Abbey Road: Difference between revisions

LCossyYkIt (talk | contribs) m Not much Tags: Reverted Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Reverted image to original album cover. (Undid revision 1254214953 by LCossyYkIt (talk)) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| type = studio |

| type = studio |

||

| artist = [[the Beatles]] |

| artist = [[the Beatles]] |

||

| cover = |

| cover = Beatles - Abbey Road.jpg |

||

| caption = |

| caption = |

||

| alt = The cover of Abbey Road has no printed words. It is a photo of the Beatles, in side view, crossing the street in single file. |

| alt = The cover of Abbey Road has no printed words. It is a photo of the Beatles, in side view, crossing the street in single file. |

||

Revision as of 23:24, 29 October 2024

| Abbey Road | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 26 September 1969 | |||

| Recorded | 22 February – 20 August 1969 | |||

| Studio | EMI, Olympic and Trident, London | |||

| Genre | Rock[1] | |||

| Length | 47:03 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Producer | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| The Beatles North American chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Abbey Road | ||||

| ||||

Abbey Road is the eleventh studio album by the English rock band the Beatles, released on 26 September 1969, by Apple Records. It is the last album the group recorded,[2] although Let It Be (1970) was the last album completed before the band's break-up in April 1970.[3] It was mostly recorded in April, July, and August 1969, and topped the record charts in both the United States and the United Kingdom. A double A-side single from the album, "Something" / "Come Together", was released in October, which also topped the charts in the US.

Abbey Road incorporates styles such as rock, pop, blues, and progressive rock,[4] and makes prominent use of the Moog synthesiser and guitar played through a Leslie speaker unit. It is also notable for having a long medley of songs on side two that have subsequently been covered as one suite by other notable artists. The album was recorded in a more collegial atmosphere than the Get Back / Let It Be sessions earlier in the year, but there were still significant confrontations within the band, particularly over Paul McCartney's song "Maxwell's Silver Hammer", and John Lennon did not perform on several tracks. By the time the album was released, Lennon had left the group, though this was not publicly announced until McCartney also quit the following year.

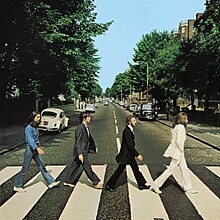

Although Abbey Road was an instant commercial success, it received mixed reviews upon release. Some critics found its music inauthentic and criticised the production's artificial effects. By contrast, critics today view the album as one of the Beatles' best and one of the greatest albums of all time. George Harrison's two songs on the album, "Something" and "Here Comes the Sun", are considered among the best he wrote for the group. The album's cover, featuring the Beatles walking across the zebra crossing outside of Abbey Road Studios (then officially named EMI Studios), is one of the most famous and imitated of all time.

Background

After the recording sessions for the proposed Get Back album, Paul McCartney suggested to producer George Martin that the group get together and make an album "the way we used to do it",[5] free of the conflict that had begun during sessions for The Beatles (also known as the "White Album"). Martin agreed, but on the strict condition that all the group—particularly John Lennon—allow him to produce the record in the same manner as earlier albums and that discipline would be adhered to.[6] No one was sure that the work would be the group's last, though George Harrison later recalled that "it felt as if we were reaching the end of the line".[7]

Production

Recording history

The first sessions for Abbey Road began on 22 February 1969, only three weeks after the Get Back sessions, in Trident Studios. There, the group recorded a backing track for "I Want You (She's So Heavy)" with Billy Preston accompanying them on Hammond organ.[2] No further group recording occurred until April because of Ringo Starr's commitments on the film The Magic Christian.[8] After a small amount of work that month and a session for "You Never Give Me Your Money" on 6 May, the group took an eight-week break before recommencing on 2 July.[9] Recording continued through July and August, and the last backing track, for "Because", was taped on 1 August.[10] Overdubs continued through the month, with the final sequencing of the album coming together on 20 August – the last time all four Beatles were present in a studio together.[3]

McCartney, Starr and Martin have reported positive recollections of the sessions,[11] while Harrison said, "we did actually perform like musicians again".[12] Lennon and McCartney had enjoyed working together on the non-album single "The Ballad of John and Yoko" in April, sharing friendly banter between takes, and some of this camaraderie carried over to the Abbey Road sessions.[13] Nevertheless, there was a significant amount of tension in the group. According to Ian MacDonald, McCartney had an acrimonious argument with Lennon during the sessions. Lennon's wife Yoko Ono had become a permanent presence at Beatles recordings, and clashed with other members.[11] Halfway through recording in June, Lennon and Ono were involved in a car accident. A doctor told Ono to rest in bed, so Lennon had one installed in the studio so she could observe the recording process from there.[6]

During the sessions, Lennon expressed a desire to have all of his songs on one side of the album, and McCartney's on the other.[12] The album's two halves represented a compromise: Lennon wanted a traditional release with distinct and unrelated songs, while McCartney and Martin wanted to continue their thematic approach from Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band by incorporating a medley. Lennon ultimately said that he disliked Abbey Road as a whole and felt that it lacked authenticity, calling McCartney's contributions "[music] for the grannies to dig" and not "real songs",[14] and describing the medley as "junk ... just bits of songs thrown together".[15]

Technical aspects

Abbey Road was recorded on eight-track reel-to-reel tape machines[11] rather than the four-track machines that were used for earlier Beatles albums such as Sgt Pepper, and was the first Beatles album not to be issued in mono anywhere in the world.[16] The album makes prominent use of guitar played through a Leslie speaker, and of the Moog synthesiser. The Moog is not merely used as a background effect but sometimes plays a central role, as in "Because", where it is used for the middle eight. It is also prominent on "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" and "Here Comes the Sun". The synthesiser was introduced to the band by Harrison, who acquired one in November 1968 and used it to create his album Electronic Sound.[11] Starr made more prominent use of the tom-toms on Abbey Road, later saying the album was "tom-tom madness ... I went nuts on the toms."[17]

Abbey Road was also the first and only Beatles album to be entirely recorded through a solid-state transistor mixing desk, the TG12345 Mk I, as opposed to earlier tube (thermionic valve)-based REDD desks. The TG console also allowed better support for eight-track recording, facilitating the Beatles' considerable use of overdubbing.[18] Emerick recalls that the TG desk used to record the album had individual limiters and compressors on each audio channel[19] and noted that the overall sound was "softer" than the earlier tube (valve) desks.[20] In his study of the role of the TG12345 in the Beatles' sound on Abbey Road, the music historian Kenneth Womack observes that "the expansive sound palette and mixing capabilities of the TG12345 enabled George Martin and Geoff Emerick to imbue the Beatles' sound with greater definition and clarity. The warmth of solid-state recording also afforded their music with brighter tonalities and a deeper low end that distinguished Abbey Road from the rest of their corpus, providing listeners with an abiding sense that the Beatles' final long-player was markedly different."[21]

Alan Parsons worked as an assistant engineer on the album. He later went on to engineer Pink Floyd's landmark album The Dark Side of the Moon and produce many popular albums himself with the Alan Parsons Project.[22] John Kurlander also assisted on many of the sessions, and went on to become a successful engineer and producer, most noteworthy for his success on the scores for the Lord of the Rings film trilogy.[23]

Songs

Side one

"Come Together"

"Come Together" was an expansion of "Let's Get It Together", a song Lennon originally wrote for Timothy Leary's California gubernatorial campaign against Ronald Reagan.[24] A rough version of the lyrics for "Come Together" was written at Lennon's and Ono's second bed-in event in Montreal.[25]

The biographer Jonathan Gould suggested that the song has only a single "pariah-like protagonist" and Lennon was "painting another sardonic self-portrait".[26] MacDonald has suggested that the "juju eyeballs" has been claimed to refer to Dr John and "spinal cracker" to Ono.[27] The song was later the subject of a lawsuit brought against Lennon by Morris Levy because the opening line in "Come Together" – "Here come old flat-top" – was admittedly lifted from a line in Chuck Berry's "You Can't Catch Me". A settlement was reached in 1973 in which Lennon promised to record three songs from Levy's publishing catalogue for his next album.[28]

"Come Together" was later released as a double A-side single with "Something".[29] In the liner notes to the compilation album Love, Martin described the track as "a simple song but it stands out because of the sheer brilliance of the performers".[30]

"Something"

Harrison was inspired to write "Something" during sessions for the White Album by listening to his label-mate James Taylor's "Something in the Way She Moves" from his album James Taylor.[31] After the lyrics were refined during the Let It Be sessions (tapes reveal Lennon giving Harrison some songwriting advice during its composition), the song was initially given to Joe Cocker, but was subsequently recorded for Abbey Road. Cocker's version appeared on his album Joe Cocker! that November.[32]

"Something" was Lennon's favourite song on the album, and McCartney considered it the best song Harrison had written.[33] Though the song was written by Harrison, Frank Sinatra once commented that it was his favourite Lennon–McCartney composition[34] and "the greatest love song ever written".[35] Lennon contributed piano to the recording and while most of the part was removed, traces of it remain in the final cut, notably on the middle eight, before Harrison's guitar solo.[32]

The song was issued as a double A-side single with "Come Together" in October 1969 and topped the US charts for one week, becoming the Beatles' first number-one single that was not a Lennon–McCartney composition.[36] It was also the first Beatles single from an album already released in the UK.[nb 1] Apple's Neil Aspinall filmed a promotional video, which combined separate footage of the Beatles and their wives.[38]

"Maxwell's Silver Hammer"

"Maxwell's Silver Hammer", McCartney's first song on the album, was first performed by the Beatles during the Let It Be sessions (as seen in the film). He wrote the song after the group's trip to India in 1968 and wanted to record it for the White Album, but it was rejected by the others as "too complicated".[26]

The recording was fraught with tension between band members, as McCartney annoyed others by insisting on a perfect performance. The track was the first Lennon was invited to work on following his car accident, but he hated it and declined to do so.[39] According to engineer Geoff Emerick, Lennon said it was "more of Paul's granny music" and left the session.[40] He spent the next two weeks with Ono and did not return to the studio until the backing track for "Come Together" was laid down on 21 July.[24] Harrison was also tired of the song, saying "we had to play it over and over again until Paul liked it. It was a real drag". Starr was more sympathetic to the song. "It was granny music", he admitted, "but we needed stuff like that on our album so other people would listen to it".[40] Longtime roadie Mal Evans played the anvil sound in the chorus.[41] This track also makes use of Harrison's Moog synthesiser, played by McCartney.[39]

"Oh! Darling"

"Oh! Darling" was written by McCartney in a doo-wop style, like contemporary work by Frank Zappa.[42] It was tried at the Get Back sessions, and a version appears on Anthology 3.[nb 2] It was subsequently re-recorded in April, with overdubs in July and August.[42]

McCartney attempted recording the lead vocal only once a day. He said: "I came into the studios early every day for a week to sing it by myself because at first my voice was too clear. I wanted it to sound as though I'd been performing it on stage all week."[44] Lennon thought he should have sung it, remarking that it was more his style.[45]

"Octopus's Garden"

As was the case with most of the Beatles' albums, Starr sang lead vocal on one track. "Octopus's Garden" is his second and last solo composition released on any album by the band. It was inspired by a trip with his family to Sardinia aboard Peter Sellers's yacht after Starr left the band for two weeks during the sessions for the White Album. Starr received a full songwriting credit and composed most of the lyrics, although the song's melodic structure was partly written in the studio by Harrison.[46] The pair would later collaborate as writers on Starr's solo singles "It Don't Come Easy", "Back Off Boogaloo" and "Photograph".[47]

"I Want You (She's So Heavy)"

"I Want You (She's So Heavy)" was written by Lennon about his relationship with Ono,[2] and he made a deliberate choice to keep the lyrics simple and concise.[48] Author Tom Maginnis writes that the song had a progressive rock influence, with its unusual length and structure, repeating guitar riff, and white noise effects, though he noted the "I Want You" section has a straightforward blues structure.[49][50]

The finished song is a combination of two different recording attempts. The first attempt occurred in February 1969, almost immediately after the Get Back / Let It Be sessions with Billy Preston. This was subsequently combined with a second version made during the Abbey Road sessions proper in April. The two sections together ran to nearly eight minutes, making it the Beatles' second-longest released track.[nb 3] Lennon used Harrison's Moog synthesiser with a white noise setting to create a "wind" effect that was overdubbed on the second half of the track.[2] During the final edit, Lennon told Emerick to "cut it right there" at 7 minutes and 44 seconds, creating a sudden, jarring silence that concludes the first side of Abbey Road (the recording tape would have run out within 20 seconds as it was).[51] The final mixing and editing of the track occurred on 20 August 1969, the last day on which all four Beatles were together in the studio.[52]

Side two

"Here Comes the Sun"

"Here Comes the Sun" was written by Harrison in Eric Clapton's garden in Surrey during a break from stressful band business meetings.[53] The basic track was recorded on 7 July 1969. Harrison sang lead and played acoustic guitar, McCartney provided backing vocals and played bass, and Starr played the drums.[51] Lennon was still recovering from his car accident and did not perform on the track. Martin provided an orchestral arrangement in collaboration with Harrison, who overdubbed a Moog synthesiser part on 19 August, immediately before the final mix.[53]

Though not released as a single, the song attracted attention and critical praise, and was included on the compilation 1967–1970. It has been featured several times on BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs, having been chosen by Sandie Shaw, Jerry Springer, Boris Johnson and Elaine Paige.[54] The Daily Telegraph's Martin Chilton said it was "almost impossible not to sing along to".[55] Since digital downloads have become eligible to chart, it reached number 56 in 2010 after the Beatles' back catalogue was released on iTunes.[56]

Harrison recorded a guitar solo for this track that did not appear in the final mix. It was rediscovered in 2012, and footage of Martin and Harrison's son Dhani listening to it in the studio was released on the DVD of Living in the Material World.[57]

"Because"

"Because" was inspired by Lennon listening to Ono playing Ludwig van Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata" on the piano. He recalled he was "lying on the sofa in our house, listening to Yoko play ... Suddenly, I said, 'Can you play those chords backward?' She did, and I wrote 'Because' around them."[58] The track features three-part harmonies by Lennon, McCartney and Harrison, which were then triple-tracked to give nine voices in the final mix. The group considered the vocals to be some of the hardest and most complex they attempted. Harrison played the Moog synthesiser, and Martin played the harpsichord that opens the track.[10]

Medley

The remainder of side two consists of a 16-minute medley of eight tracks consisting of a number of short songs and song fragments (known during the recording sessions as "The Long One"),[59][60][61] recorded over July and August and blended into a suite by McCartney and Martin.[62] Some songs were written (and originally recorded in demo form) during sessions for the White Album and Get Back / Let It Be, which later appeared on Anthology 3.[63] While the idea for the medley was McCartney's, Martin claims credit for some structure, adding he "wanted to get John and Paul to think more seriously about their music".[7]

The first track recorded for the medley was the opening number, "You Never Give Me Your Money". McCartney has said the band's dispute over Allen Klein and what McCartney viewed as Klein's empty promises were the inspiration for the song's lyrics.[64] However, MacDonald doubts this, given that the backing track, recorded on 6 May at Olympic Studios, predated the worst altercations between Klein and McCartney. The track is a suite of varying styles, ranging from a piano-led ballad at the start to arpeggiated guitars at the end.[65] Both Harrison and Lennon provided guitar solos, with Lennon playing the solos at the end of the track.[66]

This song transitions into Lennon's "Sun King" which, like "Because", showcases Lennon, McCartney and Harrison's triple-tracked harmonies. Following it are Lennon's "Mean Mr. Mustard" (written during the Beatles' 1968 trip to India) and "Polythene Pam".[67] These in turn are followed by four McCartney songs, "She Came In Through the Bathroom Window" (written after a fan entered McCartney's residence via his bathroom window),[68] "Golden Slumbers" (based on Thomas Dekker's 17th-century poem set to new music),[69] "Carry That Weight" (reprising elements from "You Never Give Me Your Money", and featuring chorus vocals from all four Beatles), and closing with "The End".[70]

"The End" features Starr's only drum solo in the Beatles' catalogue (the drums are mixed across two tracks in "true stereo", unlike most releases at that time where they were hard-panned left or right). Fifty-four seconds into the song are 18 bars of lead guitar: the first two bars are played by McCartney, the second two by Harrison, and the third two by Lennon, and the sequence is repeated two more times.[71] Harrison suggested the idea of a guitar solo in the track, Lennon decided they should trade solos and McCartney elected to go first. The solos were cut live against the existing backing track in one take.[7] Immediately after Lennon's third and final solo, the piano chords of the final part of the song begin. The song ends with the memorable final line, "And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make". This section was taped separately from the first and required the piano to be re-recorded by McCartney, which was done on 18 August.[71] An alternative version of the song, with Harrison's lead guitar solo played against McCartney's (and Starr's drum solo heard in the background), appears on the Anthology 3 album and the 2012 digital-only compilation album Tomorrow Never Knows.[72]

Musicologist Walter Everett interprets that most of the lyrics on side two's medley deal with "selfishness and self-gratification – the financial complaints in 'You Never Give Me Your Money,' the miserliness of Mr. Mustard, the holding back of the pillow in 'Carry That Weight,' the desire that some second person will visit the singer's dreams – perhaps the 'one sweet dream' of 'You Never Give Me Your Money'? – in 'The End.'"[73] Everett adds that the medley's "selfish moments" are played in the context of the tonal centre of A, while "generosity" is expressed in songs where C major is central.[73] The medley concludes with a "great compromise in the 'negotiations'" in "The End", which serves as a structurally balanced coda. In response to the repeated A-major choruses of "love you", McCartney sings in realisation that there is as much self-gratifying love ("the love you take") as there is of the generous love ("the love you make"), in A major and C major, respectively.[73]

"Her Majesty"

"Her Majesty" was recorded by McCartney on 2 July when he arrived before the rest of the group at Abbey Road. It was originally included in a rough mix of the side two medley (and officially available in this form for the first time on the album's 3CD Super Deluxe edition box set), appearing between "Mean Mr. Mustard" and "Polythene Pam". McCartney disliked the way the medley sounded when it included "Her Majesty", so he asked for it to be cut. The second engineer, John Kurlander, had been instructed by George Martin not to throw out anything, so after McCartney left, he attached the track to the end of the master tape after 20 seconds of silence. The tape box bore an instruction to leave "Her Majesty" off the final product, but the next day when mastering engineer Malcolm Davies received the tape, he (also trained not to throw anything away) cut a playback lacquer of the whole sequence, including "Her Majesty". The Beatles liked this effect and included it on the album.[74]

"Her Majesty" opens with the final, crashing chord of "Mean Mr. Mustard", while the final note remained buried in the mix of "Polythene Pam", as a result of being snipped off the reel during a rough mix of the medley on 30 July. The medley was subsequently mixed again from scratch although the song was not touched again and still appears in its rough mix on the album.[74]

Original US and UK pressings of Abbey Road do not list "Her Majesty" on the album's cover nor on the record label,[75] making it a hidden track. The song title appears on the inlay card and disc of the 1987 remastered CD reissue, as track 17.[76] It also appears on the sleeve, booklet and disc of the 2009 remastered CD reissue,[77] but not on the cover or record label of the 2012 vinyl reissue or the 2019 remix of the album.[78]

Unreleased material

Three days after the session for "I Want You (She's So Heavy)", Harrison recorded solo demos of "All Things Must Pass" (which became the title track of his 1970 triple album), "Something" and "Old Brown Shoe".[79] The latter was re-recorded by the Beatles in April 1969 and issued as the B-side of "The Ballad of John and Yoko" the following month. All three of these Harrison demos were later featured on Anthology 3.[80]

During the sessions for the medley, McCartney recorded "Come and Get It", playing all the instruments. It was assumed to be a demo recording for another artist[81] but McCartney later said that he originally intended to put it on Abbey Road.[82] It was instead covered by Badfinger, while McCartney's original recording appeared on Anthology 3.

The original backing track to "Something", featuring a piano-led coda,[32] and "You Never Give Me Your Money", which leads into a fast rock-n-roll jam session,[65] have appeared on bootlegs.[83][84]

Cover photo

Apple Records creative director Kosh designed the album cover. It is the only original UK Beatles album sleeve to show neither the artist name nor the album title on its front cover, which was Kosh's idea, despite EMI saying the record would not sell without this information. He later explained that "we didn't need to write the band's name on the cover [...] They were the most famous band in the world".[85] The front cover was a photograph of the group walking on a zebra crossing, based on ideas that McCartney sketched,[86][nb 4] and taken on 8 August 1969 outside EMI Studios on Abbey Road. At 11:35 that morning, photographer Iain Macmillan was given only ten minutes to take the photo while he stood on a step-ladder and a policeman held up traffic behind the camera. Macmillan took six photographs, which McCartney examined with a magnifying glass before deciding which would be used on the album sleeve.[85][87]

In the image selected by McCartney, the group walk across the street in single file from left to right, with Lennon leading, followed by Starr, McCartney and Harrison. McCartney is barefoot and out of step with the others. Except for Harrison, the group are wearing suits designed by Tommy Nutter.[88] A white Volkswagen Beetle is to the left of the picture, parked next to the zebra crossing, which belonged to one of the people living in the block of flats across from the recording studio. After the album was released, the number plate (LMW 281F) was repeatedly stolen from the car.[nb 5] In 2004, news sources published a claim made by retired American salesman Paul Cole that he was the man standing on the pavement to the right of the picture.[91]

Release

In mid-1969, Lennon formed a new group, the Plastic Ono Band, in part because the Beatles had rejected his song "Cold Turkey".[92] While Harrison worked with such artists as Leon Russell, Doris Troy, Preston and Delaney & Bonnie through to the end of the year,[93] McCartney took a hiatus from the group after his daughter Mary was born on 28 August.[86] On 20 September, six days before Abbey Road was released, Lennon told McCartney, Starr, and business manager Allen Klein (Harrison was not present) that he "wanted a divorce"[94] from the group. Apple released "Something" backed with "Come Together" in the US on 6 October 1969.[95] Release of the single in the UK followed on 31 October,[96] while Lennon released the Plastic Ono Band's "Cold Turkey" the same month.[97]

The Beatles did little promotion of Abbey Road directly, and no public announcement was made of the band's split until McCartney announced he was leaving the group in April 1970.[98] By this time, the Get Back project (by now retitled Let It Be) had been re-examined, with overdubs and mixing sessions continuing into 1970. Therefore, Let It Be became the last album to be finished and released by the Beatles, although its recording had begun before Abbey Road.[3]

Abbey Road sold four million copies in its first two months of release.[99] In the UK, the album debuted at number one, where it remained for 11 weeks before being displaced for one week by the Rolling Stones' Let It Bleed. The following week (which was Christmas), Abbey Road returned to the top for another six weeks (completing a total of 17 weeks) before being displaced by Led Zeppelin's Led Zeppelin II.[100][101] Altogether, it spent 81 weeks on the UK albums chart.[102] The album also performed strongly overseas. In the US, it spent 11 weeks at number one on the Billboard Top LPs chart.[103] It was the National Association of Recording Merchandisers (NARM) best-selling album of 1969.[104] In Japan, it was one of the longest-charting albums to date, remaining in the top 100 for 298 weeks during the 1970s.[105]

Critical reception

Contemporary

Abbey Road initially received mixed reviews from music critics,[106] who criticised the production's artificial sounds and viewed its music as inauthentic.[107] William Mann of The Times said that the album will "be called gimmicky by people who want a record to sound exactly like a live performance",[107] although he considered it to be "teem[ing] with musical invention" and added: "Nice as 'Come Together' and Harrison's 'Something' are – they are minor pleasures in the context of the whole disc ... Side Two is marvellous ..."[108] Ed Ward of Rolling Stone called the album "complicated instead of complex" and felt that the Moog synthesiser "disembodies and artificializes" the band's sound, adding that they "create a sound that could not possibly exist outside the studio".[107] While he found the medley on side two to be their "most impressive music" since Rubber Soul, Nik Cohn of The New York Times said that, "individually", the album's songs are "nothing special".[109] Albert Goldman of Life magazine wrote that Abbey Road "is not one of the Beatles' great albums" and, despite some "lovely" phrases and "stirring" segues, side two's suite "seems symbolic of the Beatles' latest phase, which might be described as the round-the-clock production of disposable music effects".[110] John Gabree of the magazine High Fidelity wrote, of the album, "what's to say? If you like the Beatles, you'll like the record. If you have your doubts, this will do nothing to allay them. Of course, as someone just said, they do have 'something.'"[111]

Conversely, Chris Welch wrote in Melody Maker: "the truth is, their latest LP is just a natural born gas, entirely free of pretension, deep meanings or symbolism ... While production is simple compared to past intricacies, it is still extremely sophisticated and inventive."[112] Derek Jewell of The Sunday Times found the album "refreshingly terse and unpretentious", and although he lamented the band's "cod-1920s jokes (Maxwell's Silver Hammer) and ... Ringo's obligatory nursery arias (Octopus's Garden)", he considered that Abbey Road "touches higher peaks than did their last album".[108] John Mendelsohn, writing for Rolling Stone, called it "breathtakingly recorded" and praised side two especially, equating it to "the whole of Sgt. Pepper" and stating, "That the Beatles can unify seemingly countless musical fragments and lyrical doodlings into a uniformly wonderful suite ... seems potent testimony that no, they've far from lost it, and no, they haven't stopped trying."[113] Don Heckman of Stereo Review named the album one of the "Best Recordings of the Month" of January 1970, remarking that it was "better than 'The Beatles' or 'Magical Mystery Tour,' and probably the equal of 'Sgt. Pepper'", adding, "I suppose I haven't really come up with any new compliments for the Beatles-not that they need them. But I hope I have at least persuaded you to hear 'Abbey Road.' You'll find it a happy experience."[114]

While covering the Rolling Stones' 1969 American tour for The Village Voice, Robert Christgau reported from a meeting with Greil Marcus in Berkeley that "opinion has shifted against the Beatles. Everyone is putting down Abbey Road." Shortly afterwards, in Los Angeles, he wrote that his colleague Ellen Willis had grown to love the record, adding: "Damned if she isn't right – flawed but fine. Because the world is round it turns her on. Charlie Watts tells us he likes it too."[115]

Retrospective

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The A.V. Club | A[117] |

| Consequence of Sound | A+[118] |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | |

| Paste | 100/100[122] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[123] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Q Magazine | |

Many critics have since cited Abbey Road as the Beatles' greatest album.[126] In a retrospective review, Nicole Pensiero of PopMatters called it "an amazingly cohesive piece of music, innovative and timeless".[127] Mark Kemp of Paste viewed the album as being "among the Beatles' finest works, even if it foreshadows the cigarette-lighter-waving arena rock that technically skilled but critically maligned artists from Journey to Meatloaf would belabor throughout the '70s and '80s".[122] Neil McCormick of The Daily Telegraph dubbed it the Beatles' "last love letter to the world" and praised its "big, modern sound", calling it "lush, rich, smooth, epic, emotional and utterly gorgeous".[119]

AllMusic's Richie Unterberger felt that the album shared Sgt. Pepper's "faux-conceptual forms", but had "stronger compositions", and wrote of its standing in the band's catalogue: "Whether Abbey Road is the Beatles' best work is debatable, but it's certainly the most immaculately produced (with the possible exception of Sgt. Pepper) and most tightly constructed."[116] Ian MacDonald gave a mixed opinion of the album, noting that several tracks had been written at least a year previously, and would possibly have been unsuitable without being integrated into the medley on side two. He did, however, praise the production, particularly the sound of Starr's bass drum.[11]

Abbey Road has received high rankings in several "greatest albums of all time" lists and polls by critics and publications.[128][129][130] It was voted number 8 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's book All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[131] Time included it in their 2006 list of the All-Time 100 Albums.[132] In 2009, readers of Rolling Stone named Abbey Road the greatest Beatles album.[128][133] In 2020, the magazine ranked the album at number 5 on its list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time", the highest Beatles record on the list;[134] a previous version of the list from 2012 had ranked it at number 14.[135] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[136]

Legacy

Abbey Road crossing and "Paul is dead"

The front cover image of the Beatles on the Abbey Road crossing has become one of the most famous and imitated in recording history.[85] The crossing is a popular destination for Beatles fans,[85] and a webcam has operated there since 2011.[137] In December 2010, the crossing was given grade II listed status for its "cultural and historical importance"; the Abbey Road studios themselves had been given similar status earlier in the year.[138]

Shortly after the album's release, the cover became part of the "Paul is dead" conspiracy theory that was spreading across college campuses in the US. According to followers of the rumour, the cover depicted the Beatles walking out of a cemetery in a funeral procession. The procession was led by Lennon dressed in white as a religious figure; Starr was dressed in black as the undertaker; McCartney, out of step with the others, was a barefoot corpse; and Harrison dressed in denim was the gravedigger. The left-handed McCartney is holding a cigarette in his right hand, indicating that he is an impostor, and part of the number plate on the Volkswagen parked on the street is 281F (misread as 28IF), meaning that McCartney would have been 28 if he had lived – despite the fact that he was only 27 at the time of the photo and subsequent release of the record.[139][140] The escalation of the "Paul is dead" rumour became the subject of intense analysis on mainstream radio and contributed to Abbey Road's commercial success in the US.[141] Lennon was interviewed in London by New York's WMCA, and he ridiculed the rumour but conceded that it was invaluable publicity for the album.[142]

The cover image has been parodied on several occasions, including by Booker T. & the M.G.'s McLemore Avenue (1970), Kanye West's Late Orchestration (2006) and by McCartney on his 1993 live album Paul Is Live.[143][144] On the cover of its October 1977 issue, the satirical magazine National Lampoon depicted the four Beatles flattened along the zebra crossing, with a road roller driving away up the street.[145] The Red Hot Chili Peppers' The Abbey Road E.P. parodies the cover, with the band walking near-naked across a similar zebra crossing.[146] In 2003, several US poster companies airbrushed McCartney's cigarette out of the image without permission from Apple or McCartney.[147] In 2013, Kolkata Police launched a traffic safety awareness advertisement against jaywalking, using the cover and a caption that read: "If they can, why can't you?"[148]

Cover versions and influence

The songs on Abbey Road have been covered many times and the album itself has been covered in its entirety. One month after Abbey Road's release, George Benson recorded a cover version of the album called The Other Side of Abbey Road.[149] Later in 1969 Booker T. & the M.G.'s recorded McLemore Avenue (the location in Memphis of Stax Records) which covered the Abbey Road songs and had a similar cover photo.[150]

While matching albums such as Sgt. Pepper in terms of popularity, Abbey Road failed to repeat the Beatles' earlier achievements in galvanising their rivals to imitate them.[107] In author Peter Doggett's description, "Too contrived for the rock underground to copy, too complex for the bubblegum pop brigade to copy, the album influenced no one – except [Paul McCartney]", who spent years trying to emulate its scope in his solo career.[107] Writing for Classic Rock in 2014, Jon Anderson of the progressive rock band Yes said his group were constantly influenced by the Beatles from Revolver onwards, but it was the feeling that side two was "one complete idea" that inspired him to create long-form pieces of music.[151][nb 6]

Several artists have covered some or all of the side-two medley, including Phil Collins (for the Martin/Beatles tribute album In My Life),[152] The String Cheese Incident,[153] Transatlantic[154] and Tenacious D (who performed the medley with Phish keyboardist Page McConnell).[155] Furthur, a jam band including former Grateful Dead members Bob Weir and Phil Lesh, played the entire Abbey Road album during its Spring Tour 2011. It began with a "Come Together" opener at Boston on 4 March and ended with the entire medley in New York City on 15 March, including "Her Majesty" as an encore.[156]

Continued sales and reissues

In June 1970, Allen Klein reported that Abbey Road was the Beatles' best-selling album in the US with sales of about five million.[157] By 1992, Abbey Road had sold nine million copies.[99] The album became the ninth-most downloaded on the iTunes Store a week after it was released there on 16 November 2010.[56] A CNN report stated it was the best-selling vinyl album of 2011.[158] It is the first album from the 1960s to sell over five million albums since 1991 when Nielsen SoundScan began tracking sales.[159] In the US, the album had sold 7,177,797 copies by the end of the 1970s.[160] As of 2011[update], the album had sold over 31 million copies worldwide and is one of the band's best-selling albums.[161] In October 2019, Abbey Road re-entered the UK charts, again hitting number one.[162]

Abbey Road has remained in print since its first release in 1969. The original album was released on 26 September in the UK[163] and 1 October in the US on Apple Records.[164] It was reissued as a limited edition picture disc on vinyl in the US by Capitol on 27 December 1978,[165] while a CD reissue of the album was released in 1987, with a remastered version appearing in 2009.[166] The remaster included additional photographs with additional liner notes and the first, limited edition, run also included a short documentary about the making of the album.[167]

In 2001, Abbey Road was certified 12× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[168] The album continues to be reissued on vinyl. It was included as part of the Beatles' Collector's Crate series in September 2009[169] and saw a remastered LP release on 180-gram vinyl in 2012.[170]

A super deluxe version of the album, which featured new mixes by Giles Martin, was released in September 2019 to celebrate the original album's 50th anniversary.

As of October 2019, Abbey Road has sold 2,240,608 pure sales in the United Kingdom with all consumed sales standing at 2,327,230 units. Post 1994 sales stand at 827,329.[171]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Lennon–McCartney, except where noted

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Come Together" | Lennon | 4:19 |

| 2. | "Something" (George Harrison) | Harrison | 3:02 |

| 3. | "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" | McCartney | 3:27 |

| 4. | "Oh! Darling" | McCartney | 3:27 |

| 5. | "Octopus's Garden" (Richard Starkey) | Starr | 2:51 |

| 6. | "I Want You (She's So Heavy)" | Lennon | 7:47 |

| Total length: | 24:53 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Here Comes the Sun" (Harrison) | Harrison | 3:05 |

| 2. | "Because" | Lennon, McCartney and Harrison | 2:45 |

| 3. | "You Never Give Me Your Money" | McCartney | 4:03 |

| 4. | "Sun King" | Lennon, with McCartney and Harrison | 2:26 |

| 5. | "Mean Mr. Mustard" | Lennon | 1:06 |

| 6. | "Polythene Pam" | Lennon | 1:13 |

| 7. | "She Came In Through the Bathroom Window" | McCartney | 1:58 |

| 8. | "Golden Slumbers" | McCartney | 1:31 |

| 9. | "Carry That Weight" | McCartney, with Lennon, Harrison and Starr | 1:36 |

| 10. | "The End" | McCartney | 2:05 |

| 11. | "Her Majesty" (hidden track) | McCartney | 0:23 |

| Total length: | 22:10 | ||

Notes

- "Her Majesty" appears as a hidden track after "The End" and 14 seconds of silence. Later releases of the album included the song on the track listing, except some vinyl editions.

- Some cassette tape versions in the UK and US had "Come Together" and "Here Comes the Sun" swapped to even out the playing time of each side.[172]

Personnel

According to Mark Lewisohn,[173] Ian MacDonald,[174] Barry Miles,[175] Kevin Howlett,[176] and Geoff Emerick.[177]

|

The Beatles

Additional musicians

|

Production

|

Charts

|

Original release

1987 reissue

|

2009 reissue

|

2019 reissue

|

| Chart (1969) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums Chart[179] | 3 |

| UK Albums Chart[232] | 1 |

| Chart (1970) | Position |

| Australian Albums Chart[179] | 7 |

| UK Albums Chart[233] | 7 |

| US Billboard Pop Albums[234] | 4 |

| Chart (2017) | Position |

| US Billboard 200[235] | 138 |

| US Top Rock Albums (Billboard)[236] | 27 |

| Chart (2018) | Position |

| US Billboard 200[237] | 163 |

| US Top Rock Albums (Billboard)[238] | 26 |

| Chart (2019) | Position |

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[239] | 40 |

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[240] | 72 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[241] | 41 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Wallonia)[242] | 90 |

| Danish Albums (Hitlisten)[243] | 68 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[244] | 47 |

| Mexican Albums (AMPROFON)[245] | 85 |

| Spanish Albums (PROMUSICAE)[246] | 73 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[247] | 94 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[248] | 38 |

| US Billboard 200[249] | 57 |

| US Top Rock Albums (Billboard)[250] | 7 |

| Chart (2020) | Position |

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[251] | 95 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[252] | 145 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[253] | 90 |

| Spanish Albums (PROMUSICAE)[254] | 91 |

| US Billboard 200[255] | 66 |

| US Top Rock Albums (Billboard)[256] | 5 |

| Chart (2021) | Position |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[257] | 128 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[258] | 68 |

| US Billboard 200[259] | 96 |

| US Top Rock Albums (Billboard)[260] | 11 |

| Chart (2022) | Position |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[261] | 192 |

| US Billboard 200[262] | 103 |

| US Top Rock Albums (Billboard)[263] | 16 |

| Chart (1960s) | Position |

|---|---|

| UK Albums Chart[232] | 4 |

| Chart (1970s) | Position |

| Japanese Albums Chart[105] | 22 |

Certifications and sales

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[264] | Diamond | 506,916[265] |

| Australia (ARIA)[266] | 3× Platinum | 210,000^ |

| Belgium (BEA)[267] | Platinum | 50,000‡ |

| Brazil | — | 390,000[268] |

| Canada (Music Canada)[269] | Diamond | 1,000,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[270] | 4× Platinum | 80,000‡ |

| France (SNEP)[271] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[272] | Platinum | 500,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[273] sales since 2009 |

2× Platinum | 100,000‡ |

| Japan | — | 655,000[105] |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[274] | 5× Platinum | 75,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[275] | 8× Platinum | 2,400,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[276] | 12× Platinum | 12,000,000^ |

| Summaries | ||

| Worldwide Worldwide sales in 2019 |

— | 800,000[277][278] |

| Worldwide Worldwide sales up to 2014 |

— | 31,000,000[161] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

† BPI certification awarded only for sales since 1994.[279]

Release history

| Country | Date | Label | Format | Catalogue number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 26 September 1969 | Apple (Parlophone) | LP | PCS 7088 |

| United States | 1 October 1969 | Apple, Capitol | LP | SO 383 |

| Japan | 21 May 1983 | Toshiba-EMI | Compact Disc | CP35-3016 |

| Worldwide reissue | 10 October 1987 | Apple, Parlophone, EMI | CD | CDP 7 46446 2 |

| Japan | 11 March 1998 | Toshiba-EMI | CD | TOCP 51122 |

| Japan | 21 January 2004 | Toshiba-EMI | Remastered LP | TOJP 60142 |

| Worldwide reissue | 9 September 2009 | Apple, Parlophone, EMI | Remastered CD | 0946 3 82468 24 |

| Worldwide reissue | 27 September 2019 | Apple, Universal Music Group International | Remixed LP | 7791512 |

| LP+ (picture disc) | 804888 | |||

| 3×LP | 800744 | |||

| CD | 800743 | |||

| 2×CD | 7791507 | |||

| 3×CD+Blu-ray box set | 7792112[280] |

See also

Notes

- ^ In the 1960s, UK record industry protocol was that singles did not normally appear on albums.[37]

- ^ In the version released on Anthology 3, Lennon can be heard singing the lead on an ad-libbed verse regarding the news that Yoko Ono's divorce from her previous husband Anthony Cox had been finalised.[43]

- ^ At 8:22, "Revolution 9" is the longest track to appear on a Beatles album.

- ^ A working title of the album was Everest, after a brand of cigarettes favoured by Emerick, but the band were reluctant to travel to the Himalayas for a photo session.[11]

- ^ In 1986, the car was sold at auction for £2,530[89] and in 2001 was on display in a museum in Germany.[90]

- ^ Anderson added: "[The Beatles] showed us that you can do anything ... That if you can do it with love, heart and honesty, it'll work."[151]

References

Citations

- ^ Matthews, Rex D. (2007). Timetables of History for Students of Methodism. Abingdon Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1426764592.

- ^ a b c d MacDonald 1997, p. 300.

- ^ a b c MacDonald 1997, p. 322.

- ^ Perone, James E. The Album: A Guide to Pop Music's Most Provocative, Influential, and Important Creations. p. 215.

- ^ Buckley 2003, p. 76.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 552.

- ^ a b c "100 Greatest Beatles Songs – Abbey Road Medley". Rolling Stone. 19 September 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 302, 304.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 308, 310.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d e f MacDonald 1997, p. 321.

- ^ a b MacFarlane 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 551.

- ^ Stark 2005, p. 261.

- ^ Wenner & Lennon 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Inglis, Sam (October 2009). "Remastering The Beatles". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 245.

- ^ Lawrence, Alistair; Martin, George (2012). Abbey Road: The Best Studio in the World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-4088-3241-7. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Gottlieb 2010, p. 104.

- ^ Gottlieb 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Womack 2019, p. 235.

- ^ "Alan Parsons: 'Working with the Beatles Was An Amazing Experience". Ultimate Guitar. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "Producer Profile : John Kurlander". studioexpresso. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 314.

- ^ Wardlaw, Matt (10 May 2011). "The Beatles 'Come Together' Lyrics Uncovered". Classic Rock Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ a b Gould 2008, p. 575.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 315.

- ^ Wenner & Lennon 2001, p. 90.

- ^ Wallgren 1982, p. 57.

- ^ Martin, George. Love (Media notes). The Beatles. Parlophone. 0946-3-79808-2-8.

- ^ Gould 2008, p. 576.

- ^ a b c Everett 1999, p. 249.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Abowitz, Richard (13 December 2006). "Sinatra, Elvis and The Beatles". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2006.

- ^ "George Harrison: The Quiet Beatle". BBC News. 30 November 2001. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 412.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 201.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (24 March 2008). "Neil Aspinall, Beatles Aide, Dies at 66". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 313.

- ^ a b Emerick & Massey 2006, p. 281.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 1988, p. 179.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 307.

- ^ John Lennon. Disc 2, track 9. Anthology 3 (CD). Apple Records. Event occurs at 3:28. 7423-8-34451-2-7.

Just heard that Yoko's divorce has gone through

- ^ Beatles 2000, p. 339.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 203.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Spizer 2005, pp. 293, 297, 303.

- ^ Wenner & Lennon 2001, p. 83.

- ^ Maginnis, Tom. "I Want You (She's So Heavy) song review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 301.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 1988, p. 178.

- ^ Gaar, Gillian (2013). 100 Things Beatles Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die. Triumph Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-62368-202-6.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 312.

- ^ "Desert Island Discs – Beatles – Here Comes The Sun". BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Chilton, Martin (18 July 2013). "20 songs for a heatwave". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014.

- ^ a b "'Here Comes the Sun' Is No. 1 Beatles Song After a Week of Sales on ITunes". Bloomberg. 24 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (28 March 2012). "New George Harrison guitar solo uncovered". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 191.

- ^ "Why the Beatles Reordered the 'Abbey Road' Medley (by Nick DeRiso)". ultimateclassicrock.com. 26 September 2019. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ DeRiso, Nick (26 September 2019). "Why the Beatles Reordered the 'Abbey Road' Medley". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ "Abbey Road". beatlesbible.com. September 2019. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ Lewisohn 1988, p. 183.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 556.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 310.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 247.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 318, 319.

- ^ Turner 1994, p. 198.

- ^ McCartney: Songwriter ISBN 0-491-03325-7 p. 93

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 311–312.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 317.

- ^ "Tomorrow Never Knows". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Marvin, Elizabeth West; Hermann, Richard (2002). Marvin, Elizabeth West; Hermann, Richard (eds.). Concert Music, Rock, and Jazz Since 1945: Essays and Analytical Studies. University of Rochester Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-58046-096-5. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1997, p. 311.

- ^ Abbey Road (Media notes). Apple Records. 1969. PCS 7088.

- ^ Abbey Road (CD remaster) (Media notes). Apple Records. 1987. CDP 7 46446 2.

- ^ Abbey Road (Media notes). Apple Records. 2009. 94638-24682. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

- ^ Abbey Road (Media notes). Apple Records. 2012. EAS-80560. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 302, 305.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 305, 447.

- ^ Lewisohn 1988, p. 182.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 318.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (16 February 2013). "Top 10 Beatles Bootleg Albums". Classic Rock Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Sulpy, Doug; Chen, Ed (1990–1994). "A beginner's guide to Beatles bootlegs". rec.music.beatles. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Pollard, Lawrence (7 August 2009). "Revisiting Abbey Road 40 years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, p. 559.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Etherington-Smith, Meredith (18 August 1992). "Obituary: Tommy Nutter". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ McNichol, Tom (9 August 1989). "Eyewitness: The long and winding road to an icon". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012.

- ^ Rubin, Judith (16 March 2001). "Online Exclusive: Volkswagen Autostadt". Live Design. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013.

- ^ DeYoung, Bill (7 June 2016). "Paul Cole, man on Beatles' 'Abbey Road' cover, dies". TCPalm. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015.

- ^ Urish 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Rodriguez 2010, pp. 1, 73.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 561.

- ^ Womack 2009, p. 290.

- ^ Womack 2009, p. 286.

- ^ Urish 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 574.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, p. 271.

- ^ "1969 The Number One Albums". Official Chart Company. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "1970 The Number One Albums". Official Chart Company. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "The Beatles: every album and single, with its chart position". The Guardian. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 216.

- ^ "NARM Awards". Billboard. 6 March 1971. p. N27.

- ^ a b c d e Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005. Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 978-4-87131-077-2.

- ^ Gould 2008, p. 593.

- ^ a b c d e Stark 2005, p. 262.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (2003). "Road to Nowhere". In Mojo: The Beatles' Final Years Special Edition. London: Emap. p. 112.

- ^ Cohn, Nik (5 October 1969). "The Beatles: For 15 Minutes, Tremendous". The New York Times. Hi Fi and Recordings section, p. HF13. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Goldman, Albert (21 November 1969). "Beatles: Nostalgia, Irony". Life. Chicago. p. 22. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ In Brief, High-Fidelity, January 1970, p. 142.

- ^ Welch, Chris (27 September 1969). "The Beatles: Abbey Road (Apple)". Melody Maker. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Mendelsohn, John (15 November 1969). "Abbey Road". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Best of the Month: Stereo Review's Selection of Recordings of Special Merit, Stereo Review, January 1970.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (December 1969). "In Memory of the Dave Clark Five". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ a b Erlweine, Stephen Thomas; Unterberger, Richie. "Abbey Road – The Beatles". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (8 September 2009). "Chuck Klosterman Repeats The Beatles". The A.V. Club. Chicago. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Album Review: The Beatles - Abbey Road [Remastered]". 26 September 2009. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014.

- ^ a b McCormick, Neil (8 September 2009). "The Beatles – Abbey Road, review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012.

- ^ Larkin 2006, p. 489.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ^ a b Kemp, Mark (8 September 2009). "The Beatles: The Long and Winding Repertoire". Paste. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (10 September 2009). "The Beatles: Abbey Road". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "The Beatles | Album Guide | Rolling Stone Music". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014.

- ^ N/A, N/A (27 February 2012). "Abbey Road". AnyDecentMusic?. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Roberts 2011, p. 80.

- ^ Pensiero, Nicole (23 March 2004). "The Beatles: Abbey Road". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Celebrating 40 Years of The Beatles' "Abbey Road"". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "2001 VH1 Cable Music Channel All Time Album Top 100". VH1. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest British Albums Ever". Q. Archived from the original on 26 November 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 36. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ "The All-Time 100 Albums". Time. 2 November 2006. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: The Beatles, 'Abbey Road'". Rolling Stone. 31 May 2009. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (7 February 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (Revised and Updated ed.). Universe. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

- ^ Landau, Joel (4 September 2014). "SEE IT: Live feed gives continuous view of Abbey Road crossing made famous by the Beatles". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Beatles' Abbey Road zebra crossing given listed status". BBC News. 22 December 2010. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 273.

- ^ Scott, Jane (24 October 1969). "Paul's death 'exaggerated'". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 127–28.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 333.

- ^ Womack 2019, p. 236.

- ^ Cooney, Caroline (6 April 2012). "Every Parody Tells A Story". grammy.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Rodriguez 2010, p. 339.

- ^ "The Abbey Road EP". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Beatles Abbey Road cigarette airbrushed". BBC News. 21 January 2003. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ "Beatles' Abbey Road cover in Calcutta traffic campaign". BBC News. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "The Other Side of Abbey Road". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "McLemore Avenue". AllMusic. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ a b Anderson, Jon (October 2014). "'They were the leaders of everything, and everybody else slowly followed': Jon Anderson on why the Beatles were the original progressive rock band". Classic Rock. p. 37.

- ^ "In My Life – George Martin". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 14 July 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Jam band draws thousands". The Victoria Advocate. 4 May 2001. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Transatlantic – Live in Europe". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Watch Page McConnell Team Up With Tenacious D on Flash, Wonderboy and Beatles Abbey Road Medley". Glide Magazine. 11 October 2012. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Furthur Celebrates Phil's Birthday w/ Abbey Road B-Side Medley and Cupcakes". Glide Magazine. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Dove, Ian (6 June 1970). "Beatlemania Returns As 'Let It Be' Clicks". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. 1. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (31 January 2014). "Beatles + Sullivan = Revolution: Why Beatlemania could never happen today". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Grein, Paul (19 February 2014). "Chart Watch: Taylor Swift Is 4 For 4 (Million)". Yahoo Music. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "How Many Records did the Beatles actually sell?". Deconstructing Pop Culture by David Kronemyer. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Back in the Day: Abbey Road hits the shelves". Euronews. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Glynn, Paul (4 October 2019). "The Beatles' Abbey Road returns to number one 50 years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 410.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 411.

- ^ "Abbey Road (1978 LP)". AllMusic. 17 February 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

- ^ "Abbey Road – releases". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ "Abbey Road [2009 Remaster]". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum News". RIAA. February 2001. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "Abbey Road (Collector's Crate Black)". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Knopper, Steve (12 November 2012). "Inside the Beatles' vinyl album remasters". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Alan Jones (7 October 2019). "Golden oldie: Abbey Road returns to the summit 50 years on" (PDF). Music Week. p. 77. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Abbey Road. EMI. TC-PCS 7088. Archived from the original (cassette) on 13 November 2013.

- ^ Lewisohn 1988.

- ^ MacDonald 1997, pp. 300–321.

- ^ Miles 1997.

- ^ Howlett, Kevin (2019). Abbey Road (50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Version) (book). The Beatles. Apple Records.

- ^ Bosso, Joe. ""For the first time, John and Paul knew that George had risen to their level" – Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick track-by-track interview on Abbey Road". musicradar. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 365.

- ^ a b c Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 978-0-646-11917-5.

- ^ "RPM – Library and Archives Canada". RPM. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "dutchcharts.nl The Beatles – Abbey Road". Hung Medien, dutchcharts.nl (in Dutch). MegaCharts. Archived from the original (ASP) on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-31-2503-3.

- ^ "Hits of the World" (PDF). Billboard. 31 January 1970. p. 70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "norwegiancharts.com The Beatles – Abbey Road". Archived from the original (ASP) on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Swedish Charts 1969–1972" (PDF) (in Swedish). Hitsallertijden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 978-84-8048-639-2.

- ^ a b "The Beatles – Full official Chart History". Official Charts. 17 October 1962. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "The Beatles – Chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "Album Search: The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in German). Media Control. Archived from the original (ASP) on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "The Official Charts Company – The Beatles – Abbey Road (1987 version)". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "australian-charts.com The Beatles – Abbey Road". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original (ASP) on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "austriancharts.at The Beatles – Abbey Road". Hung Medien (in German). Archived from the original (ASP) on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "ultratop.be The Beatles – Abbey Road" (ASP). Hung Medien (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "ultratop.be The Beatles – Abbey Road" (ASP). Hung Medien (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "danishcharts.dk The Beatles – Abbey Road" (ASP). danishcharts.dk. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "finnishcharts.com The Beatles – Abbey Road". Hung Medien. Archived from the original (ASP) on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "musicline.de chartverfolgung". hitparade.ch. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "italiancharts.com The Beatles – Abbey Road". Hung Medien. Recording Industry Association of New Zealand. Archived from the original (ASP) on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "All of the Beatles' "Remastered" Albums Enter the Top 100: Grossing 2,310 Million Yen in One Week". oricon.co.jp (in Japanese). Oricon Style. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "mexicancharts.com The Beatles – Abbey Road". mexicancharts.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "portuguesecharts.com The Beatles – Abbey Road". Hung Medien. Archived from the original (ASP) on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "The Beatles – Abbey Road". spanishcharts.com. Hung Medien. Archived from the original (ASP) on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "swedishcharts.com The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in Swedish). Archived from the original (ASP) on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "The Beatles – Abbey Road – hitparade.ch". Hung Medien (in German). Swiss Music Charts. Archived from the original (ASP) on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "charts.nz The Beatles – Abbey Road" (ASP). Hung Medien. Recording Industry Association of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith. "Beatles and Jay-Z Dominate Charts". Billboard.biz. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "ARIA Australian Top 50 Albums". Australian Recording Industry Association. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "The Beatles Chart In A Post Malone World". FYIMusicNews. 6 October 2019. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Czech Albums – Top 100". ČNS IFPI. Note: On the chart page, select 40.Týden 2019 on the field besides the words "CZ – ALBUMS – TOP 100" to retrieve the correct chart. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Hitlisten.NU – Album Top-40 Uge 39, 2019". Hitlisten. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Beatles: Abbey Road" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "The Beatles Chart History (Greece Albums)". Billboard. 10 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2019. 43. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "IRMA – Irish Charts". Irish Recorded Music Association. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Album – Classifica settimanale WK 40 (dal 27.09.2019 al 03.10.2019)" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Top Album – Semanal (del 27 de septiembre al 3 de octubre de 2019)" (in Spanish). Asociación Mexicana de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "NZ Top 40 Albums Chart". Recorded Music NZ. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "VG-lista – Topp 40 Album uke 40, 2019". VG-lista. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – The Beatles – Abbey Road". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Top 100 Albumes – Semana 40: del 27.9.2019 al 3.10.2019" (in Spanish). Productores de Música de España. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "Veckolista Album, vecka 40". Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – The Beatles – Abbey Road". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (6 October 2019). "DaBaby Earns First No. 1 Album on Billboard 200 Chart With 'Kirk'". Billboard. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "The Beatles Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The Official UK Charts Company : ALBUM CHART HISTORY". Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ "1970s Albums Chart Archive". everyhit.com. The Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "Billboard.BIZ – TOP POP ALBUMS OF 1970". Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2017". Billboard. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2017". Billboard. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2018". Billboard. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2018". Billboard. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "ARIA End of Year Albums Chart 2019". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 2019". austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2019". Ultratop. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 2019". Ultratop. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Album Top-100 2019" (in Danish). Hitlisten. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 2019". dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 México - Los más vendidos 2019" (in Spanish). Asociación Mexicana de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums Annual 2019". El portal de Música. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Årslista Album, 2019". Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (1 January 2020). "The Official Top 40 biggest albums of 2019". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2019". Billboard. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2019". Billboard. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 2020". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2020". Ultratop. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 2020" (in Dutch). MegaCharts. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums Annual 2020". El portal de Música. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2020". Billboard. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2020". Billboard. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2021". Ultratop. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 2021". dutchcharts.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2021". Billboard. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2021". Billboard. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2022" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2022". Billboard. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2022". Billboard. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Premio Diamante: Los premiados" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 18 March 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ Franco, Adriana (27 October 1999). "Nuevo galardón en la industria del disco". La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2009 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 2022". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "O sargento Pimenta faz 20 anos". Jornal do Brasil (in Portuguese). 1 June 1987. p. 37 – via National Library of Brazil.

Sgt. pepper's que toca em cinco paginas desta edicao, e o terceiro mais vendido (290 mil). Perde Abbey Road (390 mil) e para Help (320 mil)

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – The Beatles – Abbey Road". Music Canada. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Danish album certifications – The Beatles – Abbey Road". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "French album certifications – The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in French). InfoDisc. Select THE BEATLES and click OK.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (The Beatles; 'Abbey Road')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – The Beatles – Abbey Road" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Latest Gold / Platinum Albums". Radioscope. 17 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- ^ "British album certifications – The Beatles – Abbey Road". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "American album certifications – The Beatles – Abbey Road". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Arashi Best-Of Tops Taylor Swift for IFPI's Best-Selling Album of 2019". Billboard. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ "Best Sellers and Global Artist of the Year — IFPI — Representing the recording industry worldwide". IFPI.org. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Beatles albums finally go platinum". British Phonographic Industry. BBC News. 2 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "The Beatles - Abbey Road – 50th Anniversary Edition - CDx4". Rough Trade. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

Bibliography