History of Karachi: Difference between revisions

Sir Calculus (talk | contribs) →Post Islamic era (8th century AD – 19th century): naming in consistency with other sections |

Sir Calculus (talk | contribs) →Kharak Bander: ref & addition, made it concise |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

In AD 711, [[Muhammad bin Qasim]], a commander of the [[Umayyad dynasty]], conquered [[Sindh]] and [[Indus Valley]], bringing South Asian societies into contact with Islam, succeeding partly because [[Raja Dahir]] was a Hindu king that ruled over a Buddhist majority and that [[Chach of Alor]] and his kin were regarded as usurpers of the earlier Buddhist [[Rai dynasty]]<ref name="Gier">{{cite conference|author=Nicholas F. Gier |title=FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES |conference=Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006 |url=http://www.class.uidaho.edu/ngier/mm.htm |access-date=11 December 2006}}</ref><ref name=Naik>{{cite book|last=Naik|first=C.D. |title=Buddhism and Dalits: Social Philosophy and Traditions|year=2010 |publisher=Kalpaz Publications|location=Delhi|isbn=978-81-7835-792-8|page=32}}</ref> this view is questioned by those who note the diffuse and blurred nature of Hindu and Buddhist practices in the region,<ref>P. 151 ''Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World'' By André Wink</ref> especially that of a royalty to be patrons of both and those who believe that Chach himself may have been a Buddhist.<ref>P. 164 ''Notes on the religious, moral, and political state of India before the Mahomedan invasion, chiefly founded on the travels of the Chinese Buddhist priest Fai Han in India, A.D. 399, and on the commentaries of Messrs. Remusat, Klaproth, Burnouf, and Landresse, Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Sykes'' by Sykes, Colonel;</ref><ref>P. 505 ''[[The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians]]'' by Henry Miers Elliot, John Dowson</ref> The forces of Muhammad bin Qasim defeated Raja Dahir in alliance with the [[Jat people|Jats]] and other regional governors. |

In AD 711, [[Muhammad bin Qasim]], a commander of the [[Umayyad dynasty]], conquered [[Sindh]] and [[Indus Valley]], bringing South Asian societies into contact with Islam, succeeding partly because [[Raja Dahir]] was a Hindu king that ruled over a Buddhist majority and that [[Chach of Alor]] and his kin were regarded as usurpers of the earlier Buddhist [[Rai dynasty]]<ref name="Gier">{{cite conference|author=Nicholas F. Gier |title=FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES |conference=Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006 |url=http://www.class.uidaho.edu/ngier/mm.htm |access-date=11 December 2006}}</ref><ref name=Naik>{{cite book|last=Naik|first=C.D. |title=Buddhism and Dalits: Social Philosophy and Traditions|year=2010 |publisher=Kalpaz Publications|location=Delhi|isbn=978-81-7835-792-8|page=32}}</ref> this view is questioned by those who note the diffuse and blurred nature of Hindu and Buddhist practices in the region,<ref>P. 151 ''Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World'' By André Wink</ref> especially that of a royalty to be patrons of both and those who believe that Chach himself may have been a Buddhist.<ref>P. 164 ''Notes on the religious, moral, and political state of India before the Mahomedan invasion, chiefly founded on the travels of the Chinese Buddhist priest Fai Han in India, A.D. 399, and on the commentaries of Messrs. Remusat, Klaproth, Burnouf, and Landresse, Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Sykes'' by Sykes, Colonel;</ref><ref>P. 505 ''[[The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians]]'' by Henry Miers Elliot, John Dowson</ref> The forces of Muhammad bin Qasim defeated Raja Dahir in alliance with the [[Jat people|Jats]] and other regional governors. |

||

=== |

=== Kharak Bander === |

||

In |

In 1729, immigrants from the [[siltation|silting-up]] port of Kharak relocated to found Karachi near the [[Hub River]] mouth. Initially, Karachi was a modest settlement, but its trade grew as other ports like Shahbandar and Keti Bandar also silted up.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Eggermont |first1=Pierre Herman Leonard |title=Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia |date=1975 |publisher=Peeters Publishers |location=Leuven |isbn=9789061860372 |page=55}}</ref><ref>[http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu-projects/Global_Report/pdfs/Karachi.pdf The case of Karachi, Pakistan]</ref> |

||

=== Kalhora dynasty === |

=== Kalhora dynasty === |

||

Revision as of 13:36, 3 November 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Karachi |

|---|

|

| Prehistoric period |

| Ancient period |

| Classical period |

| Islamic period |

| Local dynasties |

| British period |

| Independent Pakistan |

The area of Karachi (Urdu: کراچی, Sindhi: ڪراچي) in Sindh, Pakistan has a natural harbor and has been used as fishing port by local fisherman belonging to Sindhi tribes since prehistory. Archaeological excavations have uncovered a period going back to Indus valley civilisation which shows the importance of the port since the Bronze Age. The port city of Banbhore was established before the Christian era which served as an important trade hub in the region, the port was recorded by various names by the Greeks such as Krokola, Morontobara port, and Barbarikon, a sea port of the Indo-Greek Bactrian kingdom and Ramya according to some Greek texts.[1] The Arabs knew it as the port of Debal, from where Muhammad bin Qasim led his conquering force into Sindh (the western corner of South Asia) in AD 712. Lahari Bandar or Lari Bandar succeeded Debal as a major port of the Indus; it was located close to Banbhore, in modern Karachi. The first modern port city near Manora Island (now Manora Peninsula) was established during British colonial Raj in the late 19th century.

Names

The ancient names of Karachi included: Krokola, Barbarikon, Nawa Nar, Rambagh, Kurruck, Karak Bander, Auranga Bandar, Minnagara, Kalachi, Morontobara, Kalachi-jo-Goth, Banbhore, Debal, Barbarice, and Kurrachee.

Early history

Pre history

The Late Paleolithic and Mesolithic sites found by Karachi University team on the Mulri Hills, in front of Karachi University Campus, constitute one of the most important archaeological discoveries made in Sindh during the last fifty years. The last hunter-gatherers, who left abundant traces of their passage, repeatedly inhabited the Hills. Some twenty different spots of flint tools were discovered during the surface surveys.

Indus Valley Civilisation

Ahladino and Pir Shah Jurio are the archaeological sites from the Indus Valley civilisation periods situated in Karachi district. Floor tiles of a house have been discovered at this site of Ahladino.

Greeks Visitors

The Greeks recorded the place by many names: Krokola, the place where Alexander camped to prepare a fleet for Babylon after his campaign in the Indus Valley; Morontobara, from whence Alexander's admiral Nearchus set sail; and Barbarikon, a port of the Bactrian kingdom.

Debal and Bhanbhore

Debal and Bhanbhore were the ancient port cities established near present-day modern city of Karachi. It dates back to the Scytho-Parthian era and was later controlled by Hindu Buddhist kingdoms before falling into Arab possession in the 8th century CE. In the 13th century it was abandoned Remains of one of the earliest known mosques in the region dating back to 727 AD are still preserved in the city. Strabo mentions export of rice (from near present-day Karachi and Gulf of Cambay) to Arabia.[2]

According to Biladuri, A large minaret of a temple existed in Debal whose upper portion was knocked down by Ambissa Ibn Ishak and converted into prison. and at the same time began to repair the ruined town with the stones of minaret.[3]

Post Islamic era (8th century AD – 19th century)

Umayyad dynasty

In AD 711, Muhammad bin Qasim, a commander of the Umayyad dynasty, conquered Sindh and Indus Valley, bringing South Asian societies into contact with Islam, succeeding partly because Raja Dahir was a Hindu king that ruled over a Buddhist majority and that Chach of Alor and his kin were regarded as usurpers of the earlier Buddhist Rai dynasty[4][5] this view is questioned by those who note the diffuse and blurred nature of Hindu and Buddhist practices in the region,[6] especially that of a royalty to be patrons of both and those who believe that Chach himself may have been a Buddhist.[7][8] The forces of Muhammad bin Qasim defeated Raja Dahir in alliance with the Jats and other regional governors.

Kharak Bander

In 1729, immigrants from the silting-up port of Kharak relocated to found Karachi near the Hub River mouth. Initially, Karachi was a modest settlement, but its trade grew as other ports like Shahbandar and Keti Bandar also silted up.[9][10]

Kalhora dynasty

The name Karachee was used for the first time in a Dutch document from 1742, in which a merchant ship de Ridderkerk is shipwrecked near the original settlement.[11][12] The city continued to be ruled by the Talpur Amir's of Sindh until it was occupied by Bombay Army under the command of John Keane on 2 February 1839.[13]

Colonial period (1839–1947)

Company rule

After sending a couple of exploratory missions to the area, the British East India Company conquered the town on February 3, 1839. The town was later annexed to the British Indian Empire when Sindh was conquered by Charles James Napier in the Battle of Miani on February 17, 1843. Karachi was made the capital of Sindh in the 1840s. On Napier's departure it was added along with the rest of Sindh to the Bombay Presidency, a move that caused considerable resentment among the native Sindhis. The British realised the importance of the city as a military cantonment and as a port for exporting the produce of the Indus River basin, and rapidly developed its harbour for shipping. The foundations of a city municipal government were laid down and infrastructure development was undertaken. New businesses started opening up and the population of the town began rising rapidly.

The arrival of troops of the Kumpany Bahadur in 1839 spawned the foundation of the new section, the military cantonment. The cantonment formed the basis of the 'white' city where the Indians were not allowed free access. The 'white' town was modeled after English industrial parent-cities where work and residential spaces were separated, as were residential from recreational places.

Karachi was divided into two major poles. The 'black' town in the northwest, now enlarged to accommodate the burgeoning Indian mercantile population, comprised the Old Town, Napier Market and Bunder, while the 'white' town in the southeast comprised the Staff lines, Frere Hall, Masonic lodge, Sindh Club, Governor House and the Collectors Kutchery [Law Court] /kəˈtʃɛri/[citation needed] located in the Civil Lines Quarter. Saddar bazaar area and Empress Market were used by the 'white' population, while the Serai Quarter served the needs of the native population.

The village was later annexed to the British Indian Empire when the Sindh was conquered by Charles Napier in 1843. The capital of Sindh was shifted from Hyderabad to Karachi in the 1840s. This led to a turning point in the city's history. In 1847, on Napier's departure the entire Sindh was added to the Bombay Presidency. The post of the governor was abolished and that of the Chief Commissioner in Sindh established.

The British realized its importance as a military cantonment and a port for the produce of the Indus basin, and rapidly developed its harbor for shipping. The foundation of a city municipal committee was laid down by the Commissioner in Sinde, Bartle Frere and infrastructure development was undertaken. Consequently, new businesses started opening up and the population of the town started rising rapidly. Karachi quickly turned into a city, making true the famous quote by Napier who is known to have said: Would that I could come again to see you in your grandeur!

In 1857, the Indian Mutiny broke out, and the 21st Native Infantry stationed in Karachi declared allegiance to rebels, joining their cause on 10 September 1857. Nevertheless, the British were able to quickly reassert control over Karachi and defeat the uprising. Karachi was known as Khurachee Scinde (i.e. Karachi, Sindh) during the early British colonial rule.

In 1864, the first telegraphic message was sent from India to England when a direct telegraph connection was laid between Karachi and London.[14] In 1878, the city was connected to the rest of British India by rail. Public building projects such as Frere Hall (1865) and the Empress Market (1890) were undertaken. In 1876, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, was born in the city, which by now had become a bustling city with mosques, temples, churches, courthouses, markets, paved streets and a magnificent harbour. By 1899, Karachi had become the largest wheat exporting port in the east.[15] The population of the city was about 105,000 inhabitants by the end of the 19th century, with a cosmopolitan mix of Muslims, Hindus, Europeans, Jews, Parsis, Iranians, Lebanese, and Goans. The city faced a huge cholera epidemic in 1899.[16] By around the start of the 20th century, the city faced street congestion, which led to South Asia's first tramway system being laid down in 1900.

The city remained a small fishing village until the British seized control of the offshore and strategically located at Manora Island. Thereafter, authorities of the British Raj embarked on a large-scale modernisation of the city in the 19th century with the intention of establishing a major and modern port which could serve as a gateway to Punjab, the western parts of British Raj, and Afghanistan. The city was predominantly Muslim with Sindhi and Baloch ethnic groups. Britain's competition with imperial Russia during the Great Game also heightened the need for a modern port near Central Asia, and so Karachi prospered as a major centre of commerce and industry during the Raj, attracting communities of: Africans, Arabs, Armenians, Catholics from Goa, Jews, Lebanese, Malays, Konkani people from Maharashtra, Kuchhi from Kuchh, Gujarat in India, and Zoroastrians (also known as Parsees)—in addition to the large number of British businessmen and colonial administrators who established the city's poshest locales, such as Clifton. This mass migration changed the religious and cultural mosaic of Karachi.

British colonialists embarked on a number of public works of sanitation and transportation, such as gravel paved streets, proper drains, street sweepers, and a network of trams and horse-drawn trolleys. Colonial administrators also set up military camps, a European inhabited quarter, and organised marketplaces, of which the Empress Market is most notable. The city's wealthy elite also endowed the city with a large number of grand edifices, such as the elaborately decorated buildings that house social clubs, known as 'Gymkhanas.' Wealthy businessmen also funded the construction of the Jehangir Kothari Parade (a large seaside promenade) and the Frere Hall, in addition to the cinemas, and gambling parlours which dotted the city.

By 1914, Karachi had become the largest grain exporting port of the British Empire. In 1924, an aerodrome was built and Karachi became the main airport of entry into British Raj. An airship mast was also built in Karachi in 1927 as part of the Imperial Airship Communications scheme, which was later abandoned. In 1936, Sindh was separated from the Bombay Presidency and Karachi was made again the capital of the Sindh. In 1947, when Pakistan achieved independence, Karachi had become a bustling metropolitan city with beautiful classical and colonial European styled buildings lining the city's thoroughfares.

As the movement for independence almost reached its conclusion, the city suffered widespread outbreaks of communal violence between Muslims and Hindus, who were often targeted by the incoming Muslim refugees. In response to the perceived threat of Hindu domination, self-preservation of identity, the province of Sindh became the first province of British India to pass the Pakistan Resolution, in favour of the creation of the Pakistani state. The Muslim population supported Muslim League and Pakistan Movement. After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, Hindus and Sikhs migrated to India and this led to the decline of Karachi, as Hindus controlled the business in Karachi, while the Muslim refugees from India settled down in Karachi. While many poor low caste Hindus, Christians, and wealthy Zoroastrians (Parsees) remained in the city, Karachi's Sindhi Hindu migrated to India and was replaced by Muslim refugees who, in turn, had been uprooted from regions belonging to India.

Post-Independence (1947 CE – present)

Pakistan's capital (1947–1958)

Karachi was chosen as the capital city of Pakistan. After the independence of Pakistan, the city population increased dramatically when hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees from India fleeing from anti-Muslim pogroms and from other parts of South Asia came to settle in Karachi.[17] As a consequence, the demographics of the city also changed drastically. The Government of Pakistan through Public Works Department bought land to settle the Muslim refugees.[18] However, it still maintained a great cultural diversity as its new inhabitants arrived from the different parts of the South Asia. In 1959, the capital of Pakistan was shifted from Karachi to Islamabad. Karachi remained a federal territory and became the capital of Sindh in 1970 by General Yahya Khan.

Picture gallery

-

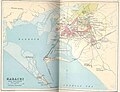

A map of Karachi from 1889

-

The Empress Market, 1890

-

A map of Karachi from 1893

-

View of the dense old native town by the end of the 19th century

-

View of the Bunder Road (now M. A. Jinnah Rd.), 1900

-

Bunder Road

-

Farewell arch erected by the Karachi Port for the Royal visit of Prince of Wales, later King George V, 1906

-

British family at Elphinstone St., 1914

See also

- Demographic history of Karachi

- Abdullah Shah Ghazi

- Bhambore

- Culture of Karachi

- Debal

- Demographics of Karachi

- Economy of Karachi

- Education in Karachi

- History of Pakistan

- History of Sindh

- Karachi

- Kolachi jo Goth

- Kolachi

- Krokola

- Kulachi (tribe)

- Mai Kolachi

- Morontobara

- Muhammad bin Qasim

- Politics of Karachi

- Timeline of Karachi history

- Timeline of Karachi

References

- ^ "Infiltration by the gods". Archived from the original on 2017-07-07. Retrieved 2013-01-14.

- ^ Reddy, Anjana. "Archaeology of Indo-Gulf Relations in the Early Historic Period: The Ceramic Evidence". In H.P Ray (ed.). Bridging the Gulf: Maritime Cultural Heritage of the Western Indian Ocean. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers.

- ^ SARAO, K. T. S. (2017). "Buddhist-Muslim Encounter in Sind During the Eighth Century". Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. 77: 75–94. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 26609161.

- ^ Nicholas F. Gier. FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES. Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Naik, C.D. (2010). Buddhism and Dalits: Social Philosophy and Traditions. Delhi: Kalpaz Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-7835-792-8.

- ^ P. 151 Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World By André Wink

- ^ P. 164 Notes on the religious, moral, and political state of India before the Mahomedan invasion, chiefly founded on the travels of the Chinese Buddhist priest Fai Han in India, A.D. 399, and on the commentaries of Messrs. Remusat, Klaproth, Burnouf, and Landresse, Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Sykes by Sykes, Colonel;

- ^ P. 505 The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians by Henry Miers Elliot, John Dowson

- ^ Eggermont, Pierre Herman Leonard (1975). Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 9789061860372.

- ^ The case of Karachi, Pakistan

- ^ The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Diewel-Sind (Pakistan) in the 17th and 18th centuries, Floor, W. Institute of Central & West Asian Studies, University of Karachi, 1993–1994, p. 49.

- ^ "The Dutch East India Company's shipping between the Netherlands and Asia 1595–1795". 2 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-14.

- ^ Gayer, Laurent (2014). Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-935444-3.

- ^ Harris, Christina Phelps (1969). "The Persian Gulf Submarine Telegraph of 1864". The Geographical Journal. 135 (2): 169. Bibcode:1969GeogJ.135..169H. doi:10.2307/1796823. ISSN 1475-4959. JSTOR 1796823.

- ^ Fieldman, Herbert (1960). Karachi through a hundred years. UK: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "CHOLERA IN THE PUNJAUB". The North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times. Vol. 1, no. 61. Tasmania, Australia. 29 May 1899. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-03-07 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Port Qasim | About Karachi". Port Qasim Authority. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ A story behind every name

External links

- A story behind every name

- History of Karachi with old & new Pictures Archived 2013-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- 'Traitor of Sindh' Seth Naomal: A case of blasphemy in 1832

- The real Father of Karachi (it's not who you think)

- The real Father of Karachi — II

- Of streets and names

- Harchand Rai Vishan Das: Karachi's beheaded benefactor

- Karachi's Polo Ground: Digging into history

- Ranchor Line: 14 acres of an abandoned identity

- Mr. Strachan and Maulana Wafaai

- The Clifton of yore

- Karachi's Ranchor Line: Where red chilli is no more