Cyrus Edwin Dallin: Difference between revisions

AndrewTJay (talk | contribs) m Added two sculptures of indiegenous chiefs along with a reference for them. |

AndrewTJay (talk | contribs) added in wealthy backers by name |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

Dallin was born in [[Springville, Utah|Springville]], [[Utah Territory]], the son of Thomas and Jane (Hamer) Dallin, both of whom had left [[the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]] before their marriage. |

Dallin was born in [[Springville, Utah|Springville]], [[Utah Territory]], the son of Thomas and Jane (Hamer) Dallin, both of whom had left [[the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]] before their marriage. |

||

At age 19, Dallin moved from Utah to [[Boston]] to study sculpture with [[Truman Howe Bartlett]]. He then studied in with [[Henri Chapu]] and at the [[Académie Julian]] in [[Paris]].<ref name="harvardsquarelibrary.org">{{cite web |title=Cyrus Dallin: American Sculptor |website=Notable Unitarian |publisher=Harvard Square Library |date=November 14, 1944 |url=http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/unitarians/dallin.html |access-date=February 12, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120304111929/http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/unitarians/dallin.html |archive-date=March 4, 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

At age 19, Dallin moved from Utah to [[Boston]] to study sculpture with [[Truman Howe Bartlett]]. Two wealthy Utah mining investors; C.H. Blanchard and Jacob Lawrence funded his move.<ref name=":0" /> He then studied in with [[Henri Chapu]] and at the [[Académie Julian]] in [[Paris]].<ref name="harvardsquarelibrary.org">{{cite web |title=Cyrus Dallin: American Sculptor |website=Notable Unitarian |publisher=Harvard Square Library |date=November 14, 1944 |url=http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/unitarians/dallin.html |access-date=February 12, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120304111929/http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/unitarians/dallin.html |archive-date=March 4, 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

==Career== |

==Career== |

||

Revision as of 19:30, 1 October 2024

Cyrus Edwin Dallin | |

|---|---|

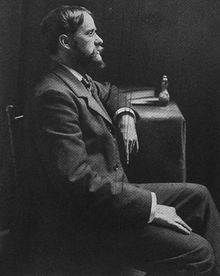

Dallin in c. 1880 | |

| Born | November 22, 1861 Springville, Utah, U.S. |

| Died | November 14, 1944 (aged 82) Arlington, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Académie Julian |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | The Angel Moroni (1893) Appeal to the Great Spirit (1908) Paul Revere (1940) |

| Spouse | Vittoria Colonna Murray |

Cyrus Edwin Dallin (November 22, 1861 – November 14, 1944) was an American sculptor best known for his depictions of Native Americans. He created more than 260 works, including the Equestrian Statue of Paul Revere in Boston; the Angel Moroni atop Salt Lake Temple in Salt Lake City; and Appeal to the Great Spirit (1908), at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He was also an accomplished painter and an Olympic archer.[1]

Early life and education

Dallin was born in Springville, Utah Territory, the son of Thomas and Jane (Hamer) Dallin, both of whom had left the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints before their marriage.

At age 19, Dallin moved from Utah to Boston to study sculpture with Truman Howe Bartlett. Two wealthy Utah mining investors; C.H. Blanchard and Jacob Lawrence funded his move.[2] He then studied in with Henri Chapu and at the Académie Julian in Paris.[3]

Career

In 1883, Dallin entered a competition to sculpt an equestrian statue of Paul Revere for Boston, Massachusetts. He won the competition and received a contract, but six versions of his model were rejected. The fifth model was not accepted because of fundraising problems. The seventh version was accepted in 1939 and the full-size statue was unveiled in 1940.[4][5]

Dallin converted to Unitarianism and initially turned down the offer to sculpt the angel Moroni for the spire of the LDS Church's Salt Lake Temple. He later accepted the commission and, after finishing the statue said, "My angel Moroni brought me nearer to God than anything I ever did."[6][7] His statue became a symbol for the LDS Church and was the model for other angel Moroni statues on the spires of LDS Church temples.[8]

In Boston, Dallin became a colleague of Augustus St. Gaudens and a close friend of John Singer Sargent. He married Vittoria Colonna Murray in 1891 and returned to Utah to work on The Angel Moroni (1893). He taught for a year at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, while completing his Sir Isaac Newton (1895) for the Library of Congress. In 1897, he traveled to Paris, and studied with Jean Dampt. In 1889 and 1890 he developed a friendship with prominent European painter Rosa Bonheur. Together they traveled to Neuilly outside of Paris to sketch the animals and cast of Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show at their encampment.[9]

He entered a Don Quixote statuette in the Salon of 1897, and The Medicine Man in the Salon of 1899 and the Exposition Universelle (1900).[3] The couple moved to Arlington, Massachusetts, in 1900, where they established their residence and raised three sons.

| Medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men's Archery | ||

| Representing the | ||

| Olympic Games | ||

| 1904 St. Louis | Team round | |

At the 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis, Dallin competed in archery, winning the bronze medal in the team competition.[10] He finished ninth in the Double American round and 12th in the Double York round.[11]

From 1899 to 1941, he was a member of the faculty of Massachusetts Normal Art School, now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, where his more notable students included Bashka Paeff, Vincent Schofield Wickham and Ruth Johnston Surez.[12] In 1912, he was elected to the National Academy of Design as an Associate member and became a full Academician in 1930. He also was a member of the National Sculpture Society and the National Association of Arts and Letters, as well as an associate at the National Academy of Design.[13]

Equestrian sculptures of indigenous peoples

Dallin created four prominent equestrian sculptures of indigenous people: A Signal of Peace, or The Welcome (1890); The Medicine Man, or The Warning (1899); Protest of the Sioux, or The Defiance (1904); and Appeal to the Great Spirit (1908).[14][15]

A Signal of Peace was exhibited at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and was installed in Chicago's Lincoln Park in 1894. The Medicine Man was exhibited at the 1899 Paris Salon, and the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where it won a gold medal.[16] It was installed in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park in 1903.

The full-size staff version of Protest of the Sioux was exhibited at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, where it won a gold medal. The mounted brave defiantly shaking his fist at an enemy was never cast as a full-size bronze and survives only in statuette form. A one-third-size bronze version, cast in 1986, is at the Springville Museum of Art in Springville, Utah.[17]

Appeal to the Great Spirit became an icon of American art and is Dallin's most famous work.[18] The full-size version was cast in bronze in Paris and won a gold medal at the 1909 Paris Salon. It was installed outside the main entrance to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1912. Smaller versions of the work are in numerous American museums and in the permanent collection of the White House.

In 1929, a full-sized bronze version of Appeal to the Great Spirit—personally overseen and approved by Dallin— was installed in Muncie, Indiana, at the intersection of Walnut and Granville Streets, and is considered by many residents to be a symbol of their city. Benefactors of the city would later add to their Dallin portfolio through the purchase of the Passing of the Buffalo sculpture, which had been commissioned by Geraldine R. Dodge. A one-third-size plaster version of the Appeal was given to Tulsa, Oklahoma's Central High in 1923. It stood in the school's main hall until 1976, when Central closed its doors.[19] In 1985, that plaster was used to cast a one-third-size bronze version, which is now in Woodward Park (Tulsa), at the intersection of 21st and Peoria Streets.[20] There is also a version at St. John University in Wisconsin.

-

Protest of the Sioux (1904) at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair

Death

When he died in 1944, his life was celebrated in a Unitarian service. He is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Arlington, Massachusetts.[21]

Legacy

More than sixty of Dallin's works are collected in the Cyrus E. Dallin Museum in the Jefferson Cutter House in Arlington, Massachusetts. Many other of his sculptures are in the vicinity.[22]

An elementary school in Arlington, Massachusetts is named for him.[23]

The Taylor-Dallin House in Arlington where Dallin and his family lived is a privately owned residence and has not been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

More than 30 of Dallin's works are on display at the Springville Museum of Art in his birthplace of Springville, Utah.[4] The Dallin House at 253 S. 300 East Street in Springville is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Dallin's papers are at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.[24]

The Beach Boys based the logo for their Brother Records label on Dallin's sculpture, Appeal to the Great Spirit. [25] In 2020, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College commissioned Cree artist Kent Monkman to prepare a work and he painted The Great Mystery, which reinterprets the Appeal to the Great Spirit sculpture incorporating a Mark Rothko painting in the background. The work is displayed near a mid-sized version of Dallin's sculpture.[26]

From 2017-2020 a race horse named Cyrus Dallin raced in the United Kingdom.[27]

Selected works

- Model for Equestrian Statue of Lafayette (1889) at Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

- The Angel Moroni (1893), atop Salt Lake Temple in Salt Lake City

- Brigham Young Monument (1893), Main and South Temple Streets in Salt Lake City[28][29]

- Sunol (1893), Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame in Goshen, New York

- Sir Isaac Newton (1895), Main Reading Room, Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

- Don Quixote de La Mancha: The Knight of the Windmill (1898), Springville Museum of Art, Springville, Utah[29][30]

- Equestrian statue of Paul Revere (1899, dedicated 1940), Paul Revere Mall, opposite Old North Church in Boston

- View of Hobble Creek (ca 1900), Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City[31]

- Eli Whitney Tablet (1902), Richmond County Courthouse in Augusta, Georgia[32]

- The Picket (1905), Battle of Hanover in Hanover, Pennsylvania[33]

- Victory (1909), Pioneer Park, Provo, Utah[34]

- General Winfield Scott Hancock (1909–10), Pennsylvania State Memorial at Gettysburg Battlefield in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania[35][36]

- Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (1909–1911) at Clinton Square in Syracuse, New York[37]

- My Boys (Dallin Sculpture) (c. 1910) at Robbins Memorial Library in Arlington, Massachusetts

- Robbins Memorial Flagstaff (1914) at Arlington Center Historic District in Arlington, Massachusetts

- Anne Hutchinson (1915, dedicated 1922), Massachusetts Statehouse in Boston[38]

- Alma Mater (Missouri Sculpture) (1916), Mary Institute of Washington University in Ladue, Missouri

- Chief Justice William Cushing Memorial Tablet (1919) Scituate Historical Society in Scituate, Massachusetts

- Governor William Bradford (1920, dedicated 1976), Pilgrim Hall Museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts[39]

- Pilgrim Tercentenary half dollar (1920)

- Signing the Mayflower Compact (1921) in Provincetown, Massachusetts

- Boy and His Dog (1923) in Lincoln, Massachusetts

- Memory (1924) at Sherborn War Memorial in Sherborn, Massachusetts

- Spirit of Life (1929) at Springville Museum of Art in Springville, Utah

- Pioneer Women of Utah (1931) at Springville Museum of Art in Springville, Utah

- Memorial to The Pioneer Mothers of Springville (1932) at Springville City Park in Springville, Utah[40]

Indigenous American works

- A Signal of Peace (1890) at Lincoln Park in Chicago, Illinois

- The Medicine Man (1899) at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia

- Protest of the Sioux (1904)[41]

- A one-third-size bronze version (cast 1986) is in the Springville Museum of Art in Springville, Utah[42]

- Appeal to the Great Spirit (1908) at Boston Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Smaller bronze versions are in Muncie, Indiana[43] and the Museum of the West in Scottsdale, Arizona

- A one-third-size plaster version and a 1985 bronze version cast from that plaster in Tulsa, Oklahoma

- The Scout (1910, dedicated 1922) at Penn Valley Park, Kansas City, Missouri

- A one-third-size bronze version is in Seville, Spain, a 1992 gift from Kansas City, Missouri, Seville's sister-city[44]

- Chief Joseph (1911) at the New York Historical Society in New York City

- Geronimo (1926)[2]

- Menotomy Indian Hunter (1911) at the Arlington Center Historic District in Arlington, Massachusetts

- Massasoit (1920) at Cole's Hill opposite Plymouth Rock in Plymouth, Massachusetts

- Other casts are at Utah State Capitol in Salt Lake City, Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, Springville Museum of Art in Springville, Utah, Mill Creek Park in Kansas City, Missouri, and Dayton Art Institute in Dayton, Ohio

- On the Warpath #28 (c. 1920) at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City[45] and Brookgreen Garden Museum, Brookgreen, South Carolina

- Passing of the Buffalo, also known as The Last Arrow (1929) in Muncie, Indiana

- Pretty Eagle, a portrait bust (sculpted 1910 and cast in 1927)[2]

- Robbins Memorial Flagstaff, (1914) a Native American woman with an infant, at Town Hall in Arlington, Massachusetts

- Sacagawea (1914) at Western Spirit: Scottsdale's Museum of the West in Scottsdale, Arizona with a plaster version at Cyrus Dallin Art Museum in Arlington, Massachusetts

- Sitting Bull (1926)[2]

Gallery

-

Model for Lafayette (1889) at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

-

Sir Isaac Newton (1895) in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

-

Mary Baker Eddy-This work is in storage.

-

Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (1909–1911) at Clinton Square in Syracuse, New York

-

Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument detail

-

My Boys (c. 1910) at Robbins Memorial Library in Arlington, Massachusetts

-

Chief Joseph (1911) at New York Historical Society in New York City

-

Anne Hutchinson (1915, dedicated 1922) at the Massachusetts State House in Boston

-

Massasoit (1920) opposite Plymouth Rock in Plymouth, Massachusetts

-

Memory (1924) at the Sherborn War Memorial in Sherborn, Massachusetts

-

Memorial to the Pioneer Mothers of Springville (1932) in Springville, Utah

-

Woburn Return of the Troops

See also

References

- ^ "Cyrus Edwin Dallin". Olympedia. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Dearinger, David (2004). Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design: 1826-1925 (1st ed.). Hudson Hills Press. p. 144. ISBN 1-55595-029-9.

- ^ a b "Cyrus Dallin: American Sculptor". Notable Unitarian. Harvard Square Library. November 14, 1944. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ a b "Springville Museum of Art". Sma.nebo.edu. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ Francis, Rell Gardner (1994), "Cyrus Edwin Dallin", Utah History Encyclopedia, University of Utah Press, ISBN 9780874804256, archived from the original on March 21, 2024, retrieved April 13, 2024

- ^ Levi Edgar Young, "The Angel Moroni and Cyrus Dallin", Improvement Era, April 1953, p. 234.

- ^ "Sculptor's Works Top Temple Towers Worldwide". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Broder, Patricia Janis; McCracken, Harold (1974). Bronzes of the American West. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-0133-9. OCLC 640913.

- ^ Francis, Rell (1976). Cyrus E. Dallin Let Justice Be Done. Cyrus Dallin Art Museum. pp. 27, 39–40.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cyrus Dallin Olympic medals and stats Archived August 25, 2007, at the Wayback Machine at www.databaseolympics.com

- ^ "Archery - Cyrus Edwin Dallin (United States) : season totals". The-sports.org. September 21, 1904. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Linda (1988). "Sculptress Extraordinarie". Perspectives. 1 (2): 4–5.

- ^ Catalogue of the Exhibition of American Sculpture by the National Sculpture Society. University of Michigan Library as retrieved from Google Books: National Sculpture Society. 1923. p. 41.

- ^ Edward Livermore Burlingame; Robert Bridges; Harlan Logan, eds. (1915). Scribner's magazine. Vol. 57.

- ^ "Sculpture". Hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Cyrus Dallin - American Sculptor". Bronze-gallery.com. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "The Protest". Smofa.org. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "1Win - Revisão do site de apostas brasileiro". www.publicartboston.com (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Tulsa Central High School Foundation Projects". Tulsacentralalumni.org. February 21, 2003. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Appeal to the Great Spirit, (sculpture)". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "Cyrus Dallin and the Angel Moroni". The Pyramid. January 21, 2016. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020 – via heraldextra.com.

- ^ "The Cyrus E. Dallin Art Museum". dallin.org. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "Dallin Elementary School". Arlington.k12.ma.us. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Summary of the Cyrus Edwin Dallin papers, 1883–1970". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ White, Timothy (March 4, 2000). "The Beach Boys: Sons of the Pioneers". Billboard. Vol. 112, no. 10. Prometheus Global Media.

- ^ Powell, Jamie (March 31, 2023). "Kent Monkman: The Great Mystery". Hood Museum. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Pedigree Query Cyrus Dallin". Pedigree Query. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ The Mormon metropolis: an illustrated guide to Salt Lake City and its environs. Magazine Printing Co. 1899. p. 38.

- ^ a b . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 769.

- ^ "Don Quixote de La Mancha: The Knight of the Windmill". Springville Museum of Art. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Utah Museum of Fine Arts. "View of Hobble Creek". Collections.umfa.utah.edu. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ The Whitney Tablet Archived November 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved from the National Textile Association Website, February 9, 2009

- ^ "Battle of Hanover Marker". Hmdb.org. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Indian War Memorial". Markers and Monuments Database. Utah State History. Archived from the original on June 26, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ "The Pennsylvania State Memorial: Winfield Scott Hancock, (sculpture)". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "General Hancock". Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Soldiers and Sailors Monument, (sculpture)". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "Anne Hutchinson, (sculpture)". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "Governor William Bradford, (sculpture)". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "The Pioneer Mother". Markers and Monuments Database. Utah State History. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012.

- ^ The Protest Archived July 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine from Northeast Fine Arts.

- ^ "Protest, (sculpture)". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "Appeal To The Great Spirit, (sculpture)". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Tim Janicke, City of Art: Kansas City's Public Art (Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Star Books, 2001), p. 15. ISBN 0-9709131-8-4

- ^ Utah Museum of Fine Arts. "On the Warpath #28". Collections.umfa.utah.edu. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

External links

- Works by or about Cyrus Edwin Dallin at the Internet Archive

- Works from the Permanent Collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts at archive.today (archived December 12, 2012)

- List of sculptures by Cyrus Dallin in Massachusetts

- The Cyrus E. Dallin Art Museum, Arlington, Massachusetts

- Springville Museum of Art , Springville, Utah

- Biography from the Springville Museum of Art in Utah at the Wayback Machine (archived July 28, 2011)

- [1] from 1943 Class of Central High

- Cyrus Edwin Dallin

- 1861 births

- 1944 deaths

- 19th-century American sculptors

- 19th-century male artists

- 20th-century American sculptors

- 20th-century sculptors

- 20th-century male artists

- Académie Julian alumni

- American currency designers

- American male archers

- American male sculptors

- American Unitarians

- Angel Moroni

- Archers at the 1904 Summer Olympics

- Artists from Boston

- Coin designers

- Converts to Unitarianism

- Drexel University faculty

- Former Latter Day Saints

- Massachusetts College of Art and Design faculty

- Medalists at the 1904 Summer Olympics

- National Academy of Design members

- National Sculpture Society members

- Olympic bronze medalists for the United States in archery

- People from Arlington, Massachusetts

- People from Springville, Utah

- Sculptors from Massachusetts

- Sculptors from Utah