Adelle Davis: Difference between revisions

Anastrophe (talk | contribs) →Modern influence and critics: reiteration is unnecessary. further assorted c/e |

Anastrophe (talk | contribs) →Quotes: distractingly formatted. simplify. |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

==Quotes== |

==Quotes== |

||

| ⚫ | Davis is known for the quote "Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince and dinner like a pauper."<ref>{{Cite journal|date=2017-07-01|title=Breakfast: The most important meal of the day?|journal=International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science|language=en|volume=8|pages=1–6|doi=10.1016/j.ijgfs.2017.01.003|issn=1878-450X|last1=Spence|first1=Charles|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite magazine|url=http://time.com/4408772/best-times-breakfast-lunch-dinner/|title=When To Eat Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner|magazine=Time|language=en|access-date=2018-10-04}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.diabetes.org.sg/resources/0412-eat.pdf|title=EAT BREAKFAST LIKE A KING|last=Chiang|first=Zoe, dietitian, NHG Polyclinics|website=diabetes.org.sg|access-date=4 October 2018|archive-date=12 October 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151012150903/http://www.diabetes.org.sg/resources/0412-eat.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://portal.nifa.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/1004662-to-eat-breakfast-like-a-king-lunch-like-a-prince-and-dinner-like-a-pauper--testing-the-relationship-between-meal-proportions-and-obesity.html|title=To eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper?" --Testing the Relationship between Meal Proportions and Obesity - UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT|website=portal.nifa.usda.gov|access-date=2018-10-05}}</ref> |

||

Adelle Davis is known for: |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==Private life== |

==Private life== |

||

Revision as of 19:14, 22 October 2024

Adelle Davis | |

|---|---|

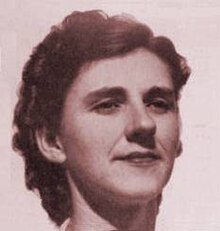

Davis, c. 1925 | |

| Born | Daisie Adelle Davis February 25, 1904 Lizton, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | May 31, 1974 (aged 70) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Nutritionist, author |

| Known for | Let's Cook it Right (1947); Let's Have Healthy Children (1951, 1972); Let's Eat Right to Keep Fit (1954, 1970); Let's Get Well (1965) |

| Website | The Adelle Davis Foundation |

Adelle Davis (25 February 1904 – 31 May 1974) was an American writer and nutritionist, considered "the most famous nutritionist in the early to mid-20th century."[1]: 150 She was an advocate for improved health through better nutrition. She wrote an early textbook on nutrition in 1942, followed by four best-selling books for consumers which praised the value of natural foods and criticized the diet of the average American. Her books sold over 10 million copies and helped shape America's eating habits.

Despite her popularity, she was heavily criticized by her peers for many recommendations she made that were not supported by the scientific literature, some of which were considered dangerous.

Early years and education

Adelle Davis was born on February 25, 1904, on a small-town farm near Lizton, Indiana.[2] She was the youngest of five daughters of Charles Eugene Davis and Harriette (McBroom) Davis.[2]

When she was ten days old, her mother was paralyzed from a stroke and died seventeen months later.[2] Because bottle feeding was then unknown, Davis had to be fed with an eye-dropper, and later felt her interest in nutrition was due to the deprivation of oral feeding during her infancy.[2] Early in her career she treated every patient as if they were herself. "Every patient was me, and I was mother, trying to get him healthy. I spent all my time making up for the mother I didn't have."[3]

She was raised with her sisters on the family's farm by her father and an elderly aunt, where among her duties were pitching hay, plowing corn fields, and milking cows.[2] She rode seven miles in a horse and buggy to attend school, where she graduated in 1923 with thirteen other students.[2] From age ten to eighteen, she was also an active member of the 4-H Club, an organization which helped youths reach their fullest potential.[2] During her time with the club she won numerous ribbons for her breads, canned fruits and vegetables, which she had entered at state and county fairs.[2]

She enrolled at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana where she stayed from 1923 to 1925, majoring in home economics.[4] To help pay for college costs she worked at various jobs, and played tennis in her free time.[2] During the summers she stayed active with the 4-H Club as a club leader.[2] After two years at Purdue she transferred to the University of California at Berkeley, where she graduated in 1927 with a degree in dietetics.[2][5] Berkeley had set up the first department of nutrition in America in 1912.[6]

Career as a nutrition expert

After receiving further dietetic training at Bellevue and Fordham Hospitals in New York City from 1927 to 1928, she supervised nutrition for Yonkers Public Schools and consulted as a nutritionist for New York obstetricians.[5] In 1928 she also worked as a nutritionist at the Judson Health Center in Manhattan. After working at hospitals where she set up diets for patients, she decided to not take on any more hospital assignments as she wanted to work more closely with each individual patient.[2] In the fall of 1928 she enrolled in postgraduate studies at Teachers College, Columbia University[7] and then took some time off to travel around Europe.[2]

After returning from Europe, Davis moved to Oakland, California in 1931 and worked as a consulting nutritionist for doctors at the Alameda County Health Clinic.[2] Two years later she moved to Los Angeles to do consulting at a medical clinic in Hollywood.[2] She also enrolled at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles where she earned a master of science degree in biochemistry, in 1938.[5] She worked as a consulting nutritionist in Oakland and then in Los Angeles with physicians at the Alameda County Health Clinic and the William E. Branch Clinic in Hollywood. She also prescribed diets to the patients that were referred to her by numerous specialists.[8]

To help her spread nutrition information to the public she took a writing course and began writing pamphlets and books.[2] She continued seeing patients referred to her by physicians,[2] and by the end of her career she had helped approximately 20,000 referred patients.[7] She had practiced professional nutritional counseling for 35 years before she retired and devoted her time to her family.[9]

Career as nutritionist and author

After writing a promotional pamphlet for a milk company in 1932, she wrote two non-published treatises: Optimum Health (1935) and You Can Stay Well (1939). In 1942 Davis wrote a 524-page, forty-one chapter nutrition textbook for Macmillan, Inc., Vitality Through Planned Nutrition. But she received public acclaim with her subsequent books written for the general public: Let's Cook it Right (1947); Let's Have Healthy Children (1951); Let's Eat Right to Keep Fit (1954); and Let's Get Well (1965).[5][10] By 1974, when she died, her books had sold over 10 million copies.[11]

Davis wrote her consumer books over a 40-year career, revising some in the 1970s. She saw herself as an "interpreter", not merely a researcher. "I think of myself as a newspaper reporter, who goes out to libraries and gathers information from hundreds of journals, which most people can't understand, and I write it so that people can understand." She reviewed scientific literature in the biochemical libraries at U.C.L.A., for instance. Her references for Let's Get Well totaled almost 2,500, many from cases during her nutrition practice, and she was upset when the publisher of Let's Have Healthy Children eliminated the 2,000 references from the 1972 revision, according to author Daniel Yergin.[3]

Her first book, Let's Cook it Right (1947), was an effort to update and improve on the popular guide, Joy of Cooking (1931), by including scientific facts about nutrition.[2] Besides giving various new recipes, she instructs the housewife in how to enrich recipes with nutritious ingredients such as powdered milk and wheat germ, and describes how to best preserve flavors and nutrients when cooking.[2]

This book, like her later ones, was aimed at educating readers. She promoted the benefits of whole grains and breads, fresh vegetables, vitamin supplements, limits on sugar, and avoidance of packaged and processed foods.[1]: 2

The book was well received and she went on to publish Let's Have Healthy Children (1951; revised in 1972 and 1981), which drew on her own experiences of working with obstetricians and conducting her own research.[2] The book offers nutrition advice for pregnant women as well as for infants and young children, including explaining the benefits of breastfeeding and when to introduce solid foods.[2]

She denounced prepared baby foods due to their high concentrations of additives and pesticide residue, which made her opinions controversial among doctors.[12] In the book she also criticized obstetricians and pediatricians for being ignorant about nutrition, which leads them to prescribe harmful diets for both mother and child. She said that "the chapter on canned foods will make your hair stand on end".[12]

She argued that women who did not eat well during pregnancy were more likely to suffer from numerous medical problems and that their infants might have hearing and vision abnormalities, rickets and anemia, and do poorly in school, and that such mothers were settling for mediocre children when they could have superior ones.[13]

Her third book was Let's Eat Right to Keep Fit (1954; updated 1970), which was written as a basic primer on nutrition for the layperson. In it she includes numerous documented case histories from her practice and from footnoted medical journals.[2] She explained the functions of, and food sources for, over forty nutrients considered essential to human health, including vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, and proteins.[2]

She also described in detail her belief that most Americans inflicted harm on themselves with their typical diets, which was excessively high in salt, refined sugars, pesticides, growth hormones, preservatives and other additives, and thereby "devitalized" of its essential nutrients by the excessive processing. As a result, she suggested that countless adults and most children in the U.S. "have never once had a mouthful of genuinely wholesome food".[2] She recognizes that wholesome foods are difficult to obtain in supermarkets, which is one of the reasons she recommended vitamin supplements.[2]

Although she was not a vegetarian, and ate moderate amounts of pork, veal and fish, she did not shy away from stating that "The great American Hamburger has done tremendous harm to health," and added that "for the great American charcoal-broiled steak, I wouldn't go across the street for one." She explained that beef is fattened with synthetic female hormones which "adds water weight, not protein weight". Besides believing it contributed to cancer, she said it also harmed men's virility: "I'm amazed there are any functioning males in this country of steak eaters."[12]

Some reviews of the book were highly critical, one reviewer saying it was "replete with misinformation" and an example of books which promotes "food fads and cults rather than soundly established nutrition information and practice.[14] Another stated that Davis "indulges in amateur diagnosis which is both unconvincing and dangerous ... which cannot be recommended because of its inaccuracies and the over-dramatic manner in which the material is presented."[15]

Let's Get Well (1965) was her final book, in which she tried to convince the reader that before most diseases develop there were likely nutritional deficiencies that people were not aware of. She discussed nutritional therapy for hundreds of ailments, including heart disease, high cholesterol, ulcers, diabetes, and arthritis, often contradicting the dietary advice given by many physicians. The book is documented with over 2,000 footnoted references to studies reported in medical journals and books.[2] In her book Exploring Inner Space which was published in 1961 under the name of Jane Dunlap, she described her experience in taking the hallucinogenic drug LSD.[16]

Social concerns about nutrition

Davis believed many of America's dietary problems were due to most doctors not being well informed about nutrition. She believed few medical schools offered nutrition courses and physicians had little time to read the hundreds of medical journals published to keep up with new findings.[2]

Davis criticized the food industry for promoting bad eating habits with misleading advertising. "It's just propaganda," she said, "that the American diet is the best in the world. Commercial people have been telling us those lies for years."[12] In a television interview she said that a "great deal of sickness is caused by refined foods". She states that "We are literally at the mercy of the unethical refined food industry, who take all the vitamins and minerals out of food."[4]

She was also worried about the welfare of society in general, warning in 1973 that "nutrition consciousness had better grow or we're going under...We're watching the fall of Rome right now, very definitely, because Americans are getting more than half their calories from food with no nutrients. People are exhausted."[3] In her opinion, according to Yergin, "entire civilizations rise and fall on their diets".[3] She felt that one of the reasons Germany easily defeated France in World War II was due to the Germans' healthier diets. "Ominously, she warns that the Russians eat much less of the illness-breeding refined foods than do Americans."[3]

Public appearances

Davis's works gained further popularity from speaking on the lecture circuit on college campuses as well as in Latin America and Europe, and she eventually became sought after for guest appearances on television talk shows.

Modern influence and critics

Although her ideas were considered somewhat eccentric in the 1940s and 1950s, the change in culture with the 1960s brought her ideas, especially her anti-food processing and food industry charges, into the mainstream in a time when anti-authority sentiment was growing.[17] One historian described Davis as the "most widely read nutritionist of the postwar decades ... [whose work] helped to shape Americans' eating habits, their child-feeding practices, their views about the quality of their food supply, and their beliefs about the impact of nutrition on their emotional and physical health."[18]

Physician Robert C. Atkins, who promoted the Atkins diet, said Davis' books had contributed to his own pursuit of nutrition in medicine.[19]

Davis also contributed to, as well as benefiting from, the rise of a nutritional and health-food movement that began in the 1950s, which focused on subjects such as pesticide residues and food additives,[5] a movement her critics would come to term food faddism.[20] During the 1960s and 1970s, her popularity continued to grow, as she was featured in multiple media reports, variously described as an "oracle" by The New York Times and a "high priestess" by Life, and was compared to Ralph Nader, the popular consumer activist, by the Associated Press. Her celebrity was demonstrated by her repeated guest appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, as she became the most popular and influential nutritionist in the country.[17]

A significant portion of Davis's appeal came from her credentials, including her university training, and her apparent application of scientific studies and principles to her writing, with one book totaling over 2100 footnotes and citations.[17] Some of her nutritional ideas, such as the need for exercise, the dangers of vitamin deficiencies,[5] and the need to avoid hydrogenated fat, saturated fat, and excess sugar, remain relevant even to modern nutritionists.[17] U.S. Senator Patrick Leahy commended her views in 1998 as well, in remarks supporting a law protecting free speech on food safety from the threat of lawsuits.[21]

Although she was very popular with the public in general in the 1970s, none of her books were recommended by any significant nutritional professional society of the time. Independent review of the superficially impressive large number of citations to the scientific literature in her books found that the citations often either misquoted the scientific literature or were contradicted by or unsupported by the proposed citation, and that errors in the book averaged at least one per page.[22] One review noted that only 30 of 170 citations in a sample taken from one chapter accurately supported the assertions in her book.[17] The 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health labelled her as probably the single most harmful source of false nutritional information.[5][23]

A nutritionist in a literature review said that her works were "at best a half truth" or led to "ridiculous conclusions".[20] Nutritionists disputed her view that alcoholism, crime, suicide, and divorce were byproducts of poor diet.[17][12]

Her reliance on supplements led in a few instances to lawsuits asserting that her recommendations caused children harm. The litigation was ultimately settled out of court.[24][17][25]

Much of her advice was inaccurate, and some of it was harmful. For example, "she recommended magnesium as a treatment for epilepsy, potassium chloride for certain patients with kidney disease, and megadoses of vitamins A and D for other conditions." There was a case with a four-year-old who was hospitalized at the University of California Medical Center in San Francisco. The child was pale and chronically ill because her mother, who was an adherent of Davis's nutrition, was giving her large doses of vitamins A and D plus calcium lactate.[16]

Quotes

Davis is known for the quote "Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince and dinner like a pauper."[26][27][28][29]

Private life

In October 1943, Davis married George Edward Leisey, and adopted his two children, George and Barbara, though she never had children of her own.[17] She divorced George Leisey in 1953 and married a retired accountant and lawyer named Frank Sieglinger in 1960.[5]

In 1973 she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma and later died of the same disease in 1974 in her home at the age of seventy.[5] She attributed her getting cancer to her early years in college, where she ate junk food before learning about its negative effects on health, and to a number of X-rays she underwent. Before her death she stated, "In my opinion there is no question whatsoever that the terrific amount of cancer we have now is related to the inadequacies of our American diet."[30]

Honors and awards

- 1972, honorary Doctor of Science, Plano University, Texas

- 1972, Raymond A. Dart Human Potential Award, presented by the Steelworkers of America

Publications

Books on nutrition:

- Optimum Health (1935)

- You Can Stay Well (1939)

- Vitality Through Planned Nutrition (1942)

- Let's Cook it Right (1947) ISBN 4-87187-958-5

- Let's Have Healthy Children (1951), ISBN 0-451-05346-X

- Let's Eat Right to Keep Fit (1954) ISBN 4-87187-961-5

- ALONG THE BACKROADS OF EUROPE, Nutrition Early RARE Pamphlet Travel, (c. late 1950s). Published by N.P. Plus Products.

- Let's Get Well (1965), ISBN 0-15-150372-9

- You Can Get Well (1975). Published by Benedict Lust Pubns (June 1, 1975). ISBN 978-0879040338

- Let's Stay Healthy: A Guide to Lifelong Nutrition, (1981). Published by Harcourt; Subsequent edition (December 1, 1981) ISBN 978-0151504435

Other publications:

- Exploring Inner Space: Personal Experiences Under LSD-25 (1961) - published under the pen name Jane Dunlap, describing her experience with LSD.[12] ISBN 9784871879606

- Georgia's Girls: In the Beginning (2015), published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN 1523932074

References

- ^ a b Bissonnette, David (2014). It's All about Nutrition: Saving the Health of Americans. University Press of America. ISBN 9780761863809. Retrieved 31 July 2019 – via Google Books.

The suspicion that our diet as a nation was making us sick, certainly began with the early books of Adelle Davis, who became the most famous nutritionist in the early to mid-20th century.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Moritz, Charles, ed. Current Biography Yearbook: 1973, The H. W. Wilson Co. N.Y. (1974) pp. 93-95 (OCLC 9236087, 781401309)

- ^ a b c d e Yergin, Daniel. "Let's Get Adelle Davis Right", New York Times, May 20, 1973

- ^ a b TV interview with Adelle Davis, Associated Press

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sicherman, Barbara, ed. Notable American Women: The Modern Period : a Biographical Dictionary, Harvard Univ. Press (1980) pp. 179-180

- ^ Shurtleff, William. Origin and Early History of Peanut Butter (1884-2015), Soyinfo Center (2015) p. 91

- ^ a b "Two Readers Credit Adelle Davis for Their Good Health", The Cincinnati Enquirer, April 5, 1972

- ^ An Outspoken Believer Retrieved on 8 Mar 2018

- ^ Adelle Davis Remembered: The Mother of Nutrition Retrieved on 8 Mar 2018

- ^ Smith, Andrew. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Volume 2, Oxford Univ. Press (2012) pp. 607-608

- ^ Zoumbaris, Sharon. Nutrition, ABC-CLIO textbook (2009) p. 9

- ^ a b c d e f Howard, Jane. "Earth Mother to the Foodists", Life magazine, Oct. 22, 1971 pp. 67-70

- ^ Iacovetta, Franca. Edible Histories, Cultural Politics: Towards a Canadian Food History, Univ. of Toronto Press (2012) ebook

- ^ Shank RE. Let's "Eat Right to Keep Fit" American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health 1955;45(9):1176.

- ^ "Let's Eat Right to Keep Fit" California Medicine 1955;82(3):207-208.

- ^ a b "The Legacy of Adelle Davis". www.quackwatch.org. 13 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hurley, Dan (2006). Natural causes: death, lies, and politics in America's vitamin and herbal supplement industry. Random House. ISBN 978-0-7679-2636-2.

- ^ Carstairs, Catherine. "'Our Sickness Record Is a National Disgrace': Adelle Davis, Nutritional Determinism, and the Anxious 1970s", J Hist Med Allied Sci (2014) 69 (3): 461-491

- ^ Atkins, Robert C. Dr. Atkins' Vita-nutrient Solution: Nature's Answers to Drugs, Simon & Schuster (1998) p. 26

- ^ a b McBean LD, Speckmann EW (October 1974). "Food faddism: a challenge to nutritionists and dietitians". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 27 (10): 1071–8. doi:10.1093/ajcn/27.8.1071. PMID 4417113.

- ^ Leahy, Patrick (April 29, 1998). "Statement of Senator Patrick Leahy on The First Amendment and Food Safety". Center for Science in the Public Interest. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ Rynearson EH (July 1974). "Americans love hogwash". Nutr. Rev. 32: suppl 1:1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1974.tb05179.x. PMID 4367657.

- ^ Stephen Barrett (October 13, 2006). "The Legacy of Adelle Davis". Quackwatch. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ Herbert V (April 1982). "Legal aspects of specious dietary claims". Bull N Y Acad Med. 58 (3): 242–53. PMC 1805329. PMID 6956409.

- ^ Shils, Maurice (1999). Modern nutrition in health and disease. Williams & Wilkins. p. 1797. ISBN 0-7817-4133-5.

- ^ Spence, Charles (2017-07-01). "Breakfast: The most important meal of the day?". International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science. 8: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2017.01.003. ISSN 1878-450X.

- ^ "When To Eat Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner". Time. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- ^ Chiang, Zoe, dietitian, NHG Polyclinics. "EAT BREAKFAST LIKE A KING" (PDF). diabetes.org.sg. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "To eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper?" --Testing the Relationship between Meal Proportions and Obesity - UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT". portal.nifa.usda.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ^ "Nutrition Advocate Dies at 70", Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), June 1, 1974

External links

- The Adelle Davis Foundation

- Wetli CV, Davis JH. Fatal hyperkalemia from accidental overdose of potassium chloride. JAMA 240:1339, 1978.

- Schlesinger B, Payne B, Black J. Potassium metabolism in gastroenteritis. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 24:33-49, 1955.

- Potassium metabolism in gastroenteritis. Nutrition Reviews 14: 295-296, 1956.

- 1904 births

- 1974 deaths

- American women nutritionists

- American nutritionists

- American health activists

- Deaths from multiple myeloma in California

- University of California, Berkeley alumni

- American health and wellness writers

- American women non-fiction writers

- Diet food writers

- Pseudoscientific diet advocates

- Psychedelic drug researchers

- American women food writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American women writers

- People from Palos Verdes Estates, California

- Activists from Indiana

- Activists from California