Lima: Difference between revisions

AlejandroFC (talk | contribs) |

AlejandroFC (talk | contribs) Merged "Wall of Shame (Peru)" article with the relevant section and toned down the language. |

||

| Line 891: | Line 891: | ||

====Wall of Shame==== |

====Wall of Shame==== |

||

The mid-20th century saw the rural population (between 600,000 and 1 million people) taking refuge in Lima, especially during the [[Peruvian conflict]].<ref name=vatik/> The new arrivals, often very poor, erected hastily built shacks. Some residents of these shantytown neighborhoods have acquired property titles, but urban planning remains largely non-existent. In response, a number of wealthy neighbourhoods built their own security barriers starting in 1985, citing security concerns.<ref name=vatik/> By 2019, some segments were up to 3 metres high and included [[barbed wire]],<ref>[https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2023-09-01/peru-tears-down-lima-wall-of-shame-but-wealth-divide-stays-strong https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2023-09-01/peru-tears-down-lima-wall-of-shame-but-wealth-divide-stays-strong] ''[[USA Today]]''</ref> having a total length of {{convert|10|km|spell=in}}.<ref>{{Cite news |title=El polémico muro que separa a ricos y pobres en Lima |last=Pighi |first=Pierina |date=2015-10-21 |url=https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/10/151019_peru_muro_barrio_pobre_rico_lima_amv |work=[[BBC Mundo]]|language=Spanish}}</ref><ref name="NACLA">{{Cite journal |last=Campoamor |first=Leigh |date=2019 |title=Lima's Wall(s) of Shame: In the hills of Lima, a concrete wall divides a poor neighborhood from a wealthy gated community, marking a border defined by centuries of structural neglect. |journal=[[NACLA Report on the Americas]] |volume=51 |issue=1 |pages=29–35 |doi=10.1080/10714839.2019.1593686 |s2cid=167067331}}</ref> |

|||

Critis have used the term '''wall of shame''' ({{langx|es|muro de la vergüenza}}) to refer to the barriers, which are the subject of tension, especially as many inhabitants of the poorer area cross the wall everyday to work in the neighbouring affluent areas, usually as gardeners or domestic workers.<ref name="Atlantic">{{Cite news |last=Janetsky |first=Megan |date=7 September 2019 |title=Lima's 'Wall of Shame' and the Art of Building Barriers |work=The Atlantic |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/09/peru-lima-wall/597085/ |url-status=live |access-date=6 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201127064755/https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/09/peru-lima-wall/597085/ |archive-date=27 November 2020}}</ref> The wall was partially demolished in 2023 in a number of places.<ref>Bourke, Mary (13 June, 2024) [https://www.medlifemovement.org/medlife-stories/global-topics/the-wall-of-shame-in-lima-peru-a-symbol-of-class-divide/ The Wall of Shame in Lima, Peru: A Symbol of Class Divide]. ''MEDLIFE''. Retrieved 2024-11-16.</ref><ref name=vatik>{{Cite news |title=Derriban el "muro de la vergüenza" de Lima después de cuatro décadas |last=Piro |first=Isabella |date=2023-09-07 |url=https://www.vaticannews.va/es/mundo/news/2023-09/derriban-muro-de-la-verguenza-de-lima-despues-de-cuatro-decadas.html |access-date=2024-11-14 |work=[[Vatican News]] |language=Spanish}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |title=Peru tears down Lima 'wall of shame' but wealth divide stays strong |date=2023-09-01 |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/peru-tears-down-lima-wall-shame-wealth-divide-stays-strong-2023-09-01/ |access-date=2024-11-15 |work=[[Reuters]]}}</ref> |

|||

==Notable people== |

==Notable people== |

||

Latest revision as of 05:27, 20 November 2024

Lima

Ciudad de Los Reyes | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): Ciudad de los Reyes (City of the Kings) La Tres Veces Coronada Villa (The Three Times Crowned Ville) La Perla del Pacífico (The Pearl of the Pacific) | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 12°03′36″S 77°02′15″W / 12.06000°S 77.03750°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | Lima |

| Established | 18 January 1535 |

| Founded by | Francisco Pizarro |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipalidad |

| • Body | Municipality of Lima |

| • Mayor | Rafael López Aliaga |

| Area | |

• City | 2,672.3 km2 (1,031.8 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 800 km2 (300 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,819.3 km2 (1,088.5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0–1,550 m (0–5,090 ft) |

| Population (2023)[3] | |

| • Rank | 2nd in South America 1st in Peru |

| • Urban | 9,751,717 |

| • Urban density | 12,000/km2 (32,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 11,283,787[2] |

| • Metro density | 4,002.3/km2 (10,366/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | Limeño/a |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $210.4 billion[4] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Peru Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | (Not Observed) |

| UBIGEO | 15000 |

| Area code | 1 |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Lima |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Designated | 1988, 1991 (12th, 15th sessions) |

| Reference no. | 500 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Lima (/ˈliːmə/ LEE-mə; locally [ˈlima]), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (locally [sjuˈdat de los ˈreʝes], Spanish for "City of Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of the country, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The city is considered the political, cultural, financial and commercial center of Peru. Due to its geostrategic importance, the Globalization and World Cities Research Network has categorized it as a "beta" tier city. Jurisdictionally, the metropolis extends mainly within the province of Lima and in a smaller portion, to the west, within the Constitutional Province of Callao, where the seaport and the Jorge Chávez Airport are located. Both provinces have regional autonomy since 2002.

The 2023 census projection indicates that the city of Lima has an estimated population of 10,092,000 inhabitants, making it the most populated city in the country, and the second most populous in the Americas after São Paulo.[5][6] Together with the seaside city of Callao, it forms a contiguous urban area known as the Lima Metropolitan Area, which encompasses a total of 10,151,200 inhabitants.[5][note 1] When considering the constitutional province of Callao, the total agglomeration reaches a population of 11,342,100 inhabitants, one of the thirty most populated urban agglomerations in the world. The city is marked by severe urban segregation between the poor pueblos jóvenes, populated in large part by immigrants from the Andean highlands, and wealthy neighbourhoods. From 1985 onwards, barriers known as "walls of shame" run across much of the city separating rich areas from the poor.[7][8]

Lima was named by natives in the agricultural region known by native Peruvians as Limaq. It became the capital and most important city in the Viceroyalty of Peru. Following the Peruvian War of Independence, it became the capital of the Republic of Peru (República del Perú). Around one-third of the national population now lives in its metropolitan area.

In October 2013, Lima was chosen to host the 2019 Pan American Games; these games were held at venues in and around Lima, and were the largest sporting event ever hosted by the country. It also hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Meetings of 2008 and 2016, the Annual Meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group in October 2015, the United Nations Climate Change Conference in December 2014, and the Miss Universe 1982 contest. In November 2024, it hosted the APEC summit for the third time.[9]

Etymology

[edit]According to early Spanish articles, the Lima area was once called Itchyma,[citation needed] after its original inhabitants. However, even before the Inca occupation of the area in the 15th century, a famous oracle in the Rímac Valley had come to be known by visitors as Limaq (Limaq, pronounced [ˈli.mɑq], which means "talker" or "speaker" in the coastal Quechua that was the area's primary language before the Spanish arrival). This oracle was eventually destroyed by the Spanish and replaced with a church, but the name persisted: the chronicles show "Límac" replacing "Ychma" as the common name for the area.[10]

Modern scholars speculate that the word "Lima" originated as the Spanish pronunciation of the native name Limaq. Linguistic evidence seems to support this theory, as spoken Spanish consistently rejects stop consonants in word-final position.

The city was founded in 1535 under the name City of Kings (Spanish: Ciudad de los Reyes), because its foundation was decided on January 6, date of the feast of the Epiphany. This name quickly fell into disuse, and Lima became the city's name of choice; on the oldest Spanish maps of Peru, both Lima and Ciudad de los Reyes can be seen together.

The river that feeds Lima is called Rímac, and many people erroneously assume that this is because its original Inca name is "Talking River" (the Incas spoke a highland variety of Quechua, in which the word for "talker" was pronounced [ˈrimɑq]).[11] However, the original inhabitants of the valley were not Incas. This name is an innovation arising from an effort by the Cuzco nobility in colonial times to standardize the toponym so that it would conform to the phonology of Cuzco Quechua.

Later, as the original inhabitants died out and the local Quechua became extinct, the Cuzco pronunciation prevailed. Nowadays, Spanish-speaking locals do not see the connection between the name of their city and the name of the river that runs through it. They often assume that the valley is named after the river; however, Spanish documents from the colonial period show the opposite to be true.[10]

Symbols

[edit]Flag

[edit]The Flag of Lima is historically known as "Banner of the City of the Kings of Peru". It is formed by a golden-colored silk canvas and in the center is the embroidered coat of arms of the city.[12]

Coat of arms

[edit]The coat of arms of Lima was granted by the Spanish Crown on 7 December 1537, through a real cédula signed in Valladolid by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and his mother, Queen Joanna of Castile. It is formed by a main field azure, with three gold crowns of kings placed in a triangle and above them a gold star that touches the three crowns with its points, and in the orle some gold letters that say: Hoc signum vere regum est (This is the true sign of the kings). Outside the shield are the initials I and K (Ioana and Karolus), which are the names of Queen Joanna and her son Charles V. A star is placed above the letters and two crowned sabre-faced eagles embracing them, which hold the coat of arms.

Anthem

[edit]The anthem of Lima was heard for the first time on 18 January 2008, in a solemn session that was attended by the then President of Peru Alan García, the mayor of the city Luis Castañeda Lossio and various authorities. Those in charge of creating the anthem were the councillors Luis Enrique Tord (author of the lyrics), Euding Maeshiro (composer of the melody) and the musical producer Ricardo Núñez (arranger).[13]

History

[edit]Pre-Columbian era

[edit]

Although the history of the city of Lima began with its Spanish foundation in 1535, the territory formed by the valleys of the Rímac, Chillón and Lurín rivers was occupied by pre-Inca settlements, which were grouped under the Lordship of Ichma.[15] The Maranga culture and the Lima culture were the ones that established and forged an identity in these territories. During those times, the sanctuaries of Lati (current Puruchuco) and Pachacámac (the main pilgrimage sanctuary during the time of the Incas) were built, it was built from 3rd century to 15th century by several civilizations, and which was used even until the time the Spanish conquistadors arrived.

These cultures were conquered by the Wari Empire during the height of its imperial expansion. It is during this time that the ceremonial center of Cajamarquilla was built.[16][17] As Wari importance declined, local cultures regained autonomy, highlighting the Chancay culture. Later, in the 15th century, these territories were incorporated into the Inca Empire.[18] From this time we can find a great variety of huacas throughout the city, some of which are under investigation.

The most important or well-known huacas are those of Huallamarca, Pucllana, and Mateo Salado, all located in the middle of Lima districts with very high urban growth, so they are surrounded by business and residential buildings; however, that does not prevent its perfect state of conservation.

During the time of the Incas, the valley of Lima was highly populated and organized into an Inca province, or huamani (wamani), called Pachacamac. The colonial Spanish historian Bernabé Cobo mentions that the huamani of Pachacamac was subdivided into three hunu of tributary men, rather than the conventional four hunu. It has also been argued that a fourth hunu may have existed but was not recorded.[19] The primary meaning of the word hunu in Quechua is 10,000, leading to the assumption that 30,000 families lived in the valley. This assumption has been criticized, including by the historian Åke Wedin, because hunu can also mean countless, and therefore could simply refer to a very large group of men. The scholar John Rowe suggested that the valley had a population of about 150,000 during Inca times.[20]

Whatever the case, each recorded hunu of Pachacamac had a head town, corresponding to some of the most populated settlements in the valley: Caraguayllo (Carabayllo), Maranga, and Surco (or Sulco, also known as the archaeological site Armatambo).[19]

... this valley was divided, according to the government of the Inca kings, into three 'unos' or governorships of ten thousand families each; the town of Caraguayllo was the head of the first; that of Maranga, which is situated in the middle of the valley, of the second, and the third, that of Surco; this last town was the largest of all ...[21]

The inhabitants of the pre-Columbian town of Surco were relocated to the modern district of Santiago de Surco early in the colonial period. In addition to Aymara and Quechua, the inhabitants of the northern part of the valley, specifically in the hunu of Carabayllo, spoke an additional language believed to be Quingnam.[22]

Regarding the pre-Hispanic settlement of Lima, it is recorded that this part of the valley, near the Rimac river, was administered by a curaca, or local lord, named Taulichusco. He was a former yana, or servant, of Mama Vilo, one of the wives of Emperor Huayna Capac. Lima was awarded to Taulichusco in recognition of his services to the Inca royalty. Some of Peru's most important buildings were erected on the sites of major constructions of the pre-Hispanic settlement. For example, the residential palace of Taulichusco was located where the modern Palacio de Gobierno of Peru stands today. A temple called Puma Inti once occupied the site where the Cathedral of Lima is now, and the Municipal Theatre of Lima is situated where a pre-Columbian structure, referred to as Huaca El Cabildo by the Spaniards, once stood. These buildings were centered around a plaza, which was later expanded to become the Plaza Mayor. The Huaca de Aliaga and Huaca Riquelme were other major buildings near the plaza. Other nearby constructions included the temple-oracle of Rímac, one of the main places of worship in the valley, also known as the so-called "huaca grande" that once stood in Barrios Altos.[23]

Spanish founding

[edit]

In 1532, the Spanish and their indigenous allies (from the ethnic groups subdued by the Incas) under the command of Francisco Pizarro took monarch Atahualpa prisoner in the city of Cajamarca. Although a ransom was paid, he was sentenced to death for political and strategic reasons. After some battles, the Spanish conquered their empire. The Spanish Crown named Francisco Pizarro governor of the lands he had conquered. Pizarro decided to found the capital in the Rímac river valley,[25] after a failed attempt to establish it in Jauja.

He considered that Lima was strategically located, close to a favorable coast for the construction of a port but prudently far from it in order to prevent attacks by pirates and foreign powers, on fertile lands and with a suitable cool climate. Thus, on 6 January 1535, Lima was founded with the name "City of the Kings", named in this way in honor of the epiphany,[26][27] on territories that had been of the kuraka Taulichusco. The explanation of this name is due to the fact that "around the same time in January, the Spaniards were looking for the place to lay the foundation for the new city, [...] not far from the Pachacámac sanctuary, near the Rímac river.

However, as had happened with the region, initially called New Castile and later Peru, the City of the Kings soon lost its name in favor of "Lima". Pizarro, with the collaboration of Nicolás de Ribera, Diego de Agüero and Francisco Quintero personally traced the Plaza Mayor and the rest of the city grid, building the Viceroyalty Palace (today transformed into the Government Palace of Peru, which hence retains the traditional name of Casa de Pizarro) and the Cathedral, whose first stone Pizarro laid with his own hands.[28] In August 1536, the flourishing city was besieged by the troops of the Inca general Quizu Yupanqui under orders from the monarch Manco Inca Yupanqui who was in Cusco, but the Spanish and their indigenous allies managed to defeat them. The Huaylas (Wayllas) army's assistance was of special importance to the Spanish. The army arrived personally led by Contarhuancho[29] (Kuntur-Wanchu), a secondary wife of the deceased Emperor Wayna Qhapaq and now a respected kuraka of half the province of Huaylas, the Hanan Huaylas or Upper Huaylas moiety. Contarhuancho came to Lima after receiving a plea for help in a quipu message from her daughter, the Huaylas-Inca princess Doña Inés Huaylas Yupanqui.

In the following years, Lima gained prestige by being designated the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru and the seat of a Real Audiencia in 1543. Since the location of the coastal city was conditioned by the ease of communications with Spain, a close bond with the port of Callao was soon established.[30]

Colonial time

[edit]

For the next century, it prospered as the center of an extensive trade network that integrated the viceroyalty with the Americas, Europe, and East Asia. But the city was not without its dangers; violent earthquakes destroyed a large part of it between 1586 and 1687, leading to a great deal of construction activity. It is then when aqueducts, starlings and retaining walls appear before the flooding of the rivers, the bridge over the Rímac is finished, the cathedral is built, and numerous hospitals, convents and monasteries are built. Then we can see that the city is articulated around its neighborhoods. Another threat was the presence of pirates and corsairs in the Pacific Ocean, which motivated the construction of the Walls of Lima between 1684 and 1687.[17]

The 1687 earthquake marked a turning point in the history of Lima, since it coincided with a recession in trade due to economic competition with other cities such as Buenos Aires. With the creation of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717, the political demarcations were reorganized, and Lima only lost some territories that actually already enjoyed their autonomy. In 1746 a strong earthquake severely damaged the city and destroyed Callao, forcing a massive reconstruction effort by Viceroy José Antonio Manso de Velasco.[31]

In the second half of the 18th century, Enlightenment ideas about public health and social control influenced the development of the city. During this period, the Peruvian capital was affected by the Bourbon reforms as it lost its monopoly on foreign trade and its control over the important mining region of Upper Peru. This economic weakening led the elite of the city to depend on the positions granted by the viceregal government and the Church, which contributed to keeping them more linked to the Crown than to the cause of independence.

The greatest political-economic impact that the city experienced at that time occurred with the creation of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776, which changed the course and orientations imposed by the new mercantile traffic. Among the buildings built during this period there is the Coliseo de Gallos, the Acho Bullring and the General Cemetery. The first two were erected to regulate these popular activities, centralizing them in one place, while the cemetery put an end to the practice of burying the dead in churches, considered unhealthy by public authorities.

-

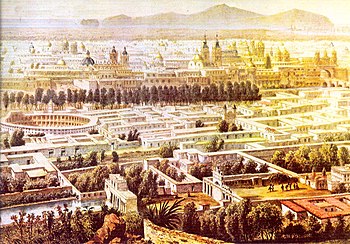

"The City of the Kings of Lima, royal high court, principal city of the kingdom of the Indies, residence of the viceroy[...]", painting of 1615 by the Inca painter Guamán Poma. Royal Library, Denmark.[32]

-

The unfinished cathedral of Lima in the Plaza Mayor, painting of 1680. Museo de América (Madrid).[33]

-

View of Lima and the Tapada limeña (a colonial women fashion) in a painting of 1842 by d'Orbigny and Benoît. Museum of the Americas, Spain.[34]

-

Lima as seem from the Rímac District, painting of 1850 by Batta Molinelli[35]

-

Colonial Calle de los Judíos (Jewish quarter) (Lima) in 1866 by Manuel A. Fuentes and Firmin Didot, Brothers, Sons & Co. University of Chicago Library.[36]

-

Colonial Calles de la Oca and de Bodegones (Lima) in 1866 by Manuel A. Fuentes and Firmin Didot, Brothers, Sons & Co. University of Chicago Library.[36]

-

Puente de Piedra Bridge, the former Arco del Puente Gate and the Walls of Lima in 1878 by El Viajero Ilustrado. Old Fund of the University of Seville.[37]

Independence

[edit]

A combined expedition of Argentine and Chilean independence fighters led by General Don José de San Martín landed in southern Lima in 1820, but did not attack the city. Faced with a naval blockade and guerrilla action on the mainland, Viceroy José de la Serna was forced to evacuate the city in July 1821 to save the Royalist army. Fearing a popular uprising and lacking the means to impose the order, the City Council invited San Martín to enter the city, signing a Declaration of Independence at his request.

Proclaimed the independence of Peru in 1821 by General San Martín,[38] Lima became the capital of the new Republic of Peru. Thus, it was the seat of the government of the liberator and also the seat of the first Constituent Congress that the country had.[39] The war lasted for two more years, during which the city changed hands many times and suffered abuses from both sides. By the time the war was decided, on 9 December 1824, at the Battle of Ayacucho, Lima had been considerably impoverished.

Republican era

[edit]

After the War of Independence, Lima became the capital of the Republic of Peru, but the country's economic stagnation and political disorder paralyzed its urban development. This situation was reversed in the 1850s, when the growing public and private income derived from the export of guano allowed a rapid expansion of the city. In the following twenty years, the State financed the construction of large public buildings to replace the old viceregal establishments, among these are the Central Market, the General Slaughterhouse, the Mental Asylum, the Penitentiary and the Hospital Dos de Mayo. There were also improvements in communications; in 1850 a railway line between Lima and Callao was completed and in 1870 an iron bridge was inaugurated over the Rímac River, baptized as Puente Balta. In 1872 the colonial City Walls were demolished by the US engineer Henry Meiggs under contract with the Peruvian government,[42] in anticipation of further urban growth in the future. However, this period of economic expansion also widened the gap between rich and poor, producing widespread social unrest.

During the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), the Chilean army occupied Lima after defeating Peruvian troops and reserves in the battles of San Juan and Miraflores. The city suffered from the invaders, who looted museums, public libraries and educational institutions. At the same time, angry mobs attacked wealthy citizens and the Asian colony, looting their properties and businesses.

20th century

[edit]At the beginning of the 20th century, the construction of avenues that would serve as a matrix for the development of the city began.[43] The avenues Paseo de la República, Leguía (today called Arequipa), Brasil and the landscaping Salaverry that headed south and Venezuela and Colonial avenues to the west joining the port of Callao.[44]

In the 1930s the great constructions began with the remodeling of the Government Palace of Peru and the Palacio Municipal. These constructions reached their peak in the 1950s, during the government of Manuel A. Odría, when the great buildings of the Ministry of Economy and the Ministry of Education were built (Javier Alzamora Valdez Building, currently the seat of the Superior Court of Justice of Lima), the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Labor and the Hospitals of the Workers' Insurance and of the Employee as well as the National Stadium and several large housing units.[45][46]

Also in those years a phenomenon began that changed the configuration of the city, which was the massive immigration of inhabitants from the interior of the country, producing the exponential growth of the capital's population and the consequent urban expansion.[47] The new populations were settling on land near the center which was used as an agricultural area. The current districts of Lince, La Victoria to the south were populated; Breña and Pueblo Libre to the west; El Agustino, Ate and San Juan de Lurigancho to the east and San Martín de Porres and Comas to the north.

As an emblematic point of this expansion, in 1973 the self-managed community of Villa El Salvador (current district of Villa El Salvador) was created, located 30 km south of the city center and currently integrated into the metropolitan area.[48] In the 1980s, terrorist violence added to the disorderly growth of the city the increase of settlers who arrived as internally displaced persons.[47] In the 1940s, Lima started a period of rapid growth spurred by migration from the Andean region, as rural people sought opportunities for work and education. The population, estimated at 600,000 in 1940, reached 1.9 million by 1960 and 4.8 million by 1980.[49] At the start of this period, the urban area was confined to a triangular area bounded by the city's historic center, Callao and Chorrillos; in the following decades settlements spread to the north, beyond the Rímac River, to the east, along the Central Highway and to the south.[50] The new migrants, at first confined to slums in downtown Lima, led this expansion through large-scale land invasions, which evolved into shanty towns, known as pueblos jóvenes.[51]

Geography

[edit]

The urban area covers about 800 km2 (310 sq mi). It is located on mostly flat terrain in the Peruvian coastal plain, within the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers. The city slopes gently from the shores of the Pacific Ocean into valleys and mountain slopes located as high as 1,550 meters (5,090 ft) above sea level. Within the city are isolated hills that are not connected to the surrounding hill chains, such as El Agustino, San Cosme, El Pino, La Milla, Muleria and Pro hills. The San Cristobal hill in the Rímac District, which lies directly north of the downtown area, is the local extreme of an Andean hill outgrowth.

Metropolitan Lima covers 2,672.28 km2 (1,031.77 sq mi), of which 825.88 km2 (318.87 sq mi) (31%) comprise the actual city and 1,846.40 km2 (712.90 sq mi) (69%) the city outskirts.[52] The urban area extends around 60 km (37 mi) from north to south and around 30 km (19 mi) from west to east. The city center is located 15 km (9.3 mi) inland at the shore of the Rímac River, a vital resource for the city, since it carries what will become drinking water for its inhabitants and fuels the hydroelectric dams that provide electricity to the area. While no official administrative definition for the city exists, it is usually considered to be composed of the central 30 of 43 districts of Lima Province, corresponding to an urban area centered around the historic Cercado de Lima district. The city is the core of the Lima Metro Area, one of the ten largest metro areas in the Americas. Lima is the world's third largest desert city, after Karachi, Pakistan, and Cairo, Egypt.

Climate

[edit]Lima has a mild climate, despite its location in the tropics and in a desert.[53] Lima's proximity to the waters of the Pacific Ocean leads to intense maritime moderation of the temperatures, thereby making the climate much milder than those to be expected for a tropical desert, and thus Lima can be classified as a desert climate (Köppen: BWh) with subtropical temperature ranges.[54] Temperatures rarely fall below 12 °C (54 °F) or rise above 30 °C (86 °F).[55] Two distinct seasons can be identified: summer, December through April, and winter from June through September/October. May and October/November are generally transition months, with a more dramatic warm-to-cool weather transition in later May or/and earlier June.[56] Situated onshore from the cold ocean waters, rainfall is extremely rare in Lima.

The summers, December through April, are sunny, hot, and muggy.[57] Daily temperatures oscillate between lows of 18 to 22 °C (64 to 72 °F) and highs of 25 to 30 °C (77 to 86 °F). Coastal fogs occur in some mornings and high clouds in some afternoons and evenings. Summer sunsets are colorful, known by locals as "cielo de brujas" (Spanish for "sky of witches"), since the sky commonly turns shades of orange, pink, and red around 7 pm.

During winter, June through October, the weather is dramatically different. Grey skies, breezy conditions, higher humidity, and cooler temperatures prevail. Long 10 to 15-day stretches of dark overcast skies are not uncommon. Persistent morning drizzle (garúa) frequently occurs from June through September, coating the streets with a thin layer of water that generally dries up by early afternoon. Winter temperatures vary little between day and night. They range from lows of 14 to 16 °C (57 to 61 °F) and highs of 16 to 19 °C (61 to 66 °F), rarely exceeding 20 °C (68 °F) except in the easternmost districts.[58]

Relative humidity is always very high, particularly in the mornings.[59] High humidity produces brief morning fog in the early summer and a usually persistent low cloud deck during the winter (generally develops in late May and persists until mid-November or even early December). The predominantly onshore flow makes the Lima area one of the cloudiest among the entire Peruvian coast. Lima has only 1284 hours of sunshine a year, 27.9 hours in August and 183 hours in April, which is exceptionally little for its latitude.[60] By comparison, London has an average of 1653 hours, and Moscow 1731. Winter cloudiness prompts locals to seek sunshine in Andean valleys above 500 meters (1,600 ft) above sea level.

While relative humidity is high, rainfall is very low due to strong atmospheric stability. The severely low rainfall impacts the city's water supply, which originates from wells and from rivers that flow from the Andes.[61] Inland districts receive anywhere between 10 and 60 mm (0.4 and 2.4 in) of rainfall per year, which accumulates mainly during the winter. Coastal districts receive only 10 to 30 mm (0.4 to 1.2 in). As previously mentioned, winter precipitation occurs as persistent morning drizzle. These are locally called 'garúa', 'llovizna' or 'camanchacas'. On the other hand, summer rain is infrequent and occurs in the form of isolated light and brief showers. These generally occur during afternoons and evenings when leftovers from Andean storms arrive from the east. The lack of heavy rainfall arises from high atmospheric stability caused, in turn, by the combination of cool waters from semi-permanent coastal upwelling and the presence of the cold Humboldt Current and warm air aloft associated with the South Pacific anticyclone.

Lima's climate (like most of coastal Peru) gets severely disrupted in El Niño events. Coastal waters usually average around 17–19 °C (63–66 °F), but get much warmer (as in 1998 when the water reached 26 °C (79 °F)). Air temperatures rise accordingly.

| Climate data for Lima (Jorge Chávez International Airport), elevation 13 m (43 ft), (2001–2020, extremes 1960–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.7 (90.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.0 (82.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.4 (92.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.1 (80.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

21.8 (71.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.7 (72.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.5 (68.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.8 (0.03) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.7 (0.03) |

1.0 (0.04) |

1.5 (0.06) |

0.7 (0.03) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.2 (0.01) |

6.4 (0.25) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 18.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 83 | 81 | 81 | 83 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 185.2 | 166.3 | 188.5 | 181.9 | 112.9 | 44.6 | 36.4 | 28.5 | 35.2 | 59.9 | 103.4 | 129.9 | 1,272.7 |

| Source 1: Deutscher Wetterdienst (precipitation, humidity and sun 1961–1990)[62][63][64] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[65] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Lima (Campo de Marte), elevation 123 m (404 ft), (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.5 (63.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.8 (71.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

17.4 (63.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.6 (0.02) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.4 (0.02) |

1.3 (0.05) |

2.1 (0.08) |

1.9 (0.07) |

1.2 (0.05) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.3 (0.01) |

9.8 (0.39) |

| Source: National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology of Peru (SENAMHI)[66] | |||||||||||||

Government

[edit]

National

[edit]Lima is the capital city of the Republic of Peru and Lima Province. As such, it is home to the three branches of the Government of Peru.

The executive branch is headquartered in the Government Palace, located in the Plaza Mayor. All ministries are located in the city.

The legislative branch is headquartered in the Legislative Palace and is home to the Congress of the Republic of Peru.

The Judicial branch is headquartered in the Palace of Justice and is home to the Supreme Court of Peru. The Palace of Justice in Lima is seat of the Supreme Court of Justice the highest judicial court in Peru with jurisdiction over the entire territory of Peru.

Lima is seat of two of the 28-second highest or Superior Courts of Justice. The first and oldest Superior Court in Lima is the Superior Court of Justice, belonging to the Judicial District and. Due to the judicial organization of Peru, the highest concentration of courts is located in Lima despite the fact that its judicial district has jurisdiction over only 35 of the 43 districts.[67] The Superior Court of the Cono Norte is the second Superior Court located in Lima and is part of the Judicial District of North Lima. This judicial district has jurisdiction over the remaining eight districts, all located in northern Lima.[68]

Local

[edit]The city is roughly equivalent to the Province of Lima, which is subdivided into 43 districts. The Metropolitan Municipality has authority over the entire city, while each district has its own local government. Unlike the rest of the country, the Metropolitan Municipality, although a provincial municipality, acts as and has functions similar to a regional government, as it does not belong to any of the 25 regions of Peru. Each of the 43 districts has their own district municipality that is in charge of its own district and coordinate with the metropolitan municipality.

Political system

[edit]Unlike the rest of the country, the Metropolitan Municipality has functions of regional government and is not part of any administrative region, according to Article 65. 27867 of the Law of Regional Governments enacted on 16 November 2002, 87 The previous political organization remains in the sense that a Governor is the political authority for the department and the city. The functions of this authority are mostly police and military. The same city administration covers the local municipal authority.

Lima has been rocked by corruption scandals: former mayors Susana Villaran (2011–2014) and Luis Castaneda (2003-2010 and 2014–2018) were remanded in custody as part of the bribery scandal involving the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht. Jorge Munoz (mayor from 2019 to 2022), was removed from office for illegally holding several offices and the related allowances.

International organizations

[edit]Lima is home to the headquarters of the Andean Community of Nations that is a customs union comprising the South American countries of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, among other regional and international organizations.

Demographics

[edit]

With a municipal population of 8,852,000 and 9,752,000 for the metropolitan area and a population density of 3,008.8 inhabitants per square kilometer (7,793/sq mi) as of 2007[update],[69] Lima ranks as the 30th most populous agglomeration in the world, as of 2014[update], and the second biggest city in South America in terms of population within city limits, after São Paulo.[70] Its population features a complex mix of racial and ethnic groups. Mestizos of mixed Amerindian and European (mostly Spanish and Italians) ancestry are the largest ethnic group. European Peruvians are the second largest group. Many are of Spanish, Italian or German descent; many others are of French, British, or Croatian descent.[71][72] The minorities in Lima include Amerindians (mostly Aymara and Quechua) and Afro-Peruvians, whose African ancestors were initially brought to the region as slaves. Jews of European descent and Middle Easterners are there. Lima's Asian community is made up primarily of Chinese (Cantonese) and Japanese descendants, whose ancestors came mostly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The city has, by far, the largest Chinese diaspora in Latin America.[73]

The first settlement in what would become Lima was made up of 117 housing blocks. In 1562, another district was built across the Rímac River and in 1610, the first stone bridge was built. Lima then had a population of around 26,000; blacks made up around 40% and whites made up around 38%.[75] By 1748, the white population totaled 16,000–18,000.[76] In 1861, the number of inhabitants surpassed 100,000 and by 1927, had doubled.[citation needed]

During the early 20th century, thousands of immigrants came to the city, including people of European descent. They organized social clubs and built their own schools. Examples are The American-Peruvian school, the Alianza Francesa de Lima, the Lycée Franco-Péruvien and the hospital Maison de Sante; Markham College, the British-Peruvian school in Monterrico, Antonio Raymondi District Italian School, the Pestalozzi Swiss School and also, several German-Peruvian schools.

Chinese and a lesser number of Japanese came to Lima and established themselves in the Barrios Altos neighborhood in downtown Lima. Lima residents refer to their Chinatown as Barrio chino or Calle Capon and the city's ubiquitous Chifa restaurants – small, sit-down, usually Chinese-run restaurants serving the Peruvian spin on Chinese cuisine – can be found by the dozens in this enclave.

In 2014, the National Institute for Statistics and Information (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica) reported that the population in Lima's 49 districts was 9,752,000 people, including the Constitutional Province of Callao. The city and (metropolitan area) represents around 29% of the national population. Of the city's population 48.7% are men and 51.3% are women. The 49 districts in Metropolitan Lima are divided into 5 areas: Cono Norte (North Lima), Lima Este (East Lima), Constitutional Province of Callao, Lima Centro (Central Lima) and Lima Sur (South Lima). The largest areas are Lima Norte with 2,475,432 people and Lima Este with 2,619,814 people, including the largest single district San Juan de Lurigancho, which hosts 1 million people.[52]

Lima is considered a "young" city. According to INEI, by mid 2014 the age distribution in Lima was: 24.3% between 0 and 14, 27.2% between 15 and 29, 22.5% between 30 and 44, 15.4% between 45 and 59 and 10.6% above 60.[52]

Migration to Lima from the rest of Peru is substantial. In 2013, 3,480,000 people reported arriving from other regions. This represents almost 36% of the entire population of Metropolitan Lima. The three regions that supply most of the migrants are Junin, Ancash and Ayacucho. By contrast only 390,000 emigrated from Lima to other regions.[52]

The annual population growth rate is 1.57%. Some of the 43 metropolitan districts are considerably more populous than others. For example, San Juan de Lurigancho, San Martin de Porres, Ate, Comas, Villa El Salvador and Villa Maria del Triunfo host more than 400,000, while San Luis, San Isidro, Magdalena del Mar, Lince and Barranco have less than 60,000 residents.[52]

A 2005 household survey study shows a socio-economic distribution for households in Lima. It used a monthly family income of 6,000 soles (around US$1,840) or more for socioeconomic level A; between 2,000 soles (US$612) and 6,000 soles (US$1,840) for level B; from 840 soles (US$257) to 2,000 soles (US$612) for level C; from 420 soles (US$128) to 1200 soles (US$368) for level D; and up to 840 soles (US$257) for level E. In Lima, 18% were in level E; 32.3% in level D; 31.7% in level C; 14.6% in level B; and 3.4% in level A. In this sense, 82% of the population lives in households that earn less than 2000 soles (or US$612) monthly. Other salient differences between socioeconomic levels include levels of higher education, car ownership and home size.[77]

In Metropolitan Lima in 2013, the percentage of the population living in households in poverty was 12.8%. The level of poverty is measured by households that are unable to access a basic food and other household goods and services, such as clothing, housing, education, transportation and health. The level of poverty has decreased from 2011 (15.6%) and 2012 (14.5%). Lima Sur is the area in Lima with the highest proportion of poverty (17.7%), followed by Lima Este (14.5%), Lima Norte (14.1%) and Lima Centro (6.2%). In addition 0.2% of the population lives in extreme poverty, meaning that they are unable to access a basic food basket.[52]

Economy

[edit]

Lima is the country's industrial and financial center and one of Latin America's most important financial centers,[78] home to many national companies and hotels. It accounts for more than two-thirds of Peru's industrial production[79] and most of its tertiary sector.

The metropolitan area, with around 7,000 factories,[80] is the main location of industry. Products include textiles, clothing and food. Chemicals, fish, leather and oil derivatives are manufactured and processed.[80] The financial district is in San Isidro, while much of the industrial activity takes place in the west of the city, extending to the airport in Callao. Lima has the largest export industry in South America and is a regional center for the cargo industry. Industrialization began in the 1930s and by 1950, through import substitution policies, manufacturing made up 14% of GNP. In the late 1950s, up to 70% of consumer goods were manufactured in factories located in Lima.[81] The Callao seaport is one of the main fishing and commerce ports in South America, covering over 47 hectares (120 acres) and shipping 20.7 million metric tons of cargo in 2007.[82] The main export goods are commodities: oil, steel, silver, zinc, cotton, sugar and coffee.

As of 2003[update], Lima generated 53% of GDP.[83] Most foreign companies in Peru settled in Lima.

In 2007, the Peruvian economy grew 9%, the largest growth rate in South America.[84] The Lima Stock Exchange rose 185.24% in 2006[85] and in 2007 by another 168.3%,[86] making it then one of the fastest growing stock exchanges in the world. In 2006, the Lima Stock Exchange was the world's most profitable.[87]

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit 2008 and the Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union Summit were held there.

Lima is the headquarters for banks such as Banco de Crédito del Perú, Scotiabank Perú, Interbank, Bank of the Nation, Banco Continental, MiBanco, Banco Interamericano de Finanzas, Banco Financiero, Banco de Comercio and CrediScotia. It is a regional headquarters for Standard Chartered. Insurance companies based in Lima include Rimac Seguros, Mapfre Peru, Interseguro, Pacifico, Protecta and La Positiva.[88]

Tourism

[edit]As the main entry point to the country, Lima has developed an important tourism industry, among which its Historic Center, its archaeological centers, its nightlife, museums, art galleries, festivities and popular traditions stand out. According to Mastercard's Global Destination Cities Index, in 2014, Lima was the most visited city of Latin America and was the 20th city globally, with 5.11 million visitors.[89] In 2019,[90] Lima is the top destination in South America, with 2.63 million international visitors in 2018 and a growth forecast of 10.00% percent for 2019.

The Historic Centre of Lima, which includes part of the districts of Lima and Rímac, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988 due to the importance that the city had during the Viceroyalty of Peru, leaving as testimony a large number of architectural legacies.[92] Highlights include the Basilica and Convent of San Francisco, the Plaza Mayor, the Lima Metropolitan Cathedral, the Basilica and Convent of Santo Domingo, the Palacio de Torre Tagle, among others. The tour of the churches of the city is very popular among tourists. In a short walk through the city center we can find many, several of which date from the 16th and 17th centuries.

Among them, the Lima Metropolitan Cathedral and the Basilica of San Francisco stand out, which are said to be linked by the underground passageways of their catacombs. The Sanctuary and Monastery of Las Nazarenas also stands out, a place of pilgrimage to the Señor de los Milagros (Lord of the Miracles), whose festivities in the month of October constitute the most important religious manifestation of Lima and of all Peruvians. Some sections of the Colonial Walls of Lima can still be seen: such is the case of the Bastion Santa Lucía, remains of the old Spanish fortification built by Viceroy Melchor de Navarra y Rocafull around the city center, whose location adjoins the limit of Barrios Altos and El Agustino.

Likewise, having Lima the privilege of being the only capital in South America with immediate access to the sea, it has wide tourist piers that in recent years have become a great attraction for thousands of tourists, especially in the districts of Miraflores and Barranco, where there is also a wide development in terms of entertainment in these areas, turning the capital into a place with several places of tourism and entertainment.

Until the 1970s, the hotel offer was characterized by having the best hotels in the city in the center of Lima, however, since the early 1990s to date, these establishments have positioned themselves in other areas such as the central-southern area of the capital as in Miraflores, Barranco, Santiago de Surco, Surquillo and San Borja; in addition to the San Isidro district that has the largest hotel building in Peru, the 30-story Westin Libertador.

These fine examples of medieval Spanish fortifications were used to defend the city from attacks by pirates and corsairs. For this, part of the Walls corresponding to the rear area of the Basilica of San Francisco, very close to the Government Palace, was recovered, in which a park was built (called Parque de la Muralla) and in which you can see remains of it.[93] Half an hour from the historic center, in the district of Miraflores you can visit the tourist and entertainment center Larcomar which is located on the cliffs facing the sea.

The city has two traditional zoological parks: the main and oldest is the Parque de las Leyendas, located in the San Miguel district, and the other is the Parque Zoológico Huachipa located east of the city in the Lurigancho-Chosica district. On the other hand, the offer of cinemas is wide and has numerous state-of-the-art rooms (4D) that program international film premieres.

Exclusive beaches are visited during the summer months, which are located on the Pan-American Highway, to the north are the resorts of Santa Rosa and Ancón; Until the 1980s, the latter was the most exclusive in Lima and Peru. Currently, although it maintains its architectural beauty, it is visited by people from all over Lima North and the Center. And to the south of the city, the resorts of Punta Hermosa, Punta Negra, San Bartolo and Pucusana. Numerous restaurants, nightclubs, lounges, bars, clubs and hotels have been opened in such places to cater to bathers.

The suburban district of Cieneguilla, the district of Pachacámac and the district of Chosica provide important tourist attractions among locals. Due to its elevation (over 500 masl), the sun shines in Chosica during the winter, being very visited by the residents of Lima to escape the urban fog.[95]

Society and culture

[edit]Strongly influenced by European, Andean, African and Asian culture, Lima is a melting pot, due to colonization, immigration and indigenous influences.[96] The Historic Centre was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988.

The city is known as the Gastronomical Capital of the Americas, mixing Spanish, Andean and Asian culinary traditions.[97]

Lima's beaches, located along the northern and southern ends of the city, are heavily visited during the summer. Restaurants, clubs and hotels serve the beachgoers.[98] Lima has a vibrant and active theater scene, including classic theater, cultural presentations, modern theater, experimental theater, dramas, dance performances and theater for children. Lima is home to the Municipal Theater, Segura Theater, Japanese-Peruvian Theater, Marsano Theater, British theater, Theater of the PUCP Cultural Center and the Yuyachkani Theater.[99]

Architecture

[edit]The architecture of the capital is characterized by a mixture of styles as reflected in the changes between trends throughout various periods of the city's history. Examples of colonial architecture include structures such as the Basilica and Convent of San Francisco, the Lima Metropolitan Cathedral, and the Palacio de Torre Tagle. These constructions were generally influenced by the styles of Spanish Neoclassicism, Spanish Baroque, and the Spanish Colonial styles.[100]

In the buildings of the historic center you can see over 1,600 balconies dating from the Viceroyalty and Republican times.[101] The types of balconies that the city presents are open balconies, flat, box, continuous, among others. After the Independence of Peru, a gradual shift towards Neoclassical and Art Nouveau styles took place. Many of these constructions were influenced by the French architectural style.

In 1940, the census results reflected the city's major urban problems such as sanitation, housing, work, recreation and transportation. During the following years, the Society of Architects, the Institute of Urbanism, the Grupo Espacio, the magazine El Arquitecto Peruano and the Department of Architecture at the National School of Engineers were created. These entities tried to promote the improvement of urban conditions based on modern principles. Meanwhile, the State promoted the development of collective housing through organizations such as the National Housing Commission (CNV) and the National Office of Planning and Urban Development (ONPU). With the architect Fernando Belaunde as deputy, in 1945 the Housing Plan based on Neighborhood Units was made official.

Some government buildings as well as major cultural institutions were built in this architectural time period. During the 1950s and 1960s, several Brutalist style buildings were built on behalf of the military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado. Examples of this architecture are the Museo de la Nación and the Peruvian Ministry of Defense. The 20th century saw the appearance of glass skyscrapers, particularly around the city's financial district. There are also several new architectural projects and real estate.

Language

[edit]Known as Peruvian Coast Spanish, Lima's Spanish is characterized by the lack of strong intonations as found in many other Spanish-speaking regions. It is heavily influenced by Castilian Spanish. Throughout the Viceroyalty era, most of the Spanish nobility based in Lima were originally from Castile.[102] Limean Castillian is also characterized by the lack of voseo, unlike many other Hispanic American countries. This is because voseo was primarily used by Spain's lower socioeconomic classes, a social group that did not begin to appear in Lima until the late colonial era.[citation needed]

Limean Spanish is distinguished by its clarity in comparison to other Latin American accents and has been influenced by immigrant groups including Italians, Andalusians, West Africans, Chinese and Japanese. It also has been influenced by anglicisms as a result of globalization, as well as by Andean Spanish and Quechua, due to migration from the Andean highlands.[103]

Museums

[edit]

Lima is home to the country's highest concentration of museums, most notably the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Museum of Art, the Museo Pedro de Osma, the Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the Nation, The Sala Museo Oro del Perú Larcomar, the Museum of Italian Art, the Museum of Gold and the Larco Museum. These museums focus on art, pre-Columbian cultures, natural history, science and religion.[104] The Museum of Italian Art shows European art.

-

The Museo de la Nación houses thousands of artifacts spanning the entire span of human occupation in Peru.

-

The Museo Pedro de Osma houses artistic objects dating from the 16th to 18th centuries, including paintings, sculptures, altarpieces, silverware, Huamanga stone carvings, furniture and other objects from regions with an ancient Andean artistic tradition.

-

Larco Museum is a privately owned museum of pre-Columbian art that is housed in an 18th-century vice-royal building built over a 7th-century pre-Columbian pyramid.

-

National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History of Peru is the largest and oldest museum in Peru.

Food

[edit]

Lima is known as the Gastronomical Capital of the Americas. A center of immigration and the center of the Spanish Viceroyalty, chefs incorporated dishes brought by the conquistadors and waves of immigrants: African, European, Chinese and Japanese.[97] Since the second half of the 20th century, international immigrants were joined by internal migrants from rural areas.[105] Lima cuisines include Creole food, Chifas, Cebicherias and Pollerias.[106] The city is home to Central Restaurante, which holds the title as Best restaurant in the world, be voted for the title in 2023.

In the 21st century, its restaurants became recognized internationally.[107]

In 2007, the Peruvian Society for Gastronomy was born with the objective of uniting Peruvian gastronomy to put together activities that would promote Peruvian food and reinforce the Peruvian national identity. The society, called APEGA, gathered chefs, nutritionists, institutes for gastronomical training, restaurant owners, chefs and cooks, researchers and journalists. They worked with universities, food producers, artisanal fishermen and sellers in food markets.[108] One of their first projects (2008) was to create the largest food festival in Latin America, called Mistura ("mixture" in Portuguese). The fair takes place in September every year. The number of attendees has grown from 30,000 to 600,000 in 2014.[109] The fair congregates restaurants, food producers, bakers, chefs, street vendors and cooking institutes from for ten days to celebrate excellent food.[110]

Since 2011, several Lima restaurants have been recognized as among The World's 50 Best Restaurants.[111] In 2023, Central was named the Best Restaurant in the World.[112]

| Year | Astrid y Gaston | Central | Maido |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 42 | – | – |

| 2012 | 35 | – | – |

| 2013 | 14 | 50 | – |

| 2014 | 18 | 15 | – |

| 2015 | 14 | 4 | 44 |

| 2016 | 30 | 4 | 13 |

| 2017 | 33 | 5 | 8 |

| 2018 | 39 | 6 | 7 |

| 2019 | – | 6 | 10 |

| 2021 | - | 4 | 7 |

| 2022 | - | 2 | 11 |

| 2023 | - | 1 | 6 |

In 2016, Central was awarded No. 4 (chefs Virgilio Martinez and Pia Leon), Maido was awarded No. 13 (chef Mitsuharu Tsumura) and Astrid & Gaston was awarded No. 30 (chef Diego Muñoz and owned by chef Gaston Acurio).[113] In addition, Central was named No. 1 restaurant in the list of Latin America's 50 Best Restaurants 2015. Out of the 50 best restaurants in Latin America, we find: Central #1, Astrid & Gaston #3, Maido #5, La Mar #12, Malabar #20, Fiesta #31, Osso Carnicería y Salumería #34, La Picanteria #36 and Rafael #50.[114] These restaurants fuse ideas from across the country and the world.

In 2023, Central was named the Best Restaurant in the World.[112]

Peruvian coffee and chocolate have also won international awards.[107]

Lima is the Peruvian city with the greatest variety and where different dishes representing South American cuisine can be found.

Ceviche is Peru's national dish and it's made from salt, garlic, onions, hot Peruvian peppers, and raw fish that's all marinated in lime. In Northern Peru, one can find black-oyster ceviche, mixed seafood

ceviche, crab and lobster ceviche. In the Andes one can also find trout ceviche and chicken ceviche.[115]

About 1.7 million residents are not connected to the drinking water system and are forced to buy water from tankers, even though it is not always safe to drink. The problem of access to water continues to worsen due to drought, pollution, poor infrastructure, overexploitation by large companies and intensive agriculture.[116]

Religion

[edit]

The arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in Peru meant the introduction of the Catholic religion in this area populated by aborigines of various ethnic groups, who followed animist and polytheistic religions,[117][118][119] which produced a religious syncretism. Through a long process of indoctrination and practices among the pre-Columbian settlers, the Spanish friars made faith their most important task. The city of Lima, capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, became in the 17th century a city of monastic life where saints such as Rose of Lima (patron saint of Catholics in Lima, of National Police of Peru, of the Republic of Peru, of the American continent and of the Philippines) and Martín de Porres.

The Peruvian capital is the seat of the Archdiocese of Lima, which was established in 1541 as a diocese and in 1547 as an archdiocese.[120] It is one of the oldest Ecclesiastical Provinces in the Americas. Currently the Archdiocese of Lima is in charge of Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani.[121] The city also has two mosques of the Muslim religion,[122] three synagogues of the Jewish religion,[123] a temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints located in La Molina,[124] a church of the Eastern Orthodox religion located in the district of Pueblo Libre,[125] five Buddhist temples[126] and six prayer rooms of the Church of God Ministry of Jesus Christ International[127]

According to the 2007 Peru Census, 82.83% of Lima residents over the age of twelve declared they were Catholic, while 10.90% profess the Evangelical religion, 3.15% belong to other religions and 3.13% do not specify any religious affiliation.[128] One of the most prominent Catholic religious manifestations in the capital is the procession of the Señor de Los Milagros (Lord of Miracles),[129] whose image dating from the colonial era goes out in procession through the streets of the city in the month of October of each year. The Señor de Los Milagros was named Patron of the city by the Cabildo of Lima in 1715 and Patron of Peru in 2010.

Sports

[edit]The city has sports venues for football, golf, volleyball and basketball, many within private clubs. A popular sport among Limenos is fronton, a racquet sport similar to squash invented in Lima. The city is home to seven international-class golf links. Equestrianism is popular in Lima with private clubs as well as the Hipódromo de Monterrico horse racing track. The most popular sport in Lima is football with professional club teams operating in the city.

-

Plaza de toros de Acho; the plaza is classified as a national historic monument. It is the oldest bullring in the Americas.

-

National Stadium of Peru; its current capacity is 50,000 seats as stated by the Peruvian Football Federation.

-

Estadio Monumental "U" is the highest capacity football stadium in South America and one of the largest in the world.

-

Lima Golf Club (San Isidro District)

-

Campo de Marte is one of the largest parks in the metropolitan area of Lima.

The historic Plaza de toros de Acho, located in the Rímac District, a few minutes from the Plaza de Armas, holds bullfights yearly. The season runs from late October to December. It also holds concerts, conventions and small football matches. The bullring is the oldest in the Americas and the second oldest in the world. It has a capacity of 14,000.

The 131st IOC Session was held in Lima. The meeting saw Paris elected to host the 2024 Summer Olympics and Los Angeles elected to host the 2028 Summer Olympics.

Lima was going to have 2 venues for the 2019 FIFA U-17 World Cup and the 2023 FIFA U-17 World Cup, however, they were stripped of hosting rights in the two tournaments. The city hosted the 2004 Copa América and 2005 FIFA U-17 World Championship and hosted the final of those tournaments. Lima were also the hosts of 2019 Pan American Games.[130] In 2024, they were selected once again to host the 2027 Pan American Games.

| Club | Sport | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peruvian Institute of Sport | Various | Various | Estadio Nacional (Lima) |

| Club Universitario de Deportes | Football | Peruvian Primera División | Estadio Monumental "U" |

| Alianza Lima | Football | Peruvian Primera División | Estadio Alejandro Villanueva |

| Sporting Cristal | Football | Peruvian Primera División | Estadio Alberto Gallardo |

| Deportivo Municipal | Football | Peruvian Segunda División | Estadio Iván Elías Moreno |

| CD Universidad San Martín | Football | Peruvian Segunda División | Estadio Iván Elías Moreno |

| Regatas Lima | Various | Various | Regatas Headquarters Chorrillos |

| Real Club Lima | Basketball, Volleyball | Various | San Isidro |

Subdivisions

[edit]

Northern Lima

Southern Lima

Eastern Lima

Lima is made up of thirty-one densely populated districts, each headed by a local mayor and the Mayor of Lima, whose authority extends to these and the twelve outer districts of the Lima province.

The city's historic center is located in the Cercado de Lima district, locally known as simply Lima, or as "El Centro" ("Center"). It is home to most of the vestiges the colonial past, the Presidential Palace (Spanish: Palacio de Gobierno), the Metropolitan Municipality and (Spanish: Consejo municipal metropolitano de Lima), Chinatown and dozens of hotels, some operating and some defunct, that cater to the national and international elite.

The upscale San Isidro District is the city's financial center. It is home to politicians and celebrities. San Isidro has parks, including Parque El Olivar, which is home to olive trees imported from Spain during the seventeenth century. The Lima Golf Club, a prominent golf club, is located within the district.

Another upscale district is Miraflores, which has luxury hotels, shops and restaurants. Miraflores has parks and green areas, more than most other districts. Larcomar, a shopping mall and entertainment center built on cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, featuring bars, dance clubs, movie theaters, cafes, shops, boutiques and galleries, is also located in this district. Nightlife, shopping and entertainment center around Parque Kennedy, a park in the heart of Miraflores.[131]

La Molina, San Borja, Santiago de Surco -home to the American Embassy and the exclusive Club Polo Lima – are the other three wealthy districts. The middle class districts in Lima are Jesús María, Lince, Magdalena del Mar, Pueblo Libre, San Miguel and Barranco.

The most densely populated districts lie in Northern and Southern Lima, where the suburbs of the city begin (Spanish: Cono Norte and Cono Sur, respectively) and they are mostly composed of Andean immigrants who arrived during the mid- and late- 20th century looking for a better life and economic opportunity, or as refugees of the country's internal conflict with the Shining Path during the late 1980s and early 1990s. In the case of Cono Norte (now called Lima Norte), shopping malls such as Megaplaza and Royal Plaza were built in the Independencia district, on the border with the Los Olivos District (the most residential neighborhood in the northern part). Most inhabitants are middle or lower middle class.

Barranco, which borders Miraflores by the Pacific Ocean, is the city's bohemian district, home or once home of writers and intellectuals including Mario Vargas Llosa, Chabuca Granda and Alfredo Bryce Echenique. This district has restaurants, music venues called "peñas" featuring the traditional folk music of coastal Peru (in Spanish, "música criolla") and Victorian-style chalets. Along with Miraflores it serves as the home to the foreign nightlife scene.

Education

[edit]

Home to universities, institutions and schools, Lima has the highest concentration of institutions of higher learning on the continent. In Lima is the oldest continuously operating university in the New World, National University of San Marcos, founded in 1551.[132]

Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería (UNI) was founded in 1876 by Polish engineer Edward Habich and is the country's most important engineering school. Other public universities offer teaching and research, such as the Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal (the second largest), the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (where ex-president Alberto Fujimori once taught) and the National University of Callao.

The Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, established in 1917, is the oldest private university. Other private institutions include Universidad del Pacifico, Universidad ESAN, Universidad de Lima, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Universidad Cientifica del Sur, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista and Universidad Ricardo Palma.[133]

The city and has a total of 8,047 elementary and high schools, both public and private, which educate more than one and a half million students. The number of private schools is much greater than public schools (6,242 vs 1,805) while the average size of private schools is 100 for elementary and 130 for high school. Public schools average 400 students in elementary and 500 in high school.[134]

Lima has one of the country's highest levels of enrollment in high school and preschool. 86.1% of high school-age students are in school, vs the national average of 80.7%. In early childhood, the enrollment level in Lima is 84.7%, while the national average is 74.5%. Early childhood enrollment has improved by 12.1% since 2005. In elementary school, the enrollment in Lima is 90.7%, while the national average for this level is 92.9%.[135]

The dropout rate for Lima is lower than the national average, except for elementary school, which is higher. In Lima, the dropout rate in elementary is 1.3% and 5.7% in high school, while the national average is 1.2% in elementary and 8.3% in high school.[135]

In Peru, students grade second and fourth students take a test called "Evaluacion Censal de Estudiantes" (ECE). The test assesses skills in reading comprehension and math. Scores are grouped in three levels: Below level 1 means that students were not able to respond to even the most simple questions; level 1 means the students did not achieve the expected level in skills but could respond to simple questions; and level 2 means they achieved/exceeded the expected skills for their grade level. In 2012, 48.7% of students in Lima achieved level 2 in reading comprehension compared to 45.3% in 2011. In math, only 19.3% students achieved level 2, with 46.4% at level 1 and 34.2% less than level 1. Even though the results for Math are lower than for reading, in both subject areas performance increased in 2012 over 2011. The city performs much better than the national average in both disciplines.[136]

The educational system in Lima is organized under the authority of the "Direccion Regional de Educacion (DRE) de Lima Metropolitana", which is in turn divided into 7 sub-directions or "UGEL" (Unidad de Gestion Educativa Local): UGEL 01 (San Juan de Miraflores, Villa Maria del Triunfo, Villa El Salvador, Lurin, Pachacamac, San Bartolo, Punta Negra, Punta Hermosa, Pucusana, Santa Maria and Chilca), UGEL 02 (Rimac, Los Olivos, Independencia, Rimac and San Martin de Porres), UGEL 03 (Cercado, Lince, Breña, Pueblo Libre, San Miguel, Magdalena, Jesus Maria, La Victoria and San Isidro), UGEL 04 (Comas, Carabayllo, Puente Piedra, Santa Rosa and Ancon), UGEL 05 (San Juan de Lurigancho and El Agustino), UGEL 06 (Santa Anita, Lurigancho-Chosica, Vitarte, La Molina, Cieneguilla and Chaclacayo) and UGEL 07 (San Borja, San Luis, Surco, Surquillo, Miraflores, Barranco and Chorrillos).[135]

The UGELes with highest results on the ECE 2012 are UGEL 07 and 03 in both reading comprehension and math. UGEL 07 had 60.8% students achieving level 2 in reading comprehension and 28.6% students achieving level 2 in Math. UGEL 03 had 58.5% students achieve level 2 in reading comprehension and 24.9% students achieving level 2 in math. The lowest achieving UGELs are UGEL 01, 04 and 05.[136]

23% of men have completed university education in Lima, compared to 20% of women. Additionally, 16.2% of men have completed non-university higher education along with 17% of women. The average years of schooling in the city is 11.1 years (11.4 for men and 10.9 for women).[52]

Transportation

[edit]Air

[edit]

Lima is served by Jorge Chávez International Airport, located in Callao (LIM). It is the country's largest airport hosting the largest number of domestic and international passengers. It serves as the fourth-largest hub in the Latin American air network. The airport is the hub for most Peruvian airlines, such as ATSA Airlines, Star Perú, JetSmart Perú, Sky Airline Peru and the Peruvian flag carrier, LATAM Perú. Lima possesses five other airports: the Las Palmas Air Force Base, Collique Airport and runways in Santa María del Mar, San Bartolo and Chilca.[137]

Jorge Chávez International Airport is currently undergoing an expansion, with a new terminal being constructed along with an additional runway and multiple commercial areas. These new expansions will consist of the Lima Airport City. The airport will be the first airport city of Latin America and will increase the current airport capacity of 30 million to 40 million passengers. The expansion project will be complete in December 2024[138]

Road

[edit]Lima is a major stop on the Pan-American Highway. Because of its location on the country's central coast, Lima is an important junction in Peru's highway system. Three major highways originate in Lima.

- The Northern Panamerican Highway extends more than 1,330 kilometers (830 mi) to the border with Ecuador connecting the northern districts with many major cities along the northern Peruvian coast.

- The Central Highway (Spanish: Carretera Central) connects the eastern districts with cities in central Peru. The highway extends 860 kilometers (530 mi) with its terminus at Pucallpa near Brazil.

- The Southern Panamerican Highway connects the southern districts to the southern coast. The highway extends 1,450 kilometers (900 mi) to the border with Chile.

The city has a single major bus terminal next to the mall Plaza Norte. This bus station connects to national and international destinations. Other bus stations serve private bus companies around the city. In addition, informal bus stations are located in the south, center and north of the city.

Maritime

[edit]

Lima's proximity to the port of Callao allows Callao to act as the metropolitan area's major port and one of Latin America's largest. Callao hosts nearly all maritime transport for the metropolitan area. A small port in Lurín serves oil tankers due to a nearby refinery. Maritime transport inside Lima city limits is relatively insignificant compared to that of Callao.

A new port is currently being constructed north of Lima in Chancay. The new port will become the largest in South America and is expected to be complete and commence operations in late 2024.

Rail

[edit]

Lima is connected to the Central Andean region by the Ferrocarril Central Andino which runs from Lima through the departments of Junín, Huancavelica, Pasco and Huánuco.[139] Major cities along this line include Huancayo, La Oroya, Huancavelica and Cerro de Pasco. Another inactive line runs from Lima northwards to the city of Huacho.[140] Commuter rail services for Lima are planned as part of the larger Tren de la Costa project. Lima's main railway station is the Desamparados station.

Public

[edit]

Lima's road network is based mostly on large divided avenues rather than freeways. Lima operates a network of nine freeways – the Via Expresa Paseo de la Republica, Via Expresa Javier Prado, Via Expresa Grau, Panamericana Norte, Panamericana Sur, Carretera Central, Via Expresa Callao, Autopista Chillon Trapiche and the Autopista Ramiro Priale.[141]

According to a 2012 survey, the majority of the population uses public or collective transportation (75.6%), while 12.3% uses a car, taxi or motorcycle.[135]

The urban transport system is composed of over 300 transit routes[87] that are served by buses, microbuses and combis.

Taxis are mostly informal and unmetered; they are cheap but feature poor driving habits. Fares are agreed upon before the passenger enters the taxi. Taxis vary in size from small four-door compacts to large vans. They account for a large part of the car stock. In many cases they are just a private car with a taxi sticker on the windshield. Additionally, several companies provide on-call taxi service.[142]

Corredores Complementarios Bus System

[edit]The Integrated Transport System (SIT), is a bus system developed by the local government to reorganize the current system of routes that has become chaotic. One of the main goals of the SIT is to reduce the number of urban routes, renew the bus fleet currently operating by many private companies and to reduce (and eventually replace) most "combis" from the city.

As of July 2020, SIT currently operates 16 routes: San Martin de Porres – Surco (107) Ate – San Miguel (201, 202,204,206 and 209), Rimac – Surco (301,302,303 and 306), San Juan de Lurigancho – Magdalena (404,405,409,412), and Downtown Lima – San Miguel(508)[citation needed]

Colectivos