Assassination of John F. Kennedy: Difference between revisions

→Autopsy: link |

Bimerfatih (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| timezone = [[Central Standard Time|CST]] |

| timezone = [[Central Standard Time|CST]] |

||

| weapons = {{ubl|[[John F. Kennedy assassination rifle|6.5×52mm Italian Carcano M91/38 rifle]] (Kennedy)|[[John F. Kennedy assassination rifle#Revolver|.38 cal Smith & Wesson Victory Model revolver]] (Tippit)}} |

| weapons = {{ubl|[[John F. Kennedy assassination rifle|6.5×52mm Italian Carcano M91/38 rifle]] (Kennedy)|[[John F. Kennedy assassination rifle#Revolver|.38 cal Smith & Wesson Victory Model revolver]] (Tippit)}} |

||

| fatalities = {{ubl|John F. Kennedy|[[J. D. Tippit]]}} |

| fatalities = {{ubl|[[John F. Kennedy]]|[[J. D. Tippit]]}} |

||

| injuries = {{ubl|[[John Connally]]|[[James Tague]]}} |

| injuries = {{ubl|[[John Connally]]|[[James Tague]]}} |

||

| perp = [[Lee Harvey Oswald]] |

| perp = [[Lee Harvey Oswald]] |

||

Revision as of 09:33, 23 October 2024

| Assassination of John F. Kennedy | |

|---|---|

President John F. Kennedy, his wife Jacqueline, Texas governor John Connally, and Connally's wife Nellie in the presidential limousine minutes before the assassination in Dallas | |

| |

| Location | Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 32°46′45.4″N 96°48′30.6″W / 32.779278°N 96.808500°W |

| Date | November 22, 1963 12:30 p.m. (CST) |

| Target | John F. Kennedy |

| Weapons | |

| Deaths | |

| Injured | |

| Perpetrator | Lee Harvey Oswald |

| Charges | Murder with malice (2 counts, murdered before trial) |

On November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. Kennedy was in the vehicle with his wife Jacqueline, Texas Governor John Connally, and Connally's wife Nellie, when he was fatally shot from the nearby Texas School Book Depository by Lee Harvey Oswald, a former U.S. Marine. The motorcade rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where Kennedy was pronounced dead about 30 minutes after the shooting; Connally was also wounded in the attack but recovered. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was hastily sworn in as president two hours and eight minutes later aboard Air Force One at Dallas Love Field.

After the assassination, Oswald returned home to retrieve a pistol; he shot and killed lone Dallas policeman J. D. Tippit shortly afterwards. Around 70 minutes after Kennedy and Connally were shot, Oswald was apprehended by the Dallas Police Department and charged under Texas state law with the murders of Kennedy and Tippit. Two days later, at 11:21 a.m. on November 24, 1963, as live television cameras covered Oswald's being moved through the basement of Dallas Police Headquarters, he was fatally shot by Dallas nightclub operator Jack Ruby. Like Kennedy, Oswald was taken to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where he soon died. Ruby was convicted of Oswald's murder, though the decision was overturned on appeal, and Ruby died in prison in 1967 while awaiting a new trial.

After a 10-month investigation, the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald assassinated Kennedy, and that there was no evidence that either Oswald or Ruby was part of a conspiracy. In 1967, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison brought the only trial for Kennedy's murder, against businessman Clay Shaw; Shaw was acquitted. Subsequent federal investigations—such as the Rockefeller Commission and Church Committee—agreed with the Warren Commission's general findings. In its 1979 report, the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) concluded that Kennedy was likely "assassinated as a result of a conspiracy". The HSCA did not identify possible conspirators, but concluded that there was "a high probability that two gunmen fired at [the] President". The HSCA's conclusions were largely based on a police Dictabelt recording later debunked by the U.S. Justice Department.

Kennedy's assassination is still the subject of widespread debate and has spawned many conspiracy theories and alternative scenarios; polls found that a vast majority of Americans believed there was a conspiracy. The assassination left a profound impact and was the first of four major assassinations during the 1960s in the United States, coming two years before the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, and five years before the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Kennedy's brother Robert in 1968. Kennedy was the fourth U.S. president to be assassinated and is the most recent to have died in office.

Background

Kennedy

In 1960, John F. Kennedy, then a U.S. senator from Massachusetts, was elected the 35th president of the United States with Lyndon B. Johnson as his vice presidential running mate.[1][2][3][4] Kennedy's tenure saw the height of the Cold War, and much of his foreign policy was dedicated to countering the Soviet Union and communism.[5][6] As president, he authorized operations to overthrow Fidel Castro's communist government in Cuba,[7] which culminated in the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961, during which he declined to directly involve American troops.[8] The following year, Kennedy deescalated the Cuban Missile Crisis, an incident widely regarded as the closest that humanity has come to nuclear holocaust.[9]

In 1963, Kennedy decided to travel to Texas to smooth over frictions in the state's Democratic Party between liberal U.S. Senator Ralph Yarborough and conservative Governor John Connally.[10][11] The visit was first agreed upon by Kennedy, Johnson, and Connally during a meeting in El Paso in June.[12] The motorcade route was finalized on November 18 and announced soon thereafter.[13] Kennedy also viewed the Texas trip as an informal launch of his 1964 reelection campaign.[14]

Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (born 1939)[17] was a former U.S. Marine who had served in Japan and the Philippines and had espoused communist beliefs since reading Karl Marx aged 14.[18][19][20] After accidentally shooting his elbow with an unauthorized handgun and fighting an officer, Oswald was court-martialed twice and demoted.[19] In September 1959, he received a dependency discharge after claiming his mother was disabled.[21] A 19-year-old Oswald sailed on a freighter from New Orleans to France and then traveled to Finland, where he was issued a Soviet visa.[22]

Oswald defected to the Soviet Union,[23][note 2] and in January 1960 he was sent to work at a factory in Minsk, Belarus.[26][27] In 1961, he met and married Marina Prusakova,[28] with whom he had a child.[29] In 1962, he returned to the United States with a repatriation loan from the U.S. Embassy.[29] He settled in the Dallas/Fort Worth area,[30] where he socialized with Russian émigrés—notably George de Mohrenschildt.[31][32] In March 1963, a bullet narrowly missed General Edwin Walker at his Dallas residence; a witness observed two conspicuous men. Relying on Marina's testimony, a note left by Oswald, and ballistic evidence, the Warren Commission attributed this assassination attempt to Oswald.[33]

In April 1963, Oswald returned to his birthplace, New Orleans,[34] and established an independent chapter of the pro-Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee, of which he was the sole member.[35][36] While passing out pro-Castro literature alongside unknown compatriots, Oswald was arrested after scuffling with anti-Castro Cuban exiles.[37][38][note 3] In late September 1963, Oswald traveled to Mexico City, where, according to the Warren Commission, he visited the Soviet and Cuban embassies.[40] On October 3, Oswald returned to Dallas and found work at the Texas School Book Depository on Dealey Plaza.[41] During the workweek he lived separately from Marina at a Dallas rooming house.[42] On the morning of the assassination, he carried a long package (which he told coworkers contained curtain rods) into the Depository;[43][note 4] the Warren Commission concluded that this package contained Oswald's disassembled rifle.[46]

November 22

Kennedy's arrival in Dallas and route to Dealey Plaza

On November 22, Air Force One arrived at Dallas Love Field at 11:40 a.m.[47] President Kennedy and the First Lady boarded a 1961 Lincoln Continental convertible limousine to travel to a luncheon at the Dallas Trade Mart.[48][13] Other occupants of this vehicle—the second in the motorcade—were Secret Service Agent Bill Greer, who drove; Special Agent Roy Kellerman in the front passenger seat; and Governor Connally and his wife Nellie, who sat just forward of the Kennedys.[49][50] Four Dallas police motorcycle officers accompanied the Kennedy limousine.[51] Vice President Johnson, his wife Lady Bird, and Senator Yarborough rode in another convertible.[52]

The motorcade's meandering 10-mile (16 km) route through Dallas was designed to give Kennedy maximum exposure to crowds by passing through a suburban section of Dallas,[48][13] and Main Street in Downtown Dallas, before turning right on Houston Street. After another block, the motorcade was to turn left onto Elm Street, pass through Dealey Plaza, and travel a short segment of the Stemmons Freeway to the Trade Mart.[13] The planned route had been reported in newspapers several days in advance.[13] Despite concerns about hostile protestors—Kennedy's UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson had been spat on in Dallas a month earlier—Kennedy was greeted warmly by enthusiastic crowds.[53][54][55]

Shooting

Kennedy's limousine entered Dealey Plaza at 12:30 p.m. CST.[3] Nellie Connally turned and commented to Kennedy, who was sitting behind her, "Mr. President, they can't make you believe now that there are not some in Dallas who love and appreciate you, can they?" Kennedy's reply – "No, they sure can't" – were his last words.[56]

From Houston Street, the limousine made the planned left turn onto Elm, passing the Texas School Book Depository.[57] As it continued down Elm Street, multiple shots were fired: about 80% of the witnesses recalled hearing three shots.[58] The Warren Commission concluded that three shots were fired and noted that most witnesses recalled that the second and third shots were bunched together.[59] Shortly after Kennedy began waving, some witnesses heard the first gunshot, but few in the crowd or motorcade reacted, many interpreting the sound as a firecracker or backfire.[60][61][note 5]

Within one second of each other, Governor Connally and Mrs. Kennedy turned abruptly from their left to their right.[64] Connally—an experienced hunter—immediately recognized the sound as that of a rifle and turned his head and torso rightward, noting nothing unusual behind him.[62] He testified that he could not see Kennedy, so he started to turn forward again (turning from his right to his left), and that when his head was facing about 20 degrees left of center,[65] he was struck in his upper right back by a shot he did not hear,[65][66] then shouted, "My God. They're going to kill us all!"[67]

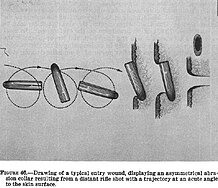

According to the Warren Commission and the HSCA, Kennedy was waving to the crowds on his right when a shot entered his upper back and exited his throat just beneath his larynx.[68][69] He raised his elbows and clenched his fists in front of his face and neck, then leaned forward and leftward. Mrs. Kennedy, facing him, put her arms around him.[65][70][71] Although a serious wound, it likely would have been survivable.[72]

According to the Warren Commission's single-bullet theory—derided as the "magic bullet theory" by conspiracy theorists—Governor Connally was injured by the same bullet that exited Kennedy's neck. The bullet created an oval-shaped entry wound near Connally's shoulder, struck and destroyed several inches of his right fifth rib, and exited his chest just below his right nipple, puncturing and collapsing his lung. That same bullet then entered his arm just above his right wrist and shattered his right radius bone. The bullet exited just below the wrist at the inner side of his right palm and finally lodged in his left thigh.[73][74][72]

As the limousine passed the grassy knoll,[75] Kennedy was struck a second time, by a fatal shot to the head.[76] The Warren Commission made no finding as to whether this was the second or third bullet fired, and concluded—as did the HSCA—that the second shot to strike Kennedy entered the rear of his head. It then passed in fragments through his skull, creating a large, "roughly ovular" [sic] hole on the rear, right side of the head, and spraying blood and fragments. His brain and blood spatter landed as far as the following Secret Service car and the motorcycle officers.[77][78][79][note 6]

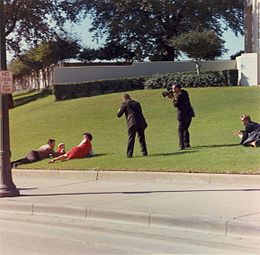

Secret Service Agent Clint Hill was riding on the running board of the car immediately behind Kennedy's limousine.[81] Hill testified to the Warren Commission that he heard one shot, jumped onto the street, and ran forward to board the limousine and protect Kennedy. Hill stated that he heard the fatal headshot as he reached the Lincoln, "approximately five seconds" after the first shot that he heard.[82] After the headshot, Mrs. Kennedy began climbing onto the limousine's trunk, but she later had no recollection of doing so.[83] Hill believed she may have been reaching for a piece of Kennedy's skull.[82] He jumped onto the limousine's bumper, and he clung to the car as it exited Dealey Plaza and sped to Parkland Memorial Hospital. After Mrs. Kennedy crawled back into her seat, both Governor and Mrs. Connally heard her repeatedly saying: "They have killed my husband. I have his brains in my hand."[65][84][85]

Bystander James Tague received a minor wound to the cheek—either from bullet or concrete curb fragments—while standing by the triple underpass.[86] Nine months later, the FBI removed the curb, and spectrographic analysis revealed metallic residue consistent with the lead core in Oswald's ammunition.[87] Tague testified before the Warren Commission and initially stated that he was wounded by either the second or third shot of the three shots that he remembered hearing. When the commission counsel pressed him to be more specific, Tague testified that he was wounded by the second shot.[88]

Aftermath in Dealey Plaza

As the motorcade left Dealey Plaza, some witnesses sought cover,[90] and others joined police officers to run up the grassy knoll in search of a shooter.[75][91] No shooter was found behind the knoll's picket fence.[92] Among the 178 witnesses who testified to the Warren Commission, 78 were unsure of the shots' origin, 49 believed they came from the Depository, and 21 thought they came from the grassy knoll.[93] No witness ever reported seeing anyone—with or without a gun—immediately behind the knoll's picket fence at the time of the shooting.[92]

Lee Bowers was in a two-story railroad switch tower 120 yards (110 m) behind the grassy knoll's picket fence; he was watching the motorcade and had an unobstructed view of the only route by which a shooter could flee the grassy knoll; he saw no one leaving the scene.[92] Bowers testified to the Warren Commission that "one or two" men were between him and the fence during the assassination: one was a familiar parking lot attendant and the other wore a uniform like a county courthouse custodian. He testified seeing "some commotion" on the grassy knoll at the time of the assassination: "something out of the ordinary, a sort of milling around, but something occurred in this particular spot which was out of the ordinary, which attracted my eye for some reason which I could not identify".[94][note 8]

At 12:36 p.m., teenager Amos Euins approached Dallas police Sergeant D.V. Harkness to report having seen a "colored man ... leaning out of the window [with] a rifle" on the sixth floor of the Depository during the assassination; in response, Harkness radioed that he was sealing off the Depository.[96] Witness Howard Brennan then approached a police inspector to report seeing a shooter—a white man in khaki clothing—in the same window.[97][98] Police broadcast Brennan's description of the man at 12:45 p.m.[99] Brennan testified that, after the second shot, "This man ... was aiming for his last shot ... and maybe paused for another second as though to assure himself that he had hit his mark."[100] Witness James R. Worrell Jr. also reported seeing a gun barrel emerge from a sixth floor Depository window.[101] Bonnie Ray Williams, who was on the fifth floor of the Depository, stated that the rifle's report was so loud and near that ceiling plaster fell onto his head.[102]

Oswald's flight, killing of J. D. Tippit, and arrest

When searching the sixth floor of the Depository, two deputies found an Italian Carcano M91/38 bolt-action rifle.[103][note 9] Oswald had purchased the used rifle the previous March under the alias "A. Hidell" and had it delivered to his Dallas P.O. box.[105] The FBI found Oswald's partial palm print on the barrel,[106][107][note 10] and fibers on the rifle were consistent with those of Oswald's shirt.[110] A bullet found on Governor Connally's hospital gurney and two fragments found in the limousine were ballistically matched to the Carcano.[111]

Oswald left the Depository and traveled by bus to his boarding house, where he retrieved a jacket and revolver.[112] At 1:12 p.m., police officer J. D. Tippit spotted Oswald walking in the residential neighborhood of Oak Cliff and called him to his patrol car. After an exchange of words, Tippit exited his vehicle; Oswald then shot Tippit three times in the chest. As Tippit lay on the ground, Oswald fired a final shot into Tippit's right temple. Oswald then calmly walked away before running as witnesses emerged.[113]

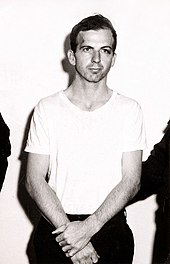

| Oswald speaking in custody | |

|---|---|

As Dallas police officers conducted a roll call of Depository employees, Oswald's supervisor Roy Truly realized that Oswald was absent and notified the police.[114] Based on a false identification of Oswald, Dallas police raided a library in Oak Cliff before realizing their mistake.[115] At 1:36 p.m., the police were called after a conspicuous Oswald, tired from running, was seen sneaking into the Texas Theatre without paying.[116] With the film War Is Hell still playing, Dallas policemen arrested Oswald after a brief struggle in which Oswald drew his fully loaded gun.[117] He denied shooting anyone and claimed he was being made a "patsy" because he had lived in the Soviet Union.[118]

Kennedy declared dead; Johnson sworn in

At 12:38 p.m., Kennedy arrived in the emergency room of Parkland Memorial Hospital.[119] Although Kennedy was still breathing after the shooting, his personal physician, George Burkley, immediately saw that survival was impossible.[120][121][122] After Parkland surgeons performed futile cardiac massage, Kennedy was pronounced dead at 1:00 p.m., 30 minutes after the shooting.[121] CBS host Walter Cronkite broke the news on live television.[123][124]

The Secret Service was concerned about the possibility of a larger plot and urged Johnson to leave Dallas and return to the White House, but Johnson refused to do so without any proof of Kennedy's death.[125][note 11] Johnson returned to Air Force One around 1:30 p.m., and shortly thereafter, he received telephone calls from advisors McGeorge Bundy and Walter Jenkins advising him to depart for Washington, D.C., immediately.[127] He replied that he would not leave Dallas without Jacqueline Kennedy and that she would not leave without Kennedy's body.[125][127] According to Esquire, Johnson did "not want to be remembered as an abandoner of beautiful widows".[127]

At the time of Kennedy's assassination, the murder of a president was not under federal jurisdiction.[128] Accordingly, Dallas County medical examiner Earl Rose insisted that Texas law required him to perform an autopsy.[129][130] A heated exchange between Kennedy's aides and Dallas officials nearly erupted into a fistfight before the Texans yielded and allowed Kennedy's body to be transported to Air Force One.[129][130][131] At 2:38 p.m., with Jacqueline Kennedy at his side, Johnson was administered the oath of office by federal judge Sarah Tilghman Hughes aboard Air Force One, shortly before departing for Washington with Kennedy's coffin.[132]

Immediate aftermath

Autopsy

Where bungled autopsies are concerned, President Kennedy's is the exemplar.

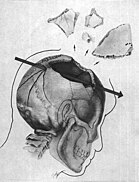

President Kennedy's autopsy was performed at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland on the night of November 22. Jacqueline Kennedy had selected a naval hospital as the postmortem site as President Kennedy had been a naval officer during World War II.[134][135] The autopsy was conducted by three physicians: naval commanders James Humes and J. Thornton Boswell, with assistance from ballistics wound expert Pierre A. Finck; Humes led the procedure.[136] Under pressure from the Kennedy family and White House staffers to expedite the procedure, the physicians conducted a "rushed" and incomplete autopsy.[137] Kennedy's personal physician, Rear Admiral George Burkley,[138] signed a death certificate on November 23 and recorded that the cause of death was a gunshot wound to the skull.[139][140]

Three years after the autopsy, Kennedy's brain—which had been removed and preserved for later analysis—was found to be missing when the Kennedy family transferred material to the National Archives.[141][142] Conspiracy theorists often claim that the brain may have shown that the headshot entered from the front. Alternatively, the HSCA concluded that an assistant to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the president's brother, likely removed the footlocker holding the brain and other materials at his direction, and he "either destroyed these materials or otherwise rendered them inaccessible" to prevent "misuse" of said material or to hide the extent of the president's chronic illnesses and consequent medication.[143][142] Some autopsy X-rays and photographs have also been lost.[144]

Most historians regard the autopsy as the "most botched" segment of the government's investigation.[133] The HSCA forensic pathology panel concluded that the autopsy had "extensive failings", including failure to take sufficient photographs, failure to determine the exact exit or entry point of the head bullet, not dissecting the back and neck, and neglecting to determine the angles of gunshot injuries relative to body axis.[145] The panel further concluded that the two doctors were not qualified to have conducted a forensic autopsy. Panel member Milton Helpern—Chief Medical Examiner for New York City—said that selecting Humes (who had only taken a single course on forensic pathology) to lead the autopsy was "like sending a seven-year-old boy who has taken three lessons on the violin over to the New York Philharmonic and expecting him to perform a Tchaikovsky symphony".[146]

Funeral

Following the autopsy, Kennedy lay in repose in the East Room of the White House for 24 hours.[147][148] President Johnson issued Presidential Proclamation 3561, declaring November 25 to be a national day of mourning,[149][150] and that only essential emergency workers be at their posts.[151] The coffin was then carried on a horse-drawn caisson to the Capitol to lie in state. Hundreds of thousands of mourners lined up to view the guarded casket,[152][153] with a quarter million passing through the rotunda during the 18 hours of lying in state.[152] Even in the Soviet Union—according to a memo by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover—news of the assassination "was greeted by great shock and consternation and church bells were tolled in the memory of President Kennedy".[154][155]

Kennedy's funeral service was held on November 25, at St. Matthew's Cathedral,[156] with the Requiem Mass led by Cardinal Richard Cushing.[156] About 1,200 guests, including representatives from over 90 countries, attended.[157][158] Although there was no formal eulogy,[159][160] Auxiliary Bishop Philip M. Hannan read excerpts from Kennedy's speeches and writings.[158] After the service, Kennedy was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.[161] An eternal flame was lit at his burial site in 1967.[162]

Killing of Oswald

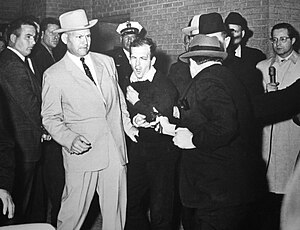

On Sunday, November 24, at 11:21 a.m., as Oswald was being escorted to a car in the basement of Dallas Police headquarters for the transfer from the city jail to the county jail, he was shot by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby. The shooting was broadcast live on television.[42] Robert H. Jackson of the Dallas Times Herald photographed the shooting which was titled, Jack Ruby Shoots Lee Harvey Oswald for which he was awarded the 1964 Pulitzer Prize for Photography.[163]

Drifting in and out of consciousness, Oswald was taken by ambulance to Parkland Memorial Hospital; he was treated by the same surgeons who had tried to save Kennedy.[164] The bullet had entered his lower left chest but had not exited; major heart blood vessels such as the aorta and inferior vena cava were severed, and the spleen, kidney, and liver were hit.[165] Despite surgical intervention and defibrillation, Oswald died at 1:07 p.m.[166]

Arrested immediately after the shooting, Ruby testified to the Warren Commission that he had been distraught by Kennedy's death and that killing Oswald would spare "Mrs. Kennedy the discomfiture of coming back to trial". He also stated he shot Oswald on the spur of the moment when the opportunity presented itself, without considering any reason for doing so.[167] Initially, Ruby wished to represent himself in his trial until his lawyer Melvin Belli dissuaded him: Belli argued that Ruby had an episode of psychomotor epilepsy and was thus not responsible.[168] Ruby was convicted, but the decision was overturned on appeal. While awaiting retrial in 1967,[169] Ruby died of a pulmonary embolism, secondary to cancer. Like Oswald and Kennedy, Ruby was declared dead at Parkland Hospital.[170]

Films and photographs of the assassination

My god, I saw the whole thing. I saw the man's brains come out of his head.

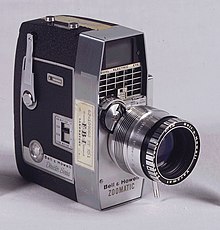

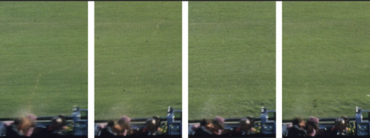

Standing on the pergola wall some 65 feet (20 m) from the road,[171] tailor Abraham Zapruder recorded Kennedy's killing on 26 seconds of silent 8 mm film — known as the Zapruder film.[172] Frame 313 captures the exact moment at which Kennedy's head explodes.[173] Life magazine published frame enlargements from the Zapruder film shortly after the assassination.[172][174] The footage itself was first publicly shown at the 1969 trial of Clay Shaw, and on television in 1975 by Geraldo Rivera.[175] In 1999, an arbitration panel ordered the federal government to pay $615,384 per second of film to Zapruder's heirs, valuing the complete film at $16 million (equivalent to $27.5 million in 2022).[176][177]

Zapruder was one of at least 32 people in Dealey Plaza known to have made film or still photographs at or around the time of the shooting.[178] Most notably among the photographers, Mary Moorman took several photos of Kennedy with her Polaroid, including one of Kennedy less than one-sixth of a second after the headshot.[179]

As well as Zapruder, Charles Bronson, Marie Muchmore, and Orville Nix filmed the assassination, but at farther distances than Zapruder.[180][181] Of the three, only Nix — who filmed the assassination from the opposite side of Elm Street from Zapruder, capturing the grassy knoll — actually recorded the fatal shot.[181][182][note 12] In 1966, Nix claimed that, after he gave the film to the FBI, the duplicate that they returned had frames "missing" or "ruined". Although lower-quality duplicates exist, the original film has been missing since 1978.[182] Previously unknown footage filmed by George Jefferies was released in 2007.[183][184] Recorded a few blocks before the shooting, the film captures Kennedy's bunched suit jacket, explaining the discrepancies between the location of the bullet hole in Kennedy's back and his jacket.[185]

Some films and photographs captured an unidentified woman apparently filming the assassination; researchers have nicknamed her the Babushka Lady due to the shawl around her head.[186] In 1978, Gordon Arnold came forward and claimed that he had filmed the assassination from the grassy knoll and that a police officer had confiscated his film.[187] Arnold is not visible in any photographs taken of the area, which Vincent Bugliosi—author of Reclaiming History—called "conclusive photographic proof that Arnold's story was fabricated".[188]

Official investigations

Dallas Police

At the Dallas Police headquarters, officers interrogated Oswald about the shootings of Kennedy and Tippit; these intermittent interviews lasted for approximately 12 hours between 2:30 p.m. on November 22 and 11 a.m. on November 24.[189] Throughout, Oswald denied any involvement and resorted to statements that were found to be false.[190]

Captain J. W. Fritz of the Homicide and Robbery Bureau did most of the questioning and kept only rudimentary notes.[191][192] Days later, Fritz wrote a report of the interrogation from notes he made afterwards.[191] There were no stenographic or tape recordings. Representatives of other law enforcement agencies were also present, including the FBI and the Secret Service, and occasionally participated in the questioning.[190] Several of the FBI agents who were present wrote contemporaneous reports of the interrogation.[193]

On the evening of November 22, Dallas Police performed paraffin tests on Oswald's hands and right cheek in an effort to establish whether or not he had recently fired a weapon. The results were positive for the hands and negative for the right cheek. Such tests were unreliable,[190][194] and the Warren Commission did not rely on these results.[190]

The Dallas police forced Oswald to host a press conference after midnight on November 23, and, early in the investigation, made many leaks to the media. Their conduct angered Johnson, who instructed the FBI to tell them to "stop talking about the assassination".[128] Dallas Police, after the FBI expressed concerns that someone might try to kill Oswald, assured federal authorities that they would provide him adequate protection.[195]

FBI investigation

The FBI immediately launched an investigation into the assassination, relying on a federal statute that forbade assaulting a federal officer. Within 24 hours of the killing, FBI Director Hoover sent President Johnson a preliminary report finding that Oswald was the sole culprit. After Ruby killed Oswald, Johnson decided that the Texan authorities were incompetent and instructed the FBI to conduct a complete investigation.[128]

On December 9, 1963, the Warren Commission received the FBI's report of its investigation which concluded that three bullets had been fired—the first striking Kennedy in the upper back; the second striking Connally; and the third striking Kennedy in the head, killing him.[197] The FBI continued to serve as the main investigative arm of the Warren Commission in the field. A total of 169 FBI agents worked on the case, conducting over 25,000 interviews and writing over 2,300 reports.[196]

The thoroughness of the FBI's investigation is contested. Bugliosi applauded its quality and cites conspiracy theorist Harrison Edward Livingstone's praise of the FBI's commitment to following all leads.[198] In its 1979 report, the HSCA found that the FBI's investigation of pro- and anti-Castro Cubans, and any connections to Oswald or Ruby, was insufficient.[196] The HSCA also noted that Hoover "seemed determined [to make the case that Oswald was the lone assassin] within 24 hours of the assassination".[199]

Warren Commission

On November 29, President Johnson established by executive order "The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy" and selected Chief Justice Earl Warren of the U.S. Supreme Court to chair the investigation, commonly known as the Warren Commission.[200][128] Its 888-page final report was presented to Johnson on September 24, 1964, and made public three days later.[201] It concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone in killing Kennedy and wounding Connally, and that Jack Ruby acted alone in killing Oswald.[202][203] It made no conclusions as to Oswald's motive, but noted his Marxism, anti-authoritarianism, violent tendencies, failure to form personal relationships, and his desire to be significant in history.[204]

Upon examining the Zapruder film, commission staffers realized that the FBI's gunshot theory was impossible. The reaction times of Kennedy and Connally were too close to have been caused by two bullets from Oswald: the reaction interval was less than the 2.3 seconds that it took to reload.[205][206] This was one of the commission's most crucial findings: that a single shot caused the non-fatal wounds of Kennedy and Connally, known as the "single-bullet theory".[207][208] In May 1964, staffer Arlen Specter replicated the single bullet's trajectory via a reenactment in Dealey Plaza: the bullet's path was exactly consistent with Kennedy's and Connally's wounds.[209]

Out of the eight commission members, three—Representative Hale Boggs and Senators John Cooper and Richard Russell—found the theory "improbable"; their qualms were not mentioned in the final report.[210] Conspiracy theorists labelled this theory the "magic bullet theory", partly due to the bullet's intact and purportedly pristine state. However, the HSCA's Michael Baden noted that the bullet, despite its lack of fragmentation, was fundamentally deformed.[73] In 2023, Secret Service Agent Paul Landis—who had stood on the running board of Kennedy's car—told The New York Times that he retrieved the "magic bullet" from immediately behind Kennedy's seat upon arrival at Parkland, and that he placed it on Kennedy's stretcher. Landis believes that the bullet dislodged from a shallow wound in Kennedy's back.[211]

As well as the Warren Report's 27 published volumes, the commission created hundreds of thousands of pages of investigative reports and documents. Relman Morin stated that "Never in history was a crime probed as intensely"; Bugliosi concluded that the commission's basic findings have "held up remarkably well".[212] According to Gerald Posner, the Warren report is "universally derided" by the American public.[213] Walter Cronkite noted that, "Although the Warren Commission had full power to conduct its own independent investigation, it permitted the FBI and the CIA to investigate themselves – and so cast a permanent shadow on the answers."[214] According to a 2014 report by CIA Chief Historian David Robarge, then-CIA director John A. McCone was involved in a "benign cover-up" by withholding information from the commission.[215]

Trial of Clay Shaw

On March 22, 1967, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison arrested and charged New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw with conspiring to assassinate President Kennedy, with the help of Oswald, David Ferrie, and others.[216] A respected businessman who had helped renovate and preserve the French Quarter,[216] Shaw was described as "the unlikeliest villain since Oscar Wilde".[217] Both Shaw and the neurotic, avidly anti-Castro Ferrie were members of New Orleans' gay community.[218] Ferrie died, possibly by suicide, four days after news of the investigation broke.[219] On The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in 1968, Garrison first publicly alleged that Shaw and Ferrie had been part of a larger CIA scheme to kill Kennedy and frame Oswald.[220] In the 34-day trial conducted in 1969,[221] Garrison played the Zapruder film and argued that the backwards motion of Kennedy's head after the fatal shot was indicative of a shooter in front on the grassy knoll.[222]

After a brief deliberation, the jury found Shaw not guilty.[221] Mark Lane interviewed the jurors after the trial and stated that some believed that Shaw likely was involved in a conspiracy but that there was insufficient evidence to convict.[223][224] Lane's claims have been disputed by playwright James Kirkwood—a personal friend of Clay Shaw—who said that he met several jurors who denied ever speaking to Lane.[225][226] Kirkwood also questioned Lane's claim that the jury believed that there was a conspiracy:[227] jury foreman Sidney Hebert told Kirkwood, "I didn't think too much of the Warren Report either until the trial. Now I think a lot more of it than I did before."[228]

According to academic E. Jerald Ogg, the Shaw trial is now widely regarded as a "travesty of justice";[229] Kirkwood likened the trial to a Spanish Inquisition hearing.[230] Other observers have characterized the proceedings as relying on homophobia.[231] It remains the only trial to be brought for the Kennedy assassination.[216] In 1979, former CIA director Richard Helms testified that Shaw had been a part-time contact of the Domestic Contact Service of the CIA, through which Shaw volunteered information from his travels abroad, mostly to Latin America. However, according to Max Holland, some 150,000 Americans were contacts.[232] In 1993, the PBS program Frontline obtained a group photograph that featured Ferrie and Oswald together at a 1955 cookout for the Civil Air Patrol: Ferrie had denied ever knowing Oswald.[233]

Ramsey Clark Panel

Excluding Chief Justice Warren, the members of Warren Commission did not view the photographs or X-rays taken during Kennedy's autopsy. According to Warren, this was to avoid having to publicly release the explicit material to "sensation mongers".[234] Due to persistent speculation, in February 1968, Attorney General Ramsey Clark convened a panel of four medical experts to examine the photographs and X-rays from the Kennedy autopsy. Their findings concurred with the Warren Commission: Kennedy was struck by two bullets, both from behind.[235]

Rockefeller Commission

In 1975, President Gerald Ford—who had been a member of the Warren Commission a decade prior—established the United States President's Commission on CIA Activities within the United States, better known as the Rockefeller Commission after its chairman, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller.[236][237] The commission received a mandate to determine if any domestic activities by the CIA were unlawful and to make appropriate recommendations: accordingly, it also re-examined the Kennedy assassination.[235]

After five months of investigation, the Rockefeller Commission submitted its report to President Ford.[238] The report reviewed the medical evidence and agreed that Kennedy had been killed by two shots from behind.[235] Refuting Garrison's claims that the backwards motion of Kennedy's head seen on the Zapruder film was indicative of a grassy knoll shooter,[222] the commission found that "such a motion would be caused by a violent straightening and stiffening of the entire body as a result of a seizure-like neuromuscular reaction to major damage inflicted to nerve centers in the brain".[239] The later HSCA suggested that the "propulsive effect resulting from brain matter" ejected from the exit wound may have been responsible.[240] Pathologist Vincent Di Maio testified before the HSCA that the notion of a "transfer of momentum" from a grassy knoll bullet was unfounded and something from "Arnold Schwarzenegger pictures".[239]

The Rockefeller Commission also sought to determine whether CIA operatives—particularly E. Howard Hunt and Frank Sturgis—were present in Dealey Plaza during the assassination, and whether they were among the "three tramps" pictured shortly after the assassination. The commission found no evidence for these claims.[237] It also inquired into purported connections between the CIA and Oswald and Ruby, for which it found no evidence and concluded was "farfetched speculation".[237] They concluded that there was "no credible evidence of CIA involvement".[235]

Church Committee

In 1975, following the Watergate scandal and the revelation of CIA misconduct by Seymour Hersh (the CIA's so-called "Family Jewels"), the U.S. Senate launched the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities—better known as the Church Committee after its chairman, Senator Frank Church.[241][242][243] The committee was to investigate all improper and unlawful actions by the CIA and FBI, both foreign and domestic. Due to persisting theories, the Church Committee organized a subcommittee (staffed by Senators Richard Schweiker and Gary Hart) to examine CIA and FBI conduct pertaining to the assassination.[244]

In its final report, the Church Committee concluded that there was no evidence of a CIA- or FBI-led conspiracy.[244] They found that the original investigation into the assassination was "deficient" and criticized the FBI and CIA for withholding information from the Warren Commission. In particular, it noted that knowledge of the CIA's many failed attempts to assassinate Castro may have significantly affected the course of the investigation.[244][245] Moreover, the Church Committee revealed that the CIA had conspired with the Mafia in these plots against Castro.[244][246] These revelations led to further public scrutiny of the assassination.[245]

United States House Select Committee on Assassinations

As a result of increasing public and congressional skepticism of the Warren Commission's findings and the transparency of government agencies,[245] in 1976 the House Select Committee on Assassinations was created to investigate the assassinations of Kennedy and that of Martin Luther King, Jr.[248]

The HSCA conducted its inquiry until 1978 and issued its final report the following year, concluding that Kennedy was likely assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.[249] They concluded that there was a "high probability" that a fourth shot was fired from the grassy knoll, but they stated that this shot missed Kennedy.[250] Concerning the conclusions of "probable conspiracy", four of the twelve committee members wrote dissenting opinions.[251]

The HSCA also concluded that previous investigations into Oswald's responsibility were "thorough and reliable" but did not adequately investigate the possibility of a conspiracy, and that federal agencies performed with "varying degrees of competency".[252] Specifically, the FBI and CIA were found to be deficient in sharing information with other agencies and the Warren Commission. Instead of furnishing all relevant information, the FBI and CIA only responded to specific requests and were still occasionally inadequate.[253] Furthermore, the Secret Service did not properly analyze information it possessed prior to the assassination and was inadequately prepared to protect Kennedy.[251]

The chief reason for the conclusion of "probable conspiracy" was, according to the report's dissent, the subsequently discredited acoustic analysis of a police channel Dictabelt recording.[250][254][255] In accordance with the recommendations of the HSCA, the Dictabelt recording and acoustic evidence of a second assassin was subsequently reexamined. In light of investigative reports from the FBI's Technical Services Division and a specially appointed National Academy of Sciences Committee determining that "reliable acoustic data do not support a conclusion that there was a second gunman",[254] the Justice Department concluded "that no persuasive evidence can be identified to support the theory of a conspiracy" in the Kennedy assassination.[255]

JFK Act and Assassination Records Review Board

In 1991, Oliver Stone's film JFK renewed interest in the assassination and particularly in the still-classified files relating to the killing. In response, Congress passed the JFK Records Act, which called for the National Archives to collect and release all assassination-related documents within 25 years.[256][257][258] The act also mandated the creation of an independent office, the Assassination Records Review Board, to review the submitted records for completeness and continued secrecy. From 1994 until 1998, the Assassination Records Review Board gathered and unsealed about 60,000 documents comprising over 4 million pages.[259][260]

A 1998 staff report for the Assassinations Records Review Board contended that brain photographs in the Kennedy records may not be of Kennedy's brain, reportedly showing much less damage than Kennedy sustained. Dr. Boswell refuted these allegations.[261] The board also found that, conflicting with the photographic images showing no such defect, several witnesses (at both Parkland hospital and the autopsy) remembered a large wound in the back of Kennedy's head.[262] The board, and board member Jeremy Gunn, stressed the problems with witness testimony, urging people to weigh all of the evidence, with due concern for human error, rather than take single statements as "proof" for one theory or another.[263]

All remaining assassination-related records were scheduled to be released by October 2017, with the exception of documents certified for continued postponement by succeeding presidents due to "identifiable harm... to the military, defense, intelligence operations, law enforcement, or conduct of foreign relations... of such gravity that it outweighs the public interest in disclosure."[264][265] President Donald Trump said in October 2017 that he would not block the release of documents,[265] but in April 2018—the deadline he set to release all JFK records—Trump blocked the release of some records until October 2021.[266][257] President Joe Biden, citing the COVID-19 pandemic, delayed the release further,[267][268] before releasing 13,173 unredacted documents in 2022.[269] A second group of files were unsealed in June 2023, at which point 99 percent of documents had been made public.[269][270]

Conspiracy theories

The Kennedy assassination has been described as "the mother of all conspiracies".[271] For decades, polls have consistently found that a majority of Americans believe there was a conspiracy;[272][273][274] some 1,000 to 2,000 books—mostly pro-conspiracy—have been written about the killing.[275] Across different theories, Oswald's role varies from co-conspirator to entirely innocent.[276][277] Common culprits include the FBI, the CIA, the U.S. military,[277] the Mafia,[278] the military-industrial complex,[278] Vice President Johnson, Castro, the KGB, or some combination thereof.[279] Bugliosi estimated that a total of 42 groups, 82 assassins, and 214 people had been accused in various assassination theories.[280]

Conspiracy theorists often argue that there were multiple shooters—a "triangulation of crossfire"—and that the fatal shot was fired from the grassy knoll and struck Kennedy in the front of the head.[281] Individuals present in Dealey Plaza have been the subject of much speculation, including the three tramps, the umbrella man, and the purported Badge Man.[282][283][284] Conspiracy theorists argue that the autopsy and official investigations were flawed or, at worst, complicit,[285] and that witnesses to the Kennedy assassination met mysterious and suspicious deaths.[286]

Conspiracy theories have been espoused by notable figures, such as L. Fletcher Prouty, Chief of Special Operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Kennedy, who believed that elements of the U.S. military and intelligence communities had conspired to assassinate the president.[287] Governor Connally also rejected the single-bullet theory,[288][289] and President Johnson reportedly expressed doubt regarding the Warren Commission's conclusions prior to his death.[290] According to Robert F. Kennedy Jr., his father believed that the Warren Report was a "shoddy piece of craftsmanship" and that John F. Kennedy had been killed by a conspiracy, possibly involving Cuban exiles and the CIA.[291] Communist rulers like Castro and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev believed that Kennedy had been killed by right-wing Americans.[292] Former CIA director R. James Woolsey has argued that Oswald killed Kennedy as part of a Soviet conspiracy.[293]

Legacy

Political impact and memorialization

On November 27—five days after the assassination—President Johnson delivered his "Let Us Continue" speech to Congress.[295] Effectively an inaugural address,[296] Johnson called for the realization of Kennedy's policies, particularly on civil rights; this effort soon materialized as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[297] Confusion surrounding Johnson's succession led to the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the U.S Constitution, which was adopted in 1967 and affirmed that the vice president became president upon the president's death.[298]

On November 29, President Johnson issued Executive Order 11129, renaming Florida's Cape Canaveral—a name borne since at least 1530—to Cape Kennedy.[299][note 13] NASA's Launch Operations Center, located on the cape, was also renamed as the Kennedy Space Center.[301] The federal government honored Kennedy in other ways, such as replacing the Benjamin Franklin half dollar with the Kennedy half dollar,[294] and renaming Washington, D.C.'s long-planned National Culture Center as the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[302] New York City's airport was also renamed as the John F. Kennedy International Airport.[303]

Kennedy's assassination also resulted in an overhaul of the Secret Service and its procedures. Open limousines were eliminated, staffing was significantly increased, and specialized teams like counter-sniper units were established. The agency's budget has also increased, from $5.5 million in 1963 (equivalent to $42 million in 2013) to over $1.6 billion by the 50th anniversary in 2013.[304]

Cultural impact and depictions

- They say they can't believe it; It's a sacrilegious shame.

- Now, who would want to hurt such a hero of the game?

- But you know I predicted it; I knew he had to fall.

- How did it happen? Hope his suffering was small.

- Tell me every detail, for I've got to know it all,

- And do you have a picture of the pain?

John F. Kennedy's assassination was the first of four major assassinations during the 1960s, coming two years before the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, and five years before the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968.[306] For the public, Kennedy's assassination mythologized him into a heroic figure.[307] Although scholars typically regard Kennedy as a good but not great president,[308] public opinion polls consistently find him the most popular post-WWII president.[308][309]

Kennedy's murder left a lasting impression on many worldwide. As with the attack on Pearl Harbor of December 7, 1941, and, much later, the September 11 attacks in 2001, asking "Where were you when you heard about President Kennedy's assassination?" became a common topic of discussion.[310][311][312][313][314] Journalist Dan Rather opined that the Kennedy assassination will be discussed "a hundred years from now, a thousand years from now, in somewhat the same way as people discuss the Iliad. Different people read Homer's description of the war and come to different conclusions, and so it shall be for Kennedy's death."[315]

Along with Oliver Stone's JFK, the assassination has been portrayed in several films: the pro-conspiracy, Dalton Trumbo–written Executive Action (1973) was the first feature film to depict the assassination.[316] Besides explicit portrayals, some critics have argued that the Zapruder film—which itself has been featured in many films and television episodes—advanced cinéma vérité or inspired more graphic depictions of violence in American cinema.[173][317][318][319] Many works of literature have also explored the killing, such as Don DeLillo's 1988 novel Libra in which Oswald is a CIA agent,[320] James Ellroy's 1995 work American Tabloid,[321] and Stephen King's 2011 time travel novel 11/22/63.[322] The assassination has also been featured in several musical compositions, such as Igor Stravinsky's 1964 piece Elegy for J.F.K. and Phil Ochs' 1966 song "Crucifixion",[323][324] which reportedly brought Robert Kennedy to tears.[324][325] Other songs include "Abraham, Martin and John" (1968) and Bob Dylan's "Murder Most Foul" (2020).[326][327]

Artifacts, museums, and locations today

In 1993, the National Park Service designated Dealey Plaza, the surrounding buildings, the overpass, and a portion of the adjacent railyard as a National Historic Landmark District.[328] The Depository and its Sixth Floor Museum, operated by the city of Dallas, draw over 325,000 visitors annually.[329]

The Boeing 707 that served as Air Force One at the time of the assassination is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force; Kennedy's limousine is at the Henry Ford Museum.[330] The Lincoln Catafalque, on which Kennedy's coffin rested in the Capitol, is exhibited at the Capitol Visitor Center.[331] Jacqueline's pink suit, autopsy X-rays, and President Kennedy's blood-stained clothing are in the National Archives, with access controlled by the Kennedy family. Other items in the Archives include Parkland Hospital trauma room equipment; Oswald's rifle, diary, and revolver; bullet fragments; and the limousine's windshield.[330] The Texas State Archives preserve Connally's bullet-punctured clothes; the gun Ruby used to kill Oswald came into the possession of Ruby's brother Earl, and was sold in 1991 for $220,000 (equivalent to $439,000 in 2022).[332]

At the direction of Robert F. Kennedy, some items were destroyed. The casket in which Kennedy's body was transported from Dallas to Washington was dropped into the sea, because "its public display would be extremely offensive and contrary to public policy".[333]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ This photo and a similar one are known as the "backyard photographs"; according to Bugliosi, it is one of the pieces of evidence most damning for Oswald. Oswald told Dallas police that the photographs were not genuine and that someone must have superimposed his head.[15] Marina Oswald testified that she took the pictures.[16]

- ^ In 1964, KGB Agent Yuri Nosenko defected to the United States. He divulged that Soviet intelligence surveilled Oswald, regarded him as mentally unstable, and had no association with him.[24] Although the FBI trusted Nosenko, the CIA believed that he was a mole and convinced the Warren Commission not to interview him.[25]

- ^ At Oswald's request, he met with FBI Special Agent John Quigley while in custody. Posner cites this as proof that Oswald was not a government agent, questioning why he might "blow his cover".[39]

- ^ Jack Dougherty, the only witness who saw Oswald enter the Depository on the morning of the assassination, testified to the Warren Commission that he did not remember seeing Oswald with any package.[44] Bugliosi questioned his reliability as a witness: Dougherty's father told FBI agents on November 23 that his son "had considerable difficulty in coordinating his mental facilities with his speech".[45]

- ^ After the first shot, witness Virgie Rachley—an employee at the Texas School Book Depository—reported seeing sparks on the pavement shortly behind the president's limousine.[62]

- ^ Student Billy Harper later found a fragment of Kennedy's skull on the road.[80]

- ^ The journalists pictured with them arrived as the end of the motorcade passed through Dealey Plaza.[89]

- ^ Bugliosi notes that Lee Bowers Jr. did not mention the "commotion" in an earlier affidavit, in which Bowers did take time to list all other suspicious happenings like circling vehicles with "Goldwater for '64" stickers. Moreover, conspiracy theorist Jim Moore questions whether Bowers could even have seen the area. Bowers testified that he "threw [the] red-on-red [signal]" just after the fatal shot, but the grassy knoll was partially obstructed from Bowers' position at the work panel.[95]

- ^ Three spent cartridges were found on the floor. One live round was found in the rifle. Dallas policemen thoroughly photographed the rifle before its removal.[104]

- ^ Lieutenant Day of the Dallas police examined the weapon prior to its seizure by the FBI. He found and photographed fingerprints on the trigger housing. Although Day believed the prints to be those of Oswald's right middle and ring fingers, the ridges were not clear enough to make a positive identification. Day then discovered a palm-print on the barrel underneath the wooden stock. He tentatively identified it as Oswald's, but was not able to photograph or analyze it in more depth as the FBI took the Carcano.[108] In D.C., FBI fingerprint expert Sebastian Latona found the photographs and extant prints to be "insufficient" as to make any conclusion. The rifle was returned to the Dallas police on November 24.[107] Five days later, the FBI made a positive identification using a card from Day.[109]

- ^ At the time of Kennedy's assassination, most of his cabinet was on a trip to Japan.[126]

- ^ Nix himself believed that the shots had come from the grassy knoll.[182]

- ^ In 1973, due to Floridians' discontent with the change, Florida Governor Reubin Askew mandated that Cape Kennedy be referred to as Cape Canaveral on all state documents and maps. The U.S. Board of Geographic Names accepted the name change later that year.[300]

Citations

- ^ "John F. Kennedy". The White House.

- ^ "John F. Kennedy: A Featured Biography". United States Senate.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (1998), p. xi.

- ^ "1960 Electoral College Results". National Archives.

- ^ "1960 The Cold War". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

- ^ Sabato (2013), pp. 422–423.

- ^ Hinckle & Turner (1981), pp. ix, 15, 18.

- ^ Jones (2008), pp. 41, 50, 94.

- ^ Borger (2022)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 13–16.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 17–23.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Warren (1964), p. 40.

- ^ White (1965), p. 3.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 792.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 793.

- ^ Pontchartrain (2019)

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 683.

- ^ a b Posner (1993), p. 28.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 17–19.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 32–33, 46.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 46–53.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 34–36.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 697.

- ^ Posner (1993), p. 53.

- ^ McMillan (1977), pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Warren (1964), p. 712.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 714.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 82–83, 85, 100.

- ^ Summers (2013), pp. 152–160.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 183.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 403.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 125–127.

- ^ Warren (1964), pp. 728–729.

- ^ Summers (2013), p. 211.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 151–152.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 153–155.

- ^ Posner (1993), pp. 172–190.

- ^ Warren (1964), pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Bagdikian (1963), p. 26.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 6, 165.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 819.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 820.

- ^ Warren (1964), pp. 130–135.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Testimony of Kenneth P. O'Donnell, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Blaine (2011), p. 196.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 25, 41.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 29.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 30.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 19–20, 30–38, 49.

- ^ "November 22, 1963: Death of the President". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 51.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 56–57.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 56, 58.

- ^ McAdams (2012)

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 110.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 49.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 58–60.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 39.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xxix, 458.

- ^ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, Vol VI. p. 29.

- ^ a b c d Testimony of Gov. John Bowden Connally, Jr, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 61.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 62.

- ^ Warren (1964), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Stokes (1979), pp. 41–46.

- ^ Testimony of Dr. Robert Roeder Shaw, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b Sabato (2013), p. 216.

- ^ a b Posner (1993), pp. 335–336.

- ^ Warren (1964), pp. 85–96.

- ^ a b Testimony of Clyde A. Haygood, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 63–64.

- ^ Warren (1964), pp. 111–115.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xx, 501.

- ^ Testimony of Bobby W. Hargis, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Summers (2013), p. 45.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 29.

- ^ a b Testimony of Clinton J. Hill, Special Agent, Secret Service, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Testimony of Mrs. John F. Kennedy, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Testimony of Mrs. John Bowden Connally, Jr, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 42.

- ^ Sabato (2013), p. 221.

- ^ Holland (2014)

- ^ Testimony of James Thomas Tague, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Trask (1994), pp. 38–40.

- ^ a b Trask (1994), p. 76.

- ^ Summers (2013), pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c Bugliosi (2007), p. 852.

- ^ Summers (2013), p. 35.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 898.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 898–899.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 80.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 81.

- ^ Testimony of Howard Brennan, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 64.

- ^ Summers (2013), p. 62.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 60.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 40.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 645.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 86–87.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 118.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 122.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 801.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 800.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 801−802.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 124.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 79.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 110−111, 151.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 122–124, 127.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 93–94.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 94–95, 101.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 150–152.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 153.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 161.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 85.

- ^ "Biographical sketch of Dr. George Gregory Burkley". Arlington National Cemetery.

- ^ a b Huber (2007), pp. 380–393.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 93.

- ^ "Walter Cronkite On The Assassination Of John F. Kennedy". NPR.

- ^ Daniel (2007), pp. 87, 88.

- ^ a b Boyd (2015), pp. 59, 62.

- ^ Ball (1982), p. 107.

- ^ a b c Jones (2013)

- ^ a b c d Kurtz (1982), p. 2.

- ^ a b Munson (2012)

- ^ a b Stafford (2012)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 110.

- ^ "President Lyndon B. Johnson takes Oath of Office, 22 November 1963". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 382.

- ^ Associated Press (1963), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Sabato (2013), p. 22.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Sabato (2013), p. 213.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 137–138.

- ^ "Oswald's Ghost". PBS

- ^ Burkley (1963)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 431.

- ^ a b Saner (2013)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 432

- ^ Kurtz (1982), p. 9.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 382–383.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 384.

- ^ Associated Press (1963), pp. 36–37, 56–57, 68.

- ^ The New York Times (2003), pp. 197–201.

- ^ Associated Press (1963), p. 40.

- ^ American Heritage (1964), pp. 52–53.

- ^ "Government Offices Closed by President". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b White (1965), p. 16.

- ^ NBC News (1966), pp. 106–107, 110, 114–115, 119–123, 133–134.

- ^ Neuman (2017)

- ^ Hoover (1963)

- ^ a b White (1965), p. 17.

- ^ Associated Press (1963), p. 93.

- ^ a b NBC News (1966), p. 126.

- ^ Associated Press (1963), pp. 94, 96.

- ^ Spivak (1963)

- ^ White (1965), p. 18.

- ^ "President John Fitzgerald Kennedy Gravesite". Arlington National Cemetery.

- ^ Fischer (2003), p. 206.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 450–451.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), pp. 451–452, 458–459.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 465.

- ^ Testimony of Jack Ruby, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 357.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 351, 1453.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 1019, 1484.

- ^ Trask (1994), pp. 59–61, 73.

- ^ a b Cosgrove (2011)

- ^ a b "How the JFK Zapruder film 'revolutionised' Hollywood". France24.

- ^ Pasternack (2011)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 371.

- ^ Inverne (2004)

- ^ Pasternack (2012)

- ^ Bugliosi (1998), p. 291.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 885.

- ^ Friedman (1963), p. 17.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 452.

- ^ a b c Rose (2015)

- ^ "George Jefferies Film". Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza.

- ^ "Newly released film of JFK before assassination". Associated Press.

- ^ MacAskill (2007)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 1045.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 886–887.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 887.

- ^ Warren (1964), p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Warren (1964), pp. 180–195.

- ^ a b Report of Capt. J. W. Fritz, Dallas Police Department, Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 113–116, 126, 123–132.

- ^ Reports of Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (1964), Warren Commission Hearings.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 164–165.

- ^ Pappalardo (2017)

- ^ a b c Bugliosi (2007), p. 338.

- ^ Associated Press (1963), p. 16.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 338–339.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 339.

- ^ Baluch (1963)

- ^ Roberts (1964)

- ^ Lewis (1964), p. 1.

- ^ Pomfret (1964), p. 17.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 359.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 454–457.

- ^ Sabato (2013), p. 136.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. xx.

- ^ Specter (2015)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 355, 455.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 455–456.

- ^ Baker (2023)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xxxii–xxxiii.

- ^ Posner (1993), p. x.

- ^ 'The Warren Report – Part 4 – Why Doesn't America Believe the Warren Report?". CBS.

- ^ Shenon (2014)

- ^ a b c Bugliosi (2007), p. 1347.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 1348.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 1348–1349.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 1399, 1401.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 1349.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 1351.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), pp. 371, 504, 1349.

- ^ Lane (1991), p. 221.

- ^ Davy (1999), p. 173.

- ^ Kirkwood (1992), p. 510.

- ^ Kirkwood (1968)

- ^ Kirkwood (1992), p. 557.

- ^ Kirkwood (1992), p. 511.

- ^ Ogg (2004), p. 137.

- ^ Ogg (2004), p. 139.

- ^ Evica (1992), p. 18.

- ^ Holland (2001)

- ^ "Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald". PBS.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 426–427.

- ^ a b c d Bugliosi (2007), p. 369.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xix, 369.

- ^ a b c "U.S. President's Commission on CIA Activities within the United States Files, [1947-74] 1975". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 1214.

- ^ a b Reitzes (2013)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 484.

- ^ "Timeline of the C.I.A.'s 'Family Jewels'". The New York Times

- ^ "Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities". US Senate.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 369–370.

- ^ a b c d Bugliosi (2007), p. 370.

- ^ a b c Kurtz (1982), p. 8.

- ^ Sabato (2013), p. 548.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 859.

- ^ Stokes (1979), pp. 9–16.

- ^ Stokes (1979), p. 2.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (1998), p. xxii.

- ^ a b Stokes (1979), pp. 483–511.

- ^ Stokes (1979), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Stokes (1979), pp. 239–261.

- ^ a b "Report of the Committee on Ballistic Acoustics". National Research Council.

- ^ a b Letter from Assistant Attorney General William F. Weld to Peter W. Rodino Jr., undated.

- ^ Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board, p. xxiii.

- ^ a b "National Archives Releases JFK Assassination Records". The National Archives.

- ^ Hornaday (2021)

- ^ Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board, Chapter 4.

- ^ Tunheim (2000).

- ^ Lardner Jr. (1998).

- ^ Stone (2013)

- ^ "Clarifying the Federal Record on the Zapruder Film and the Medical and Ballistics Evidence". Federation of American Scientists.

- ^ Bender (2013)

- ^ a b "Trump has no plan to block scheduled release of JFK records". Associated Press.

- ^ Shapira (2018)

- ^ Bender (2021)

- ^ "Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies on the Temporary Certification Regarding Disclosure of Information in Certain Records Related to the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy". The White House.

- ^ a b Matza (2022)

- ^ Fossum (2023)

- ^ Broderick (2008), p. 203.

- ^ "Majority in U.S. Still Believe JFK Killed in a Conspiracy: Mafia, federal government top list of potential conspirators". Gallup.

- ^ Chinni (2017)

- ^ Brenan, Megan (November 13, 2023). "Decades Later, Most Americans Doubt Lone Gunman Killed JFK". Gallup. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xiv, 974.

- ^ Posner (1993), p. ix.

- ^ a b Assassination Records Review Board (1998), p. 6.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2008), p. xlii.

- ^ Summers (2013), p. 238.

- ^ Patterson (2013)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 390, 1012.

- ^ "Oswald Didn't Kill Kennedy". New York Magazine.

- ^ Michaud (2011)

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 903–904.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xiv, 385, 440, 1057–1059.

- ^ Bugliosi (2008), p. 1012.

- ^ Carlson (2001)

- ^ Ogg (2004), p. 134.

- ^ Posner (1993), p. 333.

- ^ Ogg (2004), pp. 134–135.

- ^ Shenon (2023)

- ^ Sabato (2013), pp. 29–30.

- ^ Russo (2021)

- ^ a b "Minting a Legacy: The History of the Kennedy Half Dollar". NPS.

- ^ Witherspoon (1987), pp. 531—532.

- ^ Witherspoon (1987), p. 536.

- ^ Witherspoon (1987), pp. 536—538.

- ^ Bomboy (2022)

- ^ Fantova (1964), pp. 57–58, 62.

- ^ "History of Cape Canaveral" Spaceline.

- ^ "History of John F. Kennedy Space Center". NASA.

- ^ Robertson (1971)

- ^ "JFK International Marks Major Milestones in 2013 as 50th Anniversary of Airport Renaming Approaches". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

- ^ Naylor (2013)

- ^ Trask (1994), pp. iix.

- ^ Shahidullah (2015), p. 94.

- ^ Ball (1982), p. 105.

- ^ a b Brinkley (2013)

- ^ Dugan (2013)

- ^ Brinkley, David (2003). Brinkley's Beat. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40644-1.

- ^ White (1965), p. 6.

- ^ Dinneen, Joseph F. (November 24, 1963). "A Shock Like Pearl Harbor". The Boston Globe. p. 10.

- ^ "United in Remembrance, Divided over Policies". Pew Research Center. September 1, 2011.

- ^ Mudd 2008, p. 126

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xliii–xliv.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 996.

- ^ Wrone (2003), p. 47.

- ^ Scott (2013)

- ^ Cilento (2018) pp. 149—178.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 1356–1357; Lawson (2017); Thomas (1997)

- ^ Goldstein (1995); Vollman (1995); Jordison (2019)

- ^ Lawson (2011); Maslin (2011); Morris (2011)

- ^ "Music: Stravinsky Leads; Composer Conducts at Philharmonic Hall". The New York Times.; Lengel; Payne (1965)

- ^ a b Gates (1998)

- ^ Newfield (2002), pp. 176–178.

- ^ D'Angelo (2018); Margolick (2018); Paulson (2020)

- ^ Dettmar (2020); Hogan (2020); Petridis (2020)

- ^ a b "Dealey Plaza Historic District". NPS.

- ^ "Q: Why is it called The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza?". Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza.

- ^ a b Keen (2009)

- ^ "The Catafalque". Architect of the Capitol.

- ^ "Jack Ruby's Gun Sold For $220,000". Associated Press.

- ^ "Documents State JFK's Dallas Coffin Disposed At Sea". Associated Press.

Works cited

Books

- Boyd, John W. (2015). Parkland. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781467134002.

- United Press International; American Heritage (1964). Four Days: The Historical Record of the Death of President Kennedy. American Heritage Pub. Co. OCLC 923323127.

- Brinkley, David (2003). Brinkley's Beat: People, Places, and Events That Shaped My Time. Knopf. ISBN 9780375406447.

- Bugliosi, Vincent (2008). Four Days in November: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 9780393332155.

- ——— (2007). Reclaiming History. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 9780393045253.

- Cilento, Fabrizio (2018). The Ontology of Replay: The Zapruder Video and American Conspiracy Films. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783030064891.

- Daniel, Douglass K. (2007). Harry Reasoner: A Life in the News. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292714779.

- Fischer, Heinz-D; Fischer, Erika J. (2003). The Pulitzer Prize Archive: A History and Anthology of Award-Winning Materials in Journalism, Letters and Arts. Vol. 17 Complete Historical Handbook of the Pulitzer Prize System 1917–2000. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110939125.

- Hinckle, Warren; Turner, William W. (1981). The Fish is Red: The Story of the Secret War Against Castro. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060380038.

- Jones, Howard (2008). The Bay of Pigs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195173833.

- Kirkwood Jr., James (1992). American Grotesque: An Account of the Clay Shaw-Jim Garrison-Kennedy Assassination Trial in New Orleans. Harper Perennial. ISBN 9780060975234.

- Mudd, Roger (2008). The place to be: Washington, CBS, and the glory days of television news. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-576-4.

- The New York Times (2003). Semple, Robert B. Jr. (ed.). Four days in November: The Original Coverage of the John F. Kennedy Assassination. St. Martin's Press. OCLC 1149162285.

- Newfield, Jack (2002). Somebody's Gotta Tell It: A Journalist's Life on the Lines. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312269005.

- NBC News (1966). There Was a President. Random House. ASIN B000GOFC9O.

- Pett, Saul; Moody, Sidney C.; Henshaw, Tom (1963). The Torch Is Passed: The Associated Press Story of the Death of a President. Associated Press. OCLC 13554948.

- Posner, Gerald (1993). Case Closed. Random House. ISBN 9780679418252.

- Shahidullah, Shahid M. (2015). Crime Policy in America: Laws, Institutions, and Programs. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780761866589.

- Sabato, Larry (2013). The Kennedy Half-Century: The Presidency, Assassination, and Lasting Legacy of John F. Kennedy. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 9781620402801.

- Summers, Anthony (2013). Not in Your Lifetime. Open Road. ISBN 9781480435483.

- Trask, Richard B. (1994). Pictures of the Pain: Photography and the Assassination of President Kennedy. Yeoman Press. ISBN 9780963859501.

- White, Theodore H. (1965). The Making of the President, 1964. Atheneum Publishers. ASIN B003SAGZMQ.

- Wrone, David R. (2003). The Zapruder Film: Reframing JFK's Assassination. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700612918.

Government and institutional documents and reports

- Hoover, J. Edgar (December 1, 1963). Reaction of Soviet and Communist Party Officials to JFK Assassination (PDF) (Report). National Archives.

- Warren, Earl (1964). Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. United States Government Printing Office. ASIN B0065RJ63E.

- Clark, Ramsey (1968). 1968 Panel Review of Photographs, X-Ray Films, Documents and Other Evidence Pertaining to the Fatal Wounding of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas (Report). United States Government Printing Office.

- Stokes, Louis (1979). Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives (Report). United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on April 3, 2020.

- HSCA Appendix to Hearings (Report). Archived from the original on July 1, 2022 – via History Matters Archive.

- Assassination Records Review Board (September 30, 1998). "Chapter 1: The Problem of Secrecy and the JFK Act" (PDF). Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board. United States Government Printing Office. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021.

- Report of the Committee on Ballistic Acoustics. National Research Council. 1982. doi:10.17226/10264. ISBN 9780309253727. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013.

- Assassination Records Review Board (September 30, 1998). Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board (PDF) (Report). United States Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021.

Warren Commission documents, exhibits, and testimonies

- Testimony of Gov. John Bowden Connally, Jr. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. IV. pp. 129–146. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Testimony of Mrs. John Bowden Connally, Jr. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. IV. pp. 146–149. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Testimony of Mrs. John F. Kennedy. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. V. June 5, 1964. pp. 178–181. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Testimony of Dr. Robert Roeder Shaw. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. IV. pp. 101–117. Archived from the original on July 20, 2013 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Notes of interview of Lee Harvey Oswald — Certified military pay records for Lee Harvey Oswald for the period October 24, 1956, to September 11, 1959. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. 22. p. 705. Archived from the original on October 19, 2007 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Warren Commission Hearings, Folsom Exhibit No. 1 (cont'd) (Report). Vol. XIX Folsom. p. 734. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012.

- Testimony of James Thomas Tague. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. VII. July 23, 1964. pp. 552–558. Archived from the original on July 20, 2013 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Testimony of Clinton J. Hill, Special Agent, Secret Service. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. II. pp. 132–144. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Testimony of Bobby W. Hargis. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. VI. April 8, 1964. pp. 293–296. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- Testimony of Clyde A. Haygood. Warren Commission Hearings (Report). Vol. VI. April 9, 1964. pp. 296–302. Archived from the original on July 20, 2013 – via Assassination Archives and Research Center.