Churches of Christ: Difference between revisions

→Name: reworded sentence; added a source |

No edit summary Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| polity = [[Congregationalist polity|Congregationalist]] |

| polity = [[Congregationalist polity|Congregationalist]] |

||

| separations = {{plainlist| |

| separations = {{plainlist| |

||

Roman Catholic Church and other demonations(606 A.D-Present) |

|||

*[[Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)]] (1906) |

*[[Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)]] (1906) |

||

*[[Churches of Christ (non-institutional)]] (1960s) |

*[[Churches of Christ (non-institutional)]] (1960s) |

||

Revision as of 15:17, 4 December 2024

| Churches of Christ | |

|---|---|

Old Bethany Church of Christ Building, Bethany, West Virginia | |

| Classification | Evangelical Protestant[1][2] |

| Orientation | Restorationist |

| Polity | Congregationalist |

| Separations | Roman Catholic Church and other demonations(606 A.D-Present)

|

| Congregations | 41,498 (worldwide) 11,790 (U.S.)[3] |

| Members | 2,000,000 (approx.) worldwide;[4] 1,113,362 in the United States (2020)[5] |

| Publications | |

The Churches of Christ, also commonly known as the Church of Christ, is a loose association of autonomous Christian congregations located around the world. Typically, their distinguishing beliefs are that of the necessity of baptism for salvation and the prohibition of musical instruments in worship. Many such congregations identify themselves as being nondenominational.[12] The Churches of Christ arose in the United States from the Restoration Movement of 19th-century Christians who declared independence from denominations and traditional creeds. They sought "the unification of all Christians in a single body patterned after the original church described in the New Testament."[13]: 54

Overview

Modern Churches of Christ have their historical roots in the Restoration Movement, which was a convergence of Christians across denominational lines in search of a return to an original "pre-denominational" form of Christianity.[14][15]: 108 Participants in this movement sought to base their doctrine and practice on the Bible alone, rather than recognizing the traditional councils and denominational hierarchies that had come to define Christianity since the first century A.D.[14][15]: 82, 104, 105 Members of the Churches of Christ believe that Jesus founded only one church, that the current divisions among Christians do not express God's will, and that the only basis for restoring Christian unity is the Bible.[14] They simply identify themselves as "Christians", without using any other forms of religious or denominational identification.[16][17][18]: 213 They aspire to be the New Testament church as established by Christ.[19][20][21]: 106

Members of the church of Christ do not conceive of themselves as a new church started near the beginning of the 19th century. Rather, the whole movement is designed to reproduce in contemporary times the church originally established on Pentecost, A.D. 33. The strength of the appeal lies in the restoration of Christ's original church.

Churches of Christ generally share the following theological beliefs and practices:[14]

- Autonomous, congregational church organization without denominational oversight;[22]: 238 [23]: 124

- Refusal to hold to any formal creeds or informal "doctrinal statements" or "statements of faith", stating instead a reliance on the Bible alone for doctrine and practice;[21]: 103 [22]: 238, 240 [23]: 123

- Local governance[22]: 238 by a plurality of male elders;[23]: 124 [24]: 47–54

- Baptism by immersion of consenting believers[22]: 238 [23]: 124 in the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit for the forgiveness of sins;[14][21]: 103 [23]: 124

- Weekly observance of the Lord's Supper[23]: 124 on Sunday[21]: 107 [22]: 238

- In British congregations, the term "breaking of bread" is commonly used.

- In American congregations, the terms "Communion" or "body and blood" are used.

- Churches of Christ typically offer open communion on the first day of each week, offering the bread and fruit of the vine to all present at each person's self-examination.

- Practice of a cappella singing is the norm in worship,[25] based on New Testament passages teaching to sing for worship, with no mention of instrumental music (and also that worship in church assemblies for centuries in the early Church practiced a cappella singing).[22]: 240 [23]: 125

In keeping with their history, the Churches of Christ claim the New Testament as their sole rule of faith and practice in deciding matters of doctrine and ecclesiastical structure.[26] They view the Old Testament as divinely inspired[21]: 103 and historically accurate, but they do not consider its laws to be binding under the New Covenant in Christ (unless they are repeated in the New Testament) (Hebrews 8: 7–13).[27]: 388 [28]: 23–37 [29]: 65–67 They believe that the New Testament demonstrates how a person may become a Christian (and thus a part of the universal Church of Christ) and how a church should be collectively organized and carry out its scriptural purposes.[14]

Demographics

In 2022, the total membership of Churches of Christ is estimated to be between 1,700,000 and 2,000,000,[30][31] with over 40,000 individual congregations worldwide.[31] In the United States, there are approximately 1,087,559 members and 11,776 congregations.[31] Overall U.S. membership was approximately 1.3 million in 1990 and 1.3 million in 2008.[32]: 5 Estimates of the proportion of the US adult population associated with the Churches of Christ vary from 0.8% to 1.5%.[32]: 5 [33]: 12, 16 Approximately 1,240 congregations, with 172,000 members, are predominantly African-American; 240 congregations with 10,000 members are Spanish-speaking.[34]: 213 The average congregation size is approximately 100 members, with larger congregations reporting over 1,000 members.[34]: 213 In 2000, the Churches of Christ were the 12th largest religious group in the U.S. based on the number of members, but the 4th largest in number of congregations.[35]

Within the U.S., membership in the Churches of Christ has declined by approximately 12% over the period from 1980 through 2007. The current retention rate of young adults graduating from high school appears to be approximately 60%. Membership is concentrated, with 70% of the U.S. membership, in thirteen states. Churches of Christ had a presence in 2,429 counties, placing them fifth behind the United Methodist Church, Catholic Church, Southern Baptist Convention and Assemblies of God – but the average number of adherents per county was approximately 677. The divorce rate was 6.9%, much lower than national averages.[35]

Name

"Church of Christ" is the most common name used by this group. In keeping with their focus of not being a denomination, using Ephesians 1:22–23 as reference to the church being the body of Christ and a body cannot be divided, congregations have identified themselves primarily as community churches and secondarily as Churches of Christ.[34]: 219–220 A much earlier tradition is to identify a congregation as "the church" at a particular location, with no other description or qualifiers.[34]: 220 [36]: 136–137 A primary motivation behind the name is the desire to use a scriptural or Biblical name – to identify the church using a name that is found in the New Testament.[13][24]: 163, 164 [36][37]: 7–8 Adherents are also referred to as Campbellites by academics[18] and other denominations[38] because it is assumed that they are followers of the teachings of Alexander Campbell, similar to Lutherans or Calvinists. Campbell himself refuted the idea that a denomination was started by him or that he was the head of one in The Christian Baptist publication in 1826 and 1828, stating: "Some religious editors in Kentucky call those who are desirous of seeing the ancient order of things restored, 'the Restorationers', 'the Campbellites'... This may go well with some; but all who fear God and keep his commands will pity and deplore the weakness and folly of those who either think to convince or to persuade by such means" (The Christian Baptist, Vol. IV, 88–89) and: "It is a nickname of reproach invented and adopted by those whose views, feelings and desires are all sectarian – who cannot conceive of Christianity in any other light than an ISM" (The Christian Baptist, Vol. V, 270). He was also associated with the Baptist denomination until 1820. The term "Campbellite" is usually offensive to members of the churches of Christ because members claim no allegiance to anyone except Jesus Christ and teach only what is presented in biblical texts.[39]

Alexander Campbell said the "calling of Bible things by Bible names" was important in the reformation.[40] This became an early slogan of the Restorationist Movement.[41]: 688 These congregations generally avoid names that associate the church with a particular man (other than Christ) or a particular doctrine or theological point of view (e.g., Lutheran, Wesleyan, Reformed).[13][17] They believe that Christ established only one church, and that the use of denominational names serves to foster division among Christians.[24]: 23, 24 [36][42][43][44][45] Thomas Campbell expressed an ideal of unity in his Declaration and Address: "The church of Jesus Christ on earth is essentially, intentionally, and constitutionally one."[41]: 688 This statement essentially echoes the words of Jesus Christ in John 17:21, 23.

Other terms are derived from their use in the New Testament: "church of God", "church of the Lord", "churches of Christ", "church of the first-born", "church of the living God", "the house of God", and "the people of God",[36][46] while terms recognized as scriptural, such as Church of God, are avoided to prevent confusion or identification with other groups that use those designations.[13][36][47] As a practical matter, use of a common term is seen as a way to help individual Christians find congregations with a similar approach to the scriptures.[36][48] Members understand that a scriptural name can be used in a "denominational" or "sectarian" way.[13]: 31 [36]: 83–94, 134–136 [46] Using the term "Church of Christ" exclusively has been criticized as identifying a denomination.[13]: 31 [36]: 83–94, 134–136 [46] Many congregations and individuals do not capitalize the word "church" in the phrases "church of Christ" and "churches of Christ".[49]: 382 [50] This is based on the understanding that the term "church of Christ" is used in the New Testament as a descriptive phrase, indicating that the church belongs to Christ, rather than as a proper name.[36]: 91

Church organization

Congregational autonomy and leadership

Church government is congregational rather than denominational. Churches of Christ purposefully have no central headquarters, councils, or other organizational structure above the local church level.[18]: 214 [21]: 103 [22]: 238 [23]: 124 [51] Rather, the independent congregations are a network with each congregation participating at its own discretion in various means of service and fellowship with other congregations (see Sponsoring church (Churches of Christ)).[14][23]: 124 [52][53] Churches of Christ are linked by their shared commitment to Biblical restoration principles.[14][21]: 106 Congregations which do not participate with other church congregations and which refuse to pool resources in order to support outside causes (such as mission work, orphanages, Bible colleges, etc.) are sometimes called "non-institutional."

Congregations are generally overseen by a plurality of elders who are sometimes assisted in the administration of various works by deacons.[14][23]: 124 [24]: 47, 54–55 Elders are generally seen as responsible for the spiritual welfare of the congregation, while deacons are seen as responsible for the non-spiritual needs of the church.[54]: 531 Deacons serve under the supervision of the elders, and are often assigned to specific ministries.[54]: 531 Successful service as a deacon is often seen as preparation for the eldership.[54]: 531 Elders and deacons are appointed by the congregation based on the qualifications found in 1 Timothy 3 and Titus 1, including that the persons must be male (female elders and deaconesses are not recognized, as these are not found in Scripture).[24]: 53, 48–52 [55][56]: 323, 335 Congregations look for elders who have a mature enough understanding of scripture to enable them to supervise the minister and to teach, as well as to perform "governance" functions.[57]: 298 In the absence of willing men who meet these qualifications, congregations are sometimes overseen by the congregation's men in general.[58]

While the early Restoration Movement had a tradition of itinerant preachers rather than "located Preachers", during the 20th century a long-term, formally trained congregational minister became the norm among Churches of Christ.[54]: 532 Ministers are understood to serve under the oversight of the elders[57]: 298 and may or may not also be qualified as an elder. While the presence of a long-term professional minister has sometimes created "significant de facto ministerial authority" and led to conflict between the minister and the elders, the eldership has remained the "ultimate locus of authority in the congregation".[54]: 531 There is, however, a small segment of Churches of Christ who oppose the "located minister" concept (see below).

Churches of Christ hold to the priesthood of all believers.[59] No special titles are used for preachers or ministers that would identify them as "clergy".[21]: 106 [28]: 112–113 Many ministers have undergraduate or graduate education in religion, or specific training in preaching through a non-college school of preaching.[34]: 215 [54]: 531 [60]: 607 [61]: 672, 673 Churches of Christ emphasize that there is no distinction between "clergy" and "laity" and that every member has a gift and a role to play in accomplishing the work of the church.[62]: 38–40

Variations within Churches of Christ

While there is an identifiable mainstream within the Churches of Christ, there are also significant variations within the fellowship.[18]: 212 [34]: 213 [63]: 31, 32 [64]: 4 [65]: 1, 2 The approach taken to restoring the New Testament church has focused on "methods and procedures" such as church organization, the form of worship, and how the church should function. As a result, most divisions among Churches of Christ have been the result of "methodological" disputes. These are meaningful to members of this movement because of the seriousness with which they take the goal of "restoring the form and structure of the primitive church".[18]: 212

Three-quarters of the congregations and 87% of the membership are described by The Encyclopedia of the Stone–Campbell Movement as "mainstream", sharing a general consensus on practice and theology.[34]: 213

Congregational a cappella music from hymnals (perhaps pitched from a pitch pipe), but directed by any capable song-leader motioning the time signature, is notably characteristic of the Churches of Christ.[22]: 240 [66]: 417 [67] Few congregations clap hands or use musical instruments during "formal" weekly convocations.

The remaining congregations may be grouped into four categories which generally differ from the mainstream consensus in specific practices, rather than in theological perspectives, and tend to have smaller congregations on average.[34]: 213

The largest of these four categories is the "non-institutional" Churches of Christ. This group is notable for opposing congregational support of institutions such as orphanages and Bible colleges. Similarly, non-institutional congregations also oppose the use of church facilities for non-church activities (such as fellowship dinners or recreation); as such, they oppose the construction of "fellowship halls", gymnasiums, and similar structures. In both cases, opposition is based on the belief that support of institutions and non-church activities are not proper functions of the local congregation. Approximately 2,055 congregations fall into this category.[34]: 213 [68]

The remaining three groups, whose congregations are generally considerably smaller than those of the mainstream or non-institutional groups, also oppose institutional support as well as "fellowship halls" and similar structures (for the same reasons as the non-institutional groups), but differ by other beliefs and practices (the groups often overlap, but in all cases hold to more conservative views than even the non-institutional groups):[34]: 213

- One group opposes separate "Sunday School" classes for children or gender-separated (the groups thus meet only as a whole assembly in one area); this group consists of approximately 1,100 congregations. The no Sunday School group generally overlaps with the "one-cup" group and may overlap with the "mutual edification" group as defined below.

- Another group opposes the use of multiple communion cups (the term "one-cup" is often used, sometimes pejoratively as "one-cuppers", to describe this group); there are approximately 550 congregations in this group. Congregations in this group differ as to whether "the wine" should be fermented or unfermented, whether the cup can be refilled if during the service it runs dry (or even if it is accidentally spilled), and whether "the bread" can be broken ahead of time or must be broken by the individual participant during Lord's Supper time.

- The last and smallest group "emphasize[s] mutual edification by various leaders in the churches and oppose[s] one person doing most of the preaching" (the term "mutual edification" is often used to describe this group); there are approximately 130 congregations in this grouping.

Beliefs

Churches of Christ seek to practice the principle of the Bible being the only source to find doctrine (known elsewhere as sola scriptura).[23]: 123 [69] The Bible is generally regarded as inspired and inerrant.[23]: 123 Churches of Christ generally see the Bible as historically accurate and literal, unless scriptural context obviously indicates otherwise. Regarding church practices, worship, and doctrine, there is great liberty from congregation to congregation in interpreting what is biblically permissible, as congregations are not controlled by a denominational hierarchy.[70] Their approach to the Bible is driven by the "assumption that the Bible is sufficiently plain and simple to render its message obvious to any sincere believer".[18]: 212 Related to this is an assumption that the Bible provides an understandable "blueprint" or "constitution" for the church.[18]: 213

If it's not in the Bible, then these folks aren't going to do it.

— Carmen Renee Berry, The Unauthorized Guide to Choosing a Church[22]: 240

Historically, three hermeneutic approaches have been used among Churches of Christ.[27]: 387 [71]

- Analysis of commands, examples, and necessary inferences;

- Dispensational analysis distinguishing between Patriarchal, Mosaic and Christian dispensations (however, Churches of Christ are amillennial and generally hold preterist views); and

- Grammatico-historical analysis.

The relative importance given to each of these three strategies has varied over time and between different contexts.[71] The general impression in the current Churches of Christ is that the group's hermeneutics are entirely based on the command, example, inference approach.[71] In practice, interpretation has been deductive, and heavily influenced by the group's central commitment to ecclesiology and soteriology.[71] Inductive reasoning has been used as well, as when all of the conversion accounts from the book of Acts are collated and analyzed to determine the steps necessary for salvation.[71] One student of the movement summarized the traditional approach this way: "In most of their theologizing, however, my impression is that spokespersons in the Churches of Christ reason from Scripture in a deductive manner, arguing from one premise or hypothesis to another so as to arrive at a conclusion. In this regard the approach is much like that of science which, in practice moves deductively from one hypothesis to another, rather than in a Baconian inductive manner."[71] In recent years, changes in the degree of emphasis placed on ecclesiology and soteriology has spurred a reexamination of the traditional hermeneutics among some associated with the Churches of Christ.[71]

A debate arose during the 1980s over the use of the command, example, necessary inference model for identifying the "essentials" of the New Testament faith. Some argued that it fostered legalism, and advocated instead a hermeneutic based on the character of God, Christ and the Holy Spirit. Traditionalists urged the rejection of this "new hermeneutic".[72] Use of this tripartite formula has declined as congregations have shifted to an increased "focus on 'spiritual' issues like discipleship, servanthood, family and praise".[27]: 388 Relatively greater emphasis has been given to Old Testament studies in congregational Bible classes and at affiliated colleges in recent decades. While it is still not seen as authoritative for Christian worship, church organization, or regulating the Christian's life, some have argued that it is theologically authoritative.[27]: 388

Many scholars associated with the Churches of Christ embrace the methods of modern Biblical criticism but not the associated anti-supernaturalistic views. More generally, the classical grammatico-historical method is prevalent, which provides a basis for some openness to alternative approaches to understanding the scriptures.[27]: 389

Doctrine of salvation (soteriology)

Churches of Christ are strongly anti-Lutheran and anti-Calvinist in their understanding of salvation and generally present conversion as "obedience to the proclaimed facts of the gospel rather than as the result of an emotional, Spirit-initiated conversion".[34]: 215 Churches of Christ hold the view that humans of accountable age are lost because they have committed sins.[23]: 124 These lost souls can be redeemed because Jesus Christ, the Son of God, offered himself as the atoning sacrifice.[23]: 124 Children too young to understand right from wrong and make a conscious choice between the two are believed to be innocent of sin.[21]: 107 [23]: 124 There is no set age for this to occur; it is only when the child learns the difference between right and wrong that they are accountable (James 4:17). Congregations differ in their interpretation of the age of accountability.[21]: 107

Churches of Christ generally teach that the process of salvation involves the following steps:[14]

- One must be properly taught, and hear (Romans 10:14–17);

- One must believe or have faith (Hebrews 11:6, Mark 16:16);

- One must repent, which means turning from one's former lifestyle and choosing God's ways (Acts 17:30);

- One must confess belief that Jesus is the son of God (Acts 8:36–37);

- One must be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ (Acts 2:38); and

- One must live faithfully as a Christian (1 Peter 2:9).

Beginning in the 1960s, many preachers began placing more emphasis on the role of grace in salvation, instead of focusing exclusively on implementing all of the New Testament commands and examples.[64]: 152, 153 This was not an entirely new approach, as others had actively "affirmed a theology of free and unmerited grace", but it did represent a change of emphasis with grace becoming "a theme that would increasingly define this tradition".[64]: 153

Baptism

Baptism has been recognized as the important initiatory rite throughout the history of the Christian Church,[73]: 11 but Christian groups differ over the manner and time in which baptism is administered,[73]: 11 the meaning and significance of baptism,[73]: 11 its role in salvation,[73]: 12 and who is a candidate for baptism.[73]: 12

Baptism in Churches of Christ is performed only by bodily immersion,[21]: 107 [23]: 124 based on the New Testament's use of the Koine Greek verb βαπτίζω (baptizō) which is understood to mean to dip, immerse, submerge or plunge.[14][24]: 313–314 [28]: 45–46 [73]: 139 [74]: 22 Immersion is seen as more closely conforming to the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus than other modes of baptism.[14][24]: 314–316 [73]: 140 Churches of Christ argue that historically immersion was the mode used in the first century, and that pouring and sprinkling emerged later.[73]: 140 Over time these secondary modes came to replace immersion, in the State Churches of Europe.[73]: 140 Only those mentally capable of belief and repentance are baptized (e.g., infant baptism is not practiced).[14][23]: 124 [24]: 318–319 [56]: 195

Churches of Christ have historically had the most conservative position on baptism among the various branches of the Restoration Movement, understanding that repentance and baptism by immersion are necessary parts of conversion.[75]: 61 The most significant disagreements concerned the extent to which a correct understanding of the role of baptism is necessary for its validity.[75]: 61 David Lipscomb argued that if a believer was baptized out of a desire to obey God, the baptism was valid, even if the individual did not fully understand the role baptism plays in salvation.[75]: 61 Austin McGary argued that to be valid, the convert must also understand that baptism is for the forgiveness of sins.[75]: 62 McGary's view became the prevailing one in the early 20th century, but the approach advocated by Lipscomb never totally disappeared.[75]: 62 More recently, the rise of the International Churches of Christ, who "reimmersed some who came into their fellowship, even those previously immersed 'for remission of sins' in a Church of Christ," has caused some to reexamine the question of rebaptism.[75]: 66

Churches of Christ consistently teach that in baptism a believer surrenders his life in faith and obedience to God, and that God "by the merits of Christ's blood, cleanses one from sin and truly changes the state of the person from an alien to a citizen of God's kingdom. Baptism is not a human work; it is the place where God does the work that only God can do."[75]: 66 The term "alien" is used in reference to sinners as in Eph 2:12. Members consider baptism a passive act of faith rather than a meritorious work; it "is a confession that a person has nothing to offer God".[76]: 112 While Churches of Christ do not describe baptism as a "sacrament", their view of it can legitimately be described as "sacramental".[74]: 186 [75]: 66 They see the power of baptism coming from God, who uses baptism as a vehicle, rather than from the water or the act itself,[74]: 186 and understand baptism to be an integral part of the conversion process, rather than as only a symbol of conversion.[74]: 184 A recent trend is to emphasize the transformational aspect of baptism: instead of describing it as nothing more than a legal requirement or sign of something that happened in the past, it is seen as "the event that places the believer 'into Christ' where God does the ongoing work of transformation".[75]: 66 There is a minority that downplays the importance of baptism in order to avoid sectarianism, but the broader trend is to "reexamine the richness of the Biblical teaching of baptism and to reinforce its central and essential place in Christianity".[75]: 66

Because of the belief that baptism is a necessary part of salvation, some Baptists hold that the Churches of Christ endorse the doctrine of baptismal regeneration.[77] However members of the Churches of Christ reject this, arguing that since faith and repentance are necessary, and that the cleansing of sins is by the blood of Christ through the grace of God, baptism is not an inherently redeeming ritual.[73]: 133 [77][78]: 630, 631 One author describes the relationship between faith and baptism this way, "Faith is the reason why a person is a child of God; baptism is the time at which one is incorporated into Christ and so becomes a child of God" (italics are in the source).[56]: 170 Baptism is understood as a confessional expression of faith and repentance,[56]: 179–182 rather than a "work" that earns salvation.[56]: 170

A cappella singing

The Churches of Christ generally combine the lack of any historical evidence that the early church used musical instruments in its worship assemblies[13]: 47 [24]: 237–238 [66]: 415 with the New Testament's lack of scriptures authorizing the use of instruments in worship assemblies[14][24]: 244–246 to conclude that instruments should not be used today in corporate worship. Thus, they have typically practiced a cappella music in their worship assemblies.[14][22]: 240 [23]: 124

The tradition of a cappella congregational singing in the Churches of Christ is deep rooted and the rich history of the practice stimulated the creation of many hymns in the early 20th century. Notable Churches of Christ hymn writers have included Albert Brumley ("I'll Fly Away") and Tillit S. Teddlie ("Worthy Art Thou"). More traditional Church of Christ hymns commonly are in the style of gospel hymnody. The hymnal Great Songs of the Church, which was first published in 1921 and has had many subsequent editions, is widely used in Churches of Christ.[79]

Scriptures cited to support the practice of a cappella worship include:

- Matt 26:30: "And when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives."[24]: 236

- Rom 15:9: "Therefore I will praise thee among the Gentiles, and sing to thy name";[24]: 236

- Eph 5:18–19: "... be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with all your heart,"[14][24]: 236

- 1 Cor 14:15: "I will sing with the Spirit, and I will sing with the understanding also."[24]: 236

- Col 3:16: "Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly; in all wisdom teaching and admonishing one another with psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts unto God."[24]: 237

- Heb 2:12: "I will declare thy name unto my brethren, in the midst of the church will I sing praise unto thee."[24]: 237

- Heb 13:15: By him therefore let us offer the sacrifice of praise to God continually, that is, the fruit of our lips giving thanks to his name.

The use of musical instruments in worship was a divisive topic within the Stone–Campbell Movement from its earliest years, when some adherents opposed the practice on traditional grounds, while others may have relied on a cappella simply because they lacked access to musical instruments. Alexander Campbell opposed the use of instruments in worship. As early as 1855, some Restoration Movement churches were using organs or pianos, ultimately leading the Churches of Christ to separate from the groups that condoned instrumental music.[79] However, since the early 2000's, an increasing number of congregations within the Churches of Christ have begun using musical instruments in their worship assemblies. Some of these latter describe themselves as a "Church of Christ (Instrumental)".[22]: 240 [66]: 417 [80][81][82][65]: 667

Other theological tendencies

Many leaders argue that the Churches of Christ only follow the Bible and have no "theology".[83]: 737 Christian theology as classically understood – the systematic development of the classical doctrinal topics – is relatively recent and rare among this movement.[83]: 737 Because Churches of Christ reject all formalized creeds on the basis that they add to or detract from Scripture, they generally reject most conceptual doctrinal positions out of hand.[84] Churches of Christ do tend to elaborate certain "driving motifs".[83]: 737 These are scripture (hermeneutics), the church (ecclesiology) and the "plan of salvation" (soteriology).[83]: 737 The importance of theology, understood as teaching or "doctrine", has been defended on the basis that an understanding of doctrine is necessary to respond intelligently to questions from others, to promote spiritual health, and to draw the believer closer to God.[76]: 10–11

Churches of Christ avoid the term "theology", preferring instead the term "doctrine": theology is what humans say about the Bible; doctrine is simply what the Bible says.

— Encyclopedia of Religion in the South[18]: 213

Eschatology

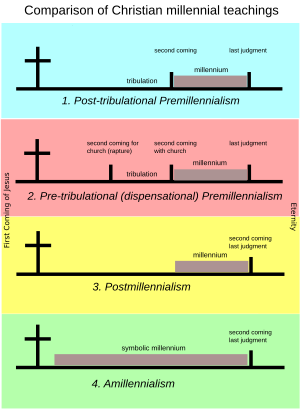

Regarding eschatology (a branch of theology concerned with the final events in the history of the world or of humankind), Churches of Christ are generally amillennial, their originally prevalent postmillennialism (evident in Alexander Campbell's Millennial Harbinger) having dissipated around the era of the First World War. Before then, many leaders were "moderate historical premillennialists" who did not advocate specific historical interpretations. Churches of Christ have moved away from premillennialism as dispensational millennialism has come more to fore in Protestant evangelical circles.[34]: 219 [85] Amillennialism and postmillennialism are the prevailing views today.[23]: 125

Premillennialism was a focus of controversy during the first half of the 20th century.[34]: 219 One of the most influential advocates for that point of view was Robert Henry Boll,[86]: 96–97 [87]: 306 whose eschatological views came to be most singularly opposed by Foy E. Wallace Jr.[88] By the end of the 20th century, however, the divisions caused by the debate over premillennialism were diminishing, and in the 2000 edition of the directory Churches of Christ in the United States, published by Mac Lynn, congregations holding premillennial views were no longer listed separately.[86]: 97 [89]

Work of the Holy Spirit

During the late 19th century, the prevailing view in the Restoration Movement was that the Holy Spirit currently acts only through the influence of inspired scripture.[90] This rationalist view was associated with Alexander Campbell, who was "greatly affected by what he viewed as the excesses of the emotional camp meetings and revivals of his day".[90] He believed that the Spirit draws people towards salvation but understood the Spirit to do this "in the same way any person moves another—by persuasion with words and ideas". This view came to prevail over that of Barton W. Stone, who believed the Spirit had a more direct role in the life of the Christian.[90] Since the early 20th century, many, but not all, among the Churches of Christ have moved away from this "word-only" theory of the operation of the Holy Spirit.[91] As one scholar of the movement puts it, "[f]or better or worse, those who champion the so-called word-only theory no longer have a hold on the minds of the constituency of Churches of Christ. Though relatively few have adopted outright charismatic and third wave views and remained in the body, apparently the spiritual waves have begun to erode that rational rock."[90] The Churches of Christ hold a cessationist perspective on the gifts of the Spirit.[citation needed][92]

The Trinity

Alexander Campbell and Barton W. Stone are recognized as two of the major Reformers of the so-called "Stone–Campbell Movement." Barton Stone was staunchly non-trinitarian as he elucidates in his, "An Address to the Christian Churches in Kentucky, Tennessee, & Ohio On Several Important Doctrines of Religion[93]." Alexander Campbell, "rejected the term 'Trinity,' but Campbell did not reject the theological idea of the tri-unity of the Christian God."[94] The fact that these two movements merged into one shows that this was not a major point of contention, even if it was a point of disagreement.[95]

Church history

The fundamental idea of "restoration" or "Christian Primitivism" is that problems or deficiencies in the church can be corrected by using the primitive church as a "normative model."[96]: 635 The call for restoration is often justified on the basis of a "falling away" that corrupted the original purity of the church.[37][97][98] This falling away is identified with the development of Catholicism and denominationalism.[24]: 56–66, 103–138 [37]: 54–73 [97][98] New Testament verses that discuss future apostasy (2 Thessalonians 2:3) and heresy (e.g., Acts 20:29, 1 Timothy 4:1, 2 Tim 4:1–4:4) are understood to predict this falling away.[97] The logic of "restoration" could imply that the "true" church completely disappeared and thus lead towards exclusivism.[98] Another view of restoration is that the "true Church ... has always existed by grace and not by human engineering" (italics in the original).[99]: 640 In this view the goal is to "help Christians realize the ideal of the church in the New Testament – to restore the church as conceived in the mind of Christ" (italics in the original).[99]: 640 Early Restoration Movement leaders did not believe that the church had ceased to exist, but instead sought to reform and reunite the church.[98][99]: 638 [100][101] A number of congregations' web sites explicitly state that the true church never disappeared.[102] The belief in a general falling away is not seen as inconsistent with the idea that a faithful remnant of the church never entirely disappeared.[24]: 153 [37]: 5 [103]: 41 Some have attempted to trace this remnant through the intervening centuries between the New Testament and the beginning of the Restoration Movement in the early 1800s.[104][105]

One effect of the emphasis placed on the New Testament church is a "sense of historylessness" that sees the intervening history between the 1st century and the modern church as "irrelevant or even abhorrent."[15]: 152 Authors within the brotherhood have recently argued that a greater attention to history can help guide the church through modern-day challenges.[15]: 151–157 [106]: 60–64

Contemporary social and political views

The churches of Christ maintain a significant proportion of political diversity.[107] According to the Pew Research Center in 2016, 50% of adherents of the churches of Christ identify as Republican or lean Republican, 39% identify as Democratic or lean Democratic and 11% have no preference.[108] Despite this, the Christian Chronicle says that the vast majority of adherents maintain a conservative view on modern social issues. This is evident when the Research Center questioned adherents' political ideology. In the survey, 51% identified as "conservative", 29% identified as "moderate" and just 12% identified as "liberal", with 8% not knowing.[109] In contemporary society, the vast majority of adherents of the churches of Christ view homosexuality as a sin.[110] They cite Leviticus 18:22 and Romans 1:26–27 for their position. Most don't view same-sex attraction as a sin; however, they condemn "acting on same-sex desires".[111]

History

Early Restoration Movement history

The Restoration Movement originated with the convergence of several independent efforts to go back to apostolic Christianity.[15]: 101 [36]: 27 Two were of particular importance to the development of the movement.[15]: 101–106 [36]: 27 The first, led by Barton W. Stone, began at Cane Ridge, Kentucky and called themselves simply "Christians". The second began in western Pennsylvania and was led by Thomas Campbell and his son, Alexander Campbell; they used the name "Disciples of Christ". Both groups sought to restore the whole Christian church on the pattern set forth in the New Testament, and both believed that creeds kept Christianity divided.[15]: 101–106 [36]: 27–32

The Campbell movement was characterized by a "systematic and rational reconstruction" of the early church, in contrast to the Stone movement which was characterized by radical freedom and lack of dogma.[15]: 106–108 Despite their differences, the two movements agreed on several critical issues.[15]: 108 Both saw restoring the early church as a route to Christian freedom, and both believed that unity among Christians could be achieved by using apostolic Christianity as a model.[15]: 108 The commitment of both movements to restoring the early church and to uniting Christians was enough to motivate a union between many in the two movements.[64]: 8, 9 While emphasizing that the Bible is the only source to seek doctrine, an acceptance of Christians with diverse opinions was the norm in the quest for truth. "In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, love" was an oft-quoted slogan of the period.[112] The Stone and Campbell movements merged in 1832.[36]: 28 [113]: 212 [114]: xxi [115]: xxxvii

The Restoration Movement began during, and was greatly influenced by, the Second Great Awakening.[116]: 368 While the Campbells resisted what they saw as the spiritual manipulation of the camp meetings, the Southern phase of the Awakening "was an important matrix of Barton Stone's reform movement" and shaped the evangelistic techniques used by both Stone and the Campbells.[116]: 368

Christian Churches and Churches of Christ separation

In 1906, the U.S. Religious Census listed the Christian Churches and the Churches of Christ as separate and distinct groups for the first time.[117]: 251 This was the recognition of a division that had been growing for years under the influence of conservatives such as Daniel Sommer, with reports of the division having been published as early as 1883.[117]: 252 The most visible distinction between the two groups was the rejection of musical instruments in the Churches of Christ. The controversy over musical instruments began in 1860 with the introduction of organs in some churches. More basic were differences in the underlying approach to Biblical interpretation. For the Churches of Christ, any practices not present in accounts of New Testament worship were not permissible in the church, and they could find no New Testament documentation of the use of instrumental music in worship. For the Christian Churches, any practices not expressly forbidden could be considered.[117]: 242–247 Another specific source of controversy was the role of missionary societies, the first of which was the American Christian Missionary Society, formed in October 1849.[118][119] While there was no disagreement over the need for evangelism, many believed that missionary societies were not authorized by scripture and would compromise the autonomy of local congregations.[118] This disagreement became another important factor leading to the separation of the Churches of Christ from the Christian Church.[118] Cultural factors arising from the American Civil War also contributed to the division.[120]

Nothing in life has given me more pain in heart than the separation from those I have heretofore worked with and loved

— David Lipscomb, 1899[121]

In 1968, at the International Convention of Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ), those Christian Churches that favored a denominational structure, wished to be more ecumenical, and also accepted more of the modern liberal theology of various denominations, adopted a new "provisional design" for their work together, becoming the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[49]: 495 Those congregations that chose not to be associated with the new denominational organization continued as undenominational Christian churches and churches of Christ, completing a separation that had begun decades before.[49]: 407–409 The instrumental Christian Churches and Churches of Christ in some cases have both organizational and hermeneutical differences with the Churches of Christ.[18]: 186 For example, they have a loosely organized convention and view scriptural silence on an issue more permissively,[18]: 186 but they are more closely related to the Churches of Christ in their theology and ecclesiology than they are with the Disciples of Christ denomination.[18]: 186 Some see divisions in the movement as the result of the tension between the goals of restoration and ecumenism, with the a cappella Churches of Christ and Christian churches and churches of Christ resolving the tension by stressing Bible authority, while the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) resolved the tension by stressing ecumenism.[18]: 210 [49]: 383

Race relations

Early Restoration Movement leaders varied in their views of slavery, reflecting the range of positions common in the Pre-Civil-War U.S.[122]: 619 Barton W. Stone was a strong opponent of slavery, arguing that there was no Biblical justification for the form of slavery then being practiced in the United States and calling for immediate emancipation.[122]: 619 Alexander Campbell represented a more "Jeffersonian" opposition to slavery, writing of it as more of a political problem than as a religious or moral one.[122]: 619 Having seen Methodists and Baptists divide over the issue of slavery, Campbell argued that scripture regulated slavery rather than prohibited it, and that abolition should not be allowed to become an issue over which Christians would break fellowship with each other.[122]: 619 Like the country as a whole, the assumption of white racial superiority was almost universal among those on all sides of the issue, and it was common for congregations to have separate seating for black members.[122]: 619

After the Civil War, black Christians who had been worshiping in mixed-race Restoration Movement congregations formed their own congregations.[122]: 619 White members of Restoration Movement congregations shared many of the racial prejudices of the times.[122]: 620 Among the Churches of Christ, Marshall Keeble became a prominent African-American evangelist. He estimated that by January 1919 he had "traveled 23,052 miles, preached 1,161 sermons, and baptized 457 converts".[122]: 620

To object to any child of God participating in the service on account of his race, social or civil state, his color or race, is to object to Jesus Christ and to cast him from our association. It is a fearful thing to do. I have never attended a church that negroes did not attend.

— David Lipscomb, 1907[123]

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s the Churches of Christ struggled with changing racial attitudes.[122]: 621 Some leaders, such as Foy E. Wallace Jr., and George S. Benson of Harding University railed against racial integration, saying that racial segregation was the Divine Order.[124][125] Schools and colleges associated with the movement were at the center of the debate.[122]: 621 N.B. Hardeman, the president of Freed-Hardeman, was adamant that the black and white races should not mingle, and refused to shake hands with black Christians.[125] Abilene Christian College first admitted black undergraduate students in 1962 (graduate students had been admitted in 1961).[122]: 621 Desegregation of other campuses followed.[122]: 621 [126]

Efforts to address racism continued through the following decades.[122]: 622 A national meeting of prominent leaders from the Churches of Christ was held in June 1968.[122]: 622 Thirty-two participants signed a set of proposals intended to address discrimination in local congregations, church affiliated activities and the lives of individual Christians.[122]: 622 An important symbolic step was taken in 1999 when the president of Abilene Christian University "confessed the sin of racism in the school's past segregationist policies" and asked black Christians for forgiveness during a lectureship at Southwestern Christian College, a historically black school affiliated with the Churches of Christ.[122]: 622 [127]: 695

Institutional controversy

After World War II, Churches of Christ began sending ministers and humanitarian relief to war-torn Europe and Asia.

Though there was agreement that separate para-church "missionary societies" could not be established (on the belief that such work could only be performed through local congregations), a doctrinal conflict ensued about how this work was to be done. Eventually, the funding and control of outreach programs in the United States such as homes for orphans, nursing homes, mission work, setting up new congregations, Bible colleges or seminaries, and large-scale radio and television programs became part of the controversy.

Congregations which supported and participated in pooling funds for these institutional activities are said to be "sponsoring church" congregations. Congregations which have traditionally opposed these organized sponsorship activities are said to be "non-institutional" congregations. The institutional controversy resulted in the largest division among Churches of Christ in the 20th century.[128]

Separation of the International Churches of Christ

The International Churches of Christ had their roots in a "discipling" movement that arose among the mainline Churches of Christ during the 1970s.[129]: 418 This discipling movement developed in the campus ministry of Chuck Lucas.[129]: 418

In 1967, Chuck Lucas was minister of the 14th Street Church of Christ in Gainesville, Florida (later renamed the Crossroads Church of Christ). That year he started a new project known as Campus Advance (based on principles borrowed from the Campus Crusade and the Shepherding Movement). Centered on the University of Florida, the program called for a strong evangelical outreach and an intimate religious atmosphere in the form of soul talks and prayer partners. Soul talks were held in student residences and involved prayer and sharing overseen by a leader who delegated authority over group members. Prayer partners referred to the practice of pairing a new Christian with an older guide for personal assistance and direction. Both procedures led to "in-depth involvement of each member in one another's lives", and critics accused Lucas of fostering cultism.[130]

The Crossroads Movement later spread into some other Churches of Christ. One of Lucas' converts, Kip McKean, moved to the Boston area in 1979 and began working with "would-be disciples" in the Lexington Church of Christ.[129]: 418 He asked them to "redefine their commitment to Christ," and introduced the use of discipling partners. The congregation grew rapidly, and was renamed the Boston Church of Christ.[129]: 418 In the early 1980s, the focus of the movement moved to Boston, Massachusetts where Kip McKean and the Boston Church of Christ became prominently associated with the trend.[129]: 418 [130]: 133, 134 With the national leadership located in Boston, during the 1980s it commonly became known as the "Boston movement".[129]: 418 [130]: 133, 134 A formal break was made from the mainline Churches of Christ in 1993 with the organization of the International Churches of Christ.[129]: 418 This new designation formalized a division that was already in existence between those involved with the Crossroads/Boston Movement and "mainline" Churches of Christ.[49]: 442 [129]: 418, 419 Other names that have been used for this movement include the "Crossroads movement," "Multiplying Ministries," the "Discipling Movement" and the "Boston Church of Christ".[130]: 133

Kip McKean resigned as the "World Mission Evangelist" in November 2002.[129]: 419 Some ICoC leaders began "tentative efforts" at reconciliation with the Churches of Christ during the Abilene Christian University Lectureship in February 2004.[129]: 419

Restoration Movement timeline

Churches of Christ outside the United States

Most members of the Churches of Christ live outside the United States. Although there is no reliable counting system, it is anecdotally believed there may be more than 1,000,000 members of the Churches of Christ in Africa, approximately 1,000,000 in India, and 50,000 in Central and South America. Total worldwide membership is over 3,000,000, with approximately 1,000,000 in the U.S.[34]: 212

Africa

Although there is no reliable counting system, it is anecdotally believed to be 1,000,000 or more members of the Churches of Christ in Africa.[34]: 212 The total number of congregations is approximately 14,000.[131]: 7 The most significant concentrations are in Nigeria, Malawi, Ghana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, South Africa, South Sudan and Kenya.[131]: 7

Asia

Estimates are that there are 2,000 or more Restoration Movement congregations in India,[132]: 37, 38 with a membership of approximately 1,000,000.[34]: 212 More than 100 congregations exist in the Philippines.[132]: 38 Growth in other Asian countries has been smaller but is still significant.[132]: 38

Australia

Historically, Restoration Movement groups from Great Britain were more influential than those from the United States in the early development of the movement in Australia. Churches of Christ grew up independently in several locations.[133]: 47 While early Churches of Christ in Australia saw creeds as divisive, towards the end of the 19th century they began viewing "summary statements of belief" as useful in tutoring second generation members and converts from other religious groups.[133]: 50 The period from 1875 through 1910 also saw debates over the use of musical instruments in worship, Christian Endeavor Societies and Sunday Schools. Ultimately, all three found general acceptance in the movement.[133]: 51 Currently, the Restoration Movement is not as divided in Australia as it is in the United States.[133]: 53 There have been strong ties with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), but many conservative ministers and congregations associate with the Christian churches and churches of Christ instead.[133]: 53 Others have sought support from non-instrumental Churches of Christ, particularly those who felt that "conference" congregations had "departed from the restoration ideal".[133]: 53

Canada

A relatively small proportion of total membership comes from Canada. A growing portion of the Canadian demographic is made up of immigrant members of the church. This is partly the result of Canadian demographics as a whole, and partly due to decreased interest amongst late generation Canadians.[134] The largest concentration of active congregations in Canada are in Southern Ontario, with notable congregations gathering in Beamsville, Bramalea, Niagara Falls, Vineland, Toronto (several), and Waterloo. However, many congregations of various sizes (typically under 300 members) meet all across Canada.[135]

Great Britain

In the early 1800s, Scottish Baptists were influenced by the writings of Alexander Campbell in the Christian Baptist and Millennial Harbinger.[136] A group in Nottingham withdrew from the Scotch Baptist church in 1836 to form a Church of Christ.[136]: 369 James Wallis, a member of that group, founded a magazine named The British Millennial Harbinger in 1837.[136]: 369 In 1842 the first Cooperative Meeting of Churches of Christ in Great Britain was held in Edinburgh.[136]: 369 Approximately 50 congregations were involved, representing a membership of 1,600.[136]: 369 The name "Churches of Christ" was formally adopted at an annual meeting in 1870.[136]: 369 Alexander Campbell influenced the British Restoration Movement indirectly through his writings; he visited Britain for several months in 1847, and "presided at the Second Cooperative Meeting of the British Churches at Chester".[136]: 369 At that time the movement had grown to encompass 80 congregations with a total membership of 2,300.[136]: 369 Annual meetings were held after 1847.[136]: 369

The use of instrumental music in worship was not a source of division among the Churches of Christ in Great Britain before World War I. More significant was the issue of pacifism; a national conference was established in 1916 for congregations that opposed the war.[136]: 371 A conference for "Old Paths" congregations was first held in 1924.[136]: 371 The issues involved included concern that the Christian Association was compromising traditional principles in seeking ecumenical ties with other organizations and a sense that it had abandoned Scripture as "an all-sufficient rule of faith and practice".[136]: 371 Two "Old Paths" congregations withdrew from the Association in 1931; an additional two withdrew in 1934, and nineteen more withdrew between 1943 and 1947.[136]: 371

Membership declined rapidly during and after the First World War.[136]: 372 [137]: 312 The Association of Churches of Christ in Britain disbanded in 1980.[136]: 372 [137]: 312 Most Association congregations (approximately 40) united with the United Reformed Church in 1981.[136]: 372 [137]: 312 In the same year, twenty-four other congregations formed a Fellowship of Churches of Christ.[136]: 372 The Fellowship developed ties with the Christian churches and churches of Christ during the 1980s.[136]: 372 [137]: 312

The Fellowship of Churches of Christ and some Australian and New Zealand Churches advocate a "missional" emphasis with an ideal of "Five Fold Leadership". Many people in more traditional Churches of Christ see these groups as having more in common with Pentecostal churches. The main publishing organs of traditional Churches of Christ in Britain are The Christian Worker magazine and the Scripture Standard magazine. A history of the Association of Churches of Christ, Let Sects and Parties Fall, was written by David M Thompson.[138] Further information can be found in the Historical Survey of Churches of Christ in the British Isles, edited by Joe Nisbet.[139]

South America

In Brazil there are above 600 congregations and 100,000 members from the Restoration Movement. Most of them were established by Lloyd David Sanders.[140]

See also

- Christian churches and churches of Christ

- Christianity in the United States

- Christian primitivism

- Churches of Christ (non-institutional)

- Congregationalist polity

- Gospel Broadcasting Network (GBN) – a television network affiliated with the Churches of Christ

- House to House Heart to Heart – a printed outreach affiliated with the Churches of Christ

- List of universities and colleges affiliated with the Churches of Christ

- Regulative principle of worship

- Sponsoring church (Churches of Christ)

- World Convention of Churches of Christ

- World Mission Workshop – an annual gathering of students of missions, missionaries, and professors of missions associated with Churches of Christ

Categories

References

Citations

- ^ "Churches of Christ (1906 - Present) - Religious Group". www.thearda.com. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ "Though some in the Movement have been reluctant to label themselves Protestants, the Stone-Campbell Movement is in the direct lineage of the Protestant Reformation. Especially shaped by Reformed theology through its Presbyterian roots, the Movement also shares historical and theological traits with Anglican and Anabaptist forebears." Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, "Protestant Reformation", in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8.

- ^ "Church numbers listed by country". ChurchZip. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2014. This is a country-by-country tabulation, based on the enumeration of specific individual church locations and leaders. While it is known to under-represent certain developing countries, it is the largest such enumeration, and improves significantly on earlier broad-based estimates having no supporting detail.

- ^ "How Many churches of Christ Are There?". The churches of Christ. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Royster, Carl H. (June 2020). "Churches of Christ in the United States" (PDF). 21st Century Christian. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Christian Courier. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "About World Video Bible School". WBVS. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "About The Christian Chronicle". The Christian Chronicle. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "What We Believe". Apologetics Press. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Dave (December 31, 2002). "Who Are These People". Apologetics Press. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "Reaching the Lost" (PDF). House to House. Jacksonville church of Christ. July 2019. p. 2. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

under the oversight of the elders

- ^ Hughes, Richard Thomas (2001). The Churches of Christ. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-275-97074-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rubel Shelly, I Just Want to Be a Christian, 20th Century Christian, Nashville, Tennessee 1984, ISBN 0-89098-021-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Baxter, Batsell Barrett. "Who are the churches of Christ and what do they believe in?". Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Also available via these links to church-of-christ.org Archived 2014-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, cris.com/~mmcoc (archived June 22, 2006) and scriptureessay.com (archived July 13, 2006).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j C. Leonard Allen and Richard T. Hughes, "Discovering Our Roots: The Ancestry of the Churches of Christ," Abilene Christian University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-89112-006-8.

- ^ Howard, V. E. (1971). What Is the Church of Christ? (4th (revised) ed.). Central Printers & Publishers. p. 29. ASIN B001EM1NHM.

The church of Jesus Christ is non-denominational. It is neither Catholic, Jewish nor Protestant. It was not founded in 'protest' of any institution, and it is not the product of the 'Restoration' or 'Reformation.' It is the product of the seed of the kingdom (Luke 8:11ff) grown in the hearts of men.

- ^ a b Batsell Barrett Baxter and Carroll Ellis, Neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jew, Church of Christ (1960) ASIN: B00073CQPM. According to Richard Thomas Hughes in Reviving the Ancient Faith: The Story of Churches of Christ in America, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996, ISBN 0-8028-4086-8, ISBN 978-0-8028-4086-8, this is "arguably the most widely distributed tract ever published by the churches of Christ or anyone associated with that tradition."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Samuel S. Hill, Charles H. Lippy, Charles Reagan Wilson, Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, Mercer University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-86554-758-0, ISBN 978-0-86554-758-2.

- ^ "On the cornerstone of the Southside Church of Christ in Springfield, Missouri, is this inscription: 'Church of Christ, Founded in Jerusalem, A.D. 33. This building erected in 1953.' This is not an unusual claim; for similar wording can be found on buildings of churches of Christ in many parts of the United States. The Christians who use such cornerstones reason that the church of Jesus Christ began on Pentecost, A.D. 33. Therefore, to be true to the New Testament, the twentieth-century church must trace its origins to the first century." Robert W. Hooper, A Distinct People: A History of the Churches of Christ in the 20th Century, p. 1, Simon and Schuster, 1993, ISBN 1-878990-26-8, ISBN 978-1-878990-26-6.

- ^ "Traditional Churches of Christ have pursued the restorationist vision with extraordinary zeal. Indeed, the cornerstones of many Church of Christ buildings read 'Founded, A.D. 33.' " Jill, et al. (2005), "Encyclopedia of Religion", p. 212.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Stuart M. Matlins, Arthur J. Magida, J. Magida, How to Be a Perfect Stranger: A Guide to Etiquette in Other People's Religious Ceremonies, Wood Lake Publishing Inc., 1999, ISBN 1-896836-28-3, ISBN 978-1-896836-28-7, Chapter 6 – Churches of Christ.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Ron Rhodes, The Complete Guide to Christian Denominations, Harvest House Publishers, 2005, ISBN 0-7369-1289-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r V. E. Howard, What Is the Church of Christ? 4th Edition (Revised) Central Printers & Publishers, West Monroe, Louisiana, 1971.

- ^ Goldberg, Jonah. Eschatological Weeds. The Remnant. Retrieved June 6, 2020 – via Apple Podcasts.

- ^ Col. 2:14.

- ^ a b c d e Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, entry on Hermeneutics.

- ^ a b c Edward C. Wharton, The Church of Christ: The Distinctive Nature of the New Testament Church, Gospel Advocate Co., 1997, ISBN 0-89225-464-5.

- ^ David Pharr, The Beginning of Our Confidence: Seven Weeks of Daily Lessons for New Christians, 21st Century Christian, 2000, ISBN 0-89098-374-7.

- ^ "Churches of Christ - 10 Things to Know about their History and Beliefs". November 1, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Church numbers listed by country". ChurchZip. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2022. This is a country-by-country tabulation, based on the enumeration of specific individual church locations and leaders. While it is known to under-represent certain developing countries, it is the largest such enumeration, and improves significantly on earlier broad-based estimates having no supporting detail.

- ^ a b Barry A. Kosmin and Ariela Keysar, American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS 2008) Archived April 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Trinity College, March 2009.

- ^ "The Religious Composition of the United States," U.S. Religious Landscape Survey: Chapter 1, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, Pew Research Center, February 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, "Churches of Christ", in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8.

- ^ a b Flavil Yeakley, Good News and Bad News: A Realistic Assessment of Churches of Christ in the United States: 2008; an mp3 of the author presenting some of the results at the 2009 East Tennessee School of Preaching and Ministry lectureship on March 4, 2009, is available here[permanent dead link] and a PowerPoint presentation from the 2008 CMU conference using some of the survey results posted on the Campus Ministry United website is available here.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Monroe E. Hawley, Redigging the Wells: Seeking Undenominational Christianity, Quality Publications, Abilene, Texas, 1976, ISBN 0-89137-512-0 (paper), ISBN 0-89137-513-9 (cloth)

- ^ a b c d J. W. Shepherd, The Church, the Falling Away, and the Restoration, Gospel Advocate Company, Nashville, Tennessee, 1929 (reprinted in 1973)

- ^ "Campbellism and the Church of Christ" Archived 2015-01-09 at the Wayback Machine Morey 2014.

- ^ The Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary describes the term as "sometimes offensive." Merriam-Webster, I. (2003). Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary. (Eleventh ed.). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc. Entry on "Campbellite."

- ^ Campbell, Alexander. Walters, Joseph A. (ed.). "On the Breaking of Bread". Scroll Publishing. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, "Slogans", in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8,

- ^ Thomas Campbell, Declaration and Address, 1809, available on-line here

- ^ O. E. Shields, "The Church of Christ," The Word and Work, VOL. XXXIX, No. 9, September 1945.

- ^ M. C. Kurfees, "Bible Things by Bible Names – The General and Local Senses of the Term 'Church'", Gospel Advocate (October 14, 1920):1104–1105, as reprinted in Appendix II: Restoration Documents of I Just Want to Be a Christian, Rubel Shelly (1984)

- ^ J. C. McQuiddy, "The New Testament Church", Gospel Advocate (November 11, 1920):1097–1098, as reprinted in Appendix II: Restoration Documents of I Just Want to Be a Christian, Rubel Shelly (1984)

- ^ a b c M. C. Kurfees, "Bible Things by Bible Names – Different Designations of the Church Further Considered", Gospel Advocate (September 30, 1920):958–959, as reprinted in Appendix II: Restoration Documents of I Just Want to Be a Christian, Rubel Shelly (1984)

- ^ Within the Restoration Movement, congregations that do not use musical instruments in worship use the name "Church of Christ" almost exclusively; congregations that do use musical instruments most often use the term "Christian Church." Monroe E. Hawley, Redigging the Wells: Seeking Undenominational Christianity, 1976, page 89.

- ^ As, e.g., for listings in the yellow pages.

- ^ a b c d e Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ Examples of this usage include the Gospel Advocate website Archived February 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine ("Serving the church of Christ since 1855" – accessed October 26, 2008); the Lipscomb University website ("Classes in every area are taught in a faith-informed approach by highly qualified faculty who represent the range of perspectives that exist among churches of Christ." – accessed October 26, 2008); the Freed-Hardeman University website Archived 2008-10-09 at the Wayback Machine ("Freed-Hardeman University is a private institution, associated with churches of Christ, dedicated to moral and spiritual values, academic excellence, and service in a friendly, supportive environment... The university is governed by a self-perpetuating board of trustees who are members of churches of Christ and who hold the institution in trust for its founders, alumni, and supporters." – accessed October 26, 2008); Batsell Barrett Baxter, Who are the churches of Christ and what do they believe in? (Available on-line here Archived 2008-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, here, here Archived 2014-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, here Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine and here Archived 2010-11-30 at the Wayback Machine); Batsell Barrett Baxter and Carroll Ellis, Neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jew, tract, Church of Christ (1960); Monroe E. Hawley, Redigging the Wells: Seeking Undenominational Christianity, Quality Publications, Abilene, Texas, 1976; Rubel Shelly, I Just Want to Be a Christian, 20th Century Christian, Nashville, Tennessee 1984; and V. E. Howard, What Is the Church of Christ? 4th Edition (Revised), 1971; Website of the Frisco church of Christ ("Welcome to the Home page for the Frisco church of Christ in Frisco, Texas." – accessed October 27, 2008); website of the church of Christ Internet Ministries ("The purpose of this Web Site is to unite the churches of Christ in one accord." – accessed October 27, 2008) "The Church of Christ at Woodson Chapel : Welcome!". Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ "Churches of Christ from the beginning have maintained no formal organization structures larger than the local congregations and no official journals or vehicles declaring sanctioned positions. Consensus views do, however, often emerge through the influence of opinion leaders who express themselves in journals, at lectureships, or at area preacher meetings and other gatherings" page 213, Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages

- ^ "Churches of Christ adhere to a strict congregationalism that cooperates in various projects overseen by one congregation or organized as parachurch enterprises, but many congregations hold themselves apart from such cooperative projects." Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, page 206, entry on Church, Doctrine of the

- ^ "It is nothing less than phenomenal that the Churches of Christ get so much done without any centralized planning or structure. Everything is ad hoc. Most programs emerge from the inspiration and commitment of a single congregation or even a single person. Worthwhile projects survive and prosper by the voluntary cooperation of other individuals and congregations." Page 449, Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ a b c d e f Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Ministry

- ^ Everett Ferguson, "Authority and Tenure of Elders", Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Restoration Quarterly, Vol. 18 No. 3 (1975): 142–150

- ^ a b c d e Everett Ferguson, The Church of Christ: A Biblical Ecclesiology for Today, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1996, ISBN 0-8028-4189-9, ISBN 978-0-8028-4189-6, 443 pages

- ^ a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Elders, Eldership

- ^ "Where elderships do not exist, most congregations function through a 'business meeting' system that may include any member of the congregation or, in other cases, the men of the church." Page 531, Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Ministry

- ^ Roberts, Price (1979). Studies for New Converts. Cincinnati: The Standard Publishing Company. pp. 53–56.

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Preaching

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Schools of Preaching

- ^ R. B. Sweet, Now That I'm a Christian, Sweet Publishing, 1948 (revised 2003), ISBN 0-8344-0129-0

- ^ Jeffery S. Stevenson, All People, All Times Rethinking Biblical Authority in Churches of Christ, Xulon Press, 2009, ISBN 1-60791-539-1, ISBN 978-1-60791-539-3

- ^ a b c d Richard Thomas Hughes and R. L. Roberts, The Churches of Christ, 2nd Edition, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 0-313-23312-8, ISBN 978-0-313-23312-8, 345 pages

- ^ a b Ralph K. Hawkins, A Heritage in Crisis: Where We've Been, Where We Are, and Where We're Going in the Churches of Christ, University Press of America, 2008, 147 pages, ISBN 0-7618-4080-X, 9780761840800

- ^ a b c Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Instrumental Music

- ^ Ross, Bobby Jr (January 2007). "Nation's largest Church of Christ adding instrumental service". christianchronicle.org. The Christian Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Ross, Bobby Jr. "Who are we?". Features. The Christian Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 19, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "Whenever there are disagreements in the Churches of Christ, a 'reference to the scriptures is made in settling every religious question. A pronouncement from the scripture is considered the final word.'" page 240, Carmen Renee Berry, The Unauthorized Guide to Choosing a Church, Brazos Press, 2003

- ^ See F. LaGard Smith, "The Cultural Church", 20th Century Christian, 1992, 237 pages, ISBN 978-0-89098-131-3

- ^ a b c d e f g Thomas H. Olbricht, "Hermeneutics in the Churches of Christ," Archived 2008-09-22 at the Wayback Machine Restoration Quarterly, Vol. 37/No. 1 (1995)

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, page 219

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tom J. Nettles, Richard L. Pratt, Jr., John H. Armstrong, Robert Kolb, Understanding Four Views on Baptism, Zondervan, 2007, ISBN 0-310-26267-4, ISBN 978-0-310-26267-1, 222 pages

- ^ a b c d Rees Bryant, Baptism, Why Wait?: Faith's Response in Conversion, College Press, 1999, ISBN 0-89900-858-5, ISBN 978-0-89900-858-5, 224 pages

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Baptism

- ^ a b Harold Hazelip, Gary Holloway, Randall J. Harris, Mark C. Black, Theology Matters: In Honor of Harold Hazelip: Answers for the Church Today, College Press, 1998, ISBN 0-89900-813-5, ISBN 978-0-89900-813-4, 368 pages

- ^ a b Douglas A. Foster, "Churches of Christ and Baptism: An Historical and Theological Overview," Archived May 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Restoration Quarterly, Volume 43/Number 2 (2001)

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Regeneration

- ^ a b Wakefield, John C. (January 31, 2014). "Stone-Campbell tradition, the". The Grove Dictionary of American Music, 2nd edition. Grove Music Online.