Awan dynasty: Difference between revisions

m Disambiguating links to Lost City (link changed to Lost city) using DisamAssist. |

|||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

According to the ''[[Sumerian King List]]'', a dynasty from Awan exerted hegemony in [[Sumer]] after defeating the [[First Dynasty of Ur]], probably in the 25th century BC.{{sfn|Kriwaczek|2010|p=136|ps=: "Then Urim was defeated and the kingship was taken to Awan."}} It mentions three Awan kings, who supposedly reigned for a total of 356 years.{{sfn|Legrain|1922|pp=[http://etana.org/sites/default/files/coretexts/14913.pdf 10–22]}} Their names have not survived on the extant copies, apart from the partial names of the second and third kings, "...Lu" and Ku-ul...", who it says ruled for 36 years.{{sfn|Stolper|1987}} This information is not considered reliable, but it does suggest that Awan had political importance in the 3rd millennium BC. |

According to the ''[[Sumerian King List]]'', a dynasty from Awan exerted hegemony in [[Sumer]] after defeating the [[First Dynasty of Ur]], probably in the 25th century BC.{{sfn|Kriwaczek|2010|p=136|ps=: "Then Urim was defeated and the kingship was taken to Awan."}} It mentions three Awan kings, who supposedly reigned for a total of 356 years.{{sfn|Legrain|1922|pp=[http://etana.org/sites/default/files/coretexts/14913.pdf 10–22]}} Their names have not survived on the extant copies, apart from the partial names of the second and third kings, "...Lu" and Ku-ul...", who it says ruled for 36 years.{{sfn|Stolper|1987}} This information is not considered reliable, but it does suggest that Awan had political importance in the 3rd millennium BC. |

||

A royal list found at [[Susa]] gives 12 names of the kings in the Awan dynasty.{{sfn|Hinz|1972}}{{sfn|Cameron|1936}}{{sfn|Vallat|1998}} The twelve kings of Awan given in the list are: [[Peli (king of Awan)|Pieli]], [[Tata (king of Awan)|Tari/ip]], [[Ukku-Tanhish|Ukkutahieš]], Hišur, Šušuntarana, Na-?-pilhuš, Kikkutanteimti, [[Luh-ishan|Luhhiššan]], Hišepratep, Hielu?, [[Khita|Hita-Idaddu-napir]], [[Puzur-Inšušinak]]. The twelve kings of the [[Shimashki Dynasty]] are: Girnamme, Tazitta, Ebarti, Tazitta, Lu?-x-luuhhan, [[Kindattu]], Idaddu, Tan-Ruhurater, Ebarti, Idaddu, Idaddu-Temti. |

A royal list found at [[Susa]] gives 12 names of the kings in the Awan dynasty.{{sfn|Hinz|1972}}{{sfn|Cameron|1936}}{{sfn|Vallat|1998}} The twelve kings of Awan given in the list are: [[Peli (king of Awan)|Pieli]], [[Tata (king of Awan)|Tari/ip]], [[Ukku-Tanhish|Ukkutahieš]], [[Hishutash|Hišur]], [[Shushun-Tarana|Šušuntarana]], [[Napi-Ilhush|Na-?-pilhuš]], [[Kikku-Siwe-Temti|Kikkutanteimti]], [[Luh-ishan|Luhhiššan]], Hišepratep, Hielu?, [[Khita|Hita-Idaddu-napir]], [[Puzur-Inšušinak]]. The twelve kings of the [[Shimashki Dynasty]] are: Girnamme, Tazitta, Ebarti, Tazitta, Lu?-x-luuhhan, [[Kindattu]], Idaddu, Tan-Ruhurater, Ebarti, Idaddu, Idaddu-Temti. |

||

As there are very few other sources for this period, most of these names are not certain. Little more of these kings' reigns is known, but Elam seems to have kept up a heavy trade with the Sumerian city-states during this time, importing mainly foods, and exporting cattle, wool, slaves and silver, among other things. A text of the time refers to a shipment of tin to the governor of the Elamite city of Urua, which was committed to work the material and return it in the form of bronze — perhaps indicating a technological edge enjoyed by the Elamites over the Sumerians. |

As there are very few other sources for this period, most of these names are not certain. Little more of these kings' reigns is known, but Elam seems to have kept up a heavy trade with the Sumerian city-states during this time, importing mainly foods, and exporting cattle, wool, slaves and silver, among other things. A text of the time refers to a shipment of tin to the governor of the Elamite city of Urua, which was committed to work the material and return it in the form of bronze — perhaps indicating a technological edge enjoyed by the Elamites over the Sumerians. |

||

Revision as of 16:40, 22 October 2024

| Awan dynasty Dynasty of Peli | |

|---|---|

| Dynasty | |

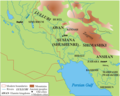

A map of the Near East detailing the geopolitical situation in the region during the Awan dynasty c. 2600 BC occupied by various contemporaneous archaeological cultures and/or civilizations such as those of the:

A clickable map of the present-day Islamic Republic of Iran detailing the locations of various ancient, archaeological sites, settlements, hamlets, villages, towns, and/or cities (and the approximated locations of six lost cities: Akkad, Akshak, Urua, Hidali, Hurti, and Kimash; also, the two lost capital cities of the Elamite Empire: Awan and Shimashki) that may have been visited, interacted and traded with, invaded, conquered, destroyed, occupied, colonized by and/or otherwise within the Elamites’ sphere of influence at some point temp. the dynasty of Awan. | |

| Parent family | Early Elamite kings |

| Country | Elam |

| Current region | Western Iran |

| Earlier spellings | lugal-e-ne a-wa-anki |

| Etymology | Kings of Awan |

| Place of origin | Asia |

| Founded | c. 2400 BC (c. 2600 BC) |

| Founder |

|

| Final ruler | Puzur-Inshushinak (r. c. 2100 BC) |

| Final head | Luh-ishan (d. c. 2325 BC) |

| Historic seat | Awan |

| Titles | |

| Connected families | Sukkalmah dynasty |

| Traditions | Elamite religion |

| Estate(s) | Godin Tepe |

| Dissolution | c. 2015 BC |

| Deposition | c. 2450 BC |

| Cadet branches | Shimashki dynasty |

The Elamites remained a major source of tension for the Sumerians, Akkadians, Amorites, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Kassites millennia after the supposed victory of the Awan dynasty over the first dynasty of Ur c. 2600 – c. 2340 BC as described on the Sumerian King List (SKL). | |

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

The Awan dynasty[a] was the first dynasty of Elam of which very little of anything is known today—appearing at the dawn of recorded history. The dynasty corresponds to the early part of the first Paleo-Elamite period (dated to c. 2400 – c. 2015 BC); additionally, succeeded by the Shimashki (c. 2200 – c. 1980 BC) and Sukkalmah dynasties (c. 1980 – c. 1450 BC).[1][2] The Elamites were likely major rivals of neighboring Sumer from remotest antiquity—they were said to have been defeated by Enmebaragesi of Kish c. 2750 BC—who is the earliest archaeologically attested king named on the Sumerian King List (SKL); moreover, by a later monarch, Eannatum of Lagash c. 2450 BC.[3] Awan was a city-state or possibly a region of Elam whose precise location is not certain; but, it has been variously conjectured conjectured to have been within the: Ilam and/or Fars provinces of what is today known as the Islamic Republic of Iran, to the north of Susa (in south Luristan), close to Dezful (in Khuzestan), or Godin Tepe (in the Kermanshah Province).[4][5][6]

History

Early Dynastic period (c. 2900 – c. 2350 BC)

According to the Sumerian King List, a dynasty from Awan exerted hegemony in Sumer after defeating the First Dynasty of Ur, probably in the 25th century BC.[7] It mentions three Awan kings, who supposedly reigned for a total of 356 years.[8] Their names have not survived on the extant copies, apart from the partial names of the second and third kings, "...Lu" and Ku-ul...", who it says ruled for 36 years.[9] This information is not considered reliable, but it does suggest that Awan had political importance in the 3rd millennium BC.

A royal list found at Susa gives 12 names of the kings in the Awan dynasty.[10][11][12] The twelve kings of Awan given in the list are: Pieli, Tari/ip, Ukkutahieš, Hišur, Šušuntarana, Na-?-pilhuš, Kikkutanteimti, Luhhiššan, Hišepratep, Hielu?, Hita-Idaddu-napir, Puzur-Inšušinak. The twelve kings of the Shimashki Dynasty are: Girnamme, Tazitta, Ebarti, Tazitta, Lu?-x-luuhhan, Kindattu, Idaddu, Tan-Ruhurater, Ebarti, Idaddu, Idaddu-Temti.

As there are very few other sources for this period, most of these names are not certain. Little more of these kings' reigns is known, but Elam seems to have kept up a heavy trade with the Sumerian city-states during this time, importing mainly foods, and exporting cattle, wool, slaves and silver, among other things. A text of the time refers to a shipment of tin to the governor of the Elamite city of Urua, which was committed to work the material and return it in the form of bronze — perhaps indicating a technological edge enjoyed by the Elamites over the Sumerians.

It is also known that the Awan kings carried out incursions in Mesopotamia, where they ran up against the most powerful city-states of this period, Kish and Lagash. One such incident is recorded in a tablet addressed to Enetarzi, a minor ruler or governor of Lagash, testifying that a party of 600 Elamites had been intercepted and defeated while attempting to abscond from the port with plunder.[13]

Akkadian period (c. 2350 – c. 2154 BC)

Events become a little clearer at the time of the Akkadian Empire (c. 2300 BC), when historical texts tell of campaigns carried out by the kings of Akkad on the Iranian plateau. Sargon of Akkad boasted of defeating a "Luh-ishan king of Elam, son of Hishiprashini", and mentions plunder seized from Awan, among other places. Luhi-ishan is the eighth king on the Awan king list, while his father's name "Hishiprashini" is a variant of that of the ninth listed king, Hishepratep - indicating either a different individual, or if the same, that the order of kings on the Awan king list has been jumbled.[14][15][9][1]

Sargon's son and successor, Rimush, is said to have conquered Elam, defeating its king who is named as Emahsini. Emahsini's name does not appear on the Awan king list, but the Rimush inscriptions claim that the combined forces of Elam and Warahshe, led by General Sidgau, were defeated at a battle "on the middle river between Awan and Susa". Scholars have adduced a number of such clues that Awan and Susa were probably adjoining territories.

With these defeats, the low-lying, westerly parts of Elam became a vassal of Akkad, centred at Susa. This is confirmed by a document of great historical value, a peace treaty signed between Naram-Sin of Akkad and an unnamed king or governor of Awan, probably Khita or Helu. It is the oldest document written in Elamite cuneiform that has been found.

Although Awan was defeated, the Elamites were able to avoid total assimilation. The capital of Anshan, located in a steep and mountainous area, was never reached by Akkad. The Elamites remained a major source of tension, that would contribute to destabilizing the Akkadian state, until it finally collapsed under Gutian pressure.

Gutian period (c. 2154 – c. 2112 BC)

When the Akkadian empire started to break down around 2240 BC, it was Kutik-Inshushinak (or Puzur-Inshushinak), the governor of Susa on behalf of Akkad, who liberated Awan and Elam, ascending to the throne.

By this time, Susa had started to gain influence in Elam (later, Elam would be called Susiana), and the city began to be filled with temples and monuments. Kutik-Inshushinak next defeated Kimash and Hurtum (neighboring towns rebelling against him), destroying 70 cities in a day. Next he established his position as king, defeating all his rivals and taking Anshan, the capital. Not content with this, he launched a campaign of devastation throughout northern Sumer, seizing such important cities as Eshnunna. When he finally conquered Akkad he was declared king of the four quarters, owner of the known world. Later, Ur-Nammu of Ur, founder of the 3rd dynasty of Ur defeated Elam, ending the dynasty of Awan.

Kutik-Inshushinak's work was not only as a conqueror; he created Elam's organization and the administrative structure. He extended the temple of Inshushinak, where he erected a statue of her.

After his defeat, the Awan dynasty disappears from history, probably cut down by the Guti or Lullubi tribes that then sowed disorder in Mesopotamia and the Zagros, and Elam was left in the hands of the Shimashki dynasty.

The toponym "Awan" only occurs once more following the reign of Kutik-Inshushinak, in a year-name of Ibbi-Sin of Ur. The name Anshan, on the other hand, which only occurs once before this time (in an inscription of Manishtushu), becomes increasingly more commonplace beginning with king Gudea of Lagash, who claimed to have conquered it around the same time. It has accordingly been conjectured that Anshan not only replaced Awan as one of the major divisions of Elam, but that it also included the same territory.[15]

List of rulers

The following list should not be considered complete:

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Dynastic IIIa period (c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC) | ||||||

| Awanite dynasty of Sumer (c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC) | ||||||

| ||||||

| 1st |

|

Unknown | Same person as Peli (?)[16] | Uncertain, fl. c. 2600 BC[17] | ||

| 2nd |

|

...Lu | Same person as Tata (?)[16] | Uncertain, fl. c. 2580 BC[18] |

| |

| 3rd |

|

Kur-Ishshak 𒆪𒌌 |

Same person as Ukku-Tanhish (?)[16] | Uncertain, fl. c. 2550 BC (36 years) |

| |

| ||||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2500 – c. 2350 BC) | ||||||

| Dynasty of Peli (c. 2500 – c. 2015 BC) | ||||||

| 1st |

|

Peli or Feyli | Founder | Uncertain, fl. c. 2500 BC |

| |

| 2nd | Tata 𒋫𒀀𒅈 |

Same person as ...Lu (?)[16] | Uncertain, fl. c. 2450 BC[16] |

| ||

| 3rd | Ukku-Tanhish | Same person as Kur-Ishshak (?)[16] | Uncertain, fl. c. 2430 BC[16] |

| ||

| 4th | Hishutash | Uncertain, fl. c. 2400 BC[16] |

| |||

| 5th | Shushun-Tarana 𒋗𒋗𒌦𒋫𒊏𒈾 |

Uncertain, fl. c. 2380 BC[12] |

| |||

| 6th | Napi-Ilhush 𒈾𒉿𒅍𒄷𒄷 |

Uncertain, fl. c. 2360 BC |

| |||

| 7th | Kikku-Siwe-Temti | Uncertain, fl. c. 2350 BC |

| |||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Proto-Imperial period (c. 2350 – c. 2334 BC) | ||||||

| 8th |

|

Luh-ishan 𒇻𒄴𒄭𒅖𒊮𒀭 |

Son of Ḫišibrasini[9] | Uncertain, d. c. 2325 BC[16] | ||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Akkadian period (c. 2334 – c. 2154 BC) | ||||||

| 9th |

|

Hishep-Ratep I | Same person as Ḫišibrasini (?)[16] | Uncertain, fl. c. 2320 BC[16] |

| |

| 10th | Helu | Uncertain, fl. c. 2300 BC[16] |

| |||

| 11th |

|

Khita 𒄭𒋫𒀀 |

Same person as Hita'a (?)[16] | Uncertain, reigned c. 2220 BC[16] |

| |

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Gutian period (c. 2154 – c. 2112 BC) | ||||||

| 12th |

|

Puzur-Inshushinak 𒅤𒊭𒀭𒈹𒂞 |

Son of Shinpi-hish-huk | Uncertain, r. c. 2150 BC[16] |

| |

Gallery

-

The Susanian Dynastic List—a regnal list dated to c. 1800 – c. 1600 BC and provenanced at Susa. Its current location is the Louvre Museum, Sb 17729. It names twelve kings for Awan and another twelve for Shimashki.[19][20]

-

A God putting a foundation nail in the ground, protected by a Lama goddess, in front of a roaring lion. Coiled snake on top. Inscriptions in Linear Elamite and Akkadian. Time of Kutik-Inshushinak, circa 2100 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Statue of goddess Narundi dedicated by Awan king Kutik-Inshushinak, with inscriptions in Linear Elamite and in Akkadian, circa 2100 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Bilingual Linear Elamite-Akkadian inscription of king Kutik-Inshushinak, "Table of the Lion", Louvre Museum Sb 17

See also

- Elam

- Awan (ancient city)

- Shimashki dynasty

- Sukkalmah dynasty

- List of rulers of Elam

- List of Assyrian kings

- List of kings of Babylon

- Sumerian King List

- List of kings of Akkad

- List of rulers of the pre-Achaemenid kingdoms of Iran

- List of monarchs of Persia

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b Leick 2001, p. 99.

- ^ Ir 2015b.

- ^ Gershevitch 1985, p. 25–26.

- ^ Liverani 2013, p. 142.

- ^ Hansen & Ehrenberg 2002, p. 233.

- ^ Kriwaczek 2010, p. 136: "Then Urim was defeated and the kingship was taken to Awan."

- ^ Legrain 1922, pp. 10–22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stolper 1987.

- ^ Hinz 1972.

- ^ Cameron 1936.

- ^ a b Vallat 1998.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 331.

- ^ Scheil 1931.

- ^ a b Hansman 1985.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kessler 2021.

- ^ Majidzadeh 1997.

- ^ Majidzadeh 1991.

- ^ "Awan King List".

- ^ SCHEIL, V. (1931). "Dynasties Élamites d'Awan et de Simaš". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 28 (1): 1–46. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23283945.

Sources

Bibliography

- Cameron, George (1936). History of Early Iran (Thesis). United States: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780608165332.

- Diakonoff, I. (1956). История Мидии От Древнейших Времен До Конца IV Века До Н.э. [The history of Media from ancient times to the end of the 4th century BCE] (in Russian). Moscow and Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences.

- Ir, E (2015a). "SUSA". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Ir, E (2015b). "SUSA ii. HISTORY DURING THE ELAMITE PERIOD". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Gershevitch, I. (1985) [1968]. The Median and Achaemenian periods. The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521200912.

- Hansen, D.; Ehrenberg, E. (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060552.

- Hansman, J. (1985). "Anshan". Encyclopædia Iranica. 1. Vol. II. pp. 103–107.

- Hayes, W.; Rowton, M.; Stubbings, F. (1964). "VII". Chronology. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. I (Revised ed.). Bureau of Military History: CUP (published 1961).

- Hinz, W. (1972). Written at United Kingdom. The Lost World of Elam: Re-creation of a Vanished Civilization. Translated by Barnes, J. University of California: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 9780283978630.

- Jacobsen, T. (1939). The Sumerian King List (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Oriental Institute. ISBN 9780226622736.

- Kramer, S. (1963). The Sumerians: their history, culture, and character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226452388. LCCN 63011398.

- Kriwaczek, P. (2010). Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781429941068.

- Legrain, L. (1922). Historical Fragments. Vol. XIII. United States: University of Pennsylvania Museum. ISBN 9780598776341.

- Leick, G. (2001). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. Who's Who series. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415132312.

- Liverani, M. (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 9781134750849.

- Majidzadeh, Y. (1991). تاريخ و تمدن ايلام [History and civilization of Elam] (in Persian). Iran: University of Tehran Press.

- Majidzadeh, Y. (1997). تاريخ و تمدن بين النهرين [History and civilization of Mesopotamia] (in Persian). Vol. 1. Iran: University of Tehran Press. ISBN 9789640108413.

- Potts, D. (1999-07-29). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian State (1st ed.). Cambridge, UK; New York, US: Cambridge University Press (published 1999–2016). ISBN 9780521563581.

- Stolper, M. (1987). "AWAN". Encyclopædia Iranica. 2. Vol. III. pp. 113–114.

- Vallat, F. (1998). "ELAM i. The history of Elam". Encyclopædia Iranica. 3. Vol. VIII. pp. 301–313.

Journals

- Scheil, V. (1931). "Dynasties Élamites d'Awan et de Simaš". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 28 (1). Presses Universitaires de France: 1–46. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23283945.

External links

- Dahl, J. (2012-07-24). "Rulers of Elam". cdliwiki: Educational pages of the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI).

- Jacobsen, T. (1939b). Zólyomi, G.; Black, J.; Robson, E.; Cunningham, G.; Ebeling, J. (eds.). "Sumerian King List". ETCSL. Translated by Glassner, J.; Römer, W.; Zólyomi, G. (revised ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford.

- Kessler, P. (2021). "Kingdoms of Iran - Elam / Haltamtu / Susiana". The History Files. Kessler Associates.

- Langdon, S. (1923). "W-B 444". CDLI. Ashmolean Museum.

- Lendering, J. (2006). "Sumerian King List".

Further reading

Language

- Black, Jeremy Allen; Baines, John Robert; Dahl, Jacob L.; Van De Mieroop, Marc (2024). Cunningham, Graham; Ebeling, Jarle; Flückiger-Hawker, Esther; Robson, Eleanor; Taylor, Jon; Zólyomi, Gábor (eds.). "ETCSL: The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Faculty of Oriental Studies (revised ed.). United Kingdom.

The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL), a project of the University of Oxford, comprises a selection of nearly 400 literary compositions recorded on sources which come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and date to the late third and early second millennia BCE.

- Renn, Jürgen; Dahl, Jacob L.; Lafont, Bertrand; Pagé-Perron, Émilie (2024). "CDLI: Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative".

Images presented online by the research project Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI) are for the non-commercial use of students, scholars, and the public. Support for the project has been generously provided by the Mellon Foundation, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the Institute of Museum and Library Services (ILMS), and by the Max Planck Society (MPS), Oxford and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); network services are from UCLA's Center for Digital Humanities.

- Sjöberg, Åke Waldemar; Leichty, Erle; Tinney, Steve (2024). "PSD: The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary".

The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary Project (PSD) is carried out in the Babylonian Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. It is funded by the NEH and private contributions. [They] work with several other projects in the development of tools and corpora. [Two] of these have useful websites: the CDLI and the ETCSL.

![The Susanian Dynastic List—a regnal list dated to c. 1800 – c. 1600 BC and provenanced at Susa. Its current location is the Louvre Museum, Sb 17729. It names twelve kings for Awan and another twelve for Shimashki.[19][20]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Dynastic_list_Awan_Siwashi_Louvre_Sb17729.jpg/96px-Dynastic_list_Awan_Siwashi_Louvre_Sb17729.jpg)