Negative responsiveness: Difference between revisions

Expanding article |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Altered template type. Add: isbn, jstor, authors 1-1. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Closed Limelike Curves | Category:Electoral system criteria | #UCB_Category 23/33 |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{about|the voting system criterion|the mathematical notion of a function that doesn't "bend"|monotonic function|the concept of population or voter monotonicity|Participation criterion}} {{Electoral systems sidebar|expanded=Paradox}} |

{{about|the voting system criterion|the mathematical notion of a function that doesn't "bend"|monotonic function|the concept of population or voter monotonicity|Participation criterion}} {{Electoral systems sidebar|expanded=Paradox}} |

||

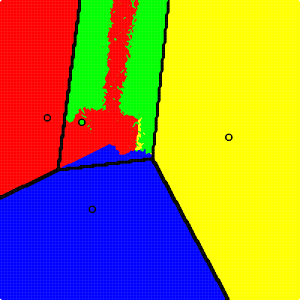

[[File:IRV_Yee.svg|alt=A diagram showing who would win an IRV election for different electorates. The win region for each candidate is erratic, with random pixels dotting the image and jagged, star-shaped (convex) regions occupying much of the image. Moving the electorate to the left can cause a right-wing candidate to win, and vice versa.|thumb|300x300px|A 4-candidate [https://electowiki.org/wiki/Yee_diagram Yee diagram] under IRV. The diagram shows who would win an IRV election if the electorate is centered at a particular point. Moving the electorate to the left can cause a right-wing candidate to win, and vice versa. Black lines show the [[Voronoi diagram|optimal solution]] (achieved by [[Condorcet method|Condorcet]] or [[Score voting|score]] voting).]] |

[[File:IRV_Yee.svg|alt=A diagram showing who would win an IRV election for different electorates. The win region for each candidate is erratic, with random pixels dotting the image and jagged, star-shaped (convex) regions occupying much of the image. Moving the electorate to the left can cause a right-wing candidate to win, and vice versa.|thumb|300x300px|A 4-candidate [https://electowiki.org/wiki/Yee_diagram Yee diagram] under IRV. The diagram shows who would win an IRV election if the electorate is centered at a particular point. Moving the electorate to the left can cause a right-wing candidate to win, and vice versa. Black lines show the [[Voronoi diagram|optimal solution]] (achieved by [[Condorcet method|Condorcet]] or [[Score voting|score]] voting).]] |

||

In [[Social choice theory|social choice]], '''negative'''<ref>{{Cite journal |last=May |first=Kenneth O. |date=1952 |title=A Set of Independent Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Simple Majority Decision |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1907651 |journal=Econometrica |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=680–684 |doi=10.2307/1907651 |issn=0012-9682 |jstor=1907651}}</ref>'''<ref name=":422">{{Cite book |last=Pukelsheim |first=Friedrich |url=http://archive.org/details/proportionalrepr0000puke |title=Proportional representation : apportionment methods and their applications |date=2014 |publisher=Cham; New York : Springer |others=Internet Archive |isbn=978-3-319-03855-1}}</ref>''' or '''perverse response'''<ref>{{Cite journal | |

In [[Social choice theory|social choice]], '''negative'''<ref>{{Cite journal |last=May |first=Kenneth O. |date=1952 |title=A Set of Independent Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Simple Majority Decision |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1907651 |journal=Econometrica |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=680–684 |doi=10.2307/1907651 |issn=0012-9682 |jstor=1907651}}</ref>'''<ref name=":422">{{Cite book |last=Pukelsheim |first=Friedrich |url=http://archive.org/details/proportionalrepr0000puke |title=Proportional representation : apportionment methods and their applications |date=2014 |publisher=Cham; New York : Springer |others=Internet Archive |isbn=978-3-319-03855-1}}</ref>''' or '''perverse response'''<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Doron |first1=Gideon |last2=Kronick |first2=Richard |date=1977 |title=Single Transferrable Vote: An Example of a Perverse Social Choice Function |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2110496 |journal=American Journal of Political Science |volume=21 |issue=2 |pages=303–311 |doi=10.2307/2110496 |jstor=2110496 |issn=0092-5853}}</ref> is a [[Pathological (mathematics)#In voting and social choice|pathological behavior]] of some [[Electoral system|voting rules]], where increasing an option's [[Ranked voting|ranking]] or [[Rated voting|rating]] causes them to lose.<ref name="Woodall-Monotonicity22">D R Woodall, [http://www.votingmatters.org.uk/ISSUE6/P4.HTM "Monotonicity and Single-Seat Election Rules"], ''[[Voting matters]]'', Issue 6, 1996</ref> Electoral systems that do not exhibit perversity are said to satisfy the '''positive response''' or [[Monotonic function|'''monotonicity''']] '''criterion'''. |

||

Perversity is often described by social choice theorists as an exceptionally severe kind of [[Pathological (mathematics)#In voting and social choice|electoral pathology]].<ref>{{Cite journal | |

Perversity is often described by social choice theorists as an exceptionally severe kind of [[Pathological (mathematics)#In voting and social choice|electoral pathology]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Felsenthal |first1=Dan S. |last2=Tideman |first2=Nicolaus |date=2014-01-01 |title=Interacting double monotonicity failure with direction of impact under five voting methods |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165489613000723 |journal=Mathematical Social Sciences |volume=67 |pages=57–66 |doi=10.1016/j.mathsocsci.2013.08.001 |issn=0165-4896}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Arrow |first=Kenneth J. |date=2017-12-13 |title=Social Choice and Individual Values |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.12987/9780300186987 |doi=10.12987/9780300186987 |isbn=978-0-300-18698-7 |quote=Since we are trying to describe social welfare and not some sort of illfare, we must assume that the social welfare function is such that the social ordering responds positively to alterations in individual values, or at least not negatively. Hence, if one alternative social state rises or remains still in the ordering of every individual without any other change in those orderings, we expect that it rises, or at least does not fall, in the social ordering.}}</ref> Systems that allow for perverse response can create situations where a voter's ballot has a reversed effect on the election, thus treating the [[Social welfare function|well-being of some voters]] as "less than worthless".<ref name=":1" /> Similar arguments have led to constitutional prohibitions on such systems as violating the right to [[One man, one vote|equal and direct suffrage]].<ref name=":4232">{{Cite book |last=Pukelsheim |first=Friedrich |url=http://archive.org/details/proportionalrepr0000puke |title=Proportional representation : apportionment methods and their applications |date=2014 |publisher=Cham; New York : Springer |others=Internet Archive |isbn=978-3-319-03855-1}}</ref><ref name=":032">{{Cite news |last=dpa |date=2013-02-22 |title=Bundestag beschließt neues Wahlrecht |url=https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2013-02/bundestag-wahlrecht-beschluss |access-date=2024-05-02 |work=Die Zeit |language=de-DE |issn=0044-2070}}</ref> Negative response is often cited as an example of a [[perverse incentive]], as voting rules with perverse response incentivize politicians to take unpopular or [[Center squeeze|extreme]] positions in an attempt to shed excess votes. |

||

Most [[Ranked voting|ranked methods]] (including [[Borda count|Borda]] and all common [[Round-robin voting|round-robin rules]]) satisfy positive response,<ref name="Woodall-Monotonicity22" /> as do all common [[rated voting]] methods (including [[Approval voting|approval]], [[Highest median voting rules|highest medians]], and [[Score voting|score]]).{{NoteTag|Apart from majority judgment, these systems satisfy an even stronger form of positive responsiveness: if there is a tie, any increase in a candidate's rating will break the tie in that candidate's favor.}} The [[Maximal lotteries|randomized Condorcet method]] may occasionally violate monotonicity in the case of [[Condorcet cycle|cyclic ties]]. |

Most [[Ranked voting|ranked methods]] (including [[Borda count|Borda]] and all common [[Round-robin voting|round-robin rules]]) satisfy positive response,<ref name="Woodall-Monotonicity22" /> as do all common [[rated voting]] methods (including [[Approval voting|approval]], [[Highest median voting rules|highest medians]], and [[Score voting|score]]).{{NoteTag|Apart from majority judgment, these systems satisfy an even stronger form of positive responsiveness: if there is a tie, any increase in a candidate's rating will break the tie in that candidate's favor.}} The [[Maximal lotteries|randomized Condorcet method]] may occasionally violate monotonicity in the case of [[Condorcet cycle|cyclic ties]]. |

||

However, the criterion is violated most often by [[instant-runoff voting]],<ref name=":322">{{Cite journal |last1=Ornstein |first1=Joseph T. |last2=Norman |first2=Robert Z. |date=2014-10-01 |title=Frequency of monotonicity failure under Instant Runoff Voting: estimates based on a spatial model of elections |journal=Public Choice |language=en |volume=161 |issue=1–2 |pages=1–9 |doi=10.1007/s11127-013-0118-2 |issn=0048-5829 |s2cid=30833409}}</ref> the [[single transferable vote]],<ref>{{Cite journal | |

However, the criterion is violated most often by [[instant-runoff voting]],<ref name=":322">{{Cite journal |last1=Ornstein |first1=Joseph T. |last2=Norman |first2=Robert Z. |date=2014-10-01 |title=Frequency of monotonicity failure under Instant Runoff Voting: estimates based on a spatial model of elections |journal=Public Choice |language=en |volume=161 |issue=1–2 |pages=1–9 |doi=10.1007/s11127-013-0118-2 |issn=0048-5829 |s2cid=30833409}}</ref> the [[single transferable vote]],<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Doron |first1=Gideon |last2=Kronick |first2=Richard |date=1977 |title=Single Transferrable Vote: An Example of a Perverse Social Choice Function |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2110496 |journal=American Journal of Political Science |volume=21 |issue=2 |pages=303–311 |doi=10.2307/2110496 |jstor=2110496 |issn=0092-5853}}</ref> and [[Hamilton's method|Hamilton's apportionment method]].<ref name=":422" /> The paradox is especially common in [[Ranked-choice voting|ranked-choice voting (RCV-IRV)]] and the [[two-round system]],<ref name=":33">{{Cite journal |last1=Ornstein |first1=Joseph T. |last2=Norman |first2=Robert Z. |date=2014-10-01 |title=Frequency of monotonicity failure under Instant Runoff Voting: estimates based on a spatial model of elections |journal=Public Choice |language=en |volume=161 |issue=1–2 |pages=1–9 |doi=10.1007/s11127-013-0118-2 |issn=0048-5829 |s2cid=30833409}}</ref> a behavior which can lead to [[Center squeeze|the elimination of moderate candidates]] and tends to favor extremists.<ref name=":8322">{{Cite journal |last1=McGann |first1=Anthony J. |last2=Koetzle |first2=William |last3=Grofman |first3=Bernard |date=2002 |title=How an Ideologically Concentrated Minority Can Trump a Dispersed Majority: Nonmedian Voter Results for Plurality, Run-off, and Sequential Elimination Elections |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3088418 |journal=American Journal of Political Science |volume=46 |issue=1 |pages=134–147 |doi=10.2307/3088418 |issn=0092-5853 |jstor=3088418 |quote=}}</ref> |

||

The [[participation criterion]] is a closely-related, but different, concept. While positive responsiveness deals with a voter changing their opinion (or vote), participation deals with situations where a voter choosing to ''cast'' a ballot has a reversed effect on the election. |

The [[participation criterion]] is a closely-related, but different, concept. While positive responsiveness deals with a voter changing their opinion (or vote), participation deals with situations where a voter choosing to ''cast'' a ballot has a reversed effect on the election. |

||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

=== Real-world situations === |

=== Real-world situations === |

||

==== Alaska 2022 ==== |

==== Alaska 2022 ==== |

||

[[2022 Alaska's at-large congressional district special election|Alaska's first-ever instant-runoff election]] resulted in negative vote weights for many [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] supporters of [[Sarah Palin]], who could have defeated [[Mary Peltola]] by placing her first on their ballots.<ref>{{Cite journal | |

[[2022 Alaska's at-large congressional district special election|Alaska's first-ever instant-runoff election]] resulted in negative vote weights for many [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] supporters of [[Sarah Palin]], who could have defeated [[Mary Peltola]] by placing her first on their ballots.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Graham-Squire |first1=Adam |last2=McCune |first2=David |date=2024-01-02 |title=Ranked Choice Wackiness in Alaska |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10724117.2023.2224675 |journal=Math Horizons |language=en |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=24–27 |doi=10.1080/10724117.2023.2224675 |issn=1072-4117}}</ref> |

||

==== Burlington, Vermont ==== |

==== Burlington, Vermont ==== |

||

Revision as of 17:36, 30 September 2024

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

In social choice, negative[1][2] or perverse response[3] is a pathological behavior of some voting rules, where increasing an option's ranking or rating causes them to lose.[4] Electoral systems that do not exhibit perversity are said to satisfy the positive response or monotonicity criterion.

Perversity is often described by social choice theorists as an exceptionally severe kind of electoral pathology.[5][6] Systems that allow for perverse response can create situations where a voter's ballot has a reversed effect on the election, thus treating the well-being of some voters as "less than worthless".[6] Similar arguments have led to constitutional prohibitions on such systems as violating the right to equal and direct suffrage.[7][8] Negative response is often cited as an example of a perverse incentive, as voting rules with perverse response incentivize politicians to take unpopular or extreme positions in an attempt to shed excess votes.

Most ranked methods (including Borda and all common round-robin rules) satisfy positive response,[4] as do all common rated voting methods (including approval, highest medians, and score).[note 1] The randomized Condorcet method may occasionally violate monotonicity in the case of cyclic ties.

However, the criterion is violated most often by instant-runoff voting,[9] the single transferable vote,[10] and Hamilton's apportionment method.[2] The paradox is especially common in ranked-choice voting (RCV-IRV) and the two-round system,[11] a behavior which can lead to the elimination of moderate candidates and tends to favor extremists.[12]

The participation criterion is a closely-related, but different, concept. While positive responsiveness deals with a voter changing their opinion (or vote), participation deals with situations where a voter choosing to cast a ballot has a reversed effect on the election.

By method

Runoff-based voting systems such as ranked choice voting (RCV) are typically vulnerable to perverse response. A notable example is the 2009 Burlington mayoral election, the United States' second instant-runoff election in the modern era, where Bob Kiss won the election as a result of 750 ballots ranking him in last place.[13]

An example with three parties (Top, Center, Bottom) is shown below. In this scenario, the Bottom party initially loses. However, they are elected after running an unsuccessful campaign and adopting an unpopular platform, which pushes their supporters away from the party and into the Top party.

| Popular Bottom | Unpopular Bottom | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 1 | Round 2 | |||

| Top | +6% | Top | 31% | 46% | ||

| Center | 30% | 55% |

↗ | Center | ||

| Bottom | 45% | 45% | -6% | Bottom | 39% | 54% |

This election is an example of a center-squeeze, a class of elections where instant-runoff and plurality have difficulties electing the majority-preferred candidate, because the first-round vote is split between an extremist and a moderate. Here, the loss of support for Bottom policies makes the Top party more popular, allowing it to defeat the Center party in the first round.

A famous example of a less-is-more paradox can be seen in the 2022 Alaska at-large special election.

Quota rules

Proportional representation systems using largest remainders for apportionment do not pass the positive response criterion. This happened in the 2005 German federal election, when CDU voters in Dresden were instructed to vote for the FDP, a strategy that allowed the party an additional seat.[2] As a result, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that negative voting weights violate the German constitution's guarantee of equal and direct suffrage.[14]

Frequency of violations

For electoral methods failing positive value, the frequency of less-is-more paradoxes will depend on the electoral method, the candidates, and the distribution of outcomes. Negative voting weights tend to be most common with instant-runoff, with what some researchers have described as an "unacceptably high" frequency.[11]

Theoretical models

Results using the impartial culture model estimate about 15% of elections with 3 candidates;[15][16] however, the true probability may be much higher, especially when restricting observation to close elections.[17] For moderate numbers of candidates, the probability of a less-is-more paradoxes quickly approaches 100%.[citation needed]

A 2013 study using a two-dimensional spatial model of voting estimated at least 15% of IRV elections would be nonmonotonic in the best-case scenario (with only three equally-competitive candidates). The researchers concluded that "three-way competitive races will exhibit unacceptably frequent monotonicity failures" and "In light of these results, those seeking to implement a fairer multi-candidate election system should be wary of adopting IRV."[11]

Real-world situations

Alaska 2022

Alaska's first-ever instant-runoff election resulted in negative vote weights for many Republican supporters of Sarah Palin, who could have defeated Mary Peltola by placing her first on their ballots.[18]

Burlington, Vermont

In Burlington's second IRV election, incumbent Bob Kiss was re-elected, despite losing in a head-to-head matchup with Democrat Andy Montroll (the Condorcet winner). However, if Kiss had gained more support from Wright voters, Kiss would have lost.[13]

Survey of nonmonotonic elections

A survey of 185 American instant-runoff elections where no candidate was ranked first by a majority of voters found five additional elections containing monotonicity failures.[13]

2005 German Election in Dresden

A negative voting weight event famously resulted in the abolition of Hamilton's method for apportionment in Germany after the 2005 federal election. CDU voters in Dresden were instructed to strategically vote for the FDP, a strategy that allowed the party to earn an additional seat, causing substantial controversy. As a result, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that negative voting weights violate the German constitution's guarantee of equal and direct suffrage.[2]

See also

- Participation criterion, a closely-related concept

- Voting system

- Voting system criterion

- Monotone preferences in consumer theory

- Monotonicity (mechanism design)

- Maskin monotonicity

Notes

- ^ Apart from majority judgment, these systems satisfy an even stronger form of positive responsiveness: if there is a tie, any increase in a candidate's rating will break the tie in that candidate's favor.

References

- ^ May, Kenneth O. (1952). "A Set of Independent Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Simple Majority Decision". Econometrica. 20 (4): 680–684. doi:10.2307/1907651. ISSN 0012-9682. JSTOR 1907651.

- ^ a b c d Pukelsheim, Friedrich (2014). Proportional representation : apportionment methods and their applications. Internet Archive. Cham; New York : Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-03855-1.

- ^ Doron, Gideon; Kronick, Richard (1977). "Single Transferrable Vote: An Example of a Perverse Social Choice Function". American Journal of Political Science. 21 (2): 303–311. doi:10.2307/2110496. ISSN 0092-5853. JSTOR 2110496.

- ^ a b D R Woodall, "Monotonicity and Single-Seat Election Rules", Voting matters, Issue 6, 1996

- ^ Felsenthal, Dan S.; Tideman, Nicolaus (2014-01-01). "Interacting double monotonicity failure with direction of impact under five voting methods". Mathematical Social Sciences. 67: 57–66. doi:10.1016/j.mathsocsci.2013.08.001. ISSN 0165-4896.

- ^ a b Arrow, Kenneth J. (2017-12-13). Social Choice and Individual Values. doi:10.12987/9780300186987. ISBN 978-0-300-18698-7.

Since we are trying to describe social welfare and not some sort of illfare, we must assume that the social welfare function is such that the social ordering responds positively to alterations in individual values, or at least not negatively. Hence, if one alternative social state rises or remains still in the ordering of every individual without any other change in those orderings, we expect that it rises, or at least does not fall, in the social ordering.

- ^ Pukelsheim, Friedrich (2014). Proportional representation : apportionment methods and their applications. Internet Archive. Cham; New York : Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-03855-1.

- ^ dpa (2013-02-22). "Bundestag beschließt neues Wahlrecht". Die Zeit (in German). ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Ornstein, Joseph T.; Norman, Robert Z. (2014-10-01). "Frequency of monotonicity failure under Instant Runoff Voting: estimates based on a spatial model of elections". Public Choice. 161 (1–2): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s11127-013-0118-2. ISSN 0048-5829. S2CID 30833409.

- ^ Doron, Gideon; Kronick, Richard (1977). "Single Transferrable Vote: An Example of a Perverse Social Choice Function". American Journal of Political Science. 21 (2): 303–311. doi:10.2307/2110496. ISSN 0092-5853. JSTOR 2110496.

- ^ a b c Ornstein, Joseph T.; Norman, Robert Z. (2014-10-01). "Frequency of monotonicity failure under Instant Runoff Voting: estimates based on a spatial model of elections". Public Choice. 161 (1–2): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s11127-013-0118-2. ISSN 0048-5829. S2CID 30833409.

- ^ McGann, Anthony J.; Koetzle, William; Grofman, Bernard (2002). "How an Ideologically Concentrated Minority Can Trump a Dispersed Majority: Nonmedian Voter Results for Plurality, Run-off, and Sequential Elimination Elections". American Journal of Political Science. 46 (1): 134–147. doi:10.2307/3088418. ISSN 0092-5853. JSTOR 3088418.

- ^ a b c Graham-Squire, Adam T.; McCune, David (2023-06-12). "An Examination of Ranked-Choice Voting in the United States, 2004–2022". Representation: 1–19. arXiv:2301.12075. doi:10.1080/00344893.2023.2221689.

- ^ dpa (2013-02-22). "Bundestag beschließt neues Wahlrecht". Die Zeit (in German). ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Miller, Nicholas R. (2016). "Monotonicity Failure in IRV Elections with Three Candidates: Closeness Matters" (PDF). University of Maryland Baltimore County (2nd ed.). Table 2. Retrieved 2020-07-26.

Impartial Culture Profiles: All, TMF: 15.1%

- ^ Miller, Nicholas R. (2012). MONOTONICITY FAILURE IN IRV ELECTIONS WITH THREE ANDIDATES (PowerPoint). p. 23.

Impartial Culture Profiles: All, Total MF: 15.0%

- ^ Quas, Anthony (2004-03-01). "Anomalous Outcomes in Preferential Voting". Stochastics and Dynamics. 04 (1): 95–105. doi:10.1142/S0219493704000912. ISSN 0219-4937.

- ^ Graham-Squire, Adam; McCune, David (2024-01-02). "Ranked Choice Wackiness in Alaska". Math Horizons. 31 (1): 24–27. doi:10.1080/10724117.2023.2224675. ISSN 1072-4117.