-2. OCLC 55682258.

- Von Busack, Richard (November 2, 2001). "'Life' Before Homer". Metroactive. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

References

- ^ a b Joe Otterson (February 9, 2022). "'Futurama' Revival Ordered at Hulu With Original Cast Returning". Variety. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Matt Groening". A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ "Matt Groening Biography". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ Baker, Jeff (March 9, 2004). "Groening, rhymes with reigning". The Oregonian. p. D1.

- ^ "Margaret Ruth Groening Obituary". The Oregonian. May 6, 2013. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013.

- ^ "Homer Groening, Cartoonist's Father, 'Simpsons' Inspiration". The Seattle Times. March 19, 1996. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Rose, Joseph (August 3, 2007). "The real people behind Homer Simpson and family". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "Matt Groening Q&A (1993)". Prodigy. June 1993. Archived from the original on May 10, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- ^ Dueck, Dora (October 7, 2002). "Homer Simpson has Canadian Mennonite roots". Canadian Mennonite. 6 (19). Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ Suderman, Dale (August 15, 2007). "Hillsboro, Home of the Simpsons". Hillsboro Free Press. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ^ a b "Matt Groening Creator and Executive Producer [Bio]". thesimpsons.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- ^ Middlehurst, Charlotte (March 12, 2012). "Matt Groening interview". Time Out Shanghai. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ Rose, Joseph (May 4, 2012). "'The Simpsons' map of Portland (What other proof do you need that they're Oregonians?)". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

Lincoln High School, Southwest 18th Avenue just south of Salmon Street. Groening drew and signed a sidewalk portrait of Bart Simpson in wet concrete outside his alma mater. "Class of 1972" appears next to Bart as he strikes his classic "Don't have a cow, man!" pose.

- ^ a b c d e f Groth (1991).

- ^ "Matt Groening at Evergreen". evergreen.edu. Evergreen State College. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c Lloyd (1999).

- ^ Groening, Matt (w, a). Life in Hell. January 14, 2000, Acme Features Syndicate/5–6.

- ^ a b c Doherty, Brian (March–April 1999). "Matt Groening". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- ^ Groening, Matt; Mirkin, David; Scully, Mike; Anderson, Bob (2005). Commentary for the episode "Two Dozen & One Greyhounds". The Simpsons The Complete Sixth Season (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ "Matt Groening". lambiek.net. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ "Matt Groening says Monty Python influenced new show Disenchantment". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ Groening, Matt (2005). "Foreword". The Complete Peanuts Volume 3 (1955–56). Fantagraphics Books.

- ^ "Matt Groening | Biography, Cartoons, & Facts". Britannica.com. May 18, 2023. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Sheff, David (June 2007). "Matt Groening". Playboy. 54 (6). Archived from the original on October 13, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Morgenstern (1990).

- ^ a b c Von Busack (2001).

- ^ Chocano (2001).

- ^ a b c Rabin, Nathan (April 26, 2006). "Matt Groening". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ^ a b McKenna, Kristine (May–June 2001). "Matt Groening". My Generation. Archived from the original on April 30, 2001. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ "World Wide WET—early". Wunderland.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ "Acme Features Syndicate". Association of Alternative Newsweeklies. Archived from the original on September 2, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- ^ Groening (2001a), pp. 92–93.

- ^ Plume, Kenneth (February 10, 2000). "Interview with Harry Shearer (Part 3 of 4)". IGN. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Ortved (2007), p. 71.

- ^ Groening (1994).

- ^ Bergman, Erik H. (December 16, 1989). "Prime time is heaven for 'Life in Hell' Artist". TV Host. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ Graham, Jefferson (June 19, 2012). "'Life in Hell' is over for cartoonist Matt Groening". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ Sturm, James (October 10, 2012). "To Hell With You, Matt Groening". Slate. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ Kim, John W. (October 1999). "Keep 'em Laughing". Scr(i)pt. Archived from the original on May 26, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d BBC (2000). The Simpsons: America's First Family (6 minute edit for the season 1 DVD) (DVD). UK: 20th Century Fox. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Scott (2001).

- ^ Rose, Charlie (Host, Executive producer) (July 30, 2007). Charlie Rose:A Conversation About The Simpsons Movie (Television production). Charlie Rose, Inc. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ a b Duncan, Andrew (September 18–24, 1999). "Matt Groening". Radio Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2001. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- ^ Turner (2004).

- ^ a b c d Paul (1995).

- ^ "Index to Comic Art Collection: "Gro" to "Groenne"". Michigan State University Libraries. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ Groening, Matt. (2005). Commentary for "Fear of Flying", in The Simpsons: The Complete Sixth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Groening (2001b), p. 90.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (July 22, 2007). "Screen Dreams". The New York Times Magazine. p. 15. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ Silverman, David; Archer, Wes. (2004). Illustrated commentary for "Treehouse of Horror IV", in The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Anderson, Mike B.; Groening, Matt; Michels, Pete; Smith, Yeardley. (2006). "A Bit From the Animators", Illustrated Commentary for "All Singing, All Dancing", in The Simpsons: The Complete Ninth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Groening, Matt; Reiss, Mike; Kirkland, Mark. (2002). Commentary for "Principal Charming", in The Simpsons: The Complete Second Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Silverman, David; Reardon, Jim; Groening, Matt. (2005). Illustrated commentary for "Treehouse of Horror V", in The Simpsons: The Complete Sixth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Groening, Matt. (2006). "A Bit From the Animators", illustrated commentary for "All Singing, All Dancing", in The Simpsons: The Complete Ninth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Heintjes. "The David Silverman Interview". Hogan's Alley. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ^ Groening (1997), p. 14.

- ^ Groening, Matt (2002). The Simpsons season 2 DVD commentary for the episode "Old Money" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b Ortved (2007), p. 72.

- ^ Kuipers, Dean (April 15, 2004). "3rd Degree: Harry Shearer". Los Angeles: City Beat. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved September 1, 2006.

- ^ Tucker, Ken (March 12, 1993). "Toon Terrific". Entertainment Weekly. p. 48(3).

- ^ "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire" Archived July 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine The Simpsons.com. Retrieved on February 5, 2007

- ^ Groening, Matt (2001). The Simpsons season 1 DVD commentary for the episode "Some Enchanted Evening" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Snierson, Dan (July 18, 2007). "Conan on being left out of "Simpsons Movie"". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ Groening (2001b), pp. 90–91.

- ^ Blake, Joseph (January 6, 2007). "Painting the town in Portland". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ^ Larry Carroll (July 26, 2007). "'Simpsons' Trivia, From Swearing Lisa To 'Burns-Sexual' Smithers". MTV. Archived from the original on December 20, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ From a radio interview with Groening that aired on the April 22, 1998 edition Archived October 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine of Fresh Air on NPR. Link to stream (13 minutes, 21 seconds in)

- ^ Groening, Matt; Oakley, Bill;, Weinstein, Josh; Appel, Richard; Cohen, David; Pulido, Rachel; Smith, Yeardley; Reardon, Jim; Silverman, David (2005). The Simpsons The Complete Seventh Season DVD commentary for the episode "22 Short Films About Springfield" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Brennan, Judy (March 3, 1995). "Matt Groening's Reaction to The Critic's First Appearance on The Simpsons". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 31, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (April 2, 2006). "Homer going to bat in '07". Variety. Archived from the original on October 29, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ a b Needham, Alex (October 1999). "Nice Planet...We'll Take It!". The Face (33). Archived from the original on August 24, 2000.

- ^ Katz, Claudia (November 16, 2007). "EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: Claudia Katz on Futurama the Movie: Bender's Big Score" (Interview). Interviewed by Evan Jacobs. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ^ Wortham, Jenna (November 4, 2008). "Futurama Animators Roll 20-Sided Die With Bender's Game". Wired. Archived from the original on May 5, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (February 26, 2009). "Matt Groening looks to the future". CNN. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Ausiello, Michael (June 9, 2009). "It's official: 'Futurama' is reborn!". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ^ Hibberd, James (March 24, 2011). "'Futurama' renewed for two more years!". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 28, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ Marechal, AJ (April 22, 2013). "Toon comedy has logged seasons on Fox, Comedy Central since 1999". Variety. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ "'Simpsons' Creator Matt Groening in Talks with Netflix for Animated Series". January 15, 2016. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "Matt Groening Netflix Animated Comedy A Go With 20-Episode Order, Abbi Jacobson, Nat Faxon & Eric Andre Lead Voice Cast". Deadline. July 25, 2017. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (July 29, 2018). "Matt Groening Talks Origins of New Netflix Series 'Disenchantment'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (July 25, 2017). "Matt Groening Netflix Animated Comedy A Go With 20-Episode Order, Abbi Jacobson, Nat Faxon & Eric Andre Lead Voice Cast". Deadline. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ Groening (2001c), p. 128.

- ^ "Comic Book Covers". Mary Fleener. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- ^ Zograf, Aleksandar. "Meet The End of The Century With... Gary Panter". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ a b Payne, John (November 5, 2003). "All Tomorrow's Parties Today". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on September 26, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ Dacapo Books Archived February 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on September 4, 2007.

- ^ All Tomorrow's Parties – Archive Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on September 4, 2007.

- ^ "Frank Zappa Plays The Music Of Frank Zappa". globalia.net. Archived from the original on April 11, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Rock Bottom Remainders Official site Archived December 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on March 4, 2007

- ^ "Hard Listening". The Rock Bottom Remainders. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ ""Simpsons" Creator Scoops Up Santa Monica Crib". Open House. NBC. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ^ "Photos of Simpsons creator and his son Nathaniel". Perfil.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Madre e hija embarazadas: la esposa argentina de Matt Groening y su hija, en la dulce espera Archived August 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, December 16, 2015

- ^ [1] Instagram June 19, 2018.

- ^ "aguspicassogroening on Instagram: "nirvana"". Instagram. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ "aguspicassogroening on Instagram: "One month of my zen baby Satori … his name is Him… thanks @chriscallahanphotography"". Instagram. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ "'The Simpsons' Creator's Sister, Lisa, Splits from 'Hey Arnold' Creator After 30 Years of Marriage". August 8, 2018. Archived from the original on November 30, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ^ Craig Bartlett's Charmed Past Life Archived June 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Awn.com. December 1998. Retrieved on December 29, 2011.

- ^ "QUESTIONS FOR: Matt Groening". The New York Times. December 27, 1998. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

I'm an agnostic

- ^ Allen, Norm. "Yes, There Is A Hell". Free Inquiry. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved February 26, 2007.

- ^ "Matt Groening's Federal Campaign Contribution Report". Newsmeat.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2007.

- ^ Mortenson, Eric (November 19, 2004). "Lawmaker feels void after mother's death". The Oregonian.

- ^ Wired. February 1999. p. 158.

- ^ "Remember When Richard Nixon Was the Most Corrupt President Futurama Could Imagine?". Paste Magazine. Archived from the original on January 5, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ "Advanced Primetime Awards Search". emmys.org. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- ^ "Cartoonist of the Year". reuben.org. National Cartoonists Society. Archived from the original on August 28, 2001. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "The Past Winners". British Comedy Awards. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ "Top 100 living geniuses". October 30, 2007. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Inkpot Award". December 6, 2012. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Riedel, David (June 24, 2011). "Jennifer Aniston, Vin Diesel among Hollywood Walk of Fame class of 2012". CBS News. Archived from the original on June 26, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

External links

- 1954 births

- 20th-century American male artists

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- 21st-century American male artists

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American screenwriters

- American album-cover and concert-poster artists

- Alternative cartoonists

- American anti-fascists

- American agnostics

- American animated film producers

- American cartoonists

- American comics artists

- American comics writers

- American comedy writers

- American comic strip cartoonists

- American illustrators

- American male screenwriters

- American male television writers

- American Mennonites

- American parodists

- American people of Canadian descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Norwegian descent

- American satirists

- American showrunners

- American surrealist artists

- American television producers

- American television writers

- Animators from Oregon

- Annie Award winners

- Artists from Portland, Oregon

- Comedians from Oregon

- Evergreen State College alumni

- Film producers from Oregon

- Inkpot Award winners

- Lincoln High School (Portland, Oregon) alumni

- Living people

- Mennonite writers

- Mennonite artists

- Mennonite humorists

- Oregon Democrats

- Peabody Award winners

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Reuben Award winners

- Rock Bottom Remainders members

- Screenwriters from Oregon

- Showrunners of animated series

- Television producers from Oregon

- Writers from Portland, Oregon