Blood quota: Difference between revisions

remove PROD, was previously PRODed 22:21, 23 June 2024 and later removed, must go to WP:AFD |

Nominated for deletion; see Wikipedia:Articles for deletion/Blood quota. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Concept of Gonzalo Thought}} |

{{Short description|Concept of Gonzalo Thought}} |

||

<!-- Please do not remove or change this AfD message until the discussion has been closed. --> |

|||

{{Article for deletion/dated|page=Blood quota|timestamp=20241117030156|year=2024|month=November|day=17|substed=yes|help=off}} |

|||

<!-- Once discussion is closed, please place on talk page: {{Old AfD multi|page=Blood quota|date=17 November 2024|result='''keep'''}} --> |

|||

<!-- End of AfD message, feel free to edit beyond this point --> |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2024}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2024}} |

||

{{Use American English|date=June 2024}} |

{{Use American English|date=June 2024}} |

||

Revision as of 03:01, 17 November 2024

An editor has nominated this article for deletion. You are welcome to participate in the deletion discussion, which will decide whether or not to retain it. |

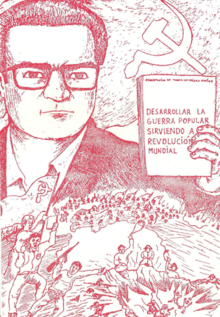

The blood quota (Spanish: cuota de sangre) is a concept developed by Abimael Guzmán, leader of the Shining Path, through which a communist militant must sacrifice their life for the world proletarian revolution.[1][2] As part of the blood quota communist militants willfully promoted hatred and violence to attract adherents, instrumentalizing the masses in their favor and tolerating cruelty against their opponents to gain obedience, viewing violence as a necessary element on the path to communism and death as a heroic act.[3] As such, it formed a core tenet of Gonzalo Thought.

The implementation of the "Blood Quota" led to widespread atrocities, including targeted assassinations, bombings, massacres, and other acts of terrorism.[4] The Shining Path's campaign of violence resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and widespread suffering across Peru until Guzman's capture in the early 1990s.[5]

Background

The Shining Path believed in the necessity of a violent revolution to overthrow the Peruvian government and establish a communist state. The concept of the "Blood Quota" was an integral part of Gonzalo thought and reflected the belief that a certain number of people needed to be killed or sacrificed in order to achieve their revolutionary goals. Increasing conflicts and radicalizing oppositions cannot have any other effect than to accelerate history, bringing closer the day of final triumph.[3]

This notion itself is rooted in Maoist ideology, which advocated for the use of violence and protracted people's war as a means of achieving a communist revolution.[6]

The People's War

Guzmán announced that “the triumph of the revolution will cost a million deaths.”[7] "Paying the quota" meant that the senderista would "cross rivers of blood" for the triumph of the "people's war".[7] The aim was to incite the Peruvian State to carry out acts of violence against the civilian population so that, in this way, the Shining Path could obtain popular support and the capacity for mass mobilization: the violence of the reaction had revolutionary effects by growing hatred and a desire for revenge among those affected, which in turn would lead to an acceleration of the ruin of the old order.[3]

In December 1982 President Fernando Belaúnde declared a state of emergency and ordered that the Peruvian Armed Forces fight the Shining Path, granting them extraordinary powers.[8] Military leadership adopted practices used by Argentina during the Dirty War, committing state terrorism, with entire villages being massacred by the armed forces while civilians endured forced disappearance.[9][8] When the military started organizing peasant militias ("rondas") to fight Senderistas, the Shining Path heavily retaliated: during the Lucanamarca massacre, nearly 70 indigenous people were murdered. The youngest victim was six months old, the oldest about seventy.[10] Most were killed by machete and axe hacks; some were shot in the head at close range.[10] Discussing the massacre, Guzman asserted that "the main point was to make them understand that we were a hard nut to crack, and that we were ready for anything, anything (..)".[11]

Media depiction

The violence perpetuated by the Shining Path and the government inspired Alonso Cueto to write about the insecurity of the period,[12] with his most well-known novel The Blue Hour (2005) being adapted into an eponymous movie in 2014.

See also

References

- ^ "El ocaso de Sendero y la muerte de Guzmán". noticiasser.pe (in Spanish). 13 September 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Roncagliolo, Santiago (2007). La cuarta espada: la historia de Abimael Guzmán y Sendero Luminoso. Barcelone: Debate. ISBN 978-84-8306-738-3.

- ^ a b c Portocarrero Maisch, Gonzalo (2014). Razones de sangre (2nd ed.). Fondo Editorial de la PUC. pp. 27–35. ISBN 978-612-4146-92-3.

- ^ Burt, Jo-Marie (October 2006). "'Quien habla es terrorista': The political use of fear in Fujimori's Peru". Latin American Research Review. 41 (3): 38. doi:10.1353/lar.2006.0036.

- ^ Sierra, Jerónimo Ríos (16 September 2021). "Abimael Guzmán, Sendero Luminoso y la cuota de sangre". Latinoamérica 21 (in European Spanish). Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Priestland, Davis (2009). The Red Flag: A History of Communism. New York: Grove Press. p. 253.

- ^ a b "Actors of the armed conflict" (PDF). Truth and reconciliation commission. p. 128.

- ^ a b Werlich, David P. (January 1987). "Debt, Democracy and Terrorism in Peru". Current History. 86 (516): 29–32, 36–37. doi:10.1525/curh.1987.86.516.29. S2CID 249689936.

- ^ Mauceri, Philip (Winter 1995). "State reform, coalitions, and the neoliberal 'autogolpe' in Peru". Latin American Research Review. 30 (1): 7–37. doi:10.1017/S0023879100017155. S2CID 252749746.

- ^ a b Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. 28 August 2003. "La Masacre de Lucanamarca (1983)". Accessed 10 February 2008. (in Spanish)

- ^ "2.6. La masacre de Lucanamarca (1983)" (PDF). Truth and reconciliation commission.

- ^ Camacho Delgado, José Manuel (2006). "Alonso Cueto y la novela de las víctimas". Caravelle (1988-) (86): 249. doi:10.3406/CARAV.2006.2930. ISSN 1147-6753. JSTOR 40854252. S2CID 144636543.